Epilogue

A Heritage of Honor

It is hardly surprising that the accomplishments and fortunes of those who fought at Wilson’s Creek differed widely following the battle. For nineteenth-century Americans these variations were evaluated in the context of honor. As Bertram Wyatt-Brown notes, honor and reputation were two sides of the same coin. Honor was linked to public perception, making what people thought of one another extremely important. Yet opinions might differ. Franz Sigel continued to display the odd combination of military talent and ineffectiveness that had brought him adroitly to a key position on the battlefield at Wilson’s Creek only to fail by neglecting his security. He fought with both skill and ineptitude during the Pea Ridge campaign in 1862 and was promoted to major general. German Americans worshiped him throughout the war, even after his defeat at New Market, Virginia, in 1864 and removal from command. Sigel was a journalist for a short time after the fighting ceased but soon became heavily engaged in politics and held a number of minor positions during his remaining years. Although Samuel Sturgis became a major general of volunteers, his wartime career effectively ended in Mississippi at Brice’s Cross Roads in 1864, when he proved to be no match for Nathan Bedford Forrest. In the postwar period, with his permanent Regular Army rank of colonel, Sturgis initially commanded the Sixth Cavalry and later the Seventh Cavalry. The latter assignment introduced him to a brash subordinate named George Armstrong Custer, who led the regiment on active operations while the colonel sat behind a desk. Sturgis retired in 1886. Fate forced Ben McCulloch and Sterling Price into close partnership once again, as wing commanders under Earl Van Dorn, at Pea Ridge, Arkansas. McCulloch was killed while trying to get a better view of the enemy’s position. Price survived, enduring not only the Confederate defeat at Pea Ridge but also failures at Iuka and Corinth after being transferred across the Mississippi. Back in Missouri in 1864, he led the largest and longest cavalry raid in American military history. When the war ended Price initially chose exile in Mexico rather than surrender, but he returned to Missouri in 1866 and engaged in civilian pursuits. Bart Pearce exchanged his Arkansas state commission for the rank of major in the Confederate commissary department, serving in Arkansas and Texas amid accusations of graft and corruption. After the war he pursued a variety of business activities and was briefly a professor of mathematics at the University of Arkansas.1

Almost two dozen veterans of Wilson’s Creek achieved the rank of general in either the Southern or Northern army. A few examples will illustrate the diversity of their experiences. Joseph B. Plummer became a brigadier general and served with Major General John Pope, but he died in August 1862. John M. Schofield, Lyon’s chief of staff, rose to major general, commanded a corps, and won a major defensive victory at Franklin, Tennessee. He acted briefly as secretary of war under President Andrew Johnson and ended his career as the army’s general-in-chief, eventually attaining the rank of lieutenant general. Gordon Granger, who had advised Union soldiers to hide in the grass and aim low, won fame as a major general at Chickamauga, Georgia, and later commanded a corps. He served in the peacetime army until his death. Francis J. Herron, onetime captain of the Governor’s Grays in the First Iowa, earned a brigadier’s star and much later the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroism at Pea Ridge. When promoted to major general in 1863 at age twenty-six, he was then the youngest two-star officer of the war. Yet in peacetime he was unsuccessful in business and died in poverty. One-armed Thomas W. Sweeny, who had been unofficially elected brigadier general by the Missouri volunteers, became a brigadier in fact in 1863. A division commander during the Atlanta campaign, his poor performance led to a court-martial and despite an acquittal his career came to an end. Prior to his death in 1892, he was involved in the Fenian movement. Eugene A. Carr, whose poor performance at Wilson’s Creek was mixed with a suggestion of cowardice, or at least loss of nerve, ended the war a major general. Like Herron, he won the Medal of Honor for heroism at Pea Ridge. Carr served for almost thirty years in the Far West, where his “exploits were legion.” After retiring in 1893, he was active in the National Geographic Society.2

James Patrick Major, whose Missouri State Guard troopers had fled from Sigel’s surprise bombardment, went on to fight at Vicksburg in Mississippi and at Mansfield and Pleasant Hill in Louisiana. He finished the war as a brigadier general commanding cavalry and spent the postwar years as a planter in Louisiana and Texas. John T. Hughes, the State Guard colonel who had argued that the Tree of Liberty must be watered with blood, became an acting general and died leading an attack on Independence, Missouri, in 1862. Death also claimed James M. McIntosh, who had resigned from Sturgis’s command in Arkansas during the first weeks of the conflict and later directed the fight in John Ray’s cornfield. Promoted to brigadier general, he was killed within minutes of succeeding to the command of McCulloch’s Brigade at Pea Ridge, only a few hundred yards from the spot where his Texas chief fell. Dandridge McRae, who had assisted in organizing the Arkansas State Troops before accepting his Confederate colonel’s commission, fought at Pea Ridge and won promotion to brigadier general. He served in campaigns throughout the Trans-Mississippi and practiced law after the war. Louis Hébert led the Third Louisiana at Pea Ridge, where he was captured. After being exchanged, he was promoted to brigadier general and fought in Mississippi at Iuka, Corinth, and Vicksburg. In peacetime he was a teacher and newspaper editor. Matthew Ector of the South Kansas-Texas Cavalry, who had become separated from his son Walton during the fighting in Sharp’s fields, was later commissioned a brigadier general and fought at Chickamauga, but, severely wounded in the Atlanta campaign, he saw little further service. After the war Ector was a state court judge in Tyler, Texas. Others attaining the rank of general included Peter J. Osterhaus, George W. Deitzler, Robert B. Mitchell, Powell Clayton, Frederick Steele, David S. Stanley, Karl L. Matthies, Thomas P. Dockery, Elkanah Greer, Walter P. Lane, and Thomas J. Churchill.3

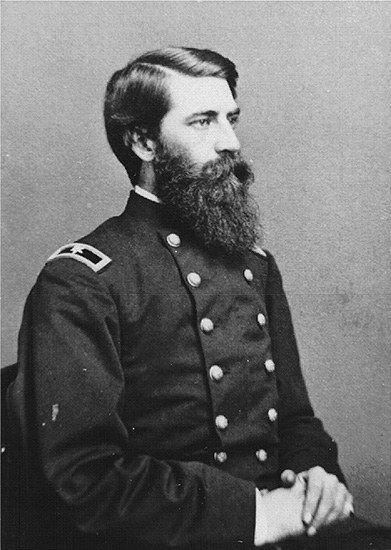

Although the Congressional Medal of Honor was instituted during the Civil War, many awards were not made until long after the conflict ended. The five men decorated for their conduct at Wilson’s Creek were all honored in the final years of the nineteenth century. The first medal went to Lorenzo Immell in 1890 for his “bravery in action” with Totten’s Battery. Immell received a lieutenant’s commission shortly after Wilson’s Creek and served in a number of artillery units. He was acting inspector of artillery for the IV Corps when the fighting ceased. In 1892 Schofield, then the army’s senior officer but not yet promoted to lieutenant general, was awarded the medal for being “conspicuously gallant in leading a regiment in a successful charge against the enemy.” The next year Henry Clay Wood, a native of Maine and graduate of Bowdoin College, was so honored. A first lieutenant in the Regulars at Wilson’s Creek, he was cited for “distinguished gallantry.” Remaining in the army until 1904, Wood retired as a brigadier general. In 1895 the medal went to William M. Wherry, who as a first lieutenant in the Missouri volunteers “displayed conspicuous coolness and heroism in rallying troops that were recoiling under heavy fire.” Wherry, who also fought at Atlanta, Franklin, and Nashville, was commissioned a brigadier general of volunteers during the Spanish-American War. The final medal given for exceptional service at Wilson’s Creek was issued in 1895 to Nicholas Bouquet of the First Iowa’s Burlington Rifles. Bouquet had risked his life assisting Immell in rescuing the caisson from Totten’s Battery.4

Lieutenant Henry Clay Wood, Eleventh U.S. Infantry, awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. A post–Civil War photograph. (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Postwar medals were not available for Southerners, nor did Federal tax dollars support them in their old age. The contrast between victor and vanquished during the American Civil War may have been modest when compared to some of history’s other great internecine struggles, but when viewed at the level of individuals it could be severe. For example, in the same decade that Immell, Schofield, Wood, Wherry, and Bouquet were honored, dozens of veterans of the Missouri State Guard showed up on the doorsteps of the state-run Confederate Home at Higginsville. The home’s application book recorded their histories only briefly, but its testimony is poignant. Indigent veterans of Wilson’s Creek included fifty-year-old T. A. J. Worsham, who as a lad of twenty had lost his left leg charging up Bloody Hill as a member of Weightman’s Brigade. One-armed John F. Peers, who applied for residence at age seventy-six, had been a cavalryman in Rains’s Division. Rheumatism, a term that in the nineteenth century covered a host of ills, was the reason most often cited by applicants for their inability to support themselves and their families. One such sufferer was Albert G. Ball, fifty-six in 1891, who first saw action in the State Guard at Carthage and went on to fight in ten subsequent battles, including Wilson’s Creek, Lexington, Iuka, and Corinth. He was unable to provide for his wife and three sons, the youngest of whom was fourteen. Stephen W. Hall, another veteran of Rains’s Division, applied two years later because he was nearly blind at age fifty-six. A widower, he had two sons and a daughter.5

Lieutenant William M. Wherry, awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Individual achievement is significant and individual tragedy is moving, but the men who fought at Wilson’s Creek continued to think of themselves largely in terms of their old units and what they had accomplished corporately. This was particularly true from 1881 onward. Across the nation, the twentieth anniversary of the beginning of the war was marked by a dramatic increase in veterans’ activities. Because Wilson’s Creek occurred so early in the conflict, it was the focus of much of the initial commemoration of the war west of the Mississippi. Organization took time, and although there was a wide variety of local activities, a joint reunion of Northern and Southern veterans was not held on the battlefield itself until 1883.6

The surviving participants of the war shared a heritage of honor, regardless of whether they had served in the Federal or Confederate armies, the Missouri State Guard, or the Arkansas State Troops. The best example of what the fight at Wilson’s Creek meant to these men can be found in Kansas. In 1879 veterans organized the Society of the Kansas First, and as time went on newspapers across the state printed increasing numbers of articles about their activities. But if Kansans in general were proud of their former soldiers, pride ran highest at the community level, just as it had during the war. On August 10, 1881, the Atchison Champion printed a brief history of the All Hazard company, which had marched from the town’s dusty streets two decades earlier. Most significant of all, the article also included in large print and block letters the following names:

JAS. ERWIN, ISAAC DENTON, FRANK GERRLISH, JACOB N. KROUK, MICHAEL KATZ, ADAM MAY, WILLIAM REGAN, FRANCIS M. SHOWALTER, THOS. J. W. TARR, PHILIP WILBERGER, LUTHER MCCLENDON, JAS. MCBRIDE, WILLIAM STEWART, JNO. STRATTON.

They were identified as Atchison soldiers who had deserted the First Kansas.7 Having broken the social contract between the community and its soldiers, having disgraced their town, their sins could never be forgiven.