CHAPTER ONE

BRITISH GUIANA 1831-1953

British Guiana/Guyana’s modern political history began in April 1953, when the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) led by Cheddi Jagan and Forbes Burnham achieved an overwhelming victory in the colony’s first national election. The PPP’s triumph seemingly heralded the beginning of British Guiana’s evolution into an independent nation with a multiracial, parliamentary democracy. Within five months after the election, however, imperial Great Britain, citing fears of communism, sent troops to British Guiana and suspended the new constitution. The tumultuous events of 1953 would force the United States to consider what it envisioned for British Guiana, a foreign colony within its traditional Western Hemisphere sphere of influence. Over the next two decades, U.S. policies would bear out Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s smug prediction that, when it came to British Guiana, their “anti-Colonialism will be more than balanced by their anti-Communism.”1

NEITHER GEOGRAPHY NOR HISTORY has been especially kind to the people of Guyana. Guyana is part of the general region of the Guiana Highlands on the northeastern coast of South America, bounded by the Amazon, Negro, and Orinoco rivers. The Guianas today include the nations of Guyana, Surinam, a former Dutch colony, and French Guiana. The Guianas all border Brazil, with Guyana sharing to its west a disputed border with Venezuela. The visual beauty of the region is spectacular, serving as locale for romantic fables, including Sir Walter Raleigh’s mythic El Dorado and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Lost World. England’s great poets, William Shakespeare and John Milton, refer to Guiana’s “good and bounty” and its “unspoiled” nature. Making a living in this fabled land has proved, however, challenging.

The word “Guiana” is a word of Amerindian origin, signifying “land of many waters.” Three major rivers, the Essequibo, Demerara, and Berbice, drain Guyana, originating in a system of mountain ranges in the interior and descending northward into the Atlantic Ocean. The rivers flow through largely uninhabitable land. More than 80 percent of Guyana is tropical rain forest. The rain forests do produce some commercially valuable trees, but the timber industry has never been a leading sector of Guyana’s economy. Prospectors have not found significant quantities of precious minerals, like gold and diamonds, in the forested mountains. Two other interior regions—the savanna and the hilly sand and clay belt—also provide poor prospects for agricultural development. For cattle ranching, for example, one animal requires approximately seventy acres of savanna for grazing. The three regions comprise 96 percent of Guyana’s territory.

Guyana’s human history has played out along Guyana’s fertile coastal plain, which stretches along the Atlantic shoreline and varies in depth from ten to forty miles. The rich land is capable of producing cash crops like coffee, cotton, rice, and sugar. Heavy rain and high humidity make the region’s climate difficult but tolerable. The major city, Georgetown, situated at the mouth of the Demerara River, has a mean temperature of 80 degrees Fahrenheit, but with cooling sea breezes at night. Tidal flooding and river flooding caused by torrential downpours bar easy cultivation of Guyana’s coastal plain. For a depth of five to eight miles, the coastal plain is below sea level at high tide. Guyanese have had to construct and constantly maintain an intricate network of seawalls and dikes to hold back the sea and canals, dams, and sluices to improve drainage and pump water back into the Atlantic at low tide. A typical sugar plantation would have 250 miles of waterways for irrigation and transport of sugar cane and 80 miles of drainage canals. Agricultural production in the coastal plain has consequently required abundant sources of labor and constant work.

2The first European explorers found the Guianas thinly settled by Amerindian people, who lacked the great wealth and resources of urban societies like those of the Aztecs and Incas. The Amerindians either succumbed to European diseases or fled to the interior, resisting European attempts to enslave them; by the mid-twentieth century, Amerindians comprised only about 4 percent of Guyana’s population. The Dutch became the first permanent European occupier of Guyana. Under the aegis of the West India Company of the Netherlands, they founded a colony on the Berbice River in 1620s. They subsequently established the colonies of Essequibo and Demerara. Until the mid-eighteenth century, the three colonies were small and economically insignificant. In 1701, only sixty-seven Europeans resided in the Essequibo colony. But in the mid-eighteenth century, the governor general of the West India Company opened the colonies to British settlement, and the colonies, especially Demerara and Essequibo, began to grow and prosper. British planters migrated from agriculturally depleted, overpopulated areas such as Barbados. Settlers also gradually mastered the techniques of draining the coastal plain.

3During the period between the Seven Years’ War (1756-63) and the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815), Europeans fought among themselves for control of the South American continent and domination of the world. The colony of Demerara changed colonial hands a bewildering six times during this period. Despite its loss of its thirteen North American colonies, Great Britain emerged triumphant in this global struggle. In 1803 Great Britain assumed effective control over the Dutch colonies and in 1814-15, at the Congress of Vienna, the Dutch formally ceded Berbice, Demerara, and Essequibo to the British. In 1831, the imperial British united the colonies to form the colony of British Guiana, with Georgetown as its administrative center. Georgetown had previously carried the Dutch name of Stabroek. The British ruled British Guiana until 1966, when the colony secured its independence and took the name of Guyana.

Although the colonial masters of the region changed hands, the socioeconomic structure of colonial life—plantation agriculture based on imported coerced labor—remained constant. On the river banks and coastal plain, Dutch planters oversaw the cultivation of coffee, cotton, and especially sugar for sale on the international market. Slaves stolen from Africa nurtured these cash crops. Africans quickly became the largest group in the three Dutch colonies. Although only 67 Europeans resided in Essequibo in 1701, thirty of them owned 800 slaves. Slavery grew rapidly from the mid-eighteenth century on, when British planters from the West Indian islands migrated to the Dutch colonies and quickly came to dominate plantation life. By 1800 perhaps 100,000 slaves toiled in the three colonies. By 1820, about 80,000 people lived in Demerara and Essequibo, with 75,000 of them being slaves. The other 5,000 consisted of approximately 2,500 whites and 2,500 free blacks. Some plantations became like giant factories with over 300 slaves harvesting the sugarcane and processing it in the sugar mills. Slavery lasted until 1838 in British Guiana. In 1807, the House of Commons made it illegal for any British ship to be involved in the international slave trade after 1 January 1808. British legislators followed this with a gradual, compensated emancipation law in 1834. In 1838, approximately 85,000 slaves gained their freedom in British Guiana.

4Twentieth-century Afro-Guyanese had the right to bitter historical memories of the viciousness and cruelty that their ancestors endured under slavery and the disappointments and injustices they experienced after emancipation. Sugar planters customarily worked slaves to death and, before 1808, imported new ones. Slaves were supposed to work twelve hours a day but their work days often stretched over twenty hours. Pregnant women and nursing mothers often did not receive the reduced work loads that the slave codes promised. In 1824, a British doctor reported that twenty-nine of the sixty-seven children born on one estate died within two years. Disease, inadequate medical care, overwork, unhealthy working conditions, and poor diet all contributed to high slave mortality rates. Between 1808 and 1821 in Demerara, the slave population declined by almost 20 percent. Little wonder that slaves resisted their oppression in every conceivable way from physical aggression to insubordination. In 1828, colonial officers recorded over 20,000 “Offences Committed by Slaves.” A dramatic challenge came in 1823 when perhaps 12,000 slaves in Demerara rebelled in one of the most massive slave rebellions in the history of the Western Hemisphere. British troops forcibly suppressed the rebellion, killing over 200 slaves and executing many others thereafter following summary trials. British authorities placed the heads of the executed on poles, hoping to terrorize the slaves.

5Emancipation brought neither progress nor prosperity to British Guiana’s oppressed black majority. Slave owners received an average rate of fifty-one pounds sterling per slave or a total of over £4 million in compensation for losing control over 85,000 people. But as one historian of nineteenth-century British Guiana ironically remarked, “It occurred to no one to compensate the slaves for their previous bondage.”

6 Freed people also had no opportunity to exercise their numbers to bring about meaningful change in the colony. Voting rights were tied to high property requirements, ensuring continued planter control under British rule through the nineteenth century. Despite their poverty and powerlessness, former slaves made heroic efforts to improve their lives. Groups bought abandoned sugar plantations and tried establishing rural cooperative ventures. These enterprises failed because of a lack of capital and the unending difficulty and cost in British Guiana of draining the land. Blacks further thought that they might bargain collectively with planters at the critical harvesting times for the sugar cane. Planters successfully resisted these efforts by finding alternative labor sources. In any case, many blacks associated plantation labor with their former degradation. They drifted toward the coastal towns and especially toward Georgetown, becoming wage laborers. As the colonial bureaucracy grew, a few blacks gained lower-level civil service positions and entered the lower ranks of the police force. In the twentieth-century, the blacks of British Guiana also became miners and workers in the bauxite industry. Former slaves, many of whom were born in Africa, and their descendants gradually became acculturated to British colonial life, learning English and converting to Protestant Christianity. They also gradually gained literacy. In the mid-nineteenth century, the colonial government began to support financially a system of schools owned and operated by Christian churches.

7The end of slavery did not abolish British Guiana’s system of plantation agriculture based on imported coerced labor. Colonial authorities and planters responded to the end of slavery and demands by freed people for good wages by returning to a labor system used in the seventeenth century in the North American colonies—indentured servitude. Antislavery groups in Britain actually encouraged the practice, believing the resuscitation of plantation agriculture in the British West Indies and British Guiana would demonstrate to slaveholders in the United States that they need not fear abolition. British authorities were also meeting imperial labor demands, shifting impoverished people from one part of the empire to another. In the period from 1838 to 1860, Portuguese from the Madeira Islands and Chinese from Hong Kong were the predominant groups to arrive as indentured servants in British Guiana. Both groups, about 25,000 people in total, detested plantation work and either returned home or moved to villages and towns after completing their contracts. Portuguese and Chinese came to dominate British Guiana’s retail trade, becoming shopkeepers, peddlers, and merchants. Colonial India, however, provided the bulk of British Guiana’s new labor force. Between 1838 and 1917, when indentured servitude was abolished in the empire, approximately 240,000 “East Indians” arrived in British Guiana as indentured servants.

8 (British colonial authorities used the misleading term “East Indians” to characterize their colonial subjects in India and to distinguish them from their subjects in the Caribbean, the “West Indians”.) With this influx of Portuguese, Chinese, and Indians, combined with Amerindians, blacks, and English, British Guiana became in the nineteenth century one of the most ethnically, racially, and religiously diverse places in the Western Hemisphere.

The hungry and poor Indians who were persuaded to risk their lives in British Guiana generally belonged to lower agricultural and laboring castes, and a few were outcastes or “pariahs.” The vast majority were illiterate. Most Indians were Hindus but a substantial proportion, perhaps 18 percent, were Muslims. India insisted that at least 25 percent of the recruits be female. Most Indians came from Bengal, Bihar, and the Northwest Provinces, agricultural regions located in contemporary India. These regions experienced periodic famines in the nineteenth century. The indentured servants embarked from the ports of Calcutta and Madras. The voyage to British Guiana lasted about ninety days, with ships going around the Cape of Good Hope. Voyagers were subjected to cold, poor diet, and seasickness. Mortality rates on the overcrowded ships averaged 2 percent for each month aboard in the 1860s and could soar if a catastrophic disease broke out.

9 Helpless Indians got a taste of what West Africans had suffered during the infamous “middle passage.”

Upon arriving in British Guiana, Indians entered what contemporary observers denounced as “slavery.” The immigrants signed a five-year contract to work on sugar plantations, but actually had to serve ten years in order to win passage back to India. Colonial ordinances mandated seemingly reasonable work and living conditions for indentured servants. Planters, with the silent acquiescence of most colonial officers, ignored those ordinances. British Guiana’s survival depended on the sale of sugar in a globally competitive market. As a British governor reported to London in 1871, sugar was “the one great staple export, upon the prosperity of which the general welfare of the Colony may be said almost wholly to depend.”

10 After the mid- 1850s, Great Britain, which was embracing free trade principles, no longer granted a preference to sugar from its West Indian colonies. British Guiana’s sugar also competed with Brazilian and Cuban sugar produced by slave labor. These economic imperatives, when fused with racism and planter control, made, in one historian’s view, “for an oppressive society which allowed no serious opposition.”

11Indian workers, referred to as “coolies” by planters and colonial officers, lived in the former slave quarters, dubbed “nigger yards.” They worked endlessly, cultivating the fields, maintaining drainage systems, and boiling the sugarcane. They had to meet roll call every morning at 6:00 A.M., and they needed a pass to leave the plantation. Mortality rates were ghastly, averaging 4-6 percent a year, with some plantations having a 10 percent mortality rate. In 1863, for example, 1,718 indentured servants out of 32,001 died in the colony. Indians were also subjected to legal abuse. In 1872, 9,045 out of 38,918 indentured immigrants on plantations, a full 23 percent, were charged with breaching their contracts.

12 They stood no chance in the colonial judicial system, for, as one appalled colonial magistrate charged in a report to the Colonial Office in late 1869, “the manager can always produce a number of overseers, drivers, and others dependent upon him to make an overwhelming weight of testimony in his favor.” Without legal protections, the immigrants “are thus often reduced to a position which in some respects is not far removed from slavery.”

13 Such dispatches prompted London to send an inquiry commission in 1870 to investigate life in British Guiana. The commissioners confirmed the horror that was life on a sugar plantation in British Guiana, but the Colonial Office predictably ended up supporting the planters.

As had the black slaves of British Guiana, Indians resisted their abusers, frequently rioting on the plantations. But most servants concentrated on living and building a community. Of Indians who survived indenture, perhaps two out of three stayed in British Guiana. They recreated Indian village life, with a strong emphasis on family life, and celebrated their religion, building temples and mosques. Groups of immigrants combined their meager earnings to buy a cow to be shared by the group. Hindus and Moslems lived peacefully together. Indians also gradually submerged the communal and caste differences of Mother India. Most Indians continued working on sugar plantations, often as wage laborers. Some Indians purchased tracts of British Guiana’s inexpensive wetland and remarkably became independent rice farmers, creating a small property-owning class. Rice production did not require the massive capital investments associated with sugar production. By the early twentieth century, British Guiana began to export rice. Indian life remained largely rural, and most Indians lacked literacy skills. Colonial authorities declined to fund schools operated by non-Christians. Indians were reluctant to send their children to Georgetown for education in Christian denominational schools. As Joseph A. Luckhoo, an Indian barrister whose family had converted to Christianity, noted in 1919, for an Indian “to send his boy to a denominational school to be taught English is to denationalize him and jeopardize his religious faith, and so the Indian maintains a calm indifference towards it.”

14 As British Guiana moved into the twentieth century, the colony’s largest groups—the peoples of West Africa and India and their descendants—remained physically and culturally separated.

Whereas sugar remained the basis of British Guiana’s political economy, significant change rocked the industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The planters prospered in the 1870s as British Guiana, along with Trinidad, became leading producers of sugar in the empire. In the 1880s, however, cane producers faced tough competition in the British market from beet sugar produced in Germany. British Guiana’s sugar also lost its place in the U.S. market. After the United States occupied Cuba in 1898, it negotiated the Reciprocity Treaty of 1903, which gave Cuban cane sugar preferential treatment in the U.S. market. With prices collapsing, economic consolidation quickly followed. In 1870, British Guiana had 136 sugar estates, with 123 of them having indentured servants. By 1900, the number of plantations had fallen to fifty and would further fall to nineteen by 1950. Ownership of the plantations also changed hands from individual planters to shipping and transport companies. In 1900, the two leading sugar operators—Booker Brothers and John McConnell and Company—combined to form Booker Brothers McConnell and Company Limited, a London-based, limited liability company. Booker Brothers had a virtual monopoly in sugar production, controlling eighteen of the surviving nineteen plantations. Booker Brothers also owned a host of retail, manufacturing, and transport services in British Guiana. In the twentieth century, Guyanese jested that British Guiana should be called “Booker’s Guiana.”

15 The company had the same overwhelming presence in the colony as did United Fruit Company of Boston in Honduras and Guatemala.

Political and economic change came slowly to British Guiana during the first forty years of the twentieth century. Colonial authorities allowed a modicum of political freedom. Workers gained the right to join unions, with sugar workers forming in the Manpower Citizen’s Association in the 1930s. The colony also permitted ethnic organizations, like the League of Coloured Peoples and the British Guiana East Indian Association, to articulate their respective group’s concerns. Property requirements for voting were also slightly relaxed, giving a few thousand colonists the right to vote for advisers to the colonial governor. The Colonial Office in London actually strengthened its hold on the colony, making British Guiana a “crown colony” with a royal governor in 1929, whereas in the nineteenth century, the governor had shared power with the sugar barons. The colony’s economy made minimal progress. The prices for sugar and rice soared during World War I but collapsed during the global depression of the 1930s. Mining for bauxite began in 1914, centering about seventy miles up the Demerara River near Linden. Canadian metals companies began to invest in the colony. The colony’s population grew throughout the period, reaching 375,701 at the end of World War II. Efforts to control malaria had helped reduce mortality rates for rural people. Indians had become the largest group in the colony with 163,343 people. British Guiana’s blacks numbered 143,385.

16By the end of the 1930s, the economic hardships engendered by the global depression had fueled discontent in the British possessions in the Western Hemisphere. Violent strikes and demonstrations erupted in Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad, and British Guiana. Between 1935 and 1938, workers repeatedly protested their life and work in British Guiana’s sugar plantations. The Colonial Office dispatched in 1938 a study team, the Moyne Commission, to investigate and make recommendations. The commission’s report, which was withheld until after World War II, documented the deep poverty in the British West Indies and lack of educational and employment opportunities. It also noted that the populations of the colonies were growing rapidly. British Guiana’s population would grow at the rate of 3.3 percent a year from 1946 to 1960. The Moyne Commission wanted London to expand suffrage, invest in the colonies, and enact far-reaching socioeconomic reforms.

17Change in British Guiana and throughout the British West Indies would ensue less, however, from internal reforms and more from external pressures. British Guiana was one of the most isolated parts of the empire, with Indians being especially cut off. But the aspirations and grievances of the outside world gradually intruded into British Guiana. Literate colonists learned of the promises of national self-determination made in Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points (1918) and the Atlantic Charter (1941). Guyanese also followed the struggles for independence launched by Mahatma Gandhi in India and Kwame Nkrumah in the African Gold Coast (Ghana). Great Britain emerged from World War II badly weakened and in little position to make the financial commitments called for by the Moyne Commission. Furthermore, during the war, the United States developed a significant presence in British possessions in the Western Hemisphere. As part of the “destroyers for bases” deal of 1940, the United States developed military bases throughout the region, including an airfield, Atkinson Field, in British Guiana. The U.S. military assumed the defense of Great Britain’s hemispheric possessions during the war. U.S. advice inevitably followed U.S. military aid. The Franklin D. Roosevelt administration dispatched a team of experts, the Taussig Commission, to study conditions in Jamaica. U.S. diplomats pressed the British to initiate economic reforms and to sponsor economic diversification projects. Domestic civil rights groups, like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), questioned the treatment of blacks in the British possessions.

18 As reflected in the Fourteen Points and the Atlantic Charter, the United States opposed colonialism in principle. President Roosevelt also had a strong aversion to European colonial empires and was determined to use the war as an opportunity to dismantle them. Decolonization would also benefit the postwar U.S. economy, opening British colonial possessions in the Caribbean region to U.S. trade and investment.

Gaining experience in the outside world proved critical to the personal development of British Guiana’s anticolonial leaders, Forbes Burnham and Cheddi Jagan. Both men, who studied abroad, would bring a global outlook to a largely impoverished, unaware population. Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham (1923-85) was born in Kitty, a suburb of Georgetown, into the small black professional class. He was the second of five children. His father served as headmaster of a Methodist primary school. An outstanding student, in 1942 Burnham won the Guiana Scholarship, the colonial government’s yearly award to the top student in British Guiana for study in Great Britain. At the conclusion of the war, Burnham entered the University of London where he earned a law degree in 1947 and subsequent admission to the bar at Gray’s Inn. Burnham won academic awards from the law faculty for his public-speaking abilities. Observers always commented on Burnham’s dignified personal style and remarkable communication skills. A handsome man, the young Burnham dressed neatly in a suit with a bow tie. He conversed in a calm, unhurried, thoughtful manner, befitting a lawyer. V. S. Naipaul, the Nobel laureate in literature, who heard Burnham speak both at Oxford University and in British Guiana, wrote that Burnham was “the finest public speaker I have ever heard.”

19 Burnham also became politically active in student politics, serving as an officer in the West Indies Student Association and as a delegate to the World Youth Festival in Czechoslovakia. Burnham developed relationships with left-wing members of the British Labour Party and with members of the British Communist Party. Burnham usually referred to himself as a socialist. As did other West Indian and African members of the empire who came to Great Britain, Burnham encountered racial discrimination in the mother country. Working with the League of Coloured Peoples, he helped organize demonstrations in London to protest racism. Burnham, who returned to British Guiana in 1949, emerged from his experiences in London with a strong sense of racial pride and an understandable distrust of white people.

20When Burnham returned to British Guiana, he found a colony that had awakened politically. Cheddi Jagan had begun to organize a mass political party. Like Burnham, Jagan achieved much outside of his homeland. Indeed, within a U.S. context, Jagan’s life might have been interpreted within the Horatio Alger “rags to respectability” motif. Cheddi Jagan (1918-97) was born on a sugar plantation, Port Mourant, in the eastern coastal region of Berbice. Jagan’s grandparents arrived from India as indentured servants at the beginning of the twentieth century. His grandparents, reflecting village customs, arranged his parents’ marriage when they were ten years of age. Jagan’s parents worked in the cane fields as small children, with his father eventually achieving the position of gang leader or “driver” on the Port Mourant plantation. Cheddi was the couple’s eldest surviving child in a family that grew to eleven children. His parents were determined that their offspring break out of the intense poverty that had characterized their families’ lives in both India and British Guiana. Jagan’s parents sent him to study at a government secondary school in Georgetown after he received a primary education at a Christian school. In 1936, carrying with him the family’s life savings of $500, Jagan sailed for the United States and Howard University, the famous university established for freedpeople after the Civil War. During the next seven years, Jagan won scholarships at Howard and then transferred to prestigious Northwestern University, where he achieved a degree in dentistry. Jagan supported himself by working at a series of low-wage jobs—patent medicine salesman, pawnbroker, ice cream vendor, elevator operator—in Washington, D.C., New York City, and Chicago.

21Jagan became politically aware during his stay in the United States. In Washington and nearby Virginia, he witnessed the problems Howard University students encountered in the segregated South. He also saw the deep poverty of U.S. blacks when he worked in the neighborhood of Harlem in New York. As an Asian, Jagan was not permitted to work day shifts when he operated elevators in Chicago. These experiences, combined with the collapse of the world order in the late 1930s, led Jagan to enroll in history and political science classes at the YMCA College of Chicago, even as he pursued his dentistry classes. He became impressed with left-wing U.S. scholars, like Charles Beard and Matthew Josephson, and with the Communists, Marx and Lenin. He also admired Roosevelt’s New Deal and became acquainted with the anticolonial ideas of the Indian National Congress. In effect, Jagan engaged in the political ferment that characterized urban life in the United States during the economic depression and the period leading to World War II. Although his political philosophy stemmed from eclectic sources, Cheddi Jagan would later readily accept being called a “Communist.” He once testified: “I am a Communist in accordance with my own views on communism.” Jagan regularly added, however, that he embraced parliamentary democracy and that he equated communism with democratic socialism and the ideals of early Christian communities. Jagan further identified himself as a “Marxist and left-wing Socialist.” Such responses, which often came from Jagan’s lifelong habit of speaking “off the cuff,” regularly baffled both his friends and enemies.

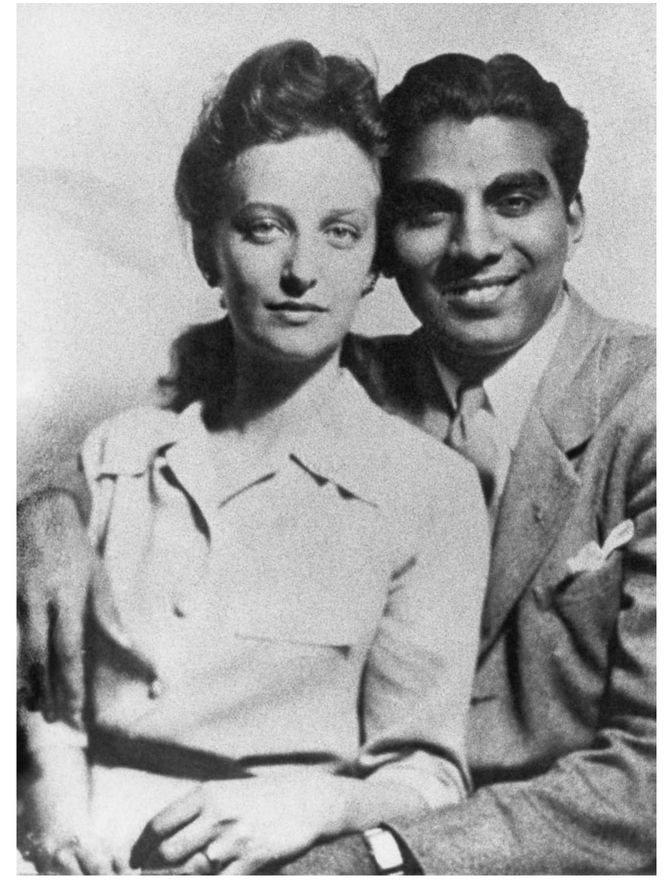

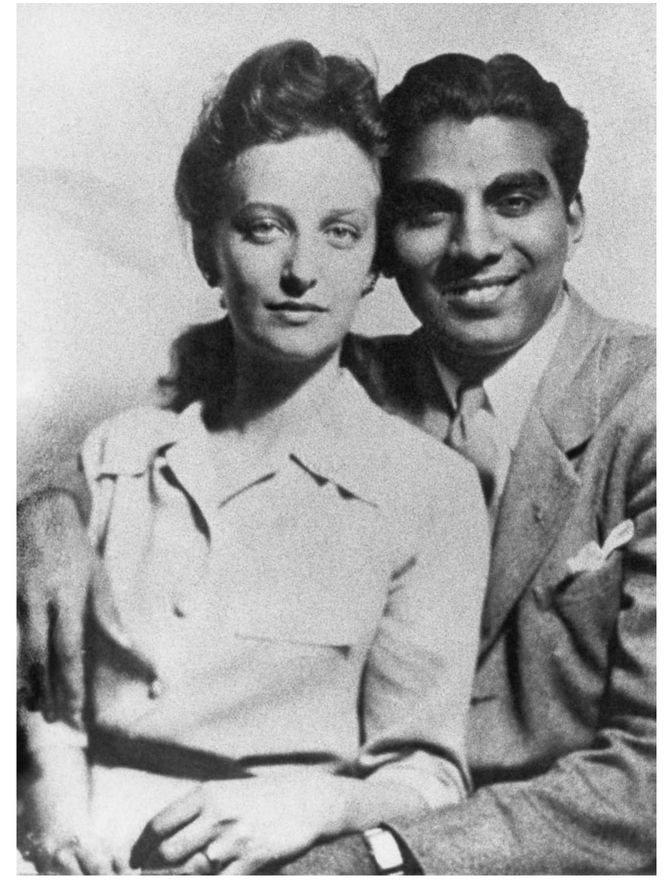

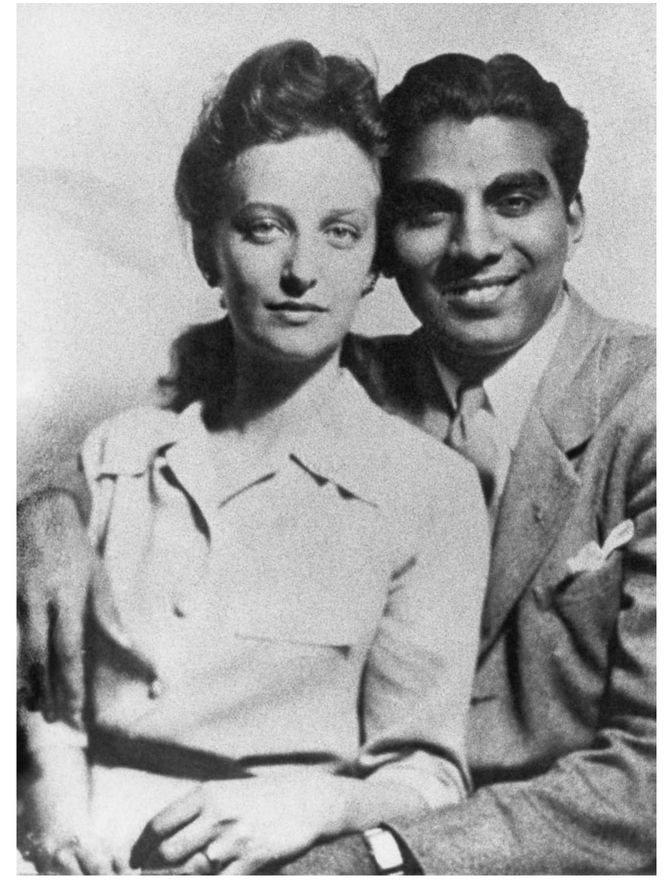

22Jagan’s wife became his political partner. In 1943, Jagan married Janet Rosenberg (b. 1920), who came from a middle-class family and lived in a Jewish neighborhood in the South Side of Chicago. Janet Jagan’s parents were conservative but largely apolitical. The family encountered anti-Semitism, with the father changing his last name to “Roberts” to aid his career as a salesman. Janet Jagan would later claim that her experiences with anti-Semitism fueled her desire to aid the poor and downtrodden. Although she came from a “typical” urban, Jewish family, Janet Rosenberg hardly acted like her female contemporaries of the late 1930s and early 1940s. Independent, self-confident, and perhaps rebellious, she rode horses and became an outstanding competitive swimmer. She frightened her parents, taking flying lessons without their permission. She attended Wayne State University and became involved in left-wing student politics. Labor agitation in the Detroit area and the famous “sit-down” strikes of the 1930s by auto workers had influenced students on the Wayne State campus. Back in Chicago, Janet studied nursing at Cook County Hospital and became a member of the Young Communist League of Chicago. She met Cheddi at political gatherings of international students. Her parents initially opposed the interracial marriage, with her father threatening to shoot Cheddi on sight. They despised his skin-color, religion, nationality, and politics. In fact, Janet’s father, who died in the 1950s, never met Cheddi Jagan. The family predicted that the marriage would not last a year if Cheddi brought his bride to British Guiana. The couple would stay married, however, for over fifty years and have two accomplished children. The Jagans’ wedding photographs depict a gorgeous young couple.

23Cheddi Jagan underwent a personal crisis during World War II. In light of the ensuing U.S. confrontation with Jagan, the crisis is laden with irony. Jagan contemplated living permanently in the United States. He probably also would have served in the U.S. military as an officer and doctor of dentistry. He later admitted that he was philosophically torn between Roosevelt’s internationalism and the studied neutrality of the Indian National Congress. But Jagan was not permitted to take Illinois’s examination to become a licensed dentist, because he was not a citizen. The immigration authorities classified Jagan as an “oriental,” even though he was born in South America. Under prevailing immigration laws, Asians could not readily become citizens. The U.S. Selective Service issued a draft notice in 1943 to the “oriental” Jagan, giving him six months to achieve his dental license. With the only alternative becoming a private in the U.S. military, Jagan returned alone to British Guiana in 1943. Jagan needed time to persuade his family to accept a white, Jewish woman into the family. Janet Jagan dramatically arrived in British Guiana at the end of 1943, landing on the Demerara River on a Pan American seaplane.

24Cheddi and Janet Jagan brought the ideas of the outside world to British Guiana. They joined with Burnham and other Afro-Guyanese, such as trade unionist Ashton Chase who had studied at Ruskin College in England, to transform the colony’s political life. The couple joined a political discussion group that met at the Carnegie Library in Georgetown. In 1946, the Jagans, Chase, and H. J. M. Hubbard, a white Marxist, founded the Political Action Committee, using as a model the Political Affairs Committee of the U.S. union organization, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The founders intended for the new political group, based on the principles of “scientific socialism,” to foster labor and progressive movements in British Guiana. The Political Action Committee quickly attracted Guyanese who called for self-government. In late 1947, Cheddi and Janet Jagan and Hubbard targeted the elections for the colony’s Legislative Council. The Colonial Office had further relaxed the voting requirements, creating an electorate of 60,000. With the help of Sidney King, a black school teacher, Cheddi Jagan appealed to both blacks and Indians and won a seat on the Legislative Council.

25

Cheddi Jagan and Janet Rosenberg Jagan in the United States in 1943. Courtesy of Nadira Jagan-Brancier.

National support for the Political Action Committee broadened in 1948 following a confrontation later celebrated as a momentous event in Guyanese history. Colonial police fired on a crowd of 600 sugar workers protesting changes in work rules on the Enmore Sugar Estate. Five workers died and another fourteen were wounded. Some had been shot in the back. The Jagans led a mass funeral march from the estate to Georgetown. Guyanese would thereafter commemorate the tragedy, making annual pilgrimages to the graves of the “martyrs.” In the aftermath of the Enmore incident, the leaders of the Political Action Committee moved to form a political party. Borrowing ideas from Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party in the United States and Norman Manley’s People’s National Party in Jamaica, they established the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) in 1950. The PPP’s platform called for an independent nation built on socialist principles. The party’s leadership reflected the multiracial nature of colonial society. Blacks and Indians shared the top posts. Janet Jagan edited the party organ,

Thunder. Clinton Wong, a Guyanese of Chinese background, became a vice chairman. The party tapped Forbes Burnham as chairman; after leaving London in 1949, Burnham had stopped in Jamaica to study the organization of the People’s National Party. With Burnham as chairman, the PPP had a prestigious leader with, in Jagan’s words, “an impressive scholastic record.”

26The PPP’s founders undoubtedly hoped that nationalist aspirations, a shared sense of historical injustice, and class consciousness would overwhelm whatever ethnic, racial, and religious tensions existed in the colony’s diverse society. At midcentury, British Guiana had a complex socioeconomic structure that defied facile characterization. Physical, residential, and employment barriers limited communication and interaction among the colony’s now 400,000 people, consisting of Indians, blacks, “mixed” groups, whites, Chinese, and Amerindians. Except for Amerindians, who lived deep in the interior of the country, Guyanese resided in a curious “linear structure,” strung out on a long line along the coast. There was probably less communication between the settlements and distinct cultural groups than there would have been if they had occupied a compact circular or rectangular area. The colonists were mainly rural folk, with about 70 percent living on sugar plantations and nearby villages. Most Indians, who were approaching 50 percent of the population, continued to live a rural life. Georgetown and its surrounding suburbs and New Amsterdam, near the mouth of the Berbice River, constituted British Guiana’s major urban areas. New Amsterdam had just over 10,000 people. Georgetown dominated with about 125,000 people. Like the rest of the country, urban areas were growing because of the colony’s postwar population boom. Blacks, about 40 percent of the colony’s population, mixed groups, whites, and Chinese lived in Georgetown and New Amsterdam.

Employment generally indicated ethnic and racial identity in British Guiana. Sugar production, rice farming, mining, civil service, and education offered work for the colonists. Indians worked as paid laborers on the sugar plantations and owned and farmed the rice-producing lands. Blacks mined the bauxite in regions sixty to seventy miles from the coast near the towns of Mackenzie and Kwakwani, respectively along the Demerara and Berbice Rivers. Blacks and mixed groups dominated the civil service and educational sectors. Most police officers, for example, were Afro-Guyanese. Guyanese of Chinese and Portuguese descent were prominent in the urban merchant trade. Except for Indian rice farmers, few Guyanese owned anything of consequence in the colony. Booker Brothers controlled the sugar plantations, and Canadian and U.S. aluminum companies owned the bauxite industry.

Guyanese were not as separated, however, as raw residential and employment statistics might suggest. Blacks also worked on the sugar plantations and enjoyed a peaceful coexistence with Indians in rural villages. Indians constituted about 20 percent of urban residents. Upwardly mobile Indians, who had learned English and had some education and money, had begun to try to enter the civil service and merchant trade. Although British Guiana’s distinct communities assuredly did not always interact on a daily basis, they nonetheless drew similar conclusions about colonial life. Indians on sugar plantations and blacks in mining camps resented meager wages, endemic poverty, colonial rule, and foreign control of the economy. They pointed to the colony’s persistently high unemployment and underemployment rates. Young men and women found it especially hard to find work in Georgetown. Guyanese were not divided along class lines, because most engaged in the daily struggle to survive. Indians and blacks favored nationalist politicians who promised independence and thoroughgoing, even radical, economic change. At midcentury, Guyanese believed they had compelling reasons to reject imperialism and to disdain the international capitalist system.

27Some scholars, dubbed “cultural pluralists,” have suggested that British Guiana’s politicians could never have constructed a cohesive nation out of this diverse immigrant society. Primarily employing anthropological perspectives, the cultural pluralists argue that under British colonialism blacks and Indians “lived side by side without much mingling.” The two groups developed “very different systems of compulsory or basic institutions.” Nationalism could be a disruptive force, when disparate groups are forced to work together. The “forces of nationalism” would expose cultural differences and “pose a threat to cultural autonomy.”

28 Contemporary observers could have found evidence to support such abstract theories. Afro-Guyanese intellectuals posited that blacks had suffered more under slavery than had Indians under indentured servitude and thereby merited special considerations in the postcolonial era. Moreover, because Afro-Guyanese controlled the lower-level civil service positions in the colony, they naturally assumed they would control real political power when independence came. They also worried about the demographic shifts in the colony, for Indians had a higher birth rate than blacks did. On the other hand, Indian thinkers focused on the horrors of indentured servitude and objected to colonial discrimination. Indians deeply resented the Christian control of schools and the lack of educational opportunity, particularly since illiterates were not permitted to vote. Indians were also uneasy about blacks dominating the police force. Indians further favored government spending that would bring electricity, potable water, and indoor plumbing to rural areas. The urban blacks of Georgetown objected that spending on rural development meant less money for industrial projects and jobs for blacks. Economic development issues seemingly involved matters of race, ethnicity, and religion.

29Other scholars have rejected the racial pessimism of the cultural pluralists. Raymond T. Smith, who wrote one of the first historical studies of British Guiana, noted that “the really interesting thing about British Guiana is not the extent of ethnic differences but the degree to which a common culture already exists.” Smith, who conducted research in the colony in the 1950s, pointed to the triumph of the English language, the common experience of plantation labor, and the agreement among blacks and Indians to end the traditional prerogatives of whites. Both groups were now divorced from their ancestors’ homelands and were committed to creating a distinctly Guyanese identity. Indians took pride in both India’s and Ghana’s independence. Both communities also shared a common passion for the sport of cricket. Smith conceded that Indians rejected denominational schools but also noted that they still admired the English educational system. The historian predicted that economic development and independence would resolve lingering racial tensions. A team of economists seconded Smith’s prediction. In 1952, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development sent a mission to British Guiana to survey the colony’s economic needs. The mission commented on the colony’s lack of rigid social and economic barriers and hoped that the onset of political activity would not impair the “present racial harmony.” The mission conceded that British Guiana had obvious economic challenges, with its “rapidly increasing population confined to a narrow ribbon of the coast, preserved from the encroachments of the sea with great difficulty.” Nonetheless, the mission believed “the problems of the colony can be resolved and its continued progress assured.”

30Whether Guyanese could have built an efficient, harmonious, multiracial community remains a moot issue. As indicated by the formation of the PPP, the colony’s young political leaders envisioned such a country. Such an undertaking would have required great wisdom, forbearance, and love. The European colonial powers had bequeathed a difficult legacy to the Guyanese. Nonetheless, as late as 1962, a multiracial, multiethnic investigative commission dispatched to British Guiana by the Colonial Office reported “little evidence of any racial segregation in the social life of the country and in Georgetown.” The commission added that “East Indians and Africans seemed to mix and associate with one another on terms of the greatest cordiality.” The commission noted, however, that “unprincipled and self-seeking” politicians had already appealed to racial passions and that “there is, of course, always present the danger that hostile and anti-racial sentiments may be aroused by a clash of the hopes and ambitions of rival politicians.”

31 The commission’s forecast of potential danger became a reality. Unscrupulous domestic politicians and a meddling foreign power incited Guyanese to hate one another.

AS GUYANESE ORGANIZED FOR INDEPENDENCE, imperial Great Britain was reassessing its role in British Guiana, and the United States was contemplating its future relations with the colony. Shortly after the defeat of Nazi Germany, the Labour Party led by Clement Attlee defeated Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s Conservatives and retained power until late 1951. Prime Minister Attlee’s government believed that the United Kingdom’s strategic and economic interests would be enhanced by supporting the United States internationally, improving the United Kingdom’s war-ravaged economy, and cutting costs. It judged that initiating the process of decolonization would facilitate reaching those goals. In any case, after two bloody global conflicts and the economic depression of the 1930s, the British had neither the power nor money to hold on to the far-flung and increasingly restive empire. The Attlee government managed to transfer power to India, Pakistan, Ceylon, and Burma. It also transferred its League of Nations mandate over Palestine to the new United Nations. But it did not fix a timetable for independence for its other forty possessions and 70 million colonial subjects, most of whom lived in Africa. It held that economic development must precede independence. In the words of George Hall, the Colonial Office secretary, the mother country would help develop the colonies “so as to enable their peoples speedily and substantially to improve their economic and social conditions, and, as soon as practicable, to attain responsible self-government.” This limited pledge disappointed many colonists.

32The Attlee government’s policy of guided decolonization was readily apparent in British Guiana. In 1950, the government dispatched a study team to British Guiana headed by Dr. E. J. Waddington, a veteran colonial officer who had served in the colony, and Dr. Rita Hinden, a South African economist. The decision to send the Waddington Commission reflected not only the new imperial policy but also London’s concerns about the violence of 1948 and the unresolved socioeconomic problems highlighted by the Moyne Commission of 1938. The Commission recommended a new constitution for the colony. All adults over twenty-one who spoke English would have the right to vote. Property and income tests for voting would be abolished. A bicameral legislature would be established with Guyanese having the right to elect members of the lower House of Assembly. An Executive Council, presided over by the royal governor, would govern the country but the majority of its members would come from the House of Assembly. The governor retained, however, absolute veto powers and the right to certify elections. In presenting the constitution, which the Colonial Office accepted on 6 October 1951, the Waddington Commission noted racial separation existed in British Guiana but predicted integration when Indians became involved in self-government.

33 PPP leaders objected that the Waddington Constitution did not grant independence but conceded that it was “one of the most advanced colonial constitutions for that period.”

34 The vast majority of Guyanese would have their first opportunity to vote in April 1953.

Until April 1953, imperial officials gave scant attention to British Guiana. Although its population had grown to 450,000 in 1953, Guyanese constituted less than 1 percent of colonial subjects. The colony was poor, and London did not consider British Guiana’s sugar, rice, and bauxite to be vital to the health and security of the United Kingdom. In early 1953, the Colonial Office transferred Sir Alfred Savage, who had been the royal governor in Barbados for four years, to British Guiana. In the Colonial Office, midlevel officers supervised the colony. They estimated that the PPP’s political strength was growing and that it might emerge as the strongest party in the 1953 elections. Officials worried about the Jagans’ contacts with international Communists. Cheddi Jagan had attended a world youth festival in Berlin and had come back impressed with East Germany. Janet Jagan had traveled to Copenhagen to attend a conference of the Women’s International Democratic Federation. While touring British Guiana in 1952, N. L. Mayle of the Colonial Office told Cheddi Jagan “that he acted very much like a Communist.” On the other hand, Mayle had previously reported to his superiors that “the Jagans were checked with Security recently and reported not to be Communist.” They allegedly had, however, received Communist Party literature through the mail.

35As British Guiana prepared for its first national election, the colony’s future was again altered by elections in Great Britain. The Conservatives, led again by Winston Churchill, regained power in October 1951. Churchill and his colonial secretary, Oliver Lyttleton, took pride in the British Empire. Colonialism to Churchill meant “bringing forward backward races and opening up the jungles.” Decolonization, if it came, needed to be measured, and change had to be kept within bounds.

36 As Lyttleton wrote, “the dominant theme of colonial policy had to be the careful and if possible gradual and orderly progress of the colonies towards self-government within the Commonwealth.” His words reflected a marked shift of emphasis on the speed and possibilities of decolonization from even the limited pledges offered by Labour. In his memoirs, Lyttleton suggested that the pace of progress depended on how many whites resided in a particular colony. He complained that he could find few wise leaders in Africa. Lyttleton and Churchill forcibly suppressed rebellions in Malaya and Kenya.

37 As for British Guiana, Churchill lamented, as the colonial subjects voted in 1953, that his government was “committed to this new Constitution by our predecessors.”

38The elections of 1953 and the political leanings of Guyanese politicians also began to spark some concern in the United States about British Guiana. Prior to 1953, the United States had virtually no interest in the British possession. U.S. officials had taken notice of the colony at the end of the nineteenth century, when the Grover Cleveland administration, led by Secretary of State Richard Olney, confronted Great Britain over the issue of the proper boundary between British Guiana and Venezuela. But the Venezuelan Boundary Crisis of 1895 had little to do with the British possession. It was about the United States establishing its dominance in the Western Hemisphere, forcing the British to concede, in Olney’s colorful language, that the United States was “practically sovereign” in the region and that “its infinite resources combined with its isolated position” rendered it “master of the situation.” After World War II, the U.S. deactivated the military base Atkinson airfield. U.S. trade with the colony was minuscule and, as late as 1960, U.S. investments in British Guiana amounted to only $30 million. U.S. strategic planners considered bauxite a critical wartime natural resource, and British Guiana produced about 25 percent of the world’s output. Planners concluded, however, that U.S. and Canadian aluminum companies had several sources of supply, including Jamaica and Surinam.

39The U.S. Department of State oversaw reporting on British Guiana but, reflecting U.S. neglect of the colony, actually closed the U.S. consulate in Georgetown in early 1953 in order to save money. Between 1953 and 1957, consular officers reported on British Guiana from the vantage point of Trinidad and Tobago, several hundred miles from Georgetown. Prior to 1953, consular reporting mirrored Colonial Office analyses. Consular officers noted the growing strength of the PPP and reported on the travels of the Jagans. They also forwarded to Washington, without comment, documents like the Waddington Commission’s report and the political platform of the PPP. American Cyanamid’s decision in 1952 to close its operation in British Guiana and release its 500 employees sharply reduced the U.S. presence in British Guiana. The company determined that Jamaica produced a higher quality of bauxite than the metal mined in British Guiana.

40The new U.S. president, Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953-61), initiated a colloquy with Winston Churchill that indirectly touched on British Guiana. Eisenhower found fault with the prime minister’s decision to slow the decolonization process. In a private letter, the president urged his wartime comrade to give a speech on the right of self-government. The Western nations needed to embrace the spirit of nationalism in the world. Eisenhower noted that he longed “to find a theme which is dynamic and gripping and which our two countries can espouse together.” Churchill should tell the world that within a space of twenty-five years every one of the British possessions will have been “

offered a right to self government and determination.” Eisenhower predicted that Churchill would “electrify the world” with his speech. Prime Minister Churchill declined Eisenhower’s challenge. Colonialism was a positive good, rescuing India from its “ancient forms of despotic rule.” Reflecting the racism that underlay the imperial mind, Churchill further noted, “I am a bit skeptical about universal suffrage for the Hottentots even if refined by proportional representation.” Great Britain would maintain its graduated policy of decolonization even though Churchill despised the dismantling of the empire. Instead of an electrifying speech on self-government, the aging Englishman wanted his “swan song” to be about “the unity of the English-speaking peoples” and their special ability to resolve the world’s problems.

41President Eisenhower reminded Churchill that nationalism could be channeled against the power of the Soviet Union. U.S. and United Kingdom support for the principle of national self-determination could be contrasted favorably with the Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. Eisenhower admitted, however, that Communists could take advantage of areas not ready for self-rule. Churchill confidently told aides that the president’s anticommunism would triumph over his anticolonialism. Eisenhower accepted the fundamental finding of National Security Council Memorandum No. 68 (NSC 68), which the Harry S. Truman administration secretly adopted in 1950: the Soviet Union directed the international Communist movement and was bent on world domination. Indeed, according to NSC 68, an apocalyptic struggle loomed, with the Soviet Union intending to subvert or destroy the “integrity and vitality” of the United States.

42 Eisenhower worried, however, that NSC 68, which called on the United States to confront the Soviet Union globally with massive military power, might bankrupt the U.S. economy. President Eisenhower replaced NSC 68 in 1953 with his own national security paper, NSC 162/2, which summoned the United States to strengthen its nuclear forces. Eisenhower further proved ready to authorize the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to carry out covert interventions. He ordered the CIA to attack nationalist leaders in Iran in 1953 and Guatemala in 1954. Eisenhower and his advisers feared that Iranian and Guatemalan nationalists were either Communists, friendly to Communists, or blind to the international Communist conspiracy.

43 Such thinking repeatedly characterized U.S. analyses of British Guiana after 1953.

Although neither the United Kingdom nor the United States would think hard about British Guiana until after April 1953, one nongovernmental organization, the U.S. trade union movement, had already begun to make up its mind about the Jagans and the PPP. By the end of the 1940s, both major labor organizations in the United States, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), had enlisted in the Cold War. Since the late nineteenth century, the AFL had favored “business unionism,” meaning AFL unions would negotiate higher wages and better work conditions for its members but would not challenge the basic capitalist system. The AFL rejected political radicalism at home and always displayed implacable hostility toward the Soviet Union. In 1944, for example, George Meany, the secretary-treasurer of the AFL, voted for Republican Thomas Dewey over Franklin Roosevelt, because he judged Dewey more capable of handling the Soviet Union in the postwar world. This was a remarkable vote, because union leaders heartily approved of Roosevelt’s New Deal domestic programs. In 1944, Meany, along with veteran unionists like David Dubinsky and Matthew Woll, established the Free Trade Union Committee to promote the AFL’s ideas abroad. Meany named Jay Lovestone the secretary-treasurer of the new organization. Lovestone had been a prominent member of the American Communist Party in the 1920s and 1930s, but he soured on the Soviet Union and its leader, Joseph Stalin, and broke with the party in the late 1930s. Lovestone, who controlled the union’s international activities from 1944 to 1974, became a ferocious anticommunist and inveterate cold warrior. Although largely unknown to the public, Lovestone played a critical role in the making of U.S. foreign policy. Lovestone acted with the full knowledge and support of Meany, who served as president of the AFL from 1952 to 1979. Both men had direct access to presidents, secretaries of state, and CIA directors, especially when Democrats controlled the White House.

44The CIO eventually followed the lead of the AFL in international affairs. Famous for their “sit-down” strikes in automobile plants in the 1930s, the CIO initially accepted Communists in its movement. By the end of the 1940s, the CIO had purged Communists from its ranks. CIO leaders, led by Walter Reuther, concluded that American Communists were more loyal to the Soviet Union than the United States and that Communist ideology and practices were incompatible with independent trade unionism and a progressive, free society. Many unionists were also members of the traditionally anticommunist Roman Catholic Church and were of Eastern European heritage and naturally resented the Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. Internationally, the CIO at first worked with Communist unions. In 1945, the CIO, along with its British counterpart the Trade Unions Council (TUC), established the World Federation of Trade Unions. The AFL denounced the new organization because it included unions from the Soviet Union. Both the CIO and TUC left the World Federation of Trade Unions when the organization, under Soviet pressure, refused to support the Marshall Plan. For the TUC, the Marshall Plan meant rebuilding the battered economy of the United Kingdom and seeing British unionists back on the job. The CIO, which closely identified with the Democratic Party, felt obligated to support President Truman’s Cold War policies. By 1950, the CIO had adopted the same Cold War positions as the AFL. The two unions merged in 1955, with George Meany serving as president.

45The AFL-CIO went from supporting U.S. foreign policy to implementing it. Lovestone organized the union’s International Affairs Department to mirror the bureaucratic structure of the State Department. Lovestone dispatched agents around the world and advised the State Department on who should be assigned the position of labor attaché in U.S. embassies. Unknown to rank and file members or U.S. taxpayers, Lovestone’s operation was principally funded by public money. Beginning in 1948, both the AFL and CIO accepted CIA funds and joined the fight against Communist unions in France and Italy. CIA agents worked undercover as union organizers. The AFL-CIO also served as conduit for the dispersal of CIA funds abroad. The CIA, which paid Lovestone’s salary, gave him direct access to the legendary spy, James Jesus Angleton. There is no reliable accounting of how much CIA money the unions handled from 1948 to 1967, when the connection was first publicly exposed. In British Guiana alone, the AFL-CIO probably spent millions of CIA dollars. Labor historians who have studied the issue believe that Meany, Lovestone, and others cooperated with the CIA because historical evidence proved to them that workers always lost their basic political rights under communism, whether in the Soviet Union or in Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe. U.S. labor leaders also probably enjoyed being near the seat of power and having presidents, generals, and foreign leaders asking for their covert assistance.

46U.S. unions first began denouncing Cheddi and Janet Jagan and the PPP in January 1951, calling the PPP “the Communist party of the colony.” Serafino Romualdi, a protégé of Lovestone and president of Inter-American Regional Organization (ORIT) headquartered in Mexico City, made the first allegation against the PPP. Both the AFL and the CIA backed ORIT. British Guiana came to Romualdi’s attention because the Jagans had challenged the Manpower Citizen’s Association’s representation of the sugar workers. In fact, many Guyanese had concluded that the sugar workers union was little more than a “company union,” unwilling to bargain hard with the sugar producers led by Booker. The leaders of the sugar workers union, such as Lionel Luckhoo, had ties to U.S. and British union officials and warned them that the Manpower Citizen’s Association was being threatened by Communists. They further averred that Cheddi Jagan associated with the now Communist-dominated World Federation of Trade Unions. Romualdi accepted their arguments and became a dedicated foe of the Jagans.

47After receiving alarming reports from Romualdi, Lovestone launched his own investigation in 1953, dispatching Dr. Robert J. Alexander of Rutgers University to investigate British Guiana. Alexander was a prominent political scientist and student of Latin American politics who frequently conducted fact-finding missions in Latin America for Lovestone. Alexander, a prolific scholar, published a study on communism in Latin America. Alexander became a good friend of the Venezuelan democratic, anticommunist leader, Rómulo Betancourt, and he helped design President Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress economic development program for Latin America. In a six-page, single-spaced typewritten report to Lovestone, Alexander repeated Romauldi’s assertion that the Jagans were Communists, although he conceded that the PPP was “not a disciplined Stalinist party.” He pointed out that Janet Jagan had been a member of the Young Communist League, and he guessed that she was the “brains behind the organization.” Alexander thought Forbes Burnham not to be a Communist. The political scientist offered no hard evidence to substantiate his opinions. His method of inquiry was to talk to Guyanese. Alexander referred to the Manpower Citizen’s Association as “our people” and wrote that the organization had helped the workers. He conceded, however, that the sugar workers still lived in huts used by black slaves in the nineteenth century. He further noted that the sugar union opposed Cheddi Jagan’s proposed legislation modeled on the Wagner Act of the United States. The Wagner Act of 1935, which established the National Labor Relations Board, empowered workers to choose their own bargaining representatives. The legislation had, for example, given a great boost to the CIO. Nonetheless, Alexander advised Lovestone to contact the State Department about the Jagans, which Lovestone apparently did.

48 Probably unbeknownst to the Jagans, Romualdi and Lovestone had decided by 1953 to become their lifelong enemies.

ALTHOUGH THE COLONIAL OFFICE and the State Department had misgivings about the PPP, and U.S union officials had grave fears about the party and the Jagans, the voters of British Guiana showed no anxieties about handing power to the multiracial party led by Cheddi Jagan. On 27 April 1953, the PPP astonished even itself by winning eighteen of the twenty-four seats in the House of Assembly. The party also celebrated the multiracial nature of its triumph. One of its Afro-Guyanese candidates won the seat in a majority Indian district. Janet Jagan also won a seat. The party badly defeated the National Democratic Party, a multiracial party composed of British Guiana’s small, conservative middle class. The National Democrats won only two seats. The victorious party chose its six members—three blacks and three Indians—for Governor Savage’s Executive Council. Both Cheddi Jagan and Forbes Burnham were among the six who joined the Executive Council. In April 1953, the PPP established a precedent that has held throughout the colony and nation’s political history: whenever a free and fair election has been held, the PPP has garnered the most votes.

The PPP shocked the colonial establishment with the speed and manner in which it moved to enact its electoral promises. PPP representatives were young, brash, and perhaps impolitic. They violated British protocol, not bowing at the proper times during legislative functions. They further offended colonial sensibilities by declining to spend money to send representatives to Jamaica to greet the new queen, Elizabeth II. The party organ,

Thunder, engaged in political hyperbole. The PPP also took on the world, passing a resolution urging President Eisenhower to grant clemency to Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, the convicted atomic spies. As Cheddi Jagan wryly noted afterwards, Pope Pius XII made a similar plea to Eisenhower.

49 Although PPP representatives may have behaved immaturely, what they proposed in 1953 for British Guiana easily fit within the traditions of the Democratic Party of the United States, the Labour Party of Great Britain, and the Indian National Congress. The PPP’s platform had promised measures to improve the working and living conditions of the colony’s downtrodden majority. The proposals included support for low-cost housing, workmen’s compensation, schemes to increase land ownership, new taxes on the wealthy, and public education. Such measures implied the transfer of some power to the poor and predictably evoked, as it had against Roosevelt’s New Deal, cries of “communism.” Outrage among the political opposition mounted when the PPP voted to repeal the Undesirable Publications Act, a ban on “subversive” literature. With sugar workers on strike, political warfare broke out in September 1953 over British Guiana’s version of the Wagner Act, which would give workers the right to choose their bargaining agent. The PPP actually modified the bill, requiring a 65 percent vote of workers, instead of 51 percent, if workers wanted to decertify an existing union, like the Manpower Citizen’s Association.

50British imperial authorities in London assumed that the PPP would carry out a Communist revolution in British Guiana. Like most Guyanese, the Colonial Office predicted that the 1953 election would reveal a divided electorate. Prime Minister Churchill was shocked to hear of the PPP’s victory and on 5 May 1953 asked Colonial Secretary Oliver Lyttleton whether he had to accept the result. Churchill added that “we ought surely to get American support in doing all we can to break the Communist teeth in British Guiana.” Churchill also joked that “perhaps they could even send Senator [Joseph] McCarthy down there,” referring to the reckless anticommunist extremist from Wisconsin. Lyttleton responded that Governor Savage was unworried, because the PPP’s platform was moderate or, as the Colonial Secretary put it, “no more extreme than that of the Opposition here.” The major concern was that some PPP leaders had visited Communist countries. Lyttleton reminded Churchill, however, that the governor retained extensive veto powers. Lyttleton added that the Colonial Office adamantly rejected the suggestion of seeking U.S. assistance on British Guiana. The colonial secretary assured the prime minister that he would monitor the colony’s politics.

51Despite Governor Savage’s optimism, anti-PPP diatribes quickly arrived at the Colonial Office. J. M. “Jock” Campbell, the director of Booker Brothers, called on the Colonial Office in June 1953 and pointedly asked if the government would act if his sugar business was disrupted by the PPP. Campbell implied that Governor Savage was not tough enough with the PPP. The Demerara Company of Liverpool passed on a report that alleged that “communism is openly on the rampage” and that British Guiana was run by a “body of unscrupulous Communist gangsters.”

52 Less colorful but no less dangerous to the PPP were the analyses prepared by officers within the Colonial Office. By mid-July 1953, less than three months after the election, officers were speaking of banning the PPP. As James N. Vernon of the Colonial Office saw it, “Communism is an international faith and with Communists or near-Communists in the Government the international repercussions of their actions cannot be ignored.” British Guiana could become a “center” of the Communist organization. The Colonial Office objected to PPP’s civil liberties campaign. The PPP had overturned the subversive literature ban and then lifted the ban on suspect West Indian leaders visiting British Guiana. “Secret sources” informed the Colonial Office that Janet Jagan had once met Harry Pollitt, the leader of the British Communist Party, and that Cheddi Jagan had asked for literature from the World Federation of Trade Unions. In a radio interview, Jagan had also said he admired the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. The Colonial Office especially worried about Janet Jagan, for she was “an exceptionally able, ruthless, and energetic woman” who was “the dominating influence in the party.” As for Forbes Burnham, the Colonial Office considered him “violently anti-British, anti-white, and lacking in balance and judgment.” For good measure, officers added that Burnham was “lazy, flippant, and sarcastic.” By August 1953, the Colonial Office had concluded that the government needed to revoke British Guiana’s constitution and remove the PPP from power.

53Governor Savage did not encourage such extreme measures. In his reporting to London, the governor set another pattern in the saga of British Guiana that would persist through the 1950s and 1960s. Diplomats who actually served in the colony argued that political life in British Guiana was complex and did not easily fit into the structures of the Cold War. British Guiana had its own troubled history separate and apart from the East-West confrontation. Savage pointed to the PPP’s surprising ability to maintain a biracial coalition, although he acknowledged that racial tension persisted in the colony. PPP leaders were inexperienced and also bitter about the colony’s treatment by past governments and big business. Savage thought that moderates and constitutional processes could ultimately triumph. He did not accuse anyone of being a Communist. He dubbed Janet Jagan and Sidney King, a member of the Executive Council, as “acknowledged Communists,” meaning “generally acknowledged to be Communists by others.” Governor Savage never recommended military intervention in British Guiana, and it “came as a great shock to us” when it happened.

54 The Colonial Office would later criticize Savage for not being forceful enough and for being dedicated to the common man. Savage confessed to having “sympathy for coloured people.”

55Governor Savage received backing in his analysis of the PPP from another British official stationed in British Guiana, D. J. G. Rose, chief of the colonial intelligence services known as the “Special Branch.” Rose flatly discounted any plot or conspiracy in British Guiana, noting that Cheddi Jagan had shown no sign of subordinating his ambition to be a successful leader of the colony to any “International design by International communism for creating chaos.” Jagan’s only experience with communism came when he visited East Germany. Rose opined that Jagan was a hero to Indians, because they were intensely anticolonial based on their dire poverty and history of suffering in the sugarcane fields. The black urban laborers held Burnham in similar esteem. Like Savage, Rose noted that the biracial leadership of the PPP had helped relax racial tensions. Rose principally worried about Janet Jagan, an “orthodox Communist.” Her husband was “a misguided colonial intellectual” who leaned on her during times of stress. Rose alleged that Cheddi Jagan had learned about communism from his wife and wondered whether Janet Jagan could “dominate her husband’s plans.” Rose vowed to be watchful to insure that Janet Jagan did not “dominate her husband.”

56Savage and Rose’s reports made no impression on the Churchill government. By late September, the prime minister, after checking with his cabinet, ordered Lyttleton to stop what the Colonial Office called a brewing “Communist conspiracy.”

57 On 9 October 1953, upon instruction from London, Governor Savage suspended the constitution and took full control of the colony. British troops, who were stationed on warships, had already landed in British Guiana. The PPP had held power for a mere 133 days. Colonial Secretary Lyttleton explained that he acted because he had received reports from intelligence services of plots to burn down Georgetown, which consisted largely of wooden buildings. Guyanese who did not own automobiles were purportedly obtaining petrol and kerosene. Lyttleton’s allegations would have had no standing in a British court of law. As Governor Savage later explained, the information that colonial police obtained on arson and sabotage plots came from paid informers who had second- and third-hand sources.

58 Churchill’s government had reoccupied British Guiana because it wanted to demonstrate to nationalist movements throughout the empire that it would control the pace and direction of decolonization.

59The Labour opposition initially issued a sharp public challenge to the intervention, prompting the government to issue a “White Paper.” British officials privately conceded that it would be “convenient” to say that the intervention forestalled a Communist plot. Because such an allegation was not “tenable,” the White Paper emphasized maladministration, disorder, and the potential for violence and bloodshed. It further pointed to the Communist associations of PPP leaders and suggested that their legislative initiatives represented a blueprint for Communist domination. Party officials were “zealots in the cause of communism.”

60 The Colonial Office provided, however, no evidence proving that PPP leaders worked with or accepted support from international Communists based in the Soviet bloc. It also did not prosecute PPP leaders, although Lyttleton reportedly personally threatened Jagan and Burnham with imprisonment.

61 Labour Party spokesmen had observed that if the government knew that Jagan, Burnham, and others were potential arsonists then they should present that evidence in a legal setting. Cheddi and Janet Jagan each served five hard months in prison in 1954 but that was for engaging in proscribed political activity and travel after the suspension of the constitution.

Although Labour members pointed to inconsistencies in the government’s arguments, the Labour Party proved a disappointment to the PPP. After the military occupation, Jagan and Burnham journeyed to London and met with Clement Attlee. The interview went badly with Attlee objecting to both past associations of PPP leaders and their inflammatory rhetoric. Labour felt more comfortable with Caribbean leaders, such as Grantley Adams of Barbados and Norman Manley of Jamaica, who were nationalists and vocal anticommunists. Rita Hinden, who had served on the Waddington Commission, further hurt the PPP cause when she accused the PPP leadership of not accepting democratic values and of attempting to create a one-party state in British Guiana. Hinden had helped establish the Fabian Colonial Society, an association which lobbied for colonial self-rule and the orderly move toward independence.

62 In fact, the PPP had not bothered to consult with its small, scattered opposition. Jagan would later acknowledge that “we allowed our zeal to run away with us, we became swollen-headed, pompous, bombastic.”

63 In the House of Commons, Labour tried to have it both ways, “condemning methods toward the establishment of a totalitarian regime” but noting that it was “not satisfied that the situation in British Guiana was of such a character as to justify the extreme step of suspending the constitution.” The Conservatives handily defeated the resolution. Oliver Lyttleton laughed at Labour’s meek and mealy effort. He taunted that “the amendment was nearly all soda water; only a drop of whiskey could be risked.”

64In parliamentary debates, Lyttleton denied Labour suggestions that the United States had pressured the government to send troops to British Guiana. On that issue, Lyttleton spoke truthfully. Contemporary observers and foreign nations assumed that the United States urged the British to remove Jagan. Indeed, when a U.S. diplomat called in Georgetown after the suspension of the constitution, wealthy Guyanese thanked the diplomat, persistently asserting “that the United States deserved all the credit.”

65 Scholars have also implied that the United States played some role.

66 Although Churchill and the Colonial Office perceived a U.S. interest in British Guiana, they did not receive meaningful advice or guidance from the Eisenhower administration. Colonial officers frequently expressed the view that “in the case of British Guiana there were external considerations such as our position in the Caribbean and our relations with South America and the United States which must inevitably be taken into account in determining our policy.” Such external considerations mattered less, however, to the Colonial Office than their conviction that the PPP was misruling a British colony. At a meeting of Churchill’s cabinet on 2 October 1953, cabinet members agreed that the United States should be informed of the invasion plan only twelve hours before it went into effect.

67 Prime Minister Churchill was always keen, of course, on preserving imperial prerogatives.

Without a diplomatic presence in British Guiana, the United States could not readily shape events in the colony. Consul Thomas P. Maddox reported on British Guiana from Port of Spain, Trinidad. Maddox read Guyanese newspapers, most of which were violently anti-PPP, and interviewed those who had been in British Guiana. The other source of hearsay information for the State Department was its embassy in London. One officer, Second Secretary Margaret Joy Tibbetts, read British newspapers and conversed with officers in the Colonial Office. In mid-1953, the State Department received a firsthand account of the colony’s politics when it ordered Consul Maddox to visit British Guiana. In part, department officials were reacting to an article in the conservative news magazine,

Time, that declared that the election of 1953 “returned the first group of Communist leaders ever to rule in the British Empire.”