Chapter 18

Springfield Is a Vast Hospital

Compared to later Civil War battles, the number of men engaged at Wilson’s Creek and the casualties suffered there were modest. But when the casualty figures (the combination of killed, wounded, and missing) are placed in the perspective of previous American history and viewed as a percentage of the forces engaged, it is clear that Wilson’s Creek was a major, costly battle. The best estimate for McCulloch’s Western Army is 277 dead and 945 wounded, for a casualty rate of 12 percent. The total number of dead and wounded—1,222—was higher than the number suffered by Americans in any single battle of the Mexican War. As a percentage of the force engaged, the Southerners had a higher casualty rate than occurred in all but three of the nine major battles of the Mexican War. Lyon’s Army of the West had an estimated 285 killed, 873 wounded, and 186 missing, for a casualty rate of 24.5 percent. Both in total numbers and as a percentage of the force engaged, Lyon’s losses were greater than those of any battle in the Mexican War.1

Casualties were not distributed equally, of course. On both sides the infantry suffered more heavily than the cavalry or artillery. In the Western Army, losses were twice as high in the Confederate troops and the Missouri State Guard as in the Arkansas State Troops. Among the Missouri units, Rains’s Division had the lowest casualty rate (9.7 percent), Clark’s Division the highest (20 percent). Overall, the units hardest hit were the First Arkansas Mounted Rifles (32.8 percent casualties), Kelly’s Infantry (34.5 percent), and Burbridge’s Infantry (36.2 percent). On the Northern side, losses were particularly severe in the First Missouri Infantry (38 percent), the Second Missouri Infantry (36.6 percent), and the First Kansas Infantry (35.5 percent). Indeed, over the course of the war only six Union regiments had a larger total number of dead and mortally wounded in a single engagement than did the First Kansas, which sacrificed 284 men at Wilson’s Creek.2

The primitive state of medical knowledge in the nineteenth century meant that men wounded during the Civil War had a far greater chance of dying than modern combatants. Yet a statistical analysis of the casualties at Wilson’s Creek does little to convey the suffering of the men who struggled there. Events during the weeks after the battle demonstrate that the tragedy that occurred on August 10 embraced an area far wider than the slopes of Bloody Hill and a much larger population than just those in uniform. For like all battles in the Civil War, Wilson’s Creek was in part a community experience. Its impact on civilians, both on the battlefield itself and in Springfield, was devastating. The response of civilians to news of the battle underscores the continuing close relationship between military units and their home communities.

Few Civil War commanders prepared adequately for their men’s medical needs early in the war. Shortly after his arrival in Springfield, Nathaniel Lyon had ordered Dr. E. C. Franklin to establish a military hospital. Franklin chose the unfinished courthouse building being erected on the town square. Although sometimes styled “Chief Surgeon,” he was in charge of the Springfield hospital only, having previously been attached to the Fifth Missouri. Why Lyon selected Franklin, recently a civilian, over one of the three army doctors who accompanied his Regulars is unknown, but soldiers praised the hospital’s cleanliness and the dedication of the doctors there. Most of Lyon’s units had both surgeons and assistant surgeons attached to them, but there was no medical director for the Army of the West and no coordination among the fifteen doctors present, at least two of whom were described as incompetent by their peers. Medical supplies considered adequate by the standards of the day reached Springfield, but these were not distributed equally, and in the volunteer regiments the doctors relied on the instruments from their civilian practice, as the army had nothing to give them.3

Lyon’s concern had been for illnesses, not battle casualties. When the Federals marched to the fray on August 9, each unit was left to look after its own wounded. Once the Federals became heavily engaged on Bloody Hill, surgeons began treating the wounded immediately behind the lines. For example, Dr. W. H. White of the First Iowa had the patients brought to him laid out in a triangle and moved back and forth among the three divisions to treat them. Eventually Major John Schofield of Lyon’s staff saw that a central field hospital was set up in a ravine. This was probably the one that opened toward Gibson’s Mill, although a few sources suggest that it was another one just north of Bloody Hill. No field hospital was established for the men who accompanied Colonel Franz Sigel, as they changed position frequently. Indeed, although he took along a wagon containing a quantity of medical supplies and litters for removing the wounded, these were never unpacked. As better facilities existed in Springfield, the Federal doctors did not attempt major surgery in the field. According to one report, no amputations were performed. Dr. H. M. Sprague of the Regulars admitted, “The attention shown the wounded was good, but not specially praiseworthy.”4

The Southern forces were surprised in their camps and remained in possession of the ground. This gave them an advantage in treating their own men but left them with the burden of caring for the enemy’s wounded following the Federal retreat. There were at least twenty-four surgeons assigned to the Missouri State Guard units in the field. Records are incomplete and the actual number of doctors present was probably higher. All five divisions had chief surgeons, at least three of whom were appointed prior to the battle, but coordination was absent. A soldier in Clark’s Division complained that the State Guard had “no organized hospital corps, no stretchers on which to bear off the wounded.”5 Little is known about the medical personnel in the Arkansas State Troops or the Confederate units under Ben McCulloch’s direct command. Nothing suggests that an effort was made above the regimental level to prepare for the inevitable consequences of battle.

The plight of the Union wounded was arguably worse than that of their foe. Fearing that the rumble of wheeled vehicles might betray his surprise march, Lyon initially ordered all ambulances to be left in Springfield. After Sturgis pleaded with him, he reluctantly allowed two ambulances to accompany the main column, but none went with Sigel. The ambulances apparently did not attempt to make round-trips to Springfield during the battle but remained until Sturgis ordered the retreat. And burdened far beyond their intended capacity, they could not have transported more than two or three dozen of the hundreds of Federal wounded from the field. Once the order to withdraw was given, wheeled vehicles of every description were confiscated from nearby farms and pressed into service. There were few in number, as almost all of the severely wounded Federal soldiers remained on the battlefield. Those with lesser injuries, the so-called walking wounded, scrambled for safety with no help from officialdom. To modern analysts such conditions are tantamount to criminal neglect, but they were hardly unusual in the initial phases of the Civil War.6

While community spirit helped sustain the common soldiers in battle, that same corporate sense of honor ironically weakened the armies somewhat because of the failure to prepare adequately for casualties. The men in the ranks stood literally side by side with neighbors from home, and when men fell wounded their comrades dropped out of the battle to care for them. In a newspaper letter, Joseph Martin of Atchison’s All Hazard company related without apology how he left the fight to look after his friend George Keith. “I found him, took charge of him and carried him to one of the hospital wagons, dressed his wounds and placed him in a wagon to be carried to town,” Martin wrote. “Many of the wagons were heaping full, every man was trying to get friends into them, but I succeeded. . . . He depended upon me to take care of him, which I did.” Similarly, when Hugh J. Campbell of the Muscatine Grays captured some horses abandoned near Gibson’s Mill, he gave them only to wounded fellow Iowans. Shot in the foot himself, he nevertheless managed to steal at gunpoint a horse ridden by a Northern officer’s servant, giving it to his wounded friend Newton Brown. Campbell gleefully related this larceny at the expense of “a darkey” to readers of the Muscatine Weekly Journal. Conduct unthinkable at the beginning of the campaign became not only acceptable but also a source of humor once battle was joined.7

Things differed little on the Southern side, where strength was also depleted due to the lack of medical preparations. John D. Bell of Burbridge’s Infantry recalled that when a man was wounded “it took from two to four of his friends to bear him to some shady nook, where he was left with a canteen of water.” Although Bell contended that “in almost every case” these Good Samaritans returned to the fight, his postwar recollections are probably too forgiving. Over 900 men were wounded in the Southern army, and in all likelihood at least another 900 to 1,000 men withdrew from the fight for a significant period to care for comrades. This effectively eroded McCulloch’s combat strength by as much as an additional 10 percent. On the other hand, similar behavior reduced Lyon’s strength in like proportion.8

Several impromptu field hospitals were established along the banks of Wilson Creek, perhaps because the wounded crawled there seeking water and shade. Trees and underbrush grew thick beside the stream, and soldiers instinctively carried their wounded friends to cover. Because the battle took place amid their camps, the Southerners used their various wagons to transport the wounded to safety even during combat. This was done spontaneously, for there was no organized effort to bring in the wounded until after the battle ended, when each regiment detailed men for that purpose. The positions of the battle lines meant that no place was truly safe. Artillery and small arms fire passed constantly above the Southern hospitals, which were occasionally targeted by accident. Shortly after firing commenced Confederate surgeon William A. Cantrell set up a hospital “near the centre of the battlefield.” Amazingly, he escaped injury, but a physician in Slack’s Division and several wounded soldiers, both Northern and Southern, were killed at a creek bank dressing station.9

Cooperation in regard to medical care was one of the few humane notes amid the general carnage, as surgeons attended men without regard to political affiliation. “I have never before witnessed such a heartrendering scene,” wrote Colonel John Hughes of the Missouri State Guard. “State, Federal, and Confederate troops in one red ruin, blent on the field—enemies in life, in death friends, relieving each others’ sufferings.”10 Indeed, before the last firing died away a Federal doctor risked his life to contact McCulloch, opening negotiations concerning the joint treatment of the wounded. Even so, the surgeons were overwhelmed by the task facing them. They worked incredibly long hours, but despite their best efforts suffering of the wounded was prolonged and terrible. The Federals began moving their injured to Springfield during the afternoon and evening of August 10, and the Southerners began doing the same the following day. Nevertheless, on August 12 Dr. John Wyatt wrote in his diary that “many of the wounded are lying where they fell in the blazing sun, unable to get water and any kind of aid. Blow flies swarm over the living and the dead alike. I saw men not yet dead [with] their eyes, nose & mouth full of maggots.”11

Presumably men still lay without cover because every house, cabin, barn, or dwelling in the vicinity of the battlefield was already overflowing with wounded. The engagement was obviously an unmitigated disaster for all civilians living nearby, and for many it was probably the most memorable event in their lives. When Mary Johnson died in 1903 at the age of eighty-three, for example, her obituary mentioned that she had tended the wounded at Wilson’s Creek. Living on a substantial farm just east of the Ray family, she was a widow with two children at the time of the fighting, and the disruption in their lives must have been severe. Elias Short and his family returned home to find wounded Union soldiers being transferred from their farm to Springfield. The house had not been looted or despoiled, although “the bed clothing had been torn into strips to be used in binding up the wounds of the Union men.”12

Detailed information regarding the impact of the battle on civilians has survived only in relation to the Sharp and Ray families. Before the conflict the Sharp home was already being used as a hospital for members of Greer’s South Kansas-Texas Regiment who had fallen ill. When the fighting erupted, Joseph Sharp, his wife Mary, son Robert, and daughters Margaret and Mary took shelter in the cellar, and the makeshift hospital was evacuated. Artillery projectiles began crashing through the house, devastating the interior. There was extensive damage to the barn and other outbuildings as well. What crops had not been eaten by the encamped Southerners were probably trampled during combat. Fence rails were knocked down, and dead horses from Sigel’s luckless battery lay scattered about.13

Three stories exist concerning the reaction of the Sharps. Writing long after the war, Private Joseph Mudd of the Missouri State Guard recalled that from a distance he saw Mary Sharp vigorously encouraging the Southerners as they drove Sigel from the field. Also writing from memory, Sergeant William Watson of the Third Louisiana described how he broke into the family’s locked house and found the Sharps cowering in the cellar behind a barrel of apples. They did not object when his comrades promptly appropriated the apples, but Mary protested in a shrill voice that the morning’s cannoneering had rendered Joseph deaf. “I felt like saying that, considering her gift of speech, a worse thing might have happened to the old man,” Watson wrote. Mary climbed cautiously from her refuge, “but on seeing the wreck, and looking out and seeing the dead men and horses lying in the front of the house, she broke into a greater fury than ever,” the sergeant noted. “Who was going to pay for all this?” she exclaimed. “Who was going to take away them dead folks and dead horses? Was she to have them lying stinking around her house?” Mary continued in this manner until Watson happily rejoined his regiment. Her comments when dozens of bleeding men with little or no control over their bodily functions were carried into her home can be imagined. Finally, just a few days after the battle Colonel Elkanah Greer, in a letter to a friend in Texas, wrote: “The battle raged hottest around the house of an old gentleman named Sharp, near the centre of the battlefield. After the roar of cannon and the rattle of small arms had ceased for a short time, an old lady came out of the house with a bundle of clothes on her arm, passing over and around the dead Dutch that lay in the yard, and near the fences, to hang out clothes. Placing her spectacles high up on her nose, her right arm akimbo, she exclaimed in a singular and doleful tone, ‘Well dese folks have kicked up a monstrous fuss here to-day.’”14

These accounts demonstrate the difficulty historians face in evaluating evidence. Can the chronicles of Mudd and Watson be reconciled? Does Greer’s letter refer to Mary Sharp or (note the dialect speech) one of the household’s slaves? Regardless of their differences, the stories told about the Sharps remind us that civilians were intimately involved in the battle. The families in the neighborhood of Wilson Creek lost property worth thousands of dollars without receiving a penny in compensation from either the Union or Confederate governments. If not shattered by artillery or musket fire, their homes were damaged when first beds and then every square inch of floor space was covered with the wounded. In some cases, injured soldiers remained there for weeks. Finally, dollar amounts cannot measure the psychological trauma that these residents doubtless suffered. Such things as Mrs. Sharp’s fear for the safety of her teenage daughters can be assumed but not documented.

The misery endured by the Ray family was almost as great as that of the Sharps. John Ray viewed the entire fight from his front porch while the rest of the family remained in the cellar. Shortly after the engagement in Ray’s cornfield ended, the house became a hospital. Although a chicken coop was hit by artillery fire and some other outbuildings were slightly damaged, the family dwelling was not struck. A large yellow hospital flag spared the site from all but accidental fire. But if the buildings were essentially unscathed, the household’s ordeal was severe. For some five hours, Roxanna Ray and eight of her children, their slave Rhoda and her children, and Julius Short, who resided with the Rays, sat in a dark, cramped cellar. When they emerged, wounded men covered the floors and occupied every bed. Unlike Mary Sharp, Roxanna did not waste any time venting her feelings on the unfairness of what had happened. She, Rhoda, and perhaps some of the older children immediately began to assist in caring for the wounded, primarily by hauling water from the nearby springhouse. Some of the wounded, too badly injured to be moved to Springfield, remained in the Ray home for six weeks. John Ray’s activities during the afternoon are unknown, but that evening he was forced to act as a guide for a group of prisoners being escorted to Springfield. Because all of his horses had been stolen, he had to walk. The family was very anxious for his safety, but John may have been more worried about his losses of grain and livestock. Although a Unionist, he was never compensated.15

The battle also had an impact on civilians living beyond its immediate confines. William Gilbert, his wife Elizabeth, and her aunt, whose name is unknown, lived about three miles from Springfield. Scouts and foragers from both the Northern and Southern forces annoyed them so frequently that they finally began sleeping in a cave for safety. Nevertheless, William formed some kind of attachment with the Kansas troops, and when they marched out on August 9 he accompanied them as an unenlisted volunteer. When Elizabeth and her aunt heard the artillery in the distance on August 10, they gathered supplies and headed toward the sound of the guns to treat the wounded. In writing about their experiences over forty years later, Elizabeth still remembered with horror the gaping wounds she had seen on some of the fallen men. The scale of the suffering shocked her, and much of their labor seemed to be in vain. “We raised up the heads of many a wounded soldier and propped them up only to see them die in a few minutes,” she recalled. When the cloth they had brought for bandages ran out, Elizabeth tore up her apron and her aunt her entire skirt. They did not get back to the family farm until two o’clock the next morning.16

A postwar photograph of the home of John Ray (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Although it is impossible to estimate how many women in the neighborhood volunteered their services as nurses, the number was clearly substantial. On August 13 Dr. Wyatt wrote in his diary, “The fair sex, God bless them, are doing all they can in the way of cooking, serving, and nursing for [the] sick and wounded.”17 He may have been referring to women from Springfield as well as locals, for the town was completely caught up in the tragic aftermath of the battle.

Many Springfield citizens fled prior to August 10, heading for Rolla with one of the columns made up of Federal soldiers who were either sick or nearing their date of discharge. According to newspaperman Franc Wilkie, all who remained were awake before dawn on the fateful day, listening for the sounds that would mark the opening of the battle. “About ten minutes past five,” Wilkie wrote, “the heavy boom of artillery rolled through the town like the muttering of a thunder storm upon the horizon, and sent a thrill through every heart, like a shock of electricity.” Although Wilkie soon departed to view the battle firsthand, the townsfolk endured hours of anxiety before learning anything about the conflict’s outcome. By mid-morning they could see smoke rising in the far distance but could not interpret its portent. Shortly after 3:00 P.M. the wounded began streaming in on foot and horseback, bringing news of Lyon’s death. They were followed by ambulances, wagons, carriages, and other wheeled conveyances, all overflowing with men needing attention. The hospital in the courthouse was soon filled, so the Union authorities took over the Bailey House Hotel. When the hotel filled up, the wounded were sent to local churches and schools. But even this was insufficient, and arriving wounded soldiers had to be placed “side by side along the streets.” Finally, private dwellings were requisitioned. According to one account, between thirty and forty citizens’ homes were occupied by the wounded. This represented a substantial portion of the houses in Springfield. Another eyewitness stated that “nearly all the private dwellings” were taken over. A Union physician later recalled how “the women of Springfield, with their hearts full of love and tenderness for the suffering soldiers, came with prepared food, and with gentle hands assisted with every means in their power to soothe the dying soldier and relieve the pain of the suffering.” The doctor could not recall the names of all who helped, but he particularly remembered the generosity of the Boyd, Graves, Jenkins, Logan, Beal, Jameston, Fairchilds, Waddle, Lindenbauer, and Crenshaw families. Their charity was not without cost. The total dollar value of damage to the town as a result of medical treatment was unquestionably large. Only a small amount of compensation was ever received, and that after the war.18

Most Springfield citizens were pro-Union. Once it became clear that the battle was lost and the Federal forces would retreat, many began preparing to evacuate. Left alone after the earlier departure of her husband, Congressman John Phelps, Mary Phelps sent her children and all but one of the family’s seventeen slaves to Rolla in two covered wagons. She and a slave named George, who refused to leave her side, remained to tend the wounded. Some merchants, who had been charging exorbitant prices to the Union troops enduring half rations, now gave away food or dumped it into the streets rather than leave it for the enemy to confiscate. Wilkie wrote that “Springfield was the scene of great confusion—citizens anticipating an instant attack were packing up their effects and flying in crowds to all parts of the state for safety.” When the Southern forces arrived, they noted that relatively few citizens, especially women, remained. Their absence made their property easy pickings for looters, despite the guards McCulloch posted to maintain order. In some cases, Springfieldians in the Missouri State Guard may have been retaliating for damage inflicted on their own homes by the fleeing Unionists. Harris Flanagin, whose company of the Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles was detailed for guard duty, estimated that fewer than twenty women remained in the whole town. “We treat the union men much better than the Missourians do,” he noted.19

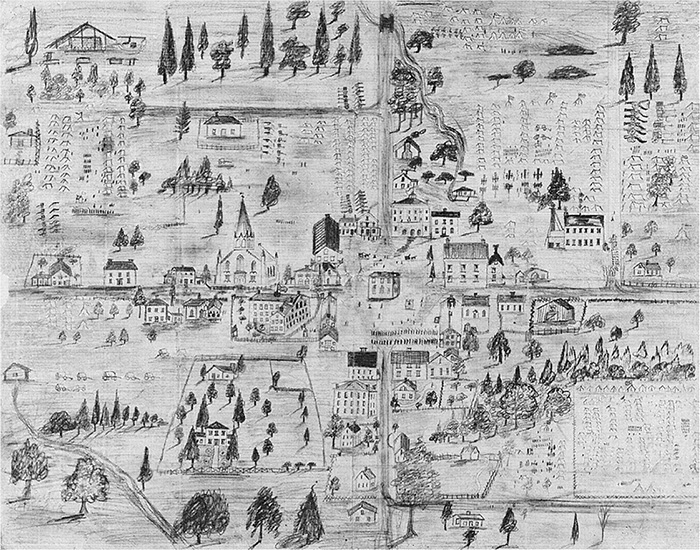

A drawing of Springfield made by Private Andrew Tinkham, Scott’s Guards, First Kansas Infantry, in October or November 1861, showing the camps of the Union forces that reoccupied the town. Published here for the first time. (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

With the state bitterly divided, it was hardly surprising that Sterling Price’s men were particularly elated by the victory. Well-wishers and prospective recruits for the State Guard soon flocked to Springfield. When Dr. Wyatt first visited town to assist in shifting the wounded from the battlefield, he witnessed an important ceremony. “The flag of the Confederacy was raised amidst the wildest enthusiasm by all the people,” he wrote. “Everyone seemed wild with joy except a few sad faced Dutch who had been left behind by their army.”20

Elation soon gave way to more somber emotions amid the lingering evidence of victory’s cost. “Springfield is a vast hospital,” wrote Dr. William Cantrell, surgeon of the First Arkansas Mounted Rifles, to friends in Little Rock. “There is not sufficient medical aid here—a hundred doctors could be employed constantly,” he lamented, estimating that four months would pass before enough soldiers recovered to alleviate the situation. Private John B. Clark, a wounded Kansan forced to stay behind, made an equally discouraging evaluation. “Springfield is the most offensive place you was ever in; the stench from the dead and dying is so offensive as to be almost intolerable in some quarters,” he informed his relatives. Indeed, a Union doctor who remained with his patients recalled that days passed before the surgeons “succeeded in bringing partial order out of utter chaos.” Ben McCulloch and Bart Pearce took pains to visit not only their own hospitalized men but the Union wounded as well, a fact reported favorably in Northern newspapers. But they, like Sterling Price, were too busy with strategy to give medical affairs more than scant attention.21

The physicians did not have to work alone for long. Help arrived rather quickly, as telegraphic communications and newspapers that copied stories from other journals spread news of the battle. The telegraph lines that ran along the Wire Road to link Fayetteville, Arkansas, and Jefferson City, Missouri, were apparently cut both north and south of Springfield, as the earliest news came out of Rolla, where the Army of the West halted its retreat. From there, word of the battle reached St. Louis. Information first published in that city’s various newspapers was soon relayed west to Kansas City and throughout Kansas, north to Davenport and across Iowa, and southeast to Memphis, Tennessee, from whence it traveled to Little Rock, Arkansas, to Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana, and finally to parts of eastern Texas. Southerners thus initially heard only Northern reports of the fight. Their own side’s accounts did not spread until a week or more after the battle, when hard-riding messengers reached the telegraph offices at Little Rock.

Although reports of the battle tended to be highly partisan, those printed in hometown newspapers, North and South, shared important commonalities. In previous wars civilians had waited months to learn the fate of loved ones, but the families of those who fought at Wilson’s Creek obtained information quickly, often within only a few days. Newspapers printed long lists of the names of the killed and wounded in “their” company. Many of these lists were annotated, including the location of wounds and estimates of the sufferers’ chances of survival. As more information became available, lists were updated, expanded, and corrected. Overall, they were remarkably accurate, which meant that while many anxieties were relieved, grief became immediate.

In addition, hometown newspapers often printed letters attesting to the fact that individual wounded soldiers had fulfilled the implicit social contract that had been formed between the community and its company when the men first volunteered. In Embattled Courage, Gerald Linderman notes how Victorian Americans tended to define courage in terms of fearlessness and expected wounded soldiers, even those mortally hurt, to maintain the proper spirit and decorum.22 The soldiers who clashed in Missouri were clearly concerned about courage. In the days following the fight at Wilson’s Creek the survivors reassured their home folk that those who fell in battle had suffered manfully, thereby upholding the reputation of their companies and, by extension, the good name of their hometowns.

The first two weekly editions of Little Rock’s Arkansas True Democrat containing detailed information about the battle illustrate community interest in matters of courage and honor. Accounts of the fighting contained specific information about the behavior of the wounded. A soldier in the Fourth Arkansas Infantry wrote of his friend, “Poor Joe, as he fell, waved his hat to his men, and cried, ‘onward, boys, onward.’” A member of the First Arkansas Mounted Rifles related: “When young Harper fell, they went to him, but he desired them not to stop, but to go on and whip them; and when he learned that we had taken their artillery, he pulled off his hat, gave three cheers, and said he was satisfied. Brown, of the V[an] B[uren] F[rontier] Guards, after he had received a mortal wound, cheered his brave boys to advance.” Dr. Cantrell continued the story, writing that “Harper had become a favorite with the regiment and they thronged around his dying bed to see him and part with him. I could not go near him without feeling almost overcome by the spectacle of his sufferings and his magnanimous disregard for them. Poor fellow! he never murmured or complained once, but died like a soldier and a hero.” Finally, Captain William Woodruff praised a fallen comrade in the Pulaski Light Battery in these terms: “Poor Omer Weaver fell like a hero, with his face to the foe, and died some two hours later, as befits a man. During the fight he refused to get under any shelter at all. No man ever died a more glorious death.” Similar testimony appeared in newspapers throughout Louisiana, Texas, Missouri, Kansas, and Iowa.23

If evidence of such heroism provided solace for the bereaved, many families must have been shocked at the way newspapers reported their loved ones’ deaths in gruesome detail. For example, Franc Wilkie’s widely reprinted account of the engagement at Wilson’s Creek related how Joseph McHenry of the First Iowa’s Governor’s Grays was loading his weapon when “a musket ball tore through his head, scattering his blood and brains upon his comrades on either side of him.”24 It is unlikely that any of McHenry’s friends, on returning to Dubuque, would have used such language to describe his death to his family. For the McHenrys, as for other families across the warring nation, press coverage underscored the cost of war in a far more graphic fashion than was the case in previous conflicts.

Perhaps because death had become so shockingly public, newspaper editors were quick to remind readers of the contributions that the fallen had made to their community. This might be done in an obituary, a formal eulogy, or as part of a larger article. Editors frequently mentioned how long a person had been in the community, his place of employment, civil accomplishments, and surviving relatives. In Iowa, for example, the Mt. Pleasant Home Journal reported the death of former law student Frank Mann, who had resided in Mt. Pleasant only briefly prior to joining the Grays. The editor noted that “in that short time he had made many warm friends. . . . He was a young man of strict morals, rare attainments and of unusual promise.” Likewise, the Atchison Freedom’s Champion in Kansas lauded Camille Angiel, who fell leading Atchison’s All Hazard company. He was, the editor proclaimed, “known to our citizens as a modest, unassuming young man, faithful in the interests of his employer, courteous and genial in social life, industrious and active in his business and duties, and an intelligent and scholarly gentleman.” The Emporia News remarked that Hiram Burt, the only fatality in the town’s Union Guards, was the stonemason who built the local Methodist Episcopal Church. In an article entitled “Martyrs of Freedom,” the Lawrence Weekly Republican eulogized three men of the city’s Oread Guards. “Messers. Pratt and Litchfield were among the very first settlers of the town, and through all the trials and troubles of Kansas were esteemed among the truest friends of Freedom,” wrote the editor. “Mr. Jones leaves a wife now with her father in Olathe, and Mr. Litchfield leaves a wife and child in this place.” For patriotic fervor, none could outdo the resolutions regarding the death of John W. Wood adopted by the Lady’s Sewing Society of Liberty, Missouri, and printed in the local paper. The women declared that the State Guard soldier fell “bravely fighting in defense of our sacred rights, civil and religious liberties, homes and fire-sides, and all that is dear to a free people, and doing battle against usurpation, tyranny and military despotism.” They resolved that “in his death the State lost a good citizen, the neighborhood one of its brightest ornaments, and his home a faithful and affectionate son and brother.”25

Communities recognized the need for continued support of their hometown volunteers. As soon as news of Wilson’s Creek reached Lawrence, two private citizens, James C. Horton and Edward Thompson, left for Springfield to help care for the wounded. “Acts of mercy like this, having no motive but the purest philanthropy, show how deeply such men as Pratt, Jones, Deitzler, Mitchell, and others are entwined in the affections of our people,” commented the Weekly Republican. A citizen of Des Arc, Arkansas, whose name is unknown, undertook a similar mission of mercy, as did Mrs. George Reed, of Emporia, Kansas, who joined her wounded husband in Springfield shortly after the battle. The Fort Smith Times and Herald urged its readers to collect supplies for the wounded: “Gather up shirts, old linen or cotton cloth, and all kinds of delicacies that are generally provided for the sick, fans, sheets, etc. Let every person in town collect all they have of these articles and send them this evening to Major George W. Clarke, the quartermaster, who will at once forward them to the front.” As many residents of Missouri had only a short distance to travel, it is not surprising that they arrived in Springfield in large numbers. Nor was every moment of their time spent in nursing. One soldier recalled, “Ladies whose husbands, fathers, and brothers were in the service, some of them wounded, began to arrive and gave social life and enjoyment to the society of Springfield.”26

Although many of the wounded probably remained in Springfield until December, those less seriously injured were discharged from the hospitals as early as the first week in September. After giving their paroles, wounded Federals traveled to Rolla. Those who had enlisted for ninety days were discharged, whereas most of the others were furloughed to complete their recovery. For weeks after the battle newspapers noted the return of wounded soldiers, lauding their sacrifices and suffering on behalf of the town. Though enlisted men were praised highly, recuperating officers understandably received disproportionate attention. Colonels Robert Mitchell and George Deitzler, for example, were cheered wherever they went in Kansas. With fewer railroads to utilize, most homeward bound Southerners faced a more difficult journey. To facilitate the evacuation of men down the Wire Road McCulloch authorized the impressment of civilian wagons in the Springfield area. Although payment was made for the wagons’ use, citizens were reluctant to surrender their private property to the military. Harris Flanagin recorded the day-long efforts of Mary Phelps to prevent her family’s vehicles from being pressed into service. According to Flanagin, she “would scold and rage until she got tired and then she would cry,” but her protests fell on deaf ears.27

The families of those who lost their lives were deeply concerned with how and where their loved ones were buried. The military authorities had made even fewer preparations for the interment of the dead than they had for the medical treatment of the wounded. On the morning of August 11, soldiers were detailed from the Western Army for a process that was grim psychologically as well as physically. “Battlefields became charnel landscapes, and the hapless soldiers assigned to clean them up became undertakers of the hopes and dreams of many young men far less fortunate than they.” Because of the extreme heat and the size of the job, most of the dead were laid to rest in mass graves, a few even in the sinkhole atop Bloody Hill. The Southerners began with the dead from their own side (assuming they could be identified), leaving Northern corpses for a party of Union soldiers who had remained behind to assist. “The process of burying the dead was toilsome and got on slowly,” William Watson recalled. “By the early part of the forenoon the sun got intensely hot, and some of the bodies began to show signs of decomposition, and the flies became intolerable, and the men could stand it no longer.” A fellow Louisianan also described how the workers quickly sickened “and were unable to finish the task.”28

By the best estimate there were 535 bodies on the field. Each corpse had to be located, identified if possible, and then dragged or carried to a grave site. Digging the grave pits was time-consuming, fatiguing labor in the August sun, yet these difficulties and the unpleasantness of the job hardly excuse the poor performance of the burial parties. If one estimates that it took an average of three man-hours to get each fallen soldier beneath the sod, one hundred men could have completed the task in sixteen hours, the equivalent of two days’ labor. No one knows how many people were assigned to the burial details, but clearly not enough, as the process took much longer than two days. Interments continued through August 12, but when the Union workers did not show up on August 13 (they had apparently departed for Rolla), the Southerners were angered at the prospect of handling the remainder of the enemy’s dead as well as their own. By that time the Western Army was busy shifting to new camps in and around Springfield, so the rest of the Northern corpses were simply left to rot. Most of those thus abandoned were casualties from Sigel’s routed column. A Missouri State Guardsman recalled: “I was a member of a detail of fifty men that was sent over that part of the field to gather up the arms strewn along their wild flight. The stench was awful then, and what it must have been two days later would baffle imagination.” When the Third Louisiana marched past the Sharp farm on August 14, a soldier reported that “the bodies of those that fell in the road near the battery had been thrown to the side of the road and were festering in worms and the advanced state of purification; it was horrible and loathsome beyond description.” Given these conditions, the Sharp family may have evacuated. A full week after the battle a large number of bodies were still reported unburied. According to one account, a captured Union officer, understandably outraged by these circumstances, finally offered civilians $500 of his own money to do the job. Inevitably, some corpses went undiscovered for a long time. Six weeks after the battle young John Short was driving a cow home when he stumbled across a dead Union soldier. The man was probably wounded in the opening phase of the battle and collapsed while attempting to reach Springfield.29

Not all of those who died on August 10 were buried amid the oak hills. The bodies of fallen soldiers who had been natives of Greene County and its environs may have been claimed almost immediately. Others were taken home as well. Besides geographic distance, the greatest determining factor was rank. For example, both Lieutenant Omer Weaver and Private Hugh Byler died while serving the guns of the Pulaski Light Battery. Captain Woodruff went to great lengths to obtain a zinc-lined coffin for Weaver’s body, which was shipped home for a hero’s funeral, one of the largest ever held in Little Rock. Byler, on the other hand, was interred on the field.30

As Nathaniel Lyon was the first Union general to fall in combat, it is hardly surprising that his remains were treated differently from the others, but there was great confusion in the process. Sturgis had ordered the body placed in a wagon, but the vehicle was later taken over to remove the wounded and in the haste of the retreat the general was left behind. As Lyon did not carry a sword and had worn a plain captain’s coat without any insignia of rank, there was little reason for his corpse to be noticed amid so many others. His body was apparently first recognized by Colonel James McIntosh, of the Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles, who removed papers from Lyon’s pockets, either as souvenirs or because they had military value. The Southerners then brought the body to Federal surgeon S. H. Melcher, who had remained on the field after Sigel’s debacle to treat the wounded. Melcher took the body to the Ray home where, with proper military decorum, it occupied a bed while wounded enlisted men from both armies writhed in agony on the hard, blood-soaked floor boards. The privileges of rank went unquestioned, even in death. Nor did Melcher apparently feel any guilt in abandoning his suffering patients when, during the night, he carried the lifeless hero to Springfield under a military escort supplied by General James Rains. The body was placed in Lyon’s former headquarters. There Dr. Franklin’s attempts to embalm it failed because of the extensive internal damage. Since no airtight coffins were available, he ordered an ordinary one of black walnut from a Springfield cabinetmaker. A number of local women sat with the body throughout the night, a typical mourning custom of the times.31

Sturgis and Sigel were understandably preoccupied with organizing the Federal retreat to Rolla, and the column tramped several miles before they realized that their commander’s corpse had been accidentally left behind again. Sturgis sent an armed guard back to Springfield to fetch it, but on arrival they found that other arrangements had already been made. By this time Lyon’s body was decomposing badly, although Dr. Franklin concealed its smell somewhat by sprinkling it with bay rum and alcohol. It was therefore decided to store it in the icehouse at the Phelps farm nearby. The coffin was transported in an ordinary butcher’s wagon, escorted by a detachment of the Missouri State Guard under the command of Captain Emmett McDonald, whom Lyon had captured at Camp Jackson back in May. During the next two days, however, soldiers who were camped in the vicinity threatened to desecrate the remains. To keep it safe Mary Phelps allowed volunteers from the State Guard to bury the coffin in a cornfield on August 13.32

When Lyon’s kinfolk in Connecticut learned of his death, his cousin Danford Knowlton and brother-in-law John B. Hassler made haste for Springfield. General John Frémont sent Captain George P. Edgar, a member of his staff, to assist them in passing through the Southern lines. They had Lyon’s body disinterred on August 23, packing it in ice and placing it in an iron coffin brought from St. Louis. Departing Springfield on August 24, the party made good time. When it reached St. Louis on August 26, Frémont had Lyon’s coffin placed at his headquarters under a guard of honor.33

The next day witnessed the first of a series of ceremonies as the North began to mourn one of the earliest martyrs to its cause. Large crowds went to view the casket, which was transferred to a steamboat with full military honors late in the afternoon. The Adams Express Company contracted to ship the body. Once across the river the remains were placed on a train and conveyed to Cincinnati. There the coffin was on display throughout August 29, attracting many mourners. Entrained once more, the party passed through Philadelphia and New York, where flags flew at half-mast. The coffin arrived in New Haven on the last day of the month and for the next three days was on public view at City Hall. Late in the afternoon of September 3 it went by rail to Hartford, where it rested briefly at the capitol under military guard. Connecticut’s fiery general lay in state, the highest honor the community could render his memory. From Hartford the casket traveled by rail to the town of Willimantic, where a four-horse hearse provided by the state government carried it to the Congregational Church in Eastford.34

The funeral on September 5 was well attended, the procession to the graveyard reportedly a mile and a half long. In one sense this was surprising, as Lyon’s family was not especially well liked locally. His father, Amasa, was an eccentric who had alienated many of his neighbors. Growing up in rural Connecticut Lyon himself had made relatively few friends, and he had visited his hometown but seldom during his adult years.35 The military had been Lyon’s career. Unlike the majority of the soldiers he commanded, he had not participated in the sort of joyous send-offs or emotional flag presentations that had formed tacit social contracts between the soldiers and citizens of Lawrence, Kansas, or Dubuque, Iowa, for instance. But Lyon had done his duty. He had a larger social contract with the nation, written on a West Point diploma, and the people of Connecticut turned out to honor him.