Anti-Alien Property Laws

Although his name was Lue Gim Gong, Floridians knew him as the “wonder grower” or “citrus wizard.” A Chinese immigrant, Lue arrived in San Francisco in 1872 when he was twelve years old and quickly went to work with his uncle, an established merchant and labor contractor in the city. When Lue was sixteen, his uncle sent him to North Adams, Massachusetts, to work in a shoe factory. Lue’s easy demeanor and quick embrace of Christianity won him the affection of the powerful Burlingame family, who attended church with Lue. Solomon Burlingame offered Lue a job translating Chinese documents for his business, allowing Lue to strengthen his English language skills and become close friends with Solomon’s spinster daughter, Fanny Burlingame. Fanny became a mother figure to Lue and encouraged him to convert to Christianity and even assisted him with becoming an American citizen in 1877. In 1886, Fanny bequeathed five acres of land in Deland, Florida (near Daytona Beach), to Lue.1

Lue thrived in Florida, making good use of Fanny’s investment. Lue diligently worked at developing hardier strands of citrus that could withstand the sometimes unpredictable Florida climate, and in 1888, he created the Lue Lim Gong orange. By 1911, the Lue Gim Gong orange was a nationwide success. Lue was well respected by the white population of Deland and surrounding areas in Florida, a significant achievement for a Chinese man after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Perhaps, in the midst of a nation growing increasingly anti-Asian by the 1920s, Florida and more generally the South could be seen as an island of relative tolerance.2

Or perhaps Lue’s success and popularity among Florida whites were the result of him merely being in the right place at the right time, before the state would join in a national attempt to limit Asian American property rights. In 1926, one year after Lue died, the state of Florida amended its constitution to include a passage barring aliens ineligible for citizenship from owning land. Although “aliens ineligible for citizenship” was a broad category, by 1925 the phrase was racially coded in American political discourse as generally referring to Asian immigrants barred from entering the United States under the Immigration Acts of 1917 and 1924 and prohibited from naturalizing under the Naturalization Act of 1906. If Lue had arrived in Florida in 1927, his ability to become a landowner would have been questionable: He was an American citizen, but he was associated with a racial group “ineligible for citizenship.” It is difficult to tell how he would have been received by Florida residents at this time and if he would have easily been able to own property and become the citrus king. Lue’s case is exceptional, but it raises questions of the position of Asian Americans in the South vis-à-vis their immigrant status and highlights the xenophobia present in southern racism and its connections to discriminatory movements against Asian immigrants in the West.

Rather than a significant turning point, Florida’s radical change in its constitution was a culmination of growing southern fears of a “yellow invasion” during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Chinese labor experiment was short lived in southern states such as Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas, but as soon as the fear of labor competition died down by the turn of the century, a new wave of fear over Japanese encroachment on land washed over the South in the early twentieth century. As Japanese immigrants settled in California, Washington, and Oregon following Chinese exclusion in the early 1900s and found work as migrant laborers or later became successful farmers and business owners, West Coast residents feared a Japanese takeover of their land. In response, California and Washington passed laws that barred aliens ineligible for citizenship from owning property in 1913 and 1921, respectively. As a result, whites in the South worried that a “yellow horde” of Japanese was headed their way, fleeing the racism and discrimination in the West. True, more Japanese and Chinese did begin to come to some southern states during the early twentieth century, but they were not refugees from western land laws and they did not come in larger numbers. However, southerners interpreted this small stream as the forerunners to a deluge. In response, southern states enacted their own anti-alien land laws or went so far as to amend their constitutions to deter Japanese Americans from settling within their borders.3 While the measures targeted Japanese, all Asian Americans became suspect in the South regardless of ethnicity.

Typical stereotypes of both Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans as heathens, dirty, diseased, shifty, and greedy also did little to convince southerners that Asian Americans would not drastically alter the racial or economic landscape of the South. When southern states passed laws that barred Asian Americans from owning property, they were not only protecting their land; they were protecting basic ideas of citizenship and defining the term in their own ways. Although the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed the right to landownership for anyone living in the United States, southern states argued that such rights were basic tenets of American citizenship alone and not fit for Asian immigrants. Although African Americans were not the ideal citizens that whites had in mind, they were at least born in the United States, and unlike the heathen Chinese or the shifty Japanese, land and protection of property were guaranteed to them. In response, white southerners shaped the anti-Asian legal action in a region of the United States that actually held few Asian Americans.4

But Asian immigrants in the South, although few in number, did not easily accept this infringement on their property rights. From the late nineteenth through the early twentieth century, Asian immigrants in Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and Florida faced a form of legal discrimination that no other group faced in attacks on their rights to property and earning a living. While historians have pointed to the challenges of leasing land under the sharecropping system and restrictive housing covenants, Asian immigrants also faced violations of property rights, as southern states used landownership to define and codify citizenship as “white.” In response, some Asian American groups defied the laws by continuing to operate as usual, while others launched successful legal battles against state governments and their anti-alien laws.

Asian Americans faced unique legal challenges in the South, and the anti-alien land laws were not merely another form of Jim Crow for another race. Asian Americans were not separate but theoretically equal; the discrimination Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans faced in the South with landownership was a statement of their perpetual racial otherness and inability to assimilate and naturalize. The fear of what Asian immigrants could do as racial menaces more than what they actually did in the South shaped southern law. The amendments and laws were vague and problematic and did not immediately impact many Chinese American or Japanese American landowners; however, the anti-alien legislation discussed here codified Asian Americans as racial outsiders without citizenship rights, setting the stage for future legal activism.

Following the Chinese labor fiasco of the post–Civil War years, whites were content to watch from afar as another “race problem” unfolded on the West Coast, this time involving Japanese immigrants. Beginning in 1868, the Japanese Meiji Dynasty encouraged migration to Western nations to help Japan modernize and industrialize when Japanese citizens eventually returned home. Japanese who agreed with their government’s plan or small-market farmers who could not compete with the rise of commercial agriculture and resulting high land taxes in Japan settled in California and Hawaii. While many Japanese laborers went to Hawaii seeking job opportunities in the sugarcane fields, others came to the West Coast for migrant labor or were later able to use savings to invest in land and business ventures. Truck farming, or small-scale farming with produce hauled to markets, became a profitable form of income for Japanese living in California’s inland valleys. Japanese Americans took advantage of California’s temperate climate and extended growing seasons to harvest a virtual cornucopia of vegetables and fruits and used their expertise in irrigation to grow asparagus and lettuce. Eventually, Japanese Americans would come to own 450,000 acres of land in California and contribute 10 percent to the state’s revenue from agriculture. When farming failed to live up to income expectations, Japanese Americans turned to migrant labor, following the harvesting of different crops along the West Coast. With their nation encouraging them to serve as “pioneers” by crossing the Pacific and settling in the United States combined with the bountiful opportunities for economic growth, Japanese immigrants made their way to the West Coast by the thousands during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By 1920, there were more than 100,000 Japanese Americans living in the United States, mostly in California.5

Initially, Californians and others along the West Coast tolerated Japanese Americans, but this attitude quickly changed by the early 1900s. Whites at first granted Japanese Americans certain leeway, seeing them as a more worthy and respectable class of immigrants than the Chinese. Japanese Americans did not appear to be an immediate economic threat as they focused primarily on small businesses and farming in areas where few others dared to invest money and time in order to make the soil profitable. As a result of the business acumen of Japanese Americans, there was also little fear of labor competition with the working class, a resounding difference between the reception of Japanese Americans and Chinese Americans earlier on. However, West Coast residents changed their opinions of the Japanese immigrants when Japan secured a stunning defeat of the Russians in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905. Americans and indeed the world were shocked that a small, “yellow” nation could overpower the mighty Russian empire. The Japanese themselves viewed their victory as a foundation for the rise of Asian power, but Americans on the West Coast feared that Japan’s muscular foreign policy would serve as the impetus for further Japanese “infiltration” of the United States. Suddenly, Japanese Americans were transformed from an industrious and talented people willing to work hard to transform the California landscape to land-hungry, ruthlessly imperial, and “shifty” immigrants bent on dominating the white race.6

Californians engaged in an extensive campaign to discriminate against Japanese Americans in hopes of dissuading them from permanently settling in their state and to prevent a “second Asiatic invasion” of America more generally. Groups such as the American Legion and the Asiatic Exclusion League distrusted Japanese Americans and saw them as little more than subversive agents working on behalf of the Japanese government, while Democratic senator James D. Phelan became known throughout the country for his passionate devotion to Japanese exclusion. Phelan explained that Japanese immigrants were not in America to create new lives for themselves but, rather, to “colonize” the United States, and “a Japanese colony under the American Flag is not compatible with the growth of America.”7 With the urging of Phelan, the American Legion and similar organizations compiled reports based largely on anecdotal evidence that Japanese farmers routinely had belligerent encounters with white land-seekers and were in the process of establishing a monopoly on California’s agriculture industry. Many labor unions also feared that more Japanese would replicate the downward pressure on white wages caused by the influx of Chinese labor in the previous century and create unwanted job competition. The legion, anti-Asian organizations, West Coast politicians, and American Federation of Labor leader Samuel Gompers pleaded with Congress for an exclusion act for the Japanese and made numerous trips to Capitol Hill to testify to the ongoing battle between whites and Japanese along the West Coast. Congress, however, hesitated to engage in such measures and jeopardize diplomatic and economic relations with Japan. Dismayed by the lack of federal action, Californians and local leaders turned to their state legislatures and local governments to discourage Japanese immigration. In 1906, the San Francisco school board attempted to segregate Japanese from white children in city schools, prompting a backlash from both the Japanese government and U.S. federal officials. When violent white mobs attacked both Chinese and Japanese homes and businesses in Vancouver, Canada, later in 1907, both the United States and Canada agreed that some measure was to be taken to gain control of Japanese immigration. In order to ease tensions between Tokyo and Washington, D.C., as well as stem the tide of Japanese migrants, President Theodore Roosevelt met with representatives of the Japanese government in 1907 to work out a compromise. The resulting Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907 was a bargain between the United States and Japan: America promised not to discriminate against Japanese immigrants, and in return, the Japanese government agreed to stop issuing passports for manual laborers to come to the United States. Both governments recognized the agreement as a suitable compromise, but Californians and others along the West Coast who vehemently opposed further Japanese settlement viewed it as a setback for American interests.8

Despite the rising tensions between Japanese Americans and whites in California, the Japanese government continued to encourage its subjects to settle in America. Japan closely monitored immigration and provided much support for those who chose to settle in the United States. Although the American Legion and anti-Japanese groups found a grain of truth in Japan’s use of the words “colonies” and “colonization” to describe immigration to America, Japanese American farming colonies were conceived of as an economic form of expansion as opposed to a political takeover of the United States. Similar to other immigrant groups who established cooperative farming communities in the United States, such as the Swedes in southern Florida during the late nineteenth century, Japanese emigrants often pulled their resources, sought investments from American or Japanese businessmen, and/or received financial or administrative support from the Japanese government. The colony model established a pattern of settlement in California, and cooperative farming was a way for Japanese immigrants to raise the money for irrigation and supplies. Japanese American colonies, such as the Yamato Colony in Livingston, California, raised the suspicions of whites more than the activities of smaller family farmers because the colonies were often self-contained, with their own stores, schools, and even post offices. Word traveled that the Japanese were supposedly isolationist and unassimilable with little desire to acculturate or interact with Americans.9

Meanwhile, Japanese immigrants who were merchants or otherwise not engaged in manual labor looked to the rich soil of the South for land opportunities far from the virulent anti-Asianism and discrimination of California. By the early 1900s, the South was well past Reconstruction and into the New South era. Attempts to bring the southern states up to the industrial and productivity level of the North shaped the southern economy. Many planters and farmers sought to reinvigorate some of the lagging agricultural industries, including rice and sugarcane, by learning more modern farming methods. Fortunately for white southerners, Japanese Americans were eager to stake out a claim to land unsettled and generally underused in the South and rejuvenate and/or establish new crops and agricultural practices there. Early on, there was a mutual interest between Japanese Americans and southerners in one another that created the potential for a profitable relationship, a scenario that was different from and more inviting than the racial backlash that plagued the West Coast.

Japanese Americans turned their attention to the Gulf of Mexico region of the South and its rice industry. Until the Civil War, most rice in America was produced in South Carolina, with only small-scale farmers cultivating the crop in Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, and the plains of Arkansas. However, when the war decimated the Carolina rice industry and the growth of railroads opened up more markets in southwestern Louisiana and the Texas Gulf region, investors and farmers scrambled to capitalize on new opportunities. In 1899, Louisiana rice planter Seamann A. Knapp turned to Japan to learn more efficient ways of growing rice and, with the assistance of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, traveled to Japan to consult with rice farmers there. Seamann later imported to southwestern Louisiana the Kyushu strain of rice, or “Jap rice,” which was heartier and more resilient to the new, industrialized milling process of the postwar era, as well as a small group of Japanese planters with experience in more sophisticated irrigation and planting methods. Both Seamann and the Japanese rice planters benefited from the previous efforts of Japanese cotton grower Jokichi Takamine in establishing a productive business relationship between Japan and Louisiana in the 1880s. Eventually, more Japanese turned to rice production in Louisiana and Texas as new opportunities for colonies.10

Many Louisianans were initially excited about the possibility of Japanese settlement in their state. Newspapers reported Japanese interest in Texas during the early 1900s, and authors wistfully yearned to see Japanese establish themselves in Louisiana instead. In 1904 the Houston Chronicle noted that a “Mr. Akioki, a Japanese of distinction,” visited San Antonio to investigate the climate and resources of a 10,000-acre tract of land he purchased with the intent of bringing 300 families from Japan and the West Coast to Texas to form a “colony of his countrymen” to grow tea and produce silk.11 The article noted that whites in Texas “expected that the newcomers will make good citizens and intermarry and coalesce with Texas neighbors” and wondered if the same could be possible for Louisiana—a far cry from the belief among West Coast whites that the Japanese could never acculturate. Another article commended Akioki for his attempts to locate his colony on rich soil that until recently had been used only as grazing land for cattle, highlighting the innovation and gumption of the Japanese.12 Louisianans were so enamored with the reputation of the Japanese as skilled agriculturists and horticulturists that when a court in Houston declared in 1905 that Japanese were ineligible for citizenship (well before the Supreme Court decided the same in 1922), an article in the Shreveport Caucasian bemoaned the decision as “a serious one” because it had the potential to dissuade Japanese from colonizing in the state and elsewhere in the Gulf region. The author argued that the Japanese “are to be preferred to the Italians and others who are being brought in rather large numbers” to perform manual labor in the fields. “The experience with the Japanese in Texas is that they make model citizens, whereas many of the Italians and Polanders do not. The Polanders are clannish and unwilling to change any of their customs.” The author’s views on the Italians reflected an incident earlier in 1891 when a large mob of New Orleans citizens stormed the Orleans Parish Prison and lynched eleven Sicilian men who had been charged with the murder of a police chief but acquitted of the crime and were being held in the prison for safekeeping. When compared with the undesirable Italian immigrants and the chaos they brought with them, the Japanese were a welcome ethnic addition to the state’s varied demographics.13

In November 1904, Masahi Takenouchi, vice commissioner of Japan’s agricultural department, and Tetsutaro Inumara, imperial commissioner to Louisiana, traveled to the small town of Welsh in Calcasieu Parish in southwest Louisiana to investigate the growing conditions for rice. Baton Rouge commissioner William C. Stubbs, a classmate of Inumara’s when they studied together at Tulane University, had invited the duo to the state to discuss trade relations between Japan and Louisiana. Stubbs placed Takenouchi and Inumara in touch with Welsh planter Paul W. Daniels, who agreed to lease 300 acres of land to thirty Japanese farmers set to arrive in March 1905. Rather than grow only rice, the proposed colony would cultivate potatoes, cotton, and an assortment of vegetables to test the depth and fecundity of the Louisiana soil. Locals were intrigued by the prospect, believing that “experimentation with a new crop could prove a boon to the entire rice-growing section of the South.”14 Although citizens looked forward to watching the “outcome with interest,” they were sorely disappointed when they learned in February 1905 that “the experiment will be delayed a year,” a decision “regretted by many who were anxious to see the outcome of the Japs’ efforts.”15 Residents also religiously followed the travels of Japanese officials and representatives who came to Louisiana searching for profitable land, cheering when the delegations declared their state’s rice belt more favorable than that of Texas. When the official representative for all Japanese colonies in America, H. Kito, came to St. Landry Parish and was “highly impressed with the lands and conditions found here, saying that our irrigation system and lands looked better to [him] than any [he] had seen anywhere,” the citizens of St. Landry reveled in the fact that their home might attract Japanese colonies like those in other states.16

Florida became another site of bright opportunity for Japanese colonists at the turn of the century. Like Lue Gim Gong, who used the Florida soil to revolutionize citrus growing, Japanese Americans looked to the Sunshine State’s endless tracts of undeveloped and underused land for colonization sites. From the eastern coast of Florida to the central region known for its citrus groves, the land in this region could be a veritable agricultural gold mine—for those who were willing to undertake the work of clearing out scrub or swampland and going through the trial-and-error process of discovering which crops were most suited for the climate and earth. Few small farmers in Florida were willing to take the chance on such financially risky ventures, but larger industrialists, particularly railroad barons, were interested in developing land to expand markets and tracks. The stretch of coastal land between Jacksonville and Miami (still a “backwater” town at this time) was relatively untouched and underdeveloped, but it caught the eye of railroad magnate Henry Flagler in the early 1900s. Flagler, head of the Florida East Coast Rail Road, was interested in extending the lines down the coast to increase use through tourism and agriculture, but he needed individuals or groups who were willing to do the hard work for him. Flagler established the Model Land Company in 1903 to subsidize the cost of land and provide shipping discounts for those hardy settlers with the dedication to carve out a potentially profitable living on Florida’s east coast.

Flagler placed his business associate, James E. Ingraham, in charge of recruiting settlers. Ingraham took out ads in Florida newspapers and other periodicals across the country to entice farmers and reached out to business professor William Clark at New York University (Ingraham’s alma mater) for more advice. Clark provided Ingraham with contact information for Joseph Sakai, a graduate of New York University who was currently conducting business on the West Coast. Sakai eagerly responded but wanted to investigate potential sites for the project beforehand and arrived in Jacksonville in 1903 to speak directly to the stockholders of the Model Land Company. The company directed Sakai to land outside Boca Raton, a small community near Fort Lauderdale that served as a shipping center for the small numbers of winter vegetables and peppers grown by local farmers. Sakai traveled to Boca Raton with Ingraham and other representatives from the Model Land Company and was pleased with the soil and climate, foreseeing opportunities for growing citrus fruits and other more exotic products such as pineapples. Soon thereafter, Sakai entered into an agreement with Ingraham whereby Sakai would return to Boca Raton to begin farming no later than August 1904 and the Model Land Company would subsidize the Japanese for the cost of equipment and housing (which would later be repaid by the Japanese as soon as their colony gained footing).17

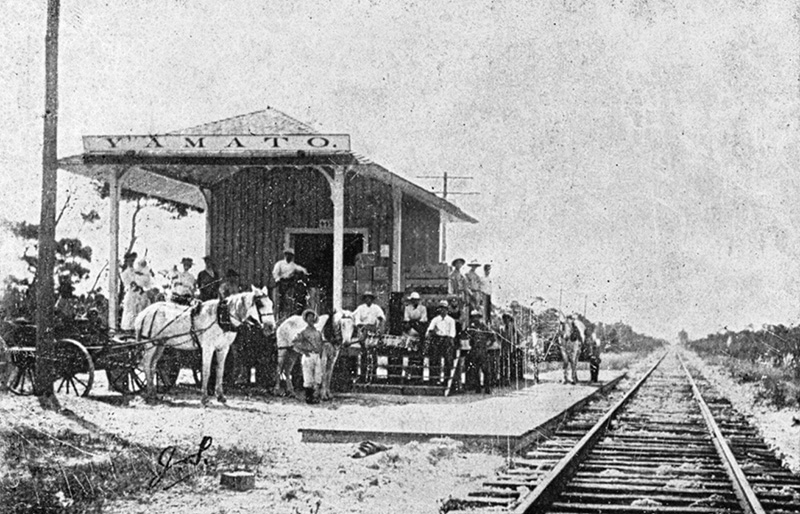

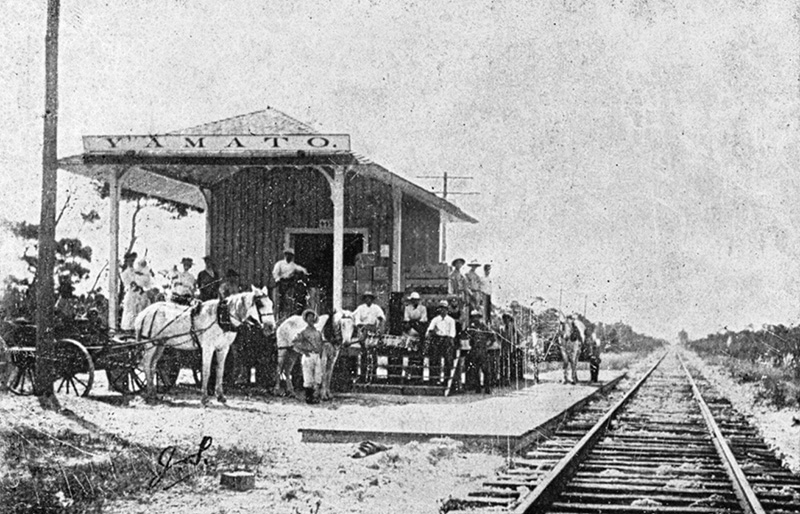

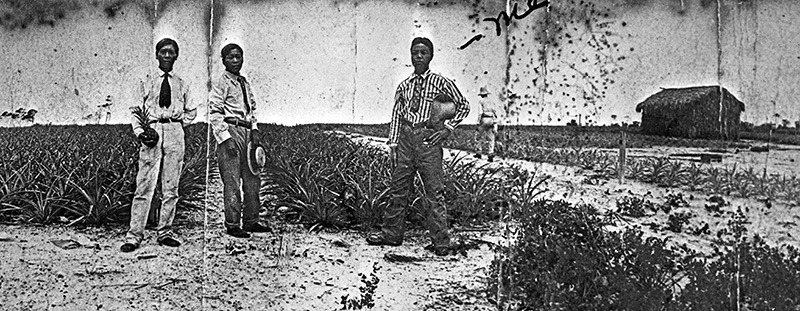

Later that year, Sakai returned to Japan to enlist ambitious families who would come to Florida’s Yamato Colony. Sixteen Japanese farmers came with Sakai, and Flagler agreed to pay for their passage from California to Florida. Initially, running the colony and turning a profit was difficult: The Japanese settlers were unaccustomed to Florida’s often muggy and oppressive tropical climate, illnesses such as malaria wracked the settlers, and blight decimated the early pineapple crops in 1905. However, in 1906, despite Sakai’s sudden death from tuberculosis, the colony prospered as the Japanese learned which crops grew more efficiently (tomatoes and cucumbers) and became more skilled at pineapple cultivation. Once established, the Japanese men sent for their families and turned Yamato from a bachelor’s society of “lonely farmers who would gather in a packing shed on Saturday night to socialize after their week’s work in the fields” into a “cluster of two-story frame houses, a general store . . . and some packing houses where pineapples and tomatoes were taken before being shipped north” on the Florida East Coast Rail Road.18 Nearby residents took note of the thriving Yamato Colony and reported on the “two cars of pineapples exported to England” and the “800 crates of tomatoes, which netted . . . $2 a crate.”19 Nearby white Florida residents initially congratulated the Japanese at Yamato on their “enterprise, ambition, and hard work” as well as their fields, which were “as handsome as any to be found on the East Coast, and the cultivation under which they are kept is a marvel to the ordinary grower.”20 One Florida resident who heard through the rumor mill that the Yamato Colony was looking to expand further into Dade County succinctly summed up the positive effects of the Japanese undertakings: “A hard surface road will be built out to the new settlement, and then watch the country around here develop.”21

The clear success of Japanese Americans in cultivating the difficult land earned them early respect from many Floridians. Because Yamato was a prosperous colony and the colonists there introduced new forms of agriculture that could easily be adapted by other farmers, the Japanese, though “yellow,” had proven that they could meaningfully contribute to society. The Florida Farmer, a popular statewide periodical for agricultural news, described the colony as “intensely patriotic” and the Japanese there as “working everyday to advance the general welfare of the state.” The Yamato Colony’s creed demonstrated that these were no temporary settlers like the Chinese or other groups but, rather, people who had “the interests of the state of Florida . . . really at heart.” In addition to “encouraging and developing the spirit of colonization among our people of Japan toward the United States” and “building upon our ideal colony to inculcate the highest principles and honor as a Japanese colony,” the people at Yamato also made it their duty to “study and improve local farm work” and to “introduce Japanese industries which we can adapt to the place and which may tend to advance the industries of Florida and secure mutual benefits.”22 Floridians who became familiar with the purpose of the colony came to see the Japanese as friends rather than foes in economic and business relations. So long as Japanese Americans were working to help revive agriculture and remained respectful, they were welcomed.

Japanese American farmers and their families at the depot of the Florida East Coast Rail Road at Yamato Colony, ca. 1909. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

Following the success of Yamato, many Floridians cried out for more Japanese colonies in their state. Dollar signs and the potential for agricultural diversity created an atmosphere in Florida different from that in California for Japanese Americans. Residents of Madison County in northern Florida (near Tallahassee) wistfully hoped that more Japanese would move farther north. “Again, we rise to remark that a Japanese colony in Madison County would be a good thing. We believe they would make excellent citizens and we’d like to see a colony of them located in the county, wouldn’t you?”23 Powerful businessmen in north Florida agreed that Japanese migration to the state was not only desirable but necessary. In February 1903, well before Sakai established the Yamato Colony, the Jacksonville Board of Trustees hosted a meeting of area businessmen to discuss the potential for Japanese settlement in Florida. Chamber of Commerce president Charles E. Garner delivered the keynote address and spoke out against the rising anti-Japanese attitudes on the Pacific Coast. Garner argued that an exclusion act for the Japanese similar to that of the Chinese Exclusion Act “would injure Florida” and deny the state the benefits of welcoming the Japanese who were “well-versed in advanced horticulture” and other agricultural practices. “As laborers in our mines and turpentine farms, we need them—as domestics they are unsurpassed. Florida and the south need such workmen.” Similar to first impressions of the Chinese after the Civil War, the presumed racial characteristics of the Japanese were more favorable than those of African Americans, and the Japanese would ameliorate rather than contribute to race problems in the South. Although the experiment with Chinese labor failed during Reconstruction, here was another opportunity to economically benefit from a new group of laborers and entrepreneurs.24

George Morikami (far right) with two Japanese American farmers in a pineapple field at Yamato Colony, ca. 1906. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

Others emphasized that Floridians did not share Californians’ opinion of Japanese Americans and welcomed them to their state. Unlike Californians, northern “Floridians are gratified to hear of [Japanese] success and applaud their desire to draw more of their kind. The little brown men are doing a good work for themselves and for us—it is still true that Florida is not California.”25 A resident of Pensacola insisted that “unlike the conditions existing upon the Pacific Coast, these thrifty little Japs are highly respected by their American neighbors,” and “the people of Florida . . . are much pleased with the little Orientals and hope that more may decide to immigrate to the state.”26 This indeed appeared to be true at Yamato, where the Japanese and locals mingled at festivals and celebrations. Sakai’s Japanese wife (who was eighteen at the time) was even granted permission to attend the local white high school.27 When the Japanese consul general Chozo Oikee traveled to inspect the conditions for his countrymen at Yamato, “he expressed great pleasure at the friendly spirit shown by American neighbors.”28 In general, the prosperity and agricultural knowledge the Japanese brought with them made many Floridians feel grateful that there were colonies established across the South and insistent that “a warm welcome await[ed] them [Japanese] in Florida.”29

Rather than expressing angry hyperbole or virulent attacks on the character of Japanese Americans as seen in California papers, Floridians initially spoke highly of what they saw as the innate, racially bound traits of the Japanese. The Gainesville Daily Sun’s editor was proud of the “little Japan down the East Coast that is much better than an Oriental colony in a big city” and reported that “the people of the surrounding county think well of the Japanese, for the latter are a sociable, well-mannered set and would not for any consideration pass you on the road without waving their arms in salutation.”30 In living with Floridians, Japanese Americans had earned the respect of the natives by engaging in southern hospitality and charm and displaying their affable nature. The Florida Farmer cheerfully confirmed that “there is not a lazy bone in the body of these people and they have a way of working that makes every effort count.”31 Floridians were happy to report that “their Japanese” were hard working, honest, and friendly people who were more than willing to adapt “themselves to American ideas in their manner of living and dress.”32 Overall, many in Florida agreed that the Japanese, far from posing a threat, were instead a “desirable class of settlers.”33 Just a few decades after southerners rejected Chinese labor, the South led the nation in affection for Japanese Americans.

Floridians went so far as to claim that the Japanese would one day make excellent American citizens, a fairly radical concept at a time of anti-Asian hysteria on the West Coast. Most of the arguments for citizenship for the Japanese rested on their profitability and demonstrated American work ethic. These were not “shady” or greedy individuals but a race devoted to personal fulfillment and achievement while contributing to the growth of their communities. Citizens in Punta Gorda on the Gulf shore of the state marveled at “a Jap who came to this country less than four years ago” and who raised rice on a 230-acre farm in Texas, noting that the Japanese “are a thrifty lot, and making good citizens” in the country.34 Holly Hill residents buzzed with excitement when rumors that a group of Japanese had purchased a large tract of land nearby to build a colony. The Japanese “while not likely to prove of social benefit, would enhance property values and . . . prove good citizens.”35 Floridians near the Yamato Colony noted that the Japanese were already “fully imbued with the American spirit” and that their “highest ambition is to be called Americans and citizens of this country, which they greatly admire.”36

In the early 1900s, there were more newspaper articles and opinion pieces from supporters of Japanese colonization and citizenship than from individuals who opposed it in Louisiana and Florida. Not only did Japanese Americans bring their knowledge and skills to the South to reinvigorate agriculture and contribute to economic development following the Civil War, but Japanese Americans, by virtue of their desire to farm, were deserving of American citizenship. Whereas many on the West Coast argued that the innate racial characteristics of Japanese Americans prevented them from assimilating and therefore disqualified them for citizenship, southern whites argued the opposite. Japanese Americans did have distinct racial characteristics, but those characteristics made them hardworking, honest, and model American citizens. When Japanese Americans formed colonies in the South, there were few objections to their landownership. The fact that the Japanese were willing to purchase and develop the land that no one else wanted made them more suited for acceptance in American political, economic, and to a degree, social life. There was no question that landownership was nothing less than a right for those willing to work for it, and if southern states could benefit from Japanese settlement, all the better. White southerners not only welcomed Asian immigrants but actively sought out their agricultural expertise. Japanese Americans had more to offer to the New South than African Americans. Respecting the rights to landownership and access to basic civil rights went hand in hand with expecting Japanese Americans to give back to the South. It was a reciprocal relationship that was uncommon for Asian immigrants outside the South.

But the generally positive attitudes toward Japanese Americans did not last. Following the Gentlemen’s Agreement and the failure of Congress to pass a bill that would place a restriction on the number of Japanese entering the United States, West Coast legislatures devised their own methods of discouraging the arrival and settlement of Japanese. West Coast residents worried that a growth in American-born Japanese children meant a new threat to property ownership and the American way of life. Knowing that truck farming was a profitable enterprise for many Japanese immigrants, politicians decided to attack what they identified as the root of the problem. If they could prohibit Japanese from owning or leasing property, then theoretically the West Coast would become a less desirable place for the “yellow menace.” Let the Japanese go elsewhere in the country if they must, but if the West Coast were less attractive, then there might be a chance to exclude Japanese immigrants from owning land if not exclude them from coming to the United States entirely. In other words, if the federal government would not pass a Japanese exclusion act, then the states, relying on creative interpretations of their constitutional rights to self-regulation, would take matters into their own hands.37

California and Washington became the earliest states to pass specific laws prohibiting aliens ineligible for citizenship from owning and leasing property. Such measures were not entirely new. Long before the arrival of Japanese immigrants, California, Oregon, and Washington had amended their state constitutions to exclude specifically “Chinamen” (Oregon), anyone who was not either white or of “African descent” (California), and those who were not willing to sign an intent to “naturalize in good faith”—effectively Chinese who could not become U.S. citizens—as part of a land deal (Washington). Other states, including Minnesota, Nebraska, and Texas, placed restrictions on the number of years an alien could own property or limited special government benefits for settling land to citizens or those who could naturalize. Discriminatory land measures were already in place and targeted primarily Chinese immigrants before the early twentieth century, but the new laws coming out of California, Oregon, and Washington in the early 1900s were more specific. The politicians who proposed and supported the acts or amendments to constitutions were not shy about making their intentions known: Despite the vague language concerning “aliens ineligible for citizenship,” their main purpose was preventing the Japanese from settling within their states. Washington Democratic state representative Miller Freemen unabashedly proclaimed, “I have noticed the alarming situation by reason of the foothold that aliens, and especially Japanese, are acquiring our agricultural lands. For the purpose of prohibiting and stopping this evil I have drawn a measure which prevents aliens owning land.”38 The newer proposed laws, unlike the constitutional amendments, also laid out more specific language prohibiting business transactions between citizens and aliens ineligible for citizenship (and making those that already existed void), the inheritance of property by American-born children, and most importantly, the leasing of land. For Japanese who could not afford to purchase property outright or who were migrant farmers with dreams of eventually becoming property owners, renting farmland from larger planters was a way to make a decent living on the West Coast. West Coast politicians detested such opportunities and sought to prevent all classes of Japanese from seeking a new start in their states.39

California was at the helm of a legislative trend when the state legislature passed the Alien Land Law in 1913. Since there were still some legal and anthropological debates on whether or not Japanese could be classified as “whites,” the 1913 act went further than the amendment to the California constitution by mentioning specifically aliens who were ineligible for citizenship. The act prohibited noncitizens who could not naturalize from owning property and also from leasing land for longer than three years. The law did not prohibit the children of Japanese immigrants from owning property, however, prompting California citizens to fear that the act would not be effective. Although there was no legal or constitutional way to prohibit American citizens from owning property under the Fourteenth Amendment, the California legislature passed a new land law in 1920 that completely banned any lease agreement with ineligible aliens and required the sons and daughters of immigrants who held property to fill out yearly reports detailing their business activities. These measures were an attempt to undermine all Japanese American truck farming. The American Legion, anti-Asian associations, and various politicians along the West Coast and in other parts of the nation supported California’s measures and sought to bring similar legislation to fruition in other states. Washington passed its own alien land law in 1921, and Oregon followed in 1923. By the mid-1920s, Arizona, Arkansas, Idaho, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming had passed anti-alien land laws with language similar to that of California’s.40

It did not take long for some southern states to turn on Japanese Americans and pass their own versions of California’s law. Although the population of Japanese Americans in the South did not rapidly increase between the early 1900s, when many whites first welcomed the Japanese with open arms, and the later advent of alien land laws, Florida, Louisiana, Texas (the three states with the largest Japanese American colonization populations—153, 219, and 449, respectively), and Arkansas would either pass their own anti-Japanese legislation or, in a more dramatic measure, amend their constitutions to prohibit aliens from owning property. What had transpired in such a short period of time to make whites turn on their “little yellow brothers” who once held such promise? While each southern state had its own problems with Japanese Americans living within it, an imagined fear of Japanese invasion from the West Coast fueled more reactionary measures from state legislators and southern citizens.

There were Louisianans who warned of the impending doom arriving in the form of the Japanese well before the rise of anti-alien land laws. In 1906, a group of 200 Japanese families purchased land for growing rice in Crowley, today the “Rice Capital of the World.” Although most of the local businessmen and residents supported the colony, some residents watched what they saw as an unabashed embrace of an “Oriental Host of Mongolian cheap labor” from afar.41 Rather than see Japanese Americans as motivated entrepreneurs, some in Crowley saw them for what they believed the immigrants really were: “pauper hoards” who were only shipped into Louisiana to benefit a “few large landholders who will be enabled to dispose of a little more land, or farm a little more with this form of cheap labor.”42 An article published in the Rice Belt Journal touched briefly on common themes of racial difference between Japanese Americans and “caucasians,” wondering why Louisianans should view the Japanese so differently from the Chinese when the basic problem was the same—“Japanese can never be amalgamated.”43 But the bulk of the author’s displeasure with his community’s welcoming of the Japanese settlers rested with their inability to see that “Japanese immigration . . . will swell the hords [sic] of cheap labor with which our country is already burdened” and “add to the overproduction of our great staple crop [rice].” This was a direct rebuttal to those who sang the praises of Japanese Americans as a vehicle for economic growth and crop diversification. Ultimately, Japanese immigrants would be responsible for placing “the American farmer on the same plane as the Oriental” and “add[ing] a new element of complication to our social problem, cheap labor, and debas[ing] the high standards of American living.”44 These were early warnings of a potential flood of Japanese Americans who would arrive in Louisiana and drastically alter the social, racial, and economic order of the state in disastrous and terrifying ways. “Louisiana already has one race problem,” one resident explained in the New Iberia Enterprise, “which presents itself everyday of the year and which is ever a costly one in many respects—to introduce a yellow peril . . . would be [to] court disaster, to offer a premium of annoyances of every sort, to invite trouble as a permanent guest for future years.”45 How could inviting more “yellow” Japanese Americans into the state possibly simplify the existing “race problem” between whites and blacks?

The author was begging his or her neighbors to understand that “California’s experience with its Oriental problem should be an object lesson, sufficiently convincing to protest any other white community from encouraging the presence of Japanese in numbers, however small.”46 There was the key to how this resident and others in Louisiana and across the South would come to view the presence of Japanese Americans in their states. No matter the size of the existing Japanese American population, be it 5 or 500, Japanese Americans challenged the order and structure of southern life. This was not a matter of numbers but, rather, a fear of what Japanese Americans could do. Plus, there was always the possibility that even the smallest number of successful and profitable Japanese Americans would attract more to Louisiana from California. “The press and people must unite in insisting that no Japs are wanted in LA, for as badly as the state needs development, it were better that its farms should become a garden of nettles, its swamps remain unclaimed and its virgin forests un-cleared [than] that a foothold be given within its borders to this pestiferous people who can only be compared with ants—undeviatingly a pest wherever they appear,” one resident from Shreveport declared.47 Like blight, Japanese Americans would sweep into Louisiana and destroy whites’ economic basis for survival. Another author from St. Tammany Parish near Baton Rouge bemoaned the continued support of the Japanese, arguing that “ if these lands are so valuable and so productive, then surely they must soon be settled by capable and energetic farmers of the white race.”48 “If Louisiana fills her land with Japanese, which she ultimately will do if this colonizing is allowed to get a foothold,” the author warned, “she will dig her grave politically and shut herself off from the prosperous states of the Union. . . . Drudgery, cheap labor, and hoarded slaves will never help us.”49 The ability of Japanese Americans to damage economic relations with other states was a grave prediction and reflected the fears of what effect the colonizers would have on Louisiana and southern society.

In 1913, James Taylor, a real estate agent from the Natchez sugar district, submitted an article to the aptly named Caucasian that ignited a push for legislative action in Louisiana to prevent Japanese American settlement. In “The Japs Invasion,” Taylor, who sold land to “white farmers only,” gathered information from rumors and his own discussions with other landowners and real estate agents and compiled a report that he submitted to the Caucasian. Taylor warned that with other real estate agents willingly entering into agreements with Japanese colonists and a “tide of Japanese immigration” coming to Louisiana as a result of the California laws, white Louisianans may be forced to sell their land at cutthroat prices to escape the “menace,” a form of white-planter flight. Taylor surmised that with its “fertile lands” and cheap prices, “Louisiana is the natural field to which those people might turn following the laws excluding them from owning land in California.”50 As a real estate agent, Taylor was well informed to report that when Louisiana attracted enough Japanese, citizens would see a fate similar to that of California: “When the Japanese farmers move in, American farmers move out.” Because “Americans have no neighborly feelings for Japs,” they flee to other areas, and as a result, land prices become depressed.51 Taylor freely admitted that “Southern people are, by nature and environment, reared with the feeling of aversion for races of a different color; and any encroachment by outsiders who are regarded undesirable for this reason is quickly resented by them.”52 Japanese immigrants had learned a valuable less in California that if they settled in greater numbers near whites, the whites would flee, giving Japanese Americans access to cheap land and resources. “High prices will not keep the Jap out of Louisiana,” Taylor warned readers. California’s history might well be repeated in Louisiana unless “the real estate men . . . take some steps to meet and forestall any conditions that would result form an influx of Japanese into this state” or if the Louisiana legislature passed an act similar to California’s.53

Debates over whether or not to oppose Japanese American colonization diminished in the Louisiana press and among residents during World War I, when Japan allied with Britain, France, and Russia and general war troubles pervaded the country, but reached a fever pitch again in 1921. A year earlier, California amended its earlier anti-alien land law to prohibit the leasing of land in addition to ownership for aliens ineligible for citizenship. Although residents in Louisiana’s rice belt, where most Japanese Americans settled, were generally welcoming, those in the northern part of the state near Arkansas worried that if they didn’t follow California’s lead, they might be faced with the type of problem that Taylor had described. What Louisiana desperately needed was its own anti-alien land law, and Jonathan S. Dykes, a furniture store owner in Union Parish who also had businesses and cotton land in Arkansas, became the voice of those who held similar views. In 1920, Dykes advocated among local business owners in northern Louisiana for an anti-alien land law to safeguard against the settlement of refugee Japanese in his state. The strongest supporters of such a law were the cotton planters who straddled the borders of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas and feared Japanese Americans leaving the rice belt and settling in cotton country. Considering Taylor’s dire warnings, there were concerns that this may be the case if whites fled the land and Japanese Americans gained more power.

The push for anti-alien land legislation in Louisiana revealed an interesting and complex view of Japanese Americans in the South. Although words of anti-Japanese sentiment filled local newspapers in the state, land laws became a form of political opportunism that would benefit mainly farmers and landowners from specific agricultural industries such as cotton or rice. The relationship of Louisianans to their idea of the Japanese—created from negative media portrayals and generalized Orientalist stereotypes—was often different from their relationship to the Japanese Americans within their state, who were brought to help rebuild agriculture and the economy. On the ground, no actions were taken in the southern rice colonies of the state to drive out Japanese (despite boisterous claims from some newspapers), while in the north, where cotton was king, those invested in the crop spoke the loudest against potential Japanese Americans moving into their industry.

Fortunately for Dykes, his opportunity to prevent Japanese encroachment on Louisiana territory came later in 1921 when Louisiana held a constitutional convention in Baton Rouge. Following World War I, questions of taxation, minimum wages for women and children, the relationship between the burgeoning oil industry and the state, and the parish system of local government begged attention from both citizens and the legislature. More importantly, many argued that the most current constitution from 1913 was still too heavily influenced by the constitution from 1879, which was ratified during the days of tumultuous Reconstruction and considered a product of carpetbagger malfeasance.54 Under Louisiana law, a constitutional convention cannot be called by the state legislature unless the question of whether or not one is needed is put up to public vote. Governor John Parker proposed the idea of a convention to the people in November 1920, and they approved. The residents of Union County voted for Dykes to represent their interests at the convention, and the newly elected delegate was more than eager to serve. By the time the convention delegates descended on Baton Rouge in March 1921 to begin their work, there were a variety of committees and topics, including those mentioned above as well as income tax rates and the election of legislative representatives. Not mentioned was any sort of restriction on alien landownership, but Dykes went into the convention with this goal in mind.55

On March 22, a few weeks into the convention, Dykes—who served on the Committee on Co-Ordination—introduced Ordinance 245, a motion to amend Article I, Section 4, to prohibit Japanese immigrants from owning property. Knowing that despite cultural and social anti-Asian sentiment there was not overwhelming support statewide to create an anti-alien act, Dykes worked with William Chappius—an opponent of Japanese settlement from the Acadia Parish—to create an anti-alien amendment to the constitution. Such a measure would be a strong statement that the constitution of Louisiana did not recognize Japanese as deserving of property rights and the civil rights that accompanied them. In effect, any change to Article I, the basic bill of rights, would change the way the state defined general rights and state citizens. While the article previously did not mention aliens or citizenship in relation to property rights, Dykes’s amendment read, “No alien who is ineligible for citizenship of the United States or of the State of Louisiana shall be permitted or allowed to acquire or own, directly or indirectly, in his or her name, or by means of any kind or character whatsoever within The State of Louisiana.” Similar to the anti-alien laws of West Coast states, the vague mention of “aliens ineligible for citizenship” could technically have included other groups for criminal or medical purposes, but the intention was clear: to discourage Japanese from settling in Louisiana. Asians were the only racial group that could not naturalize at this time.56

Discussions on other matters consumed much of the convention delegates’ time and energy between March and the late spring, but the anti-alien amendment did not go away. Walter Burke, a Democratic representative from Iberia Parish and an attorney with a progressive streak, served on the Committee for Co-Ordination with Dykes but was far more interested in his own ordinances on education and employer liability. Burke grew weary of Dykes’s attempts to redirect attention away from Burke’s needs and urged other committee members to be more specific about the proposed target of the amendment. On June 14, Burke proposed more specific language in the proposed amendment. “If it was the intention of the Convention,” Burke began, “to exclude from the right of ownership of property any alien who, because of personal and particular reasons, may be ineligible for citizenship in common with those excluded as a class as for example a European, who, because of his mental ailment, or because of his doctrine upon government might not be admissible to citizenship, then there is no suggestion to offer.” However, “if it was the intention to exclude those because of race or nationality are ineligible, then the suggestion made that the ordinance be amended by inserting . . . ‘by reason of race or nationality.’” If the point was to exclude Japanese and other Asians from owning property in the state, as Dykes had so clearly stated in the press and in personal conversations many times before, then the amendment should reflect this in order to avoid bureaucratic confusion. Burke’s suggestion would have made the amendment different from some of the other anti-alien land acts by mentioning race and nationality specifically. Eventually, the convention voted to table the discussion of Burke’s suggestion, but it represented a moment when the discussions of race, nationality, and immigration were brought to bear directly on Louisiana’s constitution.57

Ultimately, Dykes’s ordinance was approved by a majority of the delegates of the convention, and the amendment was placed in the new constitution. The general attitude of citizens toward their most recent governing document was not one of jubilant approval but one of weariness and suspicion. The convention lasted nearly five months, prompting many to worry about the tax dollars being wasted. Also, the legislators had to defend the convention against “rumors that the convention was merely a puppet of Standard Oil to dictate a severance tax law,” rather than an attempt to revamp the constitution.58 The biggest controversies of the convention for the average Louisiana citizen were the possibility of turning the parish governing system into a county system and the fact that the delegates decided in May that French would no longer be used in conventions.59 When all was said and done, 802 amendments were proposed by delegates; 536 were ultimately approved in an up-down vote, including Dykes’s. The anti-alien amendment went under Article XIX (General Provisions), Section 21. It not only prohibited aliens ineligible for citizenship from owning property in a variety of forms, including leasing and receiving land through inheritances, but it also gave the Louisiana legislature the power to create any additional laws as needed to support the amendment. The Donaldson Chief explained to readers that “this article is in line with the law of California . . . and is intended to prevent all Asians who are not eligible for citizenship of this country from owning any land in the state.”60 Because the legislature was not required to submit the new constitution to the people (as the delegates were elected by the people), it was adopted on June 18, 1921, by the convention and became the law of the land for the next five decades.61

The overwhelming details and amendments to the constitution allowed the anti-alien amendment to be somewhat overlooked by the public. In the press, there were few reactions to the new amendment apart from articles explaining how it was similar to California’s and that, yes, it did specifically target Japanese Americans. Even Louisianans who opposed Japanese settlement in their state were relatively quiet. Talk of Japanese Americans in newspapers went from discussions of agriculture and colonization to American and Japanese diplomatic relations and arms negotiations. The amendment to Louisiana’s constitution pertaining to land, a significant change in property rights, the application of the Fourteenth Amendment, and conceptions of citizenship went largely unnoticed by the populace. Without the need for public approval, Dykes and those northern landholders as well as those in the southern part of the state who supported him received what they had been searching for. The presence of small communities of Japanese Americans and the politics of a few planters shaped the constitution, while Japanese Americans and their interstitial status continued to puzzle Louisianans and create a mix of reactions to the amendment across the state.

The place of Japanese Americans living in Louisiana well before the amended constitution took effect was uncertain. There was no massive backlash against Japanese Americans following the amendment as there was in California after the enactment of its alien land law. Also, it was not clear if the amendment would be retroactive and Japanese Americans who had purchased land before the new constitution would lose their property. Despite the new restrictions, many Japanese Americans continued to live in Louisiana on the land they had previously purchased, or they migrated to New Orleans for new employment opportunities. Like so many Jim Crow laws across the South that were amorphous to a degree that maneuverability was possible, the new Louisiana constitution was vague on how it applied to Japanese Americans and others. The fact that Dykes and others like him so feared even the smallest number of Japanese Americans in their state that they were able to alter the constitution was an impressive feat that reflected the South’s fear of Asian immigrants, a new racial minority that Louisianans were unsure of.

Despite the initial welcome of Japanese in various parts of the state, by 1912 the same anti-Japanese attitudes that swept through Louisiana also made their way to Florida. Many of the negative descriptions of Japanese Americans were similar to those that originated elsewhere and reflected a growing concern that more Japanese migrants would arrive from the West Coast. According to southerners, their land was a waiting bounty for the ruthless Japanese looking to steal it from white citizens. Almost overnight, the same characteristics of Japanese Americans that many admired became their faults. Japanese Americans went from being “fine farmers” with “agricultural methods that will be a desirable object lesson to their white neighbors” to “ferocious and land hungry” people with no desire to assimilate or discard their “clannish” ways. “In small numbers,” an Ocala Evening Star editorial warned in 1913, “they constitute no menace, but a thin stream of them trickling into Florida, lured by the success of those now here, might in time swell to a volume that would gives us more Japanese than we needed . . . another California problem.”62 Although President William Howard Taft attempted to “smash the bugaboo of Japanese invasion” in an address given in 1912 by explaining that “there has never been any intention on the part of Japan to attempt to gain a foothold in North America,” this did little to assuage a growing number of Floridians who believed that the few Japanese Americans in their state could potentially turn into multitudes.63 Whereas hardworking Japanese immigrants were once seen as a way to make Florida prosper, now that same work ethic rendered them undesirable.

In addition to blaming the land-hungry and ferocious Japanese immigrants coming from the West Coast for supposed increased competition for land, some Floridians turned their ire toward politicians and leaders for importing competition and cheap labor. In 1913, a group of Japanese horticulturists arrived in Jacksonville “direct from California” to strike up a deal with real estate agents for swampy, unwanted land in Clay County closer to Gainesville than the coast. However, when the Ocala Evening Star editors learned of the proposed deal, they lashed out at the “undesirable immigrants” as well as Governor William Sherman Jennings, whom they accused of engaging in underhanded deals in order to recruit Japanese migrants to help Florida compete with the California citrus growers.64 In Jacksonville, the president of the Chamber of Commerce incensed one resident with a speech openly urging Japanese Americans to settle in Florida. “Just why the businessmen of Jacksonville would import cheap heathen labor to compete with the white farmers and growers of Florida is not plain to us . . . when there are thousands of honest, hard-working white men north of Florida who can be induced to settle in Florida and help develop it.”65 Although “cheap labor may be alright for corporations,” it did not sit well with the author. Now Japanese Americans were not only threats to landownership but also threats to the general well-being of all Floridians. The article ended with a rousing call for the farmers and fruit growers of Florida to “join the AFL in asking Congress to exclude Japanese immigrants, the same as it does the Chinese.”66

An author known only as “The Korokan” also responded negatively to Garner’s Chamber of Commerce speech by discussing the devastating impact that further Japanese colonization would have on race relations in Florida. Speaking as a “seasoned traveller” with extensive knowledge of Japanese behavior, The Korokan argued that because “Japanese women keep having babies” (which was also the cause of the Russo-Japanese War and a “scientific and cultural fact”) and the “islands of Japan are not big enough to hold the Japanese people . . . they must go somewhere.” Should that somewhere be Florida? Although there were already Japanese in the state and “Florida is a cosmopolitan state whose arms are extended to welcome the peoples of the earth . . . the line ought to be drawn somewhere.” Floridians were already forced to contend with the “colored man,” but the Japanese were a different kind of colored. A black man was like an “old, faithful dog” who had adapted to the Jim Crow laws of the South, while the Japanese were “a serpent—subtle, scheming . . . and conscious-less [sic].” If Floridians were to “harbor any colored race, let it be the black man,” for at least the black man was innately subservient and generally harmless. The Korokan couldn’t fathom why businessmen in Jacksonville would be willing to “throw open our gates to another colored race” when the South was still reeling from Reconstruction. “It is strange, but nevertheless true that we never seem to take warning from the plain lesson of history,” The Korokan ruminated. The Japanese, though “his civilization [is] higher, his business instincts sharper, and his skin a shade lighter” than an African American’s, would only invite more racial turmoil into the state. If Japanese colonization was encouraged in Florida, The Korokan feared that the state would be overrun with Japanese, displacing African Americans and creating a far worse racial scenario. “Let Florida beware the yellow peril,” The Korokan grimly warned before concluding his dark and gloomy prediction of the Sunshine State’s future.67

Florida Democratic representative Frank Clark spearheaded the anti-alien land law movement in his state. Clark, a former district attorney and representative in the state legislature for Jacksonville, was a U.S. representative by the time he began to speak out against Japanese colonization in his state. Well before Japanese Americans arrived, however, Clark had gained a reputation in Florida and throughout the South for his passionate devotion to white purity and Jim Crow. In 1911, Clark proposed a bill before the House of Representatives prohibiting marriages between whites and blacks in Washington, D.C. The bill never passed, but Clark’s reputation as a staunch segregationist benefited. Clark’s views on the Japanese in his state were relatively subdued before 1913. He shared his time between two homes, one in Jacksonville and one in Gainesville, both near Japanese American settlements. Clark was undoubtedly aware of the presence of Japanese Americans but never publicly took up the crusade against them in the early 1900s. By 1913, however, Clark suddenly became a leader in the state’s growing anti-Japanese movement, which was particularly strong in the northern and central counties, far from where the Japanese American colonies were actually located. Some of Clark’s critics wondered if his sudden interest in the Japanese problem was merely a ploy to win reelection as representative, but others admired, as one Fort Meyers resident did, his ability to “bravely stand up and object to colonization by other than white people . . . . We are with him on the side of the race or immigration problem.”68 Clark exclaimed his passionate anti-Japanese hatred in the press during the summer and fall of 1913 and held up California’s alien land law as an example of what should be done in Florida.

In October 1913, Clark issued a statement to the press that would link his name to the Japanese debate. Clark explained that he was “outraged that the proposition for more Japanese colonization did not receive more attention” and stated firmly that “Florida must always be a white man’s country and we cannot preserve our civilization if we propose to allow Japanese, Chinese or other races with whom the Caucasians cannot assimilate to become landowners and citizens in our midst.”69 Clark had other backers, including Mayor Van C. Swearingen of Jacksonville, who had earlier proclaimed, “I know nothing of the Japanese personally, but it would seem from all reports that they have not been acceptable to people on the Pacific Coast” and, with the assistance of the Florida Southern Settlement and Development Organization, advocated for bringing white settlers from Europe and the North to the state instead.70 Democratic representative from Jacksonville Claude L’Engle also agreed with Clark’s views on the Japanese, explaining that “the Japanese are incapable of being assimilated with Caucasian civilization and as laborers cannot be handled tractably like the whites.”71

The idea of a law that would prevent Japanese Americans from settling in Florida gained support throughout 1913. If California could do it, why couldn’t Florida? That was a question easier asked than answered. Clark proposed that perhaps the best way to solve the problem with “the little brown people” was to “institute . . . the enactment of a law by the next legislature of Florida that will forever prohibit the Japanese, or other races which cannot assimilate with the white race, from owning lands within the boundary of our commonwealth.”72 The idea of an anti-alien land law appealed to many of Clark’s followers, and Governor Park Trammell assured Clark that he would “investigate” the matter of Japanese colonization further to see if there were any underhanded deals or a few individuals getting wealthy by exploiting either the Japanese themselves or the land.73 Clark grew weary of waiting for Trammel’s reports and instead pressured the governor for an extra legislative session in the fall of 1913 to pass an act that would “prevent Asiatics from owning land in Florida.” Trammel listened to Clark’s request but explained that “there would be no extra session” because under the present state constitution, the Japanese “have the same right to colonize and acquire property in Florida that is guaranteed to the most favored foreigners” and Florida citizens.74 Constitutionally speaking, passing such a piece of legislation would be illegal. While Trammel and Clark sparred over the constitutionality of the extra session, the push for an anti-alien land law lay dormant during World War I.

The anti-Japanese feelings emerged again, however, when more speculators became interested in developing and selling Florida land during the 1920s. With the addition of more railroads and better highways as well as the proliferation of the automobile after Henry Ford’s efficient mechanization, investors saw great potential in Florida as a haven for tourists. Many wealthy visitors already vacationed in areas near Palm Beach and Boca Raton during the fall and winter to escape the harsh winters of the North, but the affordability of the automobile opened Florida to more tourists who might seek refuge in the Sunshine State. The undeveloped land near the coast offered opportunities to clear out scrub or stabilize marshy swamps to build vacation homes or sites of industry and farming. The development of Florida became one of the largest speculation opportunities during the 1920s as land was cheap and plentiful. There was a general belief that Florida, with its favorable climate and excellent growing conditions, would be the new miracle story of the twentieth century.75

With the increase of interest in Florida land, the desire to prevent Japanese American settlement peaked. Although Congress had passed the Immigration Act of 1924, which finally included the Japanese in the group of Asians excluded from migrating to the United States, by 1925 this did little to quell concerns among northern and central Florida farmers, property owners, and laborers that Japanese Americans would come in large numbers to their state. Suddenly, Clark’s call for an exclusionary land law seemed more fitting. Although Clark was out of office by this point and practicing law in Miami, there was a growing movement for an exclusion act at the state level in Leon County (where Tallahassee, the state capitol, is located) and in central Florida near present-day Orlando. Representatives Robert Davis (D-Leon) and Timothy Mackenzie (D-Lake County in central Florida) were acolytes of Clark and firmly believed that an anti-alien land law was the best way to prevent Japanese Americans from seeking refuge in Florida following the new acts along the West Coast. Rather than attempt to pass a piece of legislation that might not have enough support, Davis and Mackenzie decided to propose an amendment to the state constitution to prohibit aliens ineligible for citizenship from owning property, taking a cue from Louisiana. Davis and Mackenzie believed that the amendment should be proposed to the public, because the chances of them voting for it would be greater than the chances of passing a bill in the state legislature.

During the 1925 legislative session, Davis and Mackenzie proposed Joint Resolution 750 to amend Section 18 of the constitution to formally exclude Japanese from owning property. Other resolutions, including one for county school funding and the appointment of Supreme Court justices, were more hotly contested, but resolution 750 became one of the legacies of the June 1925 legislative session in shaping the constitution and the state’s official views of Asian immigrants. The amendment that Davis and Mackenzie sponsored, however, was different from that of Louisiana’s. Section 18 of the Florida constitution, or the Declaration of Rights, dealt with property rights and stated, “Foreigners shall have the same rights as to the ownership, inheritance and disposition of property in this State as citizens of the State.” This was a generous statement (only Arkansas’s constitution had a more direct clause granting property rights to noncitizens), one that was, according to Davis and Mackenzie, a bit too generous. On June 3, 1925, the two representatives proposed that Section 18 be amended to read, “Foreigners who are eligible to become citizens of the United States under the provisions of the laws and treaties of the United States shall have the same rights as to the ownership, inheritance and disposition of property in the State as citizens of the State, but the Legislature shall have power to limit, regulate and prohibit the ownership, inheritance, disposition, possession and enjoyment of real estate in the State of Florida by foreigners who are not eligible to become citizens of the United States under the provisions of the laws and treaties of the United States.” This amendment broadcasted Florida’s welcoming of white immigrants rather than the Japanese to help settle the land. However, the “aliens ineligible for citizenship” clause that was prevalent in the anti-alien land acts made its way into the closing sentences of the proposition. Were foreigners who were ineligible to become citizens barred from owning property through the amendment? Not technically, but the message was clear, and the proposed amendment gave the Florida legislature the right to pass any legislation it deemed necessary to stem the tide of Japanese colonization and settlement.76

On June 8, 1925, Davis, Mackenzie, and by virtue of association, Clark received what they had hoped for: The house passed the proposed amendment without a single “nay.” The fact that not one representative opposed the amendment speaks to the sense of complacency in many states surrounding amendments or proposed legislation to prevent Japanese and other Asians from settling and owning property. Such measures might be necessary to preserve resources and protect citizens, and surely, if other states were engaging in these practices, then far be it from Florida to run the risk of absorbing the fleeing Japanese. As in Louisiana, the fears of a specific group of Floridians over the small population of Japanese shaped the constitutional definition of citizenship and land rights. The senate approved the amendment a few weeks later and placed it on the ballot for the people to vote on in the 1926 elections.

The new amendment did not receive much attention from the general public. The few papers that did cover the amendment expressed confusion over what it was meant to accomplish. The Miami Herald editors expressed dissatisfaction, describing it as “constitutional tinkering” and unable “to accomplish any good.” “Nobody knows at just what class of people this amendment is aimed at. In all probability, it is intended to exclude Japanese from ownership of land in Florida,” the editors explained, adding that “if that is all there is to be accomplished by this solemn measure, it is almost foolish to ask the people of Florida to give it consideration.” The number of Japanese Americans in the state was “negligible,” and “there is not the slightest ground for the belief that a single Japanese will ever be barred by the amendment if it should become law.”77 Similarly, G. B. Wells from Plant City, Florida, wrote to the Tampa Times expressing his displeasure with the proposition. Wells feared that “the adoption of such an amendment will not remedy any existing evil . . . and if it is adopted it may be the opening wedge for more far-reaching amendments to come later” that might further restrict property rights for others.78 The only “favorable” reports of the amendment came from the Jacksonville and Tallahassee newspapers and merely described the proposed amendment.