Chapter 2

The Fight for a Just Cuba, 1895-1898

Liberty has to be conquered with the sword, it cannot be begged for. To beg for rights is a peculiarity of cowards unable to exercise them.

— Antonio Maceo, El pensamiento vivo de Maceo

Because those of us [blacks] who as Cubans were of use in sharing the sacrifices [of the war], we as Cubans must also have a share in [its] benefits.

— Rafael Serra, La Doctrina de Martí

When Cuban insurgents launched the War for Independence on 24 February 1895,1 the rebellion succeeded fully only in Oriente, the region with a significant population of African descent and a tradition of struggle against Spain. From the insurgency’s beginning, blacks joined en masse for a variety of reasons, ranging from the need to flee Spanish repression to the possibility of improving their personal lives or contributing to the fight for a just Cuba. In the process, many of them experienced increasing expectations for better positions once independence was achieved, although, not surprisingly, racism did not vanish from social relations among rebels. More significantly, however, racism was displayed by some prominent white separatists, who did not hesitate to jeopardize the most decisive insurgent military victory over Spain in order to limit the power of black leaders from Oriente. For their part, the Spanish authorities, building on white Cubans’ century-long fear of a black takeover, immediately labeled the War for Independence a “race war” and initiated repressive policies that often targeted groups in which Afro-Cubans prevailed. Indeed, the specter of Cuba’s becoming another Haiti was still very much alive and affected not only the views that many Spanish residents and white Cubans, both on the island and in exile, held regarding the war but also the U.S. government’s position on the future of Cuba.

In fact, in order to prevent the mislabeling of the independence movement as a race war, the separatist leadership decided to divide the direction of the rebellion in Oriente right from the start between two veterans of the Ten Years’ War: the white Bartolomé Masó—a wealthy planter of Catalan origin from Manzanillo, in western and northern Oriente—and the black Guillermon Moncada—a carpenter and the natural son of a free morena from Santiago de Cuba, in southern and eastern Oriente. Among the chieftains who rose in arms that first day, in addition to Masó, some major figures were white, including Perequito Perez in Guantánamo and José Miró Argenter in Holguín. But mass support for the rebellion came mostly from the following that Afro-Cuban veteran leaders Guillermon Moncada, Quintín Banderas, Alfonso Goulet, Jesús Rabí, Amador Guerra, and others had among peasants, day laborers, and some city youth of Oriente. This following was largely Afro-Cuban, founded on family ties, labor relationships, and camaraderie in the previous struggles. As Lt. Col. Eduardo Rosell wrote in his diary shortly after he joined the rebels in March 1895, “I understand perfectly that the Spaniards say that this movement is racist, of the race of color.”2 Moreover, there was little doubt for anyone in Oriente that the real spirit of the rebellion, the uncontested leader of the people rising in arms, was Gen. Antonio Maceo, still in exile in Costa Rica.3

Until Maceo, José Martí, and Máximo Gómez landed in Oriente, however, there was little coordination in the uprising. Though united by a common will to sever ties with Spain, “each group had rebelled in its respective district, each fraction in its own way, and each cabecilla (rebel leader) at the head of his own supporters.”4 Alliances were struck with local bandits in order to ensure at least their silence, at best their integration into the independence movement.5 In reality, the rising Liberation Army was like a world turned upside down: poor, generally Afro-Cuban men of little formal education dominated the rebellion. Although few orientales were able to leave written testimony of their motivation to join the insurgency, their goal was probably not only independence from Spain but also the creation of a new society in which they would fully participate.6 Blacks rebelled against racism and inequality, landless peasants regardless of race stood up for land, popular cabecillas wanted political power, and orientales in general hoped to gain control of their region’s destiny. The potential for the war to become a social revolution was strong indeed.

After Antonio and José Maceo, Flor Crombet, Agustín Cebreco, and other exiles landed near Baracoa on 1 April 1895, the insurgency entered a new phase. The news that Maceo, the incorruptible caudillo of all past independence struggles, had arrived to lead the movement rapidly spread to the cities and countryside of Oriente. As Maceo’s small group proceeded into the interior of the province, veteran chieftains placed themselves under his command, rebel bands united with his group, and new recruits left families and bohíos to follow him, often with no arms other than old machetes and no uniforms other than rags and sandals. Country people gave what they had to help the cause, from food to their best horses. Even “whole families desert their homes and place themselves under our command,” José Maceo wrote to his wife.7 From a little over 2,000 in late March, the estimated number of insurgents in Oriente reached 5,000 one month later, 8,000 by mid-May, and 16,000 by the end of August.8 As the British consul at Santiago later reported, “Had Maceo not effected a landing, the insurrection would never have assumed its present proportions. Should anything however happen to him, it would completely disconcert the negro element, which is the powerful one here.” 9

Simultaneously, in neighboring Camagüey, the insurgency was beginning to gain ground, as Máximo Gomez proceeded into the province with a two-hundred-man escort. The social makeup of the camagüeyano rebels differed from that of the orientales, however. At the head of the small movement that took arms in June were the sixty-seven-year-old marquis of Santa Lucia—Salvador Cisneros Betancourt, a white aristocrat veteran of the Ten Years’ War—and “some young men of distinguished families” and their countrymen, who swelled Gómez’s troops.10 Although there were Afro-Cubans among the two thousand camagüeyano insurgents reported in August 1895, the predominance of whites in their ranks and of men of the “better class” in their leadership limited the revolutionary potential of the movement in Camagüey. In addition, throughout the war camagüeyanos pitted themselves against orientales at the expense of rebel unity.

In the central province of Santa Clara, insurgent bands formed around white and Afro-Cuban cabecillas in late April 1895. After the expedition of Carlos Roloff and Serafín Sánchez landed, the separatist movement gained strength in the region, totaling about 2,500 by August 1895. Santa Clara’s rebels were of very diverse social origin, with a predominance of Afro-Cubans.11 The movement in Santa Clara comprised hacendados as well as colonos (cane farmers), day laborers, and freedmen. It also included bandits, such as the Afro-Cuban “Matagás,” “Ta-Ta Monte,” and “Tuerto Matos,” who roamed the mountainous area of Trinidad.12

Matanzas rebelled only in late 1895, after an initial uprising attempt led by Juan Gualberto Gómez ended in total failure on 24 February. In this former stronghold of slavery, at least half of the insurgents were Afro-Cubans.13 In 1896, according to the black rebel Ricardo Batrell, two-thirds of the four hundred men with Col. Eduardo García were black or mulatto, and most were rural peasants—only a dozen came from towns. At the same time, the U.S. journalist Grover Flint noted that half of the seventy-man force at Sabanas Nuevas were reportedly black and two were Chinese. He estimated that in the whole province “half of the enlisted men . . . were negroes, with here and there a Chinaman,” but “a trifling percentage of negroes and mulattoes” were officers. Most chieftains were white peasants of some means, professionals, or planters, who sometimes went to the war with their own workers. In fact, the stricter social hierarchy in Matanzas (as compared with Oriente) was reflected in the organization of rebel units. In addition, regionalism was strong here, as elsewhere, and insurgents preferred to follow local leaders rather than orientales. But many rebels— especially Afro-Cuban ones—also joined the rebel movement because of Juan Gualberto Gómez’s previous leadership.14

In the provinces of Havana and Pinar del Río, where people had supported Spain rather than independence during the Ten Years’ War, the rebellion was put down right at its beginning in February 1895. It revived only in early 1896 after the troops led by Maceo and Máximo Gomez crossed the Spanish Júcaro-Morón trench and completed the invasion of the western part of the island. In Pinar del Rio, where Spanish and white Cubans were in the majority, peasants discovered with surprise that Maceo and his men were not the “head cutters” they had expected but were, instead, polite and merciful. They received them with white flags and sometimes with full support.

The inhabitants of the province of Havana, busily cultivating and trading in spite of the war, showed less hospitality at the sight of the invaders. To many of these Cubans—with the exception of separatist activists, including some wealthy young habaneros—the orientales were hardly less frightening than the late white bandit Manuel García and his men. In February 1896 Spain replaced Gen. Arsenio Martinez Campos (often referred to as the Appeaser for his drafting of the Pact of Zanjón), the governor general of Cuba, with the ruthless Gen. Valeriano Weyler, whose campaign allowed Spain to regain control of most of the region in 1897. Nevertheless, the western invasion facilitated the integration of units from the provinces of Matanzas, Havana, and Pinar del Rio into the Liberation Army.15

In general, the war against Spain brought men of completely different social backgrounds together. Blacks and whites, poor and rich joined forces to free Cuba. The Liberation Army was an integrated body in the sense that there were no distinct black or white battalions. Some claimed that it was color-blind. According to Bernabé Boza, Máximo Gómez’s chief of staff, “Here nobody cares about the color of a man, but about his talents and his self-respect.”16 The Afro-Cuban general Agustín Cebreco was more circumspect: “Here we are putting the principles of democracy into practice, because the hazards of war purify and unify, and will enrich our people who despite everything tend to the better,” he commented.17

Afro-Cubans participated en masse in the struggle against Spain. That many of them were willing to fight and die for the freedom of Cuba indicates the high hopes they placed in the revolution. Afro-Cuban mambises (fighters of the Liberation Army) cherished dreams of a better place for themselves in independent Cuba, partially based on their war experience. As one white army surgeon noted, “Of course, these deluded men imagined a state of things founded on social equality, on the supremacy of military men, of the guapos [braggarts], without the distinctions that forcibly impose themselves in any society.”18 Others were less hopeful and sensed that racism was deeply rooted in Cuban society. Among them was Col. Enrique Fournier, an educated oriental of French and African descent, who reportedly predicted to his Afro-Cuban comrades: “The race of color, which is the nerve of this war, is going to sacrifice itself so that white Cubans [can] continue to exploit their superiority [over blacks].”19

Indeed, the war offered Afro-Cubans new opportunities, on which they built expectations. Above all, there were unquestionably times of true fraternity in the army. One of these times was in November 1895, when Antonio Maceo crossed the Spanish trench at Moron with 1,700 cavalry, 700 infantry, and members of the provisional government and was welcomed by Gomez and all his forces. “We merged together, orientales, centrales, and occidentales, blacks and whites,”20 exulted Boza. Even the bitter Ricardo Batrell remembered episodes of “fraternity,” “reciprocity,” and “true democracy” between soldiers of color and white officers, especially Maj. Clemente Dantín.21 Some white leaders openly fought racism in the army. They spoke in favor of Afro-Cuban commanders when these men were discriminated against. They stood up in defense of Antonio and José Maceo when the two were accused of black racism. This was clearly the position of Lt. Col. Eduardo Rosell and Fermín Valdés Dominguez (delegate to Cuba Libre’s Constituent Assembly and vice secretary of foreign relations in 1895), who consistently sided with José Maceo and transferred racist white military men to civil posts in order to avoid problems with the troops.22 Such support from whites gave several Afro-Cubans hope of justice for the future.

On a more mundane level, Afro-Cubans had some good times in the war. A real meal with barbecued meat and starchy food, a gulp of rum, a cup of coffee, or a cigar were all sources of joy. Sometimes dances were organized with the participation of women of the region. Cockfights were held with roosters found or stolen along the way. José Maceo was reportedly one of the most enthusiastic gamblers, “and this weakness of the general brings the natural consequence that one can see in the marches the ridiculous scene of soldiers carrying along with their rifles the aforesaid little cock.”23 These moments of shared fun allowed people to imagine a simple but fraternal life when the war was over.

Afro-Cubans under the command of black cabecillas, especially Antonio Maceo, experienced (many for the first time in their lives) the pride of serving under famous leaders who were, like themselves, of African descent and lower-class origin. To them “[Antonio] Maceo was an idol,” but not an inaccessible one.24 They could identify with him and emulate him without having to question their heritage. Moreover, although hierarchy was strict, there was a climate of camaraderie in Maceo’s units that appealed to many Afro-Cubans. Most positions were awarded on the basis of courage, intelligence, and merit, and everyone felt that he had a chance to be upgraded—and downgraded, because Antonio Maceo did not keep in high positions those he called “figureheads.”25 Officers fought with their men and had all been wounded several times. In fact, during the battles, all faced the enemy in the same condition. In special circumstances, hierarchies vanished: Antonio Maceo jumped off his horse and acted like a simple soldier. “Maceo marched heading his heroic soldiers with a rifle in his hand, on foot; at his side Socarrás, as a guide, the Estado Mayor, General Bandera [sic] and others from the vanguard squadron, everybody in line.”26 Such experiences no doubt affected soldiers and made some of them believe that class and race distinctions would be banned in the new Cuba for which they were fighting.

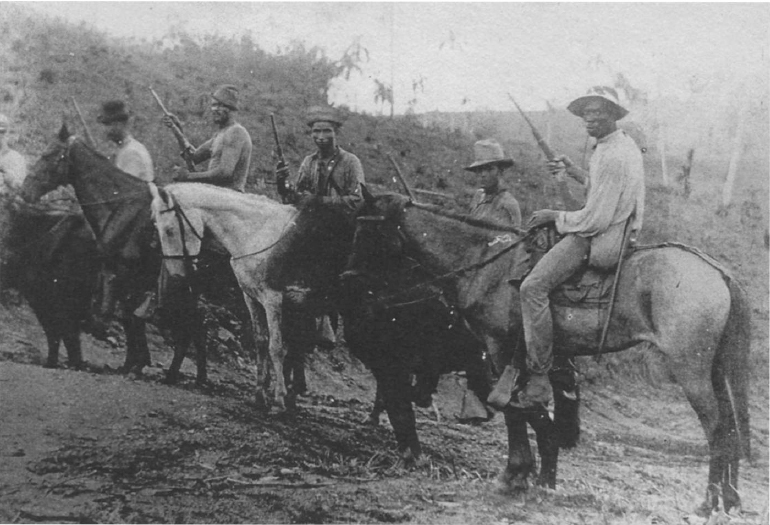

Figure 2-1.

Mambises on horseback (Biblioteca Nacional “José Martí”)

Among Afro-Cuban soldiers, the positions with the highest prestige were in the personal escort of the Maceo brothers. Several rebels risked their lives to join the divisions headed by the Maceos and to be noticed by them. The first step was often to secure a gun, and men did not hesitate to fight unarmed against Spanish soldiers in order to seize one of their Mausers. These Afro-Cubans then kept participating in battles until they acquired a reputation of bravery, strength, and intelligence. For the fifty or so men in Antonio Maceo’s escort, these efforts continued, for they all endeavored to become his chief of guard.27 Few men in the escort lived long, because they were always on the front line of the battle, with Maceo. From April 1895 to October 1896, one after the other, five of his chiefs of guard died in combat. The last one, Julio Morales, was a rough old black man with a white beard, who had been on Maceo’s side since 1868 and had finally fulfilled his life dream: “to be the chief of the escort of his intrepid and beloved caudillo.”28

The poor and little-educated Afro-Cubans who reached officer rank acquired a new self-esteem. They sensed that they were valued for their merits and talents—a concept formerly unknown to most of them. If Cuba Libre rewarded them rightfully, they doubtless thought, they would be treated similarly after independence. Some Afro-Cubans were less dedicated to the struggle against Spain, but they too had high hopes for their future. According to Esteban Montejo, many believed the war was a “fair to collect honors” but were not ready to fight; some were attracted by the prospect of pay. In fact, a number of rebels simply ignored the aims of the insurgency. “One got involved because it just happened,” Montejo recalled. “Myself I did not know much of the future. The only thing I said was ‘Cuba Libre!’”29 For their part, freedmen and African-born reportedly partook in order to eliminate Spanish domination and the kind of life that was imposed upon them: “No one wanted to see oneself in the stocks again, or eating salt meat, or cutting cane at dawn. So they went to the war,” Montejo remembered.30 Yet, although motivations were sometimes selfish, most Afro-Cuban rebels shared the sense that they were united in a struggle that would lead to better conditions for all.

In addition, to join the Liberation Army and become a soldier often meant to have a gun—the ultimate symbol of power. This partly explains why numerous rebels did not hesitate to put their lives in peril in order to grab a weapon from a Spanish soldier. They then developed a passion for that weapon. Few, in fact, would surrender their guns after the armistice, and many kept them forever, as evidence of their commitment to the republic. According to Boza, this situation was not without its problems: “Many do not know the mechanism of [their gun]. In order to understand it and also because of a kind of indescribable love for their arms that has seized almost all our soldiers, they spend whole hours handling them, aiming at anything, in sum they spend their days doing an exercise sui generis that often results in an escaped shot and an irreparable misfortune.”31

If a regiment possessed a piece of artillery, it became a treasure. Máximo Gomez entrusted Afro-Cuban captain Julian V. Sierra with an old cannon and charged him with the task of making it work. He “spent all his days studying it and inventing extraordinary and wonderful things to fix it,” until it exploded without damage, to the relief of those who had to carry and pull it.32 In another unit, the cannon needed so many men and mules to be transported that it was called “Saint Cannon.”33 Yet men cherished that cannon as if it incarnated the power they would have once they won the war.

To a certain extent even those clothed in rags and armed only with machetes, even those in the impedimenta (the group of men, women, and children accompanying the Liberation Army) chose their side in the struggle. By following the rebels, they signified that they refused to accept continuing repression under Spanish rule and wanted their condition to change. Among the men were many freedmen who were accustomed to working on sugar plantations and had little experience of the world beyond the central (central sugar mill). While most were “moved only by the hope to acquire a gun in order to take an active part in the campaign,”34 some reportedly thought that to join the Liberation Army meant “to do what one wants.”35

Figure 2-2.

Men and women accompanying the Liberation Army (Biblioteca Nacional “José Martí”)

In many respects, the war gave blacks a new pride in themselves and their African origin. Traditional Afro-Cuban skills gained some respectability in the ranks of Cuba Libre. Musicians and storytellers provided entertainment. Even before the war, most people had turned to Afro-Cuban healers for medical assistance, as scientific medicine hardly existed in rural Cuba. During the war, the services of traditional healers became all the more indispensable. The army lacked doctors, and units had their self-appointed healers, mostly charismatic Afro-Cubans who brought comfort, if not recovery, to the wounded. There were often few treatments available other than washing wounds in cold water and bandaging them with cloth, so additional aid was welcome.36 The luckiest patients were treated by local healers, who had set up rudimentary first-aid posts. Several women, in particular, became famous even among officers. One such woman was Camagüey’s La Rosa, an “independent, masterful negress, profoundly confident in her own methods,” who had a wide knowledge of medicinal plants that cured fevers, wounds, and illnesses.37 Other women managed to get to the manigua (the insurgent-held territories) to take care of their recovering husbands, sons, or nephews.38

The rank and file believed so strongly in traditional remedies that they were reluctant to see commanders resort to modern medicine. When Antonio Maceo fell seriously ill during the preparation of the western invasion, he sent for the chief of the Sanitary Division. His escort and soldiers, however, insisted that only a healer’s manipulation could save him. “If the healer is a young and nice girl, I’ll think about it,” Maceo reportedly joked. But his doctor prohibited the procedure as too dangerous. Maceo’s men then threatened to hang the doctor if their leader died.39 Moreover, wounded or sick soldiers avoided at all costs being sent to the Liberation Army hospital camps that surgeons attended. There they suffered isolation from their unit and the battle; they distrusted doctors and abhorred the camps’ discipline. Confined freedmen allegedly “protested that they had not come out of one kind of slavery . . . to enter another one.”40 In fact, sick or injured soldiers much preferred to follow the army by being carried on the shoulders of their comrades in improvised hammocks.41 In this way, some were also able to maintain the feeling that they participated in a revolution that would change their lives.

Like scientific medicine, the Catholic church had little presence in rural Cuba, especially in Oriente, where it was perceived as an instrument of Spanish domination and was resisted. People filled their religious needs in their own ways, often founding their new practices on beliefs of African origin. Charms provided by leaders of Afro-Cuban cults were popular among rebels. Fighting with few arms against a large and comparatively well-equipped Spanish army, the mambises constantly put their lives in peril. To protect himself, a mambí often wore an amulet for good luck.42 The strength of superstition in the Liberation Army surprised more than one educated white insurgent who came to discover the reality of lower-class Cuba in the manigua. In the upper strata of Cuba Libre, however, many rebels were Freemasons: Antonio and José Maceo, José Martí, Máximo Gómez, and Bartolome Masó, to name only a few. While in exile in the United States, some had been initiated as Odd-Fellows; others had joined Cuban lodges in Florida and New York. Most belonged to the Grand Orient of Cuba and the Antilles, an irregular masonry that professed independence and racial equality. Although Spain banned masonic activities in Cuba in June 1895, masonry continued to attract members in the battlefields. More lodges were created during the war, and many insurgent officers were initiated; by the war’s end the Grand Orient of Cuba and the Antilles had become an institution of more political influence than the Catholic church.43

The war provided many blacks with a new pride, not only in their traditions but also in their skin color. The Maceos became the symbols of the intelligence and strength of the raza de color, models with whom all could identify. More trivially, to be black also meant to be unobservable at night, a marvelous military artifice that made many Afro-Cuban soldiers famous throughout Cuba. Agustin Cebreco, in particular, notoriously used his own and his soldiers’ blackness, often choosing to fight at night. They disrobed from the waist up so they were almost invisible to the Spaniards but could recognize each other. Others undressed completely to steal from Spanish camps at night.44

Some old former slaves went through a sort of regeneration during the insurgency. Elder African-born men who followed their sons or nephews in the war found a new dimension to duties that they had been fulfilling as slaves. They volunteered to do essential but commonplace tasks such as washing clothes, cleaning arms, or doing night watches. They became most resourceful cooks in the scarcity of the manigua.45 As members of the impedimenta, they participated in a process that transformed them into full citizens of Cuba.

Although the war dissolved many families, a few rebels managed to maintain ties with their loved ones through messengers and new recruits who brought letters and tobacco to the manigua.46 Other men and women succeeded in creating new bonds during the insurgency. With the exception of the invading army of Antonio Maceo, most units comprised numerous female impedimenta members, who sometimes became companions of soldiers. Banderas ‘s division, for example, included Afro-Cuban women “who squatted about, doing the cooking for their husbands and their particular friends.”47 In smaller and more isolated units, this practice was more common, especially among Afro-Cubans. Several officers in Matanzas had settled their families in camps hidden in the forest near where they operated. Although they were friendly to one another, white and black families reportedly kept apart.48 There were also refugee camps of women and children in the liberated territories. When rebel troops camped out in their vicinity, people got together and men and women met.49 According to many reports, however, there was no mercy for rapists, who were always hanged, regardless of their rank.50

Although only a handful of women took part in combat, those who went with the rebels shared their lives, contributed to the maintenance of the troops, and broadened their life experience; a few probably set new goals for their future.51 Some women lived with commanding officers. It was a well-known fact that after 1897 several women lived “an immoral life” with Quintin Banderas in the mountains of Trinidad. Less publicized were the cases of women living with officers of “the better classes,” such as José María (Mayía) Rodríguez and Enrique Loynaz del Castillo.52 José Maceo also was reportedly in the war “with his women, two or three mulaticas that he calls his nieces.”53 Agripina Barroso Lazo, a fourteen-year-old oriental nicknamed La Negra, followed the general long enough to give birth to his son.54

Figure 2-3.

A military unit in Cuba Libre, comprising men, women, and children (Biblioteca Nacional “José Martí”)

The portion of Cuba under rebel control (Oriente, Camagüey, and part of Santa Clara, with the exception of the larger cities) was divided into districts and administered by prefects appointed by the provisional government. Although white prefects prevailed, there were also some Afro-Cubans, such as Florencio Grimón, a veteran of all the wars for independence, who ruled in the district of Sagua la Grande. According to Grover Flint, Oriente had schools to which parents were required to send children. Revolutionary newspapers were printed in presses hidden in the forest. Workshops, also located in inaccessible places, made use of rebels who were unfit for the army. Some men repaired arms and machetes; others made shoes, saddles, belts, and ammunition pouches; still others made clothes and straw hats.55 “The majority of those of color occupied themselves with teaching each other skills, the tailors, for example, making clothes for their comrades,” one rebel recalled.56 People in Cuba Libre also took care of concealed herds of cows, horses, and mules, as well as gardens planted with vegetables and starchy roots. Although far from a paradise, the freed territories fulfilled many basic needs of the population. On this sharing basis, Afro-Cubans, poor people, and landless peasants envisioned a better life after independence than the one they had had under Spanish rule.

In sum, participation in the war enabled many blacks, in particular, to build expectations regarding their future based on new notions of justice and equality, although patterns of relations based on a rigid social hierarchy continued to prevail in Cuba Libre. Not surprisingly, the Liberation Army did not eliminate deeply rooted race and class differences. In the Liberation Army as in most armies of the time, discipline was harsh and physical punishment was frequent. Troops were often taught with the flat of the machete, especially during marches.57 A throwback to slavery, wooden stocks served to punish disobedient soldiers.58 Military justice was merciless toward traitors, robbers, and rapists: they were always hanged, even if they were officers—in order to secure popular support and internal discipline but also in order to counter Spanish accusations that rebels were black rapists and bandits.59

Many officers, regardless of race, believed that only the fear of physical punishment secured discipline among the lower class. This was particularly true of their attitude toward the freedmen and rural workers who swelled the impedimenta, lacking military skills and a sense of the struggle for independence. Most troops stationed in the east managed to accommodate themselves to a large impedimenta, but these untrained followers were a serious burden for Antonio Maceo’s units in the west, who were continuously fighting and on the move. Maceo separated the impedimenta from his army and entrusted it to Afro-Cuban colonel Enrique Fournier, charging him with the mission of transforming about seven hundred men into a regiment. Fournier and his instructor, a Haitian with French military training, reportedly submitted their new recruits to harsh drilling. Showing no patience with these Afro-Cubans, many of whom had experienced slavery, they taught them obedience by means of machetes, sticks, and the gallows.60 The same discipline prevailed among a few African-born rebels, such as Commandant Rito Arencibia and Capt. Matías Varona, who had endured slavery and merged into the Liberation Army with their workmates, organized into infantry units.61

In addition, racial equality in the Liberation Army was hampered by the reproduction of paternalist work relations in military life. Officers had assistants, very often black or mulatto teenagers, who served simultaneously as scouts, hut-builders, food providers, cooks, messengers, and porters. Tor-cuato Camejo, who waited on José de Jesús Monteagudo, was known as “el negro de Don Chucho”; Domingo Gómez, who served the future dictator Gerardo Machado, was called “el negro de Gerardito.”62 Some whites went off to the war accompanied by their personal servants. Eduardo Rosell, who owned an ingenio in Pinar del Rio, had at his service the “negrito Alfonso,” a childhood playmate and family domestic.63 Others continued a master-servant relationship with their assistants after independence.64

Race and class differences were sustained by increasing emphasis on education rather than military performance in the appointment of new officers after 1895. This made promotion all the more difficult for Afro-Cubans and country people, who had had little access to schooling. As one white commander observed, “While those who could not read and write became only exceptionally more than simple soldiers, those who had instruction, from the moment of their entry in the Army of the Revolution, were singled out with the rank of lieutenant.”65 Medical doctors, engineers, and lawyers were assigned to nonfighting units, such as the sanitary and the judiciary corps. All of these men were white, except for a handful of Afro-Cubans, such as Martin Morua, who joined the rebellion only in June 1898 to become “lieutenant without having held the machete . . . and spent his life in the camp’s archives.”66 The few illiterates who gained promotion did so either because of their outstanding contribution to the war or because their example boosted the morale of the troops.67

Such a man was Quintín Banderas. Born a free black in 1834, Banderas was a mason in El Cobre (Oriente) when he left his family in December 1868 to join the rebels in the Ten Years’ War. Like many Afro-Cuban orientales, his aim had been not only to free Cuba from Spain but also to free blacks from slavery. In 1878, Lieutenant Colonel Banderas had been among those who rejected the Pact of Zanjón and launched the Guerra Chiquita. In 1880, he and his companions had been arrested by Polavieja and deported to a Spanish penitentiary off the coast of Africa for six years. When he returned to Cuba, he had resumed underground revolutionary activities. Arrested again in 1893, he was imprisoned for eight months in Santiago de Cuba. At the outbreak of the war in 1895, Banderas was in command of the thousand-man infantry of mostly Afro-Cuban orientales who undertook the invasion of the west with Maceo. He spent the second part of the war in the region of Trinidad charged with the task of diverting the Spanish army’s attention through sabotage and fighting.68 On the basis of his military achievements and an entire life dedicated to Cuba’s independence, Banderas was promoted to division general.

The case of Banderas was unique. Foreign journalists noted the racial imbalance between troops, among whom Afro-Cubans were overrepresented, and officers, among whom whites predominated.69 Most Afro-Cuban mambises received few rewards for their courage. Thus, the automatic promotion of men with some education concerned them. For example, “Chigüí,” a mulatto scout and servant of a white officer, reportedly complained to his superior that he always had to take risks and walk point on reconnaissance missions, while “for the city dandies it was enough to join the war in order to immediately become colonel and lieutenant colonel.”70 Batrell also claimed that due to “the antagonism and antidemocratic spirit” that reigned, Afro-Cubans who performed heroic acts were not promoted accordingly. Black officers were demoted or sentenced to death on allegations of indiscipline, but the real reason for their punishment, he charged, lay in their skin color.71

Regardless of the number of stripes they wore, Afro-Cuban generals and officers faced racism in their relations with civilians throughout the war. Banderas, for example, was refused a dance in Holguín by a young white woman solely because he was black. Only the tactful intervention of Antonio Maceo prevented him from creating a public disturbance. Such incidents were not isolated and showed that prejudice still ran high in some sectors of Cuba Libre society.72 Afro-Cuban officers with strong leadership were ridiculed or distrusted for allegedly being arrogant, ambitious, and racist. This was especially true of Antonio and José Maceo, against whom accusations of dictatorial or racist ambitions multiplied in proportion to their military successes.73 Banderas too was often accused of “fighting for the blacks.”74

Conversely, other Afro-Cuban leaders were praised for their modesty. This was the case with Gens. Jesús Rabí and Pedro Diaz Molina. Rabí, the chief of one of two divisions in Oriente in 1896, was reputed to be highly professional, nonauthoritarian, and kind to his men.75 Diaz became the head of the army in Pinar del Rio in 1897, after the death of Antonio Maceo and the capture of his successor Juan Rius Rivera by the Spanish. An Afro-Cuban from Santa Clara and a veteran of the two previous wars for independence, Díaz returned from exile in New York in the early 1890s to be a sugar workers’ contractor and a colono near Remedios; he joined the insurrection with a small group of rebels recruited in his area. A competent general, he was held up by whites as an example of the “good black” who did not seek prestige and popularity.76

Accusations of black racism forced Antonio and José Maceo to appoint whites to positions of command in the territories under their control. José Miró Argenter, Antonio Maceo’s chief of staff, recalled that when Maceo completed the western invasion with overwhelmingly black troops in early 1896, he chose to appoint the white Rius Rivera rather than Pedro Diaz as commander of Pinar del Rio in order “to silence the venomous tongues and to undo the prejudices, suspicions, mistrusts, and false slanders of the Caucasian group.”77 When Lino D’Ou and two other Afro-Cuban members of José Maceo’s staff asked him to add a fourth black officer who had a broad cultural background and had mastered English, Maceo refused on the basis that it would increase accusations of racism against him. “You obviously do not know what life and the war are like,” José Maceo reportedly told his Afro-Cuban officers. “I know the value of [the candidate], but here, on my side, I do not want anymore of color than those who are now. You should know the war from the inside.”78

Afro-Cuban officers who headed mostly black troops also confronted discrimination. Although the existence of almost all-black units was the natural product of the Liberation Army’s mode of recruitment, in which local cabecillas raised troops among parents, dependents, friends, and neighbors, it nevertheless caused concern among the white leadership. According to Batrell, his unit in Matanzas was entirely of color and was led by an officer of color. “This made a bad impression, given the antagonism that still existed among the revolution camp where it was not without some prejudice,” he commented. But the attempt to replace their colonel with a white one failed, presumably because the latter could not bear continuous skirmishes with Spaniards. Batrell’s unit often faced hatred from others and received fewer arms and less ammunition simply because it was composed of Afro-Cubans, he complained.79 The former slave Esteban Montejo also mentioned the “hatred for blacks” during the war, which once led some to accuse Banderas of attempting to surrender to Spain. He recalled another instance in which he and others killed their white chief, the bandit Cayito Alvarez, because of his violence and his dealings with the Spanish. Some then circulated the rumor that Montejo and his comrades were motivated by their black racism.80

Thus, predictably enough, the Liberation Army did not fully eliminate the double standard that ruled the lives of whites and blacks in colonial Cuba. Afro-Cubans needed to accomplish more than whites to be rewarded. White commanders were praised for their ambition and popularity, but black commanders with the same qualities were called racist and dictatorial. Afro-Cuban leaders were under special white scrutiny that reinforced continuing prejudice and fear of a black takeover along Haitian lines. Yet continuing racism coexisted with limited Afro-Cuban upward mobility in the Liberation Army. This contradiction indicated a real potential for thorough social change, and on this notion many Afro-Cubans built hope of a fair share in the future Cuban republic. But, simultaneously, blacks’ limited mobility also helped to sustain the myth that racial equality had been achieved in the Cuban military forces which fought against Spain and that, as a result, racism had been defeated forever in Cuba.

In reality, however, some white Cubans used racism as a means of limiting the revolutionary potential of the movement for independence. Especially active among them were some nonfighting sectors of Cuba Libre, united around the president of the provisional government—Salvador Cisneros Betancourt, marquis of Santa Lucia—and the all-white leadership of the separatists in the United States. At stake was the nature of the new Cuban society. Schematically, on one side the rebels and their military commanders fought for the destruction of the colonial order, with its strict racial and social hierarchy. When they burned the countryside, they targeted the epitome of colonial exploitation: the sugar industry. They waged a war without concessions, aiming for Spain’s full defeat. On the other side, both the provisional government and the separatists in the United States had a more political agenda: the end of Spanish rule without a complete reversal of the socioeconomic order.81 The struggle between these two visions of society expressed itself primarily in rivalries between the civil and the military powers.

Contradictions within Cuba Libre were already visible in the contrast between the lifestyle of the Liberation Army and that of the provisional government. Little discipline existed in Cisneros’s encampment. “There were a number of lusty young aides with the Government, occupying positions one would expect to find filled only by rheumatic veterans,” Flint reported.82 Valdés Domínguez, too, had few kind words for “this cave full of vipers” consisting of young, vain men who spent their time criticizing friends and comrades and had no respect for “the old soldier” or “the good patriot who has sacrificed everything in the name of honor.”83

In fact, the question of the civil versus the military dated back to the meeting of Maceo, Máximo Gomez, and Marti at La Mejorana, near Santiago de Cuba, in early May 1895. Maceo, looking back at his past experience, insisted that the failure of the Ten Years’ War and the Pact of Zanjón was due to the supremacy of the civil power; he argued that the insurgents needed a strong military junta until they won independence from Spain. Marti, on the contrary, looked at the future of independent Cuba and sought ways to avoid the establishment of a military dictatorship; with the support of Gomez, he argued in favor of civil control over the military and the election of a civil government during the war.84 The three leaders had been unable to reach an agreement.

After Martí’s death in a skirmish near Bayamo in mid-May 1895, Maceo’s military successes and wide popularity in Oriente began to raise suspicion among other leaders that he planned to promote himself as a dictator. Personal jealousies also developed against him and his brother José, because “it is undeniable that [the troops] adore the Maceos.”85 Especially opposed to them was Bartolomé Masó, chief of northwestern Oriente, who took increasing offense at his rivals’ influence in the army and over the oriental population.86

Open confrontation between the separatist leaders erupted in September 1895 at the meeting of the delegates to the Constituent Assembly, in Jimaguayú. The issue of civil versus military predominance resurfaced. Moreover, before the meeting Masó, Cisneros, and others renewed accusations that Antonio Maceo had ambitions to become the military and political dictator of the revolution. They claimed that Maceo had advanced himself to chief of the army in Oriente (a function he had already assumed in 1878 after most separatist generals had subscribed to the Pact of Zanjón). Although a majority of delegates for Oriente were white and acted independently of Maceo, Masó and Cisneros accused them of serving the racist and regionalist interests of the Afro-Cuban leader. Cisneros also charged Maceo with illegally publishing El Cubano Libre as the official mouthpiece of the Oriente insurgents and with using the newspaper to promote his dictatorial ambitions. He tried to lure Maceo into accepting a merely symbolic position in the revolutionary government.87

Clearly, the onslaught against Antonio Maceo was not only a personal feud but also one with a social and racial basis. Coming from such men as Cisneros and Masó—who could claim nobility, “pure” Spanish origin, wealth, and land—it aimed at asserting that part of the old order would be maintained after independence, with Afro-Cubans and whites of popular origin being excluded from power. By attacking Maceo, Cisneros and Masó targeted all who had rebelled against Spain in order to build up a society in which poor and blacks would have their rightful share. The onslaught also had a regional significance. It showed that although they were less numerous and slower to rise in arms, the insurgents of the whiter areas like Camagüey and northwest Oriente refused to let the revolution be led by predominantly black southern orientales.

Maceo’s response to the attacks by Cisneros was unequivocal. He had never sought favors, but only positions based on his own merits, he disdainfully wrote to the marquis. Moreover, he knew that his darker skin and humble origins would not be overlooked in the light of his achievements: “From the beginning the humbleness of my birth prevented me from placing myself at the level of others who were born [with the right] to be leaders of the revolution. Perhaps this explains why you feel entitled to suppose that I will be flattered by what you say will be my share in the [power] distribution.”88

The provisional government installed by the Constituent Assembly of Jimaguayú further showed that prejudice had not disappeared from Cuba Libre. Cisneros was elected president of the republic, Masó vice president. Tomás Estrada Palma became delegate plenipotentiary and foreign representative in the United States. The four secretaries—Carlos Roloff of war, Rafael Portuondo of foreign relations, Severo Pina of treasury, and Santiago García Cañizares of the interior—were also white, as were all the vice secretaries. Only three out of eleven were from south Oriente.89 According to Valdés Domínguez, then vice secretary of foreign relations, “the marquis [Cisneros] represented Camagüey, Pina, Sancti-Spiritus, and Masó represented Bartolomé Masó and his grudge against the Maceo brothers.”90 The Dominican Máximo Gómez was elected general in chief of the army. The position of lieutenant general, or second in command, was created for Antonio Maceo, because it was allegedly inappropriate to have a man of color in a higher position “because of the judgment of those abroad,” and because Maceo feared new accusations of dictatorial ambitions.91

The provisional government reorganized the army in order to keep Maceo and the southern orientales in check. The province of Oriente continued to be divided into two military corps, one under Maceo (replacing Guillermón Moncada, who died in April 1895), the other still under Masó. There were three additional divisions—Camagüey, Santa Clara, and Matanzas— under the command, respectively, of Mayía Rodríguez, Roloff, and Manuel Suárez, all of whom were white.92 The civilians hastily demanded allegiance from the military. Chieftains and officers had to incorporate their forces into the restructured Liberation Army within two months. All new promotions in the five army corps had to be approved by the government.

New rules ensured preferential positions to men with education. In fall of 1895 the provisional government decided that students joining the insurgency would automatically be promoted above soldiers. Two years of secondary schooling in a colegio led to an appointment as corporal, the title of bachillerato (secondary school diploma) to second lieutenant, and a university title to at least captain. Higher rank also meant higher pay after independence: 30 pesos per month for a soldier, 40 for a corporal, 130 for a captain, and up to 500 for a general.93 As education was an area in which discrimination against Afro-Cubans was especially strong, the measure favored urban whites. Such “privilege” annoyed Antonio Maceo, who worried that “the preference granted to some while others with less instruction but more merits and military talents to ascend in the career are disregarded” would cause “general discontent.” He recommended that Gomez follow the new rules “with discretion” in order to respect the “acquired rights” of the majority in the Liberation Army.94 Although bravery and military achievements were still rewarded with promotion in combat units, the new demand for education intensified the whitening process of Cuba Libre’s officer corps— a process that had already begun due to the death of most of Maceo’s Afro-Cuban lieutenants and their replacement with whites during the first months of the war.95

It was in this difficult context of social change in the officer corps and tensions with the civil power that Antonio Maceo undertook the most successful campaign of the war: the invasion of western Cuba. About 1,700 men left Baraguá in Oriente on 22 October 1895. Most were cavalrymen, followed by infantrymen led by Quintín Banderas. Exactly three months later, on 22 January 1896, they reached Mantua in Pinar del Rio, at the other end of the island. Simultaneously, the forces under Gómez, which accompanied Maceo’s column from Santa Clara to Havana, had established a stronghold in the province of Havana.96 The western invasion represented a double victory. First, it was a military success. Although Maceo and his troops dramatically lacked arms and ammunition and proceeded into regions (mostly in open country) they knew little about, they won over Spanish forces that were well armed and ten times more numerous. Second, it was a political achievement. The invading column carried the revolution to a portion of the island where support for Spain was strong. At the same time, it broke the localism of orientales who had not envisioned their struggle beyond the limit of their home area. Many had been unwilling to march to the west. As the invading column left Oriente, desertions of cabecillas and others multiplied until severe repression had to be implemented. As a result, in January 1896 the independence struggle had acquired a truly national dimension.97

Instead of rejoicing at such success, however, the provisional government saw in the western invasion a threat to their political aims and further evidence of Antonio Maceo’s supposed dictatorial plan. In a letter to Estrada Palma, Cisneros expressed his distrust of the general “who considers himself as the unique chief, not only of Oriente but perhaps of all Cuba. Oh human miseries and ambitions!”98 He thus attempted to limit the impact of the invasion by various means. To begin with, the provisional government hampered the actions of the military by getting increasingly involved in army affairs, to the great dissatisfaction of Maceo and Máximo Gómez. The civilians opposed or imposed new officers, appointments, and strategies. Though the two generals were fighting the bulk of the Spanish troops in western and central Cuba, the politicians turned a deaf ear to their demands for arms and reinforcements. They ignored Maceo’s conviction that, with supplies and fresh troops from the east, the Liberation Army could soon beat the Spaniards. On the contrary, Cisneros repeatedly countered the general in chief’s orders for eastern reinforcements and kept men and arms in Oriente and Camagüey. In particular, the government commanded Mayia Rodriguez to remain in Camagüey, despite the fact that Maceo was desperately counting on his support in the west. It justified this decision with obscure reasons of “high politics” that aimed, in fact, at limiting the power of the military and keeping Maceo’s troops isolated in Pinar del Río.99 As a result, it jeopardized the most decisive insurgent victory over Spain. As Maceo bitterly noted, “with the Council of Government . . . will rest, before history, the responsibility for this event that has prevented us from directing our triumphs to a Cuban Ayacucho.”100

Simultaneously, the provisional government encouraged regionalism and racism within the independence movement. Cisneros made no secret of his racist and classist views. To Flint, who asked him if he feared a race war after independence, Cisneros answered, “Our negroes are far superior to the colored race of the United States. They are naturally peaceful and orderly, and they desire to be white, like the whites.”101

Cisneros attempted to remove other prestigious Afro-Cuban field officers from positions of command. Since December 1895, he had plotted to depose the recently appointed division generals in Oriente, José Maceo and Jesús Rabí, because “these chiefs were not the legitimate ones for such high positions.” He urged Estrada Palma to recall from exile Calixto Garcia and other white veteran officers “of good condition” to replace them.102 In March 1896, leaders from Camagüey renewed attacks against orientales, especially Antonio and José Maceo, for allegedly being black racists. Cisneros repeated such denigrations and hinted that the Maceo brothers planned to control the revolution, with Antonio in the west and José in the east. “It is necessary to cut this evil from the root with an astute and expert hand, to cut this evil in its origin and to cut it from its root. . . . [H]ere [in Oriente] Valdés Domínguez united to [José] Maceo and two or three others could form their schism, but I hope to cut it at its source,” Cisneros wrote to a friend.103

On the pretext of bringing order to Oriente, Cisneros bypassed Máximo Gómez’s authority in the spring of 1896 and continuously sought to depose José Maceo from the command of Oriente. He eventually managed to install Calixto García in the position, although the latter had just joined the rebellion from exile (almost a year after the Maceos) and had few men behind him. In June, José Maceo resigned, claiming that for him “it was a question of dignity . . . not to accept any of these generals as [his] superiors, because they did not have the merits justifying the position.” 104 Calixto Garcia further humiliated him by refusing to allot new guns and ammunition to his already poorly armed unit.105 In this very tense atmosphere, on 5 July 1896 a disillusioned José Maceo died in combat against Spanish soldiers. Understandably, the rumor spread among his troops that he had been assassinated by García’s men.106 The death of José Maceo did not satisfy García, however. Because the soldiers had not, as he had expected, accepted him as the new undisputed leader of Oriente, he accused all oriental forces of black racism and charged José Maceo’s lieutenants with corruption, apparently in order to disarm the southeastern troops in favor of his contingency in Holguín. As one officer opined, García’s “hatred for the Maceos led him to hate all men of their race.” The officer feared that such an attitude could jeopardize not only García’s leadership in Oriente but also the revolution as a whole.107

For their part, Cuban representatives in the United States did not view the western invasion and the destruction of the sugar industry favorably. They increasingly tried to halt a process that was, in their eyes, all too revolutionary. Estrada Palma showed clear signs of being more interested in U.S. recognition of the Cuban belligerency than in providing the rebels in Cuba with arms and ammunition. He played down the participation of blacks in the insurgency and used the whitening of the leadership of Cuba Libre as an argument in favor of U.S. recognition. He neglected to send armaments to the invading army in the west, although Maceo had asked for “30,000 rifles and 1,000,000 shots” from abroad and reinforcement from the east “to finish up the war.” 108

Discontent among military leaders against Estrada Palma increased. Some began to suspect that he favored U.S. annexation of Cuba.109 Maceo, in particular, opposed the delegate’s insistence on obtaining U.S. recognition of the insurgency. He reacted angrily to the fact that arms and ammunition were sent not to his forces in the west but to Oriente and Camagüey, where—with the exception of Jesús Rabí, José Maceo, and Agustín Cebreco—commanding officers did little to distract the Spanish general Valeriano Weyler from his offensive against the invading army. Only in September 1896 did an expedition, led by Rius Rivera, finally bring arms to Maceo’s units.110

By November 1896, distrust between the military and the civil powers had reached a climax. Máximo Gómez planned a coup to oust Cisneros as president of the government. He ordered Maceo to cross the western trench guarded by the Spanish and to back him in Santa Clara. As a result, Antonio Maceo was killed near Havana on 7 December 1896.111

Antonio Maceo’s death was devastating to the morale of the Liberation Army. “Sadness was in everyone, but even more pronounced, naturally, in the people of color,” noted Rosell in his diary.112 Another mambí recalled that he had never witnessed such deep sorrow in strong men used to danger and death. When the news reached Gómez’s camp, “the entire staff. . . hats in their hands, silent and their eyes fixed on [the general in chief] seemed possessed by a religious emotion.” Even the tough Gomez cried.113 Conversely, the news was received with joy in Madrid and in the Spanish ranks. The general feeling was that Maceo was a man of unique talents and popularity in Cuba, equaled by no other rebel leader. With his death, Spaniards thought, Afro-Cubans would lose their readiness to fight, and white Cubans would predominate in the insurgency, opening the way for conciliation.114

The killing of Maceo no doubt marked a turning point in the war. For many, especially among Afro-Cubans, Maceo embodied the revolution itself: continuous struggle until the victory and refusal to compromise, combined with humanitarianism. He had acquired a supranatural prestige among the rank and file for the numerous life-threatening wounds that he had survived. He had also become the standard-bearer of Afro-Cuban hopes for full participation after independence. His death made every soldier feel more vulnerable and every Afro-Cuban less secure of a better future. The shock was so great that the Liberation Army was paralyzed for several days.115 Some separatists in the manigua and in exile were so incredulous that they believed Maceo had been betrayed and assassinated by Weyler’s men.116 Because his comrades had buried Maceo’s body secretly to avoid Spanish desecration, others thought that he was still alive and was once again recovering from his wounds.117

The loss of Maceo gave a free hand to the civil faction and the delegates in the United States. Máximo Gómez could not face them alone and developed doubts about the meaning of his struggle for the Cubans. Many of his generals had lost stamina and entered a dissolute life.118 One year after Maceo’s death, Cebreco wrote expressively from the fields of the revolution to two separatists in exile: “To mourn for [Maceo’s] death, I am the only one still alive. My heart is with yours to feel our homeland’s sufferings.” 119 Meanwhile, Weyler progressively reconquered most of the western provinces, but he appeared unable to restore peace on the island despite systematic repression. Most of Santa Clara, Camagüey, and Oriente remained under separatist control. The Liberation Army, poorly armed and facing a Spanish army several times its size, could not achieve any major military breakthrough and focused mostly on destroying sugar plantations. Powerful sectors of the Partido Revolucionario Cubano, rather than encouraging the war, increasingly sought a negotiated solution that involved the participation of the United States.120

The civil branch of Cuba Libre continued to show its attachment to colonial hierarchies. The new assembly of representatives elected in October 1897 had not a single Afro-Cuban member; instead it comprised “men of refinement,” many of whom were graduates from U.S. colleges. The new provisional government was all white as well, with Bartolomé Masó replacing Cisneros as president. Máximo Gómez was reelected general in chief. Antonio Maceo’s position, that of lieutenant general, went to Calixto Garcia.121 Tomás Estrada Palma remained delegate plenipotentiary in the United States and secretly maneuvered for U.S. annexation.122 He urged the insurgents not to burn the properties of U.S. and proindependence planters. He also assured the U.S. government that should it intervene in the war, it could count on the collaboration and obedience of the Liberation Army. In March 1898, the provisional government confirmed such assurance.123

Like the marquis of Santa Lucia one year earlier, Masó portrayed Afro-Cubans as obedient and faithful to whites. He had no progressive views on the destiny of blacks in independent Cuba.

Our negroes . . . are mostly uneducated laborers, quite unfitted [sic] for holding positions. They will have the citizen rights, as given in the United States, and with sufficient employment will give no trouble. The population of Cuba is composed of one-third colored, either mulatto or negro. Yet some gravely predict Cuba’s future as a second Hayti [sic] or Liberia—a negro republic. This idea is manifestly absurd. Cuba is much under-populated, and one of our first measures will be to induce a restricted immigration of those likely to assist in developing our immense resources. Our negroes will work as before in the cane-fields, and I see no reason to anticipate trouble from them. We have no colored officials in this government, and very few of our officers are black, though the slaves we freed by the last war are fighting faithfully in this.124

Masó did not sense that many Afro-Cubans had joined the revolution in order to ensure a better future for themselves. In fact, he envisioned them only as sugar workers, as in slavery. In addition, he announced one of the most important policies designed by Cuba’s first independent government in order to reduce the proportion of blacks in the island’s population: subsidized white immigration. Because the position of Presidents Cisneros and Masó on the “black problem” paralleled their attitude toward the Maceos, it cannot be attributed to a need to reassure a foreign audience. In reality, it indicated that prejudice still ran high in some white separatist sectors that opposed social revolution.

If the black presence in the troops and leadership of the Liberation Army posed problems to some white separatist leaders, a fortiori it also worried many white Cubans not committed to the cause of independence. This was a fact that the Spanish authorities knew well: since the Haitian Revolution, more than a century before, they had played on white Cubans’ fear of blacks to cause divisiveness among them. Not surprisingly, thus, when Cuban insurgents launched the War for Independence in Oriente on 24 February 1895, the Spanish government immediately revived the specter of a race war: Although it coincided with a transfer of power from a Liberal to a Conservative administration in Madrid, the uprising was interpreted in similar ways by the two parties. Spain’s newly appointed Conservative prime minister, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, declared to the New York Herald that “the majority of the insurgents are mulattoes and foreigners” followed by men left without work after the zafra. The outgoing minister for overseas territories described the rebels as “a lot of desperate people . . . mainly . . . negroes. . . . I call this merely a race war,” he concluded.125 Spanish politicians added that, while the Ten Years’ War had been led by Cuba’s white landed aristocracy, this new rebellion was a “barbarian” upsurge of “uncivilized” lower-class people.

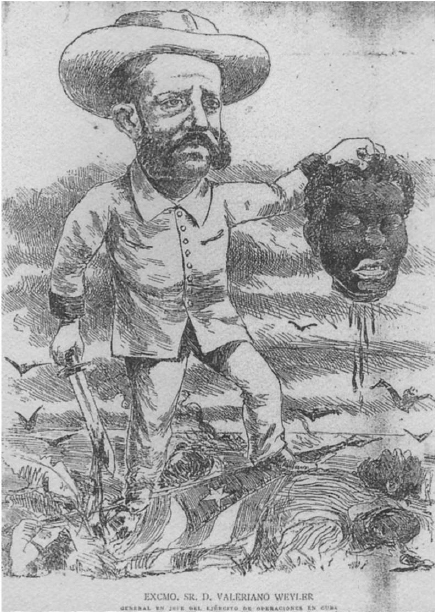

Figure 2-4.

His Excellency Mr. Don Valeriano Weyler, standing on the flag of the defeated Cuba and brandishing the cut-off head of an Afro-Cuban man. The drawing appeared in a Madrid newspaper, in February 1896. (Public Record Office, London, FO 72/2024)

Until 1897, Spanish propaganda hammered out the same message: the rebels were not representative of true Cubans because they were mostly blacks and foreigners. The death of José Martí, the educated son of two Spanish immigrants, in May 1895 only reinforced their argument. To illustrate their thesis, Spanish officials pointed out the Liberation Army’s numerous Afro-Cuban leaders, especially Antonio Maceo, and its commander in chief—Máximo Gómez, a native of Santo Domingo.126 Against this backdrop, Cánovas easily brandished the scare tactic of another Haiti. “The fact that this insurrection threatens Cuba with all the evils of Haiti and Santo Domingo, and with the triumph of the coloured people and perpetual wars of races, virtually obliges the whites in Cuba to side with Spain.”127

During this same period, books and newspaper articles that carried a similar message were published in Spain. As soon as colonial ties with Spain were cut off, polemicists claimed, blacks would resume the fighting and launch a race war against Cuban whites.128 Another argument that fared well was that the United States, not willing to allow a black independent state near their Atlantic coast, would annex Cuba and (to make up for the failed project of black voluntary emigration to Liberia) would deport to the island the U.S. citizens of African descent.129

In Cuba, the Spanish conservative Diario de la Marina led the press campaign portraying the insurgency as “black and barbarian.” The newspaper claimed that without Spain, Cuba would be nothing but “desolation, ruin, death, and racial hatreds with their horrible following of savageness and ferocity.”130 It wrote that almost all the insurgents in Oriente were poor and of color, men “transformed overnight from simple day laborers into chieftains with power of life and death.”131 It reported the complete thwarting of the uprising in Matanzas in early 1895, with full details about the death of the famous bandit Manuel Garcia on 24 February and the arrest of Juan Gualberto Gomez on 2 March. On this basis, it characterized the independence movement as criminal and racist.132

The Diario de la Marina attempted to discourage white Cubans from joining the insurgency by alleging that the rebels pursued the establishment of a black dictatorship. Their strategy was presumably to eliminate the Spaniards first in order to turn against white Cubans later. Afro-Cuban commanders were said to refuse to enlist whites in their troops. Allegedly, during May and June 1895, white rebels, victims of the cruel dictatorship of Antonio Maceo and of the racial hatred of their black comrades, continued to surrender to the Spanish authorities.133 Oriental Perequito Pérez, “one of the few white rebel chieftains,” was rumored to have been excluded from all positions of power by Maceo and to have been dragged by a rope by the insurgents.134 As for Gen. Bartolomé Masó, he supposedly had been “materially kidnapped” by black cabecillas who did not let him exercise command.135

As the Liberation Army advanced westward destroying plantations and communication networks, the pro-Spain Cuban press increasingly diffused images of hordes of fierce black men and adventurers burning fields and farms, pillaging the countryside, murdering white men and children, and raping white women.136 Pro-Spanish guerrilleros often referred to Afro-Cuban insurgents as ñáñigos, an indication that they perceived them as criminals empowered with secret African magic rather than as separatists.137 According to the most fearful fantasy, Quintin Banderas was pillaging the countryside with his bands of seminaked black men adorned with gold nose rings.138

By using traditional icons of fear drawn from racial and sexual stereotypes of blacks, Spanish propaganda transformed rebels into collective and personal threats to the white population. As might be expected, the mislabeling of the independence struggle as a race war was quite successful. Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz recalled that his grandfather, a Spanish military man, always identified a mambí as a black or a mulatto and referred to Martí as an “inward mulatto.”139 Many Cuban-born whites, especially among the Autonomists, shared such ideas.140 Autonomist congressman Rafael Montoro, in particular, closely followed the officiai Spanish line of interpretation of the war:

I speak as a Cuban, and as a Cuban I maintain that the present rebellion in the eastern department is a mistake and cannot triumph. It is principally a revolt of the blacks. In New York and elsewhere there are intelligent Cubans who are fierce nationalists . . . from a distance. But who are the chieftains of the revolt? The two Maceos, black in their blood and in their affinities; Gómez, a foreigner suspected of following selfish interests in Cuba; Massó [sic], the only white Cuban of some importance, a malcontent; Rabí, Goulet, Miró [sic] and many others, all men of color.141

In early March 1895, leaders of the Autonomist party sent a delegation to convince Masó to withdraw from the movement—an attempt that failed but was partly aimed at depriving the Liberation Army of its best-known white general in order to stop white enlistment. On 4 April, Autonomist leaders issued a manifesto in which they condemned the armed struggle and warned the “people of Cuba” against the risk of “barbarism” and “regression on the path to civilization” inherent in the uprising.142 Attributing all recent reforms conceded by Spain to their own activism, they presented full autonomy as the only solution for Cuba.

As the country settled into a state of war, Autonomists confronted head-on the question of the large participation of Afro-Cubans in the insurgency. The most representative response was a study by Eliseo Giberga, which attributed the phenomenon mainly to the de facto exclusion of the population of color from politics and socioeconomic advancement after the Ten Years’ War. Yet Giberga condemned the immoderate ambition of mulattoes and orientales of color. According to him, Afro-Cuban support for independence represented a major threat to the future of Cuba. It had “pernicious racist leanings” and could easily lead to the formation of a distinct political party by the population of color.143 In order to avert a disaster, Giberga demanded immediate self-government and universal male suffrage for Cuba. Only full Afro-Cuban participation in existing political parties and economic reform would stop the movement for independence, he concluded. But until 1898 Giberga’s demands went unnoticed in Madrid.

Spain’s labeling of the separatist insurrection as a black racist uprising seriously affected the daily lives of Afro-Cubans in the Spanish-controlled territories. Blacks were generally considered pacíficos (i.e., potential, if not actual, agents of the revolution) and were placed under special scrutiny. In the provinces of Santa Clara and Matanzas, where the poor rural population included many Afro-Cubans, rumors of bands of armed blacks frequently circulated. There were unconfirmed reports of rapes of white women by Afro-Cuban insurgents. In some cases, black rural workers were mistaken for rebels.144 Everywhere, Afro-Cubans found themselves under pressure. According to the Cuban historian Pedro Deschamps Chapeaux, the renewal of Spanish persecution of blacks motivated a significant number of Lucumis to return to Africa from Havana in 1897.145

Repression against insurgents, especially Afro-Cuban ones, was swift. Alleged rebels caught with arms were often summarily executed. Unarmed rebels were deported to penitentiaries in Spain and Africa. Contrary to Polavieja’s policy in 1890, however, race was not taken into account in the selection of the penitentiary to which political prisoners were banished. The hacendado Manuel Rigueira, Juan Gualberto Gómez, the lawyers José Antonio González Lanuza and Alfredo Zayas, the young Afro-Cuban rebel Generoso Campos Marquetti, and both black and white laborers were all sent to Ceuta in North Africa. Treatment depended mainly on class, though: those with wealth or fame were exempted from forced labor and could rent out decent places to live; the others had to work and sleep with common criminals until Gómez, through his connections in Madrid, managed to obtain general improvement of the conditions of Cuban political deportees.146 Fever, disease, insufficient food, and maltreatment nevertheless decimated them. According to one inmate, of the 119 Cuban deportees in Fernando Poo in 1897, 41 died in the course of that year.147

The revival of icons of fear used to stereotype blacks was echoed in policies used to repress specific groups in which Afro-Cubans prevailed. Under Weyler, city authorities were given a free hand to persecute people living on the fringes of the law, notably ñáñigos and homosexuals. Alleged ñáñigos were deported to penitentiaries without trial but with recommendations for harsh treatment. In August 1896, the killing of a notorious ñáñigo in a settling of scores between juegos caused the roundup of 92 suspects, of which 30 were later released and all the others deported. During November 1896, 104 alleged ñáñigos were arrested in Havana alone, and 74 of them were selected for deportation after review by the chief of police. In many cases, a tattooed letter or sign on the chest or the arm, together with visible African features, served as evidence; other suspects were recidivist criminals.148 More than 580 supposed ñáñigos were deported during the war; most of them were black or mulatto, while about one-quarter were white.149 Until the end of September 1896, they were assigned to the penitentiary of Fernando Póo, an island situated, ironically, just off the estuary of the Cross River on the Niger Delta, where the Abakuá society had its origins. Later they were deemed too immoral to contribute positively to the colonization of the island and were imprisoned elsewhere. The death rate among them was as high as 20 percent due to disease, epidemic, abuse, and lack of food and medical care.150 At the time of their release, their physical condition had deteriorated to the extent that “they need to be dressed because they are not presentable.”151

Simultaneously, in 1896, a large number homosexual men, the majority of whom were reportedly mulatto, were arrested in Havana, and dozens were deported to the Island of Pines for the duration of the war.152 Interestingly enough, no black brujo appears in the lists of deportees. If brujería had been considered a threat to social order in 1896-97, Weyler would not have lost the opportunity to repress this mostly Afro-Cuban group, but black brujos or those alleged to be were not the focus of any particular campaign during the war.153

Accusations of racism against Afro-Cuban insurgents and repression of blacks led some sociedades de color loyal to Spain to protest the rebellion “in the name of their race” and to announce that they sided with Spain. The only outstanding Afro-Cuban still affiliated with the Autonomist party, Martin Morua, dedicated some effort to disproving that the rebellion was racist. In June 1895, he claimed that among the chieftains of Oriente, twelve were white and only nine were black or mulatto; more important, all the leading revolutionary positions except three were in white hands; and, finally, Morua argued, in Camagüey and Santa Clara both cabecillas and troops were predominantly white.154 By rejecting the thesis of a race war, he distanced himself from the most prejudiced Autonomists. But his line of argument paralleled the Spanish and Autonomist propaganda that white control was necessary to prevent Afro-Cubans from rising up against whites. Once Weyler’s repression was in full swing, however, Morua gave up Autonomism and left Cuba for Tampa to support independence.

Indeed, the move from defensive protest against the insurgency to active mobilization for the defense of Spanish colonialism was a major step that a limited number of Afro-Cubans took. No doubt, a sense that their condition had not improved measurably neither after abolition nor after the mobilization for the conquest of equal rights behind the Directorio Central de las Sociedades de la Raza de Color explains why Afro-Cubans were a minority in the local forces that fought alongside the Spanish military in the war: the voluntarios, the bomberos (firemen), and the guerrilleros.

In fact, most active defenders of Spain belonged to the corps of voluntarios, which included almost no blacks. Significantly, in March 1896 José Bernabeu, president of the Casino Español de la Raza de Color in Havana, failed in his effort to form a battalion of voluntarios de color with members of pro-Spanish sociedades and cabildos de nación.155 The powerful, armed voluntario units were mostly made up of Spanish-born shop assistants, clerks, policemen, waiters, messengers, stevedores, boatmen, and laborers recruited by merchants and businessmen to defend the interests of Spain and business in Cuba. Voluntarios totaled about 63,000 by the end of 1895, though probably a substantial portion of them were only occasionally involved in fighting. As the war continued and better training became available, their contribution to the defense of Spain increased in numbers and efficiency.156

The corps of bomberos comprised Afro-Cubans only because of tradition. The firemen were an old colonial uniformed corps, composed of members of all classes and races of society, who assumed functions of vigilance and protection in towns. It nevertheless took all Weyler’s powers to put together one Afro-Cuban unit at the active service of the Crown. Following the 1890 strategy of Polavieja in Santiago de Cuba, in November 1896 he mobilized three hundred Afro-Cuban bomberos under the command of a black colonel for his western campaign against Antonio Maceo. In addition, out of this force Weyler “selected thirty of color . . . to form my escort, as a political means and to show my confidence in that race, so fond of Spain in other times.” He appointed the black sergeant Pedroso, “of gigantic height and Herculean strength,” to command the escort. When he returned triumphant to Havana after Maceo’s death, surrounded by his black bomberos, Weyler claimed that he so impressed the Casino Espanol de la Raza de Color that its members again asked permission to organize a battalion of color. Whether they succeeded this time is unknown.157

Finally, the pro-Spanish guerrillas recruited white Cubans and Spaniards as well as Afro-Cubans.158 Most guerrilleros came from the countryside, though some observers claimed they were criminals released from jail.159 Under the command of a Spanish officer or a local policeman, these improvised units served to protect villages and towns from insurgent attacks and to reconnoiter for the Spanish army. As the latter was unable to finance their rations, they also roamed the country pillaging farms and bohíos. Probably less than four thousand in late 1895, the number of guerrilleros increased in February 1896, after Weyler decreed the forced reconcentration of the rural population in Spanish-controlled camps. Although Weyler’s rural policy mainly prompted an exodus of peasants to insurgent ranks, it also caused peasant men to join the guerrilla units in order to avoid reconcentration— and sometimes these men deserted to the rebels later.160