Introduction: Southern Water, Southern Power

Over the course of three years beginning in 2006, the Southeast faced the worst drought in its history. As rain stopped falling from the sky from northern Alabama to central North Carolina, rivers dried up, and residents of the southeastern part of the United States nervously watched water levels in reservoirs drop dramatically. The lack of rain and diminished river flows so alarmed energy producers and regulators from seven states that representatives from five investor-owned energy companies, five public energy generators, and multiple federal agencies quietly convened at Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport to discuss how to keep the lights on and avoid rolling blackouts.1 In the South, water and power were inextricably connected.

The drought also stressed municipal drinking water supplies in momentous ways in 2007. One small Tennessee community’s water source—a deep well—went dry, forcing the town to truck in water. By November, other communities—including North Carolina’s capital, Raleigh—reported having only a three-month or less supply of water on hand. Southeastern residents unaccustomed to urban drought were clearly anxious; at least one Atlanta homeowner stockpiled thirty-six five-gallon water jugs in his basement. But the most visible consequence of the drought in Georgia—and a persistent source of local anxiety, regional conflict, and national media attention—was the growing ring of red clay around a blue reservoir named Lake Lanier.2

Located in northern Georgia, Lake Lanier is responsible for meeting the water needs of upward of 3 million metro Atlanta residents plus millions of people and countless uses farther downstream. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps), the federal agency responsible for managing Buford Dam, which impounds Lake Lanier, was releasing water from the dam into the Chattahoochee River to meet downstream needs in Alabama, Florida, and Georgia and to comply with federal laws. Besides meeting Atlanta’s water purposes, Lake Lanier’s regulated releases from Buford Dam were crucial to wastewater assimilation for dozens of communities; golf course and agricultural irrigation; industrial consumers like Coca Cola and Pepsi Co.; electric generation at hydro, coal, and nuclear facilities owned and operated by the Atlanta-based Southern Company’s subsidiaries; and commercial and endangered aquatic species in Florida’s Apalachicola River and Bay.3 If Lake Lanier or the Chattahoochee below Buford Dam dried up, then the consequences were real. Modern life in the booming Sun Belt would grind to a halt.

As the lake’s water level steadily dropped, Georgia officials grappled with a cascade of possible consequences for Lake Lanier and downstream needs if the drought were to continue. In an effort to nudge ordinary Georgians to save water, Governor Sonny Perdue declared October 2007 “Take a Shorter Shower Month.” The state’s Environmental Protection Division prohibited all outdoor watering in 61 of the state’s 159 counties as the region’s worst drought in history got even worse.4 These state mandates helped preserve the region’s water supply and sparked a culture of conservation among Georgia’s citizens, but by the end of 2007 Lake Lanier was still eighteen feet below “full pool.” State requirements, federal agency decisions, and human behavior alone could not refill the region’s streams, rivers, and working reservoirs.

After three dry years, the region rebounded vividly. In September 2009, a series of storms dropped fifteen to twenty inches of rain throughout metro Atlanta in one seventy-two-hour period. Lake Lanier—drained to its record low point in December 2007—gained three feet alone during the September 2009 rainstorms. Yet these gains came with significant costs. Multiple Atlanta suburbs—from the affluent homes in Buckhead to manufactured “mobile” homes in Cobb County—flooded when area creeks and streams poured out of their banks during the cloudbursts. Authorities closed multiple interstate highways when the flooding Chattahoochee River washed over and submerged bridges. Officials blamed at least ten deaths on flooding and more than $500 million in damages on what experts now considered one of metro Atlanta’s worst floods on record. In what became one of the state’s wettest years, the rest of 2009’s record rainfalls refilled Lanier, and the massive artificial lake reached full pool and pre-drought levels by October.5 As reliant as the water levels in rivers and artificial lakes were on the vagaries of the weather, southerners were also very much responsible for their own water choices.

While Georgians and their neighbors suffered through a major swing from drought to flooding, a U.S. district court judge issued a ruling that made the region’s water insecurity even worse. In July 2009, Judge Paul Magnuson determined that Congress had never authorized Lake Lanier to store municipal drinking water and that some metro Atlanta communities were illegally tapping the federal reservoir. Judge Magnuson ordered the Corps’ engineers to reduce municipal water withdrawals from Lake Lanier to 1970s levels by July 2012 unless Alabama, Florida, and Georgia approved an Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River compact to end a twenty-year-long conflict over allocation of water between the three states—popularly referred to as a tristate water war. Though this order has since been overturned (and was subsequently appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case), at the time the judge’s strict interpretation of legal and political history suggested Congress had only authorized construction of the Lake Lanier reservoir and Buford Dam project in the 1940s for flood control, to produce hydropower, and to regulate stream flows for downstream navigation and other benefits. Even Atlanta’s well-known Mayor William B. Hartsfield clearly understood congressional and the Corps’ intent for Lake Lanier. He quipped before a Senate subcommittee in 1948 that Atlanta needed a reliable water supply, but the city was “not in the same category” as cities “in arid places in the West.”6

Within days of Magnuson’s 2009 legal order, Georgia’s power struggle over water intensified. Metro Atlanta, a region comprised of over a dozen counties and more than 5 million people, had already been short of its water needs before Judge Magnuson’s ruling. Governor Sonny Perdue launched a multiple-front response that exacerbated long-standing intrastate tensions. First, Governor Perdue drafted Michael Garrett, then the Georgia Power Company’s CEO, to “quarterback” the state’s response. This selection was calculated to unify and mobilize Georgia’s corporate and utility interests, the stakeholders with the most to lose from heightened water insecurity—and with the most leverage on the local, state, and national levels. Garrett had climbed corporate ladders in the Southern Company’s subsidiaries, with management and executive tours of duty in the eighty-year-old Atlanta-based corporation’s even older subsidiaries: Alabama Power (established 1912) and Mississippi Power (1924).7 Second, Perdue also hastily assembled a Water Contingency Task Force. Cochaired by Coca-Cola Enterprises’ CEO John Brock and loaded with eighty-eight individuals who primarily represented metro Atlanta’s corporate interests (including Home Depot, Delta Air Lines, Sun Trust Bank, Georgia-Pacific, and UPS), the task force looked around the state for solutions to Atlanta’s impending municipal water shortage. After holding a series of closed-door meetings that legally barred public participation, the powerful task force released an official report on water supply alternatives for the sprawling southern megalopolis that brought all of the state’s working rivers and reservoirs into sharp focus.8

The Task Force’s December 2009 report provided Governor Perdue with a lengthy list of options to resolve metro Atlanta’s future water supply challenges. One element of the report also ignited a “two Georgias” rhetoric that has forever pitted metro Atlanta against the rest of the state.9 Among water supply choices—including “no regret” conservation measures, new water supply reservoirs, and desalination—the task force also evaluated interbasin transfers that could pipe water from the numerous corporate and federal reservoirs found throughout the state’s hinterlands to slake metro Atlanta’s core thirst. Two of the task force’s potential tools specifically targeted the Savannah River valley’s water resources and raised eyebrows. One of the interbasin transfer options would have pumped 50 million gallons of raw water per day from the Georgia Power Company’s Lake Burton—constructed in the 1920s to store Tallulah River water and generate hydroelectricity, and now surrounded by million-dollar homes—over a low ridge that divides the Savannah and Chattahoochee River basins. Pumps, pipes, and creeks would direct the Savannah River basin’s raw water into the Chattahoochee River basin and metro Atlanta’s municipal water treatment and distribution systems some seventy miles distant. Another task force idea included a 100-million-gallons-per-day water withdrawal from the Corps’ Lake Hartwell and hydroelectric dam project in rural Elbert County, also in the Savannah River basin. After pulling water from Lake Hartwell, the pumps would transmit water over rolling hills and shallow valleys via an eighty-mile pipeline to suburban Gwinnett County in metro Atlanta.10 When skeptical boosters, elected officials, and newspaper editors from downstream cities and rural parts of the state discovered the interbasin transfers would tap their local rivers and water sources, they reminded constituents and readers that “Metro Atlanta wants Augusta’s water” and told Atlanta to keep its “hands off the Savannah River.”11 Atlantans’ demands—like those discussed in the task force’s report—have historically pulled, with the strength of a tractor beam, the surrounding hinterlands and their natural resources into the city’s orbit.

The “two Georgias” oratory amounted to more than simple political theater. During the 2010 General Assembly session, the Georgia state legislature and environmental agencies never actually considered specific interbasin transfers to resolve metro Atlanta’s then-critical water problem. But the governor’s Water Contingency Task Force menu motivated hinterland legislators—including at least 24 state senators (of 54) and 68 representatives (of 180)—to support legislation that would have made it difficult to transfer large quantities of water over great distances to water lawns and fill swimming pools in Atlanta.12 The interbasin transfer legislation, however, stalled and died when a Senate Natural Resources and Environment Committee chairman refused to allow the bill out of committee or onto the floor for a full Senate vote knowing the bill would pass by a wide margin.13 Amidst the worst drought in history, a destructive bout of flooding, and the prospect of new legal restrictions on the use of water from Lake Lanier, legislators jousted over theoretical projects that would have increased water insecurity throughout the region.

This high level of anxiety in a water-rich region was perplexing to me. For all of my adult life I have driven across and flown over the southeastern United States, and for the last decade I have researched the history of the region’s relationship with its waterways. It is hard to go anywhere in the Piedmont or Blue Ridge and not find a stream, river, or big pool of water. Early on I discovered that all of the Southeast’s major lakes not only are artificial, but many are privately managed. This basic fact sets the Southeast’s history of water and power—of water supply, users, and rights—apart from other regions of the United States. As I studied the history of the region’s hydraulic waterscape, the drought intensified, and I wondered why the Piedmont—a place with an average of forty-five to fifty inches of rain and a long agricultural legacy, as well as a documented history of flooding—was suffering. Why was a place dotted with lakes and known for its cotton, peaches, peanuts, humidity, swamps, and malaria embroiled in intrastate and regional conflicts typically associated with Los Angeles and Las Vegas in the Colorado River basin, or with California’s and Idaho’s irrigated valleys?

For a long time, the primary southern response to water problems was to bend rivers to meet human demands. As such, water problems—not unlike many other southern problems—involved solutions that were typically resolved only to meet very specific ends and created new problems.14 Fickle water supplies, multistate water wars, and interbasin transfer regulation, as my own inquiry revealed, are actually modern acts in the region’s long-running environmental history.

Southern Water, Southern Power focuses on one region where Americans deployed political power to control conversations about water supplies and river manipulation. But this is also a national story about American individualism, equity, and the contest to define what constitutes the proper use of common natural resources. This environmental history of the Southeast illustrates the central role that water played in shaping human choices and physical landscapes. The parties and interests who drove many of these changes had three primary goals: to produce energy, to build a modern South, and to resolve water insecurity brought about by flooding and recurrent drought.

First and foremost, southerners made choices to control water resources in conjunction with their energy decisions. The region has historically lacked abundant coal, natural gas, and other forms of energy. Put another way, the Southeast’s hydraulic waterscapes—the hydroelectric dams, transmission lines, and reservoirs with their associated leisure economies—have been inscribed with social and cultural meaning; the waterscapes tied together the demands for water and energy, and eventually flood control, drought management, and other environmental services.15 But it all started with an energy-water nexus that has left an indelible footprint on the region’s cultural and natural history.

When it comes to conversations about energy history and policy today, the fossil and mineral fuels—coal, petroleum, natural gas, and uranium—drive the discussion.16 The energy-water nexus—or the direct relationship between water supplies and energy production—adds a new twist and has recently emerged as one of the nation’s more vexing future challenges. According to the Department of Energy’s Sandia National Laboratories, “The continued security and economic health of the United States depends on a sustainable supply of both energy and water. These two critical resources are inextricably and reciprocally linked; the production of energy requires large volumes of water while the treatment and distribution of water is equally dependent upon readily available, low-cost energy.”17 The energy-water nexus affects national energy producers, municipal water suppliers, agriculturalists, environmental health, and every American who turns on a faucet or flips a light switch. In the Southeast, water was always a critical ingredient in energy production for antebellum waterwheels, New South and New Deal hydroelectric dams, and Sun Belt coal burners and nuclear reactors. Waterwheels and hydroelectric facilities relied on falling water to turn turbines to generate organic energy for centuries, and fossil fuel and nuclear plants transform liquid water into steam to make electricity. Without water, it would have been—and will be—nearly impossible to produce all the energy and products required by consumers and for economic development. Furthermore, the culturally defined and politically managed energy and water connection has been complicated by physical environmental conditions.

The second critical element to understanding southern environmental history is a reckoning of how people responded to water insecurity. The following narrative demonstrates why Georgia’s dramatic 2007 drought and flooding events of 2009 were not isolated moments of water insecurity. The Southeast’s rural and urban political economy has always contended with these issues. In 1912, for example, a northeast Georgia newspaper columnist sympathized with a movement to save the beautiful Tallulah River and the majestic Tallulah Falls that were slated for destruction. The Georgia Power Company was planning—and eventually completed—a hydroelectric dam to produce electricity “to turn Atlanta’s wheels” ninety miles away.18 During the response to the 2007 drought, the Georgians who worried about interbasin transfers taking water from Lakes Burton or Hartwell to benefit Atlanta understood—as those did in 1912—that energy, geography, and power connected water-rich hinterlands to millions of people in a resource-poor core dependent on unreliable water supplies in a humid region once assumed to have plenty of water. Until the last few decades when Georgia agriculture blossomed into a multibillion-dollar sector, the humid Southeast’s water and power history has been primarily a story about urban and industrial power.

Finally, the example of Georgia’s powerful shifts from record droughts to record floods illustrates how water insecurity has been manufactured and was only partly natural throughout southern environmental history. Twin risks—flooding and drought—have been present and persistent across the region for some time. There are many interpretations of flooding in the Southeast, yet there are surprisingly few published histories of agricultural and urban drought.19 The political economy evolved to manage too much or too little water because these environmental conditions generated economic uncertainty and social conflict. But the risk management solutions for drought and flooding created a false sense of security. Drought, of course, is only partly a natural disaster. Meteorological drought is a normal climatic condition caused by a lack of rainfall over prolonged periods. This type of drought has occurred for millennia and only became a cultural problem when the lack of rainfall reduced the availability of water supplies and limited human choices.

Yet drought, like many other natural disasters identified by historian Ted Steinberg, can reveal “human complicity” in constructing a landscape subject to nature’s whim and fury where the human victims in earthquakes, tropical storms, and flooding were often powerless and the beneficiaries were often economically powerful. On many occasions, Georgians had considered disasters like inland flooding, tropical storms, and punishing droughts to be localized natural disasters that wreaked unavoidable havoc, thereby threatening human life and economic progress. The solutions for weathering disasters—while couched as serving the public good—often produced future risk and benefited very specific constituencies. For example, levees historically solved local flooding issues but exacerbated problems for adjacent and unleveed communities in subsequent floods. Deeper water wells and more reservoirs also resolved local municipal water supply shortages during droughts for the short term, but problems reemerged in the future as population and demand outstripped supply. In both examples, risk management solutions generated by a small number of decision makers intent on avoiding future natural disasters created a false sense of security and manufactured future risk.20

Southeastern water problems—as creations and natural phenomena—cannot be separated from energy choices, the region’s political economy, and mercurial environmental conditions. Water quantity and quality were always critical ingredients for energy production and political calculations but have always been changeable natural elements. Southern Water, Southern Power takes a long view of southern rivers and modernization, asking who altered the region’s waterways and what environmental conditions inspired them to act.

The late journalist and environmental writer Marc Reisner observed that the “reasons behind the South’s infatuation with dams was somewhat elusive.” In his critical and much-admired history of water and power in the arid American West, Cadillac Desert, Reisner repeatedly demonstrated how boosters, engineers, and politicians made water flow over mountains to moneyed interests. He was just one of many writers to interpret the American West’s complicated history of water and power.21 In a brief detour to the American South, Reisner noted the different types of structures, from “water-supply reservoirs and small power dams” to “a handful of mammoth structures backing up twenty-mile artificial lakes.” The Southeast had a high annual precipitation rate and a history of devastating floods and was well known in Mark Twain’s Mississippi riverboat narratives. In describing the region’s humidity, as well as the hydroelectric dams and channelized rivers that moved water and vessels efficiently, Reisner identified the complexity of the Southeast’s water problems, economic past, and social relations.22

Much has been written about southern rivers from the perspective of river admirers, corporate historians, and nature writers.23 Academic scholars have also explained the rise of the New South (1890–1930) from the perspectives of capital flows, branch offices, regional upstarts, industrial geography, local governments, planters, industrialists, and boosters in an effort to explain the region’s industrial and urban growth as processes of change and continuity.24 Pathbreaking research has revealed the degrees to which industrial managers and workers manipulated one another within one critical sector—the textile industry—to demonstrate the important social and political consequences of economic development.25 Others have credited federal stimulus and liberal local incentives with the rise of the industrial New South and post-1945 Sun Belt eras.26 Connected to this memory, which is as important as it is problematic, are histories centered around the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) that insinuate that only the federal government manipulated southeastern rivers with large hydroelectric dams to stimulate the southern economy and primarily did so only during the New Deal (1933–44). Focus on the TVA has obscured the New South activity before the Great Depression and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ critical role after World War II.27 Nearly all observers have presented only casual links between cheap human power and cheap natural power to explain the region’s growth. In an important exception, scholars observed the nexus of water and power in the coercive southern institution of slavery. Coastal Plain rice plantations had depended on southern tidal rivers and African American slave labor to supply the technical forces and environmental knowledge necessary for crop survival. However, after the American Civil War and without slave labor, the planters’ “hydraulic machine” fell apart as emancipated laborers walked away from the rice fields, the rivers washed away protective dikes, and rice cultivation was no longer economically viable.28

Climate, topography, and environmental conditions have mattered in southeastern environmental history, but even here, the Mississippi River and the Deep South have received the lion’s share of attention.29 The other side of this climatic coin, drought, has equally influenced the region’s history and is dismayingly absent from public memory.30 In the first half of the twentieth century alone, droughts reduced agricultural production, limited industrial operations, required suburbanites to conserve water and energy at home, and affected urban centers far removed from water sources.31 After these agricultural and urban droughts, energy executives diversified company generation technologies, local governments raised taxes to increase water supply capacity, and federal engineers replumbed the southeastern waterscape on a massive scale across the Piedmont South from Alabama to Virginia.

From an airplane flyover or a Google Earth screen shot, the American South looks not unlike the arid American West. Dense urban cores and cul-de-sac suburbs give way to a patchwork of agricultural communities, open space, and steeper terrain. From the sky, the South reveals a distinct similarity to parts of the arid West in the presence of artificial waterworks such as dams, ponds, and reservoirs. Large and small reservoirs now dot the landscape from Mississippi east to Georgia and north through the Carolinas. (Only within the last thirty years have circular green patches in southern Georgia begun to appear, indicating the presence of groundwater pumping and center-pivot irrigated farming once isolated to the Great Plains.) On the ground and zoomed in, the most prominent evidence of human alteration of the regional environment remains thousands of aging ponds, impoundments, and reservoirs of varying size and shape.32 Corporate players and state actors manipulated the Southeast’s river environments, and they engineered “Georgia’s Great Lakes,” small agricultural reservoirs, and rivers to overcome regional environmental conditions.33 The humid South, as Marc Reisner intimated in Cadillac Desert, was no more monochromatic than the American West, where a diversity of social and environmental realities produced a range of water management solutions in the Colorado, Sacramento, and Columbia River basins. Reisner was on to something, but he had only scratched the surface. Given the history and prominence of the American West, one is left to wonder why southern scholars, journalists, and observers have been so slow to notice the compelling similarity that Reisner saw as early as the 1990s. Understanding where southern reservoirs and artificial water structures came from, the corporations and state institutions who built them, and what purposes this manufactured waterscape has served unlocks an untold story about southern waterways and urban-industrial power.

Southern Water, Southern Power moves beyond the well-known histories of flooding in the Mississippi Valley and irrigation in the American West and places cheap energy and water insecurity at the center of the region’s political economy and transformation. In Southern Water, Southern Power, the rise of the New South cannot be disconnected from the genesis of the regional hydraulic waterscape. Beginning in the New South era, private corporations and transnational actors manipulated environmental conditions to produce energy decades before the arrival of a New Deal big dam consensus of the 1930s. During the Great Depression, flood and energy politics influenced New Deal liberalism and remapped southern communities far removed from the Tennessee River valley. And water and cheap energy also rested at the core of post–World War II Sun Belt economic development, conservative politics, and recreation planning. Regardless of time and place, the people and institutions that put these changes in motion learned repeatedly how their power would be challenged by their competitors, customers, constituents, and nature. And above all, the floods and droughts—the slower, forgotten, but no less economically damaging regional water problem—considerably influenced New South, New Deal, and Sun Belt history.

When I started this project, I thought about specific rivers—the Tennessee, Catawba, Savannah, Chattahoochee, Coosa, Alabama, and Tombigbee—that had figured prominently in the region’s history as transportation conduits or because of their capacity to flood and induce human suffering. Southern lakes and droughts, I soon learned, had received far less attention despite their direct connection to some of those same rivers and the region’s political economy. Only one of the Southeast’s three physiographic provinces hosts what one might call “lakes,” though midwesterners and New Englanders might not recognize them. For example, the Southeast as a whole is home to alluvial “oxbow” and natural lakes cut off from river channels in the Coastal Plain. Furthermore, shallow “Carolina Bays” on the southeastern Coastal Plain can be considered lakes, but according to one scientist, “No clear consensus has been reached regarding the complex issue of the origin of” these bodies of water.34 There is, however, consensus on the origin of the lakes in the Piedmont and Blue Ridge mountain physiographic provinces. New South capitalists, New Deal regional planners, and Sun Belt boosters coordinated the construction of large artificial reservoirs in these two physiographic provinces to spur industrial development, consolidate or challenge corporate power, and deliver a multitude of economic and social benefits to urban customers, rural citizens, leisure seekers, and shareholders. In the process of assembling this extensive hydraulic waterscape, corporate and state operatives attempted to conquer environmental conditions such as flooding, drought, and a lack of quality indigenous fossil and mineral fuel sources.

After I looked at the rivers, dams, and reservoirs, the deep and rich story about water and power in the U.S. South became more evident. Not only is this a history of waterways and environmental change; it is also a story about how private corporations, public institutions, and citizens challenged one another to manage natural resources equitably while stimulating and sustaining economic growth. As artifacts, the elements of the modern Southeast’s hydraulic waterscape illustrate a complex flooding, drought, and energy history and demonstrate some of the ways that southerners have responded to the region’s environmental and social struggles. Old water problems and energy choices consistently stirred up political friction and contributed to building new working, living, and leisure environments during the New South, New Deal, and Sun Belt eras.

The Savannah River, which forms the boundary between South Carolina and Georgia, perfectly illustrates how people negotiated regional water insecurity and attempted to bend rivers to meet human demands throughout the U.S. South. I focus primarily on the Piedmont Province and to a lesser degree the Blue Ridge physiographic regions because people shaped valleys in these sections on a more substantial scale than they did on the Coastal Plain.35 No waterway—in the Southeast or elsewhere—has the same history. Some have important flood, navigational, or recreational stories. For other rivers, private and federal agents’ singular focus was to turn river currents into useable energy. If each of these individual river stories represents a tributary, they all flow together in the Savannah’s basin to tell multiple river stories in a single Piedmont space. As such, the Savannah River presents a case study in the broadest sense; other river valleys throughout the region witnessed or were subjected to individual private and public water management schemes. However, no other regional watershed can showcase all of those schemes in one geographic place like the Savannah.

People dramatically altered the Savannah River and other southeastern valleys after the mid-nineteenth century to solve the region’s recurring water problems and meet culturally defined energy needs primarily for urban and industrial applications. In the first of three formative periods, a cast of influential characters from corporate institutions initiated a privately financed dam and reservoir building program to spur economic development and meet expanding energy demands during the critical New South moment (1890–1930). Corporate titans, free-market capitalists, and transnational engineers built an extensive network of hydroelectric dams, backup coal plants, and textile villages in the heart of the southern Piedmont, and they connected these nodes of production and consumption with an elaborate system of overhead transmission lines. Emergent energy companies and the textile industry attempted to control rivers and former agricultural workers, and in the process they blended the region’s water, labor, and racial problems. These independent and often multistate energy conglomerates operated above and beyond traditional political boundaries, deployed corporate and electrical power to build regional monopolies, and demarcated the New South’s territory with high-tension electric power lines. At the beginning of the twentieth century, urban and industrial centers emerged as white and black southerners left fields for factories in Atlanta, Charlotte, and towns of varying sizes. Energy—human and hydroelectric—made the era’s spectacular industrial growth possible. But within two decades, a multiyear regional drought brought this mushrooming hydraulic waterscape and the New South to its knees between 1925 and 1927. Additionally, the drought revealed the danger of technological plateaus where producers and consumers relied entirely on renewable and organic energy sources such as water. As the record drought ended, the region’s energy brokers bridged a technological gap in the first of many electric generation upscalings. But even as they shifted from organic and hydroelectric generation to fossil fuels and thermoelectric generation in coal-burning plants, operators and clients could never distance themselves from southern rivers. Executives in boardrooms, residents in cities, and mill workers, it appeared, could not escape—without significant external assistance—water problems within a New South bound together by transmission lines and rivers like the Savannah and its tributaries.

During a second period, between 1930 and 1944, the legacies of New South capitalism shaped New Deal liberalism as Americans redesigned the nation’s waterways during depression and war. A combination of economic and environmental factors altered the fate of southeastern rivers and highlighted the difficulty in determining who—corporate players or state agents—was better equipped to manage the region’s water and energy future more equitably. For example, after the 1920s drought, disastrous floods swept the nation from the Mississippi to the Ohio and the Savannah. As the Great Mississippi Flood (1927) wreaked havoc and captivated media attention, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was undergoing an institutional transition the deluge cemented. At the time of the flood, Corps engineers were already evaluating the capacity of the nation’s rivers to produce hydroelectric energy, to irrigate fields, and to meet other comprehensive needs. Soon after the Great Mississippi Flood, Congress conferred all river management activities—defense, navigation, and flood control—upon the Corps and asked the institution to continue surveying the nation’s rivers. Along the Savannah River, two serious droughts bracketed a major flood while the Corps appraised the valley. On the tail of the 1920s record drought, record Savannah River flooding in October 1929 revealed the inequity of river management and ruptured communities while exposing one Georgia city’s racial geography. Drought, flooding, and the global Great Depression dealt New South capitalism a collective blow and opened the door for a new alternative.

The federal initiative to control environmental conditions in the nation’s river valleys dovetailed with liberal New Dealers’ motivation to challenge the corporate and monopolistic models that had claimed these rivers decades earlier in the name of industrial development. The New Dealers’ quest to anchor economic liberalism and decentralize industrial development began in Tennessee, where they launched the TVA (1933) to limit monopoly power in the energy sector and to improve southern social and environmental conditions. The TVA institutionalized a New Deal big dam consensus whereby large multiple-purpose dams joined flood control, energy production, and agricultural improvement. When this regional planning and New Deal big dam consensus encountered resistance, bipartisan conservatives blew new life into old agencies, namely the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. With new power and New Deal experience, the Corps divorced TVA regional planning and the trio of dam benefits that improved navigation, generated electricity, and provided flood protection. Southern Democrats repackaged New Deal liberalism and turned the Savannah River valley’s environmental manipulation over to the Corps after 1944. Corps engineers emerged—uncomfortably—as the new arbiters responsible for balancing the legacies of New South laissez-faire and New Deal liberalism to meet the Sun Belt’s energy and water demands.

In the final and third, post-1945 river development period, Sun Belt corporate and state institutions sparred over how best to approach the water and energy challenges in the Savannah and other river valleys in order to serve urban and industrial consumers. Unlike the flurry of corporate projects completed during the critical New South period and the liberal New Dealers’ unrepeated TVA model, the Corps burst upon the scene and became the Sun Belt’s primary water and power broker. In the Savannah River valley alone, the Corps completed three massive multiple purpose dam and reservoir projects in a publicly funded attempt to solve the region’s water challenges and redefine regional power. Nearly all southern politicians, community leaders, and ever-present boosters initially invited and welcomed these injections of federal economic development dollars. The corporate energy producers, however, did not, and they challenged “public power.”

Opposition to the Corps arose on many other fronts. Energy executives and their allies in Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina continued to build new projects. They also objected to federal energy programs that resembled retro–New Deal liberal initiatives or represented threats to Sun Belt free enterprise. Discussion of water rights emerged as a critical concern among conservatives after the 1950s drought and the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education (1954) order to desegregate schools and public facilities, including recreational destinations. In this postwar climate, the Democratic Party’s fracture lines widened and the New Deal big dam consensuses’ once-formidable list of supporters shrank. Sun Belt boosters and Democrats worked tirelessly to wrangle federal dollars, but plans for public power and multiple-purpose dams began to crumble in the 1960s. The New Deal big dam consensus, however, was wounded by more than push-back from Sun Belt corporations and conservative critics.

After 1945, a cross section of Sun Belt citizens emerged from the grass roots. These southerners registered complaints in response to the Corps’ real estate, reservoir management, water quality, economic, and environmental policies. Not all criticism was unfounded. In a refrain that would repeat itself throughout the Corps’ existence, officers and engineers took on tasks to complete their dam and reservoir plans for which they were not entirely prepared. When corporate engineers and New Dealers built power projects before 1945, they treated water quantity as the primary environmental challenge. Water “conservation” was a risk management activity devoted to storing floods and producing additional water supplies to outlast future droughts. After 1945, the Corps’ last Savannah River valley big dam demonstrated how the national conversation about waterways, urban-industrial energy, and pollution had shifted. By the 1970s, Congress was dismantling the multiple-purpose trio of benefits of the New Deal’s big dam consensus, and the function of free-flowing water influenced the Corps’ final Savannah River valley project. Countryside conservationists and environmentalists demanded a new environmental accounting from Sun Belt commercial promoters, and they valued water quality in the shadows of hydroelectric dams and water storage reservoirs inspired by New South capitalism and New Deal liberalism.

Out of this New-South-to-Sun-Belt water and power history, one special river in the Savannah River basin was spared. As countryside conservationists and environmentalists around the nation and the Sun Belt mobilized in the 1960s, they looked at rivers such as the Chattooga as examples of undammed, wild, and scenic rivers worthy of federal protection. The Chattooga River—James Dickey’s Deliverance river—encapsulates the American South’s nearly century-long water and energy history. Whereas the Georgia Power Company had built a hydraulic system to expropriate energy from northeastern Georgia rivers in the 1920s, the company delivered the adjacent Chattooga River to the environmental and paddling community for safekeeping in the 1960s for a variety of reasons. By the 1960s the company had abandoned the hydroelectric dams it had first proposed during the New South era and favored Sun Belt nuclear-generated electricity to save the nation from an anticipated energy famine. Not all of the Sun Belt’s water problems could be solved so easily, but the Chattooga River’s history illustrates how water and power continued to cycle in the region with important consequences for southeastern rivers, energy, and environments.

The political economy of water and environmental conditions shaped the history of the Southeast’s inland waterways. Recurrent floods and droughts challenged energy companies and dam builders in ways that made empire building impossible and controlling labor difficult in the southern Piedmont’s hydraulic waterscape. A history of the material environment of the Savannah River and other river valleys reminds us that how people talked about and constructed ideas about “Nature” was as important as how they lived with, adapted to, and claimed the valley’s physical water resources over time. Southeastern waterways—from the Catawba and Alabama to the Tennessee and Chattahoochee—have individual histories that are best embodied by the Savannah River’s physical geography. Valley residents and investors certainly valued the river and its beauty, waterpower, flood control, and navigational utility, but they never fully commodified water or rationalized a system subject to intense flooding and cyclical drought. Rather, engineers responded to floods and droughts with reservoirs and other technologies to meet specific political and economic needs in exact historical moments. All too often, their solutions prompted new debates, incited social conflict, generated more demand, and manufactured future risk. Throughout the past and in today’s contemporary context, these reservoirs and structures inflated expectations and oversold benefits while water challenges persisted. The U.S. South’s working reservoirs are indeed human creations and technological artifacts and thus do not behave entirely like natural or static lakes. In these storied waters, hatchery-raised bass run for fishing tournaments, invasive aquatic grasses like hydrilla bloom, pollution-laden sediment settles, and water levels can fluctuate widely. In this framework, the artificial reservoirs perform cultural and environmental functions, but not necessarily functions for which the projects were originally designed. As the more recent droughts, floods, and Lake Lanier’s fluctuating water level demonstrate, people’s expectations of the region’s reservoirs have shifted in a postindustrial society, while the insecurity induced by unpredictable drought or flooding remains basically the same. Today, as in the past, equitable distribution of a valuable natural resource once assumed to be plentiful remains at the center of the region’s modern conflict.

This project has no intention of furthering a myth of “southern exceptionalism” or environmental determinism. A history of the Southeast’s hydraulic waterscape demonstrates how this particular natural resource was a critical element in conversations and choices about how to build a modern, urban, and industrial society. As in other regions of the United States, people shaped the American South’s historical experience through the selective application of technology and concentration of capital in the process of responding to shifting environmental realities. The existing water history has treated the American West’s water insecurity as exceptional, and nonhistorians have been responsible for dismantling this myth. By historicizing the American South’s water and energy past, I simultaneously hold the region apart to explain what makes southern water and power choices different while bringing the region into the larger discussion about the nation’s energy-water nexus and water supply future.36

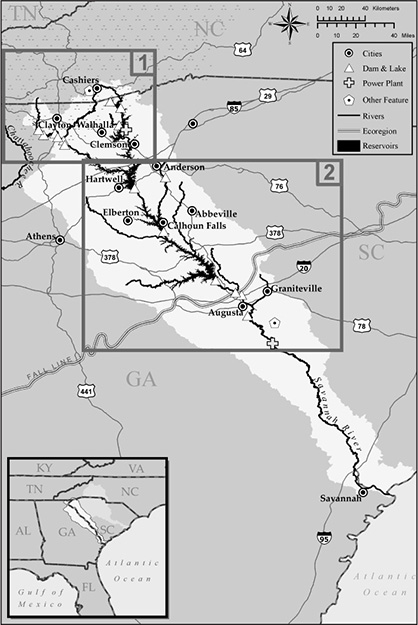

Savannah River basin, 2013 (map by Amber R. Ignatius)

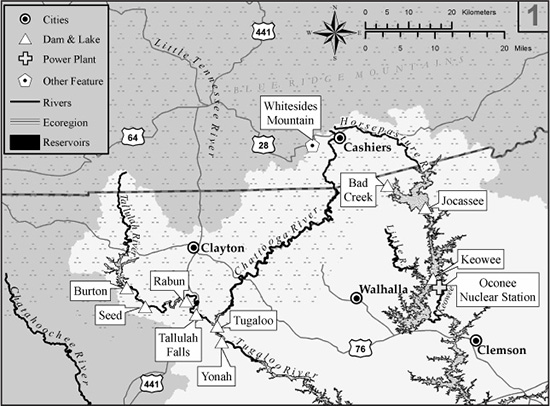

Upper Savannah River basin, 2013, showing selected Georgia Power and Duke Energy sites (map by Amber R. Ignatius)

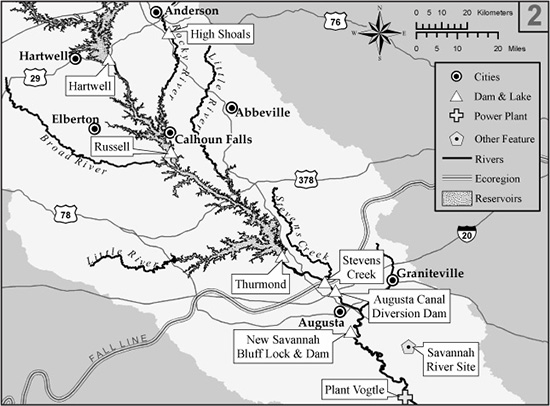

Middle Savannah River basin, 2013, showing selected sites (map by Amber R. Ignatius)

From the New South to the Sun Belt periods, water has been a critical part of the southeastern political economy. Community and regional leaders understood that power flowed from Piedmont and Blue Ridge rivers. Successful New South capitalists and political interests influenced the shape of New Deal liberalism and Sun Belt conservatism. Dams—as symbols of corporate monopoly or public works projects, or as providers of environmental services—frame the picture of this narrative. Energy demands and environmental conditions, including droughts and floods, rest in the heart of the historic and modern social conflict over urban-industrial development, consumer markets, and recreation space. Southern Water, Southern Power demonstrates how decisions informed by energy needs and water insecurity influenced physical and political landscapes.