Chapter 6

BEGINNING TO MAP THE SMOKIES

FAMOUS MEN AND MOUNTAIN NAMES

▲ ▲ ▲

I know it’s unwise to hike alone, and I do it rarely. Don’t tell my family. But from time to time I set out by myself, and I enjoy it because when I’m alone there’s no reason to talk. I notice more things. I detest a crowded trail; I’m most content when a few other folks are passing me or coming from the other direction. I am aware that the park is bear country. I have a plan if I meet a bear: keep car keys, ID, and phone separate from the day pack; blow my whistle when it gets really quiet so as not to surprise the bear; if approached, toss the pack with my lunch to the bear; back away slowly. (A friend of mine once encountered a bear on Spence Field and handed over his pack containing peaches, a move that ended the meeting.)

The bigger risk is getting lost or confused. My security is placed in the detailed trail map in my day pack. I’ve studied it beforehand, too. On occasion, I have missed a turn; I have inadvertently taken the wrong trailhead and thought I was on a different path than I actually was. It does not take long for the beauty of the woods to become terrifying once I feel I’ve made a mistake. At these times, I force myself, despite my elevated pulse, to stop, take out the map, check it, retrace my steps. I check my watch for how long I have been hiking and when I passed the last junction. I ask other hikers about the trail; I don’t care if they think I’m stupid or annoying. Nothing new there.

I consider maps to be the ultimate sign of human intelligence. They are similar to the wonder of a hardware store that has the precise tool, among thousands, to solve my particular problem, a tool made by people who anticipated my need. I love that. Today, maps are ubiquitous and reliable, on our phones, in our hands, ready to assist. We take them for granted until the GPS signal is lost. What must tramping in the Smokies have been like when one had only an animal path, unmaintained trail, compass, or part-time guide? The glorious technology of a good map makes it possible for people to be in and move through the woods, and I am grateful to those who made them.

▲ ▲ ▲

DESPITE THE ISOLATION of the Smokies, reports of the mountains’ height and ruggedness had piqued the curiosity of botanists and geographers, who were beginning to conduct serious scientific studies of the mountains in the middle of the nineteenth century. The geographers focused on mapping the area, describing its most important features, and accurately measuring the altitude of the dominant peaks. Challenges lay in access to remote areas without roads and in using the instruments of the day, namely the cumbersome mercury barometer that was dependent on air pressure. Measurements from this instrument varied throughout the day and, of course, with changing weather.

In the summer of 1858, Thomas Lanier Clingman led a party of six to a number of the peaks in the Smokies. By this time Clingman was an explorer, scientist, and politician, holding one of the U.S. Senate seats for North Carolina. Clingman already had quite a reputation for exploring. Previously, he had been engaged in a contest with a former professor of his at the University of North Carolina, Elisha Mitchell, to determine the highest peak east of the Mississippi River. Mitchell and Clingman had both measured the mountain that was the winner, located in the Black Mountains of North Carolina. But while verifying earlier measurements, in 1857, Mitchell accidently fell from a cliff above a waterfall and drowned. Subsequently, his name was given to the mountain both Mitchell and Clingman had championed and where Mitchell lost his life. Mount Mitchell is 6,684 feet high.1

An Asheville resident, Clingman was also a great promoter of the western Carolina mountains. The group he led to the Smokies in 1858 included Samuel Leonidus Love, a prominent physician and political figure of Waynesville, North Carolina, and Samuel Botsford Buckley, a geologist and naturalist who became the state geologist of Texas after the Civil War.2 This group traveled to the crest of the Smokies through Oconaluftee Valley, and Buckley conducted barometric measurements, though they would not prove accurate in the long run. He also named a number of peaks, including Mount LeConte and Mount Guyot. The former was named for one of the Le Conte brothers, either Professor Joseph Le Conte, who was a prominent geologist but did not work in the Smokies and seems never to have visited them, or his older brother John Le Conte, a physician and professor of chemistry, physics, and natural history. The story justifying John as the namesake is that he took comparative barometric readings from Waynesville when Buckley did so from the Smokies. Buckley named Mount Guyot for the eminent Swiss geologist Arnold Guyot, whom he knew and with whom he had previously explored other parts of the southern Appalachians—though not the Smokies—in 1856.3

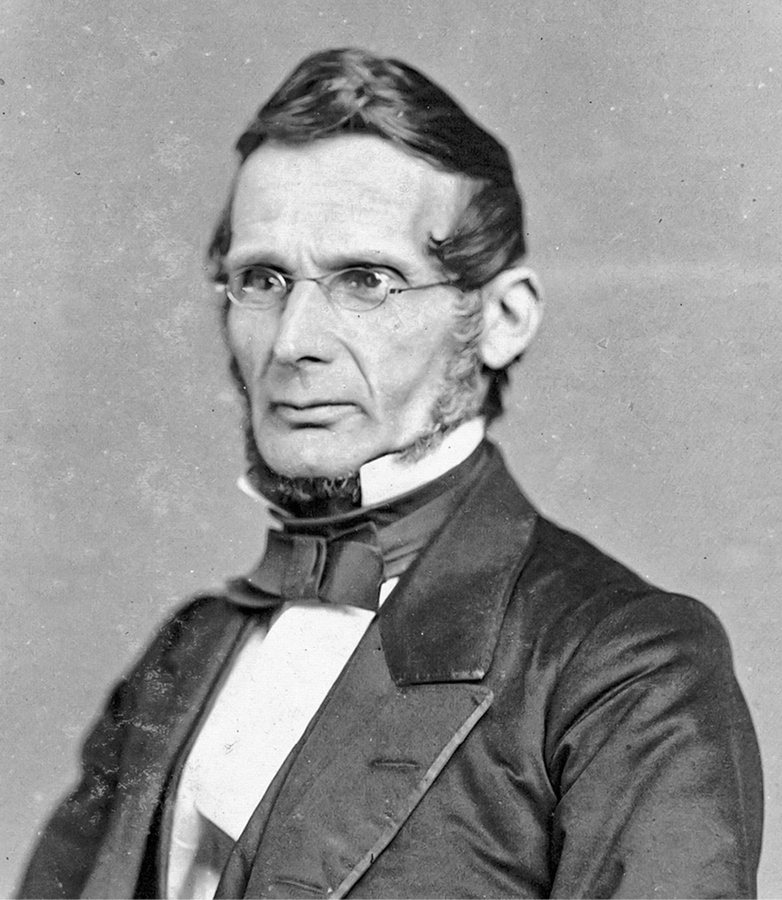

By 1859, Guyot himself was prepared to explore the Smokies, which he described as the “master chain of the Appalachian System.”4 With funding from the Smithsonian Institution and planning support from Clingman, Guyot spent the summer traversing the entire fifty-mile crest of the Smokies and taking more accurate measurements and making more systematic records and maps than had ever been done previously.5 Guyot was a lifelong friend of paleontologist Louis Agassiz, who discovered the effects of Ice Age glaciation in the northern hemisphere. He had followed Agassiz to the United States once his employer, the Academy of Neuchâtel, closed because of war. Guyot’s talents were soon recognized, and by 1854 he was chair of physical geography at Princeton University. He launched a study of the Appalachian chain in 1848 and turned his attention to the southern section in 1856, spending three additional summer vacations on this project: in 1858, 1859, and 1860.6

Clingman arranged for Robert Collins to serve as Guyot’s guide for the 1859 expedition and, beforehand, to clear a six-mile horse trail of sorts to the highest peak, then called Smoky Dome by mountain folk. Cherokees knew the place as Kuwahi, “the Mulberry Place.” This was the mountain under which the legendary White Bear of the Cherokees had his council house. No doubt by this time Collins was well known as the mountain guide of choice on the North Carolina side. During what Guyot described as “the remarkable rainy season” between late June and early August, he and Collins, along with one or more of Collins’s sons, “camped out twenty nights, spending a night at every one of the highest summits, so as to have observations at the most favorable hours. The ridge of the Smoky Mountains I ran over from beginning to end, viz: to the great gap through which the Little Tennessee comes out of the mountains.”7 Historian Paul M. Fink insightfully imagined the immense difficulty and achievement of Guyot’s work:

Arnold Henry Guyot.

COURTESY OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, N.J.

To one who has pushed his way through the jungle-thick vegetation of the more remote parts of the Smokies, even in this late day (1938) when trails of a sort exist, there can be no more striking illustration of the zeal that actuated this great explorer than a mental picture of him, with but a single companion, struggling up the steep, trackless, laurel-tangled slopes of Smoky, burdened with supplies for a week or more, and handicapped still further by a bulky, fragile barometer, that must be carefully protected from any rude contact that might wreck beyond repair its delicate mechanism. But though laboring under such difficulties, so painstaking was Guyot with his observations and subsequent calculations that the figures he cites for the various points in the Smokies seldom vary as much as a score of feet from the latest altitudes announced by the United States Geological Survey.8

Though a number of his names were later changed, Guyot named the triad of peaks around Smoky Dome: Mount Buckley, Clingmans Dome, and Mount Love. The first was to honor the efforts by Samuel Buckley the year before, a return compliment. The last was to recognize Col. Robert G. A. Love, who “kindly loaned” him the horse that was the first to ascend Clingman’s Dome by way of Collins’s path. And, of course, the dome, the highest peak in the park, was named for Clingman out of gratitude and acknowledgment of his previous exploring but also because Guyot claimed that that name was already in current use. Even though it appears that Buckley had first named Clingmans Dome after himself, in a letter to the Asheville News explaining his choices, Guyot said, “I must remark that in the whole valley of the Tuckasegee and Oconaluftee, I heard of but one name applied to the highest point, and it is that of Mount Clingman.” Consequently, the highest peak in the park, at 6,643 feet, has carried Clingman’s name though the tribal council of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians passed a resolution in July 2022 to return to the Cherokee name.9

Other mountains that retain Guyot’s appellations are Luftee Knob, the Sawteeth, and Tricorner Knob. In addition, Guyot called the gap to the east of Indian Gap (where the original turnpike traversed the crest) New Gap, which was the basis for its current name, Newfound Gap. Also, Guyot recognized Collins’s help by naming for him the peak whose name was later changed to Mount Kephart. This appellation honored twentieth-century writer and key park proponent Horace Kephart. Ironically, when Kephart learned that the mountain was to be named after him, in 1928, he wrote to the chairman of the nomenclature committee explaining that he would instead prefer the mountain at the head of Deep Creek to bear his name, because he had lived on Deep Creek and because Tennesseans were upset that a mountain they already knew to have a name that honored someone with Tennessee ties (Collins) should bear a North Carolinian’s name. But Kephart’s preference was not followed. To the contrary, Kephart’s preferred peak was named for Collins. Apparently, when someone names a mountain after you, you should not quibble about which one it is.10

Guyot was systematic and thoughtful in all areas of his work. He articulated a sensitive and reasonable philosophy for which names should prevail when multiple names for the same location were in use. Of course, this situation was much the case in the Smokies. He advised that “the name which appears the most natural or more euphonic” was the right choice. Further, he said, “When the choice lies between the name of a man and that of a name which is descriptive and characteristic, I should choose the latter.” Finally, names used by residents should be accorded “priority,” rather than those applied by scientists. These rules do seem sensible, so it is curious that the names of the key peaks of the park, some of which already had names, were indeed changed by scientists for their own memorialization. Even though Mount Guyot—the second highest peak in the park at 6,621 feet—was named the year before the Swiss geographer arrived in the Smokies and applied by fellow scientist Buckley, Guyot let the name stand. This peak had been formerly known as Balsam Cone and Balsam Pine; the Cherokees called it Sornook.11

After his return to Princeton, Guyot wrote a detailed manuscript about his work in the southern Appalachians, “Notes on the Geography of the Mountain District of Western North Carolina,” which he sent to the superintendent of the Coast Survey in Washington, D.C., in 1863. However, it was never published and apparently was filed away in the library of the Coast and Geodetic Survey for many years.12 It contained precise descriptions of the watersheds, ranges, and transportation routes in, around, and through the Smokies. For example, Guyot saw the Smoky Mountains as an “almost impervious barrier between Tennessee and the inside basins of North Carolina.” As for the hard-won and vital Oconalufty Turnpike, he commented: “Only one tolerable road, or rather mule path, in this whole distance is found to cross from the great valley of Tennessee into the interior basins of North Carolina—and the road reaches its summit, the Road Gap, as it is called, at an elevation of not less than 5,271 feet. It connects Sevierville, Tennessee with Webster, Jackson Co., North Carolina, through the vallies of Little Pigeon and Occona Luftee, the last of which is the main northern tributary of the Tuckaseegee.”13

Guyot also provided a scholarly view of the forests of the Smokies during this era, a place that was not affected by glaciation and had not yet seen commercial logging:

The forests, which, with the exception of a few spots, cover almost the totality of that mountain region, are truly magnificent, especially near the foot of the hills where humus has been accumulated by action of the water. The trees there are from 80 feet and upwards, and 8 to 11 nay 12 feet in diameter are no great rarity. The Oak, the Chestnut, the tulip-tree, the wild cherry, over 60 ft. high, with beautiful straight stems, the Magnolias and the Hickory compose the bulk of these immense forests and cloth with a foliage of perfect beauty the Mountain slopes up to 5,000 and 6,000 ft. Beyond 6,000 ft. the dark Balsam fir or its allied species the Fraser pine crown with black caps all the summits which rise beyond that limit.14

Of the Oconaluftee River, he says, it “is mostly a wild mountain torrent. Its two main sources rise at the Road Gap in the Smoky Mt. and at the Luftee Knob, in the corner formed by the Great Smoky and Balsam Mts. The whole basin is a bed of mountains which are the high spurs of the Great Smoky.” The valley provides “beautiful and fertile though narrow flat bottoms.”15

The report’s conclusion, interestingly, highlighted the relevance of Guyot’s work to Union strategy during the Civil War, which was, of course, ongoing by 1863. The roughness of the country and the limited access to it became considerations for the placement of troops:

An Army settled in the large and fertile Valley of east Tennessee where it can be abundantly provided, can easily occupy by very moderate forces, all the mountainous region, and all its available passes, across the Blue Ridge, and thus keep as it were, the keys of the doors to each of all the Southern States just mentioned. It can thus threaten from within, every one of those States and their Capitals, keep at bay any opposing forces, in the low country, and prevent their being concentrated.—It cuts in two the Confederacy from east to west.16

And the final paragraph provides an excellent analysis: “In time should the rebellion be ever overcome in the lower country, the occupation of that mountain region will, to a great extent, prevent its leaders from the possibility of taking a refuge in it, and from thence indefinitely prolonging a defensive if not an offensive war.”17 Because the manuscript was stashed away, whether it influenced any of the actions of the Union troops cannot be known. However, some Confederates also recognized the military potential of the mountains and the importance of the passes. One of the leaders who reached the same conclusion was none other than Will Thomas. These early scientific explorations reveal, yet again, that the mountains and even Oconaluftee Valley in particular were of interest to international, national, and regional leaders, well worth study and professional attention.