Vietnamese Americans and Human Rights in Texas

On an overcast March afternoon, members of the Texas Knights of the Ku Klux Klan cruised the Trinity Bay near Seabrook (a small fishing town approximately half an hour south of Houston) on small fishing vessels as part of a “parade.” Brandishing guns and effigies of minority fishermen who were creating competition for locals, the Klan sent a clear message: The Galveston Bay belonged to whites and whites alone. Locals suspected the Klan had made good on these threats already, with the burnt-out skeletons of minority-owned buildings and fishing boats in the area serving as a testimonial to white power. The Klan stood for the rights of white fishermen in Texas and sought to reclaim the bay area from minorities the only way they knew how, “with blood.” It was an event that shared characteristics with other Klan demonstrations of threats and white supremacy throughout the southern states following the Civil War. White southerners’ ways of life were under attack by unwanted racial minorities searching for new opportunities in Texas, and the Klan’s tried-and-true tactics of violence and intimidation would not fail them now.1

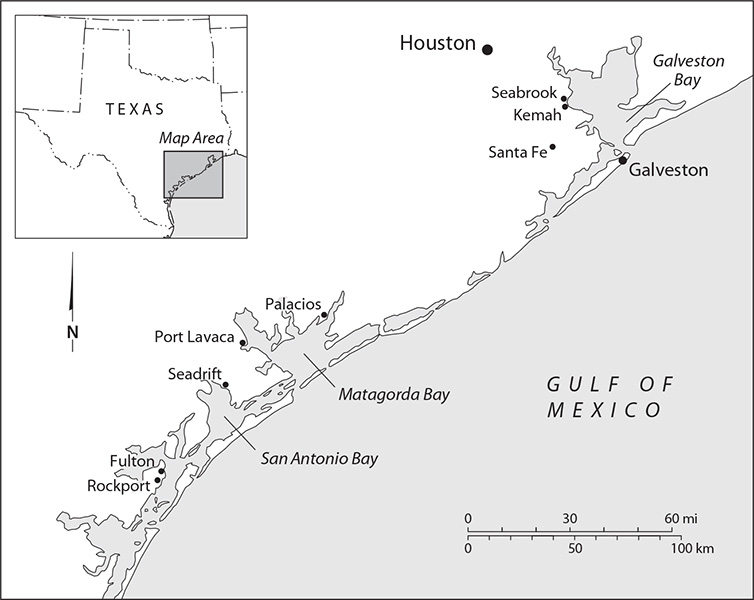

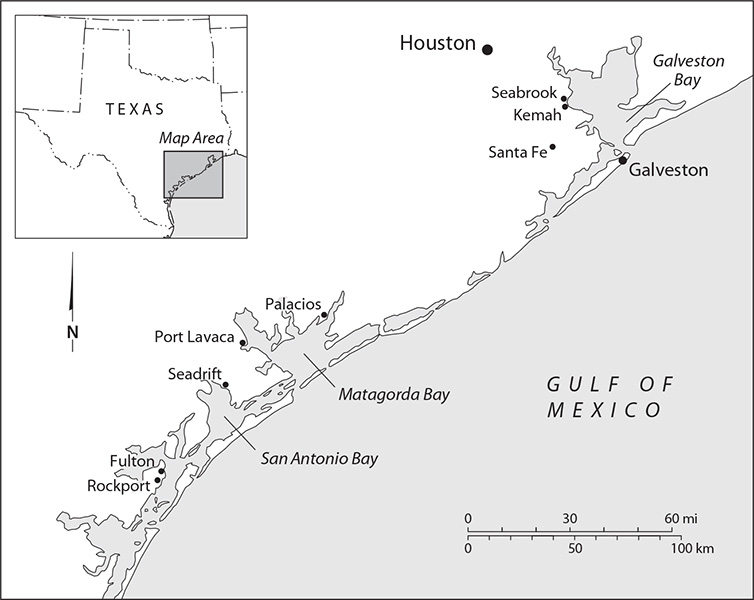

But this Klan demonstration occurred in 1981, not 1881, and Vietnamese American fishermen, rather than African Americans, were the target of the Texas Klan in Galveston. Time stood still in the Galveston Bay area when it came to racial relations and the role of the Klan in local affairs. The gains of the civil rights movement had in no way ameliorated the terrorist organization’s hatred of racial and ethnic minorities. The Klan’s intimidation of the Vietnamese American fishermen stemmed from the anger of some of the local white fishermen over the newly arrived immigrants and their “hogging” of the shrimp and crab catches. Following American withdrawal from the long, costly, and demoralizing war in Vietnam, Vietnamese refugees arrived in the United States seeking resettlement and an opportunity to rebuild their lives with the assistance of the U.S. government and various social and religious organizations, such as Catholic parishes, across the country. Many working to resettle the refugees believed Vietnamese to be natural fishermen and encouraged them to seek sponsors or find employment opportunities in the Gulf Coast fishing industries in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. By the late 1970s, several hundred Vietnamese settled in the Galveston Bay area of Texas near Houston and built small family fishing enterprises, pooling their resources to buy boats and other materials. To the dismay of local white fisherman, many of the Vietnamese experienced initial success in shrimping or crabbing in Galveston Bay or San Antonio Bay. Fear of competition in the already tight fishing industry, a severe economic downturn nationwide and resulting recession, racial tensions, a general distrust of the Vietnamese “enemy,” and harsh memories of the Vietnam War shaped the responses of locals to the Vietnamese refugees. Clashes between Vietnamese Americans and the locals were immortalized in a Bruce Springsteen song, “Galveston Bay,” as well as the 1985 film Alamo Bay, starring Ed Harris as a white fisherman and Vietnam War veteran coming to terms with both his past and the Vietnamese refugees who settled in his town. It was a classic Reconstructionesque story with a new spin.2

The involvement of the local chapters of the Klan, however, moved the interactions between the Vietnamese and a number of local white fishermen into the courts in 1981 with the Vietnamese Fishermen’s Association v. The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan case. Many suspected that Louis Beam, the Grand Dragon of the Texas Klan, and other members of the organization were behind the burning of several Vietnamese boats in Seabrook and Kemah (two fishing towns near Houston) and the firebombing of a Vietnamese home in Seabrook in February 1981. While Beam was never charged or convicted in any of these violent events, his unabashed use of intimidation prompted the Vietnamese Fishermen’s Association (VFA) (a group dedicated to representing the Vietnamese in the area) to enlist the help of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) in filing a civil rights case at a U.S. district court in Houston. The VFA sought an injunction against the Klan before the beginning of the 1981 fishing season in May for protection from violence and threats to their property and their lives. The trial began in 1981 and received national media attention, largely thanks to Beam’s incendiary remarks and dramatic behavior inside and outside the courtroom.3

Fishermen’s Association v. Klan was a watershed moment for civil rights, human rights, and immigrant rights as the three merged together in one case. Not only were civil rights battles far from over in the South after the landmark Supreme Court decisions and legislation of the 1950s and 1960s, but the struggle for civil rights merged with the struggle for refugee rights as the South became more diverse during the late twentieth century. A close legal analysis of the Fishermen case reveals that Vietnamese Americans used the courts not only to protect their property as other Asian Americans had done in the South before them but also to fight for their basic human rights to protection and safety. They called upon their status as refugees who fled Vietnam in search of the American Dream and safety to bolster their battles against the Klan, similar to other Asian Americans who often relied upon their noncitizen status in the courtroom. However, unlike Chinese Americans or Filipino Americans before them, Vietnamese Americans argued for the rights of refugees more generally rather than just Vietnamese refugees or members of the VFA. Also, the struggles of Vietnamese Americans were the result of both their unique identity as refugees and their racialization through the actions of the Klan and other whites in Texas. In turn, their identity shaped their legal strategies, which often relied on appealing to existing codes protecting property and commerce rights as much as refugee rights as they navigated the new terrain of refugee legislation. In many ways, the rights of refugees were up for interpretation, and Vietnamese Americans attempted to take advantage of the fuzziness of refugee status in court with mixed results. During the late 1970s through the early 1980s, the new immigrant Vietnamese clashed with the Old South that never died in Texas, resulting in a landmark stand for rights.

In addition to the Immigration Act of 1965, the Vietnam War also brought a new group of migrants to America and the South that challenged the model minority myth and created new interracial relations between whites and Asian Americans. When Americans withdrew from the war in Vietnam in 1973, chaos and terror soon followed for the South Vietnamese people. Fighting between North and South Vietnamese continued until the People’s Army of Vietnam and the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam captured the southern capital of Saigon in April 1975, causing the city to “fall” and many of its inhabitants to flee. Operation Frequent Wind, a plan to evacuate first Americans and, later, Vietnamese via helicopters, planes, and ships, produced iconic images of Vietnamese refugees scrambling to leave the wreckage of Saigon and their uncertain future under the Communist regime. The earliest Vietnamese refugees were high-ranking servicemen, politicians, and other wealthier elite and highly educated individuals, who were assisted in migrating to the United States with the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1975 (signed by President Gerald Ford). Later, Americans watched thousands of poorer Vietnamese, or “boat people,” pile into ramshackle dinghies or commandeer smaller American vessels that remained after the war in order to flee Vietnam, Communist reeducation camps, famine, and poverty. The Vietnamese who managed to escape joined other refugees, including the Hmong people and Laotians in refugee camps in Thailand, Guam, and the Philippines. The future of the refugees once they arrived at the camps was uncertain and often frightening.4

The plight of the boat people prompted President Jimmy Carter and Congress to create a federal program to assist refugees in 1980. Although the Vietnamese government established the Orderly Departure Program in 1979 under the guidance of the United Nations to assist persons seeking to reunite with family members, Carter and humanitarians who believed that America should do more to assist those who aided the American effort in Vietnam and the Cold War more generally supported using federal aid to help refugees resettle in the United States. The Refugee Act allowed Carter to make exceptions for refugees in the Immigration Act of 1965 visa quotas and established a uniform system for resettlement in the United States overseen by the State Department and the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and assisted by religious and charitable organizations. Once brought from the camps in the Philippines and Thailand, refugees were initially placed in refugee camps across the United States, including Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania, Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, Eglin Air Force Base in Florida, and Camp Pendleton in California. From there, social service agencies and religious organizations worked to secure sponsors for refugees so that they could leave the camps. Sponsors could be potential employers, churches (particularly Catholic churches, as Catholicism had deep roots in previously French Indochina), individuals, or recently resettled family members or friends. Although social workers and agents encouraged individuals or organizations to sponsor refugees, the resettlement program aimed to ensure that Vietnamese refugees would not overwhelm urban areas or create ethnic enclaves that would be isolated through language and cultural barriers and possibly create ethnic and racial tensions and job competition. As a result, refugees were directed toward sponsors in rural areas, including Minnesota, Michigan, Florida, inland California, and Pennsylvania. Once in their new permanent or temporary homes (depending on how long their sponsors committed to their needs and whether or not there were adequate, long-term employment opportunities), Vietnamese attempted to put their lives back together by obtaining employment, housing, and other basic needs with the assistance of their sponsors. The challenges the refugees faced in America, including language difficulties, poverty, discrimination, and mental health issues stemming from the stress and trauma of the Vietnam War, were overwhelming and tested the notion of successful Asian assimilation in America. Despite the challenges, by 1990, Vietnamese made up 8.9 percent of the Asian immigrant population in the United States; many were refugees or family members of refugees.5

Many social workers who assisted refugees often wrongfully assumed that most Vietnamese made their living from fishing in their homeland and sought sponsors from the Gulf of Mexico for their clients. Although the shrimp and crabbing industries along the Gulf in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Texas were not as robust as they once were by the 1970s and 1980s due to environmental threats to the native fish populations and state and federal attempts to regulate the hauls each season, social agencies believed that there would be opportunities for the refugees in the small, often more rural towns along the Gulf Coast. Some larger farmers and planters in these rural areas also attempted to use the Vietnamese refugees as cheap labor, in some instances as little more than slaves. One refugee, Kymberli Zamarripa, came to the United States as a young child during the 1980s and was sponsored by a woman from Macon, Georgia, who brought the Zamarripa family to her farm to work. Upon arriving, however, Kymberli and her family were paid nothing for their labor, forced to live in squalor, and threatened with violence if they attempted to leave. They eventually escaped and were able to make it to Palacios, Texas, with the assistance of other sponsors along the way, but there is no telling how many other refugees ended up in similar situations. Fortunately, social workers and agencies were often able to intercept and direct the refugees to legitimate sponsors around the Gulf Coast. In other instances, Catholic dioceses, like that in Austin, encouraged each Catholic parish to sponsor at least one family. By 1980, 80,264 Vietnamese lived in the South, concentrated mainly in Texas and the other Gulf states.6

Entering the fishing industry was not easy for the Vietnamese who settled in the Galveston Bay area of Texas, but for many, it became their way of life and shaped their experiences in the South. Many Vietnamese migrated with their families to Texas and pooled their resources once they were settled to purchase boats and other materials needed to shrimp or crab. Although, as one refugee explained, “a lot of these people [Vietnamese] when they came here . . . they [didn’t] have the fishing business background,” as many social workers believed, they still made a go at shrimping and learned the trade once they arrived in Texas.7 Hai Trong Nguyen, a refugee who fled from Vietnam by boat in 1976 with his brother, was a prime example of a Vietnamese settler in Texas. When Nguyen arrived in Palacios (a small town about an hour and a half west of Houston on the Matagorda Bay), he and his brother used their pooled resources to build a boat for shrimping. Once they established themselves in the fishing industry, they were able to send for other family members. In other cases, the children left the camps first and moved to Texas before bringing their families with them. Another typical case was that of Thé Nguyen Nasternak, who left Vietnam with her family in 1975 and came to Port Lavaca, Texas, in 1980 with the assistance of the Catholic church of Bloomfield, Michigan (her first stop in resettlement). Nasternak landed a job in a local restaurant and was able to purchase a trailer for her family to live in with savings and loans. After her family joined her in Port Lavaca, her father shrimped there for three years before the family moved on to another nearby Texas city where there were fewer fishermen.8 After a family achieved moderate success in shrimping or crabbing, they were often able to expand into other family-owned businesses such as restaurants and nail salons.9

Map of fishing towns in the Gulf of Mexico/Galveston Bay region of Texas where Vietnamese refugees settled.

Their success in shrimping, crabbing, and other enterprises encouraged many Vietnamese Americans to initially think of Texas and the United States more generally as places of boundless promise for refugees. Nghi Van Nguyen, a laundry owner in El Camp, Texas, who decided to try another business after he failed to make a good living in shrimping, described the United States as “a good country with opportunity for people who would come here” and “always thanked God Americans help[ed] us from the beginning.”10 Although only 36 percent of Americans supported the resettlement of Vietnamese refugees in America and those who did not cited overcrowding, employment competition, and a desire not to help “the enemy,” Thé Nguyen Nasternak “never experienced [prejudice]” and credited her family’s ability to “really work for everything we have” for getting in the good graces of the local populations.

Many Texans believed, however, that the Vietnamese refugees received extra help from the federal government and that their hard-earned tax dollars paid for Vietnamese boats and other fishing materials. At the time, white, working- and middle-class members of what Richard Nixon deemed the “Silent Majority” argued that their tax dollars supported the social and economic reform programs of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society plan, which provided no benefits to them but, rather, supported “moochers” and thankless racial minorities. The belief that the Vietnamese benefited from government assistance more than American citizens was closely related to larger negative perceptions of social safety nets. Nasternak and others understood this sentiment; she explained that her family was never on welfare but that “it’s hard because the working class of Americans . . . see certain situations where people are coming over and getting freebies and stuff—I understand if people experience certain prejudice.” Nasternak insisted that families who worked hard and worked together did not experience any prejudice from those around them because they proved that they did not depend on the government and were as diligent as Americans. Adopting the Protestant work ethic was a way for Vietnamese refugees to make a living as well as to adapt to American and southern life as racial minorities.11

But other reactions from Texans to the new Vietnamese reveal a different, more discriminatory, and more racially charged picture of Vietnamese settlement in the South. There was a potpourri of responses to the arrival of the Vietnamese in Texas, ranging from warm welcomes to reluctant tolerance to general xenophobia and blatant racism. However, the residents in the Gulf region of Texas provided specific economic reasons for their displeasure with the refugees. Whereas many Americans praised Asian Americans for their assumed work ethic, that same characteristic and stereotype made life difficult for the Vietnamese in the Texas fishing industry, proving that hard work and the model minority identity could only go so far. Many fishermen were struggling financially due to environmental and regulatory factors when the Vietnamese settled in Texas, adding extra challenges to an already highly competitive environment. Since the bay shrimp season ran from May to July of each year, there was a weight limit on how much shrimp fishermen could have on their boats.12 The middlemen who purchased the catches from the fishermen as well as the Coast Guard were charged with reporting and enforcing these limitations; but for decades, such enforcements were lax, and overfishing began to take its toll by the 1970s. Rather than focus their ire on irresponsible federal agencies that failed to regulate the industry, many Texas fishermen blamed the Vietnamese for their woes in the late 1970s and early 1980s, linking the depleted fishing grounds with the arrival of the Vietnamese immigrants. Fishermen in the bay imposed forms of self-regulation or “unofficial codes” of conduct that ensured that no one would infringe on another’s catch. Such measures included boundaries to prevent overcrowding in a good shrimping area and threats to report to officials anyone blatantly disobeying catch limits. Some of the earliest complaints made by fishermen against the Vietnamese were that they, according to a Seadrift city council woman and wife of a local fisherman, “pushed their way into the crabbing and shrimping industry with stubborn disrespect for local courtesy.”13 The Vietnamese allegedly placed their crab traps too close to those of other fishermen, but white fishermen also charged the Vietnamese with the illegal purchase and construction of boats to deliberately circumvent the catch limits.14 Although maritime laws prevented noncitizens from operating boats over a certain weight limit (five net tons of replacement), many fishermen interpreted this rarely enforced law to mean that noncitizens were not allowed to own any vessels regardless of their size.

While some Vietnamese did in fact own boats that were over the weight limit for noncitizens (as revealed by a later investigation by the Coast Guard in 1981), most Vietnamese purchased junk boats from local fishermen at prices far above what they were worth and refashioned them with the help of family and friends—a classic example of one man’s junk becoming another man’s treasure. As local fisherman and wholesaler Leslie “Lee” Casterline explained, when the Vietnamese started rebuilding the boats that were discarded by local fishermen and became competitive with the locals, “that’s where the problem started.”15 “Those American shrimpers sold their old junk boats to the Vietnamese figuring that they wouldn’t be able to make any money out of them. . . . Now the Vietnamese are building . . . them lighter, faster, and with better navigational aids.”16

Vietnamese American leaders attempted to explain that the roots of the problem were simple misunderstandings of the laws and cultural differences (Vietnamese worked as groups in the fishing industry, whereas the local fishermen took a more individualistic approach), but such explanations fell on deaf ears.17 In 1980, the residents of various bay towns and cities wrote the governor as well as other representatives asking them to intervene against the Vietnamese on their behalf. Concerned citizens of Rockport gathered in the Sacred Heart Parish hall to meet with their local representative and ask for help in “moving these people away from the coast . . . because they are overfishing [and] they don’t keep the rules of fishing.”18 Father Gregory Dean, who was placed in Rockport by the bishop after the Vietnamese population grew in the town, observed the meeting from the back of the hall, bemusedly listening to the locals “carry on.” Dean, who felt the congregation should “always have a soft spot in our hearts for an underdog,” became an ally of the Vietnamese in Rockport and challenged the townspeople in attendance at the meeting. When one of the concerned citizens demanded that all of the Vietnamese be arrested because they had broken the shrimping and crabbing rules, Dean retorted, “How about the people that sold those boats to the Vietnamese? Don’t you think you should arrest them as well if you’re going to go after the Vietnamese?”

Others around the bay demanded government intervention, which they received in early 1981 through a survey of boats by the Coast Guard and the Regional Parks and Wildlife Department commissioned by Governor Bill Clements. Unfortunately for the white fishermen, the survey “debunked yet another persistent, but apparently false claim” that the Vietnamese operated illegally large vessels. Not only did the survey find no evidence of Vietnamese wrongdoings; it also determined that the few boats that were larger than legal limits belonged to white fishermen. Carl Covert, the Wildlife Department director, believed that “this was all stirred up by that bunch down around Seabrook in an effort to get the Viet off the water.” There was little substance behind the claim that the Vietnamese were violating laws or even fishing customs, and the only motivating factors, according to the Houston Post, which reported on the issue, were “sour grapes” among the fishermen who were desperate to drive the Vietnamese out of town. But the Vietnamese were holding steady, or put more simply by Petty Officer Doug Bandos of the Coast Guard, who assisted with the survey, “You may burn these people [Vietnamese] once [by selling them junk boats], but you’re . . . damned not going to do it twice.”19

The local fishermen may have genuinely believed that the Vietnamese were violating laws and overfishing the bay, but there were more deep-seated reasons for why the Vietnamese received such a cold reception in Texas. Fear of competition from immigrants was a common trope in American history and had a long legacy in the South; however, an age-old distrust of racial others combined with more specific circumstances during the 1970s to create a unique situation on the Gulf Coast. Many of the local fishermen were also either veterans of the Vietnam War or friends and/or relatives of veterans who had fought and perhaps died overseas. Echoing similar experiences in towns and cities across the country and specifically where other Vietnamese refugees settled, locals who witnessed the Vietnam War either firsthand or through personal loss viewed the Vietnamese with not only suspicion but outright hatred. Racist reactions to outsiders combined with the fact that, as fishermen explained, the Vietnamese “looked the same” as the enemy in Vietnam, “and when you get geared that a person that looks like that has just killed your friend . . . you know you can’t block that out.”20 In this case, the racial history of the South melded with the negative legacies of the Vietnam War as well as an economic downturn created a perfect storm of interracial tensions. Anti-Vietnamese sentiment combined with the low levels of support for the refugee resettlement program in the United States added a xenophobic layer to the complications between the Vietnamese and the whites in Texas. The Vietnamese arrived at a time when both legal and illegal migration from Mexico was also on the rise following the Immigration Act of 1965 and social, economic, and political changes in Central and South America. Texans did not respond kindly to what they identified as another group of unwanted immigrants here to create labor competition or to “freeload” off the government. The Vietnamese did not possess an interstitial or a model minority identity in Texas; their racial and immigrant status cemented their reputations among the fishermen as “government moochers” and as yet another problem for the United States and Americans to deal with. Racism and xenophobia were couched in traditional anti-immigrant arguments that represented the South’s reactions to the changing ethnic and racial makeup of the United States after 1965.21

Racism bubbled beneath the surface of the tensions between the Vietnamese and the local fishermen until a violent encounter in Seadrift (about three hours southwest of Houston on the San Antonio Bay) between two young Vietnamese American men and a white shrimper brought the growing racial conflict to an explosive head in 1979. On Friday, August 3, two brothers and fishermen, Chinh Van Nguyen, twenty, and Sau Van Nguyen, twenty-one, were having a few drinks at a local watering hole where Rudy Aplin, a local fisherman, and his brother Billy, who was visiting from Florida, were also celebrating the end of a another workweek. There were conflicting accounts of how the two parties initially engaged (the Nguyen brothers claimed that Billy—“a big guy . . . a KKK member or something like that”—started the trouble by approaching them and threatening them with a knife, while Rudy insisted that the Vietnamese Americans instigated the trouble by “talking big” to Billy), but the incident quickly escalated from a macho barroom brawl to a violent and fatal encounter. Regardless of the particulars, Sau shot and killed Billy and later fled to Louisiana with his girlfriend Lisa, where police eventually arrested him in Port Arthur the following afternoon (Chinh was also arrested but was released on $75,000 bail paid by his family and friends).22

Although Billy Aplin’s murder at first appeared to be the result of an unfortunate encounter, more information emerged that revealed ongoing conflicts between the Aplin family and Vietnamese American fishermen. Rudy Aplin recounted to Houston Post reporters that he ran into trouble with a group of Vietnamese American fishermen a month before the murder when he and his wife were running their crab traps in the San Antonio Bay. When the Vietnamese American fishermen attempted to drop their own traps close to his, Aplin said that he “tried to tell the Vietnamese . . . and show them” that there was a “general understanding—you don’t set your traps between someone else’s.” However, the Vietnamese left and later returned with “six boats with men holding knives and machetes” that began to circle Aplin’s vessel, attempting to intimidate him. Aplin immediately called the sheriff and the Coast Guard, who, much to Aplin’s dismay, informed him “there was nothing they could do” about the Vietnamese since there were no formal rules for crabbing relating to traps and there was no proof that the Vietnamese men threated him or his wife. This confirmed Aplin’s suspicions that the state authorities were giving the Vietnamese special treatment and that “we [white fishermen] need at least equal privileges in our country.”23 Later, Chinh claimed that both Billy and Rudy harassed members of the Vietnamese community regularly while both groups were out setting crab traps months before the incident.

A few days after Billy Aplin’s murder, however, Seadrift exploded with violence, igniting a “crab feud” between Vietnamese American and white fishermen. On Saturday, August 4, a Vietnamese home and three Vietnamese boats were burnt and destroyed (the police described the damage as “slight”). Although police investigated the incidents over the weekend, they filed no charges and identified no suspects. For the Vietnamese, this was a travesty and proof that they did not receive special treatment. Tuyen Nguyen, an employee at the Brown and Root crab processing plant in Seadrift, a local leader for the Vietnamese community, and a veteran of the Vietnam War, explained to reporters, “We are very scared. We don’t want to get hurt. Anytime there is a problem, we make a report. I don’t know why police do nothing. We have been waiting and waiting. I don’t know why the government will not help us fight bad people.”24 On Wednesday, August 8, police in Port Lavaca (a small fishing village near Seadrift) responded to an anonymous tip that another attack on the Vietnamese was in the works and discovered explosives in the motel room of three local fishermen, Bommy Vandergriff, Terry Jones, and Lester Sprague. The men were held on a $50,000 bond, but because officials found no dynamite (used in the previous attacks on the Vietnamese Americans), no arrests were made, prompting Nguyen to question why the Vietnamese “have never seen police ignore anybody like this anywhere else.”25 Following up on the violence in Seadrift, Rudy Aplin forewarned that his hometown would “blow up like a powderkeg” unless something was done to rectify the situation.26

But rather than blow up, Seadrift witnessed a mass exodus of Vietnamese Americans. As soon as August 8, five days after Aplin’s murder, only 2 of the initial 100 Vietnamese families remained in Seadrift. Most fled to Houston or Louisiana looking for similar employment, or they moved to other bay and Gulf towns and cities in Texas to continue fishing. The loss of Vietnamese in Seadrift also meant a loss of labor for the packing plants where Vietnamese American fishermen often worked to supplement their income during off-seasons. Leon Ruthenberg, the owner of a crab-packing plant in Seadrift who lived year-round in Baltimore, became “outraged” over the treatment of his Vietnamese employees as well as their sudden departure. Ruthenberg asked the U.S. Civil Rights Commission to intervene and hopefully “stir up some White House concern.”27 Although Ruthenberg was not a civil rights activist by any means, his desire to see his plant reopened prompted a visit from Dallas-based Department of Justice representative Robert Alexander on August 11. Upon arriving, Alexander first noted that the few Vietnamese Americans who remained in Seadrift were “shot through with fear” and angry for how one incident had completely ravaged their new lives in America.28 Clearly, this was a problem that extended beyond employment and closed crab-packing plants; this was, as Ruthenberg correctly identified, a civil rights issue involving a group of immigrants who would rather start over again in a new state than risk the violent atmosphere that had engulfed Seadrift.

All eyes were turned to Alexander; residents hoped he would do something, anything, to end the crabbing feud in Seadrift. While Alexander held no authority to impose any restrictions or measures in Seadrift, he could make recommendations and request assistance from the Department of Justice and other agencies in seeing them through. Rather than approach the conflict as a civil rights issue, Alexander joined other local officials to stress that “communication is the core of the problem” in Seadrift and that if both feuding sides could come together in frequent meetings, the tensions could dissipate and life in Seadrift return to “normal.”29 Former mayor Billy Wilson, a shrimper himself, agreed with Alexander’s assessment and added that “the feud involved nothing more than the local fishing customs” and that misunderstandings or miscommunications had prevented the Vietnamese refugees from adapting to the fishing culture of Seadrift.30 Peter Van Tho, a Vietnamese American representative from the U.S. Catholic Conference who arrived in Seadrift with Alexander, met the Vietnamese American and white fishermen to discuss means of ensuring proper communication between both parties in the future. One solution appealed to both the Vietnamese and others: using local Catholic charities to train and select one native Seadrift resident to serve as a go-between and a Vietnamese priest from another diocese who understood the refugees to “live in the village and arbitrate disputes over fishing rights.”31 The Vietnamese representative would also be expected to teach the Vietnamese the “unwritten rules” of crabbing in Seadrift. These suggested measures unintentionally placed the onus on the Vietnamese American fishermen to learn better communication skills and fishing practices and downplayed the potential racial tensions. However, Alexander and the community hoped that these innovations would “reduce fear” and help the Vietnamese Americans to “gravitate back” to Seadrift because “that’s home for them and everybody wants to come home,” echoing Tuyen Nguyen’s earlier plea for Vietnamese American safety in their new residences.32 Fortunately, news of the attempts to smooth relations between the Vietnamese American and local fishermen reached the families that fled, and by the following week, most of the original refugees were back in Seadrift. The new measures appeared to work. Alexander was happy the Vietnamese Americans returned, Mayor Rayburn Haynie was pleased that his city was moving beyond the negative publicity, the local Vietnamese representatives were relieved that things were safe, and Leon Ruthenberg was thrilled that he was “getting his people back” and reopening the crab-packing plant. By the end of August, the flare-ups between the Vietnamese Americans and the local fishermen died down, and the situation appeared to be “back to normal.”

But the calm waters of the San Antonio Bay and the resumption of crabbing hid the racial and civil rights issues that were left unresolved. Even some of the local fishermen interviewed by the Post at the height of the crabbing feud spoke in hushed voices of what they considered to be the “racial undertones” of the tensions and the persistent resentment of “a few bad apples” among the native fishermen as a result of the Vietnam War.33 For example, Lee Casterline owned Casterline Fish Company (a middleman fish wholesaler) in nearby Fulton, Texas, and he and Lou LeBlanc, a wholesaler in Rockport, Texas, were the only two who would purchase the Vietnamese catches each year when others turned them away. Casterline was merely doing business: The Vietnamese usually had the largest catches and accepted the best prices. Casterline paid little attention as to who his clients were until local fishermen began boycotting his business. Locals were unhappy with Casterline for showing the Vietnamese “special consideration” and providing exclusive discounts. The fear of overfishing extended to the practice of buying and selling catches. Local fishermen argued that the Vietnamese were able to drive down prices for crabs because they unfairly competed with local fishermen and got larger hauls through disrespect for the customs of crabbing. Casterline’s business did not suffer without the white fishermen as customers, and to the dismay of the locals, he continued doing business with the Vietnamese.

Casterline saw this as simply business rather than as a racial matter, but when he went out of his way to help the Vietnamese Americans rebuild their boats to meet regulations, he pushed the locals over the edge. In 1980, Casterline and his father, who co-owned the business, hired Steve Yates, a naval architect based in Victoria, Texas, to draw plans for reducing the cargo capacity of the Vietnamese shrimp and crab boats. Yates modified the boats to meet regulations by installing subdivisions using deep frames below the deck spaces. Casterline also went one step further and allowed the Vietnamese to dock their boats at his warehouse. When asked why he did something that seemed so revolutionary at the time in terms of relations between the Vietnamese Americans and the locals, Casterline shrugged and said, “We just figured the Vietnamese are getting pushed around unnecessarily” and mentioned that his father hated to see racial minorities treated poorly after he had worked on a ranch in Tivoli, Texas, and witnessed African American workers “treated like slaves.”34

When the local community learned of Casterline’s assistance to the Vietnamese, things started to get, in the words of Casterline, “pretty hot.” Locals accused Casterline of helping the Vietnamese violate boating laws and regulations (despite the previous Coast Guard survey assuring that overall the Vietnamese obeyed the laws) and began to have closed-door meetings on the topic. One parishioner in Seadrift warned Father Gregory Dean that he’d “better watch out” because “there’s going to be lead flying very shortly over the Vietnamese, your friends.”35 Casterline, Father Dean, and LeBlanc attempted to reach out to Governor Clements again for assistance in stemming the potential violence, but their efforts were already too late. While few spoke openly of the racial side to the fishing feuds between the Vietnamese and the locals, that was soon to change when the Ku Klux Klan responded to the complaints lodged by the local fishermen against Casterline and LeBlanc. Bullets would indeed fly within a year’s time in the bay region.

Although the Klan was well established in Texas and had attracted members and sympathizers for decades, the organization made its presence known in the shrimping and crabbing feuds in 1980 when members began to leave their “calling cards” at the homes of persons they felt were coddling Vietnamese Americans. Naturally, Casterline was one of the first “traitors” to receive such a greeting from the Klan. Although Casterline never engaged in any direct confrontation with Klan members, one morning he awoke to see a business card taped to his door that read, “You’ve been paid a friendly visit by the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Be careful. Your next visit might not be the same.”36 Others, including LeBlanc and Casterline’s father, began to receive similar thinly veiled threats from the Klan. Another woman who lived in the Galveston Bay area received the same calling card because she allowed a Vietnamese American man to dock his boat on her property for two years. Later, she received three threatening phone calls: one asking if she knew where her children were, the other threatening to burn her boat, and the third stating that she “would die that night.” Although she couldn’t prove that the calls were connected to the Klan, the calling card led her to believe that the organization was behind the threats.37 Soon enough, Vietnamese American women also discovered the Klan’s calling card at their homes while their husbands were away fishing. The women appealed to Casterline for protection, as he had gained a reputation for looking out for the Vietnamese community. Huong Thi Pham viewed Casterline as “like our Dad” who “took care of the Vietnamese” and “protected us during the time the KKK came over to give us a hard time.”38

Klan calling card (undated) from Texas submitted by the VFA as evidence during Vietnamese Fishermen’s Association v. Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Courtesy of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Shortly after the appearance of the calling cards, violence similar to what had happened in Seadrift after the Aplin murder engulfed Rockport and Fulton. Corresponding to the introduction of the Klan calling cards was a series of tire slashings and boat burnings across the area. No suspects were ever identified for these crimes, leaving Vietnamese Americans to wonder once again why the police were not assisting them. However, on February 14, 1981, the Ku Klux Klan held an anti-Vietnamese rally in Santa Fe, Texas (approximately twenty-five miles north of Galveston), and many people in the region connected the Klan to the increasing incidents of arson in the area.

Gene Fisher, a swimming pool installer from Kemah, Texas, contacted Louis Beam, Grand Dragon of the Texas Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, and begged for some sort of intervention in the matter of the Vietnamese in order to raise awareness nationwide of the plight of the American-born shrimpers and crabbers.39 Beam, a Vietnam veteran, native Texan, and longtime member of the Klan, deeply believed in protecting Americans from immigrant invaders through any means necessary, including violence. Beam would go on to an illustrious career in white supremacy and underground militancy, but in the early 1980s in Texas, he devoted himself to training “able-bodied and hardy men” to be part of a militia for “self-defense.” Knowing these credentials, Fisher asked Beam to host a Klan rally in Santa Fe, and Fisher’s friend and sympathizer Joe Collins offered to let the Klan use wide-open acres of his own land for the event. Fisher and Beam distributed thousands of flyers advertising the rally and fish fry and garnered the attention of both local fishermen and reporters from various Houston and area media outlets. Ultimately, 200 participants showed up for the rally (including approximately 50 to 75 reporters), falling well below the expected 1,500.

Although the Klan failed to raise the hoped-for amount of money from rally tickets, they certainly, as Beam explained, “got a million dollars worth of publicity.”40 Beam was naturally the star of the show that day, delivering speeches enflamed with racial and pro-American rhetoric. Validating the fishermen’s claims that the Vietnamese Americans received preferential treatment from the government even though they were not American citizens, Beam proclaimed that the Klan was giving the federal and state officials ninety days to enforce applicable fishing laws or “the Klan and the fishermen will enforce the laws themselves.”41 If there were any doubts among the crowd as to how the enforcement was to be done, Beam quickly cleared up the confusion. The local fishermen were to “prepare to reclaim this country for white people,” and they were “going to have to get it the way the founding fathers got it—blood, blood, blood,” Beam shouted to the small but militant crowd before him. The Klan advertised its “training camps” located throughout the Texas countryside, and Beam explained that he was “more than willing to select some of the more hardy fishermen” to be trained in “self-defense,” making them “ready for the Vietnamese” by the time they were done.42 To make sure that attendees knew who the enemy was and which group of nonwhite people they should be most concerned with, Beam then set fire to a small boat once owned by a Vietnamese American family who had fled the area following violence, and he displayed the Klan’s signature burning cross in “opposition to the Vietnamese fishermen.”43 A month later, on March 15, Beam held another rally where he hung an effigy of a Vietnamese American fishermen from a boat and set it ablaze before the crowd, a blatant message illustrating who the enemies were and what was to be done with them. Following the display, Klan members piled into boats with their rifles to conduct a “parade” through Clearwater Creek (a commercial waterway with businesses and private residents lining both sides) to demonstrate the presence of the Klan and its purpose.

The nature of the Klan rallies created controversy but also unveiled the racial tensions underlying the crabbing and shrimping feuds. The presence of the Klan was not overlooked. As a historically racist organization bent on promoting and protecting white supremacy, the Klan became a fixture of the fishing scene in Texas during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Beam and the fishermen who came out in his support called on the reputation of the Klan in encouraging others to view Vietnamese Americans not only as an economic threat but also as part of a larger “invasion” of immigrants and nonwhites dedicated to taking control of the country. Likewise, a complicit government was to blame for the deterioration of Texas and the nation and the undermining of the white man. The Vietnamese Americans in Texas were a particular conundrum for the white fishermen. Not only were they immigrants (and largely unwanted at that), economic competition, and a racial minority that did not fit neatly into the image of the Asian model minority, but they also reminded whites of the “enemy” from Vietnam. When Gene Fisher explained that “North Vietnamese soldiers are coming into this country. That’s why there were armed men on that boat ride,” he identified all Vietnamese immigrants as the enemy, giving them both a racial and a political identity that encouraged harassment and violence.44 Vietnamese Americans were a new type of “other” in the South following the Vietnam War and prompted a reaction of xenophobia, racism, and working-class disdain for economic competition from minorities who received special privileges from the government. It was a classic outcry from white Americans in the United States during the economic hardships and stagflation of the 1970s under the Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter administrations. The racial tensions between the two parties already existed before the Klan arrived on the scene; however, Beam pulled the tensions to the surface by drawing on an organization with roots deep in the South. His call to reclaim the United States from the Vietnamese and protect it for white people was not so different from the calls of previous Klan members to redeem the South during Reconstruction and into the twentieth century. And as the Klan had done previously, Beam and his supporters would also turn to violence and intimidation to achieve their goals while racializing Vietnamese Americans.

The following month, more violent acts occurred in Seabrook. At 2:30 in the morning on Sunday, March 29, 1981, two boats belonging to Vietnamese American fisherman Phuong Henderson were set ablaze. The boats had been listed on a public auction notice, since many Vietnamese were attempting to flee Seabrook following the Klan demonstration in February. Once again, police investigated the arson but found no suspects in the case, further frustrating the Vietnamese American fishermen who, at this point, were mainly interested in selling their assets, abandoning their investments in shrimping, and moving to Louisiana, where the fishing industry was more diverse and the demand for labor higher. Few of the white fishermen voiced their suspicions of who set fire to Henderson’s boats, but Nam Van “Colonel Nam” Nguyen, a leader of the Vietnamese American community in Seabrook and a former member of the South Vietnamese Army, explained to reporters that the refugees believed the Klan was behind the fires. He pointed to the recent Klan rally and specifically Beam’s inflammatory remarks and “lesson on how to burn a boat” as evidence.45

Remains of a Vietnamese American fisherman’s boat in Seabrook, Texas, 1981. Photo by Mark Toohey/©Houston Chronicle. Used with Permission.

The response to the concerns of the Vietnamese about the growing power of the Klan resulted in attempts to defuse the situation, mainly by encouraging Vietnamese Americans to relocate. Once again, local charities and religious officials offered a solution to the problem that ultimately would reward the aggressive tactics of men like Beam. Earlier in February, following the Klan rally, a representative of Governor Clements traveled to Seabrook to reassure the fishermen that state officials were looking into ways to resolve the growing tensions between the Vietnamese Americans and the locals. After receiving advice from his staff in attendance at the meeting, Clements “pledged to call on voluntary agencies . . . to try to calm hostilities at fishing ports.” Such efforts consisted mainly of “helping Indochinese fishermen to go inland for jobs.”46 Clements’s pledge appeared to be more supportive of the fishermen than the Vietnamese Americans, but in March, Christian leaders from the Houston area responded by holding a conference on Vietnamese refugees. Presbyterian, Catholic, and other Christian denominations united and wrote an official statement on the tensions and violence occurring in Seabrook and other Gulf towns and cities. Richard Sicilano, presbyter of the Houston-based Presbyterian New Covenant and president of the Texas Conference of Churches, lamented that “while we specifically condemn the slurs and violence-inciting activities of the Ku Klux Klan and similar organization, we also know that as Christians and Americans, we should be speaking up for you and other refugees.”47 Sicilano was concerned that conference attendees were focusing too much on conflict avoidance and not enough on actually getting to the root of the problem. But Paul Doyle, the assistant director of the local Catholic Charities group, spoke for the majority of the conference when he explained that relocation “is a poor solution to the problem, but no better one has been suggested. Something’s got to give and the Vietnamese say they’ll give.”48 Many Vietnamese Americans were indeed more than willing to flee Texas to protect their families and their property. Doyle reiterated that the Vietnamese refugees were “welcome in the United States” and that the country was a “nation of immigrants,” but relocation was, “at best . . . a short-term solution to a difficult problem that belongs to all of us.”49 Few of the leaders truly believed that relocation was a good solution, but they argued that getting the Vietnamese Americans out of Texas was the only way to ensure that no more violence would embroil the fishing industry. It was once again a solution that did not address the Klan and the racism and violence that undergirded the current problems.

However, not all Vietnamese Americans in Texas wished to flee, and many opted to fight the Klan through the courts. As tensions mounted in Seabrook and other towns and cities, the Klan announced that another rally and parade would be held at Kemah, Texas, on May 9. Fearing yet another wave of violence after the planned rally, members of the VFA, an organization of Vietnamese American fishermen from around the bay who desired to learn more about the local fishing culture and build better relations with white fishermen, joined forces to seek protection from the Klan. Although the Vietnamese refugees were not American citizens and many were frightened refugees with no other options than to either remain in Texas or flee to Louisiana or another nearby Gulf state, they also knew that the Klan used racially incited violence to intimidate them and keep them out of the waters during the shrimping and crabbing seasons. There were no “official” rules on crabbing and shrimping but, rather, only social customs and norms, meaning that Vietnamese Americans were as entitled to their fishing and property rights as any other American citizen or subject. More importantly, the Vietnamese refugees also knew that their civil and human rights to protection of life and property were violated by the Klan and the unknown individuals who torched their boats and property, and that the police had failed to find suspects and press charges.

On April 16, 1981, the VFA filed a civil rights suit for an injunction against the Ku Klux Klan in the Houston Federal District Court, overseen by African American Judge Gabrielle McDonald. The Vietnamese fishermen, led by Colonel Nam, charged that the Klan, together with the Seabrook-Kemah Fishermen’s Coalition, Gene Fisher, Louis Beam, James Stanfield (Grand Titan of the Texas Klan), and Joseph and David Collins (the two landowners who hosted Klan events, including the previous rally), “violated their rights under several civil rights statutes . . . including the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, and the common law torts of assault, trespass to personal property, the intentional infliction of emotional stress and intentional interference with contractual relations.”50 In order to regain their rights, the Vietnamese requested that the court “restrain the defendant from undertaking activities undertaken with the purpose of interfering with the rights of the plaintiff class, unlawful acts of violence or intimidation . . . , engaging or inciting others to engage in acts of boat burning, armed boat patrols, assault and battery, or threats of such conduct.”51 The VFA also argued that the Klan’s use of paramilitary techniques and Texas land to conduct their training violated Texas law. The VFA was specific in its insistence that Fisher, the Collins brothers, and other fishermen from Seabrook and Kemah “conspired with the Klan . . . to receive training in the use of automatic and semi-automatic weapons, explosives, and other methods that can cause mass destruction and death” at the Klan paramilitary training camps near Santa Fe, Texas.52 The fact that Beam had been arraigned in federal court in Dallas a few weeks prior on a misdemeanor trespassing charge pursuant to the fact that he had conducted a paramilitary training camp on federally owned grasslands appeared to support the Vietnamese claims that violence and militancy were tactics that Beam and the Klan embraced.53

Morris Dees, a civil rights attorney and founder of the SPLC in 1971, agreed to represent the VFA in court free of charge and identified a potentially powerful and revolutionary case in the litany of civil rights battles that typically focused on African Americans. Although some Vietnamese Americans still insisted that they would agree to leave the Galveston Bay area if an opportunity arose, Dees and those Vietnamese Americans who filed the case believed that the Klan’s actions and use of intimidation to protect white business investments should be stopped once and for all. This was a specific instance of Klan violence directed toward the Vietnamese Americans, but a precedent-setting victory against Beam and the others held the potential to redefine civil rights through ending the use of racial intimidation and other de facto forms of discrimination and prejudice nationwide. Earlier in the 1970s, Dees and the SPLC formed a group, Klan Watch (today known as the SPLC’s Intelligence Report, which monitors hate groups), to keep track of Klan activity primarily in the South. Dees was surprised to hear of Klan activity in northern Alabama and other southern states as late as the 1970s and 1980s and wanted to help people who were victims of intimidation and violence from the group. Dees began building a reputation for taking on the Klan directly throughout the South when, in 1981, a Vietnamese American fisherman reached out to him to let him know about Klan activity in the Galveston Bay area. The SPLC and VFA fight against the Klan proved that although many considered the organization as a fringe group after the 1970s, the Klan was still real and terrifying. For Dees, this was another example of the Klan clinging to age-old ideas of white supremacy, regardless of the target.54

The legal strategies that Dees and the VFA pursued in Vietnamese Fishermen’s Association v. The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan revealed the changing nature of civil rights battles in the 1970s and beyond. Their claims of Fourteenth Amendment rights violations were more traditional: They argued that the Klan denied them equal protection through intimidation and threats. Dees also used civil rights statutes that Congress passed following the Civil War, and although they were initially meant to protect the rights of African Americans, they were expanded thereafter to include what Dees described as “class-based animosity,” rather than just one specific racial group.55 However, the VFA suit for an injunction rested more on tort law and the Sherman Anti-Trust Act than on constitutional protections. Dees and the VFA included a smattering of Texas civil rights codes in their suit, but it was the argument that the Klan denied the Vietnamese refugees their rights to their livelihood and, as such, their safety and peace of mind by violating business practices that would make the case a unique addition to civil rights battles in southern courts. Previous Asian immigrants (including Lum Jung Luke from Arkansas, discussed in Chapter 1) living on the West Coast also used the courts to fight for property rights with post-Civil War civil rights legislation and the Fourteenth Amendment during the late nineteenth century, and the Vietnamese refugees continued this legacy in the South.56

The Klan’s alleged use of intimidation and threats to drive the Vietnamese Americans from Texas and the fishing industries became the focus of the case as well as the basis for the argument that the Vietnamese Americans suffered from various tortious interferences. One of the most problematic aspects of the case for the plaintiffs was that there was no hard evidence that Beam, other members of the Klan, or any other white fishermen had directly inflicted violence on the Vietnamese Americans. When Beam provided a deposition to the court before the trial, he was careful to stress that he was not opposed to the Vietnamese people but, rather, that he “stands for white people . . . [who] have certain rights.”57 He also clarified that he was against the Vietcong, not the Vietnamese, and often ate dinner with Vietnamese families around Galveston Bay and wished to help them “get their country back” from the Communists.58 He was adamant that he was a law-abiding citizen (in reality, he had been previously arrested on several accounts for harassing socialist protesters earlier in Houston and threatening Chinese president Deng Xiaoping when he visited Texas) and would never incite violence between the Vietnamese American and the white fishermen. At the previous rallies, Beam did not rail against the Vietnamese but, rather, “the federal government and the state government, who [have] turned their backs on the citizens of this country in favor of non-citizens.”59 It wasn’t Beam or the Klan or the white fishermen who were creating tensions but, rather, “out-of-state agitators, anti-Christ Jew persons” like “Demon Dees” (a nickname Beam thought up for Dees in the courtroom—Dees was actually a Baptist) who tried to “stir up foment and discord between them people.”60 Likewise, Gene Fisher, a convicted felon and leader of the American Fishermen’s Association (AFA) who initially reached out to Beam for assistance in dealing with the Vietnamese Americans, swore in his own testimony before the court that the goal of the AFA was merely to limit the number of fishermen on the bay, not to single out the Vietnamese Americans. Fisher only contacted Beam to raise media attention to the plight of the fishermen and to discuss “different forms of protest, different forms of legal protest within the framework of the Constitution of the United States.”61 True, Fisher stated clearly his belief that Vietnamese American fishermen did not have the same rights to livelihood as white fishermen, and he did not deny that he said at the Klan rally that he would make trouble for those who did business with the Vietnamese Americans. He did not deny that he explained that “unless the large influx of Indo-Chinese refugees was halted, there would be continued boat burnings. . . . There would be continued loss of life, loss of property,” or that he “was going to keep fishing if he had to run over every gook on the Bay.”62 But personally, he didn’t hate Vietnamese refugees. He was just an average American who grew tired of watching his rights violated by immigrants while a weak government indifferently looked on. In fact, as Fisher claimed, it was the Vietnamese Americans who had killed Billy Aplin and who should be under suspicion, not the Klan or any of the white fishermen.

Other members of the AFA who appeared on the stand confirmed that the Klan was never enlisted to help with terrorizing Vietnamese Americans and that they and the Klan were falsely accused of harassment. The rallies and boat parades were merely media spectacles to get the government involved (Fisher explained that the effigy was of an “Indian,” not a Vietnamese refugee, to protest the government’s treatment of the white fishermen as they had treated the Native Americans) and limit the number of refugees coming into America. There were no direct threats made to the Vietnamese and no way to connect the boat burnings to the Klan or the white fishermen. According to all of the defendants, the Vietnamese and white fishermen could work together peacefully without “race-baiters” like Dees and the SPLC intervening.

Members of the Vietnamese American community who provided depositions and testimony before the court failed to deliver any proof that they experienced violence from the Klan or the AFA. Samuel Adamo, attorney for Beam, pressed the Vietnamese Americans who took the stand to think carefully about what they considered to be acts of violence. Many of the Vietnamese Americans who testified described instances of intimidation, but not necessarily of direct violence. Tran Van Phu, vice president of the VFA, explained that following the Klan parade at Clearwater Creek, many whites refused to let Vietnamese fishermen dock their boats and brandished guns in order to emphasize their point.63 Tran also offered that a house on Road Number 6 near Seadrift flew a KKK flag and displayed a coffin with the Vietnamese flag draped over it that served to intimidate the other Vietnamese in the area and to drive them out.64 These incidents, combined with the arson demonstration at the Klan rally and Beam’s cries to force the Vietnamese Americans from the bay, frightened Tran “because the act of burning the small boat . . . could affect the big boats” and lead to more arson.65 But when Adamo asked if any of these incidents had been violent enough to keep him from fishing, Tran replied no because he had too many debts to pay.66 For Beam and Adamo, this was a victory: The Klan’s statements may have frightened Tran but not to the extent of actually driving him from the bay.

Colonel Nam’s testimony brought into the courts the question of whether or not the actions of Beam and others could be considered “violent.” At one point during his examination, Nam told Adamo that the Vietnamese did in fact suffer from violence when a group of white fishermen threw rocks at a Vietnamese boat during the Clearwater Creek parade. However, when Adamo pushed him to more clearly define what he believed to be acts of violence, Nam’s certainty dissipated. “Violence, according to me,” Nam explained, “I know that men kill people with the gun and with the physical action by weapon. I think that’s violent.”67 Adamo picked up on this and provided Nam with different examples of violence, one being the throwing of rocks and the other being “beating someone to a bloody pulp.”68 These were opposite ends of a spectrum of violence, but Nam ultimately agreed with Adamo that throwing rocks was minor when compared with being beaten to a pulp. Because Beam, the Klan, or any of the other defendants had not directly assaulted Vietnamese Americans, there were no acts of violence. If there were no acts of violence and many Vietnamese Americans continued to go about their business as they would have whether or not the Klan parade had occurred, then it was Beam’s and the defendants’ rights to free speech and assembly that were violated. Intimidation was not the same as violence, but it was difficult for Vietnamese Americans to prove that they were in fact intimidated by white fishermen when they continued with their daily activities. Nam quickly recanted, though, and further explained that intimidation could be violent when considering its potential results. Nam explained that although no Klan member or white fisherman had directly attacked a Vietnamese fisherman that he was aware of, there were still acts of “lawful violence,” meetings where the Klan gathered, the parades, the rallies, and other acts that had the intention of inducing fear and provoking later violent actions. “I think act of violence is the KKK,” Nam argued, “after the boat ride, we scared, we think that is unfair.”69 He also explained that the boat burnings were not just intimidation, but acts of violence. “The boat burning, this means the damage to the property of the Vietnamese fishermen. I think it’s severe because they burn boat today, but more then more, over and over again like this.”70 There would be no end in sight, and the violence could escalate unless the Klan and its supporters were barred from intimidating the Vietnamese Americans at the start of the fishing season. But as Nam and the other Vietnamese Americans discovered, fighting for the right to safety and peace of mind from Klan violence was a long and difficult battle.

Proving that the Klan “intentionally inflicted emotional distress” on the Vietnamese Americans between 1979 and the spring of 1981 was challenging considering the testimony given. However, there was little doubt for the Vietnamese Americans that the actions of Beam and other members and supporters of the Klan created an atmosphere of fear and trepidation around the Galveston Bay area. As Judge McDonald discovered, in some cases, members of the Vietnamese American community were so frightened that they fled their homes. Many witnesses, including Phuong Pham (Colonel Nam’s niece), pointed to the March 15 “boat parade” as evidence of Klan intimidation. The parade passed by Colonel Nam’s house (where Pham was living), and Pham recalled being shaken when one of the boats slowed down and a Klan member paused to point directly at her home. Pham interpreted this as a silent threat or at least a form of intimidation. Pham explained that “she was so frightened by the sight of armed and robed Ku Klux Klan members . . . that she ran from Colonel Nam’s home and [was] . . . afraid to spend the night there.”71 Adamo questioned Pham on whether she was more frightened of the man who happened to be in a Klan outfit who had pointed at her house or of the Klan’s reputation, to which Pham replied that she had learned all about the history of the Klan in America and she knew that “they against black, you know,” and hated minorities.72 Pham and others were well aware of the Klan’s legacy of violence and knew to be worried when the organization set its sights on the Vietnamese Americans. Fisherman Nguyen Luu echoed Pham’s concerns following the boat parade, stating, “Out of fear, to this date, I have not bought a license, a permit to go fishing yet.”73 When the defense pushed Luu to explain what he wanted the state of Texas or the federal government to do about the Klan when none of its members had directly attacked or intimidated him personally, Luu stated, “I cannot state what kind of protection I want, because I don’t know, but it’s the domain of the government to give protection to me to operate the business I’m in.”74

Luu’s testimony brought the deeper issues of not only the rights of the Vietnamese refugees but the rights of anyone residing in the United States to protection from intimidation in their business affairs, and the question of the government’s role in providing this protection, to the surface. Beam and his defense insisted that because the Klan had not been in direct contact with any of the plaintiffs or witnesses and had not directly attacked or intimidated any Vietnamese Americans, then there was no lawful proof of intimidation. Regardless of the intent of the boat parade, connecting the Klan to any of the previous attacks on boats and property or any plan to forcibly drive the Vietnamese Americans from Texas was difficult, and any attempt to do so would violate, Beam argued, the basic civil liberties of American citizens. However, the Vietnamese fishermen were frightened enough that many did not engage in their jobs, or they were unsure of how long they would be able to do so now that the Klan was assisting the white fishermen. Pham was not wrong in connecting the nasty history of the Klan to her current situation; it was a white supremacist organization (as Beam and others made clear) founded to protect white Americans. Colonel Nam summed up these points at one point in his testimony, explaining, “I think the Klan people who took to burning a boat [had] an effect to our psychology. We think the Klan know how to burn boat so that we feel intimidated to our person and our people, but I don’t know if this [Klan intimidation] is in United States lawful or not.”75 The Vietnamese Americans were intimidated and claimed emotional distress, but Colonel Nam and those he represented were unsure if the behavior of the Klan was legal. Nam knew that the Vietnamese Americans were entitled to basic protections of safety, but speaking in a court of law, he was unsure if the Klan had intentionally inflicted emotional distress on the Vietnamese Americans.

Texas law, however, was more precise on the matter. According to the state, “damages for mental anguish and fright are not recoverable unless they result from or are accompanied by physical injury.”76 Although some Vietnamese Americans had testified to the Klan throwing objects, there was no proof that any of the plaintiffs in the case were physically injured. In Texas, unless there was specific evidence that the acts of an individual inflicted emotional distress or mental anguish, then there was no ground for suit.

The VFA’s attempt to charge the Klan with intentional emotional distress represented an attempt to fight for human in addition to civil rights. When Vietnamese refugees came to the United States, they brought with them the trauma of the war. Those who came later escaped the political turmoil and violence that accompanied the fall of Saigon and were often mentally as well as physical and spiritually scarred. A burgeoning Asian American activist movement identified a need for mental health facilities and care to help the new refugees cope with post-traumatic stress disorder as well as the challenging process of adjusting to life in the United States with limited means. Free mental health clinics designed to simultaneously analyze and assist the Vietnamese refugees in Los Angeles, Sacramento, and other areas in California faced often insurmountable financial odds and shortfalls, but they provided the most basic services to the mentally anguished and also established training programs for social workers. Such opportunities and facilities did not exist for refugees who came to the Gulf South. Clinics and mental health care professionals were more available for the refugees who settled in or eventually fled the Gulf for cities like Houston or Austin, but refugees in Port Lavaca, Seadrift, Kemah, Seabrook, or Fulton were left to their own devices, relying on their small communities to help them adapt to their new lives. Local charities and Catholic churches assisted Vietnamese refugees with financial matters and provided social opportunities, but they advised relocating as a coping mechanism for the Klan’s intimidation. Many of the Vietnamese were successful in fishing, allowing them a certain level of security, but the actions of the Klan further exacerbated existing stress and trauma from the war and the act of relocating. In the face of intimidation and violence, the only sanctuary for many Vietnamese was to flee to other cities in the Gulf and seek other forms of employment. In the case of the Gulf Coast Vietnamese refugees, fleeing the area in the face of threats was a response to a lack of services as much as it was a response to the Klan.77

When read in the context of human rights law, the fight response of the Vietnamese Americans who went to court was a cry for the human right to security and safety for refugees. President Carter argued as part of his Cold War policy that the United States had a responsibility to assist those (like the Vietnamese refugees) who suffered as a result of earlier American actions and a duty to protect and promote basic human rights. This plan brought the Vietnamese refugees to America and led them to believe that their human right to migration, to escape physical and/or mental torture in search of safety, would be protected. As they explained to reporters when the crabbing feuds first broke out in Texas and as they further explained in court, the Vietnamese refugees believed that America was a chance to start fresh, not another place to experience violence and intimidation. Although the VFA used torts and the language of civil rights violations in its suit, when placed within the context of the post-Vietnam War era and the other experiences of Vietnamese across the country, the push for an injunction against the Klan on the grounds of intentional emotional distress was a plea for human rights. The South’s history of violating civil rights was well documented, however, and the VFA in this instance pushed this idea further in its claims. The Klan’s power over minorities was evident in the case, as was its intent to deprive the Vietnamese Americans of their human rights and refugee status by destroying their economic safety net as well as their mental state. Previous Supreme Court cases as well as local cases throughout the South argued for civil rights and pointed to violations of the Fourteenth Amendment to equal protection against psychologically damaging racial practices, and in this sense, the VFA’s fight was similar.

However, by explicitly referencing mental anguish and intentional emotional distress, this language tied the legacy of racial discrimination to a larger realm of migrant rights, refugee rights, and more importantly, human rights. Technically, the Texas Klan used intimidation to violate Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Right to Asylum in Other Countries from Persecution. When this reading is placed alongside the intimidation that the Vietnamese Americans faced, we see that the Klan then prevented many Vietnamese Americans from enjoying the fruits of their labor and essentially caused a high level of emotional distress and mental anguish that forced them to flee. The VFA members argued in court that they did not feel safe in Texas so long as the Klan continued its systematic use of intimidation and violence, echoing the earlier calls of African Americans who lived under the terror of the Klan during Reconstruction and the civil rights movement. However, the VFA members’ fight for their basic rights as noncitizens was a new move in the “post-civil rights era” and married the civil rights battles of the past to the social, political, and migrant issues of the time. Their fight for an injunction against the Klan was an age-old fight that became larger and more global at this time and brought the southern battle for civil rights onto the stage of twentieth-century human and immigrant rights.

Unfortunately for the VFA, Judge McDonald rejected the claim of emotional distress. Although the VFA “produced sufficient evidence to establish a substantial likelihood that the defendants intended or at least could have reasonably anticipated that the boat ride would cause . . . severe emotional/mental distress,” under Texas law, physical damage must accompany mental or emotional trauma.78 The same need for physical proof of mental anguish applied to the VFA’s claim that the Klan was guilty of assault. Klan members may have brandished weapons on the boat parade; but no one was physically harmed, and the Klan was not close enough to the Vietnamese Americans that day to inflict physical harm. Judge McDonald conceded that “the actions of the defendants created an atmosphere conducive to the commission of violence and that such violent acts were the foreseeable natural cause of the call for violence,” but there were no concrete connections between the actions of the Klan members and the boat and home burnings that occurred before and after the rallies and parade.79 Emotional distress and mental anguish were at the heart of the VFA’s pursuit of an injunction against the Klan, and yet there was little members could do to ensure their mental well-being at the time. While the VFA argued that safety and security from threats and intentional emotional distress were basic rights, the court essentially ruled that protection from physical assault and distress were the only rights that were protected under Texas and, in some cases, federal law. The fact that the Klan did clearly create an “atmosphere” of fear for the Vietnamese Americans as they had done for decades meant little when it came to mental trauma.