Chapter Three

The Battle in Hanoi for the Tet Offensive

These traitors have sowed dissension within the Party and undermined the unity of our army. Their underhanded activities are evident. Their purpose is to organize a faction to oppose our Party, the Workers’ Party. . . . They assumed that in the last 20 years our Party lines and policies have been affected by dogmatism and that our plan of opposing the U.S. for national salvation is shortsighted.

—Le Duc Tho1

On 5 July 1967, one day before he was set to return South, COSVN Commander General Nguyen Chi Thanh had lunch with an ailing Ho Chi Minh. Lingering at his car before leaving, General Thanh worried it would be the last time he would be able to set eyes on the aged leader. Ho was thinking along the same lines. Asking Thanh to convey a message to the southern revolutionaries since he might not live to see victory and reunification, Ho wanted them to know that the South was always in his heart. Moved by Ho’s parting words, Thanh made his way to his next appointment with his sometime nemesis, General Vo Nguyen Giap. On that day, however, the two generals seemed to get along well enough as they strolled around beautiful West Lake with their wives and later dined together without their wives at Giap’s residence. After a hearty feast with heavy drinking—a proper sendoff meal before returning to the front—Thanh stumbled home around 11:00 P.M. to find his wife and four children awaiting his arrival.

That humid July night was made even more unbearable when an electricity outage hit Thanh’s Ly Nam De neighborhood to the west of the Old Quarter in central Hanoi. After putting his kids to bed and telling them to behave in his absence, Thanh took an ice-cold bath to cool off, and around 1:00 A.M., he went to bed. An hour later, he woke his wife, Cuc, telling her that he felt as if water was rushing through his body. When Thanh’s bodyguards rushed into the house to take him to the hospital, the proud general refused to be carried out and walked himself to the car. The show of strength belied his condition. General Thanh was pronounced dead of a heart attack at 9:00 A.M. on 6 July 1967 at Military Hospital 108. At the funeral the next day, as Ho Chi Minh moved everyone to tears by bidding an emotional farewell to the general who would be unable to deliver his message to the South, those gathered could not understand how the seemingly healthy general had died so suddenly. To Huu composed a poem that he read at the funeral, capturing the disbelief of those attending the wake with his first line, “Oh Thanh, are you really gone?”2 Waiting until nightfall, when American bombs stopped falling, Party and military leaders held Thanh’s burial service under the cover of darkness at Mai Dich Military Cemetery, but they did not lay to rest their doubts and suspicions.3

A few weeks after the general’s funeral, Hoang Minh Chinh, the Party theoretician who found himself on the wrong side of the internationalist debate, was arrested by internal security forces. Upset at what he saw as the hijacking of VWP policy by South-first militants since the early 1960s, Chinh had called on North Vietnamese Party leaders to heed Soviet advice and engage in negotiations with the United States to end the destructive war. At the start of the wet season in July 1967, security forces silenced Chinh by arresting him along with several other academics and journalists as typhoon rains—and American bombs—pummeled Hanoi. Although large segments of the Hanoi populace, as with other major cities in North Vietnam, had been evacuated to the countryside as a result of American bombing, enough “treasonous” elements still managed to thrive in the capital to attract the attention of the police state. For the remainder of the year, as the military plans for the 1968 offensive took shape in the corridors of Party power, security forces in Hanoi rushed into people’s homes in the dark of the night, kicked down doors, and incarcerated hundreds of supposed traitors.

General Thanh’s death and Hoang Minh Chinh’s arrest in 1967 set the stage for Hanoi’s greatest strategic victory and gravest tactical defeat: the Tet Offensive. Although the 1968 surprise attacks represented a major turning point in the Vietnam War, much of North Vietnam’s decision making surrounding the offensive remains unclear. Hanoi’s strategy deliberation, which took place from the spring of 1967 to the beginning of 1968, is still shrouded in mystery.4 In the absence of official documents relating to the Tet Offensive, many debates still abound regarding the origins, the timing of key decisions, and the aims of what the North Vietnamese leadership called the General Offensive and General Uprising (Tong cong kich, Tong khoi nghia, GO-GU). The current Vietnamese and Western historiography offers only limited answers.5 According to David Elliott, “There is a curious reticence among Party and military historians about the decision-making process that led to the Tet Offensive, even decades after the event.”6

Contemporaneous and postwar studies published in Vietnam assert that the military losses and political setbacks suffered by the United States and the RVN in 1966 and 1967 presented a key opportunity for the communist forces to undertake a major offensive in 1968.7 Indeed, Vietnamese scholarship cites the inability of the United States to achieve its projected speedy victory over the insurgency as the only factor in Tet decision making.8 In this view, the failure of Washington’s war of attrition9 and its bombing campaigns over North Vietnam,10 compounded by the growing political disillusionment with the war in the United States, prompted the leadership of the VWP to shift the “revolution to a new stage, that of decisive victory.”11 With the U.S. presidential elections approaching in 1968, Hanoi made the decision in the spring of 1967 “to quickly prepare on all fronts to seize the opportunity to achieve a large victory and force America to accept a military defeat.”12 According to Vietnamese scholars, then, the Tet Offensive was strictly a result of the Party leadership’s astute decision to exploit the favorable conditions, both militarily and politically, arising from the enemy’s failing war effort in the South.13

Conspicuously absent from the literature is any mention of conditions within the DRV that played a part in the Tet strategy deliberation. To be sure, there were grave domestic and international concerns weighing on the minds of Le Duan’s “War Politburo” as it devised its military plans in 1967.14 After two costly years of war against the world’s greatest superpower ground down to a stalemate, internecine Party struggles reached a feverish pitch in Hanoi. Even though Le Duan held firm control over the VWP leadership, his dogged persistence in winning the war militarily through big-unit warfare, rather than initiating negotiations or reverting to protracted guerrilla struggle, brought about challenges to his authority not only from rival Politburo members but also from Hanoi’s allies, who coupled much-needed military and economic aid with unwanted and often conflicting advice. This chapter looks at the “incremental, contested, and improvisational” Tet strategy deliberation in 1967, which, like earlier decisions, took into account not only the U.S.-RVN war effort but also VWP politics and the Sino-Soviet split.15

FROM THE REVISIONIST ANTI-PARTY AFFAIR TO THE HOANG MINH CHINH AFFAIR

In retrospect, the direction of the war could have gone in several directions in 1967; the decision to proceed with the Tet Offensive was far from written in stone at the beginning of the year. In January, the Party leadership adopted a military-political-diplomatic strategy, codified in Resolution 13, that appeared to offer a solution, since it split the difference between various factions.16 The resolution not only advanced the diplomatic struggle but also called for a “spontaneous uprising in order to win a decisive victory in the shortest possible time.”17 A few days after the passage of the resolution, DRV minister of foreign affairs and Politburo member Nguyen Duy Trinh underlined the diplomatic aspect of the strategy by indicating that if the United States stopped bombing unconditionally, talks could begin.18 To the dismay of the North-firsters and pronegotiations factions as well as the Soviet allies, Le Duan had secretly decided that peace talks could not begin until communist forces had fulfilled the other aim of Resolution 13: a “decisive victory” on the battlefield. By launching a major military action against the South Vietnamese forces during the upcoming U.S. presidential election year, Le Duan hoped to topple the Saigon regime, forcing any subsequent negotiations with the United States to reflect a victorious DRV over a vanquished RVN. Le Duan only had to look at Ho Chi Minh’s marginalized position in the Party leadership since the French-Indochina War to be wary of premature negotiations.

Like most issues concerning military strategy, however, Party and military leaders were divided on how best to achieve a “decisive victory.” Mirroring the debates taking place in Washington at the same time, the VWP leadership could not agree on the most effective way to break the stalemate. While Ho Chi Minh, General Giap, and Chinese leaders urged caution by preparing communist forces for a protracted war, Le Duan and his hawks strove for total victory through an ambitious and risky large-scale offensive aimed at the cities and towns of South Vietnam. Not only had the first secretary predicated his power on the southern cause in 1959-60, he became personally identified with the GO-GU strategy used in 1963-64. When his go-for-broke strategy not only failed to bring a clear victory but also triggered American military intervention, Le Duan bided his time until he could redeem his military approach. In 1967, Le Duan again became convinced that a concerted series of attacks on the urban centers of South Vietnam could bring total and complete victory.

In reality, Le Duan’s costly strategy for victory was just another “roll of the dice.”19 Nevertheless, he succeeded in getting the Party leadership to approve plans for another GO-GU with the passage of Resolution 14 in January 1968, once again relying on his apparatchiks and utilizing the powers of his police state.20 The first secretary and his militant faction thus emerged victorious in the struggles that gripped the leadership in 1967; the resultant Tet Offensive plans were a major blow to both domestic opposition and foreign obstruction. In order to understand the evolution of Party policy from Resolution 13 to Resolution 14, it is necessary to understand not only the battle waged in South Vietnam but also the one unfolding on the streets of Hanoi.

The Revisionist Anti-Party Affair—which has also been referred to as the Hoang Minh Chinh Affair, in recognition of its first and most vocal victim—reached its dramatic conclusion three years after it began.21 Although the affair began as an internal Party debate over the international communist line, it ended as a means for Le Duan to launch the 1968 Tet Offensive without any obstructions. Prior to his incarceration in the summer of 1967, Hoang Minh Chinh had circulated a controversial 200-page report titled Ve chu nghia giao dieu o Viet Nam (Dogmatism in Vietnam) that criticized the lack of openness and democracy in the Party.22 Not only was Chinh suspected of treasonous activities with this publication, he was accused of being part of a larger network of saboteurs including cabinet ministers, high-ranking PAVN officers, CEC members, National Assembly delegates, government leaders, distinguished veterans, intelligentsia, journalists, doctors, and professors who conspired to overthrow the government.23 As spy fever spiked in the capital, the Secretariat kept secret these arrests as it assessed its Instruction 145 (Chi thi 145), promulgated by the Party in early March, which monitored any espionage activities and their effect in the North.24

The purges occurred in three waves. On 27 July, the Bao Ve rounded up Chinh as well as a small group of professors and journalists. In mid-October a second wave of arrests began. The security forces apprehended more Party members, but this time, the arrestees included more high-ranking and noteworthy figures, such as the well-known generals of Vo Nguyen Giap’s staff, Le Liem, Deputy Defense Minister Dang Kim Giang, Deputy Chief of the General Staff Lieutenant-General Nguyen Van Vinh, and the General Staff’s military intelligence chief, Senior Colonel Le Trong Nghia, as well as Ho Chi Minh’s former secretary, Vu Dinh Huynh. The third and largest wave of incarcerations, which took place on 25 December, involved Party members and non-Party professionals, including Vu Dinh Huynh’s son, Vu Thu Hien, who later wrote their memoir based on the injustices they underwent.25 With the testimony of Vuong Quang Xuan, a captain of the North Vietnamese Army and intelligence agent who defected to the RVN in early 1969, the outlines of the purge became known early on:

In late 1967 and early 1968 several hundred people, including high-ranking party and government officials, were arrested for being against Lao Dong party war policies and plotting the overthrow of Ho Chi Minh. . . . The party had known of the group for a long time, and Le Duc Tho supposedly had talked with [Hoang Minh] Chinh and other members of the group about their beliefs before they were arrested. . . . A bulletin written by Chinh had been seized and was considered proof of his treason. The bulletin took a position against Resolution Nine which stated that the situation in South Vietnam was now favorable for the use of military means to overthrow the government of South Vietnam, and that the party would not repeat, not use political means only to achieve victory. It asked for the full support of all North Vietnamese cadres and people in this effort. . . . Chinh’s bulletin opposed North Vietnamese military participation in the liberation of South Vietnam.26

The scope of the perceived threat to national security and the shift from a secret investigation begun in 1963 to an overt one by 1967 resulted in the mobilization of greater manpower for Le Duc Tho and Tran Quoc Hoan.27 In addition to the various intelligence subcommittees and the personnel and staff under their direction since 1963, Le Duan’s security apparatus and police state burst at their seams by 1967 with additional cadres drawn from regional committees, the navy, as well as the Communications and Engineering Departments.28 In July, Minister Hoan gave a speech on how the Cong An were able to escape the pernicious influence of modern revisionism that had infected other cadres.29 On 30 October, the Standing Committee of the National Assembly presided over by Truong Chinh promulgated a decree setting forth the terms of punishment for treason, espionage, and transmitting state secrets. By the end of the year, Le Duc Tho circulated two reports that warned of a plot in their midst. Although the suspects arrested were not formally accused until 1972,30 Tho wrote the following report in late 1967:

These traitors have sowed dissension within the Party and undermined the unity of our army. Their underhanded activities are evident. Their purpose is to organize a faction to oppose our Party, the Workers’ Party. They have deliberately made inaccurate analyses, partial critiques, and mischievous evaluations in the Politburo with the intention of fomenting friction between Party leaders. They have gained the allegiance of a number of high-ranking cadres of various ministries, even those of a foreign country. They have sought methods of stealing our confidential documents. They have taken advantage of our cadre’s carelessness to collect classified information on our military plans, economic projects, and on foreign aid provided to us by friendly countries for our national salvation against the U.S. aggression. They have tried to hinder our counterattack of the enemy. They have tried to prevent COSVN from implementing Resolution 9. They assumed that in the last 20 years of our Party lines and policies have been affected by dogmatism and that our plan of opposing the U.S. for national salvation is shortsighted.31

The alleged traitors were imprisoned in central Hanoi at Hoa Lo, known to Americans as the “Hanoi Hilton.”32

It is unlikely that these individuals posed an actual threat to national security. Although the Revisionist Anti-Party Affair had its origins in the controversial 1963 plenum and would have legal and political repercussions for the DRV beyond 1968 and even 1975, the immediate rationale for the arrests in 1967 rested squarely on the Politburo’s choice of tactics and strategy for the Tet Offensive.33 Nothing else would have prompted a purge of such proportions. By this point, theoretical arguments couched in seemingly dense but innocuous Marxist-Leninist terms actually signified intense debates regarding the direction of the war in the South.34 Under Le Duan’s leadership, the decision to forgo substantive negotiations and to pursue a “decisive” military victory by launching large-scale attacks on the cities and towns across South Vietnam in pursuit of a GO-GU was highly controversial and hotly contested within the VWP. By integrating the timetable regarding decision making from above and the arrests on the ground, the pieces of the Tet puzzle begin to fall into place, revealing that as plans for the military offensive grew more ambitious, so too did the scope of the arrests.

As was the case when Le Duan led the Party to elevate the political struggle to armed conflict in 1959 and to go for broke in 1963, his ability to promote the adoption of the GO-GU strategy in 1967 must be situated at the intersection of Hanoi’s foreign and domestic policies and be seen as a response to the military picture in South Vietnam or the political situation in the United States. In doing so, the Revisionist Anti-Party Affair and the Tet decision-making process can be understood on three interrelated levels: (1) the DRV’s policy of equilibrium in the Sino-Soviet split; (2) personal power struggles in the Hanoi Politburo; and (3) political repression in the VWP. Drawing on their survivalist modes of leadership, garnered first during their experiences in the Mekong Delta battling multiple rival factions in the 1940s and 1950s and then strengthened during their steady climb to power in the Red River Delta in the 1960s, Le Duan and Le Duc Tho resorted to intrigue, double-dealing, and intimidation so that “darkness descended in midday” for hundreds of Hanoians in 1967.35

SIGNALING THE ALLIES

For three years, Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and other leaders in Beijing watched with consternation as North Vietnamese leaders seemingly moved away from the Chinese sphere of influence and into the Soviet one.36 Recalling the early days of the French-Indochina War and even the beginning of Vietnam’s war for reunification, when Moscow could not be bothered with the events in Indochina, Chinese leaders could not understand how the North Vietnamese were unable to see through the present Soviet ruse. According to Beijing, support from the revisionist Soviet regime always came with strings attached. Chinese leaders were convinced that Leonid Brezhnev, Alexei Kosygin, Nikolai Podgorny, and their cronies in the CPSU would sell out the Vietnamese revolution to the Americans when this served Soviet interests.

Although Moscow’s military and economic aid to the DRV appeared in 1967 to be on the verge of eclipsing China’s, Beijing leaders could take solace in two reasons the North Vietnamese remained beholden to the PRC: not only did Beijing control transport logistics, but there were also hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops in North Vietnam, even if they were only set to work on building roads and infrastructure.37 Mao and other Chinese leaders felt they could make a few demands of their Vietnamese allies. They wanted Hanoi to reject both Soviet advice to engage in negotiations and Russian-style warfare as well as remain skeptical of all forms of Moscow’s support. Beijing hoped instead to see Vietnamese leaders apply Chinese revolutionary strategy and prove to the world that Mao, rather than Brezhnev, could lead internationalist forces to defeat the world’s leading neoimperalist power. To their dismay, however, the North Vietnamese not only gladly accepted Soviet aid and training as well as offers of technical assistance but also seemed to be heeding Soviet advice and mimicking Soviet warfare.

Le Duan and his colleagues in the VWP Politburo were all too familiar with Beijing’s anti-Soviet thinking, and they tried their best to allay Chinese fears of a supposed VWP tilt toward the CPSU. In early April 1967, General Giap and Prime Minister Dong traveled to Beijing, where they praised Chinese military influence on Vietnam’s revolutionary struggle. “Some of the strategies we are adopting on the battlefield in South Vietnam,” Dong informed Zhou Enlai, “follow what you suggested to us in the past.”38 At a subsequent meeting, Giap said to Mao Zedong, “In our fighting against the Americans, we always remember your words: try to preserve and develop our forces, steadfastly advancing forward.” After lavishing their hosts with praise, Dong and Giap informed their allies that Party and military leaders in North Vietnam had agreed to introduce “new” elements into their “strategic principle” for 1968.39

Despite such reassurances, however, Mao feared that the “new” elements in Vietnamese military planning would mean adopting a Soviet model of warfare, which included large-scale offensives aimed at urban centers in an attempt to win a quick victory. Such a strategy would increase North Vietnamese dependence on Russian aid and weaponry, and perhaps even push Hanoi further into the Soviet orbit. “We have a saying,” Mao stated in his characteristically allegorical manner, “‘If you preserve the mountain green, you will never have to worry about firewood.’ The U.S. is afraid of your tactics. They wish that you would order your regular forces to fight, so they can destroy your main forces. But you were not deceived. Fighting a war of attrition is like having meals: [it is best] not to have too big a bite.”40 Although General Giap inwardly agreed with the Chinese leader regarding the necessity to wage protracted war at this juncture in the war, he was powerless to stop Le Duan and General Thanh from taking a big “bite.”

Although the April 1967 meetings reveal that Beijing approved of Vietnamese plans to escalate the war, Mao was right to be wary of North Vietnamese military aims for 1968. When the delegation returned to Hanoi in the late spring, planning for the Tet Offensive began to take the form of an ambitious nationwide attack on major cities and provincial towns—a move the Chinese would later consider premature and a reflection of the Soviet proclivity for urban warfare. In May and June, the VWP leadership essentially rejected Mao’s doctrine when it assessed the military picture for 1968 and concluded that guerrilla war alone could no longer remain the guiding principle for the resistance forces in the South.41

Although the Chinese were concerned about the rising Soviet influence on Vietnamese military strategy, they were relieved that the Hanoi Politburo still rejected Soviet advice to enter negotiations. Arriving later in the game than the Chinese and possessing no clear-cut allies in the Politburo, the Soviet embassy in Hanoi under Ambassador Ilya Scherbakov tried to cultivate contacts and allies among VWP officials who had studied in Moscow in order to increase the Soviet Union’s influence in North Vietnam and promote its negotiations agenda.42 The culmination of Moscow’s meddling occurred in late June when Premier Kosygin met President Johnson in Glassboro, New Jersey, with private reassurance from Prime Minister Pham Van Dong that if the United States stopped bombing, negotiations could begin.43 Between Dong’s private reassurance and Foreign Minister Trinh’s public statement earlier in the year, Ambassador Scherbakov and his bosses in Moscow believed that their influence had now reached beyond midlevel VWP officials all the way up to the Vietnamese Politburo.

As the Soviets increased their efforts to initiate peace talks between Washington and Hanoi, thereby bolstering the moderates in the Party as well as the Politburo, Le Duan and his faction launched a preemptive strike against these forces and their Soviet benefactors. In doing so, Le Duan sent a thinly veiled message to Moscow: the DRV would not be pressured into negotiations. Essentially, the Revisionist Anti-Party Affair signaled to the Soviet embassy in Hanoi that the arrests of its “eyes and ears” in the VWP also meant the end of Moscow’s hopes to push forward its agenda.44 Charged with “gain[ing] the allegiance of a number of high-ranking cadres of various ministries, even those of a foreign country,” and then passing on state secrets and classified information, the arrestees were basically guilty only of maintaining close ties with the Soviet Union. The Soviet embassy in Hanoi understood the message loud and clear: exasperated reports to Moscow indicated that North Vietnamese leaders were no longer interested in pursuing negotiations.45

The arrests of pro-Soviet officials who had “assumed that in the last 20 years [the] Party lines and policies have been affected by dogmatism” were intended as much to placate the Chinese as to deter the Soviets.46 These so-called traitors had passed information to the Soviet embassy in Hanoi and abroad regarding the extent of Chinese activity and aid to the DRV.47 Their arrests signaled to Beijing that the VWP would not fall into the hands of a pro-Moscow group. The victims of the 1967 purge were sacrificed in order to maintain North Vietnam’s policy of neutrality and equilibrium in the Sino-Soviet split. As Hanoi’s juggling act became trickier to maintain, the arrests sent a clear message to the allies without posing substantial risks to North Vietnam’s diplomatic relations.

POWER STRUGGLES IN THE POLITBURO

The arrests were also meant as unveiled threats to high-ranking members of the Politburo who had dared to challenge Le Duan’s authority. By 1967, the first secretary identified multiple figures in the Party and military leadership who stood in the way of his goal of redeeming the GO-GU strategy. By arresting the loyal subordinates of their rivals, Le Duan and Le Duc Tho were able to undermine the positions of their detractors without disturbing the illusion of a unified leadership in Hanoi necessary to guide communist forces to victory.

During his colonial education, Le Duan must have stumbled across Georges Clemenceau’s famous adage that war is too serious a matter to entrust to military men. Although it is difficult to assess the nature of civil-military relations in the DRV during the Vietnam War, there is tentative evidence that tension existed between Party leaders and the military brass. As high-profile commanders who possessed the allegiance of men both north and south of the seventeenth parallel, Nguyen Chi Thanh and Vo Nguyen Giap were extremely popular generals. Their popularity may have been a double-edged sword, since it inspired the jealousy of the first secretary. Although there is no proof that Le Duan had anything to do with the mysterious death of General Thanh—other than a postwar allegation by the defector and Politburo member Hoang Van Hoan in his memoirs—the circumstances surrounding Thanh’s death on 6 July 1967 have produced much speculation.48 At the time, Western observers believed that he had been killed in B-52 attacks.49 The main source of Hanoi gossip after the war, Bui Tin, claims that General Thanh died the day before he was to return to the South via the Ho Chi Minh Trail after suffering a heart attack.50According to Thanh’s widow, Nguyen Thi Cuc, her husband became inexplicably ill after a full day of meetings and sumptuous meals, though she abstained from alleging poisoning.51

Whether due to natural or other causes, Thanh’s death took place during an extremely important juncture in the planning for the 1968 offensive. Two months before, Thanh had convened COSVN’s Fifth Plenum and confirmed his long-held position in various speeches that communist forces would maintain the strategic initiative by attacking enemy forces head on, rather than by reverting to defensive guerrilla war, and thus would score a decisive victory in 1968. He did not, however, elaborate a specific military strategy.52 In June, Thanh’s comrades in the Politburo recalled him to Hanoi in order to report on the military situation in the South. After three long years on the war front, General Thanh left the South on what would be his last journey. While in Hanoi, he ordered the Combat Operations Department (Cuc Tac chien) to “continue, in a systematic matter, to brainstorm the strategic direction and objectives that would lead to a decisive victory.”53 During the course of his stay in the DRV capital, General Thanh heard disparate viewpoints from members of the Politburo subcommittee for military affairs, the Party’s CMC, and the PAVN General Staff. While some members of the Politburo were dubious that communist forces could achieve a decisive victory against American forces in 1968 through large-scale battles, Le Duan adopted a more militant position:

It is impossible for the United States to maintain its current troop level, to expand the war, or to drag it out. The Americans have no option other than employing greater military strength. As such, we have to counter their strategy by ratcheting up our war effort to a new level—one that the Americans will not be able to endure, leading to their military defeat and their political isolation. If we can accomplish this, the Americans will surely have to withdraw from South Vietnam. Thus, I say we increase our military attacks so we can then seize the initiative to advance the diplomatic struggle in order to use world public opinion against the imperialist Americans and their bellicose puppets.54

In other words, Le Duan believed he could find America’s breaking point. Resurrecting his bold strategy that had failed to win the war in 1964, Le Duan was convinced that the GO-GU would achieve that sought-after decisive victory in 1968. The Da Nang uprisings in 1966 offered Le Duan indisputable proof that the cities and towns were tinderboxes for general insurrection, which a spectacular military victory could spark.55 Although the majority of the military leadership, led by General Giap, believed that revolutionary forces were not yet ready to launch large-scale attacks aimed at the cities and towns of South Vietnam, Le Duan was willing to take the chance in 1968. Whether General Thanh, who had staked his military credentials on big-unit warfare in order to maintain the initiative and uphold troop morale, disagreed with Le Duan, we will never know. Most likely he did not, since General Thanh was a hawk who had predilection for sending troops into battle and took pleasure in proving General Giap wrong.56

After weeks of contentious debate over military strategy, General Thanh scheduled his return to the front lines. Although Thanh’s death the day before he was set to leave was a clear loss for the militants, Le Duan may have concluded that the peasant general had already served his purpose by maintaining the strategic initiative in the South and thwarting Giap in the North. Had he lived, Thanh could have either blocked Le Duan’s military strategy for 1968, if they had disagreed, or threatened to eclipse the first secretary if the upcoming 1968 offensive proved successful. Despite the rising death toll and the public debate with Giap, Thanh’s popularity rose in the South, possibly prompting comparisons in Le Duan’s mind with the legendary Nguyen Binh of the French-Indochina War. Regardless of the cause of Thanh’s death, Le Duan may have stood to gain from his premature demise during the planning stages for 1968.

Le Duan’s personal animosity toward Vo Nguyen Giap is slightly better documented. The “comrades Le” continued to sideline Giap and saw to it that the general wielded significantly less power in the struggle against imperial America than he had in the war against colonial France.57 With General Thanh’s death, their main counterweight to Giap was gone, prompting the impetus for a preemptive strike against the popular general, who had objected to Le Duan’s urban-centered plan for the upcoming offensive. Although Giap had agreed with the hawks that revolutionary forces had to strive for some sort of “decisive victory” in 1968, the general expressed doubts that any offensive should begin with the cities and towns of South Vietnam. At the 14-16 June 1966 meeting of the Politburo subcommittee for military affairs and the Party’s CMC, at which Le Duan, Le Duc Tho, Pham Hung, and even General Thanh were present, Giap had agreed with his comrades that revolutionary forces must fight large-scale battles, but, he warned, “it was necessary to build up to attack on the cities.”58 “By mid-1967, although a number of revolutionary bases, commando and crack troop units had been deployed in cities and suburbs,” one Vietnamese historian claimed, “no one could imagine a general offensive all over South Vietnam against the cities and towns, particularly when the U.S. war efforts were reaching a climax.”59

With Thanh dead and Giap in disagreement, Le Duan needed a more pliant general to implement his risky military strategy. Vietnam expert Merle Pribbenow portrays the genesis of the 1968 Tet Offensive as a Faustian bargain between Le Duan and Senior General Van Tien Dung. Dung was born in 1917 to a middle peasant family from Ha Tay province, just south of Hanoi. Unlike most of his comrades in the senior leadership, Dung was actually a proletarian. As a young worker in the Cu Chung textile mills, Dung became openly involved in revolutionary activities, joining the ICP during the Popular Front period in the fall of 1937. Arrested on the eve of the Second World War, Dung escaped from a colonial prison a few years later and quickly climbed the communist ranks in Tonkin. During the French Indochina War, Dung became head of the Military Political Department, a precursor to Thanh’s army watchdog outfit, the GPD, particularly for the Viet Bac region, which began to see most of the action after 1950. Friction between Dung and Giap might have arisen during this period, since Dung was in charge of policing Giap’s troops, and probably came to the fore when Dung replaced Giap’s friend Hoang Van Thai as PAVN chief of staff a little while later. Nonetheless, in 1954, the intellectual and the worker had to put their differences aside to carry out the siege at Dien Bien Phu. At the start of the southern war, Dung was promoted to senior general, elected to the CEC and to the Politburo as an alternate member, and served under Giap on the National Defense Council after the 1960 Third Party Congress.60

Seven years later, however, Dung seized an opportunity to advance his career after Thanh’s death and at his boss’s expense. Playing on Le Duan’s desire to promote his brand of military offensive, Dung requested a private meeting with Le Duan behind General Giap’s back. At their meeting, the ambitious Dung expressed support for the first secretary’s position that revolutionary forces had no choice but to foment a general uprising in the towns and cities of South Vietnam even though communist soldiers did not possess a clear military advantage over enemy troops in urban centers. Although he more likely agreed with his boss, Giap, and fellow military commanders that communist forces were not yet ready to lead the masses to the final stage of people’s war and to ultimate victory, Dung was ready to put his own career ahead of the revolution. By ingratiating himself to Le Duan and criticizing the military decision making under the direction of Giap, Dung shrewdly positioned himself as a replacement for Thanh. Le Duan, recognizing that he now possessed an ambitious new counterweight to Giap willing to do his bidding, promoted Senior General Dung to oversee the new and improved plans for the 1968 offensive.61

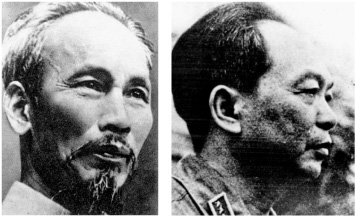

Ho Chi Minh (left) and Vo Nguyen Giap (right) (Anonymous Collection [left] and Douglas Pike Photograph Collection [right], Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University)

Not only was Giap’s fate sealed during the private meeting between Le Duan and Van Tien Dung, but so too were the plans for what would become the Tet Offensive. On 18-19 July, nearly two weeks after Thanh’s death, Le Duan and Dung unveiled their controversial strategy at a high-level meeting including Politburo members and the military brass. While main force units tied down American troops away from urban centers, they advocated, large-scale attacks on the cities and towns of South Vietnam would incite a mass political insurrection to topple the puppet regime in Saigon. Their strategy met immediate resistance from the assembled group of Party and military leaders, the most powerful of which came from none other than Ho Chi Minh. In his final attempt to exert authority over the revolution that he only symbolically led, Ho went on the attack. First, the aged leader questioned the “subjectivity” of Le Duan and Dung’s plans, intimating that perhaps the first secretary and his senior general were being unrealistic and overly optimistic in their goals for the upcoming offensive. The chairman then urged caution for the upcoming offensive. Although the Party and military were in agreement that the forces could attempt a decisive victory, they must prepare for a protracted war. As such, Ho resurrected General Giap’s position, the “need to expand guerrilla warfare” over sole reliance on big-unit warfare.62

Despite Ho’s sensible advice, Le Duan brushed aside this challenge to his command by ordering Dung to continue drafting the military plans based on large-scale attacks on urban centers. While Dung worked out the military details in Hanoi, Le Duan promoted Pham Hung to replace Thanh as head of COSVN. In August, Hung successfully completed what would have been Thanh’s journey to the South, carrying not only the outlines of Le Duan’s plans for an urban-centered offensive, but also the mandate that southern revolutionaries carry them out without question.63 When it became clear that the upcoming 1968 offensive clearly bore Le Duan’s GO-GU imprint, Giap left for Eastern Europe and did not return until well into 1968.64 The defeated Ho Chi Minh followed suit and left for Beijing to convalesce, though he apparently never fully recovered from what had ailed him in 1967.

SPY FEVER IN THE POLICE STATE

Although the purge indirectly served international purposes and became a proxy battle for Politburo members, it held very real ramifications for political life in Hanoi. While moderate Politburo leaders fled North Vietnam, Le Duan and Le Duc Tho removed any vestiges of Ho and Giap’s influence in the lower rungs of the Party and thus paved the way for the adoption of the Tet Offensive strategy. Soon after the pivotal mid-July meeting, Le Duan and Tho applied their brand of ruthless revolution, culled from their dangerous days in the Mekong Delta, to the war-weary and bomb-saturated Red River Delta. The Revisionist Anti-Party Affair, begun three years earlier at the controversial 1963 plenum, reached its dramatic climax with the arrest of its first victim, Hoang Minh Chinh, on 25 July 1967, and ended only with the passage of Resolution 14 giving the go-ahead for the Tet Offensive.65

With the escalation of the air war over North Vietnam, Le Duan’s police state placed the nation on high alert and declared a state of emergency. Minister of Public Security Hoan’s tireless speeches and promulgations whipped up paranoia, creating spy fever as bombs rained down on the North. Hoan warned the ministry’s staff and the security forces to be on guard against neoimperialist use of intelligence and espionage operations to instigate coups or incite “peaceful evolution.” The United States conducted nefarious activities in other sovereign countries by unleashing the CIA even in ostensibly pro-American countries such as South Vietnam. At the start of Hanoi’s “bigger war” in 1963, Hoan claimed, the United States sent individual spies into North Vietnam, but by the latter half of the decade it had infiltrated the DRV with commando teams tasked with carrying out acts of sabotage aimed at paralyzing logistics and fomenting insurrection. After the start of Rolling Thunder, the minister said, America redoubled its espionage activities and concentrated on four areas: (1) collection of strategic and tactical intelligence in all sectors of North Vietnamese life; (2) assassination and kidnapping of cadres and civilians to gather intelligence; (3) recruitment of agents to support operations; and (4) psychological warfare aimed at sowing fear and confusion within the DRV.66

Although the DRV foiled most of the South Vietnamese and American plots by 1967, Hoan advocated constant vigilance since the enemy proved very wily and adept. To be sure, the enemy’s sources for information were diverse. The United States was able to garner intelligence through “careless revelation of state secrets in our own propaganda, press, and radio broadcasts,” and at times through superior technology, including reconnaissance aircraft, radar, and electronic intelligence. Moreover, “delegations from capitalist and imperialist” countries, nations that had embassies, consulates, or trade missions in Hanoi, and regional powers such as Laos and Thailand, all supplied information to Washington. For example, Hoan claimed, de Gaulle’s neutralization schemes were plots to buffer America’s defeats in South Vietnam, while Japanese spies and British imperialists used their commercial ties and diplomatic missions to carry out long-term espionage operations for the Americans.67

However, Hoan warned, security forces had to be most wary of “spies hiding inside North Vietnam,” who came from disaffected sectors of society. The minister laid bare these reactionary elements to his security forces, which now possessed the authority to trample North Vietnamese civil rights with impunity: “Currently the enemy still has a number of refuges, places where he can hide to carry out his activities in our society in North Vietnam. These refuges are reactionary elements utilizing the cloak of the Catholic religion; reactionary elements among former members of the puppet government and army; former members of ethnic minority bandit groups and former members of reactionary parties; the former upper classes in ethnic minority areas; former members of the exploitative classes; and those who are dissatisfied with society.”68

Since these elements were either spies directed by the enemy or reactionaries who wanted to establish contact with the enemy, Hoan claimed that “our fight against imperialist spies is intimately linked with the fight against reactionary elements inside our country, and vice versa.”69 In other words, there was absolutely no room for dissent within the DRV; opposition was either proof of espionage or reactionary. Hoan instructed his security forces to first establish the origins of individuals suspected of being spies or reactionaries (i.e., whether they were legally or illegally residing in North Vietnam) and then to detect contradictions in the suspects’ lifestyles (when their spying ran counter to their professional cover). Spies and reactionaries were never capable of maintaining the ruse, Hoan observed, and identifying their inability to function in their cover professions—even more than deciphering their origins—was the key to exposing traitors.

Despite being adept at their alleged cover jobs as successful Party cadres, military officers, lawyers, doctors, and teachers, the suspects of the Revisionist Anti-Party Affair were rounded up by Hoan’s security forces and summarily labeled as traitors. In reality, Chinh and the other Party officials arrested after publicly opposing the war in the South and decrying the mounting repression in the North posed no threat to national security. Instead, their arrests demonstrated that Le Duan’s Politburo would not tolerate any criticism of the southern struggle and the northern revolution and that it would go to any lengths to prevent the leak of war plans or state secrets to allied powers. With the strategy deliberation for the Tet Offensive under way, Le Duan could not allow Chinh and his publication of Dogmatism in Vietnam to go unpunished and his connections with Soviet officials to go unchecked. Since Chinh and other pro-Soviet Party officials had criticized the Party leadership’s refusal to end the costly southern war through negotiations, their opposition to the upcoming 1968 offensive would be even more intense. Based on their challenge to Resolution 9 in 1963, which confirmed Hanoi’s tilt toward Beijing and laid out the GO-GU plans for 1964, these “North-first” moderates would surely object to the resurrection of the same risky strategy for 1968, one that ran counter not only to Soviet advice to seek negotiations and to de-escalate the fighting but also to the VWP’s own Resolution 13 in 1967 that ostensibly advanced the diplomatic struggle.70 Moreover, the architects of the purge incarcerated the vocal antiwar members of the Party in July because they wanted to protect the element of surprise necessary for the Tet Offensive to succeed in the midst of the spy fever that gripped Hanoi.71

In mid-October, the second wave of arrests began—this time of Party members and military officials more high-ranking than those caught in the July purge—as Le Duan and Van Tien Dung continued to forge ahead with their military plans for the 1968 offensive. Including elements of Thanh’s favored big-unit warfare along Khe Sanh, in the mountains of the extreme northwestern corner of South Vietnam and along the DMZ, the Duan-Dung amendments included “big battle” strikes against the cities and provincial towns of South Vietnam to incite a general insurrection.72 Shortly after the Politburo reviewed the revised plans from 20 to 24 October, the Bao Ve arrested Giap’s loyal staff from the Dien Bien Phu campaign, including Lieutenant-General Nguyen Van Vinh and Senior Colonel Le Trong Nghia, who had been active in drafting the 1968 offensive as members of the General Staff and who had briefed the Politburo members at the October meeting. Although the official histories state that Vinh and Nghia presented favorable reports on the likelihood that large-scale attacks would incite a popular insurrection in the cities, the two officers disappear entirely from the historical record after the Politburo meeting, only to appear in the 1990s on the list of arrestees in 1967.73

These October arrestees who had served at Giap’s side claimed that security officials under the control of Le Duan, Le Duc Tho, and Tran Quoc Hoan had hoped to implicate Giap in the Revisionist Anti-Party Affair. When these top military men arrived at Hoa Lo prison, the Bao Ve began to interrogate even Hoang Minh Chinh and the earlier July arrestees regarding any interactions they may have had with the famous general.74

Neither Giap nor Ho were able to fly back to Hanoi to spring their subordinates and staff from jail.75 They thus also forewent an opportunity to voice their opposition to the direction of the Duan-Dung plan during the October Politburo meeting. Perhaps Giap and Ho had finally given up; not only had their objections proven unable to alter Le Duan’s designs, but their continued opposition also kicked the first secretary’s police state into full gear. In fact, the debate surrounding military planning had become so contentious that Le Duan refrained from attending the October meeting as well, leaving Truong Chinh, who had begun to take an avid interest in stamping out the Revisionist Anti-Party Affair, to preside over the Politburo’s deliberations. Even though the members present postponed the approval of the “general uprising” section of the upcoming offensive, citing the absence of key leaders, Le Duan was confident that he had already won the battle for the Tet Offensive.76

The power struggle among these key Politburo members not only prompted a wave of political arrests in Hanoi but also caused a momentary breakdown of military leadership that had disastrous results for the Lunar New Year attacks. “One of the mysteries of the planning for the Tet Offensive,” Vietnam scholar David Elliott writes, “is how much (and when) the lower levels . . . knew about the specific nature and extent of changes that may have taken place in the basic plan between June 1967, its formal transmittal to the South in October 1967, and the final Hanoi Politburo resolution of December 1967.”77 Although indoctrination sessions occurred in the southern theaters prior to October, the emphasis remained on protracted struggle, fighting while negotiating, and taking advantage of local environments. The events of October led to the de facto approval to target urban centers, what one military historian has called “a daring decision of Vietnam indeed because if we had simply considered the balance of military force at that time (October 1967), we would not have taken this audacious decision.”78 Tran Van Tra later criticized the northern leadership for not giving the southern resistance adequate time to prepare for the Tet Offensive.79 Since many of the October arrestees included military commanders who were involved in the planning for the upcoming offensive, Le Duan’s personal vendetta against Giap had finally spilled over into the war effort itself.

The final and largest round of arrests, on Christmas Day, did not involve figures associated with Giap or the moderates in the Politburo; rather, they were mainly of Party officials and Hanoi professionals who had become “suspect” under Minister Hoan’s definition, as security thugs carried out their boss’s instructions to crack down on potential leaks. Since the first arrestee, the purported Soviet spy Hoang Minh Chinh, had raised the banner for “reactionaries” to oppose the Party line with his publication, Bao Ve forces needed to round up the supposed adherents of Chinh’s “revisionist ideology” in December. The urgency, of course, was the timing of the Politburo meeting in late December and the CEC plenum in early January to pass Resolution 14 that would codify Le Duan’s GU-GO strategy for 1968. If Chinh and his associates, with “foreign” backing, leaked information regarding the upcoming offensive that relied on the element of surprise, all would be lost. By the end of the year, Party and non-Party members who had any contact with Chinh, or who had ever criticized the Party leadership after 1963, or who had any family members guilty of “bourgeois” sentiments, were summarily arrested.80

The 1967 purge thus represented the militant leadership’s conflation of ideological divisions in the internationalist movement with political repression at home so that the hawks could carry out their military policies in the South. Although leaders in Hanoi, including Le Duan, Giap, and Ho, may have adopted aspects of Chinese or Soviet policies, the ultimate goal was always to promote Vietnamese interests and ambitions. Extreme pro-Soviet or pro-Chinese inclinations may have existed among midlevel officials who had studied in either the Soviet Union or the PRC, but members of the Politburo were never that partial.81 The reasons for neutrality within the highest strata of the VWP were twofold: the Hanoi Politburo needed to steer a separate course not only for fear of alienating or displeasing one ally over the other but also to instill a sense of patriotism and Vietnamese identity within the Party and the people. However, neutrality in foreign policy did not prevent the use of ideological divisions within the international proletarian movement to control domestic politics at home. Certain leaders were not above accusing others of “revisionism” or “dogmatism” for domestic political gain.

Le Duc Tho, Truong Chinh, and Tran Quoc Hoan, who received the majority of media coverage during and after the arrests, emphasized Party control over all stages of the revolution and the need “to struggle against opportunism from left or right.”82 These leaders delivered their speeches and published their articles in an atmosphere of danger—as Red Guards and radical thinking spilled over from China’s Cultural Revolution—and of intrigue—as spy fever heightened by American bombs gripped the DRV capital.83 It is conceivable, then, that Le Duan and his faction orchestrated the arrests to capitalize on this fear by whipping up paranoia with accusations of espionage and treachery in order to ensure that the planning for the Tet Offensive unfolded in the utmost secrecy it needed to succeed. Recalling the clamor that the pro-Soviet moderates had created in the wake of Resolution 9 in 1963, Le Duan needed Resolution 14 to be passed without complications in 1968. By charging the arrestees with “sowing dissension” and “fomenting friction between Party leaders” in order to “organize a faction to oppose our Party, the Workers’ Party,” the leaders who orchestrated the arrests finally removed their long-standing opponents in one fell swoop.84 The Politburo, however, remained intact, even though some members were now fully aware of the lengths to which Le Duan would go in order to get his way. It was in this environment that Hanoi made the decision to launch what would become the major event of the Vietnam War: the Tet Offensive.

CONCLUSION

Since Hanoi was supposedly infested with spies and American bombs threatened the city, the Fourteenth Plenum took place outside the capital, in Hoa Binh province, in early January. In his opening speech, Le Duan formally elevated General Dung to the top military slot by allowing him to brief the plenum on behalf of the Central Military Party Commission. Although it would have been Giap’s duty to provide the briefing as head of the CMC, he was conveniently out of the country. As for Ho Chi Minh, the frail leader had returned to Hanoi in December to make a final stand against the GO-GU strategy at the Politburo meeting in December, but to no avail. The Politburo approved forwarding the Tet Offensive resolution to the Central Executive Committee for a rubber stamp. With the Politburo’s December blessing, then, the attendees of the Fourteenth Plenum in January 1968 reviewed and debated the risky strategy for 1968. Once again Ho abstained from the vote—just as he had for Resolution 9 in 1963—and silently watched as the revolution proceeded without him.85

Beset with problems from the start, military planners for the Tet Offensive delayed setting the date for the offensive nearly to the last minute. In order to maintain the element of surprise, war leaders in Hanoi gave local, regional, and provincial commanders in the South little more than two weeks to prepare their forces for battle. On 15 January 1968, D-Day was set for the night of 30-31 January, to coincide with Lunar New Year’s Eve. The Year of the Monkey, however, proved inauspicious for communist forces. Due to calendar discrepancies, some of the central region provinces launched their attacks one day early, thereby giving away the element of surprise, while other headquarters received their instructions too late and thus failed to “tien cong [advance].”

Without contextualizing VWP strategy deliberation within the interplay of inner Party debates and Sino-Soviet-Vietnamese relations, it is impossible to understand the full weight of the decisions made by Le Duan and his hawks in 1967. Although the military picture in South Vietnam and the political climate in the United States were important factors in the calculations of the “War Politburo,” they were not the only ones. The militants’ gamble following the 1963 Ninth Plenum to go for broke through a General Offensive and General Uprising strategy succeeded in fatally weakening the Saigon regime, but it failed to prevent the arrival of American soldiers and bombs. Le Duan, though, saw it differently. He was convinced his strategy had succeeded, but the United States had snatched away his victory at the final moment.

As near victory in 1964 turned into a costly stalemate by 1967, Le Duan and Le Duc Tho identified a solution to deflect the multiple challenges to their leadership by the “North-first” moderates in the Party who called for negotiations to end the war, by figures in the Politburo and the military who called for a more conservative military strategy for 1968, and by opinionated Soviet and Chinese allies who promoted conflicting agendas. Relying first on General Nguyen Chi Thanh, and later Lieutenant-General Van Tien Dung, Le Duan found the instruments to redeem his strategy in 1967, when the Party leadership as a whole decided that its forces needed to attempt a decisive victory in 1968. Although the General Offensive and General Uprising was a risky strategy with little chance of success, Le Duan forged ahead and cut down his detractors (foremost among them Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap) by launching the largest purge in Party history, one that remains relatively unknown. With the successful conclusion of the Revisionist Anti-Party Affair and the passage of the General Offensive and General Uprising resolution by early 1968, Le Duan could look forward to reaping the fruits of his labor in the Lunar New Year.