Chapter 8

SEPARATE REALITIES

RACE AND LAND OWNERSHIP

▲ ▲ ▲

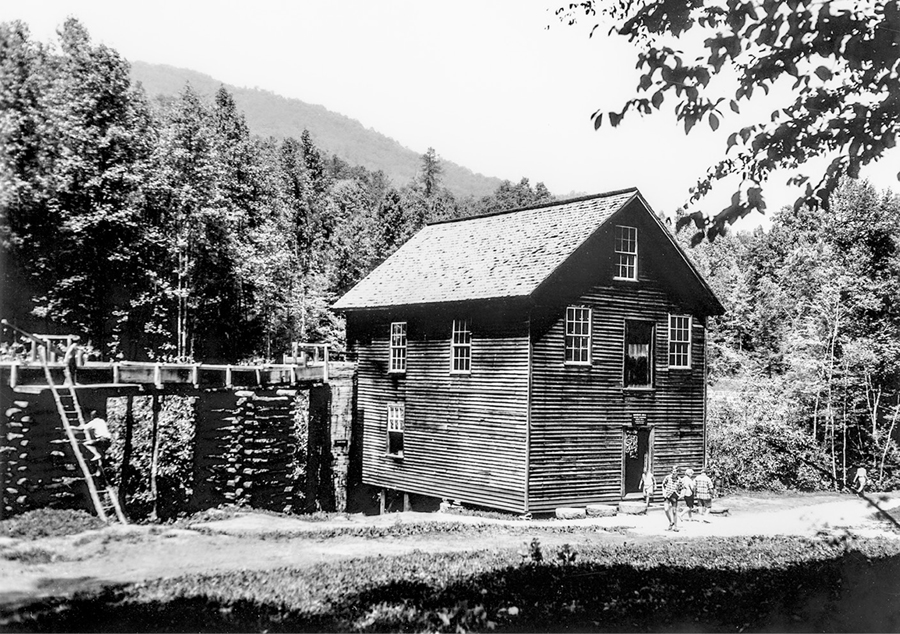

One of the best-known historical structures of the valley, and even of the national park, is Mingus Mill. A sign for it appears shortly after I exit the Oconaluftee Visitor Center and head up Newfound Gap Road toward the crest of the ridge. I take a left and park. I’ve been there all seasons, and it’s usually busy. It is this summer day. The mill building and race are the main attractions, and they merit the stop. Today the building is open. Attendants are grinding corn and giving tours, explaining the works. The process is relatively straightforward, but the mill’s design is ingenious. I understand why the building has been rebuilt, reconditioned, and maintained so well for so long. My favorite detail: the initials of the builder, Sion T. Early, etched into the outside wall, just below the peak of the roof. He was proud of his work.

So much is known about this place. Its story is documented, published, and advertised, appreciated. It represents a big achievement by a prosperous family and one that served the community, the kind of history that’s recognized, accessible, and official—appropriately so.

Without a sign, on the opposite side of the parking lot, and up a steep path, I find a cemetery in a rectangle of land. Few folks join me here. On the Smokemont 7.5 quadrangle map of 2016, the location is named the Enloe African Cemetery. Because the vegetation is trimmed, I can count at least eight mounded gravesites. Some have fieldstones to mark the head and foot, though none is engraved. Who were the people interred here? No one knows for sure. Very likely they were people owned as slaves by the Mingus and Enloe families; this was their land. Some of these people may have supplied labor to build the mill, but their initials are not etched anywhere. Neither their work nor their lives are memorialized. Perhaps the absence of a sign protects a vulnerable place—though I’ve recently read that a marker is planned. In any case, the site tells me that I cannot provide a satisfactory account of them. I must be grateful that a memory of them can be read from the land itself.

Absences, limitations, and unanswerable questions obstruct the pursuit of an inclusive history of the valley—especially for those who did not own land and were not white. I have searched records for hints, but I cannot learn much, most times, about their lives. I must accept that I cannot construct a truly equitable history even if I try, even if I include every mystifying detail I discover. Often the details do not fit together. Consequently, I share the names and accounts that I do know. Doing so, I hope, will acknowledge—and cause me to remember—the story’s incompleteness.

▲ ▲ ▲

TO THE FEW TOURISTS who visited Oconaluftee Valley in the years following the Civil War, the scars of the struggle may not have been immediately visible. In letters and published accounts, the travelers described a distinctive mountain community set in a lush, fertile landscape. Wilbur G. Zeigler and Ben S. Grosscup characterized the scene in Heart of the Alleghanies, a travel narrative published in 1883: “The waters of the Ocona Lufta, even at its mouth in Tuckasege river, are of singular purity, and through some portions of its course, from racing over a moss-lined bed, appear clear emerald green. Above the Indian town the valley grows narrow, and prosperous farmers live along its banks. The forests are rich in cherry and walnut trees, and all necessary water power is afforded by the river. Joel Conner’s is a pleasant place to stop.”1

Nonetheless, Oconaluftee families did suffer gravely from the war. By the end, nearly every family had lost someone, and most endured privations of war or direct losses from bushwhacker and deserter raids. Edd Conner, a grandson of Ephraim and Sophia Mingus, was born during the war. Later in life he recalled the Reconstruction period as “close time’s for all to live” when families had to rebuild homes and farm buildings, recover from or endure physical injuries and hardships caused by the war, cope with hunger and privation, manage without goods from outside merchants, and work tirelessly to “drive poverty from their door’s.” Conner described farmers working all day and then making and repairing shoes by “pine-torch held by some member of the family until mid-night or after” and using maple sprigs for the task.2

Mingus Mill.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

Enloe Enslaved Cemetery.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

In a few seasons, white mountain families rebounded and the community rebuilt and expanded. The lives of their few emancipated slaves are far harder to trace; some seem to have stayed for a while, and a very few of these prospered; some left, and of these people not much is known. Recovery was far slower for the Cherokees both within the township and in the Qualla Boundary. In the 1870s, Oconalufty Township, including Big Cove and Bird Town, was a community of families connected by marriage, longtime familiarity, neighborly bartering of goods and services for farm and construction labor, and shared faith. By 1880, it contained 68 households or farms and 186 families, 85 of them Cherokee, and 6 Black, in addition to 1 mixed-race couple.3 Some big families saw their children leave the area while others married, stayed, and grew even larger with more and more complex connections to one another. Some new families moved in. A couple of these had the means to buy bottomland. For instance, several Queen brothers bought land from North Carolina to establish homes in Oconaluftee Valley, one of which was a large home where Smokemont is today; others bought upslope on rockier, steeper tracts; and some scraped by as farmhands, sharecroppers, or squatters.

Residents’ circumstances varied considerably. The oldest and most established white families, like the Enloes and Minguses, owned the most fertile land and largest farms on the floor of the valley. Now in their third and fourth generations in the valley, these families were prosperous, had built comfortable homes, and had some access to larger population centers when they took livestock and the surplus harvest to market. Zeigler noted these in his travels: “Fine farms of rich black soil lay on the either side between the river and the environing mountains, which grew higher, steeper, wilder and closer together as we advanced. The farm houses were large, looked old fashioned in their simple style of architecture, ancient with their gray, unpainted exteriors, but homelike and cheerful surrounded by their large, blossoming apple orchards.”4

Other white families, such as the Conners, Becks, Bradleys, and Carvers, were also well established but placed a bit higher up the valley along the river’s terraces. These upslope families made do with marginal land and an abundance of resourcefulness, optimism, and hard work. Over time they gained a level of comfort and affluence as they purchased additional land tracts, brought in good harvests, and cultivated multiple sources of income through beekeeping, orchards, livestock, and handcrafts. New families, the McMahans, Treadways, Parkers, and Matthewses, also moved in and pursued this model.

Because there are few diaries and letters from this period, the picture of family life is episodic and omits many. The white male heads of the prosperous households were literate, but few women, poorer white, Black, or Cherokee people could read or write. Consequently, little information about the lives of women and freed slaves exists. This situation differs somewhat for the Cherokees, whose stories are chronicled from the point of view of a traveler, a government official, or, later, Cherokee ethnologist James Mooney. Among all the mountain families, some names and dates are available in records, but they supply little insight into individuals’ struggles and joys. A travel account by Rebecca Harding Davis published in Lippincott’s Magazine in 1875 includes a bit of detail of women’s home life. She visited the home of a Colonel P., whom she identified as the only white farmer in Qualla, the Cherokee homestead:

Colonel P’s mansion is a huddle of log-built rooms, chunked with mud, squatted in the middle of cornfields which his wife has helped to plough. She weaves on a heavy homemade loom the clothes of the household, waits on her husband and sons at table, and eats herself with the servants, white and black. She is a shrewd, clean-minded just woman, bony and gray-haired, dressed, like her cook, in brown linsey, with a yellow handkerchief knotted about her neck. Her comfortless house was as clean as a Shaker’s, and her table bountifully spread. It was not the custom of wives to join in the conversation of their husbands and other men.5

Still farther upslope were the “branch-water people” who tended rock-rich land that they may not have owned.6 From year to year their lives were precarious. To make ends meet, they might have hired out as laborers to their more prosperous neighbors. Toward the end of the century, they might have left the valley periodically to work building railroads, on logging teams, or in timber mills. Davis also provided a glimpse into the situation of the poorer mountain people who “live in unlighted log huts, split into halves by an open passage-way, and swarming with children, who lived on hominy and corn-bread, with a chance opossum now and then as a relish.” She explained,

They were not cumbered with dishes, knives, forks, beds or any other impedimenta of civilization: they slept in hollow logs or in a hole filled with straw under loose boards of the floor. In these villages we found thoroughbred men and women, clothed in homespun of their own making, reading their old shelves of standard books: they were cheerful and gay, full of shrewd common sense and feeling, but utterly ignorant of all the comforts which have grown into necessities to people in cities, and of all current changes in the modern world of art, literature, or society: in fact, almost unconscious that there was such a world. Among the mountain-woodsmen we found other men and women who had never learned the use of a glass window, or a cup and saucer, and manifestly never learned to keep themselves clean; yet they were of honorable, devout habits of mind, and bore themselves with exceptional tact and delicacy of feeling and the dignity and repose of manner of Indians.7

Yes, there was the road, the Oconalufty Turnpike. It linked Sevierville, Tennessee, with the valley and other areas of Swain and Jackson Counties in western North Carolina. Shortly after the end of the war, in October 1865, former Confederate colonel Will Thomas led the effort to remove the barricades that his men had placed to block the road to slow and frustrate Union soldiers and renegades. His goal was to make it usable for wagons quickly, presuming the resumption of overmountain traffic and trade.8 But its condition was miserable. When millwright Sion Thomas Early and John McMahan, who was helping him, needed to bring tools and equipment over the state line to work on a new mill on the Minguses’ property, the “road was so rough that it was necessary in some places to jack the wagon up with poles in order to get it over boulders and other obstructions, in other places it was necessary to cut logs and chain them to the wagon to act as a brake when going down steep grades.”9 On this trip the men were also tracked by a panther that abandoned them as potential prey only after hours of stalking and emitting three blood-curdling screams from a perch above their evening campfire.

So the valley, while not entirely isolated, remained remote and untamed until late in the nineteenth century. The white, Black, and Cherokee residents lived as neighbors throughout the era, but they faced different challenges, a fact that separates their stories. White farm families concentrated on cultivating their farms and shoring up their economic security while enhancing, when they could, their community with a school and permanent church building. Emancipated slaves either stayed as paid tradespeople or laborers or left to seek livelihoods elsewhere. The Lufty Cherokees faced another round of existential challenges in the forms of smallpox and flu epidemics, multiple changes to their legal status in regard to the federal government and to North Carolina, complex and consequential internal politics, and lawsuits for the land that Will Thomas had bought for them but was in jeopardy because of his business and personal debts after the war ended. Their story follows that of the formerly enslaved people and white mountain families.

In 1871, Swain County was formed from parts of the existing Jackson and Haywood Counties, and the valley was assigned to this new county whose county seat became Charleston, today’s Bryson City. Jackson Beck, the son of John and Jane Beck, told a telling riddle of the changing county lines in the nineteenth century. Though born in Haywood County in 1821 on a farm about a mile below today’s Smokemont at the mouth of Beck’s Branch, he was reared in Jackson County and lived the last decades of his life in Swain County—not because he had moved but because Oconaluftee Valley was shifted from one county to another twice during his lifetime as the number of North Carolina counties, along with its population, increased.10 The new Swain County soon established public schools supported by property taxes at the rate of twenty-five cents per one-hundred-dollar value.

AFRICAN AMERICANS IN THE VALLEY AFTER THE CIVIL WAR

The 1860 census shows that just a couple of households using the Oconalufty Township post office had slaves. These households were in the vicinity of today’s Mingus Mill and the Oconaluftee Visitor Center. The John and Polly Mingus family enslaved two people, an eighteen-year-old male and a ten-year-old female. The Wesley M. and Malinda Enloe family enslaved seven people, ranging in age from five to fifty-five years of age, with five being male and two female. Other families in Qualla, Webster, and the rest of Jackson County (but not within Oconalufty Township) owned more slaves. In Qualla, these families were the Gibbs, Hyatt, and W. W. Enloe families. In Webster, they were the Sherrill and Coleman families. About forty-six households owned slaves in all of Jackson County. Most notably, William Holland Thomas, who lived in Whittier, owned thirty-eight, and James B. Love, a prominent land owner and a business associate and future brother-in-law of Thomas’s, owned forty-nine. A total of 268 people were enslaved in Jackson County in 1860.11

After emancipation, it is difficult to trace the lives of those who had been enslaved, and the information that can be located through public sources does not provide a satisfying account of their lives. Following individuals across subsequent census records, from the slave schedule of 1860, where they are not listed by name, to the 1870, 1880, and 1900 censuses, where everyone is listed by name, is challenging. In most cases, definite connections cannot be made. For example, the seven individuals enslaved on Wesley Enloe’s farm in 1860 do not appear to be present in 1870. At that time two Black people “work[ed] on the farm,” Nancy Hyatt, a thirty-five-year-old Black woman, and Chrisenberry, also known as Berry, a fourteen-year-old boy. According to a statement by Berry that his daughter Dora Elvira Howell submitted to The Heritage of Swain County, North Carolina, Berry was taken to the Enloe farm by his mother and given to Wesley Enloe, but it is not clear if Nancy Hyatt was his mother. Family accounts establish that Berry had been born on Ute Hyatt’s farm in Marble, North Carolina, in 1855. The ages of Berry and Nancy do not match those of the people listed on the 1860 slave schedule as enslaved by Wesley Enloe. It is not known where the seven went. Perhaps they left the state; perhaps they moved elsewhere in Jackson County or even in North Carolina. But without names, finding a family or an individual by means of only ages and gender is impossible, especially given the changes in households, names, changes in relationships that may occur over a decade, the possibility of mistakes in the census records themselves, and the variability of how individuals’ names were recorded. However, occasionally the lives of those who had been enslaved can be traced. The 1880 census lists a Black household immediately after Wesley and Malinda’s that is surely that of Chrisenberry “Berry,” or C. H. Howell. Later records reveal his full name to be Chrisenberry Napoleon Haynes Howell. Berry was then living with his wife, Sarah, and five other people, most probably in a cabin on the Enloes’ property and working for them; no further record of Nancy Hyatt can be found. Berry and Sarah stayed in the area all their lives and prospered, according to property records and Elvira Howell’s article.12 Even so, among the fifteen Black people who were enslaved by or worked for the Enloes between 1860 and 1880, only two can be reliably identified in later years.

Similarly, neither of the two people on the Mingus farm in 1860 seems to be there in 1870, though a Black male, David Mingus, age thirty-five, was present. Further, the 1880 census lists a separate Mingus household headed by Dancie Mingus, Black and age thirty-one, and Sarah Mingus, white and age twenty-eight, which included five “mulatto” children.13 None of these people can be identified in the 1900 census at all, alas. Unless the records are mistaken, it seems unlikely that David and Dancie were the same person, given the younger age of Dancie in 1880. Sarah’s identity remains a mystery as well. It seems quite possible that some of the members of this family are buried in the small “slave” cemetery located near Mingus Mill. The graves there are unmarked but identifiable as at least eight in number. Perhaps surviving family members moved away once the ownership of the Mingus farm passed to the Floyd family in the 1890s. Making family ties clear is challenged further by the lack of census records for 1890.14

One Black Mingus family member whose story can be told is Charles Mingus. The 1880 census shows that Clarinda, twenty-three, a white granddaughter of Dr. John Mingus, lived in the household along with her son Charles, age five. Clarinda was the daughter of Abram Mingus; he is listed on her death certificate as her father, but a mother’s name is not included.15 Her son Charles is listed as white in the census, but he is probably the son of David Mingus, the Black man who had been on the Mingus property in 1870. Because Abram Mingus was the enumerator for the 1880 census, it seems reasonable that he would accurately list his own household, though perhaps he did not want to designate Charles as mulatto.

The young Charles was to have a very different life than seemed likely. He left Swain County and enlisted in the U.S. Army in Knoxville, Tennessee, on December 30, 1897. He had a long career serving in the Twenty-Fourth Infantry, traveling to the Philippines, and achieving the rank of sergeant. In 1914, he received an honorable discharge. While Charles was living in Nogales, Arizona, his first wife, Harriet Philips, gave birth to the youngest of his three children, Charles Jr., in 1922. The son and his two older sisters, Vivian and Grace, were raised in Watts, a city in Los Angeles County, California, and in 1923, Charles Sr. married Mamie Carson. Charles Sr. died in 1951 and is buried in the Los Angeles National Cemetery, but his son, whose musical talent was evident from an early age, had become a renowned double bassist and jazz musician by the middle of the twentieth century.16 The unexpected connections between a remote valley and a jazz legend show the choices Black people made to gain livelihoods and shape their own destinies.

Some connections among people who were enslaved in the Qualla Township and remained after emancipation are also possible. For example, in 1860, E. G. Hyatt enslaved two people, a fifteen-year-old male and a twelve-year-old female. These individuals seem very likely to be (or be related to) Henry and Eliza Hamilton, ages twenty-eight and twenty-six, respectively, listed in the 1870 census. The likelihood of their connection is enhanced because their household is listed between that of E. G. Hyatt, their previous owner, and his brother A. E. Hyatt. But the next census, for 1880, does not include them. Similarly, in the 1900 census, a Black couple, Anthony and Eliza Lowrey, lived in Qualla; Anthony is sixty-five and working as a farm laborer. But Eliza’s age is marked as “unknown,” making it impossible to guess more about her history. It seems likely that she was close in age to Anthony, which would mean that she may have been enslaved.17 Unfortunately, the Lowreys cannot be identified a decade later.

Charles Mingus (Jr.) performing at the Village Gate Nightclub, New York City, 1978.

KEYSTONE PRESS/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO.

Similarly, a Woodfin family headed by Nick (forty and Indian) and Lucy (forty-one and Black), as well as four of their eight children by 1870, may have been connected to the eleven people enslaved by John Gibbs of Qualla. In the 1870 census, they are listed just below the Gibbs household, which had owned slaves; however, Woodfin is the surname of two prominent Buncombe County slaveholding households, so it was equally possible that after emancipation the couple returned to Qualla because of Nick’s Cherokee heritage. By 1880, Tabitha, a daughter, age twenty, was keeping house for a younger sister, two younger brothers, and a baby of her own. By 1897, only Nick, now age seventy, and Thad, one of the brothers in Tabitha’s home in 1880, appear to be in Qualla; both Nick and Thad are on the Indian census rolls for 1894. Thad was the head of a household of five, and Nick lived alone. None of the other members continued to live in Qualla Township.18

The 1880 census lists seven Black and mulatto households in Ocona Lufty Township (as it was listed), Bird Town, and Big Cove, which are all in Swain County. (The rest of the Qualla Boundary was in Jackson County by then and counted separately; further, the other sections were not inside Oconaluftee Valley but in other watersheds.) These were the families of Berry and Sarah Howell, Dancie and Sarah Mingus (both previously mentioned), Robert and Ellen White, Washington and Margaret Gibson, David and Caroline Johnson, Thomas and Margaret Mills, and Landon and Hannah Tompkins; all but the Howells had at least four children.19

The Johnson, Tompkins, and Mills families all farmed. Notably, they bought land together in 1876 and again in 1895. First they purchased over 200 acres along Adams Creek, a tributary of the Oconaluftee River in the Bird Town section of the Qualla Boundary and south of the national park, for $150; later they purchased fifty acres along Galbreath’s Mill Creek, a tributary of the Tuckasegee River. Curiously, the three families and households do not appear on the 1900 census for Oconalufty Township, Qualla, or Swain County. Thomas Mills sold part of the Adams Creek property in 1890 and the Galbreath’s Creek land in 1899.20

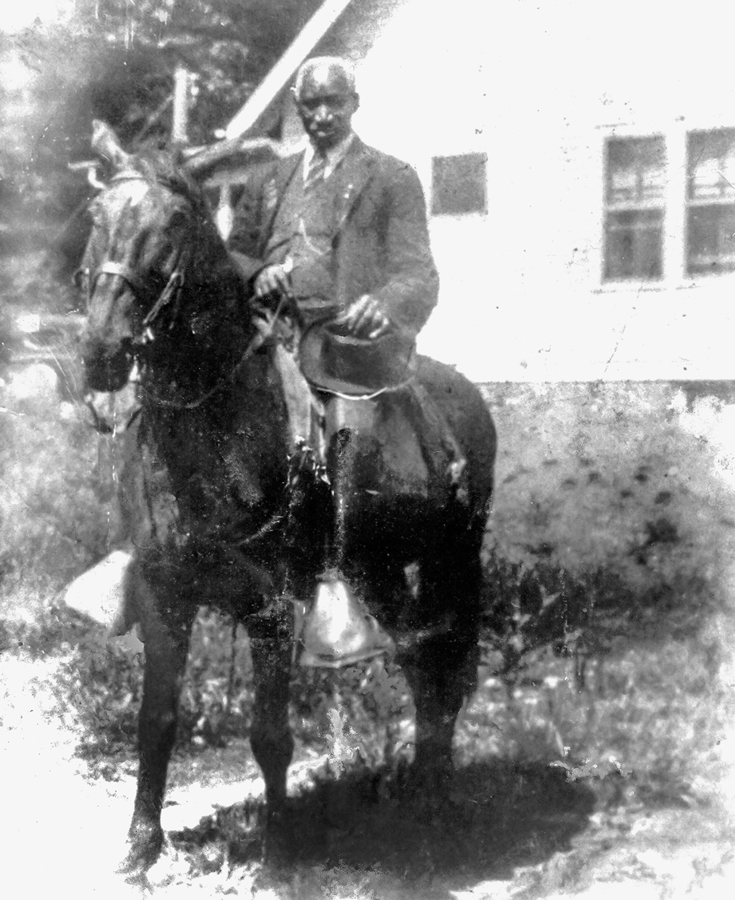

Berry Howell’s biography in the Heritage of Swain County stated that he and Sarah lived and worked on the Enloe farm until he was forty years old, around 1897. He said that he and his wife liked to farm, and he was happy with and well treated by the Enloes. For example, when he had pneumonia, he said that Mrs. Enloe “took as much care for me as if I was white.” (Of course, he may have had multiple reasons for this characterization, but it is the one he made to his daughter years later.) Berry bought a farm in Bird Town and three others during his life; he also worked on others’ farms intermittently as well. He was a deacon of a Baptist church (but not the Lufty Baptist Church, which was white), raised fourteen children with his wife, Sarah (or Sallie) Howell, and also raised seven “orphan children of different folks.” The Howell family appears on the 1900 census as still living and farming in Oconalufty Township as one household. According to property records (which don’t entirely match Berry’s account), the Howells purchased about fifty-three acres along Adams Creek for one hundred dollars in January 1884. Notably, the deed states that C. H. already had a home on this land, which was owned by the couple W. P. and S. E. Hyde. A decade later, in 1894, the Howells bought sixty-five acres along Big Jacks Mill Creek, another tributary of the Oconaluftee River, from A. H. and M. E. Hayes, a husband and wife. In 1904, they purchased a seventy-five-acre farm in Sherrill Gap, west of today’s Bryson City, for $560 and sold it in 1909, next purchasing sixty-five acres, excluding the mineral and mining rights, from J. H. and M. Teague, a husband and wife. The Howells also sold land in 1904 to a Teague, sixty-five acres for $300. By the second decade of the twentieth century, the sons of the family—Landon, Thomas, and John—and their wives, were purchasing land, in some cases subdivided lots from land that an older sibling already owned. These were located in Charleston Township, or the current Bryson City. In 1936, Berry and Sarah sold their daughter Dora Elvira a small plot of land for five dollars and “love and affection.” It is likely she used this half-acre lot for her own home as a single woman. Berry died in 1938 at age eighty-two and Sarah in 1943 at age seventy-eight; they were buried in Watkins Cemetery in Bryson City.21

In addition, in 1900, the Powells, a Black family from Georgia with two households, had come to the Jackson County part of Quallatown. One was headed by Lizzie, a widow, and included seven children; the other was headed by William and included his wife, Sarah, two sons, one stepson, and one stepdaughter, both of whom were Johnsons. Perhaps Sarah Howell was an older daughter of William and Sarah’s, but that cannot be confirmed. Members of the Powell family remained in the area, bought land and homes, and lived in Bryson City. They farmed, married, and were neighbors with other Black families in the area, including the Gibsons. For example, Julius Gibson and Lizzie Powell were married in 1910, but after she died, Julius married again, to Avoline Sallie Parrish. Anna Powell, Lizzie’s daughter, married James Thomas. They lived in Bryson City and raised a family. Their descendants lived in the area throughout the twentieth century. A street in Bryson City is named Powell Street, likely after members of this family.22

A fascinating family story emerges from tracing the lives of Harrison Coleman and his wife, Mourning Emaline Gibson, through public records; it shows that white, Black, and Cherokee households after the Civil War were not always separate. Harrison Coleman was born in 1855 to Betty Coleman, who was enslaved by Mark Coleman of Webster in 1860. In 1875, Harrison married Mourning Gibson, the daughter of Washington and Angaline Gibson of Waynesville, North Carolina. Harrison long claimed that he was half Cherokee, and he applied for admission to the rolls repeatedly on behalf of himself and his children. He claimed his father was Koh-soo-yoh-kee, or John Littlejohn, of Soco Creek, a full Cherokee. He was accepted on the Hester Roll of Eastern Cherokees in 1884 along with the three sons he had at the time. By 1900, Harrison and Mourning had nine children, who were listed as “mulatto” in the 1900 census, and they farmed on the Cherokee land that was assigned to them off Goose Creek Road, which was provided by the Eastern Band. Goose Creek is a tributary of Oconaluftee River in Bird Town, just a bit farther west than Adams Creek, where the Howells lived. Harrison died on January 1, 1923, and his death certificate listed him as Native American. As a widow, Mourning continued to farm. In 1927, Mourning, her oldest son, John Nicodemus Coleman, and her daughter Rhoda R. E. Thomas testified at length to Harrison’s Cherokee ancestry to Fred A. Baker, the examiner of inheritance for the Baker Roll of 1928, which was intended to be the final roll for the Eastern Band and the one that would be used to determine land ownership if the federal policy of allotment of tribal lands were executed. The testimony included details of their lives as a mixed-race family. The family stated that although they lived on the Qualla Boundary and the children attended Cherokee school some of the time and also received some government payments, they did not always feel accepted into the tribe or welcome by authorities. Ultimately, Harrison’s heirs were denied enrollment in the Eastern Band. The 1930 census shows that a daughter, Bertie, two sons, and two granddaughters were living with Mourning at the Goose Creek farm, though by 1940 Mourning had moved and was living with Bertie and her seven children in the Gibsontown neighborhood of Haywood County, outside Waynesville. Mourning lived until age eighty-four and died in February 1941. She is buried at the Gibsontown Cemetery in Haywood County along with many family members, both Colemans and Gibsons.23

Chrisenberry “Berry” Napoleon Haynes Howell on his old horse Nan.

FROM THE COLLECTION OF ANN MILLER WOODFORD.

Despite these instances of ethnically mixed households, for the most part, Oconalufty Township and Quallatown were not deeply integrated. No households of white and Cherokee married couples are listed in the 1880 census. One household, that of Jim and Soky Cheoa, a farmer and a wife, shows a marriage of a Cherokee man and a Black woman; they also appear in the 1870 census as a couple. In 1900, there were a few mixed families, but they were rare. Excluding a couple of homes with lodgers and the Cherokee Boarding School and the households of its staff, where Cherokee pupils lived with white teachers, cooks, and others, only 23 households had married couples of different ethnicities out of a total of 549 families. Of these 23, all were composed of white and Cherokee couples except the home of the Coleman family.24

These observations match those of Russell Thornton in his study of Cherokee populations, though he focused on later decades. He found that the North Carolina Cherokee population changed significantly from 1910 to 1930, “from 66.4 percent full bloods in 1910 to 38.7 percent in 1930. Also, in 1910, the North Carolina Cherokees had a higher proportion of full-bloods than the total American Indian population, but in 1930 they had a lower proportion.”25 In 1900, North Carolina Cherokees of mixed blood were predominantly white and Cherokee (429 individuals, or 92 percent of mixed-blood Cherokee), but there were 38 (8 percent) triracial Cherokees (white-Black-Indian), and 2 (4 percent) Black-Indian Cherokees (presumably allowing some double counting across categories to account for a total larger than 100 percent).26

These accounts reveal that the formerly enslaved people of the valley pursued a range of strategies after the Civil War. The records that are available seem to be about those who were most successful in finding their footing as sharecroppers, independent farmers, and laborers, rather than those who may have drifted away from the valley to seek their futures in advance of the Great Migration of the twentieth century. Additionally, a few Black families moved into the area, but most of these people seem to have been drawn by family ties rather than by economic opportunity. Some of the sons of emancipated slaves did work as loggers and teamsters, but for the most part they took up these jobs because they were already living in the valley rather than coming in response to the need for these laborers.