Chapter 9

THE ESTABLISHED FAMILIES FLOURISH

FARM AND COMMUNITY UPGRADES

▲ ▲ ▲

Try as they might, National Park Service interpreters of the Mountain Farm Museum on the south end of Oconaluftee Visitor Center have a hard time overcoming the nostalgia of the place. When I walk around it on a summer day, it is serenity embodied. Yes, chores, sometimes many of them, would have been part of every day for those who worked this land before the park. Note the many structures: main house, meat house, chicken house, apple house, corn crib, gear shed, woodshed, barn, blacksmith shop, springhouse, garden, and field. They suggest a litany of tasks that the Enloe family, servants, hired hands, and enslaved people would have had to do—all the time. It wasn’t easy.

Even on the busiest days, when the place has tourists in every corner, a deceptive stillness pervades it. For me, this stillness is particularly rich at the barn. It is the only structure that is original to Wesley Enloe’s farm. The barn is a wonder for its monumentality—grand, well made, form matching function. I enjoy the aesthetic of the weathered wood, gray in two distinct tones, the featherlike overhang of shingles at the peak of the roof, and the saddle-notched corners. I love walking through it, looking at the sleds and harnesses. My blood pressure and heart rate lower when I do. I have to check myself and remember that this barn was the scene of intense activity, particularly in the fall when livestock was driven to markets for sale, either in North Carolina or overhill in Tennessee. On their way, drovers would have stayed overnight and their animals would have been put up in the barn. Hay would have been stored in the massive loft all year. Though the barn seems an embodiment of idealized agrarianism, that dream is illusory. It’s like visiting a botanical garden and not seeing all the effort that goes into its daily maintenance after hours by busy teams of workers, as if everything looks picture perfect all the time.

The barn and museum seem apart from our economy and our lives, but most of the pressures were not unlike what people face today: social hierarchies, workplace pressures, desirability of specialized skills, profits and losses, seasons, and deadlines. And perhaps there was little choice, no career advancement, and few regular paychecks. The barn marks economic success, and really it is only as typical as that success was, for a couple of families such as the Enloes.

▲ ▲ ▲

THE COMFORTABLE MINGUS FAMILY

A sign of rebound from the Civil War was a new wood-sided, two-story home that Dr. John Mingus built on his land between the Oconaluftee River and Raven Fork in 1877. The first Mingus home had been a log home closer to the river. The new home’s location along the turnpike would have been a profitable one because livestock drivers could overnight there on the way to market. According to park archives, the new home was the “finest and most pretentious dwelling in the park.”1 This account, likely the prose of park historian H. C. Wilburn, continues with a detailed description:

Certain it is that more decorative carpentry is in evidence here than in any other dwelling in the park. Full boxed eaves, with returns; arched window and door casements; arched entablature over the porch; and a decorative type of balustrade. On the inside artistic mantels and casement trim is of beaded and artistic design. Originally there were four large main rooms: two on the ground floor, and two up stairs, with spacious halls between. Later an “L” extension on the back was added. …

All the framing, timbers, weatherboarding, inside finish and trim material was sawed out on a sash-saw mill located at the mouth of Mingus Creek, some few hundred yards distant. Heavy foundation timbers, corner posts and braces were used; all mortised, tenoned and securely pinned together. An improvised dry-kiln on the site seasoned the plank which was then hand dressed, tongue-and-grooved and beaded for the inside work.2

The home’s deep front porch was framed by four two-story columns, and the second-floor balcony was cased with a decorative balustrade and, eventually, screened. A photograph of the home shows full-size brick chimneys on either side of the main home; a third reportedly existed, perhaps at the end of the L where the kitchen was situated. In addition, a two-story stone springhouse was near the home.

Abraham, often called Abram, helped his father build the home. They were aided by Sion Early as master carpenter and by sometime valley resident Aden Carver, who set the stone foundation and helped the family clear the land and fence it with walnut rails. Carver’s pay was several medical consultations with Dr. John.3 At this time, the Mingus household would have included John and his wife, Polly, who were seventy-eight and seventy years old, respectively, and Abram, who was unmarried and in his early fifties. Abram was also elected as school examiner and served as the census taker. As already mentioned, additional family members Clarinda and her son Charles were present as well and perhaps Lucinda Gaither, who was listed in the 1880 census as doing housework.4

After patriarch Dr. John died in April 1888, the surviving Mingus family remained in the new home. Polly lived another six years, dying in October 1894. The property was passed on to daughter Sarah Angeline Mingus and her husband, Rufus G. Floyd. By the 1900 census, their son John Leonidas “Lon” Floyd, forty-three, is listed as the head of the household and living with his wife, Callie (short for Calgonia), two daughters, two sons, and Abram Mingus, seventy-six, who was listed as a boarder in the home he helped build.5 The house, the barn, and the original cabin, which was subsequently used as a smokehouse, stood until 1955, when the National Park Service tore them down.

The next postwar building project undertaken by the Mingus family remains to this day. In 1886, Dr. John decided to build a new turbine mill for corn and wheat, replacing an earlier overshot waterwheel mill design. Though small family-run mills were common on streams, this mill was to become a community hub. It was located centrally near the Mingus home but on the other side of the river and along Mingus Creek. John deeded ten acres to his son, Abram, and his grandson Lon Floyd for the mill. They supervised its construction, which was led, like that for the house, by Sion Early. In an interview conducted in the 1930s, Early said that he spent three months building the millhouse and was paid $600.6 His initials, STE, are carved above the third-floor window just below the central eve of the mill and remain clearly visible. The W. J. Savage Company of Knoxville, Tennessee, installed the turbine, and it was a 13 1/4-inch vertical standard hydraulic-reaction turbine built by James Leffel and Company of Springfield, Ohio.

Mingus and Floyd also purchased a second turbine of the same size for another mill on Cooper Creek, west of Oconaluftee but owned by Uriah Cooper, Lon Floyd’s father-in-law.7 Mingus Mill ran continuously for the next forty-five years and was operated by hired millers. The building is plain but carefully constructed of yellow poplar lap siding over a substructure of dry-laid fieldstone piers and braced posts over the millrace at the rear.8 The mill’s wood race extends upslope alongside the creek about 200 feet and was made of oak planking and locust posts and crossbars. When the race meets the mill building, the water flows into a twenty-two-foot penstock and then into the turbine, which turns the millstones. This design was a great advance for the mountain families, but it was not technologically new in the 1880s. The design was completely established by the 1820s and widely used by the end of the nineteenth century. In addition to Early, a number of Oconaluftee residents worked on the structure. Once again Aden Carver was on the job, along with Bill Bradley, Nelson Sutton, Mell and Ellis Williams, who were Early’s nephews, and Hall McDade, according to Early.9

For many years, the mill and a nearby store run by the Floyd family became workday gathering places for neighbors as they brought in their corn and wheat for grinding. The miller’s toll was one-eighth of the finished product. Many twentieth-century residents of the valley recalled trips to the mill, usually hauling sacks of corn or wheat on horseback and returning with sacks of meal or flour.10

The Enloes’ Perfectly Situated Farm and Home

For an example of the close nature of the community, one has only to note the connection between millwright Sion Early and the Enloe family. Sion married Sarah Thomas Enloe, a great-niece of Wesley and Malinda Enloe.11 Wesley was the son of patriarch Abraham Enloe, who had built his large farm at the mouth of the valley, which came to be called Floyd Bottoms and now is the location of the Mountain Farm Museum. It is easy to imagine how Sion and Sarah may have met: Could Sarah, whose family lived outside the valley, have been visiting her great-uncle’s home and gone to the mill? Might Sarah and Sion have met at Lufty Baptist Church some Sunday at an after-service picnic? In any case, Sarah had cousins her age at the Enloe farm, and that fact explains why she might have been staying there. Sarah’s cousins were daughters of Wesley Enloe and Malinda Lollace, who had married in 1847. This couple had eleven children, two of whom, Alice Minerva and Mary Malinda, were about the same age as Sarah and living at the farm in 1880.12

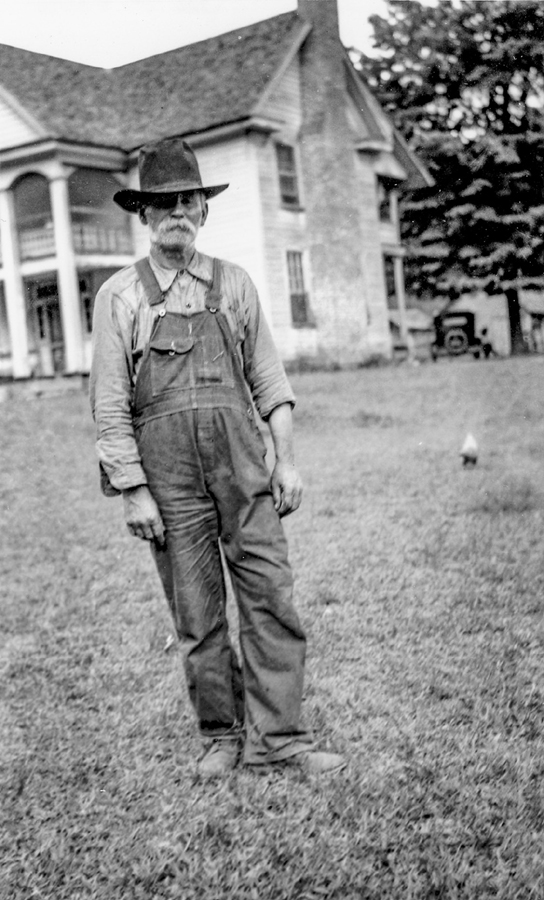

Mingus Mill miller John Jones in front of Mingus home, 1937.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

Because of its choice location, the Enloe place was also a stopover for travelers. In 1888, Eben Alexander, quite likely a Knoxville native who became a professor of Greek at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, set out from Asheville for a hike (or tramp, as it was called then) through the Smokies for “Grand Scenery, Good Fishing, and Plenty of Solitude.” He began in Asheville, passed through the Cherokee village of Yellow Hill, continued up the turnpike and on to Clingmans Dome, Cades Cove, and Chillhowee, where he left the current park land and subsequently visited Montvale Springs, Maryville, and Knoxville, Tennessee. In the early August account of his trip published in the New York Evening Post, Alexander recommended staying a night at Wesley Enloe’s home and another at John McMahan’s, seven miles uphill and “the last house on the road.”13

Berry Howell was employed by the Enloes until the late 1890s and commented on the scale of the operation: “Mr. Enloe always had around three hundred acres of cultivation. Usually he would make around 300 bushels of wheat and always made from twelve to fifteen hundred bushels of corn. We would fatten and kill thirty hogs every year. Mr. Enloe would work ten work hands every day and feed them in crop time.”14

It seems that most of Wesley and Malinda’s children married and moved out of the valley in the final decade of the century. By 1900, Wesley was living only with his daughter Eliza (fifty), who was separated or divorced from her husband, David Manly Hyatt, his granddaughter Pearle (twenty), and his great-granddaughter Meta (four). Wesley’s wife, Malinda, had died December 10, 1897. Wesley lived to be ninety-two and died on August 16, 1903. After his death, the property was sold by the heirs in 1905 to Lon Floyd, Dr. John Mingus’s grandson and the owner of the mill and large Mingus farm.15 At this time the Enloe farm became known as Floyd Bottoms. Despite the gradual departure of Wesley’s immediate family from the valley, other members of the Enloe clan were still in the area. For example, Watson Enloe, a brother of Wesley’s, lived in Tight Run, up Raven Fork, with his wife Mary Elizabeth. Their son Biney married Elmina C. Enloe (known as Clem) in 1872; they stayed on their land until the park forced them out in the early 1930s. Also, Wesley and Malinda’s son Joseph, born in 1865, stayed in Oconaluftee and had a family with Lula Hayes Enloe. Lula was commissioned as postmaster in Oconaluftee in 1912 and held the job until 1915, when Marie Floyd took it over. Joseph and Lula moved to Tennessee by 1920 and are both buried there.16

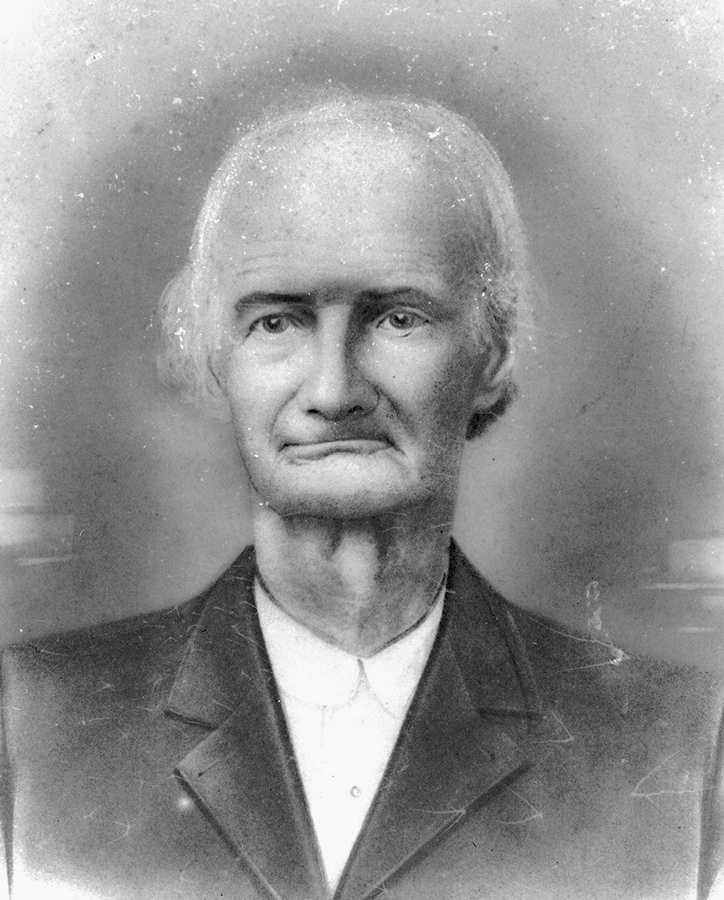

Wesley Enloe.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

Three Curiously Related Conner Families

The Conner name comes up everywhere in the history of the postwar valley, and it is tempting to think of the Conners as descendants of one early Conner couple, as are the Minguses and Enloes. However, the Conner families were not related through Conner ties. In fact, three distinct Conner families inhabited the valley as early as the late 1840s. Most Conners were related, but they were related on the maternal side of their families. Two of the three Conner-family wives were the children of Ephraim and Sophia Mingus, who had homesteaded on Big Cove early in the nineteenth century. (Ephraim was the older brother of Dr. John Mingus, the man who inherited the Mingus farm from parents Jacob and Sarah Mingus.) Two of Ephraim and Sophia’s six daughters, Katherine and Mary Caroline, stayed in the valley and married into two different Conner families. Katherine Mingus married Joel Conner in 1841, and Mary Caroline Mingus married Edward Franklin Conner in the late 1840s.17 The third Conner family was headed by the Reverend W. H. (William Henry) Conner.

Though all these families became intertwined, the Reverend Conner, or William Henry, seems to have been the first to arrive in Oconaluftee. He and his wife, Rachel Gibson, settled in the valley in the early 1840s. The Lufty Baptist Church records show that he was baptized in 1847 by Jacob Mingus. By 1858, he was licensed to preach and served as the supply pastor at a number of Baptist churches in Jackson, Macon, and Swain Counties, including Cherokee churches and Lufty Baptist Church.18 A photograph of W. H. shows a calm face with a high forehead and lower face framed by a full white beard. The line of his mouth is straight, but his light eyes reveal warmth and kindness. In 1876, for $700, he purchased 300 acres from the heirs of Robert Collins, who had died during the Civil War. This purchase included the home and farm along Collins Creek of the deceased Smokies guide. The Reverend Conner and his wife had eight children between 1850 and 1873, but the two who were prominent in the community were “Dock” Franklin Conner, born in 1855, and Wiley Evans Conner, born in 1865. Dock grew to be a successful farmer who raised cattle and drove them to market in Knoxville. He had a large family with Margaret York, whom he married in 1876 at Bradleytown, later known as Smokemont. Wiley followed in his father’s footsteps and became a preacher in 1892 and served a number of western North Carolina Baptist churches until he moved to Knoxville and was pastor of the Fourth Avenue Baptist Church.19

Journalist Vic Weals wrote about Dock’s life and family in the Knoxville Journal in 1976. He explained how Dock’s cattle business operated:

His busiest years as a trader appear to have been when he was middle-aged and past. The farm on the Luftee was a collecting point for the yearlings he bought each spring, most on the North Carolina side in the counties of Haywood, Swain, Jackson and Macon. Each springtime, Dock and the late Good F. Ownby made the rounds of the families they’d been buying from down through the years. These mountain farmers would raise steers to yearlings, one of several head, in anticipation of the Conner-Ownby visit.

Weighing was by guess, but it was said of them that they seldom missed an animal’s weight by more than a very few pounds. They paid the farmer the most recent market price of which they were aware. They bought several head from a farmer on Deep Creek in one instance, and when they got home they learned that the market was significantly higher than the price they had paid him. So they returned to Deep Creek and paid the man the difference. It was a mountain way of doing business that enabled Dock to stay in business.

When they had gathered enough cattle to make it worthwhile, they, meaning members of the Conner family, usually would start a drive back into the mountains, looking for good grazing in the river valleys, on the heads of creeks and on the ridge tops. The pounds that the cattle put on that summer, assuming that the market didn’t go down drastically, represented a profit. Dock almost always sold off all his cattle in the fall. Sometimes he sent them east through Asheville to the market in Richmond, Virginia.

Where the cattle had been grazing when it was time to take them out of the mountains often determined whether they would be driven north and west into Tennessee, or south and east through Carolina.20

Dock’s father, the Reverend W. H. Conner, passed away following an accident on Deep Creek. The story goes that he was crossing Deep Creek in February with a wagon and turned over into the icy water. On many parts of Deep Creek, the banks are steep and challenging for someone with a horse-drawn wagon. It is possible that he was helping his son with the cattle operation in some way at the time. He caught pneumonia afterward and died on March 14, 1887. Lufty Baptist Church held a two-day memorial service honoring his memory. This event shows how central the church was to the white community; it was where aunts, uncles, in-laws, and cousins worshipped together. The service took place eight months later, in November, and began with a baptism in the river of two Mathis children and two Treadway sisters. The memorial service brought a number of former Lufty preachers back to the valley, including the Reverend Richard Evans, who had been W. H.’s friend and colleague throughout the Civil War period, the Reverend J. G. Corn, and the Reverend John Elder, both early prewar Lufty ministers.21 Rachel, W. H.’s wife, had died two years before, in the summer of 1885, of unknown causes. They were buried together in a small cemetery along Oconaluftee River. Their graves lie side by side with a joint headstone shaped by two hearts on either end, inscribed with their names, dates, “Father” and “Mother,” and “Gone from our homes, but not from our hearts.” Two other graves in the cemetery are likely to be those of two children who did not survive into adulthood.

Joel Conner and Katherine Mingus Conner headed another Conner family living along the western side of the Oconaluftee River after the Civil War. They lived on land Joel had partly inherited from his parents, Samuel Conner and Nancy Swearingen Conner, and partly purchased from Joel’s siblings, who had relocated to White Oak Flats (later Gatlinburg, Tennessee) in the late 1840s and early 1850s. This land included property previously owned by both John Hyde and Jacob Couches along Couches Creek, below Tow String Creek. Samuel had purchased this land in 1819 and 1834. Samuel and Nancy had been charter members of Lufty Baptist Church when it was first organized in 1836. But after Samuel died sometime before 1840, his widow and the other nine siblings moved to Tennessee, leaving Joel as the only child still in North Carolina.

Joel and Katherine had a family of nine children as well, who were born between 1843 and 1865. Their homeplace included a mill along the banks of Oconaluftee River. Several of their children married into other valley families as they grew up: Elmina married sons (consecutively) from the Bradley and Hughes families, Elizabeth married Taylor Hughes, Arbizena married a McMahan son, and John Henry married a Nations daughter. In addition, Florence Haseltine, also known as Tiny and Tina, was born in 1855 and married Horace Gass, a Sevierville, Tennessee, man who met the family through Joel’s work as postmaster.22

Joel Conner provides a fine example of how families diversified their income in order to shore up their financial security. Before the Civil War, Joel received a contract from the U.S. Postal Service, along with Daniel Wesley Reagan, a prominent resident of White Oak Flats, to deliver the mail from Sevierville, Tennessee, to Cashiers Valley, North Carolina. The route of over ninety miles wound through the mountains and used the Oconaluftee Turnpike; it connected White Oak Flats, the Cherokee towns, Sylva, Cullowhee, and other North Carolina villages. Despite the route’s many stream crossings, no bridges existed to speed the travel.23 A round trip took about a week to complete on horseback, which is why authors Wilbur Zeigler and Ben S. Grosscup separated the behavior of the mailman from every other person they encountered on the road through the valley:

The mail man, mounted on a cadaverous horse, with leather mailbags upon his saddle, is apt to meet the tourist; but, differing from the general run of the natives, he travels on time and is loath to stop and talk. Not so with the man who, with a bushel of meal over his shoulders, is coming on foot from the nearest “corn-cracker.” At your halt for a few points in regard to your route, he will answer to the best of his ability; and then, if you feel so inclined, he will continue planted in the road and talk for an hour without once thinking of setting down his load.24

Of course, the identity of the busy postal carrier cannot be verified, but it might have been Joel. Or it might have been his son-in-law. At some point Horace Gass of Sevierville took over the Tennessee part of the route from Reagan. Presumably, when Horace brought the mail to Joel Conner’s home, he met Florence Haseltine. They married in 1877. For a time, the newlyweds lived with Horace’s family in Sevierville, but after he purchased land in Ravensford, the couple moved to a home there in 1888.25 Horace eventually took over the whole route from his father- and brother-in-law, James Chambers. The post was officially assigned to him in 1897, and later the site of the “office” was moved to a new location, “Stonery,” on the other side of the river at the Gass home. This Ravensford home had a large front porch and front room to accommodate the post office. Haseltine served as postmistress while her husband made deliveries. In time, their son, William Taylor Gass, was postmaster until the Stonery post office closed in 1919. Horace and Haseltine were deeply involved in the life of the community. They were both members of Lufty Baptist Church, and Horace was elected as clerk, deacon, and representative of the church in congregational conventions. Horace also served as sheriff of Ravensford for a time. Even after Horace died in 1907, Haseltine remained in the park until 1937, and she died in November 1938. Horace is buried in the Chambers Cemetery near the home of Joel and Kate Conner, while Haseltine was buried in the Thomas Memorial Cemetery outside Cherokee, North Carolina.26

Katherine “Kate” Mingus Conner’s younger sister, Mary Caroline, born in 1826, married yet another Conner from an unrelated family: Edward Franklin Conner, who was born in Cleveland County, North Carolina. How or where they met is a mystery. But this branch of the Mingus family did not fare well after the Civil War. Edward Franklin reportedly died in 1864 while returning from service, and his wife, Mary, died in 1867 at age forty-one. They left five or six children ranging in age from four to twenty. The oldest was Margaret Clarinda Conner, and the youngest by far was Edward Clarence Conner, called Edd. Little is known about the lives of the other children, but it seems that they did not stay in the Oconaluftee Valley area long after their mother’s death necessitated the dispersion of the family. However, Edd grew up in and around Oconaluftee and, because of his distinctive personality, is remembered as one of the valley’s storied characters.27 His tale follows in the next chapter.

Tightly Knit Becks and Bradleys

By the 1870s, the families of the early white settlers were in their third and later generations. Like many during the nineteenth century, these rural families often grew very large. Mothers might have had a child every year or so for twenty years. Or mothers might have died in childbirth or shortly after, leaving their husbands to marry again. Widowers would have needed an adult female to raise the young children of the first wife and run the home while the husband farmed and brought in income from a trade or labor. Often, second and third wives were younger than their husbands and so bore a number of children as well, creating large families of half sisters and brothers who lived together in one cabin or in a compound of homes on adjacent tracts of land. Children of these large families also grew up and married young, in their late teens and early twenties; they would also have plenty of children, and when five, or six, or ten children in a family had that many children of their own, then many, many cousins resulted. Further, in a valley dominated by just a few families, the ties between families were multiple and complex. And it was not unheard of for cousins to marry.

The Beck family was one of the oldest of the valley, and it became one of the largest after the Civil War. The patriarch was John Beck, who died at age eighty-four in 1861; his wife, Jane, died at the same age in 1869. They raised nine children on their farm near the mouth of Becks Branch.28 One daughter, Elizabeth Beck (1809–1876), married famed guide Robert Collins and raised eleven children. Samuel Beck also stayed in the valley. He fathered seven children with Cynthia White. Their four sons, William, John, Stephen, and Samuel Carson, served in the Civil War.29

John and Jane’s youngest child, Henry Jackson Beck, born in 1821, grew up to be deeply involved with the activities of Lufty Baptist Church throughout his life. He was ordained as a deacon in 1851 and subsequently served as clerk, moderator, and Sunday school superintendent. He is the preacher who officiated over the marriage of 400 Cherokee couples in a mass ceremony, legitimizing long-term relationships among mature couples and even grandparents at a time when it was desirable for them to follow Christian rituals. He was also a man of distinction in the larger community, holding the position of justice of the peace and superior court clerk. Despite these achievements, perhaps the most remarkable was his role as a father; he fathered twenty-two children with three successive wives.30

The dates from the Henry Beck family genealogy suggest a history of trauma, resilience, and longevity. Henry’s first wife was Jane Morrow Sims, and they married in 1843, when he was twenty-two and she was sixteen. They had nine children during the twenty-six years of their marriage until Jane died, along with her infant, at age forty-two in childbirth.31 At this point, her youngest surviving child was four years old and her oldest was eighteen. Less than four months after Jane’s death, Henry married Mary Elmira Haynes, who was twenty-eight. They had seven children during the eleven years of their marriage. Sadly, Mary also died in childbirth at age thirty-nine in 1880. The newborn child, Rufus Haynes Beck, survived. Mary’s oldest child was not yet ten when she died. Three months later, Henry married Harriett Farmer, twenty-seven, and they had five children. The youngest child of this marriage, Sarah “Sallie,” was born in 1889 when Henry was sixty-eight years old. Henry died at the age of seventy-eight in July 1900, and Harriett lived until June 1913, dying at age sixty. All told, Henry’s twenty-one surviving children were born over a period of forty-four years.32

An undated but late nineteenth-century Beck family photograph shows Henry and Harriett surrounded by a crowd of more than fifty of their kin. Another indication of the size of the family and the depth of its family ties in the community comes from a look at the two Beck cemeteries. The “Old Beck Cemetery” is relatively small, with twenty-five graves, including that of Jane Morrow Beck, Henry’s first wife, and of Robert and Elizabeth (Beck) Collins. It is located above the confluence of Becks Branch and the Oconaluftee River and is also known as the Huskey Cemetery. The “New Beck Cemetery,” situated below Becks Branch, holds about seventy graves and includes those of Henry Jackson Beck, his third wife, Harriett, and at least two graves of children from his first marriage, Elizabeth C. Conner and Jacob Henry Beck. Even though fifty of the grave markers in this cemetery are not inscribed, the tombstones that are engraved bear the names of many Lufty families: Ayers, Bradley, Conner, Jenkins, Kimsey, Maney, Queen, and Wilson, among others.33

The Bradley family, whose first farm in the valley was placed higher upslope than the Becks’ but on the same east side of the river, also was large and became elaborately interrelated to neighboring families in Oconaluftee after the Civil War. The Bradleys first came to the valley in the early 1840s when the patriarch, Isaac, purchased 250 acres on the east side of what soon came to be known as Bradley Fork. At this time, Isaac’s family was already large because he had children from two marriages, ten with his first wife, Anne Allison, and eight with his second, Sarah Coxley. A number of the children from his union with Anne, however, were already married and settled in Rutherford County, North Carolina, by the time the family moved to Oconaluftee, so only two sons from the first marriage, James Holland and Augustine, then about thirty-nine and twenty-nine years old, respectively, came to the Smokies. All but one of the children from the Isaac’s second marriage to Sarah Coxley eventually came to Oconaluftee. All told, the second generation of Bradley children included six males and two females.34

Son James Holland had already begun the third generation. He arrived with his second wife, Martha Grant, and seven children, three of whom were from his first marriage. These third-generation children ranged in age from two years to their late twenties. Sadly, James Holland died in 1843, the same year that he bought his own farm in the valley. At that point, his widow, Martha Grant Bradley, would have had six children eleven years old or younger. At least two of these children lived in the valley most of their lives and died on farms along Tow String Creek, a tributary of the Oconaluftee that runs between Bradley and Raven Forks.35

As Isaac and second-wife Sarah’s children married in the late 1830s and 1840s, the couple sold parts of their land to their children and their spouses. Son William J., who married Deborah Roberts, bought land adjacent to his parents, as did daughter Martha and her husband James Reagan and daughter Mary and her husband Israel Carver. The youngest son, Thomas, also bought land from his parents after his marriage to Mary Conner. His tract was likely the homestead because the deed required that he support his parents until their deaths in order to own the land outright.36 Isaac died in 1855, but Sarah survived beyond 1860; she does not appear in the 1870 census, so presumably she died in that decade. Consequently, the second-generation Bradleys are the ones on the scene after the Civil War.

At least one of Isaac and Sarah’s children initially moved out of the valley after marriage. This was their son Andrew Jackson; he married Mary Trentham in the late 1840s in Sevier County, Tennessee, and bought land along the Little Pigeon River. Before then, in 1839, Andrew served in Company F of the third Indian Removal Regiment of the North Carolina Militia, which was tasked with rounding up Cherokees before removal. At this time he likely met his future brother-in-law, Israel Carver, who served at the same time in Company E. Israel must have met his future wife, Mary Bradley, Andrew’s younger sister, this year because she and Israel married in 1839, a couple of years before the biggest group of the Bradley family moved to Oconaluftee.37 So even before the postwar era, the Bradley family was large and spread over the ridge of the mountains in both Tennessee and North Carolina.

A number of Isaac and Sarah’s grandsons served in the Civil War. By the time it was over, at least two, Benjamin Carver (Israel and Mary’s son) and Osborn Bradley (James Holland and Martha Grant’s son) had died. Other Civil War veterans, such as Andrew Jackson Bradley, James Holland Bradley Jr., and Thomas, came home to Oconaluftee. The family story goes that Andrew Jackson Bradley and his family were run off of the farm in Sevier County, Tennessee, during the war because of their Confederate sympathies. Ultimately, the land was turned over to the Trenthams, in-laws, who mostly stayed in Tennessee. At some point, Andrew Jackson, his wife, Mary Elvira, and their children came to Oconaluftee Valley, but it is not clear where Mary Elvira and the nine children she had by 1862 spent the war years, likely with family. Andrew Jackson served in the Thomas Legion of the Confederacy. After the war, in appreciation for his confederate service, Andrew Jackson “received a grant of 100 acres” from his Confederate commander, Col. William Holland Thomas. This land was on Tow String Creek. Eventually, other Bradley households occupied the Tow String area, including Andrew Jackson’s older sister Keziah and her husband William Griffith. They had married in the mid-1830s and moved around from North Carolina, to Georgia, to Tennessee, and back, finally, to Tow String.38

By 1870, the Bradleys were a large, widespread family in the valley. The 1870 census lists eight separate households with the Bradley last name, including fifty individuals. The number increases to eighty-one if the in-law families of the Griffiths, Reagans, and Carvers are counted.39 The relationships become quite complex through intermarriage of first and second cousins. For example, three of Keziah Bradley Griffith’s daughters married cousins. Melissa Griffith married first cousin Zadock Bradley, Rebecca Griffith married half first cousin Morris Bradley, and Armintha Griffith married half second cousin William B. Bradley. Also, Andrew Jackson Bradley’s son Andrew Jackson Bradley Jr. married Zilla Bradley, a first cousin. Another kind of complexity occurred when Sarah Caroline Bradley Reagan, a daughter of James Holland and Martha Grant Bradley, died in 1886 and her widower Richard Reason Reagan married her younger sister Martha Luesy Bradley Bohannon, who had been widowed by her own first husband six years before.40 It seems fair to think that by the end of the nineteenth century, even if someone’s last name was not Bradley, if the individual lived in Oconaluftee Valley, then that person was probably related to a Bradley somehow.

It would be easy to conceive of the typical household of the valley as that of a yeoman farmer, a wife, and their children with a focus on a self-contained homestead. Such families did exist, but they are not easy to research, and they did not have much of an influence on the community as a whole. The idealized small family farm concept does not account for the extended family landholdings and interrelationships between longstanding family groups such as those described in this chapter. These large, long-term families functioned like family enterprises with operations well beyond subsistence. They were resourceful and largely able to sustain themselves from their own harvests, but they raised and sold surplus crops and livestock outside of the valley. They ran grain and lumber mills, carried the mail, and preached at a church within the community. Their economic lives were multifaceted and expansive, rather than narrow and insular. This outlook may be why, at the end of the century, they were open to large-scale logging rather than opposed to the environmental ravages that it would bring.