Chapter 7: Taken and Delivered

The Chattooga River

Water is a prime factor in most outdoor recreation activities…. Recreation on the water is increasing.

—Outdoor Recreation for America (1962)

After nearly fifty fires burned across northeast Georgia’s mountains on a single weekend in 1976, National Forest Service supervisor Patrick Thomas tried to make sense of the 800 smoldering acres of Rabun County’s public land. With more forest burned in the first two months of 1976 than in the previous two years combined, Thomas linked the recent “fire style protest” to the 1974 creation of the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River. Thomas also empathized with the group of local mountain residents allegedly responsible for the fires, noting, “I would think it was a hardship, someone taking away access to a place I’d always been able to take pleasure in.” Thomas did not explicitly identify the “someone” who benefited from the Chattooga River’s new identity, but his comment communicated that the process was not entirely equitable or welcomed by those living in the Savannah River valley’s extreme upper reaches.1 The fires did make clear how federal implementation of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968—a new watershed management strategy—stirred community protest and class conflict in the southern Appalachian mountains. This episode illustrates how one solution for the Sun Belt’s evolving water problems signaled a change for old corporate and federal powers, empowered new grassroots environmental organizations, and invited “Retro Frontiersmen” to spark fire on the land in response.

The Chattooga River—James Dickey’s famous Deliverance river—brings the Southeast’s nearly century-long water and energy history full-circle. The Chattooga is unlike virtually all other southern Appalachian rivers within a fifty-mile radius: It escaped the lumber cribs, concrete, spillways, turbines, generators, transmission lines, and reservoirs’ drowning waters found in nearby watersheds such as the Tallulah-Tugaloo. New South executives and New Deal regional planners had also identified the river as a waterpower and hydroelectric energy source for decades. Anglers, day-trippers, and canoeists had regarded the Chattooga River as a unique and endangered river for decades, complete with swimming holes, breathtaking scenery, superior trout fishing, and white-knuckle rapids. This history was immediately relevant after Congress enacted the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (1968) and directed the U.S. Forest Service to evaluate rivers worthy of protection across the country—including the Chattooga as one of the American South’s only representatives—for inclusion in this new federal land protection category.2 Forest Service staff discovered tremendous support for a protected Appalachian river among local county governments, state agencies, and a segment of the Georgia and South Carolina public. Furthermore, environmentalists who participated in the Chattooga National Wild and Scenic River campaign joined a national movement dedicated to solving water problems in the 1960s. Given this wide spectrum of enthusiasm, the Chattooga easily moved from a study river in 1968 to an official wild and scenic river in six quick years. The undammed river represented a scarce commodity for these interest groups, and thus they considered the Chattooga an extremely valuable chunk of southern wilderness worthy of federal protection.

This victory was surprising. The Chattooga River was not saved exclusively by crusading preservationists or wilderness advocates, such as those who successfully fought the Bureau of Reclamation’s Echo Park dam project (Green River, Colo.) in the 1950s.3 Instead, nearly every party involved in the Chattooga’s case—multiple federal and state agencies, new environmental groups, and many county residents—agreed that Congress should confer wild and scenic river status on the river. The process was made much easier when the traditional enemies—private utilities and federal agencies intent on building hydroelectric dams—intentionally avoided a fight during a national energy transition. A victory for one set of players rang hollow for others, as demonstrated by the burning forest. Everyone may have agreed the Chattooga River was a scarce and valuable resource, but not everyone agreed with how the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River should be used. And most people acknowledged that the valley, after centuries of land use and habitation, was no wilderness. Based on arson events and Patrick Thomas’s observations, one might assume that top-down conservation rangers remapped the Chattooga River’s watershed and resources without local input or consent.

Resistance—including clandestine acts of arson and vandalism or formal community and labor organization—has been linked to transitions in land and resource use, ownership, and management throughout the United States.4 Thus, in the Chattooga’s case, arson might look like a local anti-statist protest in response to the taking of private land or the disruption of local subsistence economies. However, the story behind the northeast Georgia fires was much more complicated than a monolithic-state power narrative. The fires set within and around this southern Appalachian river’s narrow corridor were the consequence of turning a site of local leisure along the Chattooga River into a national destination popularized by the 1972 screen adaptation of James Dickey’s novel Deliverance and protected by the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 1974. The fires, like historic acts of resistance, did not occur during the negotiation and designation process to preserve a special environment, nor were they the result of declarations of eminent domain. While the Chattooga had always represented a leisure commons for many people, the reluctance of old river users to adhere to new federal management policies—plus the crush of Sun Belt visitors stimulated by Hollywood’s visual representation of the Chattooga’s wild landscape and rapids in Deliverance—sparked a violent response during a management stage that was not nearly as smooth as the designation phase.

The Chattooga River’s story illustrates how landscape transformations, social relations, and energy choices were bound together with the Southeast’s hydraulic waterscape. First, national citizen action and engagement in water politics had ramifications for how people thought about and interacted with wild rivers like the Chattooga. For example, river advocates argued that free-flowing rivers had ecological and economic values that benefited local environments and service economies. Second, the nation’s electrical utilities continued to shift away from hydroelectricity to coal while also experimenting with emerging civilian nuclear technologies. The new fossil fuel and mineral energy sources still depended on water, but not always directly on dams, to generate base loads. Whereas the Georgia Power Company had built a hydraulic system that expropriated energy from the adjacent Tallulah and Tugaloo Rivers in the 1920s, the company delivered the Chattooga River to the environmental and paddling community for safekeeping in the 1960s. Not all of the Sun Belt’s water problems could be solved so easily, but the Chattooga River’s history illustrates how water and power continued to cycle in the Southeast with important consequences for Sun Belt rivers and communities.

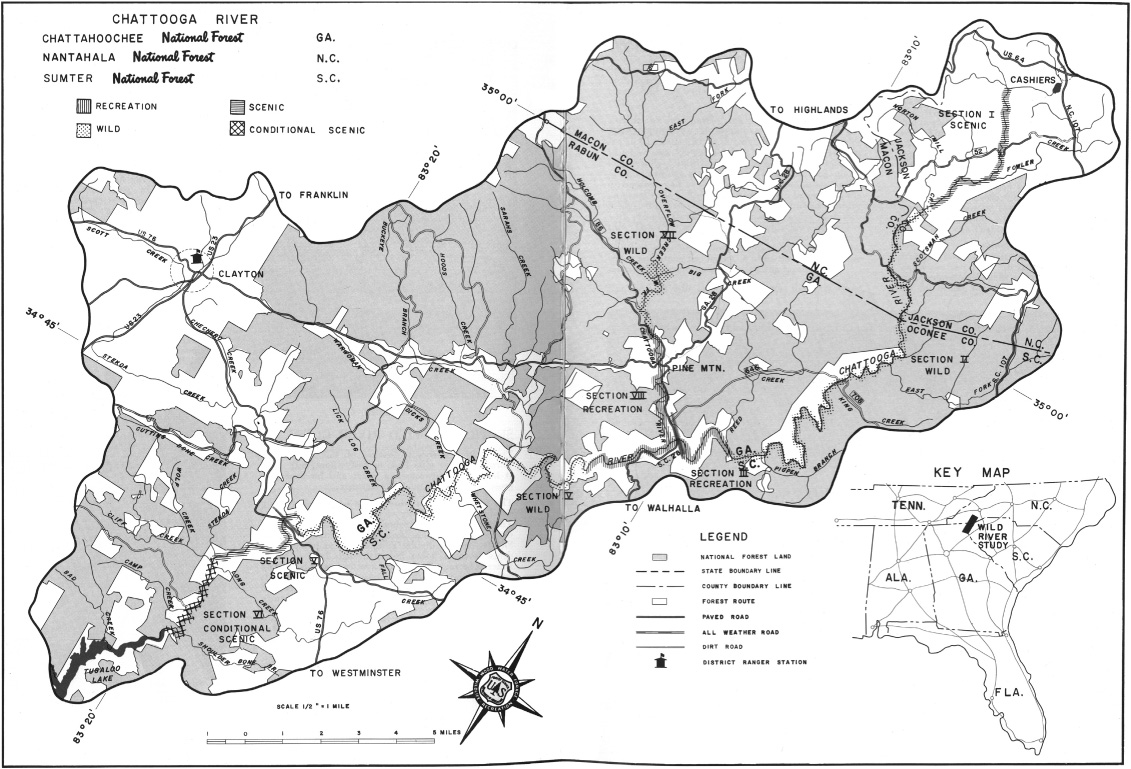

Chattooga River (Study River Proposal), 1970, including designated wild, scenic, and recreational sections. The Chattooga River’s headwaters can be located in the upper right corner of the map (below Cashiers, N.C.), and the river flows to the map’s lower left corner (Tugaloo Lake) along the Georgia and South Carolina border. In Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture, A Proposal: The Chattooga, “A Wild and Scenic River” (March 3, 1970). Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries, Athens.

Private energy corporations and federal agencies built large dam projects in every cardinal direction and every southern Appalachian watershed neighboring the Chattooga’s before 1970. The Chattooga River tumbles from the Eastern Continental Divide and the base of Whitesides Mountain’s 700-foot granite rock face near Cashiers, North Carolina. The river’s tributaries drain an 180,000-acre watershed ringed by mountains that reach nearly 5,000 feet above sea level and can receive over eighty inches of annual precipitation. (The Pacific Northwest is the only other area in the lower forty-eight states that receives this much precipitation.) The majority of the river forms about forty miles of the South Carolina and Georgia border. The Chattooga flows between the two national forests, crashing over boulders and ledges before the current slacks and fills the Georgia Power Company’s Lake Tugaloo—an uninspiring, flatwater reservoir behind a hydroelectric dam that fills the former Tugaloo river valley—one of many short stops on a 300-plus-mile journey to the Atlantic Ocean via the Savannah River.

A bird’s-eye view of the southern Appalachian headwaters clearly illustrates how the Chattooga River differs from other Blue Ridge watersheds. To the south and west, the Georgia Power Company effectively transformed the Tallulah and Tugaloo Rivers into one large water-storage pond between 1913 and 1927 to supply Atlanta with electricity to power a New South. On the west and north, the headwaters of the Tennessee River feed the Gulf of Mexico on the other side of the Eastern Continental Divide. There, Alcoa, the Tennessee Electric Power Company, and other New South energy corporations dammed the Tennessee River system’s southern Appalachian tributaries—the Tuckasegee, Nantahala, Little Tennessee, and Hiwassee Rivers—extensively before 1930. The more well-known Tennessee Valley Authority assumed control of that river and tributaries after 1933 and initiated a comprehensive plan to build more than twenty multiple-purpose dams to provide agricultural, navigational, flood control, and hydroelectric benefits for purportedly democratic and decentralized economic development in one area of a larger region labeled the “nation’s no. 1 economic problem” by New Dealers.5

Turning east from the bird’s-eye vantage point back to the Savannah River’s headwaters, Duke Power Company began building Sun Belt hydroelectric dams in Appalachian valleys to create Lakes Jocassee and Keowee by drowning South Carolina’s Whitewater, Toxaway, and Keowee Rivers in the late 1960s. To the south, and farther down the Savannah River valley itself, the Corps’ three massive hydroelectric installations appear. Engineers built these Sun Belt projects above the river’s fall line between 1945 and 1985. In contrast to these adjacent watersheds, the fifty-mile Chattooga River flowed wild and free as an anomaly, undeveloped by corporate or federal energy institutions. The Chattooga remained a river surrounded by a sea of reservoirs.

The Chattooga may have been alone in the Southeast, but wild rivers across the country were equally threatened by agricultural and energy interests. Environmental historians have long considered the battles over Hells Canyon and Echo Park as critical national battlegrounds. At both locations—in Idaho and in Colorado (see Chapter 5)—the Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation planned large multiple-purpose dams for the Snake River and the Green River in the 1950s. Organized protest that defeated both projects contributed to the rise of postwar environmentalism, and the skills opponents marshaled “carried over into subsequent wilderness and water controversies,” according to Mark Harvey.6

The wild and scenic river system was one such example. In the late 1950s, brothers John C. and Frank E. Craighead Jr. formalized a river classification system that directly influenced the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (1968). They were avid outdoorsmen, naturalists, and wildlife biologists best known for their lengthy grizzly bear study in Yellowstone National Park in the 1960s. But their personal experiences also connected these two scientists with rivers. They spent much of their childhood playing and fishing in the eastern Potomac River and their adult lives in Wyoming’s Snake River valley. The brothers also developed an intimate knowledge of the American West’s waterways, and the Craigheads acted as they watched the nation’s rivers deteriorate after 1945.7

At the same moment that the Craigheads spoke for wild rivers, members of Congress linked water quality and scarcity with national economic development in the 1950s. John Craighead spoke before the traveling Senate Select Committee on National Water Resources that toured twenty-four American cities and towns to hear about water pollution in 1959. John leaned heavily on evolving ecological systems theory when he characterized watersheds as “both ecological and economic entities” where the whole was “equal to more than the sum of its parts.”8 John believed that those best equipped to identify rivers in need of protection were people like himself and others at “the grass roots.”9 In individual statements before the Senate Select Committee, in National Geographic publications, and in academic articles, the Craighead brothers made the case that free-flowing rivers had to be protected for educational and recreational purposes and to maintain a clean and healthy water supply.10 Combined, these conditions would stimulate an outdoor recreation economy that could tap the 44 percent of Americans who preferred “water-based recreation activities over any others.”11 In short, congressionally designated wild and scenic rivers like the Chattooga could help solve the nation’s wide-ranging water problems.

Beginning in the late 1950s the Craigheads helped develop and write an equivalent to the Wilderness Act (1964) for the nation’s undeveloped rivers, since the legislation had intentionally excluded rivers. John stated in an interview with river historian Tim Palmer that he “had worked on the wilderness legislation with Olaus Murie, Howard Zahniser, Stewart Brandborg, and others … but they were not interested in rivers” and were more focused on wilderness areas that lacked “rivers because the lands were at high altitudes.” The more he became involved, John continued, “the clearer it became that we needed a national river preservation system based on the wilderness system but separate from it.” So the Craigheads joined forces with Sigurd Olson (Wilderness Society), Joe Penfold (Izaak Walton League), Bud Jordahl (a close colleague of the late senator Gaylord Nelson), and Leonard Hall (Missouri journalist), and together they bent the bureaucratic ears of Ted Swem (National Park Service) and Ted Schad (staff director, Senate Select Committee on National Water Resources).12 Collectively, these river enthusiasts, recreation professionals, and water experts drafted the first wild and scenic rivers act, which was a component of President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s Special Message to the Congress on Conservation and Restoration of Natural Beauty. In retrospect, the president’s February 1965 message was a quaint start for a Congress that would address water pollution, watch riots engulf cities, expand civil rights via the Voting Rights Act, and face public opposition to an escalating conflict in Vietnam.13 Nonetheless, by 1968, congressional members approved legislation and created the National Wild and Scenic River System. The act immediately protected eight rivers (and four tributaries); slated twenty-seven as “study rivers,” including the Chattooga; and requested reports describing the characteristics that made study rivers worthy of designation.14 The Craigheads had successfully shepherded a new land management designation through Congress to benefit the nation’s rivers and those intent on solving water problems.

While wild and scenic river proponents like the Craigheads worked with Senate colleagues in the early 1960s to produce the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the U.S. Department of the Interior announced a national “Wild River Study” of twelve rivers. In 1964, Interior staff tasked the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service with executing an investigation that included the Savannah River’s Georgia and South Carolina tributaries.15 Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall was well aware of the Corps’ plans for hydroelectric dams in Sun Belt river valleys, and of Duke Power’s specific proposal to build Lakes Jocassee and Toxaway plus the adjacent Oconee nuclear power station.16 Udall “strongly” believed “that at least one major tributary of the Savannah River—the Chattooga—should be preserved in its free-flowing condition for the benefit of future generations and for the purpose of giving needed balance to the comprehensive development of this river.”17 At this juncture in 1965, the Department of the Interior went on record and recommended that any corporate or federal agency seeking approval to build any dam in the Chattooga River valley be denied a Federal Power Commission license. But Udall and the Department of the Interior were not the only ones interested in protecting the Chattooga in the 1960s.

Georgians and South Carolinians joined the initiative as Udall promoted a national wild rivers study group. Jack Brown, the Mountain Rest (S.C.) postmaster, wrote Congressmen W. J. Bryan Dorn (D) claiming that he was “born and raised here near the Chattooga River” and that he thought a fully designated wild and scenic river would be good for the region. Brown expressed a keen interest in how “tourist potential” might be developed. But he supported Forest Service acquisition of additional land only if such land was necessary for “something like the National Wild River System which I understand will preserve and develope [sic]” the property for recreation. Brown’s correspondence exposed his opinion that the National Forest Service’s general land management process could limit timber cutting, and thus forestry-related jobs, but the wild and scenic river idea seemed to balance recreational jobs and preservation.18 Other conservationists such as Ramone Eaton also acted on behalf of the Chattooga’s watershed. Eaton—a pioneer in southeastern boating culture, a former Atlanta educator, and then an American Red Cross executive in Washington, D.C.—reminded Greenville, S.C., attorney C. Thomas Wyche in 1967, “You may remember that the Toxaway Gorge area was lost to the Duke Power [Company’s dams and reservoirs] because of the complete indifference of the South Carolina citizenry.”19 Wyche also encouraged Congressman Dorn and counterpart Senator Ernest F. Hollings (D) to support inclusion of the Chattooga in the 1968 Wild and Scenic Rivers Act because, he feared, “too often South Carolina does not have a voice in matters of this sort simply because there is no organized group in this area that has any interest in such things and we let matters of this sort go by default.”20 Brown, Eaton, and Wyche recognized that the Chattooga, unlike the downstream Savannah River, where two hydroelectric dams had come online between 1954 and 1962, could remain wild and dam-free. The unimproved Chattooga’s scenic attributes, exemplary whitewater, and lack of development perfectly fit the specifications of the national wild, scenic, and recreational rivers policy promoted by the Craighead brothers in the 1950s.

The Chattooga River’s 1968 designation as a study river fits well within the larger national process that produced the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. River advocate Tim Palmer has written extensively about the U.S. river and conservation movement and how national dam planning and construction initiated in the 1920s slowed during the Great Depression only to resume with intensity in the 1950s. These public water development programs typically placed secondary emphasis on recreation, water quality, and the free-flowing rivers Eaton and Wyche valued. The existing wild and scenic river narrative also follows wilderness crusaders who were against dams and “for a river,” as the famous environmentalist and former Sierra Club executive David Brower once said.21 In this contest, the Chattooga’s story closely paralleled the nation’s other wild and scenic river stories. Many Sun Belt countryside conservationists and environmentalists organized and challenged river development at places like Trotters Shoals on the Savannah, in North Carolina’s upper French Broad River valley, and along the New River in southwestern Virginia. They all spoke on behalf of “their” river or rallied to protect unique landscapes. Sun Belt Georgians and South Carolinians who spoke for the Chattooga River in the 1960s and 1970s had much in common with other countryside conservationists and environmentalists in their own regions and around the country.

In Georgia, two institutions established in the 1960s reveal how Sun Belt residents cultivated cooperative relationships with corporate and federal agents to reshape the balance of water and power. These countryside conservationists utilized state agencies, grassroots initiatives, and scientific expertise to speak for a wild and scenic Chattooga River. The Georgia General Assembly established the first institution—the Georgia Natural Areas Council—in 1966 to survey the state’s rare and valuable plant and animal species, “or any other natural features of outstanding scenic or geological value.”22 Georgia State University ecologist and trout fisherman Dr. Charles Wharton drafted the council’s founding legislation, which freshman state senator and future governor Zell Miller introduced.23 The council, composed of eight members selected from four state agencies and four Georgia institutions of higher learning, possessed no explicit regulatory or direct management authority over natural resources and served primarily in an advisory capacity to the state. Robert Hanie, the council’s first executive director and a recipient of multiple Emory University degrees, collaborated with state resource managers and university scientists like Wharton and Eugene P. Odum to make recommendations on what “natural areas” the state should consider protecting. Hanie maintained a skeleton staff of volunteers and academic scientists who also developed policy and legislative tools such as the Georgia Scenic Rivers Act (1969).24

If the Georgia Natural Areas Council championed the Chattooga River as a prime example of a state natural area worthy of protection, a second institution, the Georgia Conservancy, molded opinion on behalf of the river as an irreplaceable national resource. The Georgia Conservancy played an important role as a mechanism for change during the Chattooga’s wild and scenic river study phase and campaign. James A. Mackay—a former City of Decatur legislator and member of Congress—served as the founding president for the Atlanta-based nonprofit Georgia Conservancy in 1967, an organization modeled after the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (established in 1932) and the nationally oriented Nature Conservancy (1951).25 The Georgia Conservancy was primarily an advocacy and educational organization, and though the organization did purchase land—the first such deal involved Panola Mountain, which is now a Georgia state park—land acquisition was not a primary objective. Members considered the conservancy a “purposeful organization” dedicated to active participation in the democratic process, but a cadre of former members established a splinter group in favor of aggressive lobbying tactics, shedding corporate influence, and improving organizational strategy.26 The Conservancy’s members—most of whom were white, affluent, and well-educated “businessmen, housewives, scientists, teachers, artists, naturalists, sportsmen, botanists, students, and young people”—gathered every fourth Saturday to explore their state’s wild, scenic, and recreational areas.27 The conservancy promised to provide “members a living awareness” of given ecological problems “by conducting field trips to natural areas,” including a well-attended mid-1967 outing to the Chattooga River. In the Chattooga’s case, the conservancy teamed up with the Georgia Canoe Association (established in 1966) on more than one occasion to sponsor canoe and hiking trips for members and the general public, as well as state and federal officials. The Georgia Conservancy’s and the Georgia Natural Areas Council’s members provided advice, expertise, and resources to keep the Chattooga free of hydroelectric dams and commercial development and, more importantly, running wild for all to enjoy.28

The Georgia Conservancy and Georgia Natural Areas Council shared members, executive officers, and scientific experts who likewise influenced the way people understood regional environments. These organizations also influenced the relationship between southern water and southern power in a democratic society managed by narrowly focused special interests. For example, Robert Hanie organized a “Chattooga River Seminar” at the Dillard House in Dillard, Georgia, in November 1968, two months after the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act declared the Chattooga an official study river. He pulled together bureaucrats and special interest groups, including forty representatives from the Forest Service, the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, and state development organizations, and resource managers from three states to discuss how they might collectively shift the Chattooga from study river to wild and scenic river. Lynn Hill, the Georgia Conservancy’s director, and William Dunlap, assistant to the president of the Georgia Power Company, also attended the meeting. Dunlap, a longtime executive with the company, frequently paddled the Chattooga’s whitewater, and his respect for the conservation community and his relationship with the company made him a valuable member of the river lobby in the late 1960s.29 This November meeting initiated a collaborative and cooperative coalition between federal and state bureaucrats and public and private interest groups who would continue to speak for Georgia’s environment well into the future.30

The Georgia Power Company was one of those interests. Long a player in state water and energy issues, Georgia Power was a major and unique actor in the Chattooga River’s story. Beginning in the 1920s, the company had acquired approximately 37 percent of the property (5,690 acres) necessary for the Chattooga’s fifty-mile-long and approximately three-mile-wide protective wild and scenic river corridor; the National Forest Service owned the majority of the remaining property.31 The New South company intended to build a series of hydroelectric dams and replicate the Tallulah-Tugaloo project. But a chronology of factors—including the public-private power debates over Muscle Shoals during and after World War I, the 1925 regional drought and subsequent shift to coal-fired generation, a lack of capital during the Great Depression, and the post-1945 development of civilian atomic energy technology—led Sun Belt Georgia Power executives to forgo developing five potential hydropower sites along the Chattooga.32 By the late 1960s, the fast-growing company became embroiled in a racial discrimination suit and feared competition as other energy companies such as Duke Power also invested in nuclear energy. To further muddy the company’s public face, Georgia Power encountered customer resistance to a proposed rate increase to finance future power projects—including Plant Hatch’s twin nuclear reactors on the Altamaha River (construction began in 1968) and Plant Bowen’s four coal-burning units on the Etowah River (1971)—while simultaneously reporting high revenues and profits.33 In light of these challenges, and after over half a century of landownership in the Chattooga watershed, the Georgia Power Company looked for a way out in 1968. Anticipating the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act’s passage, a Georgia Power Company spokesman announced that the company would “be most willing in the matter of land ownership to cooperate with groups interested in the Chattooga River,” and that the company did not intend to develop the river’s hydropower potential because such projects were “marginal from the economic view point.”34 With this decision, a wild river’s greatest enemy in the 1960s—the dam builders—backed away from the Chattooga during a national energy regime transition.

The wild and scenic river process presented Georgia Power with an extraordinary opportunity to extract itself from the Chattooga watershed. The situation provided the company with a chance to swap its Chattooga land with Forest Service property adjacent to the company’s Tugaloo Lake and the inundated Tugaloo River. This combined land purchase and exchange signified that the Chattooga land held little value for the company; indeed, it may have actually represented a liability from the perspective of management and state tax payments.35 The Tugaloo land, on the other hand, increased and consolidated the company’s land holdings in a recreational and leisure waterscape owned primarily by Georgia Power. The cooperative relationship between Georgia Power and the Forest Service served very narrow recreational ends, on one hand. The swap also protected a unique river and provided additional ecological and community benefits as envisioned by the Craighead brothers.

However, this network of private businesses, public officials, and environmental stakeholders included few full-time Rabun County (Ga.) and Oconee County (S.C.) residents. Both counties were in the midst of striking economic shifts, and these Sun Belt transformations only intensified after 1970. Rabun County experienced a nominal population increase of just over 900 people between 1960 and 1970, when it had a total population of about 8,300 people. The 370-square-mile county’s shift from agricultural and forestry employment was more significant; the county lost more than 175 positions and witnessed a corresponding increase of nearly 500 manufacturing positions, primarily in the “textiles and fabricated textiles” sectors.36 On the South Carolina side of the Chattooga River, the nearly five times more populous Oconee County (over 40,000 residents) grew much more slowly. But Oconee (650 square miles) gained more than 2,000 manufacturing positions while losing over 1,000 agriculture-related jobs. In these Sun Belt demographic shifts, the Chattooga River was an excellent retreat for a large body of nonagricultural employees in two states who lived within sixty miles of the river and may have already enjoyed this recreation destination. Rabun and Oconee County residents found themselves increasingly tied to time clocks that not only kept track of hours worked but also limited their recreational time in easily accessible southern Appalachian recreation commons like the lightly managed Chattooga River corridor.

Rabun and Oconee residents participated in discussions pertaining to the Chattooga’s federal designation to varying degrees. The “locals” who had long visited the river to fish or socialize or for other community uses had been described by wild and scenic river advocates as nonparticipants in the many private or public discussions about the river’s future. One nonparticipant, John Ridley, grew up on the Chattooga’s South Carolina bank, just upriver from the Highway 28 bridge; he attended Clemson University in 1961, where he received a horticulture degree. According to him, South Carolina and Georgia locals who had lived near the river did not participate in the process for two reasons.37 First, there was limited communication between folks who lived along the river and those who lived in Walhalla, Oconee’s county seat. As an illustration of this disconnect, his family never had a phone and did not receive electricity until 1952, despite the Southeast’s extensive electrical generation and transmission system. Their neighbors—the Russells—obtained the first community phone connection in 1968 before selling their property to the Forest Service in 1970.38 Second, Ridley interpreted the Chattooga’s transformation in a larger historical context of southern Appalachian community reaction to Forest Service policy. The Forest Service’s history of land condemnations in Georgia and South Carolina dating back to 1915 had left an impression with local residents that when the Forest Service threatened to condemn property, little could be done to stop the process. This early fear likely dated back to the Forest Service’s condemnation of thousands of acres of private property when it began to acquire land under the auspices of watershed protection and the Weeks Act (1911).39 It is worth noting that the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (1968) made land condemnation for river corridors very difficult, but land adjacent to and outside the future corridor—including in-holdings—was indeed condemned.40 Given this context, local people “did not think they could do anything or did not know about the process,” in Ridley’s opinion. Furthermore, farming families like his, who lived along the river before moving out in 1970, “lost interest after losing their land.” These families may have chosen not to participate, but that did not mean they did not care about the river. Ridley believed the “locals knew they took better care of the river” and that the “general public doesn’t take care of the property.” He also claimed that today’s visitors from outside the region—mostly raft, kayak, and canoe recreationists—leave their trash along a river that once provided his family with trout.41 Ridley was not alone in the opinion that local residents who cared about the Chattooga did not vocalize significant opposition to the river’s designation. Newspaper editors and their coverage on both sides of the river portrayed the initial wild and scenic river designation process as a love fest, with one paper noting “almost no opposition” at advertised public “listening sessions” as the study process kicked off in 1968.42

But beginning in 1969, conservation-minded critics—particularly from South Carolina—warned the Forest Service officials facilitating study sessions and public hearings that designating the Chattooga a wild and scenic river would require users, including local residents and outside visitors, to adjust their behavior within the protected river corridor.43 Attention to planned road and trail closures on the South Carolina side of the river, as well as potential restrictions on hunting and fishing access, occupied more than passing conversation at a Clemson meeting and foreshadowed future points of contention.44 Tension flared at yet another Chattooga-related public meeting when a lawyer from Greenville—a South Carolina city located about sixty-five miles east of the river—attacked the Forest Service’s clear-cutting policy, only to be rebuffed by resident loggers in the audience who responded that clear-cutting operations improved the forest’s health and provided jobs for South Carolinians. These South Carolina meeting participants—countryside conservationists to varying degrees—clearly identified the river as a local leisure and labor landscape and worried that the river’s official designation might result in reduced recreational access or a loss of forestry-related jobs in the face of increasingly centralized federal authority.45

River enthusiasts from Atlanta to Greenville, however, envisioned the river primarily as a leisure waterscape for nearby Sun Belt residents. Members of the Georgia Conservancy, paddlers from the Georgia Canoe Association, Georgia Power employees, and the Sierra Club’s Joseph LeConte Chapter formed a coalition. Private interests that cast themselves as publicly minded—such as the Georgia Conservancy—spoke for more privileged local and nonlocal folks.46 For example, conservancy member Fritz Orr Jr. lived part-time in Atlanta, and North Carolinian Frank Bell spoke before Congress in support of the river.47 Orr and Bell, both path-breaking southern paddlers, also owned and operated summer camps that utilized the Chattooga’s headwaters. The network was indeed deep: One of Orr’s Atlanta neighbors was Georgia Power executive Harlee Branch Jr.48 These nonlocal advocates were not the only river enthusiasts. Greenville attorney Ted Snyder, who grew up in Walhalla, twenty miles east of the Chattooga, had spent time on the river as a young adult and understood that the Chattooga represented the last of its kind in the mountain South. He spoke for the river on behalf of the local Sierra Club chapter and before congressional committees in Washington, D.C., as a Walhalla transplant living in Greenville.49

The Chattooga also had attentive friends in Washington who learned about the river’s value and popularity. In mid-1973, Congressmen Roy A. Taylor (D-N.C.), William Jennings Bryan Dorn (D-S.C.), James R. Mann (D-S.C.), and Phil Landrum (D-Ga.) cosponsored a bill to add the Chattooga River to the official list of wild and scenic rivers.50 This was in response to the favorable Forest Service staff report titled A Proposal: The Chattooga, “A Wild and Scenic River” (1970).51 This legislation sparked a congressional hearing process, and Dr. Claude Terry—an Emory University microbiologist, avid whitewater boater, and Georgia Conservancy spokesman—testified before a subcommittee charged with hearing public input on the Chattooga’s wild and scenic status in late 1973. Terry followed standard discourse on the need for balanced water management and declared, “Using a river for power production, building industries or homes along its bank or in its flood plains … are all consumptive uses which damage or destroy the stream itself.”52 The Georgia Canoe Association’s Cleve Tedford echoed concerns over development on southern rivers while shifting his focus during the hearing: “If the watershed of the Chattooga is not protected, then many of the values for which the wild and scenic river is cherished will vanish even though the stream bed and banks are preserved.” He expanded the discussion of river protection in language not unlike John and Frank Craighead’s back in the 1950s, and Tedford distinguished between river protection and watershed protection in an effort to push his congressional audience in the direction of the latter.53 He tapped into a growing ecological systems theory expressed by scientists like Terry but more clearly articulated by University of Georgia ecologist Eugene Odum, who viewed whole watersheds and activity on the land above the riverbank as more valuable and influential than protection of individual streams or rivers. Terry and Tedford presented persuasive arguments to shift the Chattooga from a study river to a wild and scenic river. They also got some help from Georgia governor Jimmy Carter, who had paddled the Chattooga not just once but multiple times. And Carter, an evolving countryside conservationist who would put a stop to Flint River dams, proved to be instrumental in lobbying congressional committees on the Georgia Conservancy’s behalf.54

South Carolina’s and Georgia’s congressional delegations also spoke for their constituencies in less scientific terms to support free-flowing rivers. James R. Mann (1920–2010), a five-term (1968–78) congressman from Greenville most well known for his drafting of President Richard Nixon’s articles of impeachment, recalled recreating on the riverbanks “since [his] earliest years as a school boy.” Senator Herman E. Talmadge (1913–2002) described the Chattooga as a “primitive, free flowing river” that offered excellent recreational values. Talmadge’s junior counterpart, first-term senator Sam Nunn (D-Ga.), painted a slightly different picture and worried that visiting crowds threatened the Chattooga’s recreational integrity. In Nunn’s opinion such overuse and impact justified federal management and “development of the proper facilities.”55 Each of these spokesmen communicated important reasons for maintaining a Wild and Scenic Chattooga River as one solution for the Sun Belt’s water challenges. Their interests in balancing the old policy of constructing dams, preserving wild watersheds, and maintaining watershed integrity joined two other major foundational aspects of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act—recreation and ecological restoration—as intended by the act’s authors, the Craighead brothers. The act did not specifically use ecological terminology but stated that “each component of the national wild and scenic rivers system shall be administered in such manner as to protect and enhance” the characteristics that contributed to a river’s inclusion in the national system.56 To enhance implies some degree of improvement or a landscape in need of hands-on management after centuries of human activity. The Chattooga indeed had been worked over by the lumber industry at the beginning of the twentieth century and was not the primitive wilderness many supporters claimed. But in the case of the Chattooga River, Senator Nunn and natural resource agency staffers were less interested in watershed protection and more interested in hands-on management to deal with the hordes of inexperienced paddlers who soon descended upon the river. Recreation—at the expense of ecological restoration—became a central part of the Chattooga’s story, but not necessarily in the “educational and spiritual” sense expressed by the Wild and Scenic River Act’s authors.57 The river’s popularity was a problem in and of itself.

The book and film versions of James Dickey’s Deliverance help explain the role recreation played in pushing the Chattooga from study river to wild and scenic river in 1974 and why the forest burned in 1976. Dickey’s novel (1970) and his subsequent screen adaptation (1972) introduced the country to the stunning and adrenaline-pumping Chattooga River. The basic story followed the epic trials of four suburban Atlanta professionals who floated the fictional Cahulawasee River before a hydroelectric dam and reservoir drowned the wild river forever. The film opened with construction images of Duke Power Company’s Jocassee dam (one component of the Keowee-Toxaway hydronuclear project) as a stand-in for the fictional Cahulawasee’s dam. Lewis, played by Burt Reynolds, intoned in an opening voice-over that the Cahulawasee was “just about the last wild, untamed, unpolluted, unfucked-up river in the South.”58 Dickey effectively communicated his opinion about special rivers like the Chattooga, and his narrative revealed the risky transformative powers that a wild South could bestow on people disconnected from nature. As the soft, inexperienced, and domesticated Sun Belt suburbanites descended an increasingly chaotic river, one member of the party was raped by a woodsman, two others committed murder, and a third drowned after the party “voted” to bury the first casualty without notifying the authorities. In the process of commenting on modernization’s dulling effect on individual freedom and the perilous consequences of wilderness exposure, Dickey’s screenplay also reinforced negative Appalachian stereotypes about a land of dueling banjos and backward mountain people.59 But despite the dark tale of male rape and murder on the Cahulawasee that leaves today’s campers apprehensive about spending a night in the watershed, the wild and raging riverscape on the big screen attracted thousands to the real Chattooga River.

In 1971, the year before the Deliverance film was released, the Forest Service estimated that 800 people visited the river annually. During the wild and scenic river study process, one Georgia State Game and Fish staffer commented on visitor projections, and he worried that a “loss of space and tranquility due to use by excessive numbers of people” was among the “greatest” dangers “on this river.” Furthermore, Claude Hastings believed that improved access to the river would actually invite recreational conflict between experienced and inexperienced river users.60 Time would prove Hastings right. Many of these early visitors undoubtedly learned about the unmanaged river from local and regional newspapers such as the Atlanta Journal Constitution. Others discovered the river via a network of paddlers and national boating journals like American Whitewater, which published two Chattooga boating guides prior to the river’s wild and scenic designation.61 The first generation of southern paddlers—including Fritz Orr Sr., Ramone Eaton, Randy Carter, Hugh Caldwell, and Frank Bell—had also introduced new boaters to the river as early as the 1950s. Many of these men either owned or worked for summer camps, such as Merrie-Wood and Camp Mondamin, in the southern Appalachians. This older generation initiated succeeding generations of paddlers—including Payson Kennedy, Fritz Orr Jr., Claude Terry, and Doug Woodward—to southern rivers, and they in turn established the most prolific guiding businesses of the 1970s that still operate today: the Nantahala Outdoor Center (Kennedy) and Southeastern Expeditions (Terry and Woodward).62 The film, however, introduced the river to a much larger and more inexperienced throng of leisure and thrill seekers. After Deliverance popularized the Chattooga’s wild rapids—with Terry, Woodward, and Kennedy hired as body-paddler-doubles for Jon Voight and Ned Beatty—river visitation jumped to an estimated 21,000 visitors in 1973.63 The movie infected would-be paddlers with a “Deliverance Syndrome” that led many to their deaths, according to Terry.64

Recreation, risk, and tragedy nudged the Chattooga closer to formal wild and scenic river designation. According to a Georgia Outdoors writer, the movie spawned traffic jams “and all but choked every access point; the river filled with jaunty adventurers in varied vessels—in kayaks and canoes, in rafts and rickety inflatable contraptions—each seeking in one way or another to prove himself (or herself)” equal to star Jon Voight or the other lead superstar. On screen, Burt Reynolds was the movie’s wet-suit-clad, cigar-smoking, bow-hunting-survivalist, and whitewater-paddling embodiment of 1970s masculinity. The Chattooga’s popularity, however, led to an increased number of recreation-related fatalities on the river. The banks “echoed the calls of search parties seeking the remains of those whose carelessness or naiveté proved terribly expensive,” according to T. Craig Martin.65 Some whitewater guide companies, including Claude Terry’s newly established Southeastern Expeditions, and other paddling clubs had formed explicitly to provide visitors with a safe introduction to the river. But not all river-runners sought guides or advice, and the mounting recreational dangers and a proliferation of guide services ultimately contributed to the river’s use, abuse, and upgrade from study river to full wild and scenic river. In response to the hordes and persistent lobbying by advocates and agency staff, in May 1974 the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River became an official component to the national system of protected rivers. And with congressional authorization, the Forest Service deployed river ranger staff and instituted a permit system to better manage guide companies and individual river-runners.66

Saving the Chattooga in the 1970s—made possible by the combined efforts of the Forest Service, the Georgia Power Company, and new environmental institutions—was clearly not entirely about saving wilderness. When the river was officially folded into the National Wild and Scenic River system in May 1974, the end of the designation chapter signaled a general agreement over the river’s unique qualities. But the management chapter chronicled the deteriorating relationship between the river corridor’s users and managers. The public and private network that shifted the Chattooga from a study river to a wild and scenic river did so in a self-contained manner that increasingly alienated a body of local river enthusiasts. According to Max Gates, the first official Chattooga Wild and Scenic River ranger, “mostly outsiders” supported the river’s designation. The former Sumter National Forest (S.C.) land manager explained that the Forest Service sponsored multiple, well-advertised public meetings in three counties in the three states adjacent to the Chattooga River before 1970, as well as additional meetings after 1974.67 But apparently only a “few locals” from North Carolina, South Carolina, or Georgia attended. Furthermore, the Forest Service had solicited comments from the newspaper-reading public before 1971 and received more than 1,000 responses supporting the designation, with only three outright dissents.68 While Gates may have exaggerated the lack of local participation, he adequately described the conflict that emerged after designation as a result of a “clash of classes,” or a clash between the local folks who preferred the ease of recreating on the banks and the growing number of visitors intent on traveling the whole corridor’s length on the river’s back.69

As Georgians and South Carolinians moved through the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River designation process in 1974, they took part in a much larger regional discussion about public land management. For example, at the time the Forest Service was revising national policy in the late 1960s and early 1970s. That topic is beyond this book’s scope, but it is sufficient to say that the Forest Service was in the midst of reshaping national forest management policy in an effort to balance even-aged timber management—also referred to as clear-cutting—with recreation, wildlife, and biological diversity.70 Nobody liked clear-cutting, according to Max Gates, and some local forest users chastised Forest Service officials for cutting hardwood trees that produced nuts. Game hunters and anglers in particular thought clear-cutting was bad for squirrel populations and fish. Indeed, Forest Service public relations specialists published regular columns in local newspapers in an attempt to convince Rabun County residents that forest management and clear-cutting improved conditions for wildlife. The Forest Service also provided locals with access to free firewood for personal consumption.71 But in the end, and in Gates’s opinion, local people resisted anything that disrupted the “way of life” in what they considered their forest community, despite the fact that many of the river’s recreational spots had historically rested on Georgia Power’s private property or public land.72 Or more plausibly, as historian Kathryn Newfont has observed in other southern Appalachian communities, rural and mountain residents understood the forests and rivers as places “to live rather than to visit.” For people who lived close to the Chattooga River, the valley was a space for baptisms, picnics, and relaxation; it was undoubtedly “a part of the fabric of everyday life rather than a retreat from the ordinary.”73

In the larger federal policy context, the southern Appalachians also became a battleground in the 1960s and 1970s as repeated intrusion by external interests threatened the composition of mountain communities. Not only did outsiders move in, buy second homes, and erect “No Trespassing” signs, but federal policy also imposed restrictions on public and private land use. New policies included declarations of eminent domain to acquire Appalachian Trail lands (National Trails System Act [1968]); the creation of eastern wilderness areas (Roadless Area Review and Evaluation I [1972] and the Eastern Wilderness Act [1975]); and a proposed extension of the Blue Ridge Parkway along Georgia’s ridgelines.74 Furthermore, at the time of the Chattooga’s full wild and scenic river designation in 1974, parcels of South Carolina’s public land near the river—such as Ellicott’s Rock and more than 37,000 acres in the Chauga watershed—were under consideration for wilderness and roadless designations. In both cases these federal designations would have eliminated logging and forestry jobs in those specific areas, a point articulated by local wilderness opponents as early as 1971.75 Against this backdrop, Rabun County (Ga.) and Oconee County (S.C.) communities thought they were besieged by the federal government’s reach into the mountain landscape. In response to these encroachments, residents on both sides of the Chattooga River began to vent their frustrations over increasingly restrictive land management policy that dated back to the Weeks Act (1911), when the Forest Service began acquiring property in the southern Appalachians, but that now centered on the Chattooga’s 1974 designation as a wild and scenic river.

No other issue sparked greater confrontation in the Chattooga region than the Forest Service’s October 1974 decision to close roads that crossed Forest Service land and entered the Chattooga’s new wild and scenic river corridor.76 Under the terms of the Wild and Scenic River Act (1968), river sections designated as “wild” were supposed to be “generally inaccessible except by trail.” Scenic and recreational sections could be “accessible in places by roads.”77 The Chattooga’s wild and scenic corridor—or the distance between the riverbank and the corridor boundary—was rarely more than one-quarter mile wide, and the corridor itself was generally surrounded by thousands of acres of Forest Service land. Chattooga River study personnel intent on meeting the designation standards first introduced the idea to close corridor roads and selected foot trails in 1969 and immediately encountered resistance from state fish and game managers who were concerned about how they would reach the river to restock fish or check hunting licenses. And in 1971 the Forest Service proposed closing up to thirty miles of roads.78 Despite the expressed concerns, Oconee County (S.C.) commissioners eventually transferred all the required road rights-of-way to the Forest Service prior to 1974, but their Rabun County (Ga.) counterparts did not. As early as 1972 the Rabun County commissioners had begun to hear arguments from both the Forest Service’s Max Gates and county residents on the issue of future road closures.79 By October 1974, Chattahoochee National Forest (Ga.) supervisor William Patrick Thomas facilitated a localized and back-channel road-closure agreement between Rabun County commissioners and Chattooga’s wild and scenic river managers. Georgia senator Herman Talmadge, chairman of the Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry who was embarking on his fourth and last term (1956–80), helped Thomas and Rabun County commissioners broker a deal that closed some state and country roads while keeping others open in spite of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act’s requirements.80 Plus, the Forest Service maintained three bridge crossings—including one U.S. highway, one state road, and one Forest Service road—within the protected river corridor for management and logistical reasons. Many longtime forest users, however, did not understand the uneven road closure policy.

After 1974, Forest Service managers continually used a public safety argument to justify the selective road closures in Georgia and South Carolina. In light of the high fatality rates and drowning incidents that resulted from the popularity of Deliverance, Forest Service personnel wanted to limit easy access to the river’s dangerous sections where visiting hikers and swimmers might (and did) get swept over rapids or pinned by the river’s current. Most of the local users did not float the river, but they had used the old roads to access favorite campsites, swimming spots, and picnic areas. Or as former Forest Service recreation planner Charlie Huppuch recalled, people would drive vehicles into the Chattooga River and wash them.81 When the Forest Service finally gated roads after 1974, most trout fishermen faced less than a one-mile walk “to their favorite holes.”82 These restrictions and user policies did coincide with the river’s evolution from a site of local leisure to a regional and national destination for select visitors or well-equipped river-runners. Despite the Forest Service’s and local newspapers’ attempts to explain the road closures before and after the fact, local residents who may not have chosen to participate in the designation process responded to what they interpreted as a continued loss of local control and traditional access rights to the river.

“Retro Frontiersmen,” as defined by the late Jack Temple Kirby, who had watched individuals, corporations, and federal agencies close the “open range” and enclose resources once considered freely accessible for generations, turned to an old tool and instrument of protest. The forest fires that raged between 1974 and 1978, according to one local historian, were arsonists’ responses to the Chattooga’s final designation as a wild and scenic river.83 Arson as a form of protest was certainly not new to the Chattooga River’s valley. In early 1972, two men and one woman were caught “setting woods fires” in the Warwoman Dell Wildlife Management Area.84 Wet conditions, however, thwarted attempted arson in the spring and fall of 1975, but drier conditions in February 1976 contributed to more than fifty fires that burned 800 acres on a single weekend in Georgia’s Rabun County. Chattahoochee Forest Service supervisor Thomas attributed the arson to a “fire-style protest of state and federal restrictions” by a minority of “angry mountaineers” deprived of access and “exiled” from the Chattooga River corridor. But he also linked the fire-style protest to the past, dating to 1911, “when the Forest Service began regulating timber cutting, closing access to protect rivers and blocking off old logging roads.” In the course of two short months during 1976, Georgia’s Chattahoochee National Forest lost 3,800 acres to fire in three counties—approximately as much forest burned in sixty days as had been burned in the previous two years—all in part of the larger local reaction to forest policy and federal intrusion throughout the mountain region in the 1970s.85 According to another source, between 1969 and 1973, South Carolina’s Andrew Pickens Ranger District—which the Chattooga River borders—incurred a yearly average of five fires with 18 acres burned. But in the five-year period between 1974 and 1979, twenty-three fires burned an average of 687 acres in the same district.86 After 1974, South Carolina and Georgia residents—initially respectful of the local recreational commons—assumed similar tactics to protest forest policy in Sumter and Chattahoochee National Forests, with residents displaying signs proclaiming: “You put it in wilderness and we’ll put it in ASHES.”87

Arson in the Chattooga River’s corridor represented latent protest against turning a local recreational commons into a federal recreational commons. It is important to remember that in the Chattooga’s case, the Forest Service did not “take” private land from unwilling sellers by declaring eminent domain; the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act made this tactic extremely difficult to implement but never impossible to threaten. Prior to the road closures, Georgia Power and the Forest Service already held title to 84 percent of the proposed wild and scenic river corridor, including some roads, and theoretically controlled access to existing informal campsites, swimming spots, and fishing holes.88 But after 1974, the conflict between insiders and outsiders, and between privileged locals and nonlocals, materialized over the issue of what constituted appropriate recreation in Georgia’s and South Carolina’s expanding and popular national forests.

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (1968) was a useful instrument for Sun Belt citizens who pushed back and against a half-century of the modern hydraulic waterscape’s assembly. The network of public and private ambassadors from the Georgia Power Company, the Georgia Natural Areas Council, the Georgia Conservancy, and the Forest Service participated in local and national hearings, communicated with elected officials, and mobilized a grassroots constituency to achieve a specific end. These parties—the “someone” Patrick Thomas identified as responsible for “taking away access” to the Chattooga—justified the river’s federal protection on post-Deliverance safety concerns, but more importantly because the Chattooga was, in fact, the last major undammed river surrounded by a sea of reservoirs in the mountain Sun Belt.89

The process also did not accommodate all local recreational realities and elicited a response that left the woods burning when the river corridor became a linear recreation space that catered to national and nonlocal consumers. Initially a fragmented local landscape composed of fishing holes and camping spots, the Chattooga became a unified wild and scenic river with clear start and end points for paddlers and boaters that visually muted the older intermediate recreation spaces. The Forest Service closed roads to secret spots and campsites and transformed fishing trails along the river’s edge into hiking trails on parallel ridgelines. This imperfect process maintained a wild and free-flowing river, but some local users lost a perceived freedom to access the river. While the Chattooga River’s story highlights how a private and public coalition transformed a local commons into a federal commons, the story also illustrates that the conflict did not revolve around whether the river should have been conserved but over how this federally managed and unique river would be used and by whom.

New South, New Deal, and Sun Belt economic interests had attempted to resolve the region’s water and energy challenges with canals, dams, reservoirs, levees, and deeper channels. Private and public engineers changed rivers’ shapes, forms, and functions to cope with problematic flooding and drought. Another coalition of postwar southerners reevaluated those old supply solutions to the region’s water problems and moved in a completely different direction. Like allies around the nation, the Sun Belt’s countryside conservationists and environmentalists thought dams and river structures were the problems and not the solutions. For these engaged activists, the Wild and Scenic Chattooga River solved a new problem: In a region that lacked significant free-flowing rivers, the Chattooga’s new designation broke with the past and illustrated a new relationship between southern water and southern power.

Author John Lane has described his personal Chattooga experiences to illustrate why the river attracts people and what the river delivers to those who know and use it today. As a nature writer, Lane tapped into what people have taken from and what expectations people have of the river shed, including water quality concerns of longtime headwaters residents; observations of the riverscape by literary and academic visitors; backcountry experiences sought by backpackers; and the ambivalence of the residents of Clayton, Georgia, over the impact of Deliverance on their community. Ultimately, he interprets the southern landscape as sublime on its own terms, in terms that Rabun and Oconee County residents from yesterday and today would agree with, including those residents who continue to believe the river was taken from them.90 Bearing Lane’s context in mind, we should remember that in the end, through a series of choices in a century of energy regime transformation, the spectacular Chattooga River, the star of Deliverance, was consciously left wild, or at least undammed by the Georgia Power Company and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and was delivered to the national whitewater boating and environmental community for safekeeping.