Chapter 4

TWO PEOPLES SHARE A HOME

THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY IN THE VALLEY

▲ ▲ ▲

The Boundary Tree Monument is a rather forlorn place this windy November afternoon. No one else stops at the pull-off. In fact, it’s easy to miss the monument entirely, on a quiet stretch of Tsali Boulevard in Cherokee, North Carolina, just across from the Cherokee language immersion school, the New Kituwah Academy. Overwhelmed by a picnic pavilion, the stone monument can be mistaken for something functional because it is downstream of the Cherokee water intake facility. But steps from the road, the marker stands about six feet high. It doesn’t offer much excitement. I guess that’s right, but once this was a place that made a difference to many.

I read the weathered but warm-toned brown brass plaque. In formal phrases, it announces that this is the spot where a large poplar, likely a tulip tree, stood for hundreds of years and marked the division between white and Cherokee land. The divide remained under various authorities, including Great Britain, North Carolina, and the National Park Service.

Of course, the tree is long gone. An article by John Parris of the Asheville Citizen-Times states that the tree was cut down in 1959 because it was a hazard.1 I imagine it as a towering 300-year-old tulip tree, one that could be readily noticed, one that a traveler marked in approach and crossing. Now, even the boundary has moved. In the 1940s, the Eastern Band purchased the 884-acre Boundary Tree tract, which included this area, from the federal government, and used the land to develop a successful Cherokee-owned hotel and diner. The school replaced these in 2009. I like to think some serendipity comes into play with this turn of events. As a result of the sale, the park boundary moved north some, which is indeed marked with a sign that folks regularly use for a photo op. In the 1970s a man living in Macon County claimed to have a coffee table top made from a horizontal slice of the actual tree. But it later burned in a house fire. Look for a photo in Foxfire 4.2 The table, about a yard in diameter, sure looks small to me to have come from an age-old tree. Who can say? Everything changes. I enjoy this quiet place even if its purpose and most of its glory has passed. Here was the line.

▲ ▲ ▲

AFTER THE TREATY OF HOLSTON was signed in 1791, an era of boundary-line expeditions in Tennessee, North Carolina, and South Carolina began, effectively taking former Cherokee hunting grounds and opening them to white settlement. Federal and state agents and Cherokee chiefs worked to survey ceded land and draw clear boundaries between state land and the remnants of the Cherokee Nation. In the years between 1791 and 1802, four boundary lines were drawn that affected the residents in western North Carolina; each of these was disputed and each displaced both white mountain families and Cherokees, infuriating both groups. Also at this time, land in the Oconaluftee Valley began to be granted to homesteaders and land speculators. A process for granting land in North Carolina had existed since colonial days. Eligible citizens or Revolutionary War veterans could go to a county’s land office and register an entry for vacant land. Next, the court would order the land to be surveyed via a land warrant. Once the survey was completed and the surveyor’s plat of the land was approved, a patent was issued by the state, which granted the individual or family the land. As you can imagine, the process could take years, and mistakes could and did occur.3

Even before boundary issues were resolved, in 1796, large tracts along the Oconaluftee and Tuckasegee Rivers were granted to William Cathcart, a prominent North Carolinian. But his title to this land was subsequently disallowed in the outcome of a lawsuit, although he did successfully speculate in land elsewhere in North Carolina.4 Another grant of this period survived similar disputes over boundaries and titles; it was to Felix Walker, a Revolutionary War veteran, North Carolina state politician, and later U.S. congressman. On February 2, 1798, Walker obtained grant #501, an area of 2,560 acres, from North Carolina. This tract began at the Boundary Tree and included the fertile bottomlands of the Oconaluftee up to Smokemont as well as up Raven Fork to the foot of Stoney Mountain. The Boundary Tree was a tree used as a boundary by the British earl of Granville as early as 1743 and again as the dividing line between Burke and Rutherford Counties in 1792. After 1840, the tree marked the line between white mountain families and the Cherokees. This location is now about a mile outside the national park in Cherokee, North Carolina. Walker had no intention of homesteading in the region himself; he was interested in selling the land at a profit to others. Very soon families of German and Scots Irish heritage began buying land from Walker and moving into the area. It is important to note that the best land was affordable only to land speculators and to well-off families; most white settlers could afford only inferior land—that is, land that was not cleared, on a steep slope, rocky, or all three.5 Other families pursued state land grants independently.

Boundary Tree and monument (in foreground on right) marking line between Cherokee, N.C., and Great Smoky Mountains National Park, 1935.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

THE MEIGS-FREEMAN LINE

One of the most telling stories of the drawing of boundaries comes from a fragment of a journal by surveyor Thomas Freeman as he joined an expedition led by Col. Return Jonathan Meigs. This 1802 expedition drew a line from the crest of the Smokies through Oconaluftee Valley and beyond to the confluence of the Little River and the French Broad in South Carolina. Meigs had become the federal agent to the Cherokees the year before at age sixty-three, and he served in that position until his death in 1823. The boundary that became known as the Meigs-Freeman line was initiated to settle disputes that had arisen from previous boundaries to the north and south of the new line. The Meigs-Freeman line was drawn between earlier boundary lines, the northern Hawkins line of 1797 and the southern Butler line of 1799. The new line was intended to limit disruption of both white and Cherokee settlements, placing the Cherokee Nation to the south and west of the line and the United States to the north and east.6 More specifically, Meigs’s purpose was to ensure that the headwaters of the French Broad fell within North Carolina so that white mountain families’ farms in this area were protected from future dispute.7

Meigs set out from his office at South West Point (Kingston, Tennessee) in July with Freeman and a company of sixty white and twenty Cherokee men to carry provisions, measuring chains, and other instruments to mark blazes along the new line and, in the case of the Cherokees, to serve as guides and interpreters.8 All were paid for their labor; when the route became too steep for pack horses, the rate per person was set at one dollar a day.9 The expedition began in earnest in late July when the company departed from the base of what is now known as Meigs Mountain to ascend the crest of the Smokies. They proceeded slowly, blazing trees with gashes that would remain as scars and marking the line as best as possible in the rough terrain and despite views limited by clouds, mist, and rain. The western end of the new line was placed at the top of Mount Collins and was marked by a post, called Meigs Post, which has served as a key geographical point since it was established, designating the Tennessee–North Carolina boundary as well as boundaries for many later land sales and forest plots by lumber companies. Meigs Post was a key marker when these lumber companies sold their land to Tennessee and North Carolina in the twentieth century to establish the national park.

Freeman’s journal records August 17, 1802, as the day the survey party reached and marked Meigs Post:

Thermometer 51°. Ordered the Pack horses to meet us on the line in the Indian Country by going up the waters of the French Broad. Supposed to require about eight days. A Spring at our Camp being very cold was found by the Thermometer to sink the Spirit to 48°.

We marched 3 miles to a position on the G. Mountain, Erected a post of Spruce pine 15 inches in diameter, Six feet high, pointed at top, drawing a line from top to bottom to designate our course & marked on the north side U.S. 1802. R. J. Meigs AWD. T. Freeman, USA. & on the south side C.N. U. and E., Cherokee Chiefs. Erected a mound of Stones around the post of about 2 Tons of Stone, wh. with difficulty we collected having no Tools for digging. From this monument we commenced our line between the Cherokee and North Carolina and descended the mountain 45 chains and Encamped on its Side, Laurel being very thick.10

On the south side of the post, the initials C.N. indicate “Cherokee Nation” followed by the initials of two chiefs. Possibly these men were Unaketa or Unalouskee (Junaluska, perhaps, whose first name was Gul’kalaski) and Elijah Ryan, who was mentioned in related documents.11

Over the next three days, the party marked the line down through Deep Creek, over Thomas Ridge, and arrived in Oconaluftee Valley on August 20: “Sunrise Thermometer 65° Our provisions being nearly out Sent our Interpreter & two Indians to the Bears Town to purchase provisions delivering him Ten dollars & 10 cents. continued our Survey on a ridge & on Over a turn of it descending the side a steep declivity over a stream of 50 links wide ascending & descending a high mountain to a fine stream of water & encamped on the West side of it. Killing two rattle snakes on the route wh[ich] makes 5 killed since commencing the Survey.”12 The stream that measured fifty links wide (about thirty-three feet) was probably the Oconaluftee, and the “fine stream” may have been Soco Creek.13 This day would have led the party close by the Boundary Tree.

From Soco Creek, the company proceeded to John’s Town and to Bear’s Town (both now near Sylva, North Carolina). The Bear of Bear’s Town was Chief Big Bear, or Yona Equah.14 Whether or not Yona Equah was related to the later Chief Yonaguska, Drowning Bear, is unclear. Yonaguska emerged to become one of the pivotal leaders of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Nation in his efforts to preserve the homeland of the Lufty Indians (as Cherokees who resisted removal were called) by successfully resisting the inducements and coercions of the United States for Indian removal to Arkansas and Oklahoma.15 Nonetheless, the last three surviving entries of Freeman’s journal suggest that Yona Equah was himself sharply focused on maintaining Cherokee lands in North Carolina:

23rd Thermometer 64° Sunrise Continued the line to Johns Town where five Chiefs & a number of Indians were assembled who seem much concerned at the running of the line. Having requested the Big Bear the principal chief to go with us on the survey expressed much unwillingness to attend: but will give an answer tomorrow morning. The Indians discovered a friendly disposition bringing us provisions & fruits—more than we could take with us.

24th Thermometer sunrise 68°. Met the Bear and 4 other Chiefs to renew the conversation respecting the line wh they were apprehensive would leave their Settlements on the Carolina Side. they used every argument & [behest] for us to use our discretion; & run so as to leave them on the Cherokee side. They were told [by Meigs] that it was not in our power, and that we were ordered to run the line from one given point to another given point; on our holding to this, the Big Bear refused to attend on the running of the line as he was requested to do. We told him that/ in the/if event of their houses being left out we [would] make a representation of their situation to the Executive [the secretary of war] and did not doubt their case would be favorably attended by the Government.

25th a Council of Chiefs met in the morning & agreed to send forward two of their men Lusena as Chief—the Big Bear having gone off in disgust.16

The remainder of the journal was lost or damaged beyond use; the surviving fragment was salvaged from the White House fire during the War of 1812. Unfortunately, no daily account of the expedition’s conclusion is available. Nonetheless, we know from Meigs’s own reports to the secretary of war that his line displaced five Cherokee families but no white mountain families. Also, the reports demonstrate that he did live up to his promise to intercede for the Cherokees:

In running the line between the two points directed in our Instructions, not a single Settlement of the White People is cut off or intersected, not coming nearer than one & a half miles of any of their plantations.—On the other hand there is but five Indian Families left on the Carolina side of the line.—In justice to them & on their earnest solicitation, I promised to state their circumstances to the government as those Indians behaved very well but seemed much affected at the Idea of being obliged to leave their little cabins & a few acres of cleared land—I found by inquiry that they were on the land long before the treaty of 1798.17

Though Meigs did right by the Cherokees in this first letter, the discussion of the same situation in a letter he sent two days later, also addressed to the secretary, suggests that the Cherokees had to relocate anyway but received additional compensation, perhaps in land: “They [the Cherokees] received an addition to their amnesty in consideration of that relinquishment—in this respect the precedent they plead does not apply—they have nothing to give—There are but five Indian families cut off by the line—I took account of their number, their Cabbins, Stock, cleared land, &c.”18 Meigs had integrity and kept his word, but he was the federal agent, and in this instance and many later ones his decisions show that even though he was sincerely sympathetic to the needs and circumstances of Cherokee families, he was always loyal to the United States and its interests. A subsequent description of the entire area by Meigs attests to his grasp of the desirability of the land to white farmers and lumbermen:

That part of the Cherokee Country on the South Side of Tennessee River except the mountainous trail, mentioned lying below the North Carolina line which was run by Mr. Freeman in 1802 is a very desirable & valuable Country, including the Highlands on both sides of the River—The Soil and seasons seem peculiarly calculated for raising Cotton & Corn & wheat has come by well in the few Instances when it has been tried—and immense numbers of Cattle may be raised with only the expense of salt being given them—large numbers raised even without the expense of that article—Mr. [name illegible], last year had five hundred head, he told me that he gave them nothing but Fatt at proper seasons.

I have omitted mentioning the kinds of Timber on the different portions of The Country On the great Iron or Smoaky mountains & in other high mountains that is, particularly on the Western & Northern sides a great deal of the Spruce pine, which gives them a cold & dreary appearance—On the smaller mountains & hills & on the level grounds, are all the different kinds of Oak, Hickory, Poplar, Pine, Sasafras, Dogwood & frequently all these are mixed on the same tract—and the common pine is not here, as at the Northward, an indication of poor land—On the Border of the River, there is Elm, Buckeye, Poplar, Cottontree, Persimmon & Cucumbertree, Sugar beech—.19

Given this description of fertile farmland and valuable forests, it is no surprise that Felix Walker’s land in Oconaluftee Valley was soon sold to a number of settler families. On farms from Walker’s large grant in what was then Buncombe County, the families of Jacob Mingus and Rafe Hughes first settled in the Raven Fork area, known today as Ravensford (though this name was not used until the twentieth century). Abraham Enloe also bought Walker land in Ravensford very early in the nineteenth century and established a home near the current ranger station and visitor center.20 Other early families included those of Robert Collins, Isaac Bradley, and John C. Beck, soon to be followed by the Conners, Floyds, and Sherrills, among others.21 The names of these families now dot the map of the park, so dominant were they in the valley’s nineteenth-century history.

Though not always a dependable way of locating a family’s homestead, geographical names often indicate nearby homesites. The Mingus family established its mill on Mingus Creek on the west side of Highway 441. Just across Newfound Gap Road and the river lies the bottomland where they farmed and built a home around 1810. East of this original homesite, on the east side of Raven Fork, Mingo Falls suggests the approximate location of Ephraim and Sophia Mingus’s farm in Big Cove. Samuel Sherrill’s family is memorialized by Sherrill Cove, also on the south side of Raven Fork, which is now close to the park boundary and to the Blue Ridge Parkway. Rafe Hughes and his family established a farm at the fork of Raven Fork and Tight Run, now along the road entering Big Cove and at the base of the long ridge that carries this family name.22 Further upstream but below Smokemont, Becks Creek indicates where the Becks settled. Above Smokemont, Bradley Fork, a major tributary of the Oconaluftee, locates the Bradleys’ farm. Moving up the valley, the mouth of Collins Creek marks the location of the Collins family home, later bought by a branch of the Conner family.

Because the white community was small, families intermarried and property shifted from one to another. For example, the Mingus farm became known in 1870s as the Floyd Place because Sarah Angeline Mingus, the daughter of Polly Enloe and Dr. John Mingus, married Rufus G. Floyd. Their son John Leonidas Floyd, a great-grandson of Jacob and Sarah Mingus on his mother’s side, inherited the farm after Dr. John’s death. In addition, the Enloe farm was bought by the Floyd family in the first decade of the twentieth century, after the death of Wesley Enloe, who had lived there all his life and nearly all of the nineteenth century. Many of the homesites in the park changed family ownership through marriage and inheritance of the original handful of families.

At this time, the Cherokees lived in small towns and individual homesteads south of the Meigs-Freeman line, which means that they were mostly squeezed out of the park area, as well as out of Big Cove. They occupied sites within the Oconaluftee Valley around the current cities of Cherokee and Ela, North Carolina. In 1808 Meigs commissioned a census of the North Carolina Cherokees from George Barber Davis, who reported that in comparison to the more white-assimilated Cherokees in Georgia, those in North Carolina “are at least twenty years behind the lower town Indians.” This assessment meant that they were more traditional in their religious beliefs and less interested in Christianity, that fewer spoke or read English, and that their subsistence lifestyle was less influenced by metal tools and colonial production processes. Farms in North Carolina were smaller than those in Georgia, and only a tiny fraction of North Carolina Cherokees owned slaves to help with farmwork. Of the 583 Black slaves in the Cherokee Nation at this time, only 5 were in North Carolina. Despite being the home of about a third of the entire Cherokee population, with 3,648 individuals, those in North Carolina owned only forty plows out of 567, 270 spinning wheels out of 1,572, and 70 looms of a total of 429.23 In part, the reason for these impoverished circumstances was that the North Carolina Cherokees did not benefit as much as the Georgia Cherokees from federal “aid” because they were distant from the center of the Cherokee government located in the Lower Towns and, later, at the capital city of New Echota in Georgia. This is where Meigs doled out tools and other goods as part of the United States annuity to the Cherokees for land cessions. But it is also the case that the North Carolina Cherokees were generally more resistant to the federal policy goal of civilizing the Cherokees to live and believe as whites and to eventually assimilate into white society.

At this point, the North Carolina Cherokees were finding their separate answers to the pressures of white society. According to legend, in 1811, they resisted the persuasion of Shawnee chief Tecumseh when he spoke at Soco Creek in an effort to raise a pan-Indian confederation against the United States. Although younger men were tempted to join Tecumseh, Gul’kalaski, a chief who later distinguished himself as an ally of the United States at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814, counseled friendship with whites.24

“PILGRIMS OF DESTINY”

By most accounts Jacob and Sarah Mingus were the first white settlers along the Oconaluftee. They farmed much of the bottomland of Oconaluftee River and Raven Fork in the nineteenth century. They had four children and became pillars of the community. The family’s prominence was marked by its support for an early church and school. Both Jacob and his second son, Jacob Jr., served in the infantry during the War of 1812, enlisting as privates. Much later, in 1879, Sarah received a land warrant for her husband’s service; similarly, in 1850 Jacob Jr. received 160 acres for his.

During these early years of settlement, the families focused on building cabins for shelter and clearing land for their farms. Detailed records of these first homes do not survive, but they likely would have been relatively simple log cabins with few windows, overhanging roofs for porches, stone chimneys, and loft sleeping chambers. As the families and their fortunes grew, the homes expanded as well, with additional rooms, floors, and outbuildings. The earliest farms were situated on fertile bottomland that the Cherokees had previously cultivated, but as farmers increased their acreage devoted to crops and pastures, they would have needed to take down massive trees by axe. The stumps would have been hauled out by an ox team or burned. Trees that were too large to fell were girdled by cutting a deep ring all around the trunk, which cut off the flow of sap and nutrients to the tree and, eventually, killed it in place. Later, once the tree was dead and dry, it could more readily be split and brought down and its lumber used for myriad purposes.25 These families had to be self-reliant and inventive to manage and do the hard labor that was required. They learned, for example, to use sleds made of sourwood tree trunks for hauling because they were easy to make and forgiving on rough mountain trails.26 Sleds made from a fork in a tree were called “lizzards” and could be cut and rigged in a brief time. Similarly, because rope was in short supply, hickory bark peeled from trees served in its stead and could be used to lash items to sleds or for assorted other purposes such as weaving a chair seat.27

The paramount legend of the early years of Oconaluftee Valley belongs to the Enloe family, headed by Abraham and Sarah. In the early 1800s, the well-to-do Enloe family moved from South Carolina to a farm in Rutherford County, North Carolina, then to one along Soco Creek, and ultimately to the 250 acres in the fertile bottomlands of Oconaluftee now occupied by the national park visitor center and Mountain Farm Museum. Already prosperous, Abraham owned and traded slaves and served as justice of the peace. He was known as a successful farmer as well as a good hunter with devoted dogs. Reportedly, he owned the only wagon in the early Oconaluftee settlement.

The tale that Abraham Enloe is famous (or infamous) for claims that he was the biological father of Abraham Lincoln. The story holds that while living in Rutherford County, the Enloes took in a young woman in need of a stable home to work as a housemaid. She was Nancy Hanks. While Sarah was away visiting relatives, Abraham and Nancy conceived a child, and when Sarah discovered the pregnancy after her return, she insisted that Nancy be sent away. To keep peace in the family, Nancy was either sent to live in Kentucky with the Enloes’ recently married daughter, also named Nancy, and her husband, or taken there by a man named Tom Lincoln, whom Abraham Enloe paid to take Nancy Hanks away and to marry. Nancy named her child Abraham after the Enloe patriarch. As evidence of the likely truth of the story, some proponents note the physical resemblance between the two Abrahams: their height, deep-set eyes, and gaunt cheeks, though Enloe had striking blue eyes, not at all like the deep brown ones of the president. Genealogists have attempted to trace the president’s paternity back to Enloe and have published articles and books on the topic, though few scholars accept the story as possible.28 Academic historians doubt that this Nancy Hanks was Lincoln’s mother at all. Two important facts complicate the legend. First, Lincoln was born February 12, 1809, three years after Nancy’s transport to Kentucky; also, Lincoln had an older sister, Sarah. Finally, Abraham Enloe’s son Wesley doubted the story and could provide no evidence to confirm it.

Some scholars have suggested that the tale was spun or nurtured by Democrats or other political rivals in an effort to tarnish Lincoln’s reputation both before and after he was elected president. Even so, the legend lives on, and some descendants of Oconaluftee families defend it vigorously. Whether it remains a part of the lore as a scandal or a claim of Enloe superiority and fame, this uncertain link between the remote Oconaluftee Valley and one of the most influential leaders of U.S. history matters greatly to many. If the story lives as a point of pride, then it suggests how strongly the descendants of this mountain community want to establish their merit and mark on the national stage. Stepping back from the story, even if it is not true, Abraham Enloe achieved great success in North Carolina, not least of which can be attributed to being a parent to seventeen children—nine sons and eight daughters—and managing the farm until his death in 1841. Without the Lincoln celebrity, Enloe should certainly be viewed as the patriarch of a prosperous and large mountain family.

Perhaps a story that captures the determination and bravery of the early settlers as a group is that of Ephraim and Sophia Mingus, who homesteaded in Big Cove in the spring of 1814. Ephraim was the oldest son of Jacob Mingus and about twenty years old and newly married to Sophia Ellis. Haywood County historian Alice R. Cook honored them with the moniker “pilgrims of destiny” as they set off from the Mingus farm carrying their “bare necessities in split basket and a bag on their backs.”29 After hiking eight miles up a trail alongside Raven Fork, they found a valley and made a camp. All night while they lay on the ground, they heard “the night howl of the wolves, panther screams on the ridge, and the cry of an owl.” By the morning, Ephraim concluded that the place was too wild for them to stay, but Sophia saw that the land was rich with edible plants, tree nuts, fruits, wildlife, and fish, and she replied to his suggestion to retreat by saying, “We have come now. Can’t we stay and try out life here? It may be that we can start to live.” So the couple constructed a temporary cabin using wooden pegs, vines, and other simple methods. It had a poplar puncheon floor, which was constructed of logs halved lengthwise and set parallel with the split side up. The door was hand hewn and attached with wooden hinges and a fastener. The shakes on the roof were hand rived or split, and the chimney was built of rock using clay mortar. This precarious beginning led to success and prosperity as they ultimately acquired over 1,000 acres in the valley and raised a family of eight children.30 Ephraim and Sophia lived all their lives together in Big Cove, and Ephraim’s brother Jacob Jr. joined them, establishing his own farm nearby for two decades before moving to Missouri.31 Jacob Jr. was a preacher at the Lufty Baptist Church.

CHEROKEE “RESERVEES”

During the first two decades of the nineteenth century, the United States continued to press the Cherokee Nation for additional land cessions. Gradually, George Washington’s policy of encouraging the Indians to become “civilized” (that is, Christian, patriarchal, and capitalist owners of land as private property rather than as communal holdings) and then to assimilate into white society was replaced by the view that white society needed Indian land for its own communities, farms, and industries and that true Indians would never give up hunting and tribal warfare as occupations. Consequently, the rationale went, the eastern Indians should be removed west beyond the states’ boundaries into territories of their own for resettlement where they could continue their traditional ways of life. This view was championed by Andrew Jackson, a celebrated general from the War of 1812, who became president in 1829.

The transition from one policy to the next was gradual; during the first two and a half decades of the nineteenth century, the Cherokee Nation adapted to the demands of the federal government, communicated by Meigs, the long-time federal Cherokee agent. The most prominent and wealthy Cherokee chiefs in Tennessee and Georgia became proprietors of large farms and used slave labor. A number of them were of mixed heritage, with white and Cherokee ancestry; consequently, they learned to speak and read English. During the same period, Sequoya, a Cherokee who also went by the name of George Gist, or Guess, realized that his people needed the facility of a written language like the whites’. Remarkably, he single-handedly developed the Cherokee syllabary, which came into use around 1821. It is a system in which each syllable of the language corresponds to a unique symbol, and it was easy for those who spoke Cherokee to learn quickly and to use both for reading and writing. The syllabary enabled the Cherokees to write laws and keep records, as well as to publish a newspaper in their native language, bringing literacy to the culture with uncanny speed. Literacy provided a new kind of national pride and identity as well as the means to function as a nation-state. It is hard to overstate the adaptation and innovation that the Cherokees achieved during these years. William McLoughlin, a prominent Cherokee scholar, has termed the era a “Renascence” to emphasize how fully the traditional culture adapted to its challenges with creativity and aplomb.

The elite Cherokees in and around New Echota, Georgia, thought that the best way to protect their interests was to establish a Cherokee Nation along the lines of the representative democracy of the United States, with elected leaders empowered to negotiate on a continuing basis with the federal government. Rather than needing to call ad hoc national councils where weeks of deliberation might or might not lead to a consensus, the Cherokees created a central government at New Echota following the outlines of the U.S. Constitution with a principal chief and assistant chief, a canon of laws, and a national judiciary. In short, the Cherokees transformed themselves as the United States wished, but instead of dissolving their sovereignty into that of the nation of white settlers surrounding them, the Cherokee Nation was on its way to becoming an independent state within a state, a turn that neither the surrounding states nor the federal government wanted. Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina wanted the Cherokees’ land, and these states, assisted by the federal government, whittled away at the established boundaries of the Cherokee Nation. Most always the treaties offered the Cherokees additional annuities in goods or cash for further relinquishing traditional hunting grounds and concentrating the Cherokee people into smaller and smaller pockets of communities. Land cessions also allowed Cherokees to eliminate debt that they had accrued from the decline of the deerskin trade.32

The treaty of 1819 between the Cherokee Nation and the United States had significant consequences for those Cherokees living in the North Carolina mountains. First, it ceded all the land in and around the Smokies to the state. It provided for the federal government to pay displaced Cherokees for all improvements to their lands such as cabins, pastures, and cleared land and created a large area in the West for them to move to, if they preferred, rather than moving into the now smaller territory of the nation. But the treaty contained an important alternative for Cherokees who did not want to leave their farms: individual heads of families could apply for a reserve of 640 acres (one square mile) and become U.S. citizens, leaving the collective protection of the Cherokee Nation. Most Cherokees affected by the new cessions did not want to move west, so they moved into the new boundaries of the Cherokee Nation. But about fifty families in North Carolina applied for reserves and stayed put on their lands as established by the Meigs-Freeman line. Among these families were Yonaguska, Utsala (or Euchella), and others who had always lived along the Oconaluftee, Tuckasegee, and Little Tennessee Rivers. Reserve plots were located at Cowee, Kituwah, along the Cullasaja and Little Tennessee Rivers, in Franklin, along Alarka and Savannah Creeks, and at the mouth of Soco Creek as it flows into the Oconaluftee. In this fashion, these Cherokees became “owners,” or “reservees,” of their land, now classified as private property. According to the language of the treaty, they were citizens of the United States and, by extension, of North Carolina. But this stipulation was more in name than in practice; the reservees did not exercise voting rights and were not viewed as citizens by the whites. They lived quietly, traded cattle and sheep with the white mountain families, and sold ginseng for export, ultimately, to China for ten cents a pound at the local store owned by Felix Walker Jr., the son of the land speculator.33 Also, though the treaty stated that they would no longer be part of the Cherokee Nation, they continued to be included in Cherokee affairs and participated in the events and discussions that preceded the nation’s removal in 1838; nonetheless, as reservees, they were distinct from those living within national boundaries and were disadvantaged somewhat by their distance from New Echota. Their status was precarious, to be sure, but it provided an opportunity for a sage and determined leader to embark on a path that would keep them on their homeland.

Yonaguska, or Drowning Bear, was the most prominent chief of these Lufty Indians. According to Mooney, he was “a peace chief and counselor rather than a war leader,” so he is not named in any war treaties. He was reputed to be a persuasive and powerful speaker in town council as well as strikingly handsome. Mooney states that Yonaguska was six feet, three inches tall and “strongly built, with a faint tinge of red, due to a slight strain of white blood on his father’s side.” In 1819 he lived on Governor’s Island in the middle of the Tuckasegee River, near Ela. The federal listing of reserves states that there were sixteen members in Yonaguska’s family at this time.34 He had at least two wives, five children, and a slave, Cudjo, who was treated as a member of the family and was loyal to Yonaguska throughout his life.35 Though far too little is known about the man, several legends of his youth and adulthood suggest his unique insight and talent for leadership. Yonaguska was born in 1759, so he would have been a toddler when James Grant razed the Out Towns and a youth during the revolutionary era. During his young adulthood, he would have experienced wave after wave of land cessions. Though he advised peace and friendship with whites, he believed in traditional Cherokee legends and ways of life and resisted every inducement to move from the homelands. Mooney explains that Yonaguska thought that “the Indians were safer from aggression among their rocks and mountains than they could ever be in a land which the white man could find profitable, and that the Cherokee could be happy only in the country where nature had planted them.”36 His brother Willnotah told a story about him as a child of twelve in which he had a frightful vision of the white man’s coming to the mountains that no one believed at the time.

There is no record of the role of women among the reservee Cherokees, and that is a limitation to understanding the early decades of the nineteenth century in the valley. Scholar Wilma Dunaway has established that most Cherokee women of the day (excluding elite Cherokees in New Echota and those in interracial marriages where they had accepted a patriarchal system) continued to live in traditional ways following the practices of their matrilineal clans.37 Since the Cherokees of western North Carolina were among the most traditional of the nation, it seems quite likely that women would have been as active in their own community as they had always been in guiding the decisions that affected their households, clans, and towns. One wonders how women were involved in the actions that are today fully attributed to Yonaguska and a white man named Will Thomas.

By late in the 1810s, of course, it was obvious that Yonaguska’s early vision had been prophetic. Ironically, Yonaguska’s close relationship with Will Thomas set the reservees and other North Carolina Cherokees, who had become known as the Lufty Indians, down a course by which they saved part of their homeland for themselves and established the Eastern Band. At just the right time to put this tale in motion, in 1818, at age twelve, Thomas signed a contract to serve as store clerk for three years at the Soco Creek Trading Post, established on the southern bank of the creek by Felix Walker Jr. Will was the only son of a young widow, Temperance Thomas, and he accepted this position to begin to make his way in the world. He planned to use the one-hundred-dollar payment that he would receive at the end of his term to set himself up in business.

What can be thought about the legendary meeting and subsequent friendship of these two men, the sixty-year-old chief and the teenage apprentice clerk? Imagine the scene of a backcountry trading post alongside a beautiful creek just beyond the highest peaks of the Smokies. An everyday transaction led to an acquaintanceship, then to a friendship, and finally into a complex, multifaceted and lifelong relationship. The white youth became the champion of the Lufty Cherokees. It seems to have been one of those fateful encounters that changed history. The story goes that the chief had sympathy for Will because he was an orphan with no father or brother. Also, Will, according to all sources, was bright, curious, and welcoming to the Cherokees with whom he daily traded city goods for deer and other skins and ginseng. In time, Will picked up the Cherokee language, probably largely taught to him by a Cherokee companion in the store. Once the syllabary was introduced, Thomas also learned to read Cherokee. In a twist of fate, by the time Thomas’s apprenticeship to Walker ended, Walker was bankrupt and wanted for debts. He had nothing to pay Will—not even part of the promised one hundred dollars.

So Thomas returned to live with his mother at a farm she had bought on the west bank of the Oconaluftee near the mouth of Soco Creek. Knowing that her son must find a way to make a living, his mother sold some of her land and invested the proceeds into a store for Thomas to run as proprietor. This store, located on Thomas land, was named Qualla, after a Cherokee woman named Polly. It was also known as Indiantown. Eventually, Walker wrote to Thomas, apologized for cheating him, and sent him his law library as substitute compensation for the apprentice’s years of labor. Given Thomas’s intellect and drive, he set about reading the law books and considered that in time he might be able to practice law. Just about this time, in early 1821, Yonaguska persuaded the Lufty Cherokees to accept Will into the tribe as Wil-Usdi, “Little Will,” with Yonaguska taking the role of maternal uncle and thus giving him an identity within the tribe. To Thomas the relationship came as a surprise, but likely it was a welcome one that bound him to the Cherokees he knew and regularly encountered in his store. Having no experience in a matrilineal clan, Thomas may have thought of Yonaguska as an adoptive father, rather than an uncle. By 1822, Thomas was set up in business for himself and operated using a generous trading policy with both whites and Cherokees. His records are full of notes of debts between individuals and receipts of goods bought on credit until harvest or some other form of exchange, such as manual labor, allowed buyers to clear their tabs.

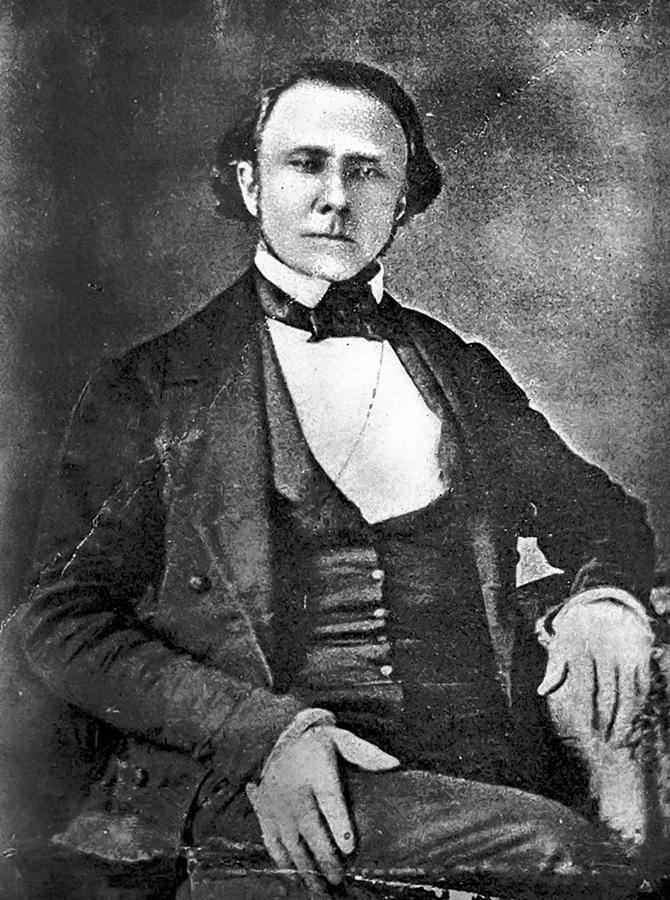

Col. William Holland Thomas, 1858.

COURTESY OF THE STATE ARCHIVES OF NORTH CAROLINA, RALEIGH.

MOUNTAIN FAMILY PROSPERITY AMID CHEROKEE ANXIETY

Unfortunately, the reserves did not end land disputes for the Cherokees. In the hurry to claim newly ceded lands, the state mistakenly sold some reserves to white families, who then occupied portions of them. In 1824 both Utsala (Euchella) and Yonaguska filed suit against whites who had deeds to their reserves. Euchella v. Welsh was the first case to come up in the Supreme Court of North Carolina. With Utsala represented at the federal government’s expense, the court upheld his right to his reserve. Because the land had already been sold to whites, however, the state offered him new territory as compensation. Yonaguska’s case was similar to Utsala’s, so it was dismissed with the same ruling. In August, the state offered to buy out all of the Cherokees who owned reserves. The process took several years but was completed in 1829, when Congress provided North Carolina $20,000 to cover the land purchases. Utsala moved back into land controlled by the Cherokee Nation, but Yonaguska and many of the other reservees moved to Quallatown, creating for themselves a Cherokee community that was separate from the Cherokee Nation but one in which the residents held their land in common as a means of protection against encroachment. This new settlement at Qualla was the beginning of the Lufty Cherokees as legally distinct from the Cherokee Nation. Eventually, the group, supervised by Yonaguska, built a council house on Soco Creek as their community center.38 The experiment of having Cherokees become private property owners was short lived, and in time it became clear that communal ownership was a far better strategy to protect their land rights and community. Because the Cherokees were unschooled in the state’s legal system, individually held private property left them too vulnerable to the whites. They had been “imposed on, cheated, and defrauded by some of the people of this country,” so in 1829 the Lufty Indians hired John L. Dillard as their attorney.39 This job was handed over to Will Thomas at age twenty-six in 1831, and he remained their counselor and agent until after the Civil War.

During the same decade the Lufty Cherokees determined that another cultural practice of the whites, drinking alcohol, was not for them. The Cherokees had imbibed since the beginning of the deerskin trade, when rum became widely available. Some, including Yonaguska, became addicted. At one point the chief became severely ill and fell into a trance. Though he seemed dead except for his breathing, he was carefully attended by his family. Yonaguska at last awoke, after either twenty-four hours (according to Mooney) or two months (according to Willnotah, Yonaguska’s brother). Mooney’s account states that during the trance “he had been to the spirit world, where he had talked to friends who had gone before, and with God, who had sent him back with a message to the Indians, promising to call him again at a later time.” The experience motivated the chief to renounce liquor for himself and discourage it among his people. Once recovered, he made a moving speech to the town council and “declared that God had permitted him to return to earth especially that he might thus warn his people and banish whiskey from among them.”40 The chief then asked Thomas, who was present in the council, to write a temperance pledge, which Yonaguska signed first, followed by the members of the council. This pledge significantly decreased the Lufty Cherokees’ use of alcohol, a fact that helped make them tolerable to nearby whites. In the coming years when Thomas fought for the Lufty Cherokees’ legal status, he often used their sobriety as an example of their virtue.

Meanwhile, the mountain families in the valley prospered. Their families grew and expanded their farm acreage and operations. The community as a whole undertook projects to establish infrastructure and strengthen their community bonds. One such effort was to improve an existing trail over the crest of the Smokies into a road that could accommodate travelers, wagons, and livestock drives to Tennessee. An existing ancient trail, Indian Gap Trail, crossed the crest at Indian Gap, which is about a mile west of Newfound Gap as the crow flies. This trail linked the Great Indian War Path in East Tennessee with the Rutherford War Trace in western North Carolina. It ascended the Tennessee side of the mountains along the west prong of the Little Pigeon River, passed through the gap, and descended Beech Flats Prong, which becomes the west fork of the Oconaluftee River, and followed it to Whittier, North Carolina.41 Unlike the current Newfound Gap Road (Highway 441), this trail ran on the north side of the river, though both routes follow the river’s slope downhill. As early as 1826, the Haywood County Court ordered a group of valley settlers to “view and mark out a way for a wagon road,” naming Ephraim Mingus, Samuel Conner, Jonas Jenkins, Rafe Hughes, Jacob Stillwell, Abraham Enloe, Aseph Enloe, George Shuler, Nathan Hyatt, and Samuel Sherrill as partners and workers. Though it is difficult to determine with confidence, a few enslaved individuals may have contributed labor to this project. The 1830 census shows that George Shuler, John Mingus, and Abraham Enloe owned a total of five enslaved males at this time, so these men may have been tasked with some of the immense physical labor that would have been required.42 It appears that progress was slow until 1832, when the North Carolina legislature chartered the Oconalufty Turnpike Company to build a road from the gap down to John Beck’s farm just below Bradleytown, the area that became Smokemont. The named commissioners of this company—Abraham Enloe, Samuel Sherrill, John Carroll, Samuel Gibson, and John C. Beck—were empowered to raise stocks to finance the venture. Once complete and “received” by appointed Haywood County officials, the company could charge tolls for those using the new road. These tolls were set:

|

4-wheel carriage of pleasure |

75 cents |

|

Gig or sulky |

37 1/2 cents |

|

6-horse wagon |

75 cents |

|

5-horse wagon |

62 1/2 cents |

|

4-horse wagon |

50 cents |

|

3- and 2-horse wagons |

37 1/2 cents |

|

1-horse wagon or cart |

25 cents |

|

Horse without rider |

2 1/2 cents |

|

Head of cattle |

2 cents |

|

Hog or sheep |

1 cent |

|

Traveler on horse back |

6 1/4 cents43 |

Also at this time, Jacob Mingus was made overseer of a road from his home to Abraham Enloe’s, quite possibly a segment of the turnpike project.44 It seems likely that the commissioners invested in the road, but Will Thomas did, too, and became an enthusiastic proponent of it. In June 1839, Thomas wrote to James S. Porter of Sevierville, Tennessee, asking him to “encourage your people to complete their part of the Smoky mountain road” and promising to work to extend the North Carolina part into South Carolina. By September he was able to write business associates that the road had been received by Haywood County as complete, that he expected to make a settlement on it with the state treasurer in Raleigh, and that Robert Collins should collect tolls and keep the road in repair.45 A statement from his Quallatown store shows that he had invested $2,417.47 on behalf of his firm, which by then included a handful of stores and several business partners.46 Collins managed the road and took tolls, as shown in an existing record book for the month of June (year unknown), naming the person or number of livestock heads, including hashmarks counting each animal, and listing a total fee paid to the company. Though worn and difficult to read, this “Road Book” shows that business was steady.47

During the 1830s, the mountain families embarked on several additional community and entrepreneurial projects that served to make life in Oconaluftee Valley more manageable than it had been when every farmer had to be entirely self-sufficient. The area became an election precinct in Haywood County in 1831.48 In 1834, a man named Couch began operating a gunpowder mill at the confluence of Couches Creek and the river.49 Three years later Ephraim Mingus visited Alum Cave for the first time, perhaps led there by Yonaguska, though the timing of such an event makes it doubtful. Mingus, along with Robert Collins and George W. Hayes, surveyed the area, and bought a fifty-acre tract to create the Epsom Salts Manufacturing Company to mine alum and saltpeter up to and through the Civil War. The business was successful enough to employ others, who lived in camps. Some of the laborers are likely to have been men enslaved by the businesses’ owners. The company came to be jointly owned by the three Mingus brothers (Ephraim, John, and Abraham), Robert Collins, David Elder, Micajah Rogers, and Ira H. Hill.50

“FELLOWSHIP FOUND”

The Oconaluftee mountain families also reached critical mass by the late 1820s to establish community worship services. The Reverend Humphrey Posey and Adam Corn established the Mount Zion Church in 1829. Throughout his life, Posey was associated with Baptist efforts to bring Christianity to the Cherokees; around 1820, he created a mission school for the Cherokees at Mission Place on the Hiwassee River, seven miles above Murphy, North Carolina. When the missionary school was not in session, Posey traveled the mountains as an itinerant preacher in both white and Cherokee villages.51 He also established white churches at Cane Creek in Buncombe County and Locust Old Fields in Haywood County.52 The first Lufty church met near Bradleytown, close to where the Smokemont Baptist Church was later built. Longtime residents such as the Minguses, Conners, and Becks attended.53 By 1836, church members decided that they needed to change the location of services because of difficult traveling conditions, presumably due to a lack of bridges to make access possible. The meeting minutes read:

The Church at Lufty

Being organized for the first time at Dr. John Mingus’; June 19, 1836—resolved that we have our church meeting at Samuel Conners & Jacob Mingus’. … Each one in their turn. For the convenience of the aged & infirm until we get a regular meeting house and that we have a prayer meeting at Brother S. Conners & Brother Mingus’ on each fork of sd. river Between each monthly meeting. Each one in its turn. Then appointed the fourth Sunday in each month and Sateray before for our church meeting days then organized.54

The alternate-site meeting arrangement was short-lived. By September 1837, the two units recombined and met in an old schoolhouse on John H. Beck’s land below a bridge. At this time the name of Lufty Baptist Church was adopted, and the members convened at this location until late in the nineteenth century. Several efforts to site and build a new church were begun throughout the next several years, but none of these early efforts succeeded.55

There were twenty-one charter members of Lufty Baptist Church. Robert Collins and Ephraim Mingus were elected to serve as deacons, and the pastors were the Reverends Adam Corn and David Elder. Elder kept the records as “moderator” during this period, including an entry summarizing the highlights of each meeting. These highlights noted appointments to the larger Baptist association, occasions when new members were received, requests for letters of “dismission” when members moved away, baptisms, and occasionally entries about a brother who “acknowledge[d] himself guilty of intoxication and made satisfaction.” One source indicates that Jacob Mingus was one of the members who made this confession and that he did so while his son served as a deacon, which may have been mildly scandalous because the by-laws prohibited “any member from making or selling spirituous liquors or from using them as beverages.” Despite these occasional moments of tension, every monthly entry declares “fellowship found,” a comment that emphasizes the important communal role of the church in the sparsely populated valley where church meetings brought people together only once a month.56

The church board functioned like a court or grievance council for small civil matters. Charges included “telling falsehoods, gossiping, stealing, playing cards, drinking, profanity, general misconduct, and causing strife in the family to more serious sins of the flesh. Some of the brethren and sisters became stricken with ‘disorders of passion.’” Members could be dismissed or excluded from the church if infractions were serious or if they refused to explain the charges. If a member was “churched,” he or she was removed from the church. On occasion, outside ministers came to serve as impartial judges. “Habitual offenders” could be put under “watch care” of other members.57

At about the same time, in 1830, a Cherokee Methodist mission was established at the foot of Hughes Ridge, which forms a divide between the Oconaluftee and Raven Fork. The preacher and teacher of this log church was William Hicks. In addition, a circuit rider preacher, David Woodring, served the valley. He was sometimes called David Ring by mountain folk.58

The success of the Methodist mission is impressive, given Yonaguska’s suspicion of all missionaries. When a Cherokee translation of the Gospel of Matthew arrived in North Carolina, he insisted that it be read aloud to him before it could be read to his people. Mooney’s account states that “after listening to one or two chapters the old chief dryly remarked: ‘Well, it seems to be a good book—strange that the white people are not better, after having had it so long.’”59 Even so, Thomas encouraged Christianity among the Cherokees, seemingly for the same reasons he encouraged temperance: to assure the whites that the Lufty Cherokees were model residents. In some ways, the total immersion baptism practices of the Baptists were familiar and appealing to the Cherokees because this ceremony resembled their own Going to Water purification practice, which was regularly observed for such purposes as celebrating seasonal renewal and as ritual cleansing before warfare or its substitute, the ball play.60 This resemblance generally made the Baptists more appealing to the Cherokees than the Methodists, though the Methodists were especially influential in western North Carolina.

The white mountain families and Lufty Cherokees managed to live side by side in the valley with apparent neighborliness during the first decades of the nineteenth century, possibly because of the Cherokees’ impulse toward harmony and nonconfrontation. Both were active in trade and in efforts to strengthen their own largely separate communities. But their lives were controlled by distinct priorities. While landowning white farmers were busily establishing themselves, producing surplus goods, and building a road to get them to market, the Cherokee experience of living within the young United States was dominated by scrambling to hang on to their land and culture despite all manner of intrusions. Clearly, individuals from the two groups did forge important bonds, best exemplified by Yonaguska and Will Thomas. It is also clear that unease and distrust were as likely to be the sentiments between the groups as tolerance and cooperation. For many of us today, this frontier era has a romantic character, full of potential and mystery. The natural beauty of the land must have been astonishing and its wildness more intense than ever since, regardless of the many decades of Cherokee residence that had already transformed the land. So much about the thoughts of the valley’s people during this time can only be left to musing, musing at once irresistible and unanswerable.