Chapter 2: Dam Crazy for White Coal in the New South

In his 1932 book, Human Geography of the South: A Study in Regional Resources and Human Adequacy, Rupert Vance declared that “there are two great economic complexes that may be expected to force” states to abandon selfish or provincial attitudes in exchange for regional or national outlooks. Vance’s study provided solutions for building a modern region and challenging long-standing assumptions that the South was a colonial outpost bedeviled by race relations and that it could be nothing more than a poor land inhabited by poor people. Born in Arkansas, Vance contributed to the liberal strain of regionalist analysis at the University of North Carolina in the 1930s; he saw a way out of the regional backwardness as the United States entered the global Great Depression. As the first complex, Vance considered continued railroad network development for connecting crops and peripheries to markets and central cores. More recently, scholars have examined the economic, cultural, and environmental consequences of America’s railroads and have demonstrated that transportation and technical systems integrated those regions into the national fabric. But Vance’s second complex, hydroelectric development in the humid and generally water-blessed Southeast, is still poorly understood as a force of change in the first three decades of the twentieth century. In a region well-endowed with flowing water, Vance argued, rivers were prime renewable energy resources that could be “harnessed” to benefit farmers and factory workers. Vance’s travels and collaborative research throughout the Southeast revealed an extensive privately capitalized network of hydroelectric dams, reservoirs, and transmission lines that stretched from North Carolina to Mississippi. Relying on these observations, Vance advocated for a publicly funded and publicly owned regional hydro-complex that mimicked the private energy corporations’ modern systems. When Vance looked across the “Piedmont crescent of industry” one year before President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in 1933, water appeared as one of the most underutilized natural resources and as a renewable energy source monopolized by a few private energy companies and industries. Vance saw the fruits and inequity of the New South economy, and he embraced hydroelectric power and cheap organic energy as tools to shape a new future.1

White coal, in Vance’s estimation, could redefine the New South’s relationship with the rest of the nation and improve southerners’ daily lives. Reassessing Rupert Vance’s ideas provides a new interpretation of southern modernization. First, regionalists such as Vance influenced the shape of the TVA and liberal New Deal river development in the 1930s. Second, the TVA project inspired subsequent federal waterway and energy programs in the Southeast and across the nation after 1945. But more important, Vance opens a window into an early period of regional modernization that has been overshadowed by the TVA’s high-modernist experience, by repeated assertions that the South was the nation’s top economic problem, and by the federal largesse that built the Sun Belt after 1945.

This chapter examines who hitched the New South to white coal in the Savannah and other river basins during a crucial period in the region’s history between 1890 and 1933. We should seek out the origins of Vance’s hydroelectric “complex” and “the Piedmont crescent of industry” because waterway manipulation and energy generation were critical components of southern modernization after the American Civil War. For millennia, human beings have produced energy from a variety of sources—primarily by burning biomass (peat moss or trees) and fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas). During the nineteenth-century industrial revolution, people around the world began producing energy by burning fossil fuels with the express intent to transform boiling water into steam for locomotion and generation of electricity. By that time, regardless of the fossil fuel source, water was the critical component for generating energy in steam engine boilers on riverboats, in locomotives, and on factory floors. The Blue Ridge and Piedmont South, however, lacked economical access to coal, oil, and gas reserves necessary to fuel this watery transformation. Between 1890 and 1925, water, not burning fossil fuels, was the most important energy fuel source in the New South. Eager investors and glassy-eyed boosters like Henry Grady had generally assumed the Southeast—a humid place with many rivers—had all the water they could dream of.

Rupert Vance provides a launching point into the New South phase of southern water and power. Vance’s second great complex—hydroelectric technology driven by New South capitalists’ thirst for a privatized, indigenous, and cheap energy source—made energy corporations and southeastern rivers integral players in the region’s history. The New South was hardly exceptional, but the scale and degree by which the energy sector sustained industry with water-generated energy made the region uniquely powerful and vulnerable. James B. Duke, the tobacco king and private university benefactor and Vance’s most detailed example, started one of the most prolific energy companies that continues to operate more than 100 years later. Duke Power Company’s founding goal in 1904, according to the company’s namesake himself, was to harness “white coal” from rivers that previously flowed unused as “waste to the sea.”2 Today, the artifacts of the region’s hydraulic waterscape reveal much about the legacy of southern water and southern power in the decades before the advent of the TVA in 1933.

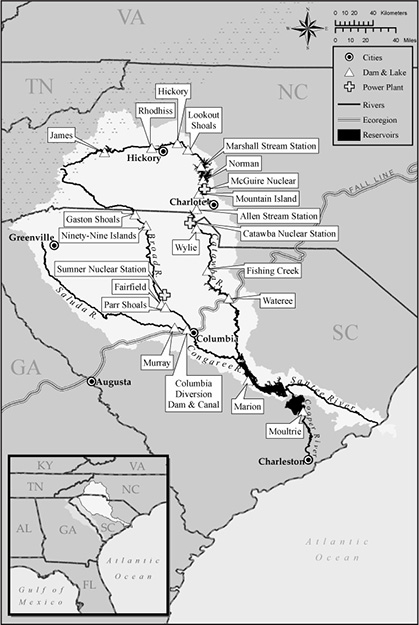

After 1900, New South energy companies invigorated the process of mill and town building that William Church Whitner contributed to in the 1890s in the upper reaches of the Savannah River valley. Numerous companies—including the independent Tennessee River Power, Alabama Power, Georgia Power, Duke Power, and other smaller companies—planned and developed multiple-dam and sometimes multiple-purpose projects across the region to redirect river energy to factory hands and machines. “Water power,” Rupert Vance declared in Human Geography, was “the one unifying force underlaying industrial development” in the southern Piedmont.3 Vance observed this development through North Carolina’s James B. Duke (1856–1925), and Duke Power Company was among the first and most successful corporate enterprises to couple waterpower and industrial development. Dr. Walker Gill Wylie (1849–1923), a South Carolina native, New York City physician, president of the Catawba Power Company, and Whitner’s former business partner, presented the self-made American Tobacco Company king with the idea of developing a series of hydroelectric dams and reservoirs on the Catawba River.4 Together, Wylie and Duke tapped William States Lee (1872–1934), a Citadel graduate and engineer who had previously worked alongside Whitner at Portman Shoals and who had completed Wylie’s Rock Hill (S.C.) Catawba Power Company hydroelectric project in 1904, to provide the technical know-how.5 Not unlike other company founders who merged technical skill, river knowledge, and financial resources, the Duke trio started building a system in 1905 and within six years had linked four hydroelectric plants (three on the Catawba River) and two auxiliary coal-fired steam plants in the Carolina’s Piedmont.6 By then, Duke Power Company’s Catawba (Lake Wylie) and Great Falls projects stored water behind dams before turning falling river water into energy for distribution over 700 miles of transmission lines to reach more than 100 cotton mills.7

River basins in North and South Carolina, 2013, showing selected sites in the Saluda-Broad, Catawba-Wateree, and Santee-Cooper River basins (map by Amber R. Ignatius)

James B. Duke did not wait for markets to emerge to justify massive capital investments in hydropower; he cultivated industrial consumers. Duke’s company, and other companies that followed, had never envisioned providing service to rural or residential customers. Instead, as Duke historian Robert Durden has demonstrated, Duke invested directly in new textile mills or subsidized the electrical conversion of old mills to use electric equipment to ensure a market for his company’s electricity and to attract New England’s manufacturers to the Southeast. Industrial sociologist Harriet Herring, one of Vance’s Chapel Hill colleagues, concluded that Duke Power “became a veritable Chamber of Commerce in advertising the advantages of the area for manufacturing.” Duke Power’s influence was “more positive and concrete than any Chamber of Commerce,” in Herring’s opinion, since the company could “offer attractive inducements to potential customers” in the days before public utility commissions regulated utility rates and service areas. In another example of Duke’s influence, one company subsidiary, the Mill Power Supply Company, provided low-interest loans and ample credit to mill owners who abandoned the on-site steam plants they originally used to generate energy and converted to using energy produced and delivered by the Duke network. Duke Power executives were formidable economic players eager to feed the Piedmont’s industrial base with energy derived from a changing southern waterscape.8

So why did Duke and his contemporaries in the Southeast initially cast their lot with white coal instead of rock coal? The Northeast and Rocky Mountain West had turned to fossil fuels—heavy fuel oil and coal—before and after the American Civil War as canal, railroad, pipeline, and coal mining operations shared corporate ownership and evolved in tandem.9 Southeastern energy history was equally complicated and for different reasons. Pennsylvania, Alabama, and southwest Virginia miners cut bituminous coal for southern railroads, municipal waterworks, the metallurgical industry, the electric industry, and other heavy manufacturing regions stretching from the Carolinas to Texas that were coal and oil poor before the 1890s. New energy sources soon emerged as the clear winners in the early twentieth century, leading these regions to turn to alternative fossil or organic fuel sources. For example, Los Angeles and Houston declared energy independence from expensive coal imports from Canada, Australia, and Pennsylvania and tied their economic futures to locally available heavy fuel oil or natural gas after 1900.10

Southeastern railroads, factories, and homes certainly burned Alabama coal between 1890 and 1925, but coal was not yet king.11 Alabama was the only major coal-producing state south of Tennessee and Virginia, and in 1900, Alabama produced a mere 8.3 million tons of coal when national production hovered just under 270 million tons. By 1929, Alabama had increased production to 17.7 million tons when national production surpassed 600 million tons.12 And, Alabama’s coalfields primarily supplied the state’s Birmingham-centered metallurgical industry. At least one transnational railroad executive considered Alabama coal supplies unreliable and “of uneven quality” as locomotive fuel.13 Other southern cities, from Atlanta to Charlotte, were hamstrung by coal’s freight costs, particularly when post–World War I global demands sent the price of coal sky-high after 1919. Coal costs and fuel efficiency were frequent topics among Georgia railroad managers, whose company publications implored white and black employees to monitor their own coal handling.14 Furthermore, the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century coal sector was plagued with labor strikes and by poor management. For example, the coalfield wars and United Mine Workers’ organized national strikes in Pennsylvania, Colorado, and Alabama between 1890 and 1920 affected coal production, shipments, and markets.15 In this context, coal supplies, deliveries, and costs were unpredictable when workers went on strike. This volatile muscle-powered and mineral-fueled market helped New South capitalists make a choice and shift from soot-producing coal as a primary energy source to a renewable organic energy environment that eliminated some variables. The new fuel in the Southeast was the old waterpower transformed into slick hydroelectricity generated with white coal.

James B. Duke was just one of many industrial boosters who equated clean hydroelectric production with textiles and light-manufactories in the New South. J. A. Switzer, a professor of hydraulic engineering at the University of Tennessee, believed that luring industry to the New South, including “the industrial expansion already attained,” was a result of “the cheapness of water-power already developed.” And additional industrial growth—in textiles and other manufactures—would “greatly stimulate the further development of the remaining latent waterpowers” throughout the New South.16 Thorndike Saville, another engineer and booster, commented in 1924 on corporations’ total energy production and consumption in North Carolina, which, since 1912, had rapidly “surpassed its neighboring states.” Furthermore, he noted, “this output is a sensitive index of industrial development and reflects the acknowledged superiority of North Carolina in this respect.”17 Cheap organic energy clearly lured textile and other producers to the Southeast. Companies mothballed many cotton mills in New England, and “the Piedmont’s share of the total number of textile workers rose from 46 to 68 percent” between 1923 and 1933.18 The New South’s energy supply was renewable and cheap, was more easily manipulated than human labor, and was a major factor in this recentering of the American textile industry before the Great Depression. In other words, cheap renewable energy hastened the initial textile boom, and the continued industrial and energy developments paralleled each other. Maintaining cheap energy rates helped the Southeast remain competitive.

Before engineers and executives could develop all of the potential waterpower sites in the New South, they had to build privately owned and state-based systems. One hydraulic expert and booster noted in 1912 that Duke Power maintained 1,380 miles of transmission lines over a territory that “stretche[d] 200 miles from east to west and 150 miles from north to south” to deliver electricity to 156 cotton mills, homes in forty-five mill towns, municipal street lights, and an interurban railway with about 150 miles of track in North Carolina and South Carolina.19 And by 1924, 80 percent of Duke’s electricity went to textile facilities, while other factory operations (such as tobacco and furniture) consumed 10 percent and municipal systems absorbed the remaining 10 percent.20 Duke’s energy company was initially the most successful at harnessing a single southeastern river with a series of dams and artificial reservoirs placed one after the other in a series, but the institution soon faced stiff competition as other investors also raced to deploy transnational technologies, conserve New South water resources, and consolidate corporate power.

Private companies in Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina followed Duke in the complex task of environmental manipulation and energy production.21 Each individual company incorporated old and new ideas to create dam, reservoir, and transmission networks that fit site-specific environments in different watersheds. Every business assumed nature’s energy—falling water—would always generate electric power, but they all learned that rivers did not always participate willingly in conservation regimes. When water did not cooperate, corporate bottom lines were threatened, productivity on factory floors faltered, and the fate of public-private development schemes was uncertain. Rupert Vance had informed his regionalist-inspired readers that “while the greatest potential water resources of the area” could “be found in the Tennessee River system, the highest actual development ha[d] been reached on the Catawba River” by Duke’s company.22 But in contrast to the situation in North Carolina, according J. A. Switzer, “there were no hydroelectric plants in operation in the State of Tennessee” in 1905.23

In Tennessee, one river project demonstrates the environmental, institutional, and technological difficulties involved in manipulating water and generating energy on a grand scale in the New South. The Hales Bar development underscored the dangers of public-private schemes while accomplishing many engineering firsts by 1914. Hales Bar, built between 1905 and 1913 by the Tennessee River Power Company, was the nation’s “first case” where engineers combined hydroelectric generation with navigation, according to one industry periodical.24 Chattanooga boosters and businessmen had conceived of plans for a dam and navigation lock in the vicinity of their city after observing “the progress of the development of water power in various parts of the country.” The boosters then lobbied Congress and received a ninety-nine-year lease from the federal government in 1904 to complete a Tennessee River energy and navigation project that also required inspection and approval by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.25

The Corps, after all, was initially tasked by Congress with a civil works mission to improve navigation on the nation’s waterways. Army engineering units have served the U.S. military since the American Revolution, but it was not until 1802 that Congress formally established the Corps of Engineers. Between 1900 and the 1930s, the Corps’ civil works mission expanded to include flood control, but the Corps could participate in flood control projects only if the improvements enhanced navigation and benefited the national economy. Corps engineers were not oblivious to the waterpower and navigational potential of the Tennessee River valley, but the national leadership of the Corps was wary of multiple-purpose projects like Hales Bar and had not yet joined the private sector as dam builders. Until the 1930s, the Corps’ primary civil works responsibility was to grease the wheels of commerce by keeping the nation’s navigable waterways such as the Tennessee River open for boats and barges.26

Despite the Hales Bar project’s collaborative and engineering successes, this corporate attempt at a massive dam and reservoir scheme faced many environmental challenges. Industrialists succeeded in completing the multiple-purpose project, but as one Corps of Engineers historian has explained, the dam and powerhouse encountered construction tests that left the Corps responsible for navigational facilities in a structure it considered a potential liability.27 The region’s porous Bangor limestone and sedimentary rock presented engineers and workers with no shortage of problems as they attempted to set the dam’s and the powerhouse’s foundations. This limestone was apparently “soluble in the river water,” according to one technical writer, and “had a geological exploration been made, this condition would” have likely resulted in the project’s termination. But the project continued as engineers and laborers drilled hundreds of vertical holes up to fifty feet deep before pumping cement grout under pressure into the holes to fill horizontal and lateral fissures. Workers used more than 200,000 bags of cement to manufacture “solid rock” for the dam’s foundation. This solution worked in the short term, but in 1914 four “boils” emerged below the dam, indicating that water continued to enter limestone crevices in the riverbed above the dam, flow through limestone channels under the dam’s foundation, and reemerge from the riverbed immediately downstream.28 Engineers fixed isolated spots, but new boils continued to emerge on the dam’s downstream side. Between 1919 and 1921, engineers injected asphalt-grout under the dam’s foundation to depths of 130 feet. This method—apparently used elsewhere only once before—stopped the major leakage and reduced the overall number of boils, but it still could not seal all of the leaks. Seepage represented not only lost storage and potential energy. The leaking foundation also signaled that private industry was not entirely capable of financing and engineering multiple-purpose projects of this magnitude.

This limited public-private venture into multiple-purpose planning and water conservation in the Tennessee River valley did not bode well for future collaborations, since the initial projected cost of $3 million mushroomed to an actual cost of $11 million. “At the time of construction, Hales Bar was a great precedent setting project,” noted TVA engineers in 1941. Excepting some western dams and the Niagara Falls project, Hales Bar was the “largest single hydroelectric development in the South” when the complex was completed in 1914.29 But the engineering failures, from site selection to water storage problems, did not inspire future confidence in public-private conservation or power-sharing schemes. Furthermore, private corporations and their investors discovered the range of financial and environmental dangers inherent in building massive dams, navigational locks, powerhouses, and reservoirs. This realization kept some companies on the sidelines and provided ammunition for Progressives who were critical of the private energy sector’s monopolistic tendencies.

This was serious business: Tennessee hydraulic engineer J. A. Switzer understood in 1912 that it did “not require the prophetic vision of a dreamer to suppose that the day will come when practically the entire length of such rivers as the Tennessee will be linked to water wheels, and so be forced to contribute their maximum to the country’s supply of power.” Switzer continued: “Nor is it visionary to say that the next great step will then be the building of enormous reservoirs at the headwaters of the rivers to impound the flood waters now going to waste, and by means of them doubling or trebling the power susceptible to utilization at all such sites as Hale’s Bar. Just as certainly as that the Government will complete the Panama Canal will the Government in due time undertake this work.”30 The prescient Switzer envisioned not private enterprises but instead extensive government valley and headwaters projects throughout the nation, starting with the Tennessee Valley.

As the lead federal institution in the Tennessee River valley at the time, the Corps of Engineers approached multiple-purpose dams and projects with trepidation. While the Corps today manages hundreds of multiple-purpose dams and reservoirs, it amassed this responsibility very slowly, beginning in 1918 at a place downstream of Hales Bar called Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Throughout the nineteenth century, individuals and investment groups had presented the federal government with plans to improve navigation and harness Muscle Shoals’s immense waterpower potential. Before and after World War I, successive administrations were mired in conflict over how to acquire, develop, manage, and then dispose of federal property at Muscle Shoals. To clear the environmental, financial, and technical hurdles evident at Hales Bar, some Muscle Shoals promoters had suggested public-private partnerships in which the federal government would pay for navigational improvements and a large dam, while energy corporations would finance generation and transmission facilities. Hales Bar’s environmental and staggering financial challenges, however, made public-private schemes at Muscle Shoals a tough sell.31 After the Great War commenced in 1914 and the nation’s participation was imminent, Congress eventually acquired two dam sites from the Alabama Power Company and approved construction of two nitrate production facilities at Muscle Shoals and a dam to generate electricity for wartime industry. As construction proceeded, intense national debate ensued over the federal government’s entrance into the fertilizer and energy production business, and this well-documented New South battle at Muscle Shoals between big business (namely the Alabama Power Company) and Progressive reformers (led by Nebraska senator George W. Norris) influenced the ultimate shape of the liberal New Dealers’ TVA.

The debate over the fate of Muscle Shoals was an important national exercise involving many public and private participants who contributed to the TVA concept, but the creation of the TVA all too often overshadows other aspects of this earlier dispute. Understanding the pre-TVA role of private hydroelectric power illustrates what private energy corporations stood to lose during this famous dispute over Muscle Shoals, as well as why private interests continued to vilify federal hydroelectric energy projects as symbols of New Deal liberalism in the following quarter-century. As Preston J. Hubbard has concluded in his detailed analysis of the debate, Muscle Shoals occupied “an important place” in U.S. history because the conflict was essentially about who should control energy markets and conservation of the nation’s natural resources.32 It is also worth repeating that when the Corps of Engineers built Wilson Dam at Muscle Shoals, the agency was not devoted to multiple-purpose dam building or energy production. According to David P. Billington and Donald C. Jackson, the national leadership of the Corps considered multiple-purpose projects like Muscle Shoals “controversial” well into the 1920s because of a national debate about public versus private energy production and the financial costs. While the Corps’ resident Tennessee Valley engineers thought massive dams could serve many beneficial purposes, not until the 1930s did officers in Washington, D.C., recommend that Congress seriously consider federal multiple-purpose projects.33

Other Tennessee River valley energy firms and transnational corporations manipulated the state’s waterways to generate energy and consolidate economic power in the urban-industrial New South. Private corporations, including the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa), built at least twenty-one hydroelectric dams on the Tennessee River’s tributaries between 1905 and 1928.34 The Great Depression derailed all companies’ plans to fully develop southeastern rivers and disrupted private water storage and management projects throughout the New South. However, Tennessee and other energy companies were not the only organizations to deploy transnational technologies and consolidate corporate power throughout Rupert Vance’s “Piedmont crescent of industry” in the 1920s.

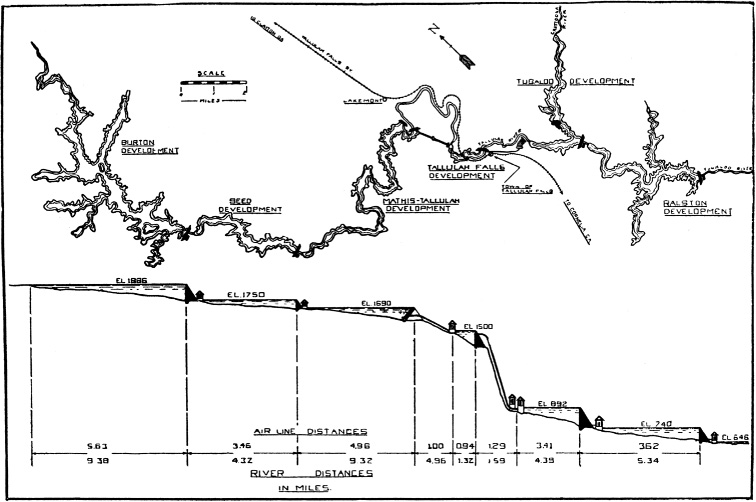

One last example illustrates the scope of corporate power and the scale of environmental manipulation in the New South before the genesis of the TVA. The Georgia Power Company’s engineers and laborers captured the Savannah River’s headwaters and transformed the Tallulah and Tugaloo Rivers into a series of artificial lakes behind multiple dams to generate electricity for transmission to faraway consumers. During the Tallulah-Tugaloo project’s formative stage in the early 1900s, one writer noted that the company planned a “vast network of interconnected hydroelectric power systems … along lines similar to those of the” Duke Power Company.35 Georgia Power’s ventures on rivers throughout the state were like other companies’ projects in Tennessee and throughout the Carolinas: Georgia Power’s schemes required external capital and transnational engineering expertise, and the company’s choices further solidified the energy-water nexus in the region.

Big dams that diverted water into long pipelines and powerhouses were not exceptional, but the scale of Georgia Power’s project was unique for the Southeast.36 Starting in 1910, Georgia Power completed six dams and filled six reservoirs along the Tallulah and Tugaloo Rivers in the upper Savannah River basin. When the company completed the last dam and reservoir project in 1927, Georgia Power’s Tallulah-Tugaloo system constituted “the most completely developed continuous stretch of river in the United States,” according to company historian Wade H. Wright.37 The corporation’s artificial reservoirs and hydroelectric plants worked together to produce electricity on demand, as one company executive claimed, for “many thousands” of industrial employees and for more than sixty-five Georgia municipalities.38 More than 800 miles of transmission lines strung throughout Georgia connected the Tallulah-Tugaloo hydraulic system’s falling water to these consumers. To see a map of this hydroelectric machine, or to see it from the air, was to peer into the future of another southeastern river valley just a few miles away on the other side of the Eastern Continental Divide. Georgia Power’s system in the Savannah basin—like other New South private utility companies—was a prototype for the New Deal’s signature modernizing tool: the TVA.

Preston S. Arkwright Sr. (1871–1946) recognized the power that he wielded as a broker of water and energy. Arkwright estimated that the Tallulah-Tugaloo integrated system directly benefited Atlanta’s citizens and the region’s textile employers, and he explicitly linked consumers to the northeast Georgia project’s water supply and electrical production. Arkwright—born in Savannah, Georgia, and perhaps a distant relative of Richard Arkwright, who invented a water-powered spinning frame in late-eighteenth-century England—declared that “electricity puts at the finger tips the force of the mountain torrents and … energy stored” for centuries.39 This energy, he continued, was “a silent and unobtrusive servant in the home—always ready, without rest, vacation, sick leave or sleep; eager for its task, tireless, day and night.” Arkwright believed hydroelectricity could “banish drudgery and bring convenience and comfort and ease and cheer and joy to human beings.” As an instrument for domestic consumers still dependent on human labor, hydroelectric energy was like having servants “on tiptoe” behind a wall waiting to spring “forth at your summons, waiting to do your bidding.” Hydroelectricity, in Arkwright’s thinking in 1924, might create a domestic and industrial labor utopia free of racial and class conflict. After the brutal 1906 Atlanta race riot left dozens of African Americans dead, and after post–World War I cuts in textile mill production and wages led white mill workers to strike between 1919 and 1920 throughout the Southeast, Arkwright was not the only person to pin the future on white coal. But Arkwright’s assumption—and that of his contemporaries in the energy, agricultural, and industrial sectors—that water resources could benefit his company’s customers and help solve the New South’s manufactured race and labor problems was more dream than reality. Transmission lines ran from dams to urban-industrial areas, skipping an intermediary agriculture zone cultivated by sharecroppers and poor farmers and leaving them without electricity for another decade or more. And textile worker strikes in Elizabethton, Tennessee, and Gastonia and Marion, North Carolina, in 1929 proved that white coal was no panacea for industries that continued to stretch and squeeze energy out of people. In the near future, the company’s other urban and industrial customers also learned how a dependence on hydraulic systems like the Tallulah-Tugaloo’s waterscape could be dangerous.

Tallulah and Tugaloo Project, 1921. In Benjamin Mortimer Hall and Max R. Hall, Third Report on the Water Powers of Georgia, Geological Survey of Georgia, Bulletin No. 38 (Atlanta: Byrd Printing Company, 1921).

When Henry Grady’s New South was hitched to white coal, falling water nearly 100 miles from Atlanta benefited urban dwellers and workers increasingly dependent on electricity and the corporate transmission system that delivered that energy. For instance, electric elevators served metropolitan low-rises and “large office buildings” as early as the 1890s, when more than 65,000 people lived in Atlanta.40 Atlanta’s streetcar companies had begun to shift from mule-drawn streetcars to electric streetcars and trolleys after 1890, hastening the development of the Georgia Power Company and new streetcar suburbs like Inman Park.41 Like most major urban areas in the late nineteenth century, Atlanta also increasingly turned away from gas-powered to electric lighting. By the early 1900s, the generation and transmission of electricity made commercial and residential consumption possible while powering ice-making, electric sewing machines, bakeries, and printing offices.42 These applications enabled entrepreneurs and boosters to enthusiastically partner electricity and industrialization with a modern New South in the pages of the Manufacturers’ Record, Electrical World, and Engineer News Record. One such cheery writer could boast that Atlanta’s approximately 235,000 residents enjoyed the “third lowest average power rate” of any city in the nation in 1924. Furthermore, Georgia Power’s interconnection with other regional energy corporations assured the city’s “industries against any interruptions in service.”43 Could all this occur in a backward region? To the contrary, Georgia Power’s access to a renewable energy source, its engineers’ incorporation of transnational technologies, and the company’s interconnected hydraulic electrical generation system linked the state’s hinterland resources and factories to Atlanta’s urban-industrial core. This modern—and inequitable—system also delivered energy to a far larger constellation of New South hinterlands and hives.

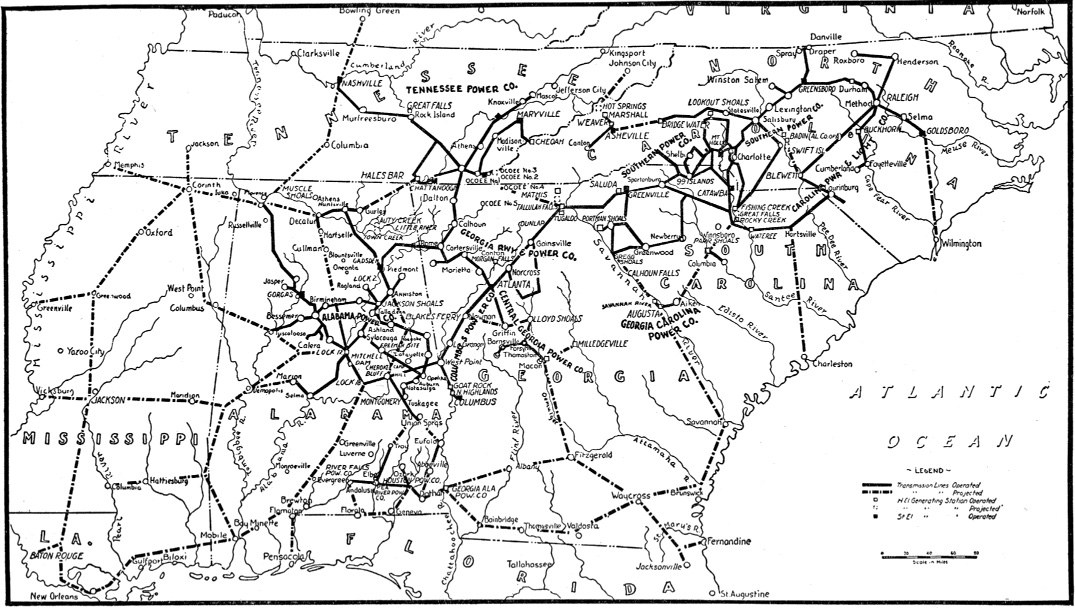

Energy companies around the country began experimenting with interconnected production facilities and transmission grids in the early decades of the twentieth century. Powerful southeastern energy corporations, however, put the most complete system into operation. Electrical engineer William S. Murray promoted one such system, called a “superpower zone,” to coordinate energy production and distribution throughout the Northeast’s metropolitan corridor and across state lines. In a 1921 U.S. Geological Survey report, Murray asserted that a coordinated and privately managed energy grid could facilitate technological standardization and assure reliable service. Northeastern energy executives, however, were reluctant to participate in electrical interconnections in their region.44 In stark contrast, the major southeastern energy companies—Alabama Power, Georgia Power, Duke Power, and Tennessee Power—did not share this reluctance. In an example of extraordinary business acumen, these independent companies began interconnecting in 1912 and assembled a fully connected Super Power grid by 1921. According to utility trade journal editors and water professionals such as Thorndike Saville, the New South’s pre-1930 Super Power system was “unparalleled in the world” and represented “a more complete integration of power-producing and transmission capacity” than any other system on the planet.45

Production and distribution interconnections were not uncommon in the United States and Canada, but the southeastern system’s scale and scope were remarkable. Private energy executives enlarged, and engineers consciously built Super Power during the roaring 1920s by way of corporate consolidation. In 1924 the Southeastern Power and Light holding company reorganized the Alabama Power Company and other utilities, including two firms that subsequently made up the Georgia Power Company at its founding. Then in 1929, the New-York-City-based Commonwealth and Southern Corporation assumed a 40 percent ownership of the Southeastern Power and Light and all of its subsidiaries, including Alabama Power and Georgia Power.46 Duke Power Company also consolidated smaller energy utilities in North Carolina and South Carolina but was never financially tied to larger regional or national utility holding companies.47

Super Power—or what Vance in 1932 defined as a hydroelectric complex—was a lot like another complex that tied regions together. Super Power proponents, such as Alabama Power Company president Thomas Martin, defended these massive corporate linkages and the electrical production infrastructure by equating Super Power with the railroad systems that moved people “across the continent without change of cars,” and he likened individual energy companies to independent railroads that shared standardized railroad tracks and equipment. Each energy company, Martin argued, was “independent, assumes a duty to its own customers, provides its own management, adopts and pursues its own policies, attends to its own financial affairs and is subject to the authority where it operates as to rates and service and security issues. The component companies merely draw from and contribute surplus energy to others which otherwise would go to waste and benefit no one.”48 By 1924, the well-organized southeastern interconnected grid relayed electrical power over 3,000 miles of high-voltage transmission lines and served 6 million people in a 120,000-square-mile region encompassing a half-dozen states.49

Critics condemned the early interconnections and the vast Super Power network. These networks, in the words of historian Sarah T. Phillips, consolidated “power—electric power, manufacturing power, economic power” in urban-industrial centers at the expense of rural consumers and citizens.50 Progressives and liberal reformers shifted their criticism from railroads to electrical utilities, since the new enemy, like the former one, was a natural monopoly. Customers were compelled to purchase services from a single unregulated provider that faced no market competitors. Industrial proponents considered these energy companies and utilities natural monopolies because competitors recognized there was no economic incentive to duplicate service and capital-intensive infrastructure in the same market territories. A congressionally approved 1916 study by the Department of Agriculture, as well as others that followed, confirmed many critics’ early claims.51 Based on a comprehensive study of the nation’s public and private electric generation installations and ownership patterns, the report concluded, “There are several lines of evidence which show a continuously increasing tendency toward concentration in the control of the development, distribution, and sale of electric power. Each year shows a greater percentage of electric power being produced by” privately owned entities. The report illustrated that distinct regions were under the control of companies like Duke Power and Carolina Power and Light (the two companies were responsible for generating and distributing 66 percent of all electricity in North Carolina).52 Progressive and social reformers criticized state agencies and fledgling public utility commissions for allowing corporate consolidation to accelerate in the 1920s. The individual energy companies may have operated independently, as Thomas Martin of Alabama Power claimed, but the interconnected electrical grids looked a lot like Stephen J. Gould’s railroad empire and bore a striking resemblance to Udo J. Keppler’s Standard Oil octopus. Indeed, in 1913 the editors of the Southern Farming periodical superimposed a “Water Power Trust” octopus over a map of the United States and offered a rallying cry: “Do not let the New Octopus Monopolize the inexhaustible supply of white coal in our Southern States.”53 Super Power visionary William S. Murray surely stoked agrarian, populist, and Progressive rage when he observed that “electricity is the True Agent of Power” and “no business ever succeeded without good agents.” Southeastern energy companies, however, took this model to heart.54

Not to be outdone, Progressive reformers offered an alternative to Super Power as business structures evolved in other American regions. Pennsylvania governor Gifford Pinchot and Morris L. Cooke were among the most visible proponents of so-called Giant Power. This idea emerged in 1924 as a public power program that could check corporate greed and monopolistic utilities, reduce electrical rates, electrify rural areas, and promote conservation of natural and energy resources. The program envisioned publicly owned coal-fired electrical generation plants in coal mining areas and high-tension transmission lines that would link the mouth-of-mine thermoelectric steam plants with rural and urban customers. As originally conceived, Giant Power went down in flames, derided as a communist fantasy.55 While Giant Power never fully materialized, its liberal backers did eventually influence New Deal initiatives such as the Rural Electrical Administration (REA) and TVA. Until that time in the New South, large energy corporations and natural monopolies used Super Power and its good agents to build a southeastern urban-industrial region.

Alabama and Georgia energy companies exported a high percentage of excess electricity via the New South Super Power system to the Carolinas, where regional textile mill growth and electrification were greatest in the early years of the twentieth century, thanks in part to James B. Duke’s industrial subsidies and incentives that cultivated industrial customers. Because of the region’s Super Power transmission and distribution geography, Atlanta became “the chief city on this system and a center of utility activity” by 1928, according to hydroelectric booster L. W. W. Morrow.56 The Georgia Power Company occupied the center of this vast hydraulic system and linked an elaborate hydraulic hinterland that stretched across Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Tennessee.57

Environmental conditions in Georgia and North Carolina soon tested the system and the individual energy companies. This Super Power grid did more than connect multiple states and a half-dozen different energy companies capable of producing more than 1 million horsepower. These interconnections also provided more than a means to transport surplus electricity: They functioned as lifelines. The interconnected systems quickly justified themselves when region-specific droughts struck the New South and significantly reduced hydroelectric generation between 1921 and 1925.58 In response to the drought, the water-dependent energy companies used the Super Power grid to manage river flows in “separate and distinct water sheds.”59 Water conserved and run through turbines in one state’s watershed produced energy that could be transferred over high-tension transmission lines across another state to facilitate energy delivery to yet a third state hundreds of miles away. This was Super Power in action.

The late summer drought of 1925 led to “one of the greatest power shortages in the history” of the American South, according to the Atlanta Constitution.60 Droughts had previously affected cities and towns like Atlanta and Augusta, where textile mills sitting on riverbanks and dependent upon local river flows frequently ceased production as water levels exceeded or dropped below operable levels.61 For example, the Savannah River’s water flow itself had dropped precariously in 1918 and threatened “a general close down” of industrial and commercial operations in Augusta because the Stevens Creek hydroelectric dam and other small plants along the Augusta Canal could not generate enough energy to keep factories running and workers employed.62 But the option of shutting down twentieth-century businesses or not providing expectant customers in a major metropolitan area with reliable electrical or streetcar service was unsustainable for corporations with significant capital investments. Geographically isolated nineteenth-century outages only threatened individual urban-industrial nodes, but the droughts and rolling “blackouts” of the 1920s presented a broader problem requiring a shift in corporate strategy.63

At the time of the 1925 drought crisis, Georgia Power executives declared that a mere four weeks’ supply of water remained in the Tallulah-Tugaloo project’s “giant hydro-electric reservoirs” of northeast Georgia. Despite claims from company officials in 1920 that such dams could conserve water supply through “the severest drought,” the 1920s circumstances presented the grim reality of an energy-water nexus choke point.64 While generating every possible kilowatt of energy from the company’s operable hydro facilities and auxiliary coal plants, Georgia Power in 1925 imported “hundreds of tons of coal … to meet any emergency which might be caused” if operations exhausted the limited remaining supply of renewable energy. Georgia officials also discussed the situation with executives from “textile mills, brick, marble, granite mining and other industries,” and the corporate customers agreed to limit their energy use “as much as possible and to operate at nights” for the duration of the drought-induced “crisis.”65 Atlanta’s consumers also agreed to follow restrictions in place between August 21 and September 7, and full streetcar service did not resume for another month.66

Super Power Transmission Network, 1924. In Blue Book of Southern Progress, 1924 ed. (Baltimore: Manufacturers’ Record, 1924). Courtesy of Conway Data, Inc.

When Atlanta producers and consumers faced this crisis, the interconnected Super Power transmission network ultimately averted more draconian orders. “To the relief of Georgia industries,” the state’s energy companies imported electricity produced in Alabama and Tennessee in August 1925.67 The federal government sold energy generated in the Sheffield coal-fired steam plant and from the newly operational Wilson Dam (Muscle Shoals) to the Tennessee Electric and Power Company and the Alabama Power Company, who in turn transferred the energy—some of which could be classified as “coal by wire”—to Georgia and the Carolinas.68 The droughts of the 1920s threatened New South water conservation and consumption plans, but the Super Power grid enabled electricity to move seamlessly from one state to another. This technological network linked wet hinterlands and cores with drier neighbors and thus allowed energy-dependent consumers to avoid thinking too hard about the energy sources and infrastructure that sustained the modern New South. The Super Power grid integrated the region but had not integrated the region into the nation, as railroads had done elsewhere and as regionalists like Vance had hoped would happen. Instead, the Southeast became a new destination for factories and businesses hungry for cheap natural energy, liberal tax incentives, and tractable human labor. During the 1925 drought, energy companies learned the hard way for the first time that southern rivers, not unlike mill workers, could, in fact, go on strike.

The droughts of the 1920s not only highlighted the utility of interconnected grids; they also revealed a water supply problem, the limits of hydropower, and a technological plateau. James B. Duke and other energy company executives had championed white coal as a solution to southeastern economic development and energy independence, but after the 1925 drought, Duke no longer accepted hydroelectric dams as the energy-generating standard.69 Both Georgia Power’s and Duke Power’s hydroelectric expectations and risk management shifted radically in the following years, particularly as black-coal-fueled steam technology became an increasingly efficient and economical method for generating base loads. Despite continued investment in hydroelectric dams to produce peak power when consumer demands exceeded base load supply, the 1925 southeastern drought led the companies on a technological path from a hydro plateau back to coal-fired steam generation plants. The shift away from renewable energy to fossil fuels as the primary energy source might look like an abrupt about-face, but when the companies transitioned back to coal, they never distanced themselves from southeastern rivers or existing artificial reservoirs. Energy producers stopped relying on water falling on turbines to produce energy and turned instead to burning coal and transforming liquid water into pressurized steam to spin turbines. Throughout the remainder of the twentieth century, southeastern energy companies—specifically Duke Power—built coal-fired and nuclear power plants on the shores of the same reservoirs engineers originally built to conserve water for hydroelectric generation, and the companies also built some new reservoirs for new coal-fired plants.70 Furthermore, after the 1925 drought, Georgia Power’s chief executive abandoned plans to build new hydroelectric white coal projects on north Georgia’s Chattooga and Coosawattee Rivers and instead invested in black coal plants on the Chattahoochee River upstream of metro Atlanta and on the Ocmulgee River near Macon.71 White coal was no longer the industry standard, but water supplies remained critical for black coal electrical generation facilities.

The droughts of the 1920s also forced engineers to think differently about water supply. Engineers who maintained the elaborate hydraulic systems increasingly learned how to conserve and utilize water to maximize their companies’ profits while also protecting expensive infrastructure. After nearly twenty-five years of managing dams, artificial reservoirs, and auxiliary coal-fired steam plants along the Catawba River, Duke Power employees understood that “the principal problem is to operate” the combination of storage reservoirs and run-of-river hydroelectric “plants in connection with the steam plants so as to secure the maximum kilowatt-hour output from the available river flow.” The region’s climate and rivers’ behavior made it clear that not only was there great “variation in river flow from wet to dry season,” but there was “also a considerable variation from year to year,” making “it very difficult to map out” energy production schedules and “secure the maximum output from the hydro plants.” In other words, weather and consumer behavior were unpredictable. Playing the seasonal calendar, Duke employees typically filled artificial reservoirs during the wet season (January through May), kept them partially filled between May and September because summer or tropical storms could produce flooding during this time of year, and then drew the reservoirs down during the dry months between September and January.72 On average, the lowest period of rainfall occurred in the late summer and fall, but “even this phase has no regularity,” engineers observed. Evidence illustrated that North Carolina’s early 1920s droughts were followed by “exceptionally heavy precipitation” and “one of the greatest floods” in the Catawba River’s recorded history in the late 1920s.73 The private power company executives and engineers learned how fickle New South rivers straitjacketed with multiple dams had become by 1930. Water managers had almost fully engineered and controlled the region’s rivers and thus white coal and energy production without major disruption. But the companies’ success also pointed to a new southern problem and to a pre-TVA New South that was anything but exceptional. The region—a humid place assumed to have plenty of rain—also had a water problem that required water resource management and engineering on a scale once only associated with water-poor regions like the arid American West.74

Corporations financed interconnected hydraulic systems stretching from the Carolinas to Florida and across Georgia to Mississippi, and they changed the New South’s rivers and economy in the process. The New South’s private Super Power energy system and liberal Giant Power alternative also influenced the shape and character of the region’s well-documented New Deal water management institution: the TVA. Engineers from the Corps and other federal entities could look across the New South at a vast privately organized and financed electricity generation and distribution system that was more than three decades old when the TVA emerged in 1933 as a high-modernist solution for regional economic, social, and environmental problems.

Once engineers from the TVA and Corps embarked on their own New Deal–style hydroelectric projects in the 1930s, they solicited advice from academic experts, company executives, and professional engineers.75 Rupert Vance was one of those advisors. On the eve of the TVA’s creation, Vance continued to promote hydroelectric possibilities in the region while also acknowledging the inherent dangers of relying on a renewable energy source to sustain urban-industrial development. Vance had identified water as a primary energy source to fuel economic engines, but he was not ready to fully accept the prospect of water scarcity or the “Piedmont crescent of industry’s” shift to coal after 1925. In 1935, three years after Vance published Human Geography, he collaborated on a study of the Catawba River valley for the TVA. In one of the study’s appendices, titled “The Consumption of Coal in Relation to the Development of Hydroelectric Power in the Carolinas,” Vance concluded that “the Carolinas had to develop hydro power or nothing” because “cheap power attracts industries.” Vance acknowledged that a “tremendous consumption of coal in 1927” reflected Duke Power’s response to “a drought which affected” river flows and thus hydroelectric production in what his coauthors called the Catawba River valley’s “hydro-industrial empire.”76

The southeastern physiographic environment—which was fossil-fuel poor but rich in renewable energy like water—had presented Vance’s urban-industrial contemporaries with limited tools to make the New South bloom and glow. Vance, however, still believed in hydropower ten years after the Southeast’s worst drought underscored regional water insecurity. In Human Geography, Vance advised TVA technocrats to build one of the nation’s only regional planning experiments, and that they employ large hydroelectric dams as primary energy generators. But at the same time, New South energy companies had turned to black coal to generate the majority of their customers’ electricity. TVA directors and progressive engineers, however, had been so clearly influenced by a legacy of New South white coal projects that they initially embarked on a federally subsidized program that was behind a technological curve from the beginning. Private energy companies never abandoned their old hydroelectric facilities or stopped building new ones, but renewable hydro sources increasingly functioned as secondary or peak power sources. Operators could bring hydro facilities online immediately during moments of high energy demand while capital-intensive facilities used coal and other fossil fuels at a steady clip to generate primary, or base, loads. Only after World War II did the TVA once again follow private companies’ technological lead and begin building coal and nuclear plants to keep up with the New South’s fast-growing industrial, commercial, and residential consumer demands.

William Church Whitner, James B. Duke, and Preston Arkwright each understood that water-generated electricity in the Southeast was, as William S. Murray claimed in 1922, an “Agent of Power.”77 The Super Power grid as developed in the Southeast made this clear. The electrical production and distribution grid supported a regional corporate power structure that was at least as influential as individual states, politicians, planters, and industrialists, and the hydraulic system facilitated the concentration of capital and labor in specific places. The individual energy companies and their transnational employees did not rule an exceptional empire, but they did build a remarkable region defined by radial transmission lines that provided individual companies with a service and product that became indispensable in business operations and daily life. In the process, corporate power and technology wove energy production and water supply into a structure largely invisible to laborers and consumers who lost sight of the energy and water connection after the 1930s.

Unless there was a problem, early-twentieth-century consumers expressed indifference toward questions of where their energy and water came from. And professional, service, and industrial workers took advantage of electric streetcars, elevators in skyscrapers, electric fans, and electrified machinery.78 The New South’s new environmental conditions—artificial reservoirs and urban drought—had reached a point where diminished water supplies threatened daily industrial and commercial functions in metropolitan settings. Urban drought years not unlike 1925 emerged frequently throughout the twentieth century, and they continued to shape private and public energy regimes in the American South well after 1945. Rivers and falling water were significant instruments for New South developers and conservationists who used the hydraulic waterscape to concentrate labor for the benefit of the textile and other industries. These utilitarian boosters and energy sector leaders consistently transformed tumbling waterfalls into waterwheels, rocky shoals where migratory fish spawned into turbines, and free-flowing rivers into “slack-water,” artificial reservoirs plied by recreational pleasure craft.79 Dam-crazy private energy company executives and engineers thought they had tamed southeastern rivers and solved regional water problems while cultivating a new modern urban-industrial landscape linked by Super Power transmission lines. Southern rivers, however, displayed a persistent capacity to function by their own rules, to trump the romantic beauty of waterfalls and the efficiency of corporate turbines with an unwelcome reality of dry riverbeds and raging floods. Southern water and southern power were hardly secure.