CHAPTER FOUR

Greater Senegambia/ Upper Guinea

The blacks of the rivers and ports of Guinea ... we refer to, because of their excellence, as of law [having a written religion with ethical-legal traditions]. They are much more faithful than all the others, of great reason and capacity, more handsome and attractive in appearance; strong, healthy, and capable of hard work; and for these reasons it is well known that all of them are more valuable and esteemed than any of the other nations. These peoples and coasts are numerous, and referring to all of them would be an exhausting and infinite task. But giving some information about them would be pleasant, advantageous, and even very necessary to our task. Among them are Wolof, Berbese, Mandinga, and Fula: others Fulupo, others Banun; or Fulupo called Boote; others Cazanga and pure Banun; others Bran; Balanta; Biafara; and Biofo; others Nalu; others Zape; Cocolis and Zozo.

-Alonso de Sandoval, Un tratado sobre la esclavitud, 1627.

This chapter challenges some of the prevailing wisdom among historians who minimize the demographic and cultural contribution of peoples from Greater Senegambia to many important regions in the Americas. During the first 200 years of the Atlantic slave trade, Guinea meant what Boubacar Barry defines as Greater Senegambia: the region between the Senegal and the Sierra Leone rivers. In Arabic, “Guinea” meant “Land of the Blacks.” It referred to the Senegal/Sierra Leone regions alone. In early Portuguese and Spanish writings, “Guinea” meant Upper Guinea. Early Portuguese documents and chronicles called the Gold Coast, the Slave Coast, and the Bights of Benin and Biafra the Mina Coast.

1 In the writings of Alonso de Sandoval, “Guineans” meant Greater Senegambians. As late as the nineteenth century, “Guinea” continued to mean Upper Guinea to other Atlantic slave traders as well. When King James I chartered the first English company to trade with Africa in the early seventeenth century, the Portuguese and Spanish usage of the term “Guinea” was initially adopted. The English company was named the Company of Adventurers, and it was to trade specifically with “ ‘Gynny and Bynny’ (Guinea and Benin).”

2 After the northern European powers began to enter the Atlantic slave trade legally and systematically in the 1650s, “Guinea” was gradually extended to mean the entire West African coast from Senegal down through Angola. But the meaning of “Guinea” continued to depend on time and place and was far from precise or universal. It often continued to mean Greater Senegambia among Iberians and at times among Atlantic slave traders of other nations as well. A French document dating from 1737 ordered a ship to go to Africa and get slaves from “the Coast of Guinea or elsewhere.”

3 There is credible evidence that as late as 1811 “Guinea” or the “Coast of Guinea” still referred to Africans from Sierra Leone.

Map 4.1. Greater Senegambia/Upper Guinea, 1500-1700. Adapted from a map by Boubacar Barry, in UNESCO General History of Africa, vol. 5, ed. B. A. Ogot (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992); copyright © 1992 UNESCO.

Greater Senegambia is much closer to Europe and North America than any other region of Africa. Voyages were much shorter. The earliest Atlantic slave trade began in this region. Half a century before the “discovery,” conquest, and colonization of the Americas began, African slaves, mainly Senegambians, were brought to Portugal by ship, sold in the active slave market in Lisbon, and then resold throughout the Iberian Peninsula. The earliest information we have about them comes from Valencia, Spain. Their “nation” designations have been interpreted as regional rather than ethnic, cultural, or linguistic. They include “Guine,” “Jalof” (Wolof), and, by the 1490s, “Mandega” (Mandingo). The Mandingo were Mande language group speakers, descendants of the peoples of the Mali Empire who were prominent conquerors, traders, and interpreters of languages throughout Greater Senegambia. Many speakers of West Atlantic languages had been conquered, displaced, and/or acculturated by Mande language speakers.

4 African ethnicity and regional names overlapped. According to Stephan Buhnen, in these documents “Jalof” meant all of northern Upper Guinea, “Mandega” meant central Upper Guinea (from the Gambia to the Rio Geba), and “Sape” meant southern Upper Guinea (to the Sierra Leone River).

5Many enslaved Africans brought to the Iberian Peninsula and their descendants were converted to Christianity and spoke Portuguese and/or dialects of Spanish. The Wolof were prominent among them.

6 They were referred to as “Ladinos,” meaning Latinized Africans. After the conquest and colonization of the Americas began, enslaved Africans continued to be introduced into the Iberian Peninsula. They and their descendants were among the first Africans and peoples of African descent brought to the Americas as “Ladinos.” The comparatively rapid voyages from Greater Senegambia to the Caribbean encouraged populating early Spanish America with Africans from Greater Senegambia.

The earliest importation of enslaved Africans to Spanish America was to the island of Santo Domingo in 1502. After the conquest of Mexico in 1519, Mexico (New Spain) became an important destination as well. In keeping with Spain’s laws and policies enforcing religious conformity throughout its empire, the first African slaves brought to Spanish America were Ladinos. But the Ladino slaves encouraged and helped the surviving Arawak Indians of Santo Domingo to rebel against the Spanish colonists. Hoping to bring in slaves who were more ignorant of Spain and Spanish ways and therefore less dangerous, the Spanish began bringing in enslaved Wolof from Africa instead of Ladinos, despite the fact that the Wolof were Islamized. But they turned out to be as rebellious as the Ladinos. They, too, encouraged and helped the Arawak to revolt against the Spanish and became repeatedly and universally prohibited in Spanish America. Nevertheless, Wolof continued to arrive in substantial numbers.

7

Table 4.1. Length of Slave Trade Voyages Arriving in Cartagena de Indias, 1595-1640

Source: Calculated from Vila Vilar, Hispanoamerica y el comercio de esclavos, 148-52. Note: The length of slave trade voyages begins with their departure from Europe and includes the voyage to West Africa, time on the West African coast, the voyage across the Atlantic to the Americas, and the return to Europe.

During the closing decades of the sixteenth century, the Portuguese lan (ados gradually established a fortified slave-trading post on the Cacheu River in Greater Senegambia

8The catchment area of this post was referred to in Portuguese documents as the Rivers of Guinea. In Spanish and Portuguese documents, “Ríos de Guinea” meant the region between the Casamance and the Sierra Leone rivers.

Although Brazil is widely associated with West Central Africa and the Slave Coast, Greater Senegambia was an important source of Africans brought to Brazil. Costa e Silva has called the last half of the sixteenth century the Guinea phase of the slave trade to Brazil.

9 Dutch and then French and British slave traders largely displaced the Portuguese in Greater Senegambia during the seventeenth century, but Portugal maintained a relatively minor presence at its trading posts of Cacheu and Bissau. During the last half of the eighteenth century, far northeastern Brazil was colonized and developed with Africans from Greater Senegambia. The Maranhão Company was chartered in 1755 and held a monopoly of the Portuguese and Brazilian slave trade from Upper Guinea for twenty years. Its slave trade brought Africans mainly to Maranhão and Para in northeastern Brazil, a rice- and cotton-producing region located in the North Atlantic system of winds and currents. It was a hard sail from Greater Senegambia to southeastern Brazil but an easy sail to the far northeast. Portuguese officials were afraid that newly arrived Africans would be transshipped to the Caribbean from Maranhão because it was an easy sail and prices of slaves in the Caribbean were higher.

10In much of Spanish America during the first two centuries of colonization, Greater Senegambians remained predominant. Geographic proximity, pref erences for “Guineans” (meaning Greater Senegambians), favorable winds and currents, and shorter voyages allowing for smaller ships and crews and fewer supplies were important reasons for this early pattern. Between 1532 and 1580, Greater Senegambians were 78 percent of recorded African ethnicities in Peru and 88 percent in Mexico, with 20.4 percent recorded as Wolof, 18.7 percent as Biafara, and 15.9 percent as Bran.11

Between 1580 and 1640, the crowns of Spain and Portugal were merged but their colonies were administered separately. The papacy had given Portugal a monopoly over the maritime trade along the West African Coast. But the Spanish crown managed to profit handsomely from the slave trade. The asiento licenses sold by the Spanish crown allowed Portuguese merchants to supply African slaves to Spain’s colonies in the Americas. These licenses were sold at high prices and sometimes resold by their purchasers. They represented a significant part of the revenue of the crown of Spain. They were paid in advance, placing all financial risks on the slave traders. The Spanish crown managed to recoup most of the profits made by the transatlantic slave traders to whom they sold these licenses. These asentistas were mainly conversos or New Christians: Jews who had converted to Christianity to avoid expulsion from their Iberian homelands. Many of them had fled from Spain to Portugal, where they were somewhat better tolerated. After most of the New Christian Atlantic slave traders had made their fortunes, they were hauled before the Inquisition in Spanish America; their property was confiscated; and they were tortured and executed: an excellent way for the crown to recoup their profits.

12 The Spanish crown also collected a head tax on every slave arriving from Africa and sold in the Americas. This tax was high: between one-third and one-fourth of the sale price of each slave. All of the goods produced in the Americas and exported to Spain were heavily taxed again: the royal fifth, 20 percent of the price of precious metals; another special tax to cover the costs of protecting the fleets that carried American-produced goods to Spain; the tithe (10 percent) collected by the Roman Catholic Church (whose finances the Spanish crown controlled in the Americas); and sales taxes on all products bought or sold in or exported from Spanish America.

The Portuguese asiento documents are voluminous and well preserved. Enriqueta Vila Vilar established that there was a serious undercount of Africans who were actually brought ashore to avoid paying the head tax on them. Based on her work, Philip D. Curtin acknowledged his serious undercount of the Atlantic slave trade to Spanish America during the first half of the seventeenth century.

13 But the implications of Vila Vilar’s work concerning the numbers of enslaved Africans brought to the Americas as well as the significance of Greater Senegambians among African slaves in the Americas have still not been widely recognized by historians. Greater Senegambia was a major formative African regional culture in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico and surrounding coastal areas as well as along the west coast of South America. This includes the early Spanish Caribbean, especially the island of Santo Domingo and what is now Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. From the earliest years of colonization in the Caribbean, enslaved Africans helped Native Americans revolt against the Spanish colonists. Runaway slaves and runaway slave communities cooperated with pirates and assisted invasions by rival European powers. By the seventeenth century, Spanish American colonial authorities began to lose their taste for Greater Senegambians, especially for the Wolof. They were considered too dangerous and rebellious. Although the import of Wolof into Spanish colonies was repeatedly forbidden, they continued to be brought in in substantial numbers.

14An interesting early example of the prohibition of Wolof by Spanish colonial authorities is a promulgation relating to Puerto Rico (called San Juan Island) issued in 1532 by the Council of the Indies in Spain:

All the destruction caused on San Juan Island and the other islands by the revolt of the blacks and the killing of Christians there were done by the Gelofes living there who by all accounts are arrogant, uncooperative, troublesome and incorrigible. Few receive any punishment and it is invariably they who attempt to rebel and commit every sort of crime, during this revolt and at other times. Those who conduct themselves peacefully, who come from other regions and behave well, they mislead into evil ways, which is displeasing to God, our Lord, and prejudicial to our revenues. This matter having been examined by the members of our Indies Council, and considering the importance for the proper peopling and pacification of these islands that no Gelofe should be moved there, I hereby command you for the future to ensure that no one, absolutely no one, transfers to India, islands and terra firma of the ocean any slave from the Island [sic] of Gelofe without our express permission to that end: any failure in this regard will result in confiscation.

15The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database distorts this period because of misinformation about the meanings of geographic terms defined therein. The voyages listed in the appendix of the Vila Vilar book were entered. But errors involving the meaning of Guinea, the Rivers of Guinea, and the coastal origin of Africans shipped via the Cape Verde Islands, plus the omission of a significant number of voyages coming from these islands, resulted in a serious undercount of Africans brought from Greater Senegambia/Upper Guinea to Spanish America between 1595 and 1640. The database put slaves on voyages coming from Rios de Guinea and Guinea among Africans of unknown coastal origin. Rios de Guinea was not listed as a buying region. Both of these coastal origins with clear meanings during the Portuguese asiento to Spanish America (1595-1640) cannot be disaggregated because there is only one numeric code in the database for voyages of unknown African coastal origin.

Table 4.2. Voyages to Cartagena de Indias with Known African Provenance, 1595-1640

Source: Calculated from Vila Vilar, Hispanoamérica y el comercio de esclavos, appendix, cuadros 3-5.

| Place of Departure | Number | Percentage |

|---|

| Upper Guinea | 55 | 48.2 |

| Angola | 46 | 40.4 |

| São Tomé | 11 | 10.0 |

| Arda (Allada)/Slave Coast | 2 | 1.4 |

| Total | 114 | 100 |

Before enslaved Senegambians were shipped to the Americas, they were often first landed at the Cape Verde Islands. When transatlantic slave trade ships loaded their slave “cargoes” there, they almost invariably originated in Greater Senegambia. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database records only three voyages’ loading their slave “cargo” in the Cape Verde Islands during the Portuguese asiento period (1595-1640). There was then a brisk traffic in slaves to Spanish America from these islands. All seventeen of the other voyages coming from the Cape Verde Islands recorded in this database took place after 1818, when the Atlantic slave trade above the equator was being suppressed by British patrol ships.

Alonso de Sandoval wrote that Portuguese asiento slave trade voyages were coming from only four places in Africa: the Cape Verde Islands, the Rivers of Guinea, the island of Sao Tome, and Luanda, Angola. Sandoval’s information about the African coastal origins of the Portuguese asiento voyages is confirmed by Enriqueta Vila Vilar’s study of the Portuguese asiento documents. The numbers of slaves successfully transported is impossible to calculate. If numbers were recorded, they were substantially underestimated to avoid paying the head tax to the Portuguese crown.

16Trading networks radiated from the Cape Verde Islands to Greater Senegambia. A variety of goods were sold, including salt, which was obtained free in Cape Verde and sold at a high price and/or exchanged for slaves in Greater Senegambia. Cotton, very expensive textiles ( panos), and rum were shipped to several places in the Rios de Guinea region. The result was a substantial sale of enslaved Africans to the Cape Verde Islands, many of whom ended up in the Americas. These complex trading links were extremely profitable and therefore concealed by Portuguese chroniclers, but they were revealed by Dutch reports collecting intelligence about the Portuguese trade in the region.

17

Table 4.3. African Region of Origin of Peruvian Slaves Calculated from Ethnic Descriptions, 1560-1650

Source: Calculated from Bowser, The African Slave in Colonial Peru, 1524-1650, 40-43, tables 1-2.

| Region | All Afro-Peruvians | Bozales |

|---|

| Guinea-Bissau and Senegal | 2,898 | (55.1%) | 1,281 | (55.9%) |

| Other West Africa | 635 | (12.0%) | 248 | (10.8%) |

| West Central Africa | 1,735 | (32. 9%) | 766 | (33. 4%) |

| Total | 5,278 | | 2,295 | |

Many Greater Senegambians arrived in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Cartagena de Indias in Colombia. They were the majority in Peruvian documents between 1560 and 1650 (about 55 percent). West Central Africans were about 33 percent, and many of them were shipped from the Rio de la Plata on the southeast coast of South America via Upper Peru. African ethnicities transshipped from Cartagena de Indias to Peru were mainly from Greater Senegambia. Their origin is very clearly reflected in ethnic descriptions in notarial documents from early Peru.

Africans from the Bights of Benin and Biafra (referred to by Frederick Bowser as “Other West Africa”) did not appear in Peruvian slave lists in significant numbers before 1620. Africans from Lower Guinea were never more than 12 percent among Africans in Peru through 1650. They were fewer among bozales (newly arrived Africans) than among those who had been in Peru longer (12 percent versus 10.8 percent), indicating that clustering of Africans from the two major African regions was increasing rather than diminishing. Greater Senegambians were a substantial majority in Peru despite West Central Africans’ entering Upper Peru from the east coast of Spanish America via the Rio de la Plata (now Argentina and Uruguay); about 1,500 to 3,000 enslaved Africans from Angola were brought in each year during the first half of the seventeenth century. Some of them were transshipped to and remained in Paraguay, Upper Peru (Bolivia), and Chile, but some of them no doubt arrived in Lower Peru as well.

18Although the substantially shorter time required for voyages between Greater Senegambia and the circum-Caribbean was a major factor linking this region with early Spanish America, preference for Greater Senegambians (called Guineans) loomed large. That preference was very clear and significant and continued strong throughout the Portuguese asiento slave trade to Spanish America (1595-1640). Records show that in Cartagena 48.2 percent of voyages came from Upper Guinea and 40.2 percent from Angola —and the ships from Angola normally carried many more enslaved Africans. Thus Greater Senegambians were further clustered during transshipment. Although the numbers game is fruitless because of misrepresentations in these asiento documents, there is no doubt that a substantially higher percentage of Greater Senegambians first taken to Cartagena ended up in Peru. Guineans were highly esteemed, and Peruvians had the silver with which to pay for them. They were so highly valued that their importation to the Americas as slaves was partially subsidized by the Spanish crown. Contracts signed with suppliers of African slaves during the 158os provided that only one-fourth of the sale price of Guinea slaves was to be paid to the crown as a tax, as opposed to one-third of the price of slaves from other regions of Africa. Contracts signed with African slave traders after 1595 required that the greatest possible number of Guinea Africans be supplied. In 1635, an attempt was made to route all Guinean slaves to Spanish America.

19 Africans arriving from Greater Senegambia brought substantially higher prices than Africans arriving from Angola, although this price differential could partially reflect the fact that Angolans arrived in worse condition because of the longer voyages they endured. In 1601, a Portuguese asentista wrote that Guineans (Greater Senegambians) sold for 250 pesos in Spanish American ports, while Angolans sold for 200 pesos. In 1620, Guineans sold for between 270 and 315 pesos, while Angolans sold for 200 pesos.

20Based on his knowledgeable and sophisticated analysis of the African ethnic descriptions collected by Aguirre Beltrán, Frederick Bowser, James Lockhardt, and Colin Palmer, Stephan Buhnen was astounded by the extent of the clustering of African ethnicities in early Spanish America:

For the period 1560-91, we observe the amazing fact that more than half of all African slaves (54.2 per cent) and two-thirds of all Upper Guinean slaves (67.2 per cent) in Peru came from a tiny area of about twenty square kilometers stretching from the lower Casamance (River) to the River Kogon. This was the settlement area of the southern Banol, the Casanga, Folup, Bran, Balanta, Biafara, Bioho, and Nalu. It covers the Western half of Guinea Bissau and a narrow strip of southernmost Senegal.... And within this small area, two ethnic groups supplied staggering numbers: 21.3 per cent of all African slaves in our sample were Bran (n = 282) and 21.4 per cent were Biafara (n = 283).

This region was near the Portuguese slave-trading post of Cacheu. The Bran were cultivators of wet rice produced in reclaimed mangrove swamps. Their population density allowed them to withstand the impact of the Atlantic slave trade to a greater extent than could many other African peoples.

21Sandoval explained in great detail why Spanish officials and colonists in the Americas prized Senegambians (whom he referred to as Guineans) above Africans from any other region. He praised their intelligence, strength, resiliency, temperament, and musicality:

These Guineans are the blacks who are most esteemed by the Spanish; those who work the hardest, who are the most expensive, and whom we commonly call of law. They are good natured, of sharp intelligence, handsome, and well disposed; happy by temperament, and very joyous, without losing any occasion to play musical instruments, sing, and dance, even while they perform the hardest work in the world ... without fatigue, by night or by day with great exaltation, shouting in an extraordinary way and playing such sonorous instruments that their voices are sometimes drowned out. One admires how they have the heart to shout so much and the strength to jump. Some of them use guitars similar to ours in their style. There are many good musicians among them.

Catholic missionaries took due note of the mechanical and metallurgy skills of Senegambians. But they mistakenly assumed they had learned these skills from Spanish Gypsies: “From the communication they have had in the ports with the Spanish, they have learned many mechanical skills. Mainly, there are a large number of blacksmiths using the techniques of the Gypsies of Spain. They make all the arms which we ask them for and whatever curiosities we desire.”

Sandoval described a process of transculturation among Guineans and Iberians: “It is these Guineans who are closest to the Spanish in law and who serve them best. The ways of the Spanish please them, even though they are gentiles. It is important to them to learn our language. They delight in dressing themselves festively in the Spanish way with our clothing which we have given them or which they have bought. They praise and extol our holy Law and feel that their own is bad. Virtue is such a beautiful thing that even these people love it to the extent that they have many Spaniards in their lands and much clothing and other things from Europe in their houses.”

But the acculturation process went both ways. “Many Spaniards and other Christians of various nations live with them voluntarily in the interior of their land and do not wish to leave them because of the broad freedom of conscience they enjoy there. They die not only without God, but without worldly goods for which they have worked so hard because the king of the land inherits all of it when they die.”

22Sandoval was no doubt referring to the

lançados, many of whom were New Christians (conversos). The Portuguese chronicler Alvares de Almada described one of the most remarkable of them: a man named João Ferreira, a Jewish native of Crato, Portugal, who was called Ganagoga by the blacks. In the Biafara language, “Ganagoga” means “one who speaks all languages.” Ganagoga made a living by selling ivory down the Senegal River. He was reported to be actively trading in ivory in 1591. Ganagoga married a daughter of the Grand Fulo (Fulani), had a daughter by her, and became a powerful political figure.

23After Portugal separated from Spain in 1640, Spanish slave traders dominated at Cacheu in Greater Senegambia. Their undocumented voyages paid no taxes to Portugal. We only know about them because they appear in documents in the form of unsuccessful Portuguese efforts to repress them.

24By the mid-seventeenth century, Africans and their descendants in the Caribbean began to outnumber whites very substantially. This demographic imbalance escalated during the eighteenth century. Because of their reputation as rebels, Greater Senegambians became less welcome. Although Greater Senegambians were feared in Spanish colonies, they were readily accepted—if not preferred—in the colonies eventually incorporated into the United States, where black/white ratios were much more manageable and therefore security problems did not loom as large. The Greater Senegambians’ skills were especially needed in rice and indigo production and in the cattle industries of Carolina, Georgia, the Florida panhandle, and Louisiana. During the eighteenth century, Greater Senegambians were more clustered in colonies that became part of the United States than anywhere else in the Americas. These colonial regions include the Carolinas, Georgia, Louisiana, the lower Mississippi Valley, and the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico extending across Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, the Florida panhandle, and, to a lesser extent, Maryland and Virginia. The Stono Rebellion of 1739 has focused attention on West Central Africa as a source for enslaved Africans brought to South Carolina. But a majority of Atlantic slave trade voyages arrived in South Carolina from West Central Africa during only one decade : between 1730 and 1739. The Stono Rebellion of 1739, well described as a Kongo revolt, evidently discouraged South Carolina planters from bringing in more West Central Africans. Thereafter, Greater Senegambia became

Phillis Wheatley, circa 1773, around age twenty. She was from Gambia and most likely a Mandingo. (Phillis Wheatley, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, 1773.)

the major source of Atlantic slave trade voyages for the rest of the eighteenth century. But the number of slaves on voyages arriving from Greater Senegambia was substantially smaller than on voyages arriving from other African regions. West Central Africa did not become a significant source of Africans for South Carolina again until 1801: only six years before the foreign slave trade to the United States was outlawed on January 1, 18o8. From the study of transatlantic slave trade voyages, it appears that during the eighteenth century the United States was the most important place where Greater Senegambians were clustered after the northern European powers legally entered the Atlantic slave trade. Studies of transatlantic slave trade voyages to the United States are reasonably revealing about trends in ethnic composition because there was no large-scale, maritime transshipment trade to colonies of other nations. This conclusion must be qualified because of the unknown, and probably unknowable, extent and ethnic composition of new Africans transshipped from the Caribbean to the east coast ports of the United States. But it is likely that Greater Senegambians were quite significant in this traffic because of selectivity in the transshipment trade from the Caribbean. From the point of view of African ethnicities arriving in South Carolina, the artificial separation between Senegambia and Sierra Leone obscures the picture. Thus the role of Greater Senegambians was very important in South Carolina. There is evidence that Senegambians were clustered regionally in the Chesapeake and probably elsewhere as well, especially on the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina and other rice-growing areas of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

25 The patterns for Louisiana are clear and not at all speculative. Greater Senegambians loomed large among Africans there. In the French slave trade to Louisiana, 64.3 percent of the Africans arriving on clearly documented French Atlantic slave trade voyages came from Senegambia narrowly defined. Based on The

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database for British voyages to the entire northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico as well as additional Atlantic slave trade voyages found in Louisiana documents that were included in the Louisiana Slave Database but not in The TransAtlantic Slave Trade Database, this writer’s studies show that slave trade voyages coming from Senegambia were 59.7 percent of all documented voyages coming directly from Africa to Louisiana and the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico between 1770 and 1803. Nevertheless, the African coastal origin of Louisiana slaves during the Spanish period was much more varied than Atlantic slave trade voyages indicate. The vast majority of new Africans arriving in Spanish Louisiana were transshipped from the Caribbean, especially from Jamaica, where Gold Coast Africans were preferred and retained.

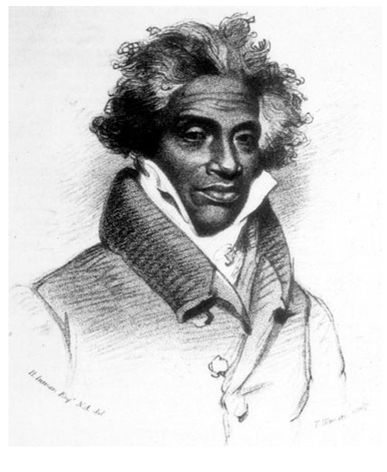

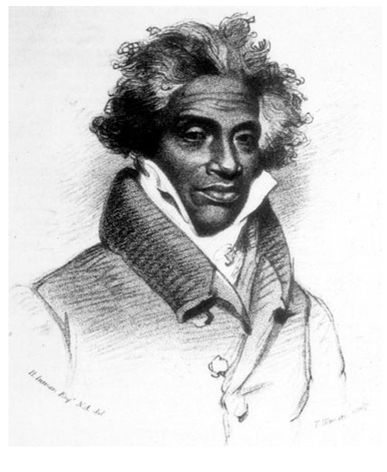

Job Ben Solomon, an educated Fulbe Muslim who was sold into slavery around the age of twenty-nine. (Rare Books and Special Collections, Library of Congress. From the website “The Atlantic Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Americas: A Visual Record,” <http://hitchcock.itc.virginia.edu/Slavery>.)

Abdul Rahaman, born in Timbuktu around 1762, an educated Fulbe Muslim who was sold into slavery at about the age of twenty-six. Engraving of a crayon drawing by Henry Inman, 1828. (The Colonizationist and Journal of Freedom, 1834. From the website “The Atlantic Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Americas: A Visual Record,” <http://hitchcock.itc.virginia.edu/Slavery>.)

In Louisiana, if we exclude Atlantic slave trade voyages and study only descriptions of slaves in internal documents, Africans from “Senegambia” were 30.3 percent and those from “Sierra Leone” were 20.8 percent, or a total of 51.1 percent from Greater Senegambia. If we exclude slaves described as being from “Guinea” or the “Coast of Guinea” from the Sierra Leone category, Africans from Sierra Leone drop to 6.7 percent. The result is a minimum of 37 percent of Africans of identified ethnicities from Greater Senegambia in Spanish Louisiana. As we have seen in our discussion of the meanings of “Guinea,” there are cogent reasons for tilting toward the higher figure.

In the two major rice-growing states of the Anglo-United States, 44.4 percent of Atlantic slave trade voyages arriving in South Carolina and 62.0 percent arriving in Georgia listed in The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database brought Africans from Greater Senegambia. These gross, static figures are impressive enough. But when we break down calculations for Anglo-United States colonies and states over time and place, we see a wave pattern clustering Africans from Greater Senegambia. In South Carolina, 50.4 percent of all Atlantic slave trade voyages to that colony entered into The Trans-Atlantic, Slave Trade Database arrived between 1751 and 1775, with 100 (35.2 percent) coming from Senegambia and 58 (20.4 percent) coming from Sierra Leone: a total of 55.6 percent coming from Greater Senegambia. As we have seen, both Mandingo and Fulbe were being exported from both of these regions. During this time period, Britain had occupied the French slave-trading posts along the coast of Senegambia. Close to half (44.7 percent) of the British Atlantic slave trade voyages from Senegambia (narrowly defined: excluding Sierra Leone) went to Britain’s North American mainland colonies. Five out of six Atlantic slave trade voyages to British West Florida ports along the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico came from Senegambia narrowly defined. It is safe to say that between 1751 and 1775, the majority of slaves loaded aboard British ships leaving from Senegambia were sent to regions that would become part of the United States. As Yankee traders and Euro-African suppliers took over the Atlantic slave trade on these coasts during the Age of Revolutions, voyages bringing Africans to the United States from Greater Senegambia originated mainly in various ports on the American side, were heavily involved in smuggling and piracy, were never documented in European archives, and were unlikely to be included in The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. There is little doubt that most of these voyages brought Greater Senegambians to the United States and to the British Caribbean.

Figure 4.1. Atlantic Slave Trade Voyages to South Carolina (1701-1807). Calculated from Eltis et al., The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. Voyages from “Windward Coast” added to Sierra Leone.

Although the Igbo from the Bight of Biafra loomed large in the Chesapeake, Greater Senegambia was a formative culture in some regions of the Chesapeake as well. Lorena Walsh has noted that nearly half of the voyages bringing about 5,000 Africans to Virginia between 1683 and 1721 came from Senegambia narrowly defined. There was a clustering of Atlantic slave trade voyages from the same African coasts to regional ports in the Chesapeake.

26In sum, The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database is probably less useful for Greater Senegambia than for any other African region except perhaps for West Central Africa. While it undercounts the massive Portuguese and Brazilian slave trade voyages coming mainly from Angola, it undercounts voyages coming from Greater Senegambia as well. (The creators of the database, David Eltis, David Richardson, and their associates, are supporting research to correct its deficit in Portuguese and Brazilian voyages. This very difficult task is in the good hands of Manolo Garcia Florentino.) Thus there are a comparatively small number of transatlantic slave trade voyages from Greater Senegambia because in many instances the point of origin was improperly entered. As we have noted before, the database defines the African coast recorded in documents as “Guinea” or the “Rivers of Guinea” as an unknown African coastal origin, writing the mistake into cybernetic stone. These voyages are lumped indistinguishably with unidentified African coasts and cannot be disaggregated for calculations. Propinquity and favorable winds and currents in the North Atlantic system linked Greater Senegambia and the North American continent and continued to dominate maritime trade until the invention and wide adoption of steam engines in ships at sea at the end of the nineteenth century. Shorter voyages allowed for the use of smaller ships requiring fewer supplies and crew members. Rebellions aboard slave trade ships, an extremely serious problem for voyages coming from Greater Senegambia, were less frequent on small ships.

Many of the two-way voyages between North America and Africa were undocumented. Documents for other voyages are probably scattered among surviving documents in ports throughout the Americas. We have seen that there is evidence for ongoing, direct trade involving American slave owners/ traders/ship owners, often-overlapping categories, and Euro-African merchants in Greater Senegambia. These small voyages were probably numerous and undocumented. Enslaved Africans were purchased directly by slave owners for their own use rather than for resale in the Americas. These slaves therefore do not show up in European or American sources, either in lists of incoming ships, advertisements for the sale of newly arriving slaves, or documents involving sale of slaves. The large, centralized European archives documenting large, commercial voyages are very unlikely to contain documents involving privately organized voyages initiated in the Americas. Before the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, Afro-Portuguese and Yankee traders and smugglers had taken over the slave trade along the coast south of the Gambia River. Jean Gabriel Pelletan, director of the French Company of Senegal in 1787-88, wrote that French slave trade ships rarely stopped between the Gambia and the Sierra Leone rivers because Afro-Portuguese drove their rivals away by force.

27 After the French Revolution began in 1789, these invisible voyages from Greater Senegambia increased sharply. By 1794, Yankee traders had seized control of the maritime slave trade from the French and set up trading stations, although a few voyages were organized by French slave traders under neutral flags.

28 After 1808, when Britain outlawed the Atlantic slave trade, British anti-slave trade patrols began operating along the West Coast of Africa above the equator. Warfare among the major European powers brought the open, large-scale, commercial Atlantic slave trade in Greater Senegambia to a halt. Nevertheless, we find large numbers of young Greater Senegambians listed in American documents during the first few decades of the nineteenth century.

B. W. Higman’s detailed, sophisticated study of the slave population of the British West Indies established the importance of Senegambia as a source of slaves during the nineteenth century. From Higman’s point of view, the slave trade from Senegambia alone, not including Sierra Leone, “remains grossly underestimated.” Writing in 1984, he noted that Roger Ansty recorded a mere 0.7 percent of British slave voyages from Senegambia during the 18oos. The

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database reveals 1.9 percent. But data concerning the five British West Indies colonies where African ethnicities of slaves were listed in pre-emancipation documents show that between 1817 and 1827 Africans from Senegambia narrowly defined ranged between 10.1 percent and 43.4 percent. Higman’s coastal designations were derived from African ethnicity descriptions in American documents, not from documented Atlantic slave trade voyages. These largely complete lists are convincing evidence that there were many more Greater Senegambians brought to the Americas than studies that confine themselves to documented Atlantic slave trade voyages reveal.

29

THIS CHAPTER WILL CONCLUDE with a discussion of the Bamana, a designation incorrectly spelled and pronounced “Bambara.” They were a self-conscious ethnic group exported from Greater Senegambian ports, mainly Gorée and along the Gambia River. Europeans in Africa had broad and sometimes vague definitions of the “Bambara.” For example, they designated all slave soldiers as “Bambara.” Names, including ethnic names, are a sensitive matter in Africa. During my lecture tour of Francophone Africa in 1987, I was told emphatically and indignantly that I should use the ethnic designation “Bamana,” not “Bambara.” David Hackett Fischer had a similar experience during his trip to Mali. I continued to use the spelling “Bambara” because it is universal in European languages. But I now use “Bamana” because “Bambara” is more than inaccurate. It is a sarcastic insult created by Muslim Africans : a neologism that twists this ethnic name to mean “barbarian” (barbar in Arabic).

30The meaning and identity of “Bambara” must be discussed within the context of changes taking place on both sides of the Atlantic. The French transatlantic slave trade to Louisiana took place almost entirely during the early stages of the formation of the Segu Bamana Kingdom, when small Bamana polities were raiding each other to produce slaves who were then shipped down the Senegal River and sold into the Atlantic slave trade by the Mandingo. According to Philip D. Curtin,

The “Bambara” slaves shipped west as a result of eighteenth-century warfare or political consolidation could be dissident people who were ethnically Bambara, or they could just as well be non-Bambara victims of Bambara raiders. In any event, the first flow of “Bambara” appears to have come from the northern part of the Bambara region, being transshipped by way of Jara on the Sahel. Then, from the

172os, the flow was more clearly from the Bambara core area, and jahaanke were the principal carriers. This new source of Bambara slaves after about 1715 seems to be associated with the rise of Mamari Kulibali (r. 1712-55) and his foundation of the kingdom of Segu [emphasis added] .

31The documented French Atlantic slave trade to Louisiana took place entirely between 1718 and 1731 except for one voyage arriving from Senegambia in 1743. Two-thirds of the Africans arriving on French-period Atlantic slave voyages arrived from Senegal narrowly defined. These are unusually well documented voyages. Because of ignorance of the geographic location of ports of arrival, incorrect information about the French Atlantic slave trade to Louisiana was published in a widely cited article based on calculations from a prepublication version of The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database that undercounted voyages from Senegambia to French Louisiana.

32 The published version of the database corrected these omissions from the French period but omitted three clearly documented Atlantic slave trade voyages arriving during the Spanish period in 1803 because of limitations in its search engine or because they could not be found in the Lloyd’s List of Atlantic Slave Trade Voyages. Two of these voyages also came from Senegambia narrowly defined.

33In my book Africans in Colonial Louisiana, based on the number of “Bambara” reportedly involved in the Samba Bambara conspiracy in 1731 and the total number of slaves reported in the 1731-32 censuses, I estimated that about 15 percent of the slaves in Louisiana were Bamana (“Bambara”) at the time of the conspiracy. They were far from a majority during the French period, and much less during the Spanish period, although they were clearly overrepresented among those accused of “crimes,” including running away, conspiring, and revolting against the French regime.

34 In my discussion of whether the “Bambara” in Louisiana were truly “Bambara” or not, I made a clear distinction between the French period (1719-69) and the Spanish period (1770- 1803). Discussing the Spanish period, I concluded with “The Bambara, if such they were ...”

By the last half of the eighteenth century, the meaning of “Bambara” to Europeans in Africa had broadened substantially. Warriors were at various stages of incorporation into the Bamana language and culture as they were captured in warfare expanding beyond the Bamana core areas. In 1789, Lamiral wrote:

Of 50 slaves who arrived [in St. Louis from the interior of the continent] , there are 20 nations of different customs and language who do not understand each other. Their faces and bodies are scarred differently. These blacks are designated in Senegal by the generic name of Bambara. I have questioned many of them about their country, but they are so stupid that it is almost impossible to obtain a clear notion. One can be tempted to believe that they are taken there in flocks and that they are brought without their knowing where they come from or where they are going. Nothing bothers them, and as long as they are allowed to eat their fill, they will follow their masters to the Antipodes. Their only fear when they are embarked is that they will be eaten by the whites.

35Regardless of what “Bambara” meant to Europeans in Africa, it had a clear meaning among slaves in Louisiana. The Bamana in Louisiana knew who they were. In 1764, a group of slaves and runaway slaves were arrested in New Orleans and interrogated. Their leader was Louis dit Foy, one of the uncontrollable slaves who were bounced around the British mainland colonies, the Caribbean, the Illinois country, and South Louisiana. When he was sworn in, he testified that though he was named Louis by the French, his real name was Foy in the language of his country, which he identified as the Bambara nation. The witnesses who testified about Foy, whites as well as blacks, referred to him as Foy, his Bamara (Bambara) name. Andiguy, commandeur of Madame de Mandeville, identified himself as a Bambara and testified that he knew Foy because he was his fellow countryman.

Foy had organized a cooperative network among slaves, runaways, thieves, seamstresses, and street vendors who manufactured and sold clothing, food, and other goods. They held regular social gatherings, including feasts in New Orleans in a cabin in the garden of one of their masters.

Testimony was taken from the accused as well as from other persons, white and black, slave and free. As recorded by the notary, these African slaves expressed themselves fully and eloquently in French, with a few creolisms thrown in. No interpreters were used. Their testimony reveals a network of mainly Mande language group speakers belonging to several different masters in and around New Orleans. When the Africans were asked how they knew each other, they often replied that they were from the same country, which was considered enough of an explanation by their interrogators. They stole a considerable quantity of food, some of which they cooked and ate at their feasts and then sold the rest. Foy, Cesar, a Creole runaway slave, and another slave killed a pig they found on the deserted Jesuit plantation. The pig was so fat that they had to cut it in half to get it over the city wall. Foy sold some of his share of the pig to the slaves of Brazilier living along Bayou St. Jean. He complained that they never paid him, which is why he finally informed on them. He and Cesar gave the rest of the pig to his companions in Cantrell’s garden, keeping them in meat for some time.

Comba and Louison, both Mandingo women in their fifties, were vendors selling cakes and other goods along the streets of New Orleans. They maintained an active social life, organized feasts where they ate and drank very well, cooked gumbo file and rice, roasted turkeys and chickens, barbecued pigs and fish, smoked tobacco, and drank rum. Comba testified from prison. She said her name was Julie dit Comba, her Mandingo name. Other slaves who testified referred to her as Mama Comba. Cantrell’s slave Louison also identified herself as a Mandingo. She lived in a cabin in her master Cantrell’s garden where they held their feasts. She testified that her close friend Comba, known by the French as Julie, was also a Mandingo. Comba described Louison as sa paize (fellow countrywoman). The group included several other male “Bambara” slaves. According to Mama Comba, these “Bambara” men amused themselves very much.

Foy was clearly the brains of the group. A true entrepreneur, he organized and masterminded their economy. It involved the manufacture of garments and the distribution and sale of various stolen items including clothes, jewelry, wood, and food, especially chickens and turkeys because they were hard to trace. He employed slave seamstresses to make the garments, mainly shirts and pants, from cloth he bought or stole. And in fact, according to Mama Comba, Foy boldly used cloth he had stolen to sew garments while sitting at the entrance to the poorhouse where she worked. He employed other slaves to sell his wares, women as well as men, including fellow Bamana belonging to several different masters. Foy was too careful a thief to steal cattle because it could be traced and identified by the hides. He dealt in small objects that were hard to trace and could be easily concealed. He and his sales-people avoided barter, operating with cash, sometimes large amounts of cash, to minimize the risk of being caught with stolen goods.

In this Mande language-group community, the women were mainly Mandingo and the men Bamana, reflecting the very high proportion of males among enslaved Bamana. They maintained their ethnic distinctions although they spoke mutually intelligible dialects of the Mande language as well as French with traces of Louisiana Creole or possibly Louisiana Creole recorded in the documents as French. They identified their own and each others’ ethnicities. They shared a long history and closely related culture in Senegambia, their place of origin in Africa. Their gender composition is understandable. The Bamana were mainly war captives brought some distance from the interior, and there were very few women among them. The Mandingo were Muslim, while the Bamana maintained their traditional religion. Mandingo traders were active buying Bamana captives and transporting them to the Atlantic coast for sale into the Atlantic slave trade, but the Mandingo eventually got caught up in the slave trade and were shipped in growing numbers to the Americas as the eighteenth century advanced. Ethnic conflicts in Africa were no doubt forgotten among these kidnapped and enslaved folks in a foreign land where they were happy to find and be able to communicate in their native language with other Africans from their homeland.

36In 1799, two adult male slaves were sold into Avoyelles Parish by the slave trader Peytavin Duriblond. It was noted in the sale document: “Qui se disent leur nation Bambara [They say their nation is Bambara].”

37 These Africans identified themselves as Bamana at this particular time and place. I can only accept their self-identification. It is quite possible that some of them arrived during the last half of the eighteenth century and had not always been Bamana. Some of them may have been captives incorporated into the expanding armies of Segu and at least partially socialized into the Bamana language and culture. But if we do not take their word for it that they were indeed Bamana, we will have to assume that ethnicity is genetically based and therefore unchangeable.