Chapter 11

QUALLA’S LONG STRUGGLE FOR SECURITY

THE EASTERN BAND IS ESTABLISHED

▲ ▲ ▲

Early summer is the perfect season to drive on the Blue Ridge Parkway. The air is clean and life seems easy. Heading north from Newfound Gap Road, the first overlook is Oconaluftee River Overlook. I cannot see either the river or Raven Fork, which is the closer stream, directly from the pull-off. The forest has rebounded since the name was attached; it must have once been visible, and in a different season some of it may be. I crossed the river a ways back when I entered the parkway.

At the overlook, a hazy mid-distance green vista of the valley and mountains stretches just beyond the ferns and rhododendrons at the edge of a bluff. Ahead is Mount Stand Watie at 3,961 feet elevation, with Newton Bald just behind it, even higher, at 5,000 feet. To the left, with two antennae at 4,600 feet, is Mount Noble, which lies on the park boundary. To the right, Mount Clark rises to 3,854 feet. Along with the overlook’s, these names have a curious sort of significance and reflect the decision making of the park’s 1930s–40s nomenclature committees. First of all, the “bald” is not really a natural bald at all; its peak has regrown. It was named after a Newton family who lived in its vicinity, somewhat west of the valley. The two mountains in the center and to the right are named after prominent Cherokees, but not members of the Eastern Band. Stand Watie was one of the small number of Cherokees who signed the Treaty of New Echota, which doomed the nation to the Trail of Tears. During the Civil War, he was principal chief of the Cherokee Nation out west and was promoted to the rank of brigadier general in the Confederacy for his fierce leadership of Cherokee troops in Arkansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma. He was the only Native American to reach the rank of general in the Confederacy. Mount Clark celebrates the achievements of Watie’s grandson Joseph James Clark. Clark, also a member of the Cherokee Nation, served with distinction in World War II as an aviator for the U.S. Navy, rising to the rank of admiral. Then he commanded the Seventh Fleet during the Korean War and was highly decorated for many achievements. Yes, Watie and Clark were prominent Cherokees, but they were hardly hometown heroes of the Eastern Band. Even so, these infelicities do not mar the glorious view.

Furthermore, they make the reality of the Cherokee Central School complex—mostly obstructed from view by vegetation and just a short distance below—even more poignant. It sits on the land known as the Ravensford Tract, which was the site of the logging town of the same name. In the 1910s and 1920s, a large two-story school stood on this site to educate the children of the loggers. After decades of requests and negotiations, the land was traded back to the Eastern Band from the National Park Service in late 2003 for a larger tract going to the park along the parkway. It exemplifies the success of the Eastern Band’s long game to remain on ancestral land and secure the community with a stable and prosperous future.

▲ ▲ ▲

AFTER THE CIVIL WAR ENDED, the Lufty Cherokees in North Carolina were surviving—but in distressed conditions. They had endured the same dangers and privations as the white families during the war, but their hunger and impoverishment were significantly more severe, no doubt because the war entirely disrupted their agriculture and their involvement in the market economy of western North Carolina. They simply had less in the beginning and much less at the end of the war. Another destabilizing factor was that William Holland Thomas—their longtime advocate, former Confederate commander, principal adviser, and liaison to county, state, and federal officials—was no longer capable of protecting their interests. In the last year of the war, he began to experience episodes of mental instability, and after the end, it became clear to his family, business associates, government officials, and Cherokee leaders that he would not be able to continue in the strategic role that he had once played. This change led to years of legal disputes about the land that the Cherokees inhabited in Quallatown, which was mostly adjacent to the white Oconalufty Township community, although some Cherokee land holdings were intermingled with white tracts and some remained in the Snowbird area, about forty miles west. Thomas’s decline also ushered in an era of factionalism and contested eastern Cherokee leadership. Consequently, the Reconstruction period for the Lufty Cherokees was marked by multiple social, financial, and legal challenges. They faced these challenges with the benefit of assistance from government agents, lawyers, and white teachers and missionaries, as well as with their own growing numbers of educated and capable leaders, but the motivations and agendas of the outside individuals and groups were never as transparent, long-lived, or clearly benevolent as Thomas’s had been. Unfortunately, on occasion, even Cherokee leaders’ incentives were self-serving. During this period the Lufty Cherokees traced a precarious arc from a vulnerable remnant of the Cherokee Nation to an established and nationally recognized tribe, the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indian.

An immediate crisis at war’s end was a smallpox epidemic among the Lufty Cherokees. The disease was brought back to Qualla by a returning Cherokee soldier who had fought for the Union and had been located at an infected camp near Knoxville. Though he died shortly after his arrival home, the telltale pustules were not immediately noticed and many in the community attended his funeral. A week later, Thomas recognized the disease on mourners. In November 1865, he asked Dr. John Mingus for an ounce of asafetida, which is a mixture of castor oil, garlic, and camphor worn about the neck, and “at least two gallons purified whiskey” to share as preventatives. When the disease spread, Thomas brought in a doctor from Sevier County, Tennessee, but his vaccine failed and many Cherokees also distrusted him and his instructions for care. They resorted to cold river plunges to treat the fever. This traditional remedy resulted in death; about 125 smallpox victims passed away, a significant proportion of the population. The episode set a somber tone for the remainder of the decade.1

The year 1866 included other significant events. On February 19, the general assembly of North Carolina granted the Cherokees permanent residency in the counties where they now lived. But it did not grant them standing as citizens of the state. This act secured the Cherokee payment of federal money from before the war; however, the state proposed to the federal government that only the interest on the funds be paid. George W. Bushyhead, a Cherokee headman in Macon County who had risen to prominence, was granted state funds to take the request for payment to Washington, D.C., which he did in March. Amid a number of complicating factors—federal recriminations for the Lufty Cherokees’ support for the Confederacy, postwar upheaval, and internal division over whether the eastern Cherokees should migrate west and join the Cherokee Nation—the payment issue remained unresolved. Bushyhead contended that 800 Cherokees wanted to go west, though few who lived in Qualla were interested. For more than two years, no funds were released to alleviate the suffering of the Lufty Cherokees.2

In early March 1866, another recovery effort got underway. Will Thomas and Abraham Mingus signed an agreement to build a mill that could grind both corn and wheat on land owned by Thomas inside Qualla. Mingus would oversee the mill’s construction, including the acquisition of a set of burrstones, but the two would share expenses and proceeds. It is interesting to note that this mill project preceded the construction of the turbine mill on Mingus Creek by two decades. However, whether this mill in Qualla was actually built remains uncertain because it does not appear on a map dated 1876, though three other mills are indicated, one in Big Cove at the farm of Chitolski (Falling Blossom) and two others on Soco Creek. No doubt other small mills dotted the area to serve farms in other parts of the community. Thomas’s Qualla tannery also continued after the Civil War. The original store remained open, too, but was signed over to James Terrell, Thomas’s longtime business partner, in 1874.3

Even as some glimmers of progress emerged, fate created additional problems for the Cherokees. Though Thomas was actively trying to reestablish his businesses in order to bring in funds to pay debts, he was soon impaired by violent mental breakdowns and failing physical health. In March 1867, he was declared insane and committed to the state asylum, Dix Hill in Raleigh. The cause was likely late-stage syphilis, diagnosed some years later and acknowledged as the cause of his death in 1893. After a month’s stay in the hospital, he returned home for a time. Years of intermittent lucidity and insanity followed; at turns he threatened family members and worked selflessly to buoy up the Lufty Cherokees. But he entered a period of decline with multiple hospital stays. The Cherokees’ interests were directly affected by this personal tragedy because Thomas’s businesses and financial matters were elaborately intertwined with theirs. For years, serving as their agent, he had bought land for them in his name in order to secure their geographical home. For a variety of reasons, it was easier for Thomas to hold the land in trust for the Lufty Cherokees and to pay tax on it for them. He extended them loans to pay taxes, sold items on account in his stores, and supported them in innumerable ways. As his health failed just when his debts became overwhelming, the Lufty Cherokees’ tenure on their own land was jeopardized because the deeds were largely in Thomas’s name. Much of Thomas’s land was auctioned off to cover his debts, and the Cherokee land was included. William Johnston of Asheville purchased the Cherokee land for a fraction of its value at this time, but he agreed to sell it back for $30,000. In the face of this predicament, Thomas resigned as agent (or “chief” according to some sources) in 1867.4

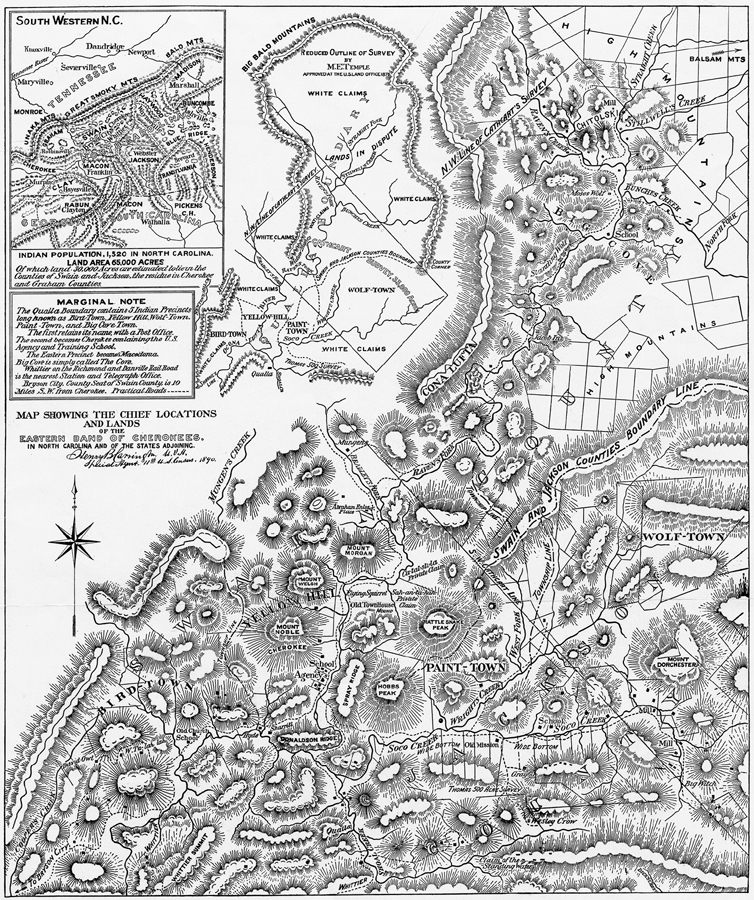

Henry B. Carrington, Map Showing the Chief Locations and Lands of the Eastern Band of Cherokees, 1890.

WILSON SPECIAL COLLECTIONS LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL.

A year later, Congress responded to the payment requests pressed by Bushyhead. It formally recognized North Carolina Cherokees as a distinct tribe, like other tribes, and placed the tribe under the supervision of the U.S. Department of the Interior. It also authorized payment of interest to tribe members on the funds granted after the Trail of Tears. Finally, in 1869, some of the North Carolina Cherokees received about twenty-four dollars per person. Unfortunately, these payments were reduced from what they should have been because of graft by Silas H. Swetland and James G. Blunt, Washington, D.C., attorneys who distributed the money and acted as power of attorney. Through an illegal and brazen scheme, they double-charged for their commission and left $6,000 in claims entirely unpaid. As he paid out claims based on a revision of the Mullay Roll of Cherokees of 1848, Swetland counted 730 Cherokees in Qualla and 912 in Graham, Macon, and Cherokee Counties.5

A DECADE OF DRAMATIC CHANGE

Amid intense internal factionalism among the North Carolina Cherokees, Salonita, a fullblood Cherokee, was the first principal chief elected under the Cherokee constitution in late 1870. Also in 1870, the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians (EBCI) was authorized by Congress as an official tribe to bring suit in federal court against agents who had defrauded them, including Thomas. So even though the Eastern Cherokees held Thomas in high regard personally, they were compelled to file suit against him in order to separate their finances from his and to establish clear title to their land. In the same action, they sued Thomas’s business partner, James Terrell, as well as William Johnston, Thomas’s main creditor and the man who had purchased the land. At the trial for this suit, Thomas supported the Cherokees’ claim to his own detriment. His loyalty was subsequently acknowledged and returned when the EBCI recognized Thomas’s children and grandchildren as members of the tribe. The suit was decided in 1874 after the trial and arbitration. As a result, the Cherokees owed about $7,200 to Thomas for payment for Qualla Boundary land, a sum significantly reduced from the actual debt because of the delay and the suit itself. They were also allowed to purchase land south of Qualla known as the Cheoah Boundary, land that Thomas had lost as well, from both Terrell and Johnston. The cash for all these transactions arrived in March 1875; it was the principal and remaining interest from the government fund created in 1848 after the Trail of Tears. Additionally, the Reverend William C. McCarthy, a Baptist who served honorably as the federal Cherokee agent at this time, paid back taxes to the state. So at last the Qualla Boundary was legally the home of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.6 White squatters still remained on Cherokee land, and laxness in getting all the titles filed in the county office made it possible for whites to continue to homestead and cut timber on Cherokee land for years, no small problems to impoverished Cherokees trying to make ends meet. A U.S. census agent observed that the state had been complicit in the Cherokees’ land problems, criticizing it in a long but pointed nineteenth-century sentence: “The looseness with which, for a small fee, the state of North Carolina permits entries upon lands known to fall within the territory embraced in the deeds by Mr. Thomas adds its uncertainty to aggravate the unrest which is everywhere visible among this people as to what they really own in consideration of the money with which they parted, they rightfully expecting valid and permanent titles.”7

Though the Cherokees were wards of the federal government, they were able to vote as North Carolina citizens at this time. (Such ironies and inconsistencies mark the postwar era.) Most Cherokees were content to keep a low profile in state politics, following decades of advice from Thomas that they “project a positive yet unobtrusive image.”8 But in the years following the Civil War, many white citizens were concerned that the Cherokees could swing an election and usher in Republican officeholders. They presumed that the Cherokees would vote Republican because of the influence of federal agents and other white outsiders. So when Swain County was created from Jackson County in 1871, the line was drawn to split the Qualla Boundary between the two counties, thereby lessening any effect that Cherokees might have on subsequent elections.9

Once the question of the Cherokee land was addressed, issues of education and general welfare again became prominent. During his short but benevolent service as the federal agent, the Reverend McCarthy focused on schools. He established four day schools in Qualla at Yellow Hill, Bird Town, Big Cove, and the Echota Mission, as well as a boarding school to the south in Cheoah. McCarthy observed the children’s poverty and need of clothing, so he requested money to help with these necessities as well as funding for a model farm that would serve as practical education and help prepare students to run their families’ farms. Unfortunately, the secretary of the interior was not persuaded to support McCarthy’s suggestions and dismissed him in 1876.10

During a tour of western North Carolina in 1874, writer Rebecca Harding Davis observed the Cherokees’ keen desire for their children to have access to education. “All that they want of white men is schools,” Davis quoted the preacher Inoli, “an intelligent old man of sixty.”11 The Cherokees she met reported that they could not keep white teachers long because of the remoteness of the area; for them, this was the major obstacle to maintaining the schools from year to year. Davis observed a number of households, ranging from ones that were basic and dirty with despondent adults to others that were neatly kept and adequately but plainly provisioned with owners hard at work in their gardens. She saw the same range in circumstances, education, and outlook among the Cherokees as she did among the white mountain families. Although her standards were those of the dominant white culture, she declared that the Cherokees were capable of more than their present circumstances permitted them to achieve:

They were neither vicious nor vulgar in a single instance. On the contrary, they were grave, thoughtful, self-possessed: the vacancy in the face arose from lack of subject for thought, not of the ability to think. We visited, however, several huts belonging to Indians who could read and write in Cherokee, and even that small degree of education told in clean floors and neat flannel dresses; the iron pot and wooden spoons were still the table furniture, but a little shelf on the wall with half a dozen cups and saucers of white stoneware, kept for show in beautiful glistening condition, hinted at a latent aesthetic taste, just as plainly as would Indian cabinets laden with priceless bric-a-brac elsewhere. Packed away in these huts were always dress-suits of cloth and bright woolen stuff for state occasions, including always a high hat for the men and hoop-skirts for the women.12

Davis also met the Principal Chief Sowenosgeh, who perhaps was Salonita at his farm, and refuted a stereotypical concept of him. “He was neither drunk nor meditating on past glories of his race, according to our usual notions of a chief, but barefooted and clad in patched trousers, hard at work digging, as were his two sons. He was a short, powerfully-built old man, with a keen shrewd eye, which instantly measured his guests and held them at proper distance from himself.”13 The impression of her long article is that the Cherokees needed government aid to recover from the war and to build up essential social services such as schools. But the people, both individually and collectively, were willing and eager for work and advancement.

Davis’s account ends with an appeal to churches to support schools in Qualla and for “some strong and kindly men and women” to recognize her call and come to teach the Indians.14 Despite these pleas for investment in Cherokee education, by 1879, the secretary of the interior allowed the schools to close and instead sent only select students to nearby academies and colleges, using the tribe’s common fund to pay the expense. A couple of years later, the Quakers did respond to Davis’s call for schools and proposed a ten-year plan for them. Barnabus C. Hobbs, representing the Western Yearly Meeting of Indiana, bought thirty-nine acres from Chief Longblanket and reopened day schools in the boundary in 1881. By 1884, Henry Spray became the superintendent; he had previously headed the Quaker school in Maryville, Tennessee. He oversaw the construction of a large boarding school at Yellow Hill with a model farm—as McCarthy had envisioned. Day schools with one or two teachers and about thirty-three students attending each of them were opened in Big Cove, Bird Town, and Soco. Unfortunately, Spray was accused of encouraging the Cherokees to vote Republican in the election of 1884, and this rumor resulted in strong white opposition both to Spray and the schools. Under the subsequent Democratic administration of President Grover Cleveland, federal oversight of the schools was intensified. As a result, the day schools were closed in 1886, though the training school continued into the twentieth century.15

Regardless of the politics that eventually drove the Quakers away from their sponsorship of the Cherokee schools, during their years of oversight, much was accomplished, particularly at the Yellow Hill site, which developed into the Cherokee training school under the administration of Spray, his wife, two additional white teachers, and nine employees, three of whom were Cherokee. Settled on fifty acres of land along the Oconaluftee River, it “winds the bright current of the river.”16 In 1890, it consisted of four frame houses and seven outbuildings, including a barn, and accommodated about eighty-four resident students and twenty-four day students. Despite its success, the training school functioned on a modest budget of $12,000 a year and needed additional funding to house more students and to improve its water system. Instruction focused on “industrial work,” which included “farming, fruit culture, gardening, grazing stock, and some shop work,” as well as housekeeping, sewing, and needlework for the girls. All scholars took “their turn in laundering, cooking, and housework, so that all learn to make bread and qualify themselves for all kitchen duty.”17 The school cultivated about 125 acres of land (presumably most of which was not school property) and brought in “50 bushels of wheat, 500 bushels of corn, 75 bushels of oats, 600 pumpkins, 10 tons of hay, and 50 pounds of butter” in a year. The students also cared for “33 swine and 150 domestic fowls, 5 horses and 56 cattle, including 25 milch cows.”18 They followed a daily schedule that began at 5:00 A.M. and concluded at 8:30 P.M. but made time for recreation and music in the form of a boys’ brass band. A huge mulberry tree formed the bandstand as musicians sat in the tree to perform “Dixie,” “Yankee Doodle,” and “Way Down upon the Suwanee River.”19 The civility and respect of the Society of Friends can be seen in a U.S. census agent’s description of how the school approached religious teaching: “Religious instruction is largely a matter of precept and example, without catechismal or other straight forms for the inculcation of principles of right and duty.”20 This forbearance seems a particularly judicious move, given the strong Baptist and Methodist presence in the area as well as the traditional beliefs of many Cherokees.

CHEROKEE IDENTITY GAINS ATTENTION

By 1880, the Cherokee population had shifted somewhat since the end of the Civil War. The population of Quallatown had increased by almost 100 individuals to 825 since 1869, but that of Macon and Cherokee Counties had declined by more than half to 389.21 This decline was the result of many non-Qualla Cherokees moving west to join the Cherokee Nation and of others moving into the boundary. Though the Cherokees had begun to consolidate as a community in Quallatown and establish it as their tribal center, trespassers still resided on their land. Their continued presence made it difficult for the tribe to pay taxes on the common lands that were occupied by the trespassers. Selling timber out of the Oconaluftee watershed was viewed as the best way to raise the necessary public funds. In addition, lawsuits against settlers and the state for failing to meet the terms of the 1874 arbitration were pursued as remedies.22

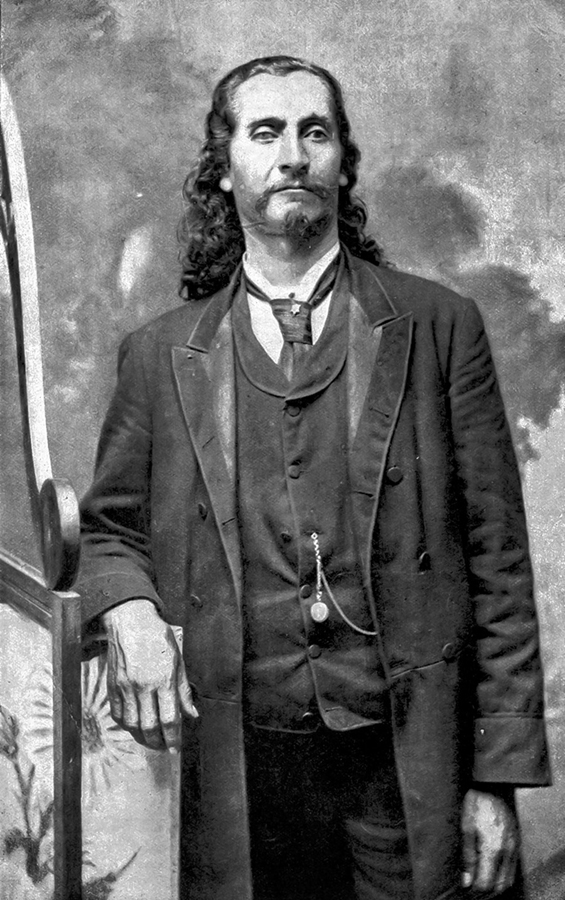

By this point Nimrod Smith (Tsaladihi) had been elected principal chief and established the seat of the Eastern Band in Yellow Hill. Smith was already distinguished in the community. He had served as a sergeant in the Thomas Legion and as a secretary in 1868 of the Cheoah Council, a group that had pushed for federal payments to support the Cherokees after the war. He was a striking figure, one-quarter Cherokee, six foot, four inches tall, and wore a distinctive handlebar moustache.23

On a tour of western North Carolina in the early 1880s, Wilbur Zeigler and Ben Grosscup visited Chief Smith at his “comfortable house of four rooms” near “a frame building used for a school-house, meeting-house, and council-house.” The authors’ description of the encounter suggests that Smith fulfilled all their expectations of an informed and dutiful chief:

We found Chief Smith in his residence, writing at a table covered with books, pamphlets, letters, and manuscripts. The room is neatly papered and comfortably furnished. The chief received us with cordiality. He was dressed in white starched shirt, with collar and cuffs, Prince Albert coat, well-fitting pantaloons, and calf-skin boots shining like ebony. He is more than six feet tall, straight as a plumb line, and rather slender. His features are rough and prominent. His forehead is full but not high, and his thick, black hair, combed to perfect smoothness, hung down behind large protruding ears, almost to the coat collar. He has a deep, full-toned voice, and earnest, impressive manner. His wife is a white woman, and his daughters, bright, intelligent girls, have been well educated. One of them was operating a sewing-machine, another writing for her father.24

Zeigler and Grosscup’s article summarized the structure of the tribe’s government and yearly pay for the chief and assistant chief ($500 and $250, respectively). The elected chief had veto power over a council of three executive advisers and two delegates per every one hundred tribe members, but he could act only with council approval.25 Smith served as principal chief for eleven years, until 1891. Although Smith became discredited in the late 1880s for political corruption, disputes with the tribal council, and personal immorality (for instance, drunkenness, brawling, and adultery), he saw the tribe through a roller coaster of federal and state court rulings.26 These included such critical issues as the legal status of the Eastern Band, the legality of its constitution, the North Carolina citizenship of the Cherokees, and whether individuals or the Eastern Band could use state courts. By the end of the decade, the North Carolina General Assembly recognized the Eastern Band as a corporate body that could sue and be sued in state courts over property matters. The significance of incorporation cannot be overstated, giving the Eastern Band self-governance and determination via its tribal council. Incorporation provided immediate and long-term protection from federal policies that tried to force assimilation and the dissolution of the Qualla Boundary. It also enabled the Eastern Band to develop its own economy through tourism, a market for traditional crafts, and logging contracts.27

Chief Nimrod Jarrett Smith.

COURTESY OF NATIONAL ANTHROPOLOGICAL ARCHIVES, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, INV.01759200.

The 1880s marked the decade when Cherokee culture, rather than just its land, earned new attention from white society as significant and worth preserving. First came wealthy artifact collectors, and after them, the scholarly and sympathetic ethnologist James Mooney arrived. In 1881, the Valentine family of Richmond, Virginia, began to excavate mounds within Qualla Boundary as well as at other sites in Swain County. The family was headed by Mann S. Valentine, who owned a health tonic business, Valentine’s Meat Juice, made from pure beef juice. He was also an avid artifact collector. While the father attended business in Richmond, his sons Benjamin B. and Edward P. Valentine conducted and oversaw the excavations in North Carolina. They continued work for several years.28

The two Qualla mounds were the Sawnooke Mound (called the Sawnooth Mound by the Valentines) and the Bird Town Mound. Mann Valentine wrote a report about the former, describing the size and location of the mound as well as the artifacts and human remains excavated from it.29 Because Cherokees buried their dead in mounds and in the floors of their earthen homes, it was not unusual that grave sites were found within the mounds. As amateurs, the Valentines collected everything they uncovered in the mounds and transported their finds back to Richmond. Many of these items remain today in The Valentine, a museum founded by Mann and his brother, a successful sculptor. For years the museum display included skeletons with their associated objects in glass-covered cases. Today, human remains would not be removed from mounds even by professional archaeologists without the involvement and approval of the EBCI, much less displayed, but the practice among collectors was far less respectful and constrained by regulation in the late nineteenth century. Despite this repulsive aspect of the Valentines’ work in Qualla, the existing accounts of it offer interesting information about the community at that time. For example, Mann’s report provides a narrative description of the Sawnooke Mound, with internal references to attached diagrams:

On the east bank of the Oconee Luftee River, a mile above the village of Yellow Hill, Swain Co. N.C. was found standing alone with no other similar object in proximity, a large artificial structure of earth. The structure was elliptical in form, having its greatest diameter at right angles to the river. It was flat on the top from which the sides sloped downward at an angle of 45 degrees, and then gradually spread itself down, out into the level ground. The greatest vertical section of the mound … was 130 ft, and the least vertical section … 100 ft, is equal to the greatest and least diameter of the base. The greatest diameter of the top … was 56 ft. and the least diameter of top … was 36 ft. height of mound … eleven feet. The original lines of the structure had evidently been changed. Not only by the plough and rains moved the earth from the sides downward, and spread the earth further out, but previously to this the apex had with evident intent, had been cut off and pushed down towards the base. …

The valley of the Oconee Luftee here had been for some time in cultivation—(the mound included) there was no longer any appearance of the old stumps of trees usually left in the clearing. Quite a large number of fragments of primitive pottery were strewed over this estate. In examination of the neighborhood there were found at the bottom of a ridge about 300 yards from the earth structure—what appeared to be two excavations.30

Given what is known about the smallpox epidemic after the Civil War, a local story about this mound has a ring of truth for today’s reader that Mann, arrogantly, decided to discount:

Tradition says that there been an Indian habitation on the top of this structure, that the Ind. Whose house it was having gone east, returned with the small pox from him his family took the disease and they having all died with it were buried in this mound. The inquiry very naturally, therefore, was made of us, if we were looking for smallpox—Having little faith in Ind. Tradition, we do not know that we felt much concern about the small pox story.31

The mound, located about 300 feet from the river, had a number of clay and ash layers with twenty-six graves and artifacts throughout, including beaded necklaces around the necks of skeletons, pottery, carved pipes, bones from deer and bear, bear teeth, deer horn, and shell pins and breastplates, as well as stone and iron hand tools. The mound occupied part of a farm owned by Posey Saunooke, who was about fifty-five years old when the excavation occurred and a member of the tribal council. He seems to have been a son of Chief Stillwell Saunooke. Mann Valentine noted that the current owner was “highly respected and near of intelligence [and] has some white blood in him.”32 Unlike writers Davis and Zeigler and Grosscup, Valentine harbored some prejudice against the Cherokees.

The Valentine sons, not their father, were clearly in charge of the Bird Town Mound excavation, which was located 300 yards from the Oconaluftee River’s north bank on the farm of Jim Keg, a Cherokee, and adjacent to today’s Aquoni Road.33 The sons’ supervisory role can be inferred from several letters sent by the brothers to their father. On July 18, 1883, Edward described the beginning of its excavation:

Dear father We have just started on the Birdtown mound having procured the assistance of 6 Indians. It will make the most complete job of this that we have ever made. The mound is 100 ft. × 93 ft and about 7 ft high. Nothing found yet as we are making a circular trench around it. We are well and getting along as fast as could be expected among such slow people. We took a photograph this morning of the Indians & will take others during the progress of the work. Bob Hyatt will [illegible] carry us through the western counties. We did not get horses as we expected since we were able to get a buggy [illegible] and good [illegible] for 75 cts per day.34

In this mound the brothers found pottery, a clay pipe, and three graves. As word spread that the Valentines were purchasing relics, local artisans made a number of fakes to sell to them. Embarrassment from being taken in by this scheme eventually caused the family to decamp and return to Richmond.35 The artifacts remain in The Valentine Museum today.

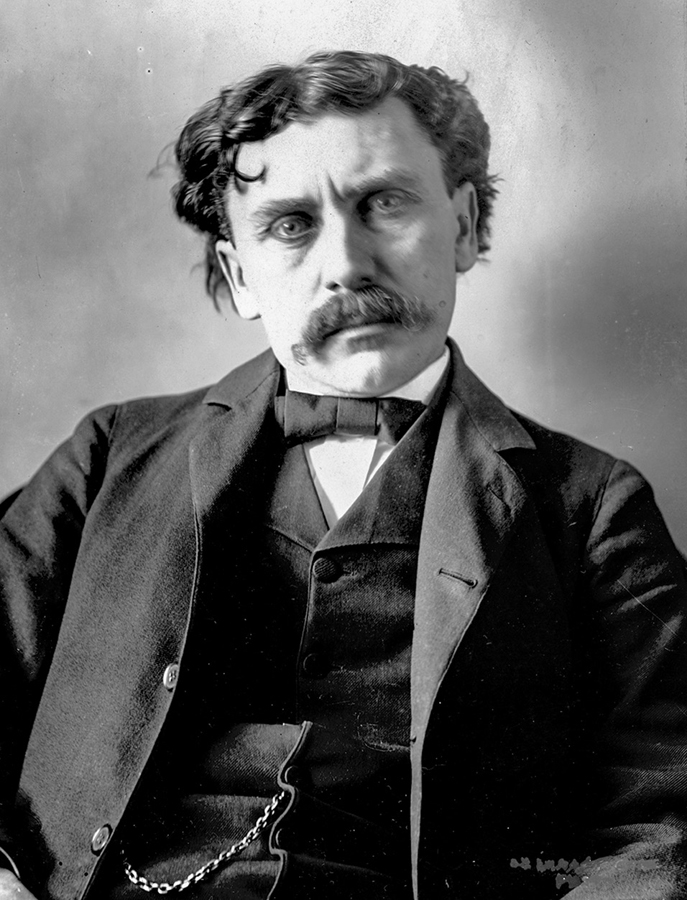

The next individual who arrived to investigate the Cherokees, James Mooney, took a far more serious and sensitive interest in the Eastern Band and created a legacy that has become the foundation of the United States’ understanding of the history and culture of the Cherokees. Mooney had had a childhood interest in Native Americans. Through personal determination as well as considerable independent research, in a key first meeting he impressed John Wesley Powell, the founder of the Bureau of Ethnology, a part of the Smithsonian Institution. At that time Mooney lacked two important criteria for professional anthropologists: gentleman status and formal anthropological education, but the favorable impression he made at his meeting with Powell gave him a path toward acquiring these. In 1885, Mooney, at age twenty-four, joined the bureau as a volunteer and began working on a comprehensive list of tribal names and synonyms to determine how many tribes existed and where they lived. That first summer he was called to sit in on interviews of Native Americans who were visiting Washington. Led by a professional bureau ethnologist, the interviewers inquired about each tribe’s culture. One of these visitors was Chief Nimrod J. Smith, who was in the capital lobbying on behalf of the Eastern Cherokees.36

Mooney’s interest in the Cherokees began with the vocabulary and grammar of their language. When additional meetings with Smith took place the following year, he broadened his focus to mythology and material culture, and by this time Mooney was himself an official staff ethnologist for the bureau. Because Mooney was assigned to work on a linguistic study of Iroquoian languages, of which Cherokee was part, he gained permission from Powell to conduct three summers of field research in North Carolina beginning in 1887. After each season of fieldwork, Mooney returned to the bureau to organize the material he had collected and write about his experiences and about the Eastern Band’s storehouse of traditional knowledge.37

In his first published work about the tribe, Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee, Mooney described how he got to know shamans of the Eastern Band and persuaded them to share their knowledge. He began this process by collecting plants with the help of hired Cherokee assistants. When these people hesitated to explain the incantations that accompanied the use of herbal remedies, Mooney turned to making the acquaintance of elders and tribal shamans who had the authority to decide whether and what they should share with the white government ethnologist via the help of hired Cherokee interpreters. Altogether, Mooney met with at least six shamans, and included almost 600 formulas from them in his book.38 They comprised a cadre of full-blood tribal members who held positions of respect in the tribe. In some cases they were ill or deceased and their pages of cures, charms, and spells were prized by their children as family heirlooms. Ultimately, the descendants and living shamans gave him manuscripts containing medical treatments based on the use of native plants and spoken formulas, as well as a vast array of information about Cherokee beliefs and religion, mythology and history, cultural ceremonies, games, and dances.39

The first shaman to become an informant for Mooney was Ayunini, or Swimmer, a man who had served with Colonel Thomas in the Civil War. Mooney enticed Ayunini to tell him Cherokee stories but could not get him to sing the accompanying songs because Ayunini had paying customers for these. For example, the performance of a song could bring as much as five dollars from an eager hunter who would need this aid to kill bear or deer. Further, Ayunini was reluctant to share because he did not want to risk his reputation among other shamans. But Mooney suggested that Ayunini was wrong to hold back when Mooney was also paying for information, and the ethnologist explained that he could easily seek the same information from others. Mooney also reassured Ayunini that his goal was only to preserve the songs and the knowledge of the Cherokees once the old shamans had died. These appeals to the shaman’s “professional pride” were effective.40 A few days later, Ayunini brought Mooney

a small day-book of about 240 pages … about half-filled with writing in Cherokee characters. Here were prayers, songs, and prescriptions for the cure of all kinds of diseases—for chills, rheumatism, frostbites, wounds, bad dreams, and witchery; love charms, to gain the affections of a woman or to cause her to hate a detested rival; fishing charms, hunting charms—including the songs without which none could ever know how to kill any game; prayers to make the corn grow, to frighten away storms, and to drive off witches; prayers for long life, for safety among strangers, for acquiring influence in council and success in the ball play. There were prayers to the Long Man, the Ancient White, the Great Whirlwind, the Yellow Rattlesnake, and to a hundred other gods of the Cherokee pantheon. It was in fact an Indian ritual and pharmacopoeia.41

Certainly, by today’s standards, Mooney’s coercive tactics seem unethical, though no doubt many are grateful that he succeeded in preserving and publishing these key documents of Cherokee culture. Mooney also persuaded the heirs of deceased shamans to sell (for extremely modest prices) their fathers’ original documents, often providing the means for copies of the formulas to be made by the heirs or by a Cherokee translator. Such was the case of Gatigwanasti, whose manuscript was held by his son Wilnoti after the father’s death. At first, Wilnoti was reluctant to give the crumbling pages to Mooney because of their sentimental value and because he did not want them ever to fall into the hands of rival shaman Ayunini. After considering the matter for a year, Wilnoti eventually was persuaded to sell the manuscript when Mooney returned in 1888. Mooney offered an explanation to him and others that had then become satisfying enough:

By the time the Indians had had several months to talk over the matter and the idea had gradually dawned upon them that instead of taking their knowledge away from them and locking it up in a box, the intention was to preserve it to the world and pay them for it at the same time. In addition the writer took every opportunity to impress upon them the fact that he was acquainted with the secret knowledge of other tribes and perhaps could give them as much as they gave.42

So in time Mooney won over a number of elders who made much traditional Cherokee lore and culture available to him and, eventually, to the public. The original manuscripts were transported to the bureau and stored there for use by the government and scholars. These informed several publications: Mooney’s Myths of the Cherokee, published in 1900, which included a history of the tribe (James Terrell and Will Thomas were interviewed); The Swimmer Manuscript: Cherokee Sacred Formulas and Medicinal Prescriptions, begun by Mooney and completed by Frans M. Olbrechts and published in 1932; and a record of the council of Wolf Town by Inoli, which was later published by Anna Gritts Kilpatrick and Jack Frederick Kilpatrick and which provided glimpses into the civic traditions of the Cherokees before the Civil War.43

Mooney’s work with the Cherokees also helped to develop community leaders. His two primary assistants, James Blythe and Will West Long (Wili Westi), both became important individuals in the Eastern Band. Blythe became the first federal Cherokee agent who was actually a Cherokee, and Long became a leading scholar on the Cherokees and a learned and generous informant and collaborator for future ethnological studies of the Cherokees authored by Mooney and his subsequent coauthor Olbrechts and by Frank Speck and Leonard Broom for their work on Cherokee Dance and Drama.44

While in North Carolina, Mooney observed the Cherokees’ living conditions and was concerned for their health. He noticed that

the door of the Cherokee log cabin is always open, excepting at night and on the coldest days in winter, while the Indian is seldom in the house during his waking hours unless necessity compels him. As most of their cabins are still built in the old Indian style, without windows, the open door furnishes the only means by which light is admitted to the interior, although when closed the fire on the hearth helps to make amends for the deficiency. On the other hand, no precautions are taken to guard against cold, dampness, or sudden draft. During the greater part of the year whole families sleep outside upon the ground, rolled up in an old blanket. The Cherokee is careless of exposure and utterly indifferent to the simplest rules of hygiene.45

Mooney largely dismissed Cherokee medical practice as an ineffective “empiric development of the fetich idea.”46 But he also noted that much Western medicine was based on “the same idea of correspondences,” such as the notion of the hair of the dog curing its bite. Mooney realized that the Eastern Cherokees were suffering from tuberculosis and trachoma, leading to a high death rate and resulting in population declines. He notified authorities at the Office of Indian Affairs of the alarming conditions. In response, a team was sent to Qualla to instruct Cherokees on strategies of preventive medicine. The Cherokee diet was simple: cornmeal dumplings, bean bread, chestnut bread, hominy, and gruel, as well as fish and meats from local wildlife such as squirrel and turkey. Sweeping dietary restrictions applied to sick or ill individuals because of “connections with the disease spirit.” So someone who had rheumatism would not eat the leg meat of any animal because the disease resides in limbs. Also, lye, salt, and hot foods were always denied to those with an illness.47

During his second season, Mooney brought a camera and took several iconic photographs of the Cherokees of the era, including images of Ayunini and other informants such as Catawba-Killer; John Ax, who described the construction of a mound to Mooney; his wife, Annie Ax; a Cherokee woman named Walini; and Ayâsta, who was Will West Long’s mother. She was knowledgeable about native plants as well as the formulas of her deceased first husband, Gahuni. Mooney’s few photos of the Wolf Town ball players, scenes from the ball play, Cherokee houses, and landscapes also capture the details of Qualla at the end of the century.48 Throughout his time in North Carolina, Mooney purchased Cherokee artifacts and crafts and gathered medicinal plant specimens, which he then took back to the Smithsonian.49 Together these comprise an important visual and material record of key individuals and community life. Through insights shared by Ayunini, Mooney also gained information on the purposes and uses of the earthen Indian mounds both in Qualla and throughout the Southeast. Ayunini explained that the mounds were the sites of town council houses and the locus of the sacred fire for each town. These served as ceremonial sources for all fires throughout villages and also played a role for community events such as ball games and annual ceremonies like the green corn dance.50

No doubt, Mooney’s sincerity and perseverance impressed the Cherokees he met. He learned to speak and read the language, an effort that required considerable time and study. He devoted months to fieldwork and observation of the Cherokees in many social and interpersonal settings. He exhibited an interest in and respect for individuals. And he did the same for cultural traditions that many whites felt should be discouraged, such as the Cherokee ball play, because they preserved beliefs and traditions that were neither white nor Christian. Mooney accorded the Cherokees respect as people living their lives, rather than mere objects of study, and if Mooney did not personally agree with cultural practices, he did not question their relevance and value to the Cherokees, as can be seen in his lengthy preface to the Sacred Formulas, where he framed traditions as a religion with purposes not entirely different from those of Christianity:

The Indian is essentially religious and contemplative, and it might almost be said that every act of his life is regulated and determined by his religious belief. It matters not that some may call this superstition. The difference is only relative. The religion of to-day has developed from the cruder superstitions of yesterday, and Christianity itself is but an outgrowth and enlargement of the beliefs and ceremonies which have been preserved by the Indian in their more ancient form. When we are willing to admit that the Indian has a religion which he holds sacred, even though it be different from our own, we can then admire the consistency of the theory, the particularity of the ceremonial and the beauty of the expression. So far from being a jumble of crudities, there is a wonderful completeness about the whole system which is not surpassed even by the ceremonial religions of the East. It is evident from a study of these formulas that the Cherokee Indian was a polytheist and that the spirit world was to him only a shadowy counterpart of this. All his prayers were for temporal and tangible blessings—for health, for long life, for success in the chase, in fishing, in war and in love, for good corps, for protection and for revenge. He had no Great Spirit, no happy hunting ground, no heaven, no hell, and consequently death had for him no terrors and he awaited the inevitable end with no anxiety as to the future. He was careful not to violate the rights of his tribesman or to do injury to his feelings, but there is nothing to show that he had any idea whatever of what is called morality in the abstract.51

Though his career led him to focus on the Indians of the Great Plains after 1900, Mooney had become, among anthropologists, the leading authority on the Cherokees at the time of his death in 1921.52 His scholarship and that of his protégés provided indispensable sources about the Eastern Band and all Cherokees late in the nineteenth century. Mooney arrived just in time. The living shamans were old and the manuscripts of the deceased ones were at risk of becoming lost. Ayunini died in 1899, but he was the longest-surviving informant. Gatigwanasti, whose manuscripts Mooney described as “the most valuable of the whole,” had already died by Mooney’s first summer, and his papers were acquired through his son.53 The work of a third shaman, Gahuni, came from his widow; the shaman had died thirty years before. Inoli died in 1885, two years before Mooney arrived, and his surviving daughter decided to share her extensive set of documents. Tsiskwa (Bird) was sick during Money’s second season of fieldwork and could only be interviewed indirectly because of the taboo against meeting strangers or allowing them to enter a sick individual’s home.54 It cannot be known what would have become of all these manuscripts and the lore they contained without Mooney; surely some if not all would have survived for the Cherokees, if not for the larger society. But just as surely, Mooney’s first fieldwork project, conducted while he was still in his twenties, was highly consequential. Like the partnership of Yonaguska and Will Thomas, the connections between the Cherokee shamans and Mooney seem serendipitous in retrospect, like chance encounters that preserved a culture.

THE CATHCART TIMBER DEAL BRINGS LOGGING INTO THE VALLEY

In the last decade of the century, the Cherokees of Qualla Boundary, now the Eastern Band, continued to face persistent and deeply intertwined issues about their legal status, their leadership, and their land. Despite previous court rulings, the Cherokees’ autonomy, North Carolina citizenship, and status as wards of the federal government remained in question. Any issue that arose was an occasion to rehash this complex matter. It was not clear who had the authority to make decisions, and when the Cherokees attempted to act autonomously, they were met with federal and state obstacles, obstacles erected from authorities who dealt with them inconsistently and were themselves inconstant in their attention. These governance problems might not have been so critical, except that the Cherokees faced immediate threats to their land, which they had worked for years to consolidate and call their own. They also faced social issues of providing education and preventive health care to their members, but though these issues were significant, they were overshadowed by the land disputes. Altogether, a context of vulnerability existed, and it arrested progress for the EBCI.

After Nimrod Smith failed in his reelection bid, Stillwell Saunooke replaced him as principal chief. The new chief, agent Blythe, and the tribal council decided to take immediate action to respond to land issues, particularly to Cherokee land being sold at auction for nonpayment of taxes. The problem was money. It was aggravated by squatters. Agent Blythe investigated land violations and shockingly reported that fifty-six white families occupied and farmed “6,000 acres, most of it good land,” within the Qualla Boundary.55 Considering that only 20,000 acres of the 65,000 in the boundary were arable or tillable, the squatters occupied about 30 percent of land suitable for farming. Because much of Qualla was communally held and on steep terrain, because squatters still occupied significant plots and logged illegally from them, and because tribal revenue was limited to federal funds that could be used only for education, there was no way to keep up with annual property taxes. What the Cherokees did have was timber, vast acres of desirable mature hardwood. So without consulting the Office of Indian Affairs, the chief and council decided to offer the timber of the Cathcart Tract for sale.

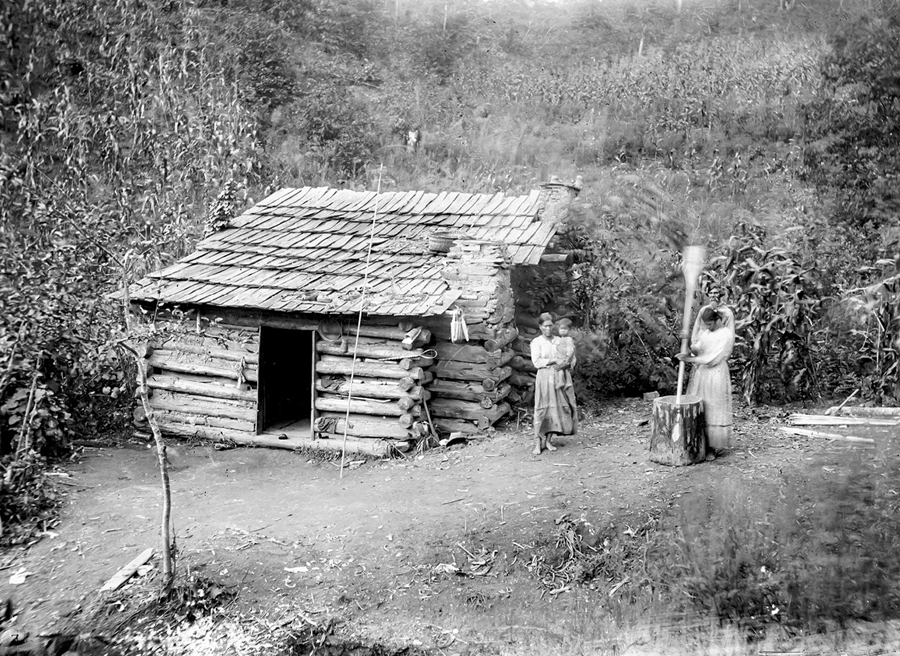

Ayunini (Swimmer) with family members in front of their cabin.

COURTESY OF NATIONAL ANTHROPOLOGICAL ARCHIVES, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, INV.06212100.

The Cathcart Tract comprised 33,000 acres within a rectangular boundary and included the watersheds of Soco Creek and the Oconaluftee River. The name comes from William Cathcart, who had been deeded the land at the end of the eighteenth century. A century later, of course, many individuals, both Cherokee and white, had bought land and settled parts of this tract. Ephraim and Sophia Mingus’s old farm in Big Cove, later that of Clarinda Conner and Aseph Enloe, lay within the Cathcart Tract as well as a good portion of the Qualla Boundary, including Ravensford and Wolf Town. Even so, many acres were not owned by individuals and were also not under cultivation. They remained untouched hardwood forest owned communally by the Cherokees. These were the areas from which the Cherokees sought to sell timber.56 But when the Indian Office said that only enough to pay back taxes could be cut, the deal became the object of federal lawsuits about the Department of Interior’s standing to control the Eastern Band’s actions.

James Mooney.

COURTESY OF NATIONAL ANTHROPOLOGICAL ARCHIVES, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, INV.02862900.

At about the same time, the commissioner of Indian Affairs, Thomas J. Morgan, decided to end its long-standing practice of contracting with religious denominations for the management of Indian schools. The Quakers had done an excellent job of establishing schools in the Qualla Boundary over the last decade, but they dropped out when the scandal with Nimrod Smith arose. Their superintendent, Henry Spray, was dismissed because he was viewed as a troublemaker who might lead the Cherokees astray and, worse, encourage them to vote for Republicans. So Commissioner Morgan appointed a government employee from New York as the superintendent and simultaneously abolished the office of the federal agent to the Cherokees in Qualla. That was the position held by James Blythe, who was a student of Spray’s and an interpreter for Mooney. The new superintendent, Andrew Spencer, was paid an additional stipend to manage all the issues that had previously been the purview of the agent. In one action, then, Morgan fired Spray and his protégé Blythe, who was the first Cherokee to hold the office of federal agent. This was quite a blow to the tribe’s autonomy and leadership. Spencer was the first of three federally appointed superintendents who worked to maintain something close to the quality of the Quakers’ program. They began sending promising older students to out-of-state Indian boarding schools such as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, Hampton Institute in Virginia, and Haskell Institute in Kansas, a strategy that was not successful in terms of completed degrees or apparent benefits to the community.57

When the federally sponsored tribal attorney George Smathers learned of the loss of land from tax arrears along with the proposed timber sale, he intervened for the tribe with the Office of Indian Affairs and managed to gain approval for the sale from President Benjamin Harrison in early 1892. The approval came with conditions that caused trouble down the road. Nonetheless, in preparation for the sale, in the spring of that year, P. W. Mitchell and M. C. Felmet appraised the timber along with the help of several Cherokee axe men to mark the trees. One of these Cherokees was David Blythe, James’s younger brother.58 In addition to the timber appraisal, T. C. Bowen, a civil engineer and surveyor, resurveyed several remote parts of the Qualla Boundary to correct mistakes in the acreage held by the tribe that were presumed to overstate the size and result in higher taxes than were justified. Bowen’s survey led to a new tax assessment of Jackson County land and saved 30 percent for the Cherokees.59

The appraisers’ report provided attractive details on the quantity and quality of desirable trees within the Cathcart Tract. It included estimates for poplar, oak, chestnut, and birch along Soco Creek and its tributaries as well as along the Oconaluftee that totaled more than 10 million feet of timber trees. Along Soco Creek and its tributaries, the appraisers measured a portion of the timber and estimated the rest. They noted that “the above lots of timber are all accessible and easy to handle, and is the finest lot of hard-wood timber that we have ever seen.” Because of time and budget constraints, they provided an “approximated estimate of timber on Ocona Lufty River and its tributaries,” whose 5 million feet of accessible timber was about half poplar, with the balance in chestnut and oak, some maple and ash, and less walnut. The distance Oconaluftee timber would have to travel was a bit farther to the nearest railroad station at Whittier, between eight to seventeen miles away. In addition, two to four times more timber was available from Oconaluftee, but it was “hard of access” and included “hemlock, white pine, different species of oak, and considerable cherry.”60

When the timber was first advertised in June 1892, no bids were made, probably because the president had said that the cutting would have to be limited to what was necessary for the Cherokees to pay back taxes, and that condition dampened the enthusiasm of lumber outfits that wanted to maximize profits. Once the limit was removed, the first bidder was a W. C. Smith from New York City, who contracted to log the timber for $15,000. Perhaps he was merely a speculator who planned to resell the contract. As an army captain who visited the Qualla Boundary in 1893 observed, this offer amounted to less than 50 cents an acre over fifteen years of cutting for timber that he felt was “worth many times the price to be paid.”61 Clearly, the federal government had reason to be concerned about the Cherokees being swindled. Smith abandoned the deal and was replaced by David L. Boyd of Newport, Tennessee, though the contract between him and the Eastern Band had been signed while the Smith contract was still pending. The Boyd contract, signed in 1893, recognized that the Department of Interior would have to authorize it, which could take time. The price and time period were the same as in Smith’s offer.62

During the same years, the tribe continued to resolve the longstanding title disputes and squatter problems. Aided by the legal assistance of Smathers, in early 1894, the Cherokees reached an agreement with “several white tenants and claimants within the boundary.” These people would “vacate” for $24,552, collectively.63 Further, the Cherokees could purchase land held by the descendants of James Love that had long been in dispute. Love had been a prominent citizen of western North Carolina and a business partner and relative by marriage of Will Thomas. He owned 33,000 acres adjacent to the boundary on the northeast side, but confusion about it had existed for years because it had once been mistakenly surveyed as part of the Qualla Boundary. According to the agreement, this land could be purchased for $1.25 per acre. Congress appropriated the necessary funds in August and the agreement went through.64

The Cherokees’ mixed status as North Carolina citizens and wards of the federal government became the heart of the legal battle surrounding the timber sale. Multiple court rulings and appeals ensued, ending in 1897 with a decision by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond, which said that, in fact, the Eastern Cherokees were not North Carolina citizens but a tribe under the supervision of the federal government. An appeal of this decision to the Supreme Court was dropped when the Department of Interior accepted Boyd’s contract. By then, Boyd had sold the contract to Harry M. Dickson and William T. Mason for $25,000. But it was Boyd’s $15,000 plus a little interest that the Eastern Band received. Logging was now allowed to commence legally, though cutting may have already begun unofficially. Following Boyd’s contract, Dickson and Mason had until September 28, 1908, to log the designated parts of the tract, leaving intact any trees on cultivated land or farms. But they continued past this deadline, and the Eastern Band brought suit in November 1908 to stop the logging, claiming that 4 to 5 million feet of lumber at a value of $10,000 had been removed from the tract after the deadline. The issue eventually went to the U.S. circuit court in the western district of North Carolina for a hearing in September 1909. At this hearing, the judge decided that denying Dickson and Mason the right to remove all the lumber they had already cut amounted to a forfeiture of the original contract, and because “forfeitures are not favored by the law,” the defendants had the right to remove fallen timber for “a reasonable amount of time.”65 No additional trees were to be cut. A twenty-first-century reader of the transcript is forced to wonder whether the basis of the decision might have been sheer favoritism for white interests. The judge acknowledged the details of the contract, which the defendants did not observe, but decided in their favor even though the logging period had ended. One consolation to the Cherokees was that by the time this suit was decided, the Eastern Band had already sold land, not just timber, to another company that would log the Straight Fork and Raven Fork areas for the next decade.66

On the plus side, the Cherokees needed the proceeds, modest as they were, from the timber sale, but the Eastern Band’s return to a murky legal status had to be discouraging. With their citizenship under question, their voting privileges were subsequently challenged and then denied in 1900, even though the Eastern Band functioned under a corporate state charter, paid state taxes, and followed state laws. By the way, their voting rights were not restored by federal law until 1930 and not allowed in practice until 1945, when Cherokee veterans returning from World War II forced county registrars to permit actual voting. More ominously, in the first decade of the twentieth century, the federal government began to consider whether the Eastern Band’s land should be allotted, in keeping with the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887, a process underway in the Cherokee Nation and other tribes. But because the Qualla Boundary was owned jointly under a tribal corporation, allotment ultimately did not go forward.67 The prospect of allotment being carried out caused unease and internal division during the roughly forty years that it was national policy. The process necessitated a new EBCI roll to determine who would be eligible to receive land and enjoy such other rights and benefits as voting in Cherokee elections and attending Cherokee schools. Predictably, this roll, known as the Baker Roll, included many more people than previous rolls, and the tribal council challenged it to exclude those whose connections seemed thin.68

In any case, once commercial logging began, the Oconaluftee Valley was forever changed. Roads were improved; access to markets and education improved, too, though slowly. Moreover, the scale of humans’ impact on the land was now apparent, impossible to miss. The Cherokees’ timber sale ushered in a new era of industrialization that would transform homesteads into logging towns and sites, increasing population and heightening the dangers of fire, erosion, land degradation, and logging accidents. It was the beginning of a new era for all of Oconaluftee’s residents.

A few more events marked the last decade of the nineteenth century in Qualla. In 1893, both Will Thomas and Nimrod Smith died, ending their many years of oversight and influence. Three years later, an influenza epidemic—called grippe in those days—struck the Cherokees and resulted in the death of over 150 individuals, nearly 10 percent of the tribe.69 Perhaps they suffered so badly because, as Mooney and traveler Virginia Young both noticed, the Cherokees were prone to consumption and of small stature.70 By the end of the century, more Cherokees could read and write English, though still only a minority, and, paradoxically, the Cherokee ball games had become more common as expressions of traditional culture.

What is most striking, however, about accounts of the Eastern Band written by white travelers, journalists, and government officials toward the end of the century is that they said that the homes, farms, food, and well-being of the Cherokees were very similar to, if not a bit better than, those of their white neighbors. A travelogue written by Young in 1894 noted that Indian “huts” were “nothing different from the homes of poor white people. There was even the usual tangle of sunflowers, zinnias, dahlias and morning glories … [as well as] extensive apple orchards” with sweet, flavorful fruit from overwintering.71 The U.S. census special agent Thomas Donaldson similarly noted that “wages are very low in the mountains of North Carolina, but the cost of living is small, and the Cherokees earn as much and live as well as the white people about them.”72 Also, Cherokee hospitality seems identical to that offered by white mountain families such as the Enloes and the Minguses. When Donaldson visited Chitolski, “a Cherokee of means and influence,” at his farm in Big Cove, the experience mirrors ones recorded about white Oconaluftee farmers:

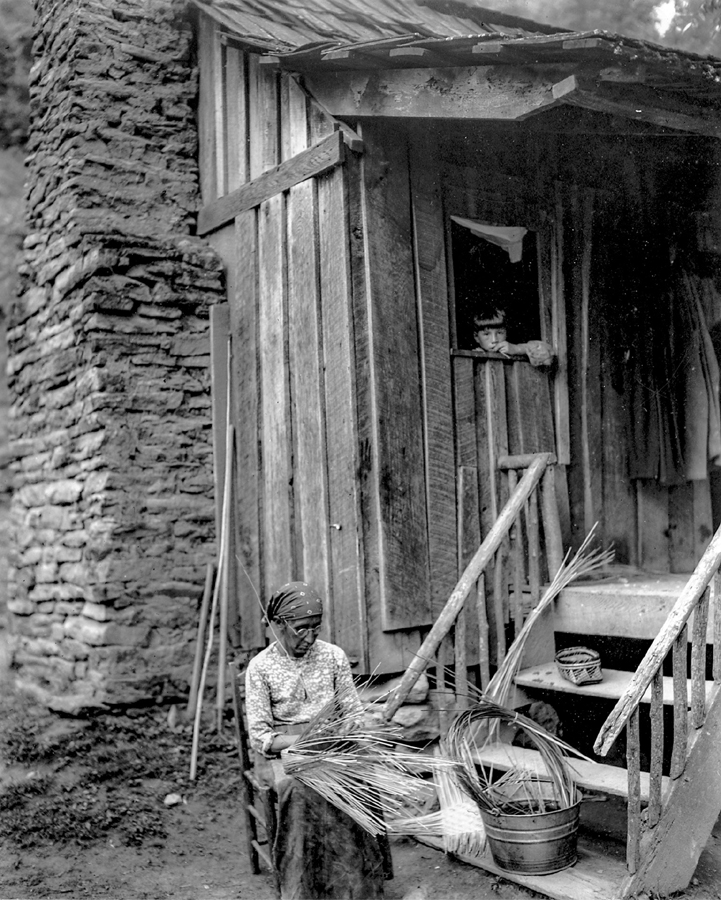

Nancy George Bradley works on a basket in front of her home, 1940. Note the child in the window.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

Cherokee man plowing a field with his oxen, 1936.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

His home is a new and spacious block house, very comfortable, with the usual piazza in front. Upon accepting an invitation to dine, the water was turned upon the wheel of the mill close by, and fresh meal was soon served in the shape of a hot “corndodger.” “Long sweetening” of honey or molasses gave a peculiar sanction to a cup of good coffee, and this, with bacon and greens, supplemented with peaches grown on the farm, made a most excellent meal. … Chitolski’s house is said to be one of the best in the country, and very few houses of the white people upon Indian lands or lands adjacent approach it in comfort.73

Additional cordial visits took place at the farms of Big Witch, a 105-year-old man; councilman Wesley Crow; Vice Principal Chief John Going Welch; and the Reverend John Bird. The agent’s report included detailed descriptions of such public buildings as schools, meetinghouses, and churches (often used interchangeably), as well as fences, farms, and roads. These were evaluated as just as good as and sometimes better than those in neighboring white settlements. Roads and bridges were challenging everywhere:

All roads which border the numerous creeks are subject to rapid overflow in the rainy season or after heavy summer showers, and the streams become impassable. Simple bridges of hewn logs, often of great size, and guarded by hand rails, supply pedestrians the means of communication between the various settlements until the waters subside. In deep cuts, or where the Ocona Lufta river is thus crossed, substantial trestles or supports have been erected on each shore and in the stream, as no single tree would span the distance. Numerous short cuts or foot trails wind among the mountains and over very steep divides. … Wagon trails for hauling timber to single cabins or hamlets are not infrequent.74

Like white residents, most Cherokees were farmers and “domestic and industrious” in their efforts. A few worked as skilled tradesmen as blacksmiths, cobblers, and harness makers, wagon makers, and carpenters. The traditional crafts of basket making and pottery were practiced widely but not yet commercially.75 The human and natural resources for commercial development were in place. With the turn of the century, the Eastern Band would face external challenges, particularly in defending its communal land against allotment. But its tribal council provided a new measure of self-determination that would help it develop ways of sustaining itself economically and defending itself from outside interests. Most of all, the identity of the Lufty Cherokees had been solidified into the Eastern Band.