CHAPTER FIVE

GUYANA, 1965-1969

During the period from 1965 to 1969, the United States achieved its enduring and immediate foreign policy goals for British Guiana. The United States traditionally favored national self-determination and opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. On 26 May 1966, the British colony in South America became the independent nation of Guyana. The U.S. man in Georgetown, Forbes Burnham, presided over the independence ceremonies. The United States had effectively deprived Cheddi Jagan and his party of any meaningful political role in Guyana. But the United States customarily promoted democratic procedures and liberal economic policies. It now preached the virtues of racial equality both at home and abroad. In showering Burnham with praise and economic assistance, the Lyndon Johnson administration aided a political figure who trampled on democratic procedures, plundered the nation, and denied Indians their basic political and human rights. After 1969, Burnham also transformed his nation into a bizarre state aligned with violent, radical movements. The people of Guyana paid a terrible price for the Cold War victory of the United States.

THE LYNDON JOHNSON ADMINISTRATION moved rapidly to bolster the new government of Forbes Burnham and Peter D’Aguiar, which took power in mid-December 1964. On 18 December, the administration proposed that an Anglo-American study team immediately go to British Guiana. Prime Minister Harold Wilson, wishing to maintain his options, opposed the idea, but the British soon thereafter permitted an officer from the U.S. Agency for International Development into the colony.1 The United States made good on the promise frequently given by Secretary of State Dean Rusk that the United States would generously aid the colony, once Jagan exited the political scene. In 1965, the United States provided $12.3 million, of which the first $5 million was in the form of a direct grant. The grant was unusual, for under the Alliance for Progress, the United States gave low-interest loans to Latin American nations. Only the poorest countries, Haiti and Paraguay, received grants in 1965. The United States dedicated the initial grant to road building, airport improvement, and sea defenses. Construction began on projects that the Eisenhower administration had initially promised to help build. Over the next three years, the United States provided an additional $25 million to the coalition government. By comparison, the United States had provided a total of less than $5 million in economic assistance from 1957 to 1964, the Jagan years. The United Kingdom supplemented the U.S. efforts, offering about $5 million in development assistance in 1965.

2

U.S. officials bluntly informed officers in both the Colonial Office and Foreign Office that the U.S. aid was conditioned on keeping Jagan out of power. As William Tyler of the State Department put it, the United States “would not be able to swallow such a coalition or help a government in which Jagan was a member.” In the immediate aftermath of the election, the Colonial Office continued to believe that a rapprochement between Jagan and Burnham could foster racial harmony in British Guiana. U.S. officials rejected the argument, holding that Jagan’s past record did not justify the assumption that racial harmony could be achieved through a rapprochement. Instead, they urged that Burnham be encouraged to appoint Indians to government and that U.S. aid be directed at helping rural Indians. Contrary to the results of the 1964 election, they further argued that an alternative Indian political party could succeed in the future.

3 The British did not accept U.S. reasoning, but officials, especially in the Foreign Office, wanted U.S. money. As one British diplomat noted, U.S. aid “will support Dr. Jagan’s contention that he has been deprived of office as a result of American pressures and that Mr. Burnham is a stooge of imperialists. On the other hand, there is a great deal that needs to be done in British Guiana, and we cannot afford to look a gift horse in the mouth.” The Foreign Office became so convinced of the need to conciliate the United States that it actually passed to the State Department memorandums by career officers in the Colonial Office who opposed U.S. policies in British Guiana.

4Dissenters in the Colonial Office undoubtedly would have liked access to U.S. documents. In January 1965, the CIA Office of National Estimates issued a special study, “Prospects for British Guiana.” It found that “the outlook for British Guiana remains bleak.” The polarization of Guyanese politics along racial lines had not diminished. Further racial clashes were “probable.” The intelligence analysts further took note that Burnham had appointed two ministers to his cabinet who had a history of racial militancy. Indians also resented that blacks continued to control the police force and the civil service.

5 The Johnson administration did not share such deep forebodings with the British. Anticommunist fears triumphed over racial concerns. The administration reminded British diplomats stationed in Washington that Burnham “may not be the ideal Premier but he is the only present alternative to Jagan and the PPP.” William Tyler addressed the concerns of Cecil King, publisher of the

Mirror, a London daily, about Burnham. The United States “was under no illusions” about Guyanese politicians. King might be right that Jagan was “simply a bewildered dentist.” Nonetheless, the U.S. legislators and citizens regarded Jagan as being vulnerable to Communist subversion and would deny economic assistance to any government that included him.

6As promised, the U.S. urged moderation upon Burnham. In 1965, with its money flowing into British Guiana, the United States essentially pushed the United Kingdom out of its colony. Consul General Delmar Carlson, described as a “ball of fire” by his superiors, dropped his initial distaste for Guyanese politicians and became a personal advisor to Burnham and D’Aguiar. Carlson essentially replaced Governor Luyt as the source of colonial authority, although he consulted with Luyt twice a week. Carlson defined his mission as “making Burnham a success and Jagan a failure,” which required “continued U.S. influence and manipulation.” Carlson urged Burnham to work with D’Aguiar and to issue conciliatory statements on race relations. When, in April 1965, D’Aguiar threatened to quit the coalition in a dispute over budgetary matters, Carlson interceded, warning that a collapse of the government would hand British Guiana to Jagan on a “silver platter.” He flattered the conservative D’Aguiar, congratulating him on saving the colony from communism.

7 Carlson also planned to have Burnham travel to Washington in May 1965 and meet President Johnson. Secretary Rusk and National Security Adviser Bundy planned an impressive ceremony for Burnham “as a factor in a process which we hope will protect us from the tragedy of another serious Communist threat in the Hemisphere.”

8 Domestic political uncertainties kept Burnham from making the visit in 1965. In turn, Burnham tried to please, acceding to U.S. demands on the international front. He severed ties with Cuba, including the rice trade, and agreed not to have contact with the Soviet Union. In a midyear review, Consul Carlson happily reported that Burnham was “doing better than expected” and was “amenable to U.S. influ-ence.” Carlson wondered, however, how Burnham would govern an independent Guyana. Carlson worried that the “ambitious” Burnham “has an inferiority complex with racial overtones” and that he could be “unscrupulous.”

9U.S. money, more than U.S. advice, accounted for Prime Minister Burnham’s success. The colony’s economy nearly collapsed during the period of political and racial violence from 1962 to 1964. With U.S. development assistance, British Guiana’s economy grew by 8 percent in 1965. Burnham increased the colony’s budget for capital spending by 266 percent, increasing employment in the public works sector. The new contracts to build roads and seawalls provided lucrative opportunities for Burnham and his henchmen to profit personally. Their coalition partner, Peter D’Aguiar, would grow increasingly concerned about the growth in government spending and the widespread financial corruption. Nonetheless, the new economic growth gave the appearance of peace and prosperity to outside observers. The Canadian aluminum companies increased their investments in the bauxite mining industry.

10Cheddi Jagan and his party took no part in the colony’s new political culture. The PPP adopted the motto that it had been “Cheated Not Defeated.” Until mid-1965, PPP legislators boycotted the new assembly. Jagan and the party also refused to cooperate with colonial authorities. Militant PPP members argued that the war against their party justified resorting to violence. At stormy party meetings, Jagan persuaded members to reject that option. But over the next four years, Jagan exerted little leadership. He and the party seemed content to wait for the next election, when Indians would comprise about 50 percent of the electorate.

11 In late March 1965, Jagan arrived in Cuba, staying for several weeks. The Cubans did not, however, give him a grand reception, and Cuban officials assured British diplomats stationed in Havana that Cuba had no intention of interfering in British Guiana.

12 Jagan busied himself, composing his diatribe,

The West on Trial: The Fight for Guyana’s Freedom (1966), the verbose, self-pitying, but largely accurate account of what had happened to British Guiana, the PPP, and Janet and Cheddi Jagan during the past twenty years. Accounts of Jagan’s apparent resignation reached Washington. Cheddi Jagan and his wife now appeared beaten and demoralized to Western diplomats. U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson reported that at a chance meeting with Governor Luyt at the airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico, the governor observed that he was now shocked at Jagan’s appearance. Jagan “appeared just like another scrawny little Indian.” General Consul Carlson joined in the appraisal of the Jagans, relaying a remark that Janet Jagan “looked quite old, graying, and even somewhat dumpy.” The State Department further insulted Cheddi Jagan in late 1965 when it denied him a visa to the United States to attend a “teach-in” on the war in Vietnam on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley. U.S. officials decided that Jagan, being “hopeless and beyond salvage,” could offer no “constructive criticism” to the debate on Vietnam.

13For the colonial masters, Burnham’s triumph and Jagan’s defeat posed new questions. Prime Minister Wilson’s Labour government entered 1965 assuming that the 1964 elections marked a way station and not the final destination for British Guiana. The government had pledged that independence awaited the two communities in British Guiana demonstrating that they could coexist peacefully. As indicated in conversations with U.S. officials, including President Johnson, in December 1964, Wilson thought it might take years to achieve racial harmony. The United States did not object to the United Kingdom staying, as long as it kept Jagan out of power. But the Labour government received strong criticism from its former colonies about the 1964 election and proportional representation. Canada, India, and Trinidad and Tobago all pointed out that the elections had increased racial tensions in the colony. Kwame Nkrumah, the leader of Ghana, summarized the collective dismay when he observed that proportional representation had substituted one racial party for another, and “he did not see how this could be regarded as an adequate and appropriate basis for independence.” Commonwealth countries further lamented that the United Kingdom had succumbed to U.S. pressure.

14The Wilson government attempted to address the concerns of Commonwealth members as well as those of Labour parliamentarians who continued to object to the 1964 elections in pointed questions now directed at Wilson’s own ministers. In January 1965, the Colonial Office submitted a series of papers on British Guiana that included the recommendation that a Burnham-Jagan coalition would promote racial harmony and might be the only way to prevent further bloodshed in the colony. Foreign Secretary Patrick Gordon Walker reacted angrily, telling Colonial Secretary Anthony Greenwood that “I feel strongly that we cannot consider such a coalition and must exclude it from our minds.” He reiterated the Foreign Office’s position that “cooperation with the United States on British Guiana is absolutely essential to good relations.” Prime Minister Wilson informed Greenwood that he was unhappy with both the Colonial Office and Gordon Walker and dispatched the colonial secretary to Georgetown to investigate.

15 Colonial Secretary Greenwood’s February 1965 mission to British Guiana proved a miserable failure. He informed Burnham that independence was conditioned on peace and racial justice. Burnham took the position that the glaring inequities in the civil service and security forces “was not the result of injustice but solely that of incapacity or preference” and that he would “oppose preferential treatment for members of any particular race in order to make artificial adjustments in the racial balance which emerged from sound reasons of the past.” Cheddi Jagan matched Burnham’s intransigence, refusing to consider attending a conference on British Guiana’s racial issues that included Burnham. When he returned to London, Greenwood reported on his mission to correspondents who covered Commonwealth issues and declared, “I hope never to see another small country so torn by fear and mistrust between different races.”

16Since the Waddington Commission report in 1951, the United Kingdom’s position on the future of British Guiana had oscillated wildly, as it reacted to international events and diplomatic pressures from the United States. The recommendation that Colonial Secretary Greenwood delivered to Prime Minister Wilson marked another radical shift in policy. He tacitly admitted that he had no solution for British Guiana’s problems. On 22 March 1965, the colonial secretary summarized his thinking for Wilson. The colony was doing well economically under the Burnham-D’Aguiar coalition, although Indians remained wary. Jagan remained uncooperative. The threat of violence persisted. These developments led Greenwood to reason that “on the assumption that the races will never cooperate effectively so long as we are there to hold the ring, there is much to be said for a constitutional conference later thus year leading, if all goes well, to independence in 1966.” Greenwood further proposed that the International Commission of Jurists, an international body recognized by the United Nations, should study the colony’s racial imbalances and offer solutions. Once the Burnham government accepted the report, the United Kingdom would offer independence to British Guiana.

17 In effect, Greenwood asked his prime minister to reverse the policy on British Guiana that he had enunciated a few months ago.

After some deliberation, Prime Minister Wilson accepted Greenwood’s plan. He conceded to his cabinet at a 29 March meeting that “he had personally assured President Johnson that we did not intend to grant independence until the communities in British Guiana could live together.” But the warring bureaucracies, the Colonial Office and Foreign Office, finally agreed on policy. The Foreign Office seconded Greenwood’s argument that “the demand for racial harmony gives Jagan an opportunity to stir up racial discord.” Wilson reasoned that the Johnson administration would probably not object to “an early grant of independence if this was likely to strengthen Mr. Burnham’s position, since their main concern was to keep Dr. Jagan out of power.”

18 On 1 June 1965, Wilson announced in the House of Commons that the United Kingdom would hold an independence conference in the fall. Nevertheless, Wilson apparently thought himself trapped by the course of events. In a telephone conversation with Greenwood, Wilson conveyed his “anxiety” about Burnham and raised “Dr. Jagan’s repeatedly expressed fears about a police state.” When informed that Forbes Burnham resisted receiving the International Commission of Jurists, Wilson noted on the dispatch that “we’ve been on the run ever since the constitution was fiddled. If Burnham’s the angel he is made out to be he would have agreed.”

19 Prime Minister Wilson now perhaps implicitly understood that Jagan had been prophetic in warning that the December 1964 elections would be “the end of the road.”

Beyond believing that independence under Burnham would please the United States, Prime Minister Wilson and his ministers had other reasons for abandoning a racially divided colony to its fate. Labour traditionally supported the rapid end of colonialism. When he appointed Greenwood to the cabinet, Wilson instructed the colonial secretary to work himself out of a job.

20 The Wilson government, facing severe domestic economic difficulties, also had no enthusiasm for spending money on a poor, troublesome colony. The government wanted to cut the cost of maintaining the two battalions of troops stationed there to maintain the peace. The government further persuaded itself that Burnham, in conjunction with U.S. development assistance, might bring a semblance of peace and prosperity to an independent nation. Greenwood predicted to Wilson that “East Indians would find themselves fairing a good deal better than they did under the inefficient Jagan government.” The Conservatives, led by Duncan Sandys and Nigel Fisher, seconded that view in speeches in the House of Commons.

21 Labour leaders understood that they would have Conservative support for early independence, albeit they would disappoint some of their party faithful. Finally, both Wilson and Greenwood probably took insult that Jagan no longer trusted British authorities and that he boycotted all mediation efforts. Greenwood opined that Jagan, unlike Burnham, did “not grasp how British Guiana fits into the wider scheme of things.”

22The International Commission of Jurists, under the direction of Secretary-General Sean McBride of the Republic of Ireland, visited British Guiana for two weeks in August, took testimony, and issued its report in October 1965. Consul General Carlson, at Governor Luyt’s request and with Washington’s approval, pressured Burnham to accept the commission.

23 Jagan refused to cooperate with the jurists. In its report, the commission readily documented the wide racial and ethnic disparities in the colony’s security forces and civil service. For example, Indians comprised only 300 of British Guiana’s 1,600 police officers. The jurists took a largely uncritical tone, noting that the Indian population had grown rapidly and therefore felt disproportionately underrepresented. Although they rejected quotas, the jurists recommended affirmative efforts to recruit Indians into the public services, suggesting that 75 percent of recruits into the police force over the next five years should be Indians. They further called for the appointment of an ombudsman to address allegations of racial discrimination. The jurists believed, however, that economic development and growth would resolve problems by creating more employment for all. On 20 October 1965, in a national address, Burnham accepted the report and promised that he would work for a racially integrated society in an independent Guyana.

24Shortly after pledging to work for racial equality, Burnham headed for London and the independence conference, which convened on 2 November 1965. Burnham’s acceptance of the report of the International Commission of Jurists provided the cover for the Labour government to assert that it was not abandoning the colony to racial warfare. Despite a personal plea from Colonial Secretary Greenwood, Cheddi Jagan and the PPP refused to attend the conference, calling British Guiana “virtually a police state” and comparing it to Rhodesia under the white minority rule of Ian Smith. In a letter drawn up by Greenwood and signed by Prime Minister Wilson, the British rejected the Rhodesian analogy and tartly observed to Jagan that “if your party or their supporters were concerned about the actions of the present British Guiana Government, and had genuine fears for the future, the place to express that concern and those fears was at the constitutional conference.”

25 At the conference, Burnham and D’Aguiar agreed that an independent Guyana would become a member of the Commonwealth, with the monarch as the nominal head of state. The next elections would take place in December 1968. Thereafter, Guyanese could decide whether they wanted to form a republic and leave the Commonwealth. The new constitution retained the single legislative body and the nationwide system of proportional representation. The constitution also incorporated the recommendation for an ombudsman to investigate racial discrimination. The conference fixed the date of independence for 26 May 1966. PPP members subsequently cried insult, pointing out that 26 May 1966 would be the second anniversary of the horrific attack on the Indian village of Wismar.

26 In any case, Forbes Burnham would lead the nation to independence.

As Prime Minister Wilson had predicted to his cabinet, the Johnson administration welcomed independence for British Guiana, because the process left its man in power in Georgetown. Administration officials wondered, however, whether Burnham could maintain order and hold onto power, once the British withdrew from Guyana. In August 1965, Richard Helms of the CIA warned National Security Adviser Bundy that Jagan retained the loyalty of Indians and that strikes and violence might ensue. Gordon Chase of the NSC staff offered a contrasting judgment to Bundy, noting that compared to Africans, Indians were “timid.” Without the protection of British troops, “they might be even more timid,” and “Jagan himself may decide to bug out.” Prime Minister Burnham affirmed Chase’s stereotypical, racist thinking, confidentially telling CIA agents that Indians’ loyalty to Jagan did not extend to violence. Burnham spoke with the confidence of a leader who knew that the security forces were composed of PNC stalwarts.

27 For insurance, the Johnson administration asked the Wilson government to retain British troops in Guyana after independence. The British reluctantly agreed to keep one battalion of troops there until October 1966, although they dismissed the fear that Jagan and the PPP would mount an insurrection.

28The United States concluded its years of confrontation with British authorities over British Guiana in Washington in meetings with Colonial Secretary Anthony Greenwood in mid-October 1965. Greenwood pleased Secretary Rusk, opining that Burnham had gone out of his way to be economically fair to Indians. He further predicted that the two communities would learn to live together once independence came.

29 Greenwood’s meeting with Bundy turned out more curious than his time with Rusk. An aide advised Bundy that doubts existed about Greenwood because he “is an avid reader of

The Invisible Government” (1964). In that book, David Wise and Thomas B. Ross became the first authors to provide credible evidence of CIA covert activities around the world. Bundy decided not to question the colonial secretary’s reading habits. Instead, he complimented Greenwood “on his excellent handling of a difficult problem” and twice reminded him of “the continuing Presidential interest in British Guiana—President Kennedy’s as well as President Johnson’s.”

30 Bundy need not have worried about the colonial secretary’s commitment to the Cold War. Greenwood had proved as willing, as Duncan Sandys had been, to do U.S. bidding.

In its confidential analyses, the Johnson administration took a less sanguine view of Guyana’s future than did Greenwood. Back in Washington in October 1965 for consultations, Consul Carlson told the NSC that the United States had not succeeded in establishing an alternative Indian party or finding a leader to supplant Jagan. Carlson further doubted that Burnham could woo British Guiana’s largest community to his side. He predicted that “Burnham will probably do whatever is necessary to win the election in 1968,” including establishing literacy tests to disqualify Indians. CIA analysts also took a pessimistic view of Guyana’s racial future. In late October 1965, the CIA’s Office of National Estimates reported that Jagan remained popular among Indians, although his appeal was racial and not ideological. It further noted that Indians had shown little inclination for organized violence and that “Jagan has always been more of an ideologist than insurrectionist.” Still, the CIA predicted renewed communal violence. In December 1965, the CIA’s Richard Helms informed Bundy “that the basic division of the country along racial lines would continue.” Burnham hoped that a growing economy would induce blacks from the Caribbean islands to immigrate to Guyana. He wanted U.S. help for his plan. Burnham told Helms that immigration was the “only possible course of action which would prevent Jagan returning to power with the support of the Indian community.”

31Despite concluding that Burnham and his supporters would perpetrate political crimes against the majority Indian community, the Johnson administration went forward with its policy of embracing the prime minister. The administration nominated Consul Delmar Carlson to be the first U.S. ambassador to an independent Guyana. Burnham had asked Secretary of State Rusk to make the appointment.

32 Cynical observers from the PPP might have jeered that Carlson had become a virtual member of Burnham’s cabinet. The administration also named Burnham’s friends in the U.S. labor movement to the U.S. delegation to the independence ceremonies. It asked AFL-CIO President George Meany to attend. Meany declined, asking Joseph Bierne, leader of the Communication Workers of America, to take his place. The administration also sent William Doherty Sr., the former president of the National Association of Letter Carriers. Doherty was the father of William Doherty Jr., who directed the activities of the American Institute of Free Labor Development in British Guiana.

Although union leaders represented the United States at Guyana’s independence ceremonies, they no longer shaped U.S. policy toward the South American nation. In 1964, the Jagan government had managed, after years of legal maneuvers, to force William Howard McCabe to leave British Guiana. Thereafter, the CIA man lost his cover from the American Federation of the State, County, and Municipal Employees. In 1964, Jerry Wurf replaced Arnold Zander, who had cooperated with the CIA, as president of the union. Wurf found the union bankrupt and deeply in debt. He also found “cloak and dagger types” working out of the fourth floor at union headquarters in the “International Relations Department.” Wurf fired the lot when he concluded that they had nothing to do with union business. The department head, presumably McCabe, used the pseudonym of “Harold Gray.” Wurf’s subsequent investigations revealed that his union had served as a conduit for the transfer of $878,000 in CIA funds to Latin America from 1957 to 1964. Wurf did not publicly disclose his findings. A White House acquaintance asked Wurf to meet with a CIA man at a “safe house” in Maryland. Wurf agreed to keep quiet but told the CIA that his union would no longer handle covert funds. Three years later, investigative journalists and major newspapers like the

New York Times would expose the CIA-labor connection.

33 In the aftermath of President Wurf’s inquiries, McCabe announced, on 18 September 1964, to his “brothers” in the union movement the closing of his department for “financial and structural reasons.”

34Gene Meakins, ostensibly of the American Newspaper Guild, directed the CIA-union effort in British Guiana through 1964. Since 1963, the Jagan government had tried to deport Meakins, but with the assistance of the U.S. consulate, Meakins had fought the deportation order in the colony’s courts. Meakins left British Guiana on 9 December 1964, two days after the 1964 elections. Meakins had worried through 1964 that he would be killed by a bomb, writing to Andrew McLellan of the AFL-CIO that “people have told me I am high on the PPP’s list.”

35 After Meakins’s departure, the only visible union activity in Guyana was the American Institute of Free Labor Development’s project, first announced in 1962, to build low-cost housing for Guyanese unionists. Director William Doherty Jr. thought that with Jagan out of the way, the American Institute could proceed with its plans. By 1969, Doherty had to report to the American Institute’s directors that the $2 million loan had been lost and that the 568 housing units had not been built. Guyanese union officials, who were associated with Burnham and the PNC, had stolen the money through exorbitant salaries and personal loans.

36On 26 May 1966, in an impressive ritual, the United Kingdom transferred power to Forbes Burnham and the new nation of Guyana. The independence ceremony had been preceded by a visit to the colony by Queen Elizabeth II. Colonial Secretary Greenwood led the United Kingdom’s delegation. Duncan Sandys, the official who had mandated the proportional representation scheme, was Burnham’s guest of honor at the ceremonies. The PPP boycotted both the queen’s visit and the independence celebrations, although Jagan attended the flag-raising ceremony. Continuing his policy of trying to project an inclusive attitude, Burnham embraced Jagan at the flag-raising ceremony.

37In his last dispatch from Georgetown, Governor Richard Luyt pronounced the United Kingdom’s 153 years of colonial rule a success. Guyana, he concluded, “goes forward with a fair chance of a peaceful and prosperous future.” He called Burnham “statesmanlike” for accepting the report by the International Commission of Jurists and suggested that Burnham would rectify the racial imbalances in the security forces. He further thought that racial tensions would diminish in an independent state. His reading of Guyana’s evolving demography led him to estimate that the PPP would win 49.4 percent of the vote in the next election, if racial bloc voting persisted. Indians might, however, choose other parties if Burnham could deliver peace and some prosperity. Luyt placed his bet on Burnham holding his coalition together and winning the next election. The governor attributed this rosy scenario to the decision to conduct the 1964 election under the system of proportional representation.

38 Luyt left Georgetown with an obvious sense of satisfaction that he had been the official who had overseen the implementation of proportional representation. Subsequent developments in Guyana’s political culture would demonstrate that Governor Luyt had deluded himself about his contribution to the colony’s future.

PRIME MINISTER BURNHAM did not seize the opportunity to foster a healthy and harmonious political culture in the new Guyana. Burnham was not merely in office, as Cheddi Jagan had been under British colonial rule. Burnham exercised real power. He took control of a richly diverse society. According to tabulations done in December 1964, 641,500 people, a 12 percent increase in population in the 1960s, resided in Guyana. The survey showed that Indians with 320,000 and blacks with 200,000 made up the two largest communities in the nation. People classified as mixed race constituted 79,000 of the population followed by Amerindians with 29,500. Portuguese, Chinese, and other Europeans accounted for another 13,000 people.

39 For the first time in the country’s history, Indians constituted an absolute majority of the population, but they were excluded from exercising power in the parliamentary system dominated by Burnham and the People’s National Congress and Peter D’Aguiar and the United Front. Burnham had pledged to treat all communities fairly and to implement the recommendations on racial justice of the International Commission of Jurists. But as Jagan had appropriately asked Colonial Secretary Greenwood in 1965, “Who will compel the coalition government to carry out its promises if it fails to do so?”

40 In fact, Burnham ignored the report on racial justice. The police and security forces did not reflect a broad cross section of Guyanese society. At the end of the 1960s, blacks still made up 75 percent of the personnel in police and military. Officers in these security forces were closely tied to Burnham and the PNC. Shortly after independence, Burnham’s government passed a National Security Act, which empowered the government to suspend the writ of habeas corpus and detain Guyanese on national security grounds. Burnham constantly looked for an excuse to arrest Cheddi Jagan and his key followers and to proscribe the People’s Progressive Party. U.S. intelligence analysts confirmed this when they reported in late 1967 that Jagan “knows that Burnham needs scant excuse to jail him, or to outlaw his party, and that the Negroes are generally more adept than his own East Indian followers in the tactics of violence.”

41Beyond intensifying racial discrimination in Guyana, Burnham began to bankrupt the nation through mismanagement and financial corruption. As during the colonial period, the nation’s economy depended on the sale of sugar, bauxite, and rice. Booker Brothers produced the sugar on fifteen large plantations, and the Canadian aluminum companies mined the bauxite. On small plots of land, Indian farmers produced the country’s surplus rice. The United Kingdom remained Guyana’s major trading partner. Prices for these primary products fluctuated wildly. The prices also declined relative to the cost of imported manufactured goods. Nonetheless, Guyana managed to achieve a small surplus of trade in the 1960s. The nation supplemented that income with significant amounts of foreign aid from 1965 through 1969. Burnham’s budget for 1969, for example, counted on $46 million in grants and loans from the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United Nations, with the United States providing about 60 percent of the aid. Despite the aid and small trade surplus, Guyana enjoyed only a minuscule rate of economic growth in the second half of the 1960s. At the end of the decade, per capita income was still below that of 1961, the last peaceful year in the colony’s history. Unemployment remained stubbornly high at 20 percent. Poor prices for exports combined with rapid population growth burdened Guyana’s economy.

42 But Burnham and his henchman also stole from the nation. In 1967, Peter D’Aguiar discovered that approximately $580,000 had been illegally spent on a highway and that the director of audits could not account for another $11.7 million in government spending. D’Aguiar became further incensed as Burnham padded the job rolls in the civil service, judiciary, and police with PNC faithful. In September 1967, D’Aguiar quit Burnham’s cabinet in disgust.

43Jagan and the PPP observed but did not participate meaningfully in Guyana’s political life from 1966 through 1968. After independence, Jagan took his seat in the legislature. In his inaugural speech, Jagan charged that the method of independence had been unfair and would perpetuate divisions in Guyanese society. Jagan predicted that the PPP would win a free and fair election. Jagan understood, of course, that Guyana’s demographic evolution favored the PPP. Jagan also repeatedly protested that he did not expect a fair election in 1968. Outside observers agreed that Indians remained devoted to Jagan. The CIA noted that Indians “idolized” Jagan. Ambassador Carlson apparently thought that the CIA exaggerated, for he characterized Jagan “as only a demigod to Indians.” Carlson further observed that Jagan had become increasingly bitter about Guyana’s political life and more of a doctrinaire leftist. In November 1967, Jagan attended in Moscow the fiftieth anniversary celebrations of the Bolshevik Revolution. Despite Jagan’s purported leftward drift, no one anticipated revolutionary upheaval in Guyana. The CIA thought violence unlikely, “given the docile nature of the East Indians, plus their fear of the Negroes.”

44 The new British representative in Guyana, High Commissioner T. L. Crosthwait concurred, noting Indians held “a common fear of Negro domination.”

45 Such comments underscored the limited freedom Jagan and the PPP had in independent Guyana. With his control of security forces, Burnham had created a repressive dictatorship, with the trappings of a parliamentary democracy.

The United Kingdom watched Guyana’s descent into tyranny. British diplomats focused on bilateral trade and investment issues, recognizing from June 1966 on that effective influence on Guyana and Burnham would have to come from the United States. High Commissioner Crosthwait and career officials in the Commonwealth and Colonial Office took a pessimistic view of Guyana’s future. They rejected the rosy scenario that Governor Luyt had created in his last dispatch. They believed that Guyana’s vicious racial divisions would persist. They also discounted Luyt’s prediction that some Indians would forsake Jagan and the PPP. Furthermore, Burnham could be counted on to withdraw from his alliance with D’Aguiar. British officials assumed that Burnham would either rig the next election or find a pretext for crushing his political rivals. If Jagan was permitted to win an election and gain power, they expected that the United States would intervene in Guyana. In fact, in July 1966, Walt Rostow, President Johnson’s new national security adviser, brusquely informed an aide to Prime Minister Wilson that the United States “would be very concerned” if Jagan returned to power and that the British should disabuse themselves of any other conclusion. As Sir John B. Johnston in the Commonwealth Office summarized the British dilemma, “It is not a pleasant prospect to contemplate our continuing to support an authoritarian regime which has departed from a democratic constitution because the alternatives would be worse.” Johnston conceded, however, that his government had already adopted such a policy in regard to Pakistan, Uganda, and Nigeria.

46 In Guyana, also, the Wilson government backed an authoritarian. With U.S. encouragement, British military officers provided training and assistance to the Guyana Defense Force, reasoning that a trained and equipped army would prevent disorders in Guyana.

47 An effective Guyana Defense Force would also presumably bolster the Burnham regime.

Unlike the Wilson government, the Johnson administration spent little time questioning Burnham’s rule in Guyana. Only intelligence analysts based in Washington told the truth about Burnham, repeatedly warning that Burnham was determined to hold on to power and would find the best “legal” way to perpetuate his rule. The CIA and State Department’s Office of Intelligence and Research based their judgments on solid evidence. The CIA had sources in the upper echelons of the PNC who reported on the machinations of Burnham and his henchmen.

48 Ambassador Carlson dominated the debate, however, about Burnham. He dispatched positive reports about Guyana and explained away Burnham’s crimes. At Burnham’s request, the ambassador also ordered his embassy staff to have no contact with Cheddi Jagan. According to Carlson, Guyana had followed a “remarkable” pro-West line, and its economy thrived under Burnham’s direction. In 1967, Burnham toyed with the idea of establishing diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. Carlson reminded Burnham that “he had given me his word that when he came to power he would not recognize the Soviet Union.” Carlson happily reported that Burnham dropped the idea. Carlson also kept Washington apprised of Guyana’s voter rolls. In mid-1967, he estimated that the Burnham-D’Aguiar coalition would win 5,436 votes more than the PPP. By the end of 1967, he feared that the PPP could win 50.1 percent of the vote.

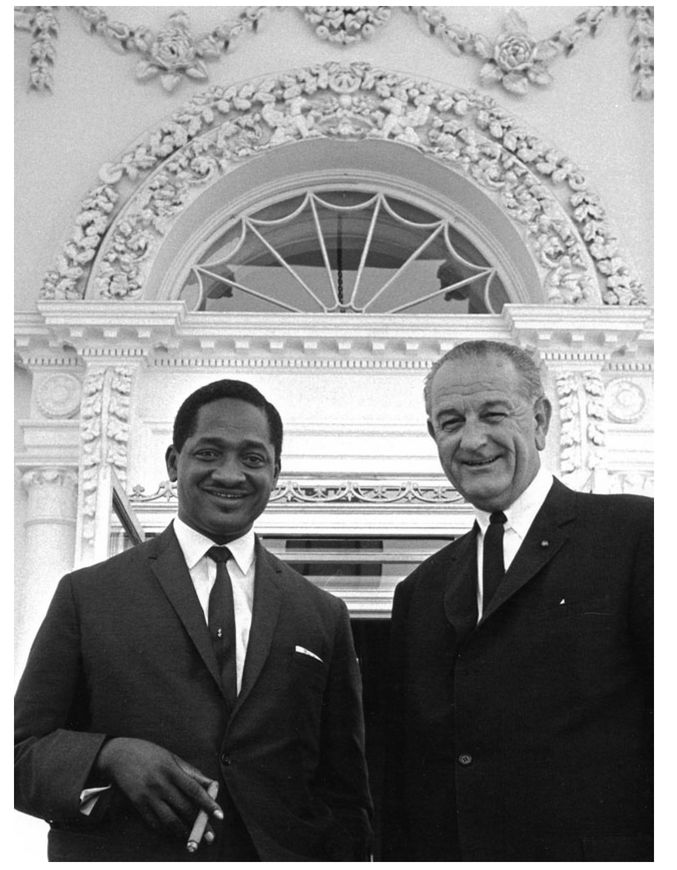

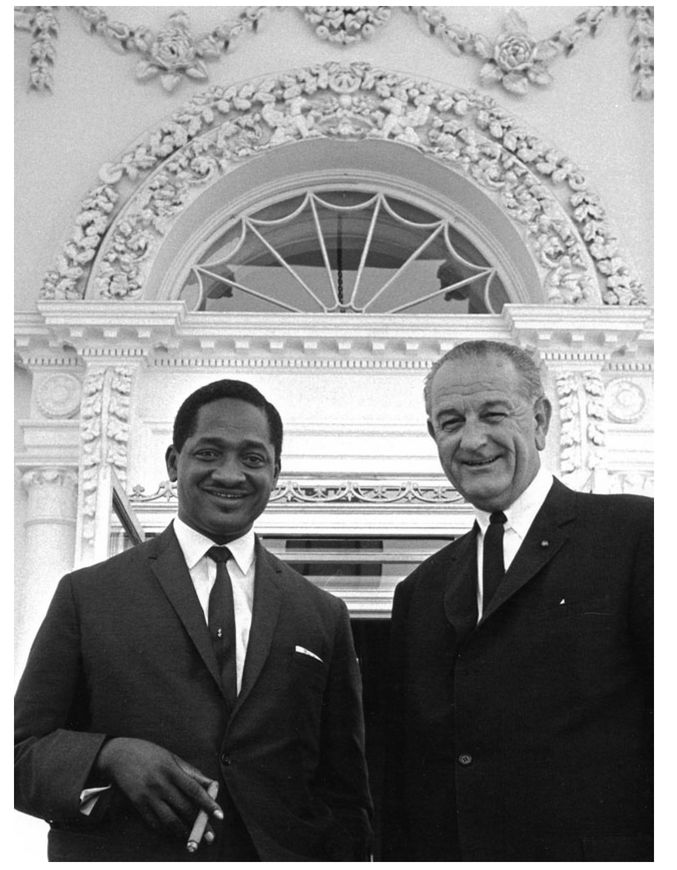

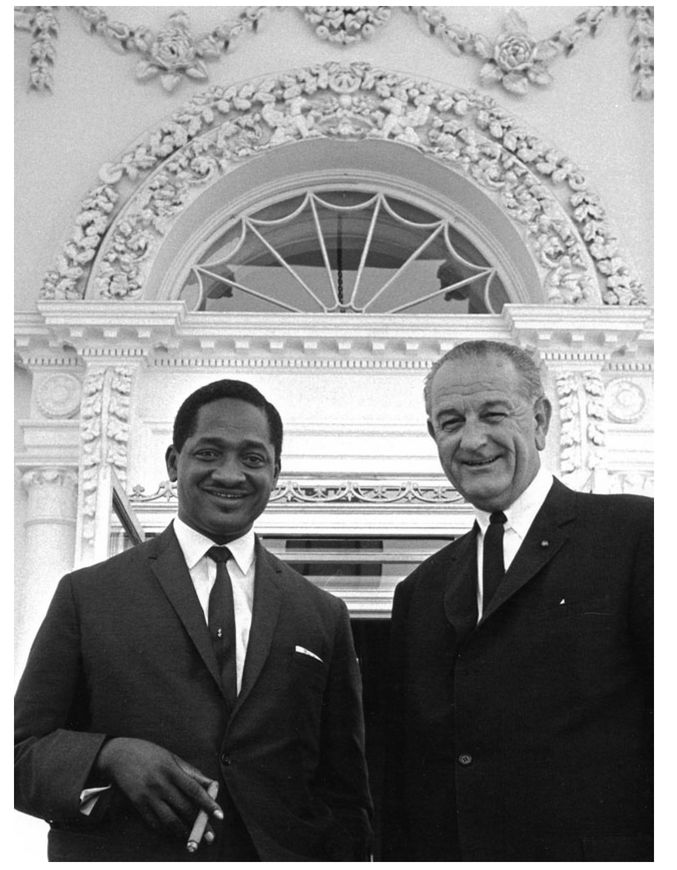

49The Johnson administration found no fault with Ambassador Carlson’s positive assessments of Burnham. In July 1966, President Johnson met Prime Minister Burnham in Washington, greeting him on the south lawn of the White House and hosting a luncheon for him. Thereafter, the White House arranged for Burnham to take a trip across the United States on Air Force Two. National Security Adviser Rostow briefed his president, telling Johnson that Burnham had done a “highly commendable” job in alleviating racial tension and promoting economic growth. Rostow added: “What most concerns him—and us—is to increase his political base sufficiently to win a clear majority over Jagan in the 1968 election.” Burnham emerged from the White House in a jubilant mood. Burnham told Carlson that he supported Johnson’s policies on civil rights and the war in Vietnam, and Johnson, in turn, approved of his plan to attract black emigrants to Guyana. According to Burnham, Johnson declared, “Remember you have one friend in this corner going for you and his name is Lyndon Johnson.”

50 The bountiful economic aid package for Guyana that Johnson approved, dubbed a “golden hand-shake” by State Department officers, gave substance to those words. The administration also dispatched agents from the Public Safety Program of the Agency for International Development to train Guyanese police. No U.S. official questioned Burnham as to why he had reneged on his pledge to fulfill the report of the International Commission of Jurists and desegregate the police force, although CIA analysts documented the continued discrimination. Burnham undoubtedly impressed U.S. officials with his commitment to racial justice when he gave in April 1968 a fine speech, “To a Martyr,” in tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Burnham also led a candlelight procession through Georgetown in memory of the slain civil rights leader.

51Although the United States supplanted the United Kingdom as the dominant power in Guyana, U.S. citizens did not become leading players on the Guyanese stage. U.S. investors and traders continued to have negligible interest in the independent nation. Ambassador Carlson reported that only 600 U.S. citizens lived in Guyana in mid-1967. Shrimp fishing constituted their most important commercial enterprise. U.S. missionaries, about 150 Christians, constituted the largest group of U.S. citizens in Guyana.

52 Many propagated their faith in interior villages populated by Amerindians. Carlson also noted that representatives of the Christian Anti-Communist Crusade had returned to Guyana. Jagan had expelled the organization in the early 1960s for interfering in the colony’s domestic political affairs. As it had since 1953, the U.S. officials thought of Guyana almost solely within the context of the Cold War. The Johnson administration accepted the finding of the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations that an independent Guyana led by Cheddi Jagan would enhance the power of the Soviet Union and diminish the security of the United States.

The absolute determination of the United States to keep Jagan from returning to power can be assessed in a conspiracy discussed at the end of 1966 in the State Department’s Division of American Republic Affairs. After Guyana gained independence, the State Department moved responsibility for Guyana from the Division of European Affairs and the Bureau of North American Affairs over to its Latin American section. In a memorandum to his boss, Robert Sayre, the director of American Republic Affairs, Harry Fitzgibbons noted that the United States wanted Jagan to be exiled from Guyana and that it might be able to achieve that objective by encouraging Jagan “in the kind of activities which would support (politically if not legally) a move to exile him.” Fitzgibbons assumed that Jagan would “involve himself in subversive activities including terrorism,” if he learned that Burnham, with U.S. and United Kingdom support, planned to rig the next election. Fitzgibbons proposed various ways to “leak” disinformation to Jagan. He suspected “that Cheddi will decide that he can’t afford the luxury of insulating himself from the planning and preparation, if not the execution, of the PPP’s counterattack.”

53 Whether the Johnson administration played the part of an

agent provocateur cannot be established by available evidence. When Jagan actually learned that Burnham would violate basic democratic procedures, he walked out of the Guyanese legislature, but he did not encourage or engage in violence. The United States did, however, aid and abet Burnham in his plot to conduct a fraudulent election.

Prime Minister Forbes Burnham and President Lyndon Johnson outside the White House, 21 July 1966. Photograph by Yoichi Okamoto, LBJ Library.

By mid-1968, Burnham had a comprehensive plan to steal the election. His scheme to encourage blacks from the Caribbean islands to immigrate to Guyana had not worked out. Guyana’s high unemployment rate discouraged everyone. Instead, Burnham told party leaders that he planned to limit the registration of Indians and register underage supporters of the PNC. In addition, he would increase the use of proxy voting, arrange for Guyanese overseas to vote, and provide false voter registration cards for Guyanese living in the United Kingdom, Canada, and Caribbean islands. Burnham no longer wanted to deal with his coalition partners, Peter D’Aguiar and members of the UF. The CIA reported that, at the closed party meeting in early June, “Burnham said that he will rig the election in such a way that the PNC will win a clear majority.”

54 Burnham had already publicly signaled his intentions, surprising party members in April 1968 at the annual PNC congress with the promise that he would seek an absolute majority in the next election. Burnham’s manipulation of voter registration rolls became apparent as the December 1968 election approached. The domestic register of voters showed nearly a 24 percent increase from the 1964 register. In one PNC stronghold, the number of registered voters increased by over 100 percent. The manipulation of the domestic voter rolls paled compared to the scams Burnham and his acolytes carried out abroad. The overseas register listed 70,541 eligible voters, with 45,000 of them living in Great Britain. British census figures demonstrated that approximately 20,000 Guyanese lived in Britain in 1968. Such fraud prompted D’Aguiar to join Jagan in late October 1968 in walking out of Guyana’s legislature. D’Aguiar subsequently went to Great Britain to investigate the overseas voting rolls.

55British journalists, both in the print and electronic media, exposed Burnham’s deceptions and confirmed D’Aguiar’s suspicions. Guyana had become a subject of public debate, for in 1967 in two comprehensive articles, the

Sunday Times of London had revealed how the Kennedy administration and the CIA had, with the acquiescence of Prime Minister Macmillan and Colonial Secretary Sandys, destabilized the Jagan government.

56 On 9 December 1968, the Granada Television Company produced a thirty-minute documentary,

The Trail of the Vanishing Voters. The documentary opened showing two horses grazing at 163 Radnor Street in Manchester, where “Lilly and Olga Barton” were registered to vote in Guyana. Using the resources of the Opinion Research Centre, a respected polling organization, the television producers demonstrated that only 150 voters had valid registrations out of a sample of 1,000 voters. Many of the addresses listed on the rolls did not exist. Granada’s journalists checked 550 names in London and found only 100 valid voters. After Guyana’s election, Granada’s journalists tried to analyze the domestic voter rolls, but Burnham barred their entry into the country. The journalists decided instead to examine the voter lists in New York City and again found that most of the people and addresses did not exist. A second documentary,

The Making of a Prime Minister, appeared in early January 1969, just as Burnham arrived in London for a Commonwealth meeting. The documentary presented authorities testifying that Burnham’s fraud was unprecedented in the history of Commonwealth nations.

57The Johnson administration did more than explain away Burnham’s destruction of Guyanese democracy; it knowingly helped the prime minister commit his political crimes. On 21 November 1967, Thomas Hughes, the director of the State Department’s Division of Intelligence and Research, presented the “dilemma” for the United States to Secretary of State Rusk. Analyzing the voter roles, Hughes could not guarantee that Jagan and the PPP would not win the 1968 election. He further observed that “the Negroes presently have no intention of surrendering power, and they might not surrender it even if Jagan wins the election.” But if Burnham did lose, Hughes wondered whether the United States “could support Burnham’s illegal self-perpetuation in power with consequent damage to the growth of democratic processes in Guyana.”

58 Rusk indirectly addressed Hughes’s observation by aiding Burnham. The State Department asked its embassies around the world about absentee voting laws. Burnham employed a U.S. firm, Shoup Registration Systems, Inc., to enroll voters. Scholars have asserted that the company had ties to the CIA. Paul Kattenberg, who served as the deputy chief of mission in the U.S. embassy in Georgetown, confirmed those assertions in an oral history interview in 1990, when he related that the Johnson administration authorized a “very costly and considerable” clandestine operation to assist the PNC in the 1968 elections. Kattenberg characterized the operation as “absolute baloney” and informed Ambassador Carlson that he would not take part in it. Unlike Carlson, Kattenberg judged Cheddi Jagan to be “a fairly reasonable politician.”

59 In January 1968, Rusk arranged for Burnham to visit again with President Johnson. Burnham was in Washington to have his throat examined at the Bethesda Naval Hospital. Rusk reminded the president that Burnham “was well aware that we support him because he is virtually the only Guyanese who has the popularity and political acumen to lead a democratic government in Guyana and keep Communist-oriented Cheddi Jagan from power.” Johnson again had a pleasant discussion with Burnham, although at Walt Rostow’s urging, Johnson advised Burnham to keep his coalition with D’Aguiar together.

60As the extent of Burnham’s manipulation of the voter registration lists became known, the State Department suggested moderation to Burnham. John Calvert Hill, who had served as the department’s liaison with the CIA, asked Ambassador Carlson to speak with Burnham. On 29 June 1968, Carlson told Burnham that friends of Guyana in Washington feared that he would use “Tammany Hall tactics” and “embarrass” the United States. Burnham wanted to know what was “reasonable.” Carlson artfully replied that “the matter was not one of any precise equation but simply one of dimension.” The ambassador added, “We wanted him to win, we had backed him to the hilt; neither of us wanted a scandal.” The amenable Burnham accepted Carlson’s point and noted that he would register 50,000 new voters overseas, with 30,000 of them voting. Burnham expected to win 75-90 percent of the overseas voters. His new law allowed the descendants of Guyanese mothers and the wives of Guyanese to vote. Carlson concluded from this colloquy that Burnham’s “intentions were much more reasonable than had been feared” and that Burnham “is not planning or expecting a massive rig.” Writing for Rusk, Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs Covey Oliver congratulated Carlson on his performance and seconded his decision not to press Burnham further on electoral issues.

61As the 16 December 1968 election approached, the CIA and the State Department’s Division of Intelligence and Research kept administration officials fully informed of Burnham’s electoral machinations. Embassy officials in London also provided details on the Granada Television documentary. Thomas Hughes calculated that, in a fair election, the PNC would win only 39 percent of the vote. Burnham had taken personal control of the ballot machinery, while simultaneously maintaining a “dignified, statesman-like posture.” Hughes also reported that neither Cuba nor the Soviet Union aided the PPP.

62 Reports of electoral fraud did not disturb President Johnson and his aides. In July, President Johnson approved a $1 million PL 480, “Food for Peace,” loan and an additional $2.5 million of supporting assistance. As National Security Adviser Rostow explained to the president, “the overriding consideration is to give Mr. Burnham additional resources with which to carry on development projects with high political impact.” On 23 November 1968, three weeks before Guyana’s election, Johnson approved a $12.9 million loan to modernize the rice industry. William Gaud of the Agency for International Development recommended the loan to Johnson, noting that the loan made economic sense and would ameliorate racial tensions by persuading Indian rice farmers to vote for the PNC. He opined that Burnham directed a “moderate, efficient government” and that the PPP had run a “radical, inefficient, racial” government. Gaud wanted the loan approved immediately so as to influence the election but not to appear to be doing so. Rostow agreed with Gaud, telling Johnson that “the rice loan project plays a key part in Burnham’s electoral strategy” and would help to guarantee his election. Rostow arranged for Ambassador Carlson to announce the loan in Georgetown during the last week of November 1968.

63Prime Minister Burnham and the PNC claimed a massive victory in mid-December 1968. Electoral officers announced that the PNC had won 55.8 percent of the vote and deserved thirty of the fifty-three seats in the legislature. The PPP garnered only nineteen seats and the UF won four seats. The PNC built its victory by allegedly winning most of the 19,297 proxy votes and 94.3 percent of the 36,745 overseas votes. Electoral officials did not explain whether Lilly and Olga Barton, the grazing horses of Manchester, also favored the PNC. Beyond creating votes, Burnham’s henchman, led by Minister of Home Affairs Llewellyn John, took other measures to rig the election. Guyanese had traditionally counted ballots in electoral districts. Minister John ordered ballot tabulations to be conducted on three locations, providing opportunities for PNC operatives to tamper with ballot boxes while in transit. PNC thugs also intimidated Indian voters.

64Despite overwhelming evidence of electoral fraud, Ambassador Carlson did not judge the election “a massive rig.” After analyzing the vote, he told Washington that allegations of fraud were an “exaggeration.” Carlson’s superiors agreed with his judgment. The State Department recommended that President Johnson congratulate Burnham, noting the election “went off remarkably smoothly.” It further claimed that “Burnham’s largely Negro party for the first time made substantial inroads into the East Indian community which Jagan leads.” The United States had finally achieved its long sought objective in Guyana. Summarizing U.S. policy for Johnson, the department cheered that “Burnham’s election victory caps four years of intensive effort to concentrate his government democratically against the Jagan threat.” U.S. support “has been extremely important to Burnham throughout this period.” President Johnson, who was soon to step down from office, accepted the recommendation, sending a personal note of congratulations to his friend, Forbes Burnham.

65Peter D’Aguiar, the erstwhile anticommunist ally of the United States, did not delude himself that democracy and racial justice had triumphed in his homeland. Both in an interview with John Calvert Hill of the State Department and on the Granada Television documentary,

The Making of a Prime Minister, D’Aguiar confessed his sins and bewailed the fate of Guyana. In January 1969, he told Hill that the recent elections were “fraudulent without finesse.” Hill agreed but responded that it would be “inappropriate” for the United States to take a stand on the issue. D’Aguiar further observed that Jock Campbell, the chairman of Booker Brothers, accepted his assessment that Burnham would now establish a dictatorship. D’Aguiar cried that “U.S. support had enabled Burnham to establish a firm position from which he could probably not be dissuaded from following extreme policies against other races.” D’Aguiar blamed himself for cooperating with Burnham, although he did not apologize for his complicity in the violence of 1962. On television, D’Aguiar reiterated his opposition to communism but lamented that Burnham’s crimes would create a pretext for violent revolution. Disgusted and humiliated, the wealthy D’Aguiar retired from Guyanese politics.

66 His prophesy about dictatorship and racial tyranny in Forbes Burnham’s Guyana came to pass.

FORBES BURNHAM AND HIS People’s National Congress practiced the politics of squalor in Guyana. Burnham, who created a personality cult, dominated the nation until he died from a heart attack in August 1985. The PNC, under Burnham’s henchman, Desmond Hoyte, carried on until 1992. Burnham and his followers perpetrated despicable crimes against the Guyanese. They rigged elections, murdered political opponents, persecuted Indians, stole money, ruined the economy, and impoverished the nation. They created a society of crime, misery, fear, and hunger. International observers began to compare the squalid nature of life in Guyana to that in Haiti under the crazed dictator François “Papa Doc” Duvalier (1957-71) and his venal son Jean-Claude Duvalier (1971-86).

The PNC motto was that “it is either we or the coolies who will run Guyana.” The party transformed the denial of political power to the majority Indian population into an art form dubbed “fairytale elections.”

67 The government conducted national elections and referendums in 1973, 1978, 1980, and 1985. Each announced electoral result seemed more ludicrous than the previous one. In 1973, electoral officials claimed that the PNC share of the vote had risen from 55.8 percent in 1968 to 70.1 percent. By 1985, the PNC claimed over 80 percent of the vote and forty-two of the fifty-three seats in the legislature. The party used the electoral tricks of 1968—overseas voting, proxy voting, centralized counting—to compile its majorities. Instead of relying on government officials to carry out the fraud, Burnham and the party assigned the army to oversee elections. Military men provided the additional luxury of being able to intimidate Indian voters. In 1980, opposition parties invited an international team of human rights advocates to observe the elections. In their report, the observer team noted that a local calypso artist sang the lyric that “the elections in Guyana will be something to remember.” The team concluded that the singer had made an ironic point, for Guyana’s elections served “as an example of the way an individual’s determination to cling to power at all costs can poison the springs of democracy.”

68 That report confirmed what Burnham had once said to the United Kingdom’s representative in Georgetown. Guyana’s prime minister responded to allegations of electoral fraud by noting that “I read the Holy Bible regularly and I can assure you that there is nothing in it about one man, one vote.”

69Beyond scriptural teachings, Burnham relied on security forces and the civil service to preserve his dictatorship. After 1964, Burnham rapidly expanded the size of security forces in Guyana. In 1964, British Guiana had approximately 2,000 police and soldiers. By 1980, the number of armed personnel exceeded 20,000, with 4,500 in the police force and 7,500 in the Guyana Defense Force. Another 8,000 belonged to paramilitary groups like the Guyana National Service and the People’s Militia, which were closely tied to the PNC. The security forces were essentially segregated units, with Afro-Guyanese comprising over 90 percent of the personnel. Burnham continued to violate the pledges he had made to the International Commission of Jurists to seek a racial balance in the civil service and security forces. The paramilitary units proved especially vicious, inflicting a reign of terror on Indians. Known in Guyana as “kick-down-the-door gangs,” these armed units employed commando tactics in invading Indian homes. The gangs robbed family members, assaulted the males, and raped women and young girls. Indian housewives in rural areas took to congregating by the public roads during the day, because they feared being attacked in their isolated homes. The robberies served as a form of PNC patronage. Young thugs were permitted to rob and terrorize Indian families in return for their loyalty to the regime. Such lawlessness characterized life in Burnham’s Guyana. By the 1980s, Guyana had the second highest crime rate in the world, exceeded only by the crime rate in war-torn Lebanon. Common criminals favored the technique known locally as “choke and rob.”

70Cheddi Jagan and the PPP characterized the racial tyranny of Guyana as a “Rhodesia in Reverse,” referring to that state’s white minority government. A more apt African comparison was Uganda, where the grotesque dictator Idi Amin drove 80,000 Asians, mostly Indians and Pakistanis, out of the country in 1972. Burnham never ordered Indians to leave Guyana but he made their life intolerable. After the electoral fraud of 1973, 5,000 to 7,000 people a year left Guyana. In 1978, 13,000 people fled the country, which was an extraordinary number of emigrants for a country of 700,000 people. Emigrants included educated Indians and blacks, and they headed for Canada, Great Britain, and the United States. In 1990-91, the census takers in Canada and the United States counted 181,000 Guyanese living in North America. Others estimated that 400,000 Guyanese lived abroad by 1991.

71 Burnham did not, however, direct his political repression solely at Indians. In the mid-1970s, a new political organization, the Working People’s Alliance (WPA), began to challenge the PNC, calling for a boycott of the 1978 referendum. The WPA, initially founded by blacks, began to appeal to Indians and declared itself a political party in 1979. On 13 June 1980, an individual associated with the Guyana Defense Force gave Walter Rodney, the leader of the WPA and a prominent historian, a bomb disguised as a walkie-talkie. After Rodney’s assassination, the Burnham regime continued to repress WPA activists, arresting Dr. Rupert Roopnarine, for example, nineteen times between 1979 and 1986.

72 The American Historical Association posthumously awarded Walter Rodney the prestigious Beveridge Prize for his study,

A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905 (1981).

Burnham had other inducements for PNC faithful not inclined toward violence. He padded the civil service rolls with his supporters. At times, the payroll for the civil service consumed 50 percent of the government’s budget. Burnham created enormous new opportunities for lucrative employment, graft, and corruption in the 1970s. After eliminating the capitalist-oriented United Front party from the government in 1968, Burnham began to pursue what he labeled “cooperative socialism.” Neither international nor domestic analysts could define Burnham’s new theory of political economy. In practice, it meant nationalizing the economy. Burnham expropriated the foreign enterprises, the Canadian and U.S. bauxite mining companies and the sugar estates of Booker Brothers of the United Kingdom. He also nationalized foreign and domestic banks, the pharmaceutical distribution system, and private schools. By the end of the 1970s, the government controlled 80 percent of the economy. A prerequisite for employment in the new government enterprises was a PNC membership card.

73 As U.S. Ambassador John R. Burke, who served in Georgetown from 1977 to 1979, recalled, Burnham mandated that the government control the economy, because he feared that the Indian majority of Guyana would flourish in a free, open, competitive economy.

74Burnham and his criminal gang repeatedly demonstrated that they knew how to manage an election. Their skill at electoral fraud did not, however, translate into business acumen. In the 1970s and 1980s, Burnham and the PNC turned Guyana into an economic facsimile of Haiti, the region’s poorest nation. After the nationalization of foreign enterprises, the country became starved for outside capital, technology, and managerial talent. In fact, Guyana transferred significant financial resources abroad as it compensated the British, Canadian, and U.S. companies. Burnham also spurned foreign aid for a time, arguing that international lending agencies acted selfishly and that foreign aid was incompatible with his vision of cooperative socialism. The major export industries—sugar, bauxite, rice—predictably collapsed, with significant declines in output and exports. In the 1960s, Guyana had managed small balance of trade surpluses. In the 1970s and 1980s, Guyana almost always bought significantly more than it sold. As the economy disintegrated, Guyana began to borrow heavily from private banks and international agencies. By the 1980s, the servicing of the debt consumed over 30 percent of the government’s budget, leaving little money for investment in human and physical infrastructure. To be sure, poor global prices for bauxite, sugar, and rice and the rapid rise in oil prices after the Arab oil embargo (1973) and the Iranian Revolution (1979) compounded Guyana’s problems. But gross economic mismanagement combined with the wholesale corruption of Burnham and his cronies caused the country’s financial debacle.

75The collapse of Guyana’s economy reduced the population to absolute misery. Georgetown experienced periodic breakdowns of electricity and water supply. Sewage systems deteriorated, leading to a rapid increase in gastrointestinal diseases. The government failed to maintain seawalls, canals, and dikes. When floods inevitably followed, Hamilton Green, the minister of public works, blamed PPP saboteurs for the disasters. Inflation raged out of control; prices rose over 450 percent between 1970 and 1983. The unemployment rate shot up to 30 percent. The minimum daily wage amounted to less than $1.00. Doctors and other medical personnel fled the country; government-owned hospitals became breeding grounds for disease. Short on foreign currency, the Burnham government banned the import of essential foodstuffs like wheat even as the domestic output of rice declined. It actually became a crime in Guyana to be in possession of a loaf of bread. PNC minions distributed scarce food at party-controlled outlets. Malnutrition increased, with one mid-1980s study showing that 71 percent of children under five years old had confirmed symptoms of malnutrition.

76As Guyanese starved, Prime Minister Forbes Burnham celebrated his personality. He preferred being addressed as “Comrade Leader.” Although he had no military training, Burnham appeared in public in military uniform, bearing the insignia of a general. According to British diplomats, one story that circulated at Georgetown Christmas parties related that “our Great Leader has decided that he no longer wishes to be known as the P.M. As everything begins with him, he wants in the future to be known as the A.M.”

77 Burnham had indeed assumed the role of King Louis XIV of France. He had become the state of Guyana. As the economy and social services crumpled around him, Burnham commanded a costly national celebration of his sixtieth birthday in 1983. Burnham’s delusions of grandeur persisted even after his death. His sycophants, apparently carrying out Burnham’s last command, displayed his embalmed body in a glass casket. But in the Guyanese heat, the body deteriorated and had to be buried.

Burnham’s Guyana became a haven for bizarre, weird movements. One religious cult, the House of Israel, served as a private army for the PNC. The House of Israel, which claimed a membership of 8,000, had no relationship to the state of Israel or to Judaism. It was a black-supremacist group that held that blacks were the original Hebrews and that Jews living in Israel were imposters. David Hill, an African American who had fled criminal charges of blackmail, larceny, and tax invasion in the United States, headed the cult. Other fugitives from U.S. justice joined the group. House of Israel brutes broke up anti-PNC strikes and demonstrations and, in one case, murdered a Roman Catholic priest. U.S. citizens also formed Guyana’s most notorious cult, the People’s Temple of Christ led by the Reverend Jim Jones. Jones and over 900 disciples committed mass suicide on 18 November 1978 at the “Jonestown” compound. Before the mass suicide, the People’s Temple had been intimately involved with the PNC. It lobbied on behalf of the PNC, and Jones’s disciples probably voted in the 1978 referendum. Temple leaders also arranged sexual affairs for PNC officials with female members of the cult. In truth, the People’s Temple also developed ties with respectable sectors of the Guyanese community, such as the Guyanese Council of Churches.

78Burnham’s international policies proved as disastrous for his country as his domestic initiatives. International observers remarked that the ambitious Burnham yearned for a leading role on the international stage and that he craved international recognition. He also apparently felt embarrassed that he was widely perceived as the product of CIA machinations.

79 Burnham’s debut occurred in September 1970, when he attended the Lusaka Conference of Non-Aligned Nations. Guyana was the only Western Hemisphere nation to participate fully in the conference. At the conference, Burnham pledged that Guyana would make a $50,000 annual contribution to back those working to overthrow white minority rule in southern Africa. While in Africa, Burnham and his entourage happily observed the development of one-party rule in African states like Ethiopia and Uganda. In 1972, Burnham hosted a lavish meeting of foreign ministers of the nonaligned movement in Georgetown. Delegations from seventy-nine nations attended. Also in 1972, Georgetown was the scene of a Caribbean cultural festival. Diplomats in Georgetown noted that “Burnham’s government lost no opportunity to cash in on Guyana’s brief moment of glory.”

80 Guyana could scarcely afford such expenditures on international affairs.

Burnham’s conception of cooperative socialism and nonalignment ultimately and ironically led him into the Communist camp. Burnham committed every sin that U.S. officials had warned that Jagan was capable of carrying out. He denounced U.S. economic aid and evicted Peace Corps volunteers from the country. By the mid-1970s, he had opened diplomatic and economic relations with the Soviet Union, Eastern European nations, the People’s Republic of China, and Fidel Castro’s Cuba. U.S. diplomats reported that Guyana became “inundated” with foreign Communists, including operatives from the militant Communist nations of Bulgaria, East Germany, and North Korea.

81 Burnham also accepted economic aid from the Communist nations. He traveled to Beijing and Havana and hosted Fidel Castro in Georgetown. He even flew to a conference in Algeria with Castro on Castro’s airplane. In 1976, he began to permit Cuban airplanes to refuel in Guyana on their way to transporting Cuban troops to Angola. He also denounced the 1983 U.S. invasion of the Caribbean island of Grenada. He spoke of the virtues of Marxism-Leninism.

82 The U.S. man in Georgetown had seemingly created the only Marxist state in South America, although a cynic might have assigned the label “kleptocracy” rather than “Communist” to characterize Burnham’s misrule. When asked about his apparent change in political philosophy, Burnham protested that “I did not try to fool the United States government or anybody,” adding that he had always been a socialist.

83Analyzing how the United States reacted to Burnham’s antics is beyond the scope of this study. In any case, documentary evidence concerning U.S. foreign policy for the 1970s and 1980s remains unavailable for research, although U.S. diplomats who served in Guyana have recalled their experiences in oral histories. The United States did not make a sustained effort to destabilize the Burnham regime. As evidenced by U.S. efforts against the Chilean Salvador Allende (1970-73), the overthrow of the New Jewel Movement in Grenada, and the relentless 1980s campaign against the Sandinistas of Nicaragua, U.S. officials had not renounced the policy of confronting leftist movements in the Western Hemisphere that they perceived as endangering U.S. national security in the Cold War. But U.S. officials forecast that an unseating of Burnham would lead to Cheddi Jagan and the PPP taking power. Ambassador Clint A. Lauderdale, who served in Georgetown from 1984 to 1987, deplored Burnham and concluded that U.S. national security interests would not be threatened by the democratic election of Jagan. Nonetheless, Ambassador Lauderdale noted that Jagan, with his long-standing Communist affiliations, presented a “public relations” problem for U.S. policymakers. They worried that the U.S. public would react strongly to another political leader in the Western Hemisphere who accepted the label “Communist.” Burnham continued to play on these fears. During the last fifteen years of his rule, Burnham rarely spoke to U.S. officials. When he did, he told them not to “forget when you evaluate my regime that my opposition is the Communists.”

84Jagan confirmed long-standing U.S. suspicions when, in June 1969, he attended the World Conference of Communist and Workers Parties held in Moscow. Jagan enrolled the PPP as a pro-Soviet Communist party. At the conference, Jagan admitted, however, that he came to his open embrace of the international Communist movement only after both the Conservative and Labour governments of the United Kingdom had betrayed the PPP.

85 Thereafter, Jagan did not wield significant influence at home or abroad. He counseled his party against violence, recognizing that resistance would give Burnham the excuse to massacre Indians. He continued to trumpet his belief in parliamentary democracy, having his party compete in Burnham’s sham elections. At times, Jagan and PPP legislators boycotted the Guyanese legislature, protesting Burnham’s latest outrage. On the other hand, Jagan supported Burnham’s nationalization of the economy, suggesting that it was putting Guyana on the path to true socialism.

86Although U.S. policymakers during the Cold War declined to call for the free elections in Guyana that Cheddi Jagan would inevitably win, U.S. presidential administrations, especially the Republican governments of Richard M. Nixon, Gerald R. Ford, and Ronald Reagan, expressed disdain for Forbes Burnham in a variety of ways. In 1971, the Nixon administration cut off economic aid to Guyana. The administration’s ambassador in Georgetown, Spencer King, referred to Burnham as a “racist demagogue” in conversations with diplomatic colleagues.

87 Henry A. Kissinger, Nixon and Ford’s secretary of state, pithily dismissed Guyana as being “invariably on the side of radicals in Third World forums.” Kissinger sent tough messages to Cuba about its adventures in Africa through Guyana, knowing the two nations shared a close relationship. Kissinger also apparently asked Venezuela and Brazil to threaten Guyana in 1976 when Burnham began to assist Castro with his African adventures.

88 The Jimmy Carter administration tried to improve relations, offering economic aid on humanitarian grounds to the beleaguered nation.

89 After the Jonestown tragedy of 1978, the Carter administration withdrew its interest in Guyana. The Reagan administration closed down the U.S. economic aid program, with the Burnham regime again ridiculing U.S. assistance.

90 Beginning with the Carter administration, the United States began to issue annual human rights surveys. These reports documented the political oppression and human misery of Guyana.

91U.S. policy toward Guyana underwent a remarkable change during the period from 1990 to 1992. With the breaching of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1991, any lingering fear that Guyana could become a Cold War battleground had obviously dissipated. U.S. policymakers could now focus on the appalling misery of a little country with a minuscule population in an isolated, largely uninhabitable region of the Western Hemisphere. By 1990, the country’s economy was prostrate. The production of sugar and bauxite had fallen by more than 50 percent since 1970. Electrical output had similarly declined by 50 percent. Guyana had a staggering external debt of $1.5 billion. Its currency was virtually worthless. With a per capita income in 1991 of only $290, Guyana had the lowest per capita income in the Western Hemisphere. International agencies, like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, informed PNC leader Desmond Hoyte that Guyana could expect no financial help unless it pursued a course of political and economic liberalization. Nongovernmental organizations, like the Caribbean Conference of Churches, similarly pressured Hoyte to hold free elections. The George H. W. Bush administration also promoted free elections. With the Cold War over, democratic values had supplanted anticommunism as the driving force in the U.S. approach to its southern neighbors. The United States no longer embraced anticommunist military dictators like General Augusto Pinochet of Chile (1973-90). The Bush administration further hoped that a policy of democracy would isolate the region’s last Communist, Fidel Castro of Cuba.