CHAPTER THREE

COVERT INTERVENTION, 1961-1962

Iain N. MacLeod, who served as secretary of state for colonies in Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s cabinet, recounted an exchange that he had with President John F. Kennedy in the White House. “Mr. President,” Macleod queried, “do I understand that you want us to go as quickly as possible toward independence everywhere else all over the world but not on your doorstep in British Guiana?” According to Macleod, Kennedy laughed and then responded, “Well, that’s probably just about it.”1 The ironic banter between the two officials masked the grave consequences that portended for the small British colony in South America. In the name of anticommunism, the Kennedy administration took extraordinary measures to deny the people of British Guiana to right to national self-determination. U.S officials and private citizens incited murder, arson, bombings, and fear and loathing in British Guiana. Indeed, the covert U.S. intervention ignited racial warfare between blacks and Indians. By the end of 1962, the United States had forced the United Kingdom to accede to U.S. demands to find a way to deny power to Cheddi Jagan and the People’s Progressive Party.

THE YEAR 1961 WOULD BE the last tranquil year that Guyanese would enjoy for more than three decades. The year would be characterized by peace, relative prosperity, free elections, and hope that British Guiana would soon win its independence. U.S. consular officials in Georgetown characterized 1961 as the “most prosperous year in British Guiana’s history.” Export sales of sugar and rice grew by 20 percent during the year. The colony opened its first manganese mine. Per capita income grew to $384. British Guiana remained poor, but its level of economic activity was substantially higher than many of its small Caribbean and Central American neighbors, whose per capita incomes were well below $200. Trade accounted for more than half of economic activity, with British Guiana remaining firmly tied to the West. The colony sold approximately 75 percent of its agricultural products and minerals to the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States and purchased more than two-thirds of its imports from the same three countries. British Guiana also sold substantial quantities of its surplus rice to Cuba for cash, accounting for about 6 percent of its exports. Canadians in minerals and the British in sugar remained the key private investors in the colony. British Guiana’s long-term prospects still depended on attracting outside capital, because the country had to spend extraordinary amounts of money on public works, keeping the coastal plain dry. The population, now about 600,000, continued to grow, especially in the countryside, as rural Indians reaped the benefits of successful campaigns to eradicate malaria. The antimalarial campaign involved the extensive spraying of the pesticide DDT.

2Cheddi Jagan interpreted the colony’s economic growth as the “crowning achievement” of his rule since 1957. He was everywhere, seeking business and asking for help. At the end of 1960, Jagan was back in Washington looking for loans. The United States continued to review loan applications, maintaining only the small technical assistance program of $300,000 to $500,000 a year. The Colonial Office would not permit Jagan to accept the $5 million loan offer from Fidel Castro’s Cuba, although it approved of the rice sales. In mid-1961, Jagan was back in Caracas trying to strike a rice deal. Jagan also contacted East Germany about rice milling equipment. East Germany had earlier offered scholarships for four students to study in Leipzig. The Colonial Office thought that Guyanese students would find East Germany too different and perhaps too cold for their tastes. Jagan pointed out that he had operated elevators in the United States from midnight to 8:00 A.M. and added that “young men needed to learn to be intrepid.”

3 British officials thought Jagan’s efforts to obtain aid from the Soviet bloc would hurt British Guiana’s image in the United States. On the other hand, as Patricia Hutchinson of the Foreign Office remarked, “there are a number of aid-recipient countries, India for instance, which still manage to obtain substantial American aid in spite of assistance from the Soviet Union.”

4Jagan and the PPP’s chief legislative goal for the first half of 1961 was the separation of church and state in education. As late as the mid-1950s, 269 of the 297 primary schools in the colony were church-affiliated schools. Hindu and Muslim children attended schools administered by Christian clergy. Indian teachers alleged that they were denied promotions. The Jagan government established state authority over fifty-one denominational schools. The measure sparked outbursts, protests, and charges of communism by Roman Catholic and Anglican bishops. Administrators and principals, who were primarily Afro-Guyanese Christians, feared the loss of their positions. Educational reform had the unfortunate effect of intensifying racial tensions in the colony. The Colonial Office did not express alarm, perhaps reasoning that the process of separating church and state began in eighteenth-century Europe.

5By 1961, the United Kingdom wanted to cut the imperial ties as quickly as possible. Governor Ralph Grey (1959-64) articulated British positions while richly fulfilling the role of the condescending colonialist. Sir Ralph told U.S. diplomats that his country “has fully accepted the fact that the days when it can run British Guiana are over and it would like to get out of the business of running the country as gracefully and honorably as possible.” In Grey’s opinion, British Guiana never amounted to much economically and lacked the natural potential to compete in international markets as an independent country. The colony “was hardly a good showpiece for what the ‘old imperialism’ either had accomplished or was capable of accomplishing.” Grey also found the Guyanese wanting, labeling them “children” in dispatches to the Colonial Office. Governor Renison’s expectation that the colonial subjects would mature with political responsibility had not come to pass. Grey judged “there has been time enough for the children to realize the increasing measure of responsibility they now have for their own destiny.” Unless they came “to grips with their own destiny,” the Guyanese would not be able to sustain their independence.

6 Some officials in London shared Grey’s patronizing views. Commonwealth Secretary Duncan Sandys exclaimed to Prime Minister Macmillan that “the sooner we get these people out of our hair the better.”

7Although Governor Grey constantly ridiculed the colonial subjects, he did not consider them an international menace. Grey never hesitated to tell London or Washington that Cheddi Jagan was not part of an international Communist conspiracy. He depicted Jagan as “a muddle-headed Marxist-Leninist socio-economist who dazes himself with hard work and too much turgid reading and many of his public utterances are arrant nonsense as well as being tediously dull.” He conceded Jagan was dedicated to the people of British Guiana. But his favorite word for the PPP leader was “impractical.” When he was not speculating on Janet Jagan’s marital life and romantic affairs, Grey spoke favorably of her as being, unlike her husband, “intelligent and practical.” Grey could not imagine that the Soviet Union would have any interest in the Jagans, the “muddlers” of the PPP, or insignificant British Guiana.

8 In part, Grey based his assessments of the Jagans and the PPP on the intelligence he received from the Special Branch. The Special Branch had thoroughly penetrated the PPP, receiving regular reports from agents. Governor Grey used colorful, often obnoxious language to describe British Guiana’s political milieu.

9 But his assessment of the role of communism in colonial life mirrored the judgments of his predecessors, Governors Savage and Renison.

Governor Grey became especially exasperated when U.S. officials spoke of a link between the colony and Castro’s Cuba. As he noted to the Colonial Office in early 1961, “I do not get very excited about all the Cuban business but it is perpetually in our local newspapers and the Americans are very hot about it.”

10 He investigated alarms sounded by U.S. officials. In February 1962, for example, U.S. Consul Everett Melby relayed intelligence that a Cuban vessel, the

Bahía de Santiago de Cuba, carrying fifty tons of arms, had docked in Georgetown’s harbor. Grey ordered his security personnel to board the vessel. They found secondhand printing machinery on board. The ship left Georgetown after loading the rice that British Guiana’s farmers had sold to Cuba. In another case, Cubans allegedly deposited an arms cache on the western coast of Venezuela, more than 1,000 miles from Georgetown. U.S. officials suggested this Cuban aggression threatened British Guiana. Grey responded, “Do people who send out these reports look at maps?”

11However harshly Governor Grey spoke of the Jagans and the PPP, he and his colleagues in the Colonial Office saved their severest criticism for Forbes Burnham and the PNC. They believed they could work with Cheddi Jagan and actually hoped that he would triumph in the August 1961 elections. As Colonial Undersecretary Hugh Fraser observed, Jagan was not a “serpentine” character who hid his intentions “but rather one who is too open and talks too much.”

12 By comparison, Burnham engendered a sense of foreboding among colonial officials. Grey dismissed Burnham as a “racist” who masked his radical political aims. The Colonial Office seconded Grey’s assessment, labeling Burnham as “irresponsible” and one who acted “like a madman rather than a politician.” It saw “Burnham’s irresponsible racist agitation” as having the “greatest potential for triggering serious violence during and after the election.”

13During the campaign that led to the 21 August 1961 elections, Forbes Burnham indeed called on his fellow Afro-Guyanese to vote their racial biases and fears. He warned that Jagan wanted to control the businesses, land, and shops of blacks. He referred to Janet Jagan as “that little lady from Chicago, an alien to our shores.” Jagan rejected such base appeals, albeit PPP faithful chanted the Hindi slogan “Apan Jaaht!” or “Vote for your own.” A relentless campaigner, the darkly handsome Jagan armed with his flashing smile and wavy hair made his campaign pitch in towns, like New Amsterdam, where blacks resided. He emphasized that progress, not domination by Indians, was the issue for Guyanese. He rejected religious intolerance, declining to associate with religious leaders who called on Hindus “to fight for their religion.” The PPP ran a slate that included fourteen Indians and twelve blacks, with eight blacks given safe seats. The PPP’s platform called for parliamentary democracy, freedom of religion, safeguards for private capital and investment, economic development, and a mixed economy based on the models of Ghana and India. Beyond his ideas, Jagan probably also impressed Guyanese, especially Indians, with the way he lived his life. As recounted by novelist V. S. Naipaul, who reported on the 1961 campaign, the Jagans lived in an “unpretentious one-floored wooden house standing, in the Guianese way, on tall stilts. Open and unprotected.” What distinguished their house was the packed book shelves and magazine rack, which included the

New Yorker.

14 As it had in 1953 and 1957, the PPP had another big election win in 1961, capturing 20 of the 35 legislative seats. Burnham’s PNC won 11 seats, and Peter D’Aguiar’s United Front (UF) won the remaining 4 seats. The UF appealed to affluent Guyanese and Christians angry over school issues. Two of the UF seats were in the interior where Amerindians, who were closely associated with Christian missionaries, lived. The popular vote broke down along racial and ethnic lines and was close. The PPP won 42.6 percent, the PNC won 41 percent, and the UF won 16.3 percent. The PPP could have increased its raw vote total somewhat, if it had vigorously contested all 35 seats. The traditional “first across the post” system of vote counting gave the PPP a clear majority in the legislature. The Colonial Office was satisfied with the election, and Governor Grey asked Jagan to be prime minister and to form a cabinet. Jagan presented a multiracial cabinet that did not include Janet Jagan. The Colonial Office expected that the Jagan government would lead the colony to independence and scheduled an independence conference for May 1962.

15 Forbes Burnham, however, dismissed the electoral results, ominously remarking to U.S. Consul Melby that the “PNC controls Georgetown, civil service, police, trade unions and could shut down the country overnight.” The bitter Burnham also warned the PNC faithful that, in the aftermath of the “Indian racial victory,” bumptious PPP members were boasting that blacks would be dispatched to the sugar fields “to cut cane and pull punt.”

16The John F. Kennedy administration tried to prevent Cheddi Jagan and the PPP’s August 1961 electoral victory. With the Cold War coming to the Western Hemisphere in the form of the Cuban Revolution, the Kennedy administration would accept only those Western Hemisphere governments that unequivocally denounced communism and assented to U.S. foreign policy positions. As a senator, John Kennedy had garnered international praise for his 1957 speech in which he defended nationalism and denounced French colonialism in Algeria. He also had called for increased economic aid for nonaligned nations like India. As president, he often stated, including to Cheddi Jagan and President João Goulart of Brazil (1961-64), that the United States judged a nation on whether it was politically independent in the international arena, not on whether the United States agreed with its internal political and economic philosophies. He also claimed that he did not object if nations traded with the Soviet bloc, as long as they avoided economic dependence on Communist nations. The president proudly noted that the United States granted foreign aid to Yugoslavia, an independent Communist nation. In reality, however, the president excluded Western Hemisphere nations from this cosmopolitan approach. His administration launched, for example, a destabilization campaign against President Goulart of Brazil because the Brazilian pursued independent domestic and international policies that seemingly had the potential of giving aid and comfort to the Communists.

17In the case of British Guiana, the president’s actions also belied his rhetoric about respecting nationalism. Kennedy saw Jagan and the PPP through the prism of revolutionary Cuba. The president had, in presidential aide Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.’s words, an “absolute determination” to prevent another Communist bridgehead in the Western Hemisphere.

18 The president and his closest advisers persuaded themselves that the Jagans were wolves in sheep’s clothing who engaged in democratic politics as means to an end. Once free of British colonial rule, they would openly embrace communism and ally with the Soviet Union. The United States would then be confronted with a “second Cuba” on the South American continent. As Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy saw it, what happened in British Guiana might determine the “future of South America.” Kennedy conceded that it was a “small country,” but Cuba was also small, and “it’s caused us a lot of trouble.”

19 Other administration officials saw historical parallels between Jagan and Castro. Deputy Under Secretary of State U. Alexis Johnson reminded British officials that “Castro had originally been presented as a reformer.” He added, “We do not intend to be taken in twice.” Secretary of State Dean Rusk agreed that, in view of “the prospect of Castroism in the Western Hemisphere,” the United States was not inclined to give Jagan the same benefit of doubt which was given two or three years ago to Castro himself.” President Kennedy also recalled the lessons of history. In a conversation with President Ramón Villeda Morales of Honduras, he observed that “experiences with Jagan, the Chinese, and Castro demonstrate that Communists frequently take over a Government in the guise of enlightened, democratic, revolutionary leaders, and not as Communists per se.”

20The historical parallels and lessons that the president and his advisers drew on were often lost on intelligence analysts. In March 1961, the intelligence community, led by the CIA, produced its first “Special National Intelligence Estimate” on British Guiana. The analysts surveyed the colony’s political scene and predicted that the PPP would likely gain a majority in the upcoming election. They could not predict what would follow. The analysts thought it unlikely that an independent state under Jagan “would proceed forthwith with an effort to establish an avowed Communist regime.” They were even uncertain about Jagan’s political leanings. Jagan never acknowledged being a Communist, “but his statements and actions over the years bear the marks of the indoctrination and advice the Communists have given him.” They referred to the “ineffectual” Forbes Burnham as “a negro and doctrinaire socialist.” The intelligence community’s most informed guess was that an independent Guyana would align itself at the United Nations “with Afro-Asian neutralism and anti-colonialism.” A Jagan government would be nationalistic, sympathetic to Cuba, and ready to establish political and economic ties with the Soviet bloc. Yet, Jagan wanted good relations with the West, because he needed economic aid from the United States and the United Kingdom.

21 However accurate and sophisticated these and subsequent national intelligence estimates were, they made little impression on the Kennedy administration and the successor Lyndon B. Johnson administration. Officials like Secretary Rusk actually took alarm from them, interpreting these cautious, restrained analyses as mandates for U.S. intervention in British Guiana. Cold warriors could not countenance a neutral nation in the traditional U.S. sphere of influence.

Within months of taking office, President Kennedy began plotting against Cheddi Jagan. On 5 April 1961, at a meeting in Washington, Kennedy briefly mentioned to Prime Minister Macmillan that the United States could not accept another Castro in the hemisphere and opposed Jagan leading an independent Guyana. The next day, Secretary Rusk reiterated U.S. concerns to Foreign Secretary Alexander Frederick Douglas (Lord) Home and other British officials. Rusk found the British baffled by the U.S. fear of Jagan. Ambassador Harold Caccia noted that “the Jagans provided the most responsible leadership in the country and they would be difficult to supplant.” The British declined suggestions to undermine democratic procedures and refused to give the United States permission to launch a covert operation to prevent a Jagan victory. Instead, the British asked the United States to consider using economic aid as a way of fostering moderate policies in British Guiana.

22 The Kennedy administration essentially ignored the British arguments. On 5 May 1961, shortly after the Bay of Pigs debacle, the president ruled at an NSC meeting that the “Task Force on Cuba would consider what can be done in cooperation with the British to forestall a Communist takeover” in British Guiana. The administration had implicitly tied Cheddi Jagan and British Guiana to Fidel Castro and Cuba. The administration made it U.S. policy “to aim at the downfall of Castro” and would organize thereafter a massive sabotage and terrorism campaign against Cuba code-named “Operation Mongoose.” The administration simultaneously ordered the veteran spy, Frank Wisner, who was stationed in London, to organize CIA activities in British Guiana.

23As had the Eisenhower administration, the Kennedy administration met with supporters of Burnham and Peter D’Aguiar. D’Aguiar himself met with Adolf A. Berle Jr., who was helping to plan the administration’s bold, new economic aid program for Latin America, the Alliance for Progress. D’Aguiar warned that the Jagans would deliver British Guiana “lock, stock, and barrel to the Communist camp.”

24 Jagan’s opponents asked for U.S. help. State Department officials made no direct commitment but asked the consulate in Georgetown if Jagan’s opponents needed financial assistance. The CIA likely passed money to conservative Christian groups, like the U.S.-based World Harvest Evangelism and the Christian Anti-Communist Crusade, who denounced the secularization of British Guiana’s schools. Dr. Lloyd Sweet of Miami and the World Harvest Evangelism assured State Department officers that God guided him in his fight against Communists like Jagan. D’Aguiar’s party also showed U.S. Information Service films with strong anticommunist and anti-Castro themes on Georgetown street corners.

25 This U.S. effort to shape the colony’s public opinion was modest compared to what would follow in British Guiana and in other South American countries. Jagan alleged in his memoirs that the Christian Anti-Communist Crusade spent $45,000 in 1961. In 1962, the CIA spent $5 million supporting anti-Goulart candidates in Brazil, and President Kennedy authorized the CIA to spend over $200,000 to support the Chilean Christian Democrats, the rivals of the Chilean Marxist Salvador Allende.

26In early August 1961, the administration made a final effort to prevent Jagan’s election. President Kennedy instructed his foreign policy team to concentrate on British Guiana. Secretary Rusk contacted Lord Home and reminded him that the United States judged that “Jagan and his American wife were very far to the left indeed and that his accession to power in British Guiana would be a most troublesome setback in this Hemisphere.” Rusk wanted the British to arrange a confused electoral result to lay the basis for a future election by taking some unspecified action in four or five legislative districts. Rusk also consciously tried to instigate a showdown between the Colonial Office and the Foreign Office. The secretary of state understood that the Colonial Office oversaw British Guiana, but he wanted Foreign Secretary Home to consider the “foreign policy ramifications of a Jagan victory.”

27 On 18 August 1961, in a “to Dean from Alex” reply, Home defended the principle of democratic electoral procedures and expressed guarded optimism about Cheddi Jagan. He predicted that, if the United States assisted the colony, “we think it by no means impossible that British Guiana may end up in a position not very different from that of India.” The foreign secretary also diplomatically pointed to the hypocrisy inherent in the U.S. position on colonialism, noting that it was “true over the wide field of our Colonial responsibilities, we have had to move faster than we would have liked.”

28 Rusk was unmoved by this British appeal to both his sense of justice and shame. On 26 August, he deplored the electoral results and called for a new round of Anglo-American discussions on the colony. Rusk reminded his friend Alex that he attached “importance to the covert side” in future courses of action.

29If there ever was a possibility of the United States working with Prime Minister Jagan, it occurred in September and October 1961. Colonial officials wished for “an ounce of sympathy” for Jagan, praying that the prime minister would make a good personal impression and win U.S. economic assistance, when he visited Washington and President Kennedy in late October. Governor Grey coached Jagan on how to sell himself to the U.S. public and the president. The governor fretted, however, that Jagan “may well get minced up at question time,” when he appeared on the Sunday television news show,

Meet the Press. Grey further worried that U.S. officials had lost perspective on the colony, equating British Guiana with the Soviet-American confrontation over Berlin.

30 U.S. Consul Everett Melby backed Grey’s argument that Jagan desired good relations with the United States. Within the administration, Presidential aide Arthur Schlesinger responded positively to British pleas for understanding of Jagan and peppered the president with memorandums about British Guiana. Schlesinger was part of the liberal, internationalist wing of the Democratic Party led by luminaries like Eleanor Roosevelt and Adlai Stevenson, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. In the weeks before the Bay of Pigs fiasco, Schlesinger had bluntly warned Kennedy that a U.S.-backed invasion of Cuba would remind international observers of the brutal Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. Ambassador Stevenson worried that the United States would “undermine our carefully nurtured position of anti-colonialism among the new nations of Asian and Africa” if it opposed independence for British Guiana.

31 Canada, both a neighbor of the United States and a member of the British Commonwealth, also recommended that the administration work with Jagan. Secretary Rusk had forwarded the March 1961 intelligence estimate to Ottawa, reasoning that the Canadians would conclude that a PPP victory would jeopardize the substantial Canadian private investments in bauxite mining. Canadian mining companies assured their government, however, that they had substantial confidence in the Jagan government. Canadian officials gave Jagan a warm welcome in October 1961 when he visited Ottawa.

32Most of President Kennedy’s advisers and supporters, however, unequivocally opposed a U.S. relationship with Jagan and the PPP. Secretary of State Rusk never wavered from his conviction that Jagan wanted to transform an independent Guyana into a Soviet satellite. Members of Congress agreed with Rusk. Senator Thomas Dodd of Connecticut led the assault against Jagan. Dodd, a leading member of the conservative, ferociously anticommunist wing of the Democratic Party, believed everything that Burnham and D’Aguiar told him about British Guiana. Dodd passed on to the administration documents, poorly forged by D’Aguiar’s minions, purporting to prove that Jagan was on the payroll of the Soviet Union. The State Department eventually received 113 congressional letters critical of a policy of working with Jagan. Only Senator George Aiken spoke up for economic aid for British Guiana. Unlike his colleagues, the Vermont Republican had visited the colony.

33 Congressional sentiment reflected constituent pressure. African American members of the Democratic National Committee recommended that the administration support “the Negro leader,” Forbes Burnham, who “is wholly committed to our cause.” The small Afro-Guyanese community in New York City also lobbied on behalf of Burnham and the PNC.

34 Most important, labor union officials pressed their long-held views that the Jagans aimed to destroy the free trade union movement. Labor unions had campaigned hard for John Kennedy in 1960. Robert Alexander of Rutgers University, who had served Jay Lovestone of the AFL-CIO and repeatedly attached the Communist label to the PPP, helped design the Alliance for Progress. William Howard McCabe, who used the cover of the Public Service International, an international affiliate of the AFL-CIO, and was a CIA agent, conducted a fact-finding mission to British Guiana in October/November 1961. McCabe called on the AFL-CIO to fight to save freedom in British Guiana. While in the colony, McCabe organized an antigovernment strike by the Commercial and Clerical Workers Union but kept his role hidden.

35In September 1961, President Kennedy approved a program that gave the appearance of a U.S. effort to accommodate the United Kingdom on British Guiana. When U.S. representatives went to London on 11 September to discuss British Guiana, they presented a dual-track policy. They promised British officials that Jagan would be given a friendly reception in the United States and offered economic assistance. An independent Guyana would be welcomed into the inter-American community. At the same time, the administration planned to develop a covert program to expose and destroy Communists in British Guiana, “including, if necessary, ‘the possibility of finding a substitute for Jagan himself, who could command East Indian support’.” As Schlesinger pointed out to Kennedy, the covert program had the obvious potential to conflict with the friendship policy.

36 The State Department highlighted that contradiction when it asked the Colonial Office to keep in mind the “possibility Jagan is Communist-controlled ‘sleeper’ who will move to establish a Castro or Communist regime upon independence.”

37 The “sleeper” allegation suggested that State Department officers had perhaps persuaded themselves that Jagan embodied the central character in

The Manchurian Candidate (1959), the Cold War political thriller by novelist Richard Condon. In any case, British officials emerged from the September 1961 Anglo-American meetings pleased that the United States had pledged to help British Guiana. They reluctantly agreed to joint intelligence gathering, but they refused to give the CIA permission to conduct covert operations in the colony. The British declined to accept the U.S. argument, as Ambassador to the United Kingdom David Bruce put it, that “various components of our program are parts of an inter-related package.”

38 Events would prove that the Kennedy administration would not be bound by the ban on covert activity.

Prime Minister Jagan’s talks in Washington in October 1961 with President Kennedy, Secretary Rusk, and other State Department officers seemingly went well. The State Department characterized Rusk’s conversation with Jagan as being conducted in “an atmosphere of warmth and cordiality.” Jagan thought Rusk “sympathetic and understanding” to his plans to help the rural poor and secularize education.

39 At the White House, Jagan emphasized to Kennedy that he believed in democracy, an independent judiciary, and independent civil service “in the British tradition.” He called U.S. assistance “a political necessity for him.” As Consul Melby had reported, Guyanese thought Jagan would come home with the “keys to Fort Knox.” Jagan had grandiose ideas of spending up to $250 million on economic development. He envisioned receiving $40 million from the United States, which, on a per capita basis, would be far more than the United States offered any Latin American country under the Alliance for Progress. As a rule, Kennedy never discussed specific sums of money with foreign leaders. The president assured Jagan, however, that the United States could work with nations that pursued independent foreign policies.

40 Jagan left Washington disappointed he had received only a vague promise of a $5 million aid package. Nonetheless, Jagan reported to Governor Grey that he thought he had done well politically and that he communicated especially well with Kennedy and Under Secretary of State Chester Bowles. The prime minister wondered, however, whether the U.S. Congress would appropriate funds for countries “that do not fit into the American socioeconomic pattern.”

41Cheddi Jagan misinterpreted his dignified audience with President Kennedy. As recounted by Schlesinger in his memoir of the Kennedy presidency,

A Thousand Days, the president had already decided he could not abide Jagan governing an independent Guyana. He had watched Jagan’s appearance on

Meet the Press.

42 As Governor Grey feared, Jagan suffered a public relations disaster. Broadcaster Lawrence E. Spivak assumed the role of the redbaiting Senator Joseph McCarthy. Spivak’s first question: “Are you or are you not pro-Communist.” Spivak thereafter conducted an inquisition, grilling Jagan on differences between communism, Marxism, and socialism and demanding that Jagan denounce the Soviet Union. Jagan gave his customary imprecise, rambling answers to what the British embassy in Washington called Spivak’s “character assassination.” Spivak had made Jagan look “evasive and insincere,” with television shots of Spivak “listening like a tightlipped and disbelieving schoolmaster to a shifty pupil.” Other members of the panel, like veteran

New York Times journalist Tad Szulc, treated Jagan with respect, asking questions about Jagan’s plans for socioeconomic development. The Canadian press also gave Jagan sympathetic treatment, responding positively to Jagan’s dream or fantasy of an independent Guyana joining both the Commonwealth and the Organization of American States and serving as a link between the Commonwealth, Latin America, and the United States.

43The

Meet the Press interview gave President Kennedy an excuse for rejecting Jagan; U.S. taxpayers would dislike aiding a politically suspect leader. Kennedy would have to think hard about overruling his secretary of state and angering supporters like conservative Democrats, African Americans, and labor union officials. But even if Jagan had impressed the U.S. public, the president would have spurned him. With its $20 billion Alliance for Progress, the “Marshall Plan for Latin America,” the United States proposed to build progressive, democratic, anticommunist societies throughout the region. In turn, the administration expected Latin American leaders to support U.S. foreign policies, and it insisted that they sever all ties with Communist Cuba. Presidential aide Richard Goodwin framed the issue squarely for Kennedy on 25 October 1961, the day Kennedy hosted Jagan. In August, Goodwin had attended the organizational conference, held in Punta del Este, Uruguay, for the Alliance for Progress. Goodwin had also had a lengthy exchange of views with Ché Guevara at Punta del Este. Goodwin warned the president that the United States could not permit neutralism in the Western Hemisphere. Jagan thought his country could “be an India, Ghana, or Yugoslavia.” If Jagan received aid, it would be “an open invitation for other Latin American politicos to take the same line.”

44 In the context of his relentless war against Fidel Castro, John Kennedy always took Goodwin’s type of advice. The president’s next task was to force Prime Minister Macmillan’s government to accept the U.S. campaign against Cheddi Jagan.

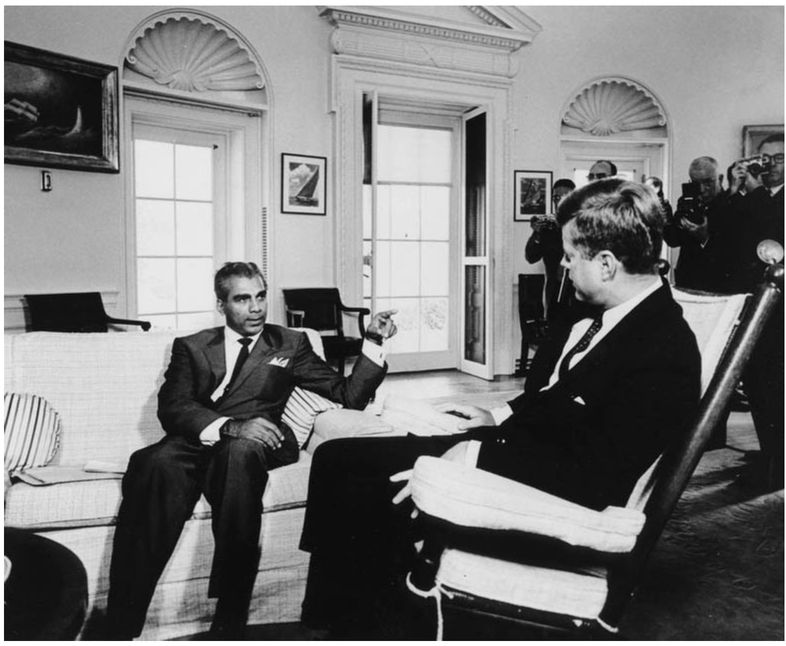

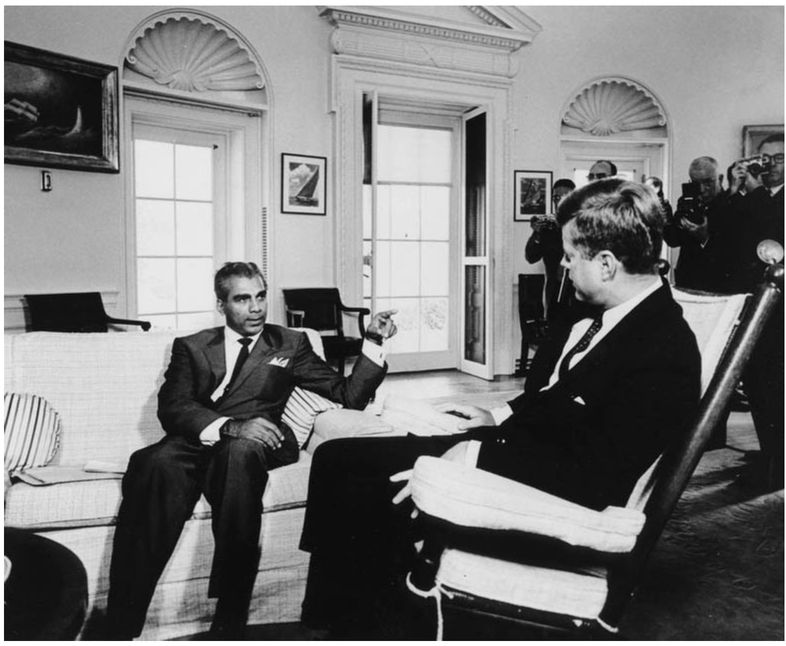

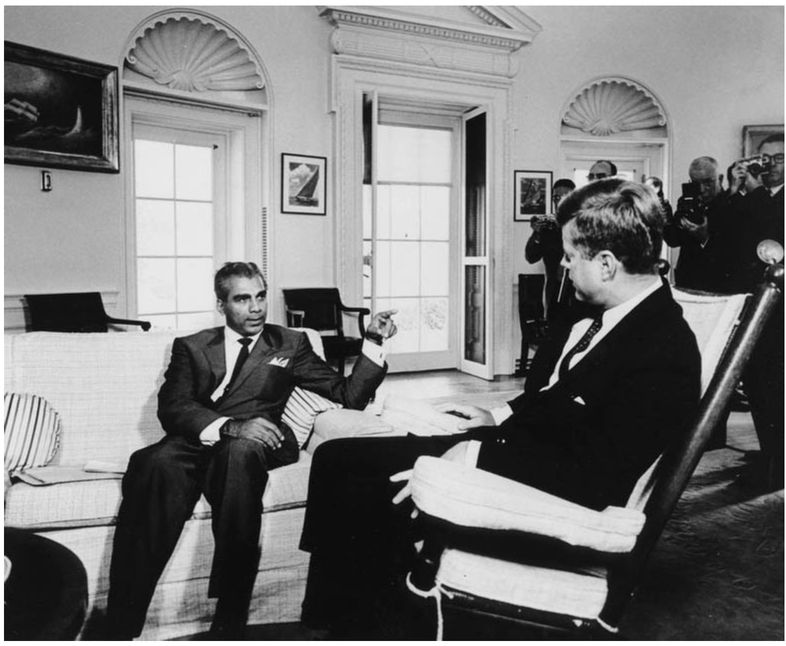

Prime Minister Cheddi Jagan and President John F. Kennedy at the White House, 25 October 1961. Photograph by Abbie Rowe, National Park Service, JFK Library.

GEORGETOWN, THE CAPITAL CITY of British Guiana, burned on 16 February 1962. Arsonists and bombers ignited “mammoth blazes” that consumed seven square blocks of the business section of Georgetown. Over fifty premises were destroyed by fire and another sixty were damaged and looted. Georgetown was especially susceptible to fire, because many of its important buildings were wood construction. Afro-Guyanese mobs attacked Indian merchants and looted their stores and stalls. With unemployment rates reaching 50 percent in Georgetown, crime was a major urban problem, with young blacks engaging in purse snatching and automobile theft. The young people proved ready to burn, loot, and murder when aroused by ruthless political leaders. Five people died and another forty were injured. Guyanese submitted claims to fire insurance companies of $6 million but damages amounted to more, because many merchants did not have riot insurance. Observers suggested damages totaled as much as one-sixth of British Guiana’s gross national product. The colony’s economy thereafter went into a steep decline. Surveying the damage, Governor Grey confessed to the Colonial Office that he was “sickened at its extent.” U.S. Consul Melby shared Grey’s dismay, lamenting that “whatever the immediate cause of the riots, they quickly took on an ugly racial tone in predominately African Georgetown.”

45Prime Minister Jagan’s opponents transformed a political debate into a political crisis in February 1962. Jagan proposed a budget based on the advice of Nicholas Kaldor, a Cambridge University economist who had been recommended to Jagan by the United Nations. Kaldor had previously advised governments in Ceylon, Ghana, and Mexico. In order to raise capital for roads and irrigation canals, the government would raise taxes on wealthy citizens and attach duties on nonessential imports. The government also devised a compulsory savings scheme, requiring wage earners earning as little as $60 a month to dedicate 10 percent of their wages to interest-bearing tax-free bonds redeemable in seven years. The Colonial Office accepted the rationale for Jagan’s budget, pointing out that British Guiana needed money, the United Kingdom “was strapped for money,” and the United States had refused to give a firm commitment of aid. London also knew that PPP leaders had tried and failed to obtain foreign aid from France, Italy, and West Germany. Both Iain Macleod and Reginald Maudling, the old and new colonial secretaries, dismissed allegations that the tax program was a Marxist program. The president of Booker Brothers defended the budget, calling it “a serious attempt by Government to get to grips with formidable economic problems.” The Colonial Office judged that Jagan was acting thoroughly within democratic procedures, although it thought he could have done a better political job preparing Guyanese for sacrifices.

46Forbes Burnham and Peter D’Aguiar opposed the budget by resorting to violence. They played on the legitimate fears of Guyanese, such as civil servants, who could not see how they could afford new deductions from their already meager wages. Both Burnham and D’Aguiar recognized they could not defeat the PPP democratically and that Cheddi Jagan would lead the colony to independence. They, along with union leader Richard Ishmael, sought to bring the government down in the streets. Ishmael had informed the AFL-CIO that the movement toward independence could be delayed by strikes and asked U.S. union representatives in British Guiana for guns and dynamite.

47 Burnham repeatedly boasted that he controlled the levers of power in Georgetown. Both Burnham and D’Aguiar organized huge mobs, made incendiary statements to the mobs, and then declined to stop their rampages. Both men were photographed brazenly shaking hands after leading an illegal march around government buildings. U.S. Consul Melby reported that Burnham “proved his skill at arousing Georgetown mobs.”

48 A subsequent Colonial Office judicial inquiry blamed the trio of Burnham, D’Aguiar, and Ishmael for the violence.

49 The Jagan government could not control the mobs, because the police force did not respond to his commands. Virtually all police officers were Afro-Guyanese, because Indians had historically been denied the chance to join security forces. At Jagan’s request, Governor Grey restored calm by deploying British troops in the colony and calling for reinforcements from Jamaica and the United Kingdom. Consul Melby opined that British troops probably saved Jagan’s life.

50 Jagan abandoned his budgetary proposals.

The CIA aided and abetted the rioters. The Kennedy administration had decided to generate chaos in the colony to force the Macmillan government to delay British Guiana’s independence. At a meeting in Bermuda in late December 1961, Lord Home stunned Rusk by informing him that an independence conference would take place in May 1962 and that British Guiana would gain its independence within a year. State Department officers repeatedly implored the British to delay independence and schedule new elections. They “pointed out that Jagan won the previous election by a very narrow popular majority and that precedents in other British colonies could undoubtedly be found to support the concept of new elections.” The British refused and, in any case, Consul Melby predicted that the PPP would likely strengthen its majority in a new election.

51 So frantic was the administration to see Jagan out of power that it began to ask about the state of his marriage. State Department officers in Washington instructed the consulate to check press rumors that the Jagans were contemplating a divorce. In December 1961, the U.S. embassy in London reported that Janet Jagan had moved to London with a Communist lover. Two months later, the embassy updated its gossip, reporting that Janet Jagan’s “amorous relationship” was over. Consul Melby had already dashed the State Department’s apparent hope that divorce would leave Cheddi Jagan directionless, noting Cheddi Jagan’s political support in British Guiana did not depend on his marriage to a white foreigner.

52With its diplomatic efforts rejected, the administration turned to violence. It infiltrated CIA operatives into British Guiana in imaginative ways. On 12 January 1962 President Kennedy authorized the expansion of technical assistance to British Guiana to a level of $1.5 million and agreed that U.S. aid officials should go to the colony to study the feasibility of the $5 million aid package. Kennedy also informed Fowler Hamilton, the administrator for the Agency of International Development, that “I am also requesting immediate action to intensify our observations of political developments in British Guiana.” As Hamilton subsequently explained, what Kennedy signaled in the words “observations of political developments” was that the technical assistance and study groups should include CIA people.

53 On 18 January, the administration raised the status of its representation in Georgetown from consulate to consulate general. The diplomatic staff would thereby be increased, providing increased opportunities for CIA agents to put on the cloak of diplomatic cover. The administration also intensified its contacts with Jagan’s political opponents, trade union officials in British Guiana, and the AFL-CIO.

After the fires of 16 February, Jagan publicly raised the issue of CIA intervention and remarked to Consul Melby “that he realized the U.S. government worked in various ways.” Administration officials categorically denied any role in the riots, with the State Department responding that it was “astonished” by Jagan’s “accusations and remarks.”

54 In response to a direct question from Colonial Secretary Maudling, Arthur Schlesinger replied that it was “inconceivable” that the CIA had stimulated the racial riots.

55 Union officials William Howard McCabe and Ernest Lee, the son-in-law of AFL-CIO President George Meany, assured Governor Grey that they had been in British Guiana for legitimate purposes. They added that they had rejected Richard Ishmael’s request for guns and dynamite. Lee stated that he intended to raise money for the union workers of British Guiana who had lost their jobs in the aftermath of the riots.

56The CIA has claimed that it destroyed its records on British Guiana. U.S. government censors have withheld key documents. Tim Weiner, a correspondent for the

New York Times who specializes in declassification issues, wrote in 1994 that government officials informed him that “still classified documents depict a direct order from the President to unseat Dr. Jagan.” Weiner continued, “The Jagan papers are a rare smoking gun: a clear written record without veiled words or plausible denials, of a President’s command to depose a Prime Minister.”

57 Although the prosecuting historian cannot wave that proverbial smoking gun in front of a jury, the Kennedy administration would need the skills of a legendary lawyer like Clarence Darrow or F. Lee Bailey to explain away in a court of law the evidence that the Kennedy administration encouraged and financed the attacks on the Jagan government. Two former CIA agents, Philip Agee and Joseph Burkholder Smith, have written of the CIA’s involvement. Burkholder worked with associates of Forbes Burnham in February 1962.

58 Numerous sources have identified McCabe as a CIA agent, working under the cover of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees and its international affiliate, the Public Service International. McCabe arrived in British Guiana in the midst of the riots as a stowaway on an airplane carrying a blood bank from Surinam.

59 Since 1990, Arthur Schlesinger has repeatedly decried the CIA intervention in British Guiana.

60 Colonial officials, such as Undersecretary Hugh Fraser, similarly denounced the CIA intervention.

61 The administration’s brazen words and actions immediately after the riots further incriminated them. On 20 February 1962, even as Georgetown smoldered, President Kennedy expressed to the United Kingdom’s ambassador to the United States, David Ormsby-Gore, his “unhappiness” over British Guiana and his “regret” that Governor Grey and London “had moved so quickly in [a] manner which had [the] effect of shoring up [a] tottering Jagan regime.”

62 Both the president and State Department officials also promptly called on the British to see the riots as a reason for delaying independence and scheduling new elections. One State Department officer went so far as to claim that the riots were “a spontaneous outburst of democratic opinion, a la Hungary, against Jagan.”

63 No U.S. official, other than Consul Melby, expressed regret that racial warfare had broken out in British Guiana.

In case the United Kingdom officials could still not read U.S. intentions, Secretary of State Dean Rusk spelled it out for them in a message to Lord Home on 19 February 1962. Rusk informed the British foreign secretary that “it is not possible for us to put up with an independent British Guiana under Jagan.” The secretary darkly noted that the February riots resembled “the events of 1953.” The colony, Anglo-American harmony, and the inter-American system would all face “disaster” if Jagan continued in office. Rusk called for “remedial steps” leading to new elections. Rusk’s virtual ultimatum to the United Kingdom flowed directly from the advice he had received the day before from his subordinate, William R. Tyler of the European Division. Tyler recommend a “go for broke” policy to unseat Jagan. He further suggested keeping the February demonstrations going by sending money through third countries and the labor movement. Tyler thought, however, that the United States should counsel Jagan’s political opposition against violence.

64 On 8 March 1962 President Kennedy partially qualified Rusk and Tyler’s demands when he issued National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) No. 135. The memorandum noted that “no final decision” would be taken on British Guiana until Rusk met with Lord Home and British officials had the chance to conduct an “on-the-spot survey” of British Guiana. But the memorandum emphasized that the United States needed to explore ways to persuade the British to delay independence and schedule new elections.

65A range of emotions characterized the first reactions of British officials in London and Georgetown to Rusk’s demand that Guyanese be denied their democratic rights. Prime Minister Macmillan told Home that he read Rusk’s letter with “amazement” and found some of Rusk’s phrases “incredible.” The prime minister marveled, “How can the Americans continue to attack us in the United Nations on colonialism and then use expressions like these which are not colonialism but pure Machiavellianism.”

66 In his sarcastic reply to Rusk of 26 February 1962, Lord Home reminded the secretary of state of the historic U.S. role as “the first crusader and prime mover in urging colonial emancipation.” He also wondered how expressions such as “Jagan should not accede to power again” could be reconciled with democratic processes.

67 Colonial Office leaders, Iain Macleod and Reginald Maudling, tried reason on Arthur Schlesinger. Macleod, who did the talking for Maudling, rejected the charge of “Communist” that the United States leveled against Jagan. Instead, the former colonial secretary depicted Jagan as “a naïve, London School of Economics Marxist filled with charm, personal honesty, and juvenile nationalism.” He further asserted that if he “had to make the choice between Jagan and Burnham as head of my country I would choose Jagan any day of the week.”

68 Governor Grey, on the other hand, vented his frustration, bitterly complaining to a State Department officer visiting Georgetown that Washington had “offered no solutions other than to say no.” John Hennings, who served as the Colonial Office’s attaché in the embassy in Washington, contributed to the debate by initially labeling Rusk’s message as a “somewhat saucy letter.” He later decided that Rusk’s letter merited the term “impertinent.”

69Secretary of State Rusk was taken back by the United Kingdom’s reaction and asked President Kennedy to write to Macmillan.

70 The president first asked Hugh Fraser to stop in Washington for a meeting. The Undersecretary of State for the Colonies went to Georgetown in early March to assess the colony’s political milieu and survey the destruction. Fraser gave his all for queen and country during the more than three hours he spent with Kennedy. The president conducted ninety minutes of the meeting in a swimming pool heated to 92 degrees. Whereas the heat presumably soothed the president’s troublesome back, it left Fraser with an “exhausting experience.” Fraser emphasized that “racialism” between blacks and Indians was the central problem in British Guiana. He blamed Forbes Burnham and Peter D’Aguiar for exacerbating racial tensions. Fraser further suggested in his meetings with the president and other U.S. officials, including CIA Director John A. McCone, that the United States confused Jagan’s nationalism with international Communism. He hoped that he “made it clear that a line can be drawn between these types of international communists and what I would call the anti-colonial type of communist which I pointed out to them Jefferson might well have been if the communist manifesto had been written in 1748 instead of 100 years later.” In any case, Fraser ridiculed the idea that an independent Guyana would serve as a base for Communist expansion in the Western Hemisphere. The colony was a “mudbank,” surrounded by forests and mountains and without natural communications with Latin America. Finally, Fraser reiterated the British position that the United States could orient Cheddi Jagan toward the West with economic development assistance.

71Fraser’s mission to Washington failed, in the short term, to reduce the Anglo-American tension over British Guiana. Drawing an analogy between British Guiana and the American Revolution had not allayed U.S. concerns over Jagan. And British officials understandably resented the U.S. intervention in their colony. The Kennedy administration had violated the September 1961 agreement not to conduct covert operations in British Guiana. Prime Minister Macmillan or perhaps one of his aides placed two large exclamation points on the dispatch from Fraser, in which Fraser reported that CIA Director McCone told him that the CIA had taken no actions in British Guiana. Nonetheless, the Macmillan government realized it could not readily dismiss the U.S. position. Kennedy had given Fraser an extraordinary amount of presidential time. As Fraser concluded, that fact “makes it clear that the problem of B.G. in American eyes is regarded as one of critical importance.”

72

TWO MONTHS AFTER Hugh Fraser’s trip to Washington, Prime Minister Macmillan made the conceptual decision to accommodate the United States by delaying independence and finding a scheme to deprive Cheddi Jagan and the PPP of power. The prime minister’s decision came following Foreign Secretary Home’s meeting with Rusk in Geneva in late March 1962 and his own conference with Kennedy in Washington in late April. As Macmillan noted to adviser Sir Norman Brook, discussions with the U.S. officials had persuaded him that the United States attached “great importance” to the colony. He interpreted the U.S. concern as being “moved by internal political considerations as much as by a genuine fear of communism.” Nonetheless, the United Kingdom’s interests were served by cooperation with the United States. Macmillan further reasoned that “in the future the Americans will have to carry the burden of British Guiana and so it is only fair that they should have a chance in shaping its future.” On 30 May 1962, Macmillan wrote to President Kennedy, informing him he would postpone the independence conference and also try to persuade the political leaders of British Guiana to hold another election before independence.

73The prime minister’s decision to permit the United States to have its way in a British colony flowed from multiple sources. Somewhat to Macmillan’s surprise, he and Kennedy had become friends. Despite their obvious differences in age and experience, the two leaders found that they communicated well, that they shared similar insights on life and laughed at the same things. Kennedy once most famously shared with Macmillan his discovery that if he did not have sexual relations with a woman every three days that he would develop a terrible headache. The United Kingdom’s representative in Washington, Ambassador David Ormsby-Gore, facilitated communication between the two men. The president asked the British to appoint Ormsby-Gore, a Kennedy family friend, to the position. Ambassador Ormsby-Gore and his family frequently socialized with the president and his wife on weekends, including at the family compound at Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. Ormsby-Gore also had the privilege of easy access to the Oval Office.

74Beyond personal ties, the prime minister made it a fundamental principle of his foreign policy to work closely with the United States. Macmillan had drawn many lessons from the Suez debacle. He believed that his country’s wealth and power and its historical contributions to world civilization entitled it to a major say in international affairs. But Macmillan had learned from the Suez Crisis that the only way that the United Kingdom could pursue its foreign policy aims would be as the principal ally of the United States. Macmillan thought that he had created an “interdependent” relationship with the United States. President Kennedy also characterized the Anglo-American relationship as an interdependent one. The countries shared a common language and cultural tradition and had been wartime allies. But as historian Nigel J. Ashton has instructed, the two leaders differed on their interpretations of interdependence. Kennedy believed that he should consult with the British on major issues. For example, Ormsby-Gore became the first foreigner with whom Kennedy shared information about Soviet missiles in Cuba. The president also conferred with Macmillan throughout the Cuban Missile Crisis. But Kennedy never considered himself bound to take Macmillan’s advice on the missile crisis or any other foreign policy issue, including the future of British Guiana. Macmillan desired, however, for the Anglo-American relationship to mean a partnership of equals. When conflicts arose with Washington, the prime minister always had to weigh the specific issue against his larger goal of a harmonious relationship with the United States. To be sure, the prime minister occasionally defied U.S. leaders. He refused to join the trade embargo against Cuba, for example, because he knew that his country’s economic security depended on expanding trade.

75Bureaucratic and domestic politics also pushed Macmillan toward accepting the U.S. position on British Guiana. Consistent with its basic mission, the Foreign Office worked to promote good relations with the United States. British diplomats further believed that the Colonial Office failed to appreciate the nuances of international affairs. Foreign officers wrote of their “awkward” role mediating between the State Department and the Colonial Office and blamed the Colonial Office for not accepting that the United States had legitimate regional security concerns. Philip de Zulueta, a close adviser of Macmillan, agreed, telling the prime minister that “the Colonial Office still treats the place as if it were Africa or Asia whereas it is in the U.S. backyard and politically very important to the Administration with the midterm elections coming in the autumn.”

76 The Macmillan government also did not want to spend scare public funds keeping troops in a colony the British considered difficult and worthless. British officials calculated that British Guiana cost $7 million annually and that the bill would rise to $20 million if London reimposed direct rule.

77Although Prime Minister Macmillan signaled to President Kennedy in May 1962 that he would follow the U.S. lead on British Guiana, it would take him more than a year to execute the anti-Jagan policy. British Guiana became a matter of serious debate within the United Kingdom. Government officials, especially in the Colonial Office, naturally resented the U.S. meddling. Moreover, many genuinely wanted democracy to take hold in British Guiana. Whereas they had mixed opinions about Cheddi Jagan, the British never wavered in their judgment that Peter D’Aguiar was irresponsible and that Forbes Burnham was a demagogue and a racist. Officials constantly dreaded that another racial conflagration would erupt in the colony. Domestic developments may have led the British to think hard about racial relations. During the 1950s, the population of West Indians and Africans in England had increased, mainly through immigration, by 450 percent. Racial tensions arose in major urban areas like London and Manchester.

78 The Macmillan government also had to consider the views of important former colonial possessions like India and Pakistan that would take note of the British sacrificing the Hindus and Muslims of British Guiana on the altar of Anglo-American amity. The prime minister could further count on its Labour opponents seizing on any appearance of kowtowing to the United States. Some element of calculation also went into Macmillan’s delay. If he appeased the United States on British Guiana, he expected U.S. help on a knotty issue like the Congo or Southern Rhodesia.

While the British debated, the Kennedy administration readied itself for another election in British Guiana. In his 30 May letter to Kennedy, Macmillan had observed that the Western nations should generously support a new government, even if Dr. Jagan and the PPP once again won another election. The administration told itself, however, that the PPP could not be allowed to win a new election. As Dean Rusk reminded the president, the United States needed to base its policy “on the premise that, once independent, Cheddi Jagan will establish a ‘Marxist’ regime in British Guiana and associate his country with the Soviet Bloc to a degree unacceptable to us for a state in the Western Hemisphere.” Rusk’s 12 July 1962 memorandum to Kennedy included a plan for the CIA to manipulate the election. In the previous month, the Special Group, the administration’s select committee that oversaw counterinsurgency activities, had received a six-page paper on British Guiana. The president also authorized Richard Helms, the CIA’s deputy director of planning, to confer with British counterparts. The planning for a covert operation made Arthur Schlesinger “nervous.” The presidential aide had abandoned his personal campaign to persuade the administration to work with Jagan. He now agreed “there is no future in Jagan,” although he also concluded, after a trip to British Guiana, that the colony “would be worse off with Burnham than with Jagan.” Schlesinger also worried about the issue raised by National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy. Bundy noted that “it is unproven that CIA knows how to manipulate an election in British Guiana without a backfire.”

79

DESPITE THE MISGIVINGS of aides, President Kennedy pushed the anti-Jagan policy forward. Ambassador Ormsby-Gore recalled that the president, from the summer of 1962 on, made it “very clear” to him that Jagan’s rule in British Guiana “was unacceptable” to the United States.

80 On 18 August 1962, Kennedy met with CIA Director John A. McCone to review the covert campaign against Cheddi Jagan. The president secretly tape recorded the meeting. McCone noted that CIA agent Frank Wisner reported that the British had wanted to talk about alternatives to Jagan but not establish a policy. But McCone and Secretary of State Rusk had sent Assistant Secretary of State William C. Burdett to London to drive “the thing further along than I think the British expected.” As a result, the British now agreed that “the Jagan government is undesirable and Communist oriented.” Nearly four minutes of the tape recording remain classified. The meeting concluded with McCone leaving with Kennedy a “doctrine paper” on U.S. covert activities in eleven countries. McCone observed that the paper was highly classified, “because it tells all about the dirty tricks and we don’t want to circulate it.” National Security Adviser Bundy characterized the paper as “a marvelous collection or dictionary of your crimes.” Laughter followed Bundy’s quip.

81As it plotted against Cheddi Jagan, the Kennedy administration embraced Forbes Burnham. In March 1962, Burdett had conferred with Burnham in Georgetown. Burnham asked the United States to bypass the government and provide economic assistance directly to the people. Burnham further asked for U.S. financial support and for weapons. The United States should also persuade the United Kingdom to establish an electoral system based on proportional representation. He threatened a civil war, with the PNC having “to fight to defend itself,” if the new electoral system was not established.

82 Burnham would eventually receive all he asked. Upon Burdett’s recommendation, the administration hosted Burnham in Washington in May 1962 and again in September. Burnham made a good impression on presidential aides and State Department officers. U.S. officials thought Burnham “presented PNC case in restrained manner typical of [a] British barrister.” Indeed, the handsome Burnham never failed to impress with his dignified bearing and his impeccable British manners. Burnham’s case included charging the Jagans as “thoroughgoing Communists,” alleging that they received instructions from the British Communist Party in 1955, and warning that Cuba was sending arms to British Guiana. He emphasized that the PNC respected private enterprise. While in Washington, Burnham also met with Senator Thomas Dodd. Burnham returned with $100,000 in student scholarships, providing tangible evidence to Guyanese that Forbes Burnham, not Cheddi Jagan, could secure U.S. assistance.

83 Governor Grey noticed that Burnham had become cocky, boasting that he had the unlisted telephone numbers of presidential aides Schlesinger and Richard Goodwin and that he would now only speak to assistant secretaries or higher in the State Department.

84 In making Burnham the U.S. man in Georgetown, the Kennedy administration had to overlook the assessments of the intelligence community. In the 11 April 1962 National Intelligence Estimate of British Guiana, intelligence analysts wrote that “Burnham has a reputation for opportunism and venality.” They added: “His racist point of view, so evident in the past, forebodes instability and conflict during any administration under his leadership.”

85While in Washington, Burnham met with the leadership of the AFL-CIO. Indeed, among Burnham’s boasts to Governor Grey, was the assertion that “a word to George Meany” would open important doors for him. Meany attended a luncheon for Burnham hosted by Serafino Romualdi. Labor officials also introduced Burnham around the United States, having him meet, for example, union representatives of the meat cutters in Chicago. The meat cutters promised to send men to train butchers in British Guiana. Andrew McLellan of the AFL-CIO’s International Affairs Department began working with Richard Ishmael and CIA agent McCabe, promoting the issue of proportional representation to the Colonial Office. U.S. union officials also lobbied Kennedy administration officials, like Vice President Johnson, attesting that Burnham and the PNC “represent the democratic movement in British Guiana.”

86The AFL-CIO also managed to increase U.S. influence in British Guiana while simultaneously enhancing Burnham’s stature. In late 1961, the union established the American Institute of Free Labor Development (AIFLD). Romualdi served as president of the institute, and William Doherty Jr. became its chief operating officer. Doherty was the son of William Doherty, a union official who became the U.S. ambassador to Jamaica, which gained its independence in 1962. AIFLD’s mission was to promote business unionism and combat any perceived “Castro-Communist” influence in the labor movement in Latin America. Between 1962 and 1967, the AIFLD received $15.4 million—89 percent of its budget—from Alliance for Progress funds. Contributions from U.S. corporations and labor unions made up the rest of the AIFLD’s budget. In the period from 1961 to 1963, the AIFLD also reportedly received $1 million from the CIA through conduits like the Gotham, J. M. Kaplan, and Michigan Funds. Emissaries from the AIFLD were especially active in Brazil, training Brazilian unionists to organize strikes and demonstrations against the government of João Goulart.

87 In British Guiana, the AIFLD proposed building over 2,000 low-cost housing units for postal and government employees who belonged to a union led by Andrew Jackson. Jackson supported Burnham and the PNC. In 1962, the AIFLD also brought six Guyanese unionists to Washington for the AIFLD’s first class on leadership training. The six returned to British Guiana and helped organize a massive, violent strike against the Jagan government in 1963. The six unionists remained on the AIFLD’s payroll during the strike.

88If the Macmillan government had chosen to reject the U.S. demands and defend democracy in British Guiana, it could have cited international support for its position. Foreign corporations and governments argued that the United States had badly misjudged the political culture of the colony. The two major foreign investors in British Guiana, British sugar interests and Canadian mining operators, considered Jagan the best option for the country’s future. Company representatives variously referred to Jagan as a “Christian Communist” and the “natural leader” of his nation. Both British and Canadian businessmen challenged the premise that political developments in British Guiana would have an impact in the Western Hemisphere.

89 Israel lobbied both the United Kingdom and the United States on behalf of Jagan, who had journeyed to Israel at the end of 1961. Israeli Foreign Minister Golda Meir told Foreign Secretary Home that “it was worth talking a risk and helping Jagan.” Meir worried that, if the West spurned Jagan, extremists in the PPP would push Jagan toward the Communist bloc. Israeli diplomats in Latin America delivered the same message to State Department officials. The Israeli ambassador to Venezuela thought Jagan a confused thinker but one who adhered to the rule of law and favored the West. Drawing on his own experiences in Israel’s struggle for independence, Ambassador Arie Oron observed that “Dr. Jagan does not appear to think like a real revolutionary.” Israel contemplated helping British Guiana train a local militia. The Kennedy administration politely but firmly rejected the Israeli advice, implying that Israel did not understand the politics of British Guiana. The State Department warned that if Israel aided Jagan it “would be regarded by [the] U.S. public as strengthening militarily a regime which has shown [a] consistent predilection for communism.”

90 Succumbing to U.S. pressure, Israel dropped all thoughts of aiding Jagan and British Guiana.

The Macmillan government similarly acceded to U.S. wishes, delivering on its commitment to undermine Cheddi Jagan. In late October 1962, the Colonial Office hosted a conference in London on British Guiana’s future. The conference had been scheduled for May and was originally designed to set a date for the colony’s independence. In fact, the conference was part of the Anglo-American plot against Jagan. Duncan Sandys, who now held the joint position of secretary of state for Commonwealth and colonies, presided over the conference. Sandys had opposed the progressive colonial policies of MacLeod and Maulding. Within the Macmillan cabinet, Sandys had earned the reputation as a “hatchet-man,” prepared to do Macmillan’s unpleasant tasks.

91 Sandys later told a Macmillan biographer that the prime minister made it clear to him that the Anglo-American relationship mattered more than the future of British Guiana.

92 On 10 September 1962, Sandys informed the prime minister of his scheme. The conference would not focus on independence, as Jagan had hoped. Instead, Sandys would allow the conference to breakdown over the issue of proportional representation. The colony’s political parties would continue squabbling at home, with no resolution. After a time, Sandys would call for a referendum on proportional representation, expecting that supporters of Forbes Burnham and Peter D’Aguiar would be able to muster 50 percent support for it. Sandys would then schedule new elections followed by an independence conference. Macmillan approved Sandys’s intrigue and authorized Ambassador Ormsby-Gore to inform his friend President Kennedy. Ormsby-Gore’s instructions included the caution to “please impress upon the President that no one at all knows of this plan and that it would be quite disastrous if it leaked out.”

93The conference on British Guiana, which lasted from 23 October to 6 November 1962 and took place in the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis, followed the course that Duncan Sandys had plotted. The parties deadlocked over the need for proportional representation. Jagan stressed the multiracial aims of his party and pointed to the PPP’s multiracial support. He argued that British Guiana deserved the same electoral system that existed in the United Kingdom and throughout the Commonwealth. Burnham countered that politics in British Guiana was strictly on a racial basis, with the PNC being an African party and the PPP being a party of Indians. D’Aguiar also called for proportional representation, although he devoted his time to charging, without proof, that the Soviet Union financed the PPP. At the end of the conference, Sandys announced that the United Kingdom might have to consider imposing a solution if the parties could not reach an agreement in the future. Knowing he had the solid support of the Kennedy administration and the U.S. labor movement, Burnham predictably rebuffed Jagan’s subsequent compromise proposals.

94 With its economy in ruins and its political system undermined, British Guiana was now, in the judgment of the Colonial Office, “in a parlous state.”

95 New waves of racial violence would engulf the colony in 1963 and 1964.

BY THE END OF 1962, the Kennedy administration had gone a long away toward accomplishing the U.S. goal of destabilizing the Jagan government. It had damaged the colony’s economy with the February 1962 strikes. It had also helped create a political climate of fear and tension between Indians and blacks. The administration had further found a Guyanese political leader who would seemingly do the U.S. bidding. What the administration needed was to ensure that the United Kingdom not waver from its pledge to remove the Jagan government from office. It would take two more years of covert intervention in British Guiana and constant U.S. pressure on the United Kingdom for the United States to achieve the dubious distinction of putting Forbes Burnham and the PNC into power.