Chapter 19

To Choose Her Own Destiny

Nathaniel Lyon’s original goal had been to stun the superior enemy forces facing him, thus creating contions that would allow the Army of the West to retreat safely to Rolla. When at the last moment he accepted Franz Sigel’s suggestion to attack the Southerners from two directions, Lyon changed his goal, attempting instead to defeat his foe decisively. Lyon failed, and the question remained whether the surviving Federals could escape.

Colonel Sigel reached Springfield on August 10 about 4:30 P.M., well ahead of his men. Riding through the streets half an hour later he encountered Major John Schofield, Lyon’s adjutant general and chief of staff, who told him that Lyon was dead and that Major Samuel Sturgis had just arrived at the head of the troops withdrawn from Bloody Hill. Schofield, in turn, was appraised of Sigel’s disaster. Sigel recommended a council of war, and one was held that evening in Schofield’s quarters. Almost all of the surviving high-ranking officers attended, and they unanimously agreed that the Army of the West should retreat to Rolla without delay. To escape an anticipated enemy attack on the town at dawn, they set the departure time at 2:00 A.M. on August 11. These decisions were hardly unexpected. Indeed, the only surprise occurred when Sturgis passed the command that had devolved upon him at Lyon’s death over to Sigel. Sturgis’s reasons remain a mystery, although his later career suggests that he was never really comfortable with the responsibilities of command.1

As Schofield was now de facto chief of staff for Sigel, he made many of the actual arrangements, including the organization of a train of 370 wagons. Tucked away amid this caravan was $250,000 in specie from the Springfield Bank. He also did everything possible for the comfort and care of the men who were too seriously wounded to be moved. Otherwise, he focused his efforts on readying Sturgis’s column, which, on returning to town, had apparently camped somewhat apart from Sigel’s survivors. Schofield was therefore alarmed when at 2:00 A.M. he discovered Sigel fast asleep and his men completely unprepared to move. Sigel sheepishly announced that he would get his column under way as soon as possible. The march finally began at 4:00 A.M. with Sigel’s men in the lead, but the column was so long that the last Union troops did not leave Springfield until two hours later. A large number of pro-Union civilians left at the same time, fearing the wrath of the Missouri State Guard. According to one eyewitness, “immense panic existed along the route from Springfield.” Had a dawn attack occurred, it would have been a disaster for the Union forces, one chargeable directly to Sigel.2

Forsaking the town did not mean that the Federals were safe. Lyon had feared that the Southern cavalry forces might ride ahead and envelop him during a retreat. Sigel therefore insisted that the Union column make a long march on August 11. The already exhausted soldiers suffered terribly under the blazing sun, and many blamed Sigel’s late start for making things worse than they had to be. Yet Sigel moved so slowly thereafter that the force might have fallen prey to determined pursuers. He also acted as if the German American units from St. Louis were his only responsibility. Instead of rotating the order of march in the column, a standard procedure, Sigel let the Missouri volunteers lead every day. They therefore marched ahead of most of the column’s horses and reached camp first at the end of the day, obtaining the best campsites, firewood, and water. On the third day out of Springfield Sigel halted for three hours while his Missourians slaughtered some cattle and cooked a meal. This delay, and the fact that the food was not shared equally, nearly provoked a mutiny. Schofield reported that “almost total anarchy reigned in the command.” Sturgis had witnessed the growing debacle without interfering, but at the insistence of the other officers he finally resumed command, “giving as his reason for so doing, that, although Colonel Sigel had been for a long time acting as an officer of the army, he had no appointment from any competent authority.” The hasty, unconstitutional methods used by Lyon to raise his forces had come back to haunt the Army of the West.3

After the column reached Rolla on August 19, responsibility for the troops passed to the department commander, General John Frémont. The ninety-day regiments were soon discharged. But for some regiments, such as the First Kansas, the war was just beginning. Whatever the different fates awaiting them, all had participated in a remarkable operation. It was the first major campaign initiated following the outbreak of the war, the second one to be completed. Eugene Ware reported that in its short service the First Iowa, which had left the railway at Renick, Missouri, proceeded on foot to Jefferson City, and after many trials and tribulations finally returned to the railhead at Rolla, had marched 620 miles.4 Many Union units in the eastern theater did not march that far, cumulatively, during the entire four years of the war.

Although Frémont had previously denied Lyon’s requests for major reinforcements, once the news of Wilson’s Creek reached his St. Louis headquarters he burst into action, at least at the telegraph office. He learned of the battle on August 13 and immediately wired the secretary of war, requesting reinforcements from nearby states. The War Department concurred, and appeals went out to Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin. Frémont ordered several regiments already in Missouri to make haste for Rolla, but as in the past he continued to devote most of his time to planning a campaign to open up the Mississippi River. Southwestern Missouri was never his main concern. This is clear from Frémont’s August 30 report to the War Department, in which he forwarded all the after-action reports from the Army of the West. Northern newspapers were busy eulogizing Lyon, but Frémont’s report contained no praise whatever for the Connecticut Yankee, although it did describe him in passing as “brave.” Whereas Frémont lauded the gallant services of a large number of individuals, starting with Sturgis and working down the ranks to some noncommissioned officers, he wrote nothing positive about Lyon’s campaign. His silence implied that the actions of the Army of the West had been pointless, its sacrifices unnecessary.5

Frémont’s negative assessment of Lyon’s actions was understandable. The Battle of Wilson’s Creek did not save Missouri for the Union. Lyon’s real success lay in securing the state’s river and railway communications network. His aggressive campaign disrupted Sterling Price’s attempts to recruit Missouri State Guardsmen, but he also drove them almost literally into the arms of the Confederacy. Lyon’s actions were not judged dispassionately, however. By coincidence, Missouri congressmen Frank Blair Jr. and John Phelps met with Abraham Lincoln at the White House in early August. They predicted disaster as a consequence of Frémont’s indifference to southwestern Missouri, and Lincoln responded by asking the War Department to create a special force under Phelps’s command. Missouri’s largely pro-Union population gave every corner of the state a political value to Lincoln that transcended purely military considerations. When the telegraph brought news of Lyon’s death, Blair and Phelps seemed tragically vindicated. Frémont’s decision not to support Lyon may have had merit from a strategic point of view, but it probably contributed to Lincoln’s subsequent decision to replace him.6

Ironically, whereas Frémont’s fortunes declined before the year ended, Sigel’s career was not irreparably harmed by his rout at Wilson’s Creek and his mishandling of the retreat to Rolla. Across the nation the German American press trumpeted his performance and lavished praise on all those who “fought mit Sigel.” Frémont may have guessed which way the political winds were blowing, for although his report did not praise Sigel above others, it did note his “gallant and meritorious conduct in the command of his brigade.” In fact, Sigel was promoted to brigadier general on August 7, but he learned of it only after the battle, when many questioned his conduct. He resigned during the winter and only later returned to command. Despite Sigel’s military education in Germany, many came to view him as the archetypal political general, a man appointed to command because of his ability to win votes rather than battles. “As a result of the great Missouri campaign, the German leader had made a name for himself. Unfortunately, the name had become synonymous with controversy and retreat.”7

Controversy also marked the actions of the Western Army following Wilson’s Creek. For although the common soldiers of the Missouri State Guard, Arkansas State Troops, and Confederate regiments remained caught up in the euphoria of victory, praising each other’s accomplishments, their leaders were soon at odds. Their difficulties in determining a future course of action were exacerbated by their differing goals, a lack of direction from the War Department in Richmond, and the clumsy structure of the Confederate command system in the West.

Initially things went as well, as one might expect. Ben McCulloch met with Sterling Price as soon as the firing died down on August 10, and they reluctantly agreed that because of their exhausted condition and paucity of ammunition the Southern forces were in no condition to pursue the Federals. Some newspapers later criticized this position and McCulloch eventually published an angry defense of his action. Pursuit proved impossible for almost all victorious Civil War armies, however, and there is no reason to question McCulloch’s decision. The Texan did make an effort to keep track of the enemy. Turning to Greer’s South Kansas-Texas Cavalry, he ordered four companies under Lieutenant Colonel Walter P. Lane to Springfield at dawn on the morning of August n. When they found only wounded Union troops in the town, the horsemen gleefully pulled the Stars and Stripes from the Court House, ripped it to shreds, and raised the regiment’s Confederate banner in its place. Citizens in Springfield with Southern sympathies cheered them on. Two companies of the regiment then scouted the road to Rolla for more than a dozen miles, confirming the Federals’ hasty retreat.8

The Southern commanders spent much of their time on August 11 and 12 shifting the men to new camps. These stretched from Springfield west to Mt. Vernon so the army might live off the surrounding countryside as much as possible. Farmers throughout the region soon responded to the opportunity the soldiers presented, offering a variety of food for sale at prices that were, at least according to one source, much lower than those charged the Federals only days earlier. Some soldiers were not content with the normal channels of commerce, and McCulloch was forced to reprimand his Confederate troops for looting. Significantly, he did so by appealing to their sense of corporate honor. “The reputation of the States that sent you here is now in your hands,” he announced in an order read to the men. “If wrong is done, blame will attach to all. Let not the laurels so nobly won on the 10th instant at the battle of Oak Hills be tarnished by a single trespass upon the property of the citizens of Missouri.”9

Despite the food coming in, the Southerners were nearly immobilized by shortages, as their logistical problems remained acute. They required tons of food daily for their own forces and now had to care for the Union wounded and prisoners as well. The latter group, which numbered less than two hundred, included a woman who had apparently served in the ranks during the battle. An officer in McBride’s Division made a diary entry on August 14 reading: “Saw yesterday a specimen of the Amazonian type dressed in mens clothes. She was captured in uniform & fighting the same as the balance of them.” No other reference or information regarding the woman has been found. Another State Guard officer noted that the German Americans from St. Louis among the prisoners were surprised by the humane treatment they received. Concern about their fate was understandable, not only for recent immigrants, who had historically faced prejudice, but also for the entire group. After all, what should the members of the Missouri State Guard, decidedly pro-Secessionist but still citizens of the United States, do with their fellow Americans who had enlisted in unconstitutional volunteer units and destroyed the legal state government, including its largely pro-Union legislature? Fortunately, some time would yet pass before such complex conundrums plunged the state into a savagery with few parallels in American history. Price and McCulloch decided to simply parole the prisoners. “Missouri must be allowed to choose her own destiny; no oaths binding your consciences will be administered,” McCulloch announced in a public proclamation. His words and action stood in stark contrast to Lyon’s recent fanaticism.10

The experiences of Union prisoners differed widely, of course. Officers were usually treated better than enlisted men. Lieutenant Otto Lademann of the Third Missouri witnessed striking examples of magnanimity and courtesy, but he also encountered stark hostility. On August 11 Bart Pearce invited Lademann and seven other captured officers to dine at his headquarters if they would give their word not to attempt to escape. They readily agreed and greatly enjoyed their meal, having not eaten in forty-eight hours. They spent the night in the camps of the Arkansas State Troops, met with McCulloch the next morning, and were eventually sent to Springfield. Here, their word of honor secured them the freedom of the town. They were paroled a week later and hired two wagons to transport them to Rolla. Near Lebanon the group was stopped by a dozen heavily armed men on their way to Springfield to join the Missouri State Guard. The Southerners had been drinking heavily and one of them called out, “Get out of the wagons, you d—Dutch sons of female dogs, and get in line alongside the road and then you hurrah for Jeff Davis, or you die!” The Federals lined up on the road but refused to cheer for the Confederate president. Lieutenant Gustavus Finkleberg, who had been a St. Louis attorney before enlisting in the First Missouri, argued their case as bona fide parolees, but the jury was not sympathetic. As the situation deteriorated a buggy pulled up containing Emmett McDonald. Once he grasped the situation McDonald pointed two cocked pistols at the would-be State Guardsmen and said: “Boys, I am Capt. Emmett McDonald of General Price’s staff. The first one of you who touches a hair on the head of any one of these gentlemen, I will kill him like a dog. Now go to Springfield and get away from here!” The Southerners “slunk away like whipped dogs,” and after thanking McDonald, Lademann and his companions continued to Rolla without further incident.11

Animosity between enemies was to be expected. But following the battle, ill feeling between McCulloch and Price grew stronger, in part because they assessed future prospects differently. Their divergent views surfaced during meetings held on August 11 and 12. Price argued for an immediate advance into the Missouri River valley, the strategic heartland of the state. If the army remained stationary for long, it would exhaust the rapidly dwindling food and forage available in southwestern Missouri. The city of Lexington made a tempting prize, and the process of recruiting the State Guard could accelerate. Price was not dismayed by the virtual absence of ammunition for the army or the continued presence of large numbers of unarmed men in his own force. Perhaps he remembered how, during the Mexican War, he had used speed and determination to overcome his men’s numerical and logistical deficiencies, successfully suppressing the “rebellion” in New Mexico. If in retrospect Price’s plans were too optimistic, his desire for a swift exploitation of victory, to keep pressure on a beaten foe, was laudable. Moreover, if his chances of reestablishing control over the state were slim, they would rise but little during subsequent years of the war.12

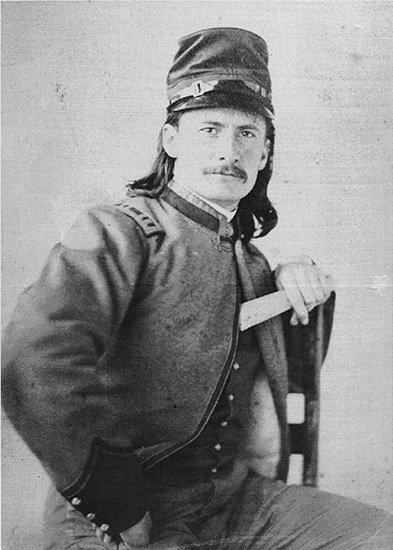

Captain Emmett McDonald of General Price’s staff, Missouri State Guard (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

McCulloch rejected Price’s proposal, partly because he had just learned that the previously anticipated Confederate advance in southeastern Missouri was stalled. Were the Western Army to move north as the left flank of a coordinated Confederate sweep up the Mississippi valley, on both sides of the river, it might be possible to regain the bulk of the state. But he feared that if the army struck out on its own, the operation would degenerate into a fruitless raid. Although it might be easier to forage farther north, the army also required a secure base from which it could receive shoes, clothing, ammunition, and firearms. Price might draw recruits, but how many of them could be effectively armed? A supply line running from Fort Smith to central Missouri would be dependent on wagons, and the length involved made this impracticable. Meanwhile, the enemy could use the railway and river networks both in and adjacent to Missouri to concentrate overwhelming force against the Western Army. When the inevitable retreat occurred, Missouri State Guardsmen—especially those lacking weapons—might desert en masse and be compelled to return home to face the retribution of their Unionist neighbors. Although McCulloch’s objections suggest that he continued to think in the cautious manner that had influenced his operations up to that time, his concerns arose from a competent, professional analysis of the situation.13

Despite the thrill of victory, the Texan was losing patience with the Missourians. Little things added up. Prior to the battle, men from Parsons’s Division had wrongly appropriated a quantity of clothing and almost one hundred tents belonging to the Third Louisiana. These were never returned, nor did either McCulloch or Pearce get back the more than six hundred muskets lent the State Guard from their resources. In fact, the Missourians refused to make an equal distribution of any of the arms and accoutrements policed from the battlefield. Most of these had been salvaged by the unarmed members of the State Guard on the afternoon of August 10. The Missourians were the first to occupy Springfield in force, and when they cleaned out the town’s remaining supplies, they declined to share those either. McCulloch also blamed Price’s men for failing to establish pickets, thus allowing the army to be surprised on August 10. The final straw came when Price had his report of the campaign and battle published in Springfield. Dated August 12 and evidently printed the same day, it was the first official Southern account of the fight. Price quite properly addressed his report to Governor Jackson, but it is unknown whether he submitted a copy to McCulloch simultaneously or the Texan read it for the first time in the newspapers. In either case, the account contained passages that made McCulloch livid. To begin with, Price stated that at Dug Springs “the greater portion of General Rains’s command . . . behaved with great gallantry.” This was hardly an accurate description of the event that the Confederates had dubbed “Rains’s Scare.” Next, Price wrote incorrectly that McCulloch had not exercised command over the combined forces until August 4. When describing the battle, Price naturally focused on the conduct of his own officers and men. He also praised Pearce, the Arkansas State Troops, and the Confederate regiments under Hébert and Churchill. However, other than noting that McCulloch had made “the necessary dispositions of our forces,” he neither lauded his commanding officer nor gave any indication of his contribution to the victory. This omission left the impression that McCulloch’s presence on the battlefield had been irrelevant. Finally, the report implied that the Missouri State Guard had been solely responsible for defeating Sigel and capturing his battery.14

McCulloch had given the artillery captured by the Third Louisiana to the Missourians. But after reading Price’s report, he insisted on its return, explaining that the reputation of Hébert’s men was at stake. Price complied but kept the Union artillery horses. Although Price was being petty, McCulloch was not. The Louisianans had paid for those guns with their blood. They had been publicly insulted by Price’s misleading report, and the restoration of their trophies was necessary for their corporate honor. McCulloch could have used his own battle report as a vehicle of revenge, but he did not. True, he omitted the despised Rains from the list of those deserving credit, but otherwise he praised the Missourians to the same degree he did others. He informed the secretary of war: “Where all were doing their duty so gallantly, it is almost unfair to discriminate. I must, however, bring to your notice the gallant conduct of the Missouri generals—McBride, Parsons, Clark, and Slack, and their officers. To General Price I am under many obligations for assistance on the battle-field. He was at the head of his force, leading them on, and sustaining them by his gallant bearing.” McCulloch, it seems, would deny no man his just due, although he did take pains to indicate that he, not Price, commanded the Western Army.15

In his youth McCulloch might have considered challenging Price to a duel over the wording of the Missourian’s battle report. Now older and presumably wiser, he seems to have been willing to work with Price under any conditions that did not involve risking his own Confederate forces. Yet it was the issue of risk that produced an impasse. Price broke it on August 14 by formally resuming command of the Missouri State Guard. He intended to move west to the Kansas border, to counter a feared “abolitionist invasion,” before heading north to the Missouri River.16

Price’s decision freed McCulloch to concentrate on his original mission: defending the Indian Territory. The challenge was formidable, as within a few days Pearce’s Arkansas State Troops marched south. Those whose enlistments had expired were discharged; the remainder were transferred to Confederate service and assigned to Brigadier General William J. Hardee, as he, not McCulloch, was responsible for Confederate operations in northern Arkansas. Left with only 3,000-odd men, McCulloch soon suspected that his command rated the lowest priority in the entire Southern defense structure. He vented his frustrations in a series of letters to friends, fellow officers, and even President Jefferson Davis. On occasion he railed against the local citizenry for not taking up arms. Fewer than 1,000 Arkansans enlisted in the first weeks following the victory at Wilson’s Creek. These hardly compensated for those who left when their enlistments expired, as almost all the Missourians attracted by the Western Army’s victory chose to serve in the State Guard rather than the Confederate army. “I have called in vain on the people of Arkansas,” McCulloch admitted in a letter to his mother, while to President Davis he complained that “little can be expected of Missouri.” He made an even more negative assessment of the Missourians in a letter to Hardee on August 24, stating: “We have little to hope or expect from the people of this State. The force now in the field is undisciplined and led by men who are mere politicians; not a soldier among them to control and organize this mass of humanity. The Missouri forces are in no condition to meet an organized army, nor will they ever be whilst under their present leaders. I dare not join them in my present condition, for fear of having my men completely demoralized.”17

Such remarks must be placed in context. Though McCulloch’s judgment was harsh, he almost always separated his evaluation of Missouri’s leaders from that of its common soldiers. Two months after his letter to Hardee he informed the secretary of war: “There is excellent material out of which to make an army in Missouri. They only want a military man for a general.” Noting that he himself had become “very unpopular by speaking to them frequently about the necessity of order and discipline in their organizations,” he suggested that should Missouri become a Confederate state, Brigadier General Braxton Bragg might be just the man to calm troubled waters. Even more important, McCulloch’s subsequent correspondence with the Richmond authorities and Price himself indicates his willingness to put aside his needs or opportunities for advancement for the good of the cause. McCulloch could be feisty and critical, but he remained ready to cooperate with the Missouri State Guard in an emergency and was willing to discuss any campaign other than one aimed at a lodgment on the Missouri River. Although McCulloch’s command embraced neither Missouri nor Arkansas, logistics forced him to continue drawing supplies from Fort Smith. Only a small portion of his men actually entered the Indian nations, but the recruitment of Confederate regiments from among Native Americans proceeded apace.18

Operations in the following months were complex, but they can be summarized to place the Wilson’s Creek campaign in the context of subsequent events. Leaving Springfield on August 25, Price’s Missouri State Guard defeated a Union force at Drywood Creek, near the Kansas-Missouri border, on September 2. Price reached the Missouri River on September 13 and soon after laid siege to a Federal garrison at Lexington. At times the Southerners advanced by pushing bales of hemp in front of them, making the engagement unique in the annals of Civil War combat. The Federals capitulated on September 20, and volunteers soon flocked to the cause, swelling the ranks of the State Guard to around 20,000. Yet McCulloch’s dire predictions proved accurate. When Price learned that Frémont was advancing with 38,000 men, he had no choice but to withdraw, as the Missourians had neither the armaments, supplies, nor logistical support system to remain in the river valley. The retreat began on September 29, and the army dissolved steadily with every mile of the march south. By the time the State Guard crossed the Osage River on October 8, there were only 7,000 men under arms. But rather than admit to the inherent flaws in his strategy or question the commitment of his fellow Missourians, Price faulted McCulloch for not supporting him. He also criticized Jefferson Davis, believing that the president’s constitutional scruples prevented Missouri from receiving the attention it deserved.19

The loss of Lexington finally forced Frémont’s attention away from the Mississippi. Yet he advanced slowly, taking time to publish an unauthorized proclamation emancipating Missouri’s slaves. Despite only moderate resistance, the Union forces did not occupy Springfield until October 27. Lincoln was not impressed. He ordered Frémont to rescind his proclamation, then relieved him of command on November 2. Major General David Hunter took over operations against the Missouri State Guard, which continued to retreat toward Pineville, near the Arkansas border.20

A few days before the Federals reached Springfield, Price appealed to McCulloch for help. The Texan responded favorably, partly, no doubt, from a genuine concern for Missourians’ liberties, but also because the Federals now posed an even greater threat to the Indian Territory than they had in August under Lyon. Recent reinforcements brought McCulloch’s force to just over 7,500 men, and he concentrated them along the Wire Road, on both sides of the Missouri-Arkansas border, in a position to move them quickly as needed. Although ready for battle, he was willing to concede all of Missouri north of Springfield to the Federals if they advanced no farther south. For whereas Price looked forward to another victory on the battlefield, followed by a march in unison to the Missouri River, McCulloch favored a more generally defensive stance to allow for continued training and recruitment. He also contemplated the use of partisan warfare and hoped that the Confederate and Missouri State Guard mounted troops might operate together, “destroying Kansas as far north as possible,” as that would provide the best defense for the Indian Territory. The two men were never forced to reconcile their strategies, however, as Hunter, faced with logistical problems almost eight times larger than those Lyon had encountered, retreated after occupying Springfield for only a short time. Lincoln removed him on November 19, giving Major General Henry W. Halleck the top command in the West. In Halleck, Lincoln had a far more learned soldier than Frémont, Hunter, or Lyon, but the Union cause in Missouri never did see Lyon’s equal for drive and energy. Hunter’s departure allowed McCulloch to occupy Springfield, but he withdrew to northern Arkansas early in December to shorten his supply lines. Meanwhile, despite his hope for a return to the Missouri River and the strategic heart of the state, Price marched the Missouri State Guard only some fifty miles north, to a position on the Sac River near Osceola. Within weeks a want of supplies forced him south again. Christmas Day found the Missouri army back in Springfield. Across the Trans-Mississippi theater of the war soldiers began building winter quarters, while their commanders pondered options for the coming spring.21