Chapter 20

Never Disgrace Your Town

The Battle of Wilson’s Creek was part of the complex military and political events of the first summer of the Civil War. But it also occurred within the context of the implicit social contract between the soldiers who fought there and the communities that had raised and supported them. The telegraph rapidly broadcast the news that a major battle had occurred in southwestern Missouri. Once the Union retreat began, Rolla offered the closest working telegraph office. Franc Wilkie and other pro-Union reporters reached there well ahead of Sigel, and their early accounts spread nationwide.1 Because the Federals retreated toward their lines of communication, the news of their activities became more detailed every day. Articles appearing in St. Louis journals were quickly reprinted throughout Missouri, Iowa, and Kansas, but soon the newspapers in all of the states concerned were publishing accounts written by locals who had participated in the fight. Memphis papers picked up many of the Union articles, providing the first details of the battle for Southerners. From Memphis, word of the engagement made its way across the Confederacy. Because the Western Army remained near Springfield for some time and the telegraph lines to the south had been cut, accounts by Southern participants traveled only slowly back to Arkansas, Texas, and Louisiana. And due to the break-down of the mail service, relatively few letters by Missouri State Guardsmen appeared in Missouri papers, regardless of whether the paper was pro-Union or pro-Missouri.

The reaction of communities in Kansas and Iowa exemplifies the response of civilians North and South. Because earlier reports had made it clear that a battle was likely, rumors were widespread in early August, and families felt understandably anxious for their loved ones in uniform. By August 15, most major papers in Kansas had reported Lyon’s death and Sigel’s retreat to Rolla. Few details were available, but the news brought “sadness and painful apprehension to many a Kansas home.” A widely reprinted article from the Leavenworth Times summed up the concern of many: “Two regiments of our brave boys were engaged in the bloody struggle, and many of them, doubtless, have fallen in defense of their country’s flag. Our people will look for details of this battle with the deepest and most intense anxiety.” In Lawrence, flags flew at half-mast and citizens besieged the local post office, “fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters awaiting fearfully every additional report.”2

The first reports of the battle struck Iowa cities like an earthquake. Local newspapers used the word “anxiety” repeatedly in connection with each community’s concern for its company. “At the homes of our gallant boys, the first news created an intense sensation, and many anxious hearts waited to hear the list of killed and wounded,” wrote one columnist. Less than a week after the battle, detailed lists of the dead and wounded were being printed. In Iowa City, home of the Washington Guards, the Weekly State Reporter noted poignantly, “The parents of the two missing soldiers, who reside here, are suffering intense anxiety about the fate of their sons, and we hope that they will soon be heard from.” Occasionally, there was happy news, as men who had been reported dead were discovered to be alive and well.3

Most Northern papers proclaimed Wilson’s Creek to be a Union victory. As by traditional standards of assessment Lyon had been badly defeated, this at first appears inexplicable. Some early reports were simply based on erroneous information. A week after the battle the Atchison Freedom’s Champion referred to “the joyous news of the brilliant victory at Springfield.” A separate article claimed that Sigel had pursued the vanquished enemy until nightfall halted his chase.4 But even after the full details became known, papers continued to refer to Wilson’s Creek as a great victory. How could this be?

In his study of the ill-fated, often defeated Confederate Army of Tennessee, Larry J. Daniel notes how its soldiers evaluated their experiences selectively. Their morale did not collapse because they lauded partial triumphs, celebrating the success of local attacks or stalwart defenses. They were also sustained by a sense of their shared struggle in the face of great odds. Northern assessment of Wilson’s Creek seems to have followed a similar pattern. For example, the Davenport Daily Democrat & News admitted that Sigel had quit the field, but claimed that he had withdrawn of his own free will, “not through compulsion on the part of the enemy.” Even those papers that acknowledged that Sigel had been routed argued that Lyon’s wing had accomplished its mission. Many asserted, wrongly, that the Southern baggage train had been burned, that many thousands of Southerners had been killed, and that Lyon’s death alone prevented the Federals from driving the enemy from the field. They emphasized the odds that the Federals had faced, odds that, due to a lack of accurate information, they greatly exaggerated. “The victory of the Union force under Gen Lyon,” wrote the editor of the Topeka Kansas State Record, “was brilliant and overwhelming; and accomplished under the great disadvantage of having but 8,000 of our troops to make the attack on 23,000 of the Rebels upon their chosen ground and strongly entrenched.” Similarly, the St. Louis Tri-Weekly Republican contended that the “closer the accounts of this battle are sifted, the more certain does it appear that the Federal forces, though vastly inferior in numbers, achieved a most brilliant victory.” Papers in states not directly involved in the action reached the same conclusion. The editor of an Indiana paper counseled his readers: “The battle completely upsets the gasconade heard so often that one Southerner can whip two Northerners. It was a clear triumph on the part of Gen. Lyon’s men. The subsequent night retreat, without pursuit by the enemy, does not change the fact that McCulloch’s army was whipped in the encounter and so the historians will record it.”5

Southern newspapers celebrated with gusto the outcome of the battle they usually called “Oak Hills” or “Springfield.” “Never has a greater victory crowned the efforts of the friends of Liberty and Equal Rights,” wrote Colonel John Hughes of the Missouri State Guard in the Liberty [Missouri] Tribune. “The best blood of the land has been poured out to water afresh the Tree of Liberty.” Another Missouri paper concluded that “as a hand to hand fight its equal is not on record.” Readers of the Shreveport Weekly News were assured that the “Battle of Springfield is only inferior to that of its worthy predecessor, Manassas, in the number of troops engaged,” while Marshall’s Texas Republican boasted that the engagement demonstrated “the superiority of Southern soldiery.” There was remarkably little criticism of the Southern generals for allowing themselves to be surprised in their camps. Instead, harmony among the allies was stressed. The battle was also seen as a vindication of the Missouri State Guard, and Missouri’s eventual secession was confidently predicted.6

If Northern and Southern reactions to Wilson’s Creek were similar, if Northerners could claim victory despite having quit the field, it was because the communities and the soldiers who represented them judged the contest largely in terms of honor. This is clear from contemporary letters and diary entries as well as postwar memoirs. It is even more evident from newspapers, as these served as a vehicle for community self-assessment. They acted as public report cards, first via their editorial commentary, but even more importantly by printing letters from soldiers in the field. In this manner each community’s company was carefully scrutinized.

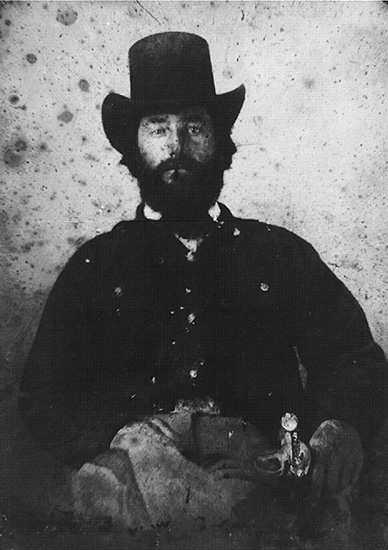

Colonel John Taylor Hughes, Slack’s Division, Missouri State Guard (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Hometown newspapers were quick to proclaim that their community’s honor had been upheld. The Olathe Mirror bragged that the Union Guards had “shown themselves to be worthy sons of Kansas,” while the Atchison Freedom’s Champion boasted that the Kansans had erased the disgrace of the recent Union defeat at Manassas. The editor of the Emporia News wrote of the hometown company, “They have done themselves honor, and we are proud of them.” In Iowa, the Dubuque Weekly Times stated: “The boys have done just what we could have expected when an opportunity presented itself for them to exhibit their daring and bravery. They have met the expectations of their friends.” Pride was not limited to towns that had contributed troops to the battle. The Anamosa Eureka asserted that the First Iowa had “won the chief honors,” outshining other regiments, and the Lyons Weekly Mirror concluded that “the gallant First Iowa have just shown in the desperate struggle in Springfield of what stuff her sons are made.” Southern papers exhibited equal pride in “their” companies. In Liberty, Missouri, the Tribune praised those wounded in Major Thomas McCarty’s company of the Missouri State Guard as “men who went into this war from principle and sealed it with their life’s blood.” The editor continued, “Whilst it causes us infinite grief to hear that some of our brave men were among the killed and wounded, it is yet a source of pleasure to know that they fought like men—like Missourians.”7

As the men in each company knew each other and linear tactics kept them adjacent to their friends throughout the battle, no one’s conduct could go unnoticed. Because the soldiers had pledged their honor in public ceremonies prior to leaving town, no one’s actions went unjudged. The Atchison Freedom’s Champion showed no hesitation in printing a letter that Private Joseph W. Martin wrote to his brother concerning the conduct of the First Kansas: “Some of the boys faltered in the first part of the fight, and three of our company, but none of your acquaintances, they all stood up like men, with but one or two exceptions. Some of the boys say that Keifer, Herman, and Jackell run, and my opinion is that they did, for I did not see them in the fight at all.” Letters written to hometown editors specifically for publication were equally detailed. A civilian correspondent accompanying the First Kansas accused one officer of incompetence, writing that “Major Halderman was so excited as to be of no service in the field.”8

There was obviously praise as well. A soldier in the Third Louisiana informed the editor of the Baton Rouge Weekly Gazette and Comet about the performance of the Pelican Rifles: “They fought bravely and many distinguished themselves. Bob Henderson fought like a tiger. I, myself, saw three of the enemy fall victim to the unerring aim of his trusty rifle. One of them, a U.S. officer, received a ball through the brain. Bob received a blow from a musket in the hands of one of the enemy, who immediately scampered off, but a ball from Bob’s gun lodged between the fellow’s shoulders and caused him to bite the earth.” The writer praised several other individuals by name, concluding, “In fact the whole company, officers and men, fought with a desperation which knew no bounds and won a name for the ‘Pelican Rifles’ which shall not be tarnished in any future engagement.”9

North and South, men seized pen and ink to reassure the home folk that the honor of their regiment and company, and therefore their community, had been upheld. William F. Allen of the Second Kansas wrote proudly to his parents: “Our Reg. was the last to leave the field and stands first in the good graces of the commanding officers. Maj. Sturgis made the remark that if he wanted to storm hell he would take the 2nd Kansas to do it.” Joseph Martin of the First Kansas informed his brother that the last words of his company’s mortally wounded lieutenant had been, “Give it to them, boys; remember your promise to the Atchison folks. Never disgrace your town.” Martin concluded, “Such was the feeling of us all.” A soldier from Olathe, Kansas, wrote, “The Union Guards, or Company G, acted splendidly and fully equalled, if not surpassed, the good opinion formed of them.” In similar fashion, a Texan confided to his sweetheart, “Captain Comby, the other officers, and the entire company from Rusk County acted their part well, and I believe that Rusk County must feel proud that these men represent that county in the Confederate Army.” Another Southerner told readers of his hometown paper in Shreveport, “we turned our faces homeward assured that our conduct as amateur soldiers would never be a source of reproach to our friends in Caddo [Parish].”10

Officers naturally took pride in the conduct of the men under their command. Colonel John R. Gratiot informed Arkansas readers of the Washington Telegraph, “Our Hempstead boys did their work nobly, and fully sustained the good name of their city, and were during the whole fight in the hottest of the fire.” Louisiana captain John P. Vigilini basked in the praise that Ben McCulloch had lavished on his men, writing that “the Pelican Rifles are worthy of all honors bestowed upon them.” He concluded that “Baton Rouge may well be proud of those who represent her in the great struggle in the southwest of Missouri.” Lieutenant C. S. Hills of the Second Kansas asked the editor of the Emporia News to reassure the makers of his company’s flag that “it has not been disgraced.” He continued: “I feel proud of our little Emporia company—of the regiment—of the State we came from. The State shall never be disgraced by us.”11

Communities also took an interest in how their units appeared in the official reports, which were published within a month of the battle. Because the reputations of both men and entire communities were at stake, it is perhaps not surprising that controversies arose following Wilson’s Creek. As Lyon was the first Union hero of the West and one of the war’s first martyrs, associations with him were both treasured and disputed. Newspaper correspondent Thomas Knox recalled, “I know at least a dozen individuals in whose arms Lyon expired, and think there are as many more who claim that sad honor.” Members of the First Iowa denounced reports by the First Kansas that Lyon had been leading that regiment at the time of his death, claiming the honor for their own unit. Members of the Second Kansas and First Missouri made like assertions. The controversy, which was picked up by the national press, continued among veterans long after the war. In a related matter, Colonel George Deitzler of the First Kansas used the Kansas and Missouri press to denounce the official report of Lieutenant Colonel William Merritt of the First Iowa, which had appeared in the St. Louis papers, because it stated that the Kansans had retreated in confusion.12

Some controversies were personal. For example, the Atchison Freedom’s Champion, which had reported the movements of the city’s All Hazard company in great detail throughout the campaign, took pains to defend the reputation of its commander, Captain George H. Fairchild, who had departed Springfield on furlough on August 9. The paper’s claim that Fairchild had not anticipated a battle and left merely to attend to pressing personal business affairs was hardly creditable. Perhaps to ward off any suggestion of cowardice, the paper emphasized Fairchild’s intention to remain in the service for the duration of the war. Colonel John Bates, the unpopular commander of the First Iowa, also missed the battle. Although some papers attributed this to a fever, correspondent Franc Wilkie’s reports implied that Bates was drunk. Bates never offered a direct public defense, but Captain George Streaper of the Burlington Zouaves turned to the pages of his hometown paper to defend his reputation. Cashiered prior to the battle, Streaper claimed that “Col. Bates and my 1st Lieut., being determined to detach me from my company, were the whole cause of my detachment.” More than a dozen officers from nine of the regiment’s companies publicly endorsed the captain’s claim. In a somewhat similar case, thirteen officers of the Fifth Missouri wrote the St. Louis Tri-Weekly Republican to defend their commander, Colonel C. E. Salomon, against charges of cowardice that had appeared in a German-language paper.13

Despite his retreat, Sigel garnered as much praise as criticism for his performance at Wilson’s Creek. Indeed, many Federals who had been in Lyon’s column blamed Sigel’s soldiers for the debacle rather than Sigel himself. Sigel’s reputation among German Americans continued to climb, while Lyon’s superior, department commander John C. Frémont, was frequently criticized for not sending reinforcements to Lyon. In at least one important instance the battle healed rather than provoked controversy. Papers throughout Kansas praised Deitzler’s conduct during the battle, reporting that it erased the ill feelings engendered by the whipping of the volunteers en route to Springfield.14

Perhaps because Southerners were caught up in the afterglow of victory, there were no major controversies on their side. Although arguments later arose concerning McCulloch’s decision to withdraw to Arkansas, leaving Sterling Price to fight alone at Lexington, the different elements of the Western Army generally praised each other in the days immediately following Wilson’s Creek. Indeed, the conduct of the Missouri State Guard won the admiration of many who had questioned its pugnacity since the skirmish at Dug Springs. “The Missourians, who were looked upon by the Confederate army as dastardly cowards, most gallantly retrieved their characters on that day,” wrote a Louisiana soldier. The Reverend Robert A. Austin, chaplin of Slack’s Division, spoke for many Southerners when he observed, “The Louisiana troops, the Arkansans, the Texans and Missourians stood side by side and fought only as men can fight when fighting for their honor and their homes.”15

All of the men who fought at Wilson’s Creek received accolades from their home communities. But because they had enlisted for only ninety days, the returning survivors of the First Iowa and Second Kansas were able to participate in various public meetings, dinners, and receptions that truly validated the social contract they had established with their hometowns at the beginning of the campaign. Although the North held victory celebrations in 1865, the length and devastation of the war made that triumph bittersweet. But in August and September 1861 it was still possible to believe in a short war and even envy those who had served. Few American soldiers have ever received such profound thanks and adoration as did the Iowans and Kansans who made their way back to hearth and home.

The men of the First Iowa made a relatively speedy return, their jubilation increased by the fact that the entire regiment now wore matching gray uniforms and new shoes, which they had found waiting for them at Rolla. They were officially discharged at St. Louis on August 23, and a flotilla of steamboats brought the regiment to Burlington two days later. Twenty thousand civilians jammed the levee, many straining to identify the wounded, who disembarked first. As they had throughout their service, the companies strictly maintained their separate identities, even in the midst of celebration. Initially only the Burlington Zouaves, Mt. Pleasant Grays, and German Rifles were to have gone ashore to attend the great public feast that had been prepared. The remaining companies were invited to join the festival at the last minute. “We were honored like the return of a Roman Legion after the conquest of a new empire,” one veteran recalled of the march through town. Not surprisingly, Governor Samuel Kirkwood was on hand to give a speech. He had his work cut out for him as the First Iowa’s second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel Merritt, was soon touted in the press as a potential rival for the gubernatorial chair.16

From Burlington, the companies traveled by rail or steamboat to their home cities, where, without exception, they received a lavish welcome. In Iowa City, notices had been posted on August 21 for a meeting to plan a reception for the Washington Guards. In one evening over $1,800 was pledged to support the endeavor. Muscatine held an enormous parade for its two companies, with not only the soldiers, but also the men, women, and children of the town participating. At the public banquet that followed, the first toast of the evening praised the soldiers for having upheld the honor of the state. In Dubuque, ten thousand people lined the streets as the Wilson Guards and Governor’s Grays marched past. Dozens of homemade banners stretched across the street bore such slogans as “Honor the Brave,” “We Are Proud of You,” “Welcome Brave Boys,” and “Iowa First, Tried and Found True.” The parade halted at the center of the city park, where rows of young girls, dressed all in white, presented each soldier with a bouquet and a wreath of oak leaves. The inevitable speeches, in both English and German, followed before the soldiers finally sat down to an outdoor dinner. The Weekly Times, which reported the proceedings under a subheadline reading “Honor to the Brave, and Honor to Dubuque,” proclaimed that the conduct of the two companies had reflected a glory on the whole town that would be passed down for generations. When the steamer bearing Captain August Wentz and the German Volunteers came into view of Davenport, the soldiers crowded the decks, breaking into spontaneous song and dance. On landing, they found not only the levee crowded, but also every rooftop and balcony along their projected parade route filled with citizens who showered them with flowers and oak leaves. They passed through three triumphal arches. The first of these had been constructed entirely by German American women, and the second two were decorated by them. Banners welcomed home the “Pride of Iowa.” The citizens inland at Mt. Pleasant had decorated in a rush, only to find the train carrying their Mt. Pleasant Grays two days late. The city’s celebration was elaborate and joyous, nevertheless.17 Meanwhile, in the Mt. Pleasant Home Journal, as in newspapers across the state, bad verse sprouted like dandelions as amateur poets vied to honor the gallant First.18

For the Kansans, celebration began when they reached St. Louis. The two regiments camped in a local park, and the men were allowed to roam the city at will. One soldier recalled, “Abundance of everything to eat was free to them, and no saloon in town would charge a cent for beer to a soldier who had Tought mit Sigel.’” Most of all, they were anxious to return home. The men of the Second Kansas anticipated their discharge, while those in the First Kansas hoped for furlough. Most of the latter were disappointed, although a number of wounded men had been sent directly to Kansas shortly after the battle. They were universally lionized, and in this manner the First Kansas received tremendous public praise, even though the regiment remained in the field.19

During the last weeks of August newspapers throughout the state announced the imminent return of the Second Kansas and urged readers to make appropriate preparations for the soldiers’ welcome. In Topeka, the Kansas State Record declared that “they must have such a public reception as will be a deserved tribute to their courage and endurance.” Another paper echoed these sentiments, writing: “Shall the boys have a public reception? Every citizen will answer yes. Let us get up a meeting and take measures to give them a public and hearty reception. They deserve it at our hands.”20

The trip home began auspiciously for the men of the Second Kansas. General Frémont gave them a personal salute in front of his St. Louis headquarters and authorized them to emblazon “Springfield” on their regimental colors in honor of their gallant service. But tragedy struck on September 2, as the train bearing the regiment to St. Joseph derailed at a bridge crossing the Platte River. Eight persons were killed, including Lucius J. Shaw, a Vermont native and Dartmouth College graduate, who had enlisted as a private in the Leavenworth Union Rifles and was subsequently elected lieutenant. Reports blamed the wreck on pro-Secessionists in the area.21

The Kansans remained at St. Joseph for more than a week. Then, despite fighting that raged at Lexington only a short distance away, they were ordered to Fort Leavenworth. Boarding the steamer Omaha, the men doubtless assumed that they were leaving danger behind them for good, yet early on the morning of September 15, near Iatan, Missouri, they sighted “a body of rebel cavalry” lining the shore. After an exchange of bloodless volleys the enemy fled, allowing the Kansans to claim their very last military action as a victory.22

Elaborate preparations had been made for a reception at Leavenworth honoring the entire regiment. “Although but two companies can be claimed by Leavenworth, the regiment is of Kansas, and well has it maintained the honor of our young State since it left us,” explained the editor of the city’s Daily Times. As the soldiers were expected to arrive during the evening of Sunday, September 15, there was considerable consternation when, just before 10:00 A.M., worship services were disrupted by a cannon’s discharge, signifying that the Omaha was in sight. Soon fife and drum music could be heard from the vessel’s deck, and crowds of citizens rushed to the levee to greet loved ones as the companies marched onto shore.23

The men and women on the celebration committees reportedly did a fine job of adapting to the changed circumstances, and everyone had a good time in spite of cloudy skies and occasional drizzle. The men of the Second waited patiently on the levee for two hours while the local militia and Home Guard companies assembled. Then a short parade, which began around noon, brought the multitude into the center of town where speeches were made from the steps of the leading hotel. In place of the public banquet that had been planned for that night, the soldiers were treated to meals at three local restaurants. By mid-afternoon tents had been unshipped, and the men were camped just outside the city in the same location they had occupied the previous June when assembling to go to war. Visitors wandered through the camp well into the night. Unlike the Iowans, the men of the Second Kansas had never received replacement uniforms, and their ragged appearance was a source of much comment. “In truth, the men looked rough,” noted one observer.24

From Leavenworth the Second Kansas expected to go to Lawrence. That city’s own Oread Guards—the “Stubbs”—were still serving in Missouri with the First Kansas. But there was a long-standing rivalry between Lawrence and Leavenworth, and the citizens of Lawrence were determined to give the Second the finest reception possible. Hundreds of posters and handbills announced the forthcoming celebration, at which “Lawrence expected to see the grandest day of her age.” Farmers brought food by the cartload, while sugar and coffee were stockpiled “by the hundred weight.” The women of the community labored for hours to prepare a feast worthy of heroes. Then, on the evening before the regiment was scheduled to appear, word arrived that it had been ordered to Wyandotte instead. There the regiment was broken up, the men furloughed until the expiration of their enlistments at the end of October. Disappointment in Lawrence was acute. Over the course of several days they feasted individual companies that passed through the town en route to their homes, but it was not the same.25

So the Kansans made their way back to Topeka, Olathe, Burlingame, and other communities, garnering even more praise from friends and relatives. The homecoming of the Union Guards was especially poignant. After an absence of 158 days, they marched down the streets of Emporia on Saturday, October 19, to “a welcome that did the very soul good.” As their arrival had not been foretold, the town’s reception committee postponed the official celebration until Tuesday evening. It included all of the standard elements—a parade, military music, speeches, and a public feast—but its high point was something special. The Guards had begun their military service at a public ceremony in May, receiving a banner constructed by the ladies of Emporia and being blessed by Father Fairchild, the town’s leading minister. Out of the ten Second Kansas company flags so fashioned by home folk, theirs had been selected as the regimental colors, and theirs alone had actually been carried on the battlefield at Wilson’s Creek. The soldier who had received the flag that day in May, pledging along with his comrades to uphold the honor of Emporia, lay buried in the soil of southwestern Missouri. Three of his comrades had also failed to return, and another seven were wounded, a casualty rate of one out of every four of the town’s volunteers. As a tribute to them the flag was returned to Emporia and consecrated to their memory.26

The ceremony took place in the local Christian Church, with the aged Reverend Fairchild presiding, his long white locks spilling onto the collar of a shabby formal black coat. Mrs. Anna Watson Randolph, who helped to sew the flag, described the service as the Second Kansas arrived:

Sadly they marched up the aisle. Father Fairchild, who had prayed over them and blessed them and sent them to battle such a short time ago, received them with tears rolling down his wrinkled cheeks. They placed their flag in his hands. He unfolded it. We saw it full of bulletholes, ragged and battle-stained. He pointed to the dark stains on the staff where the blood of our brave young soldier had trickled down, and told us how even in the struggle of death he had borne it up until a comrade could take his place. . . . We sobbed and cried aloud. It was our first experience of the horrors of war.27

The Kansans and the Iowans had come full circle in their social contract. Sent forth from their hometowns, they had returned with their own honor as well as that of their communities intact. Honor also had been maintained by the other Northern and Southern veterans of Wilson’s Creek whose enlistment kept them in the ranks. Had their hometowns been given the opportunity, doubtless they would have treated them just as grandly. But for them, as for so many other soldiers and their families across the land, the war was just beginning.