Chapter 12

FROM BIRDSONG TO TRAIN WHISTLE

THE INDUSTRIAL AGE REACHES THE MOUNTAINS

▲ ▲ ▲

One lazy July evening, the specter of the Industrial Age emerges from the cement bridge at the Smokemont Loop trailhead in Smokemont Campground. Closed to auto traffic, with a gate and multiple road signs, the sixty-foot span shows how close the area was to development. In fact, the area was not close to development; it was developed! Once the site was the middle of a logging town. Today, the bridge is a quaint reminder of that era and a suggestion of the city that Smokemont likely would have become had the national park not been established. This was a bridge built for heavy vehicles, not just the occasional automobile, certainly not for hikers. Swain County invested in its construction expecting many years of use.

Happily, today it is for foot traffic only. I’ve seen it overgrown with saplings, wildflowers, and all manner of plants. Tire wear suggests that it is occasionally used by park service vehicles, but not very often. For the most part it provides a safe crossing over Bradley Fork and leads to a path along a former logging road—an easy after-supper stroll for campers. Second-growth trees abound on the banks and all around. Looking over the parapet midway across, I see wild turkeys poking along the creek side. They are oblivious to me and other humans. On my return, I notice the relief installed in the left-hand abutment by the bridge’s makers: “Designed and built by Luten Bridge Co, Knoxville, Tenn. 1921.” Says a lot.

▲ ▲ ▲

THE TURN OF THE CENTURY brought sweeping changes to Oconaluftee Valley, changes that would transform both the land and the community. The causes of change—logging and railroads—had been approaching for a couple of decades. Locals already understood that the timber on and surrounding their land was valuable. They had used the trees around them for years to build their homes, barns, fences, wagons, plows, and furniture. During their off-seasons, farmers had long practiced selective logging, taking the more valuable large cherry, ash, and black walnut trees and selling them to nearby western North Carolina mills. They could snake out single trees with a team of horses or oxen, cut them at one of the local mills, and then haul them out by wagon on the Oconalufty Turnpike.1

A sawmill had stood at the mouth of Mingus Creek since the 1870s, when the Mingus family constructed it to produce lumber for their new home and grist mill after the Civil War. Another sawmill was in place on Tow String by the 1880s. It was operated by Will Johnson. Bert Crisp, a Mingus Creek farmer and logger, claimed that the mill on Mingus Creek was owned by Thad Watson and was a circular saw. But a more common type of small sawmill was a sash sawmill, which used water power to move a vertical blade held within a frame—kind of like a window sash—through logs. The Tow String mill was a sash mill. In time, these mills brought frame houses and clapboard to the valley, replacing some log homes as siding became the more desirable and upscale building material. Dock Conner’s family built a frame house in 1910 or 1912 on the Collins homestead and tore down the log cabin built by early Smokies guide Robert Collins, for instance. Many of the homes along Mingus Creek and its tributaries were frame houses.2

Residents also removed bark from chestnut oak and hemlock trees, which was called “acidwood,” and sold it to tanneries.3 Will Thomas had run a leather tannery in Qualla since before the Civil War, and by 1911, five large tanneries operated west of the Blue Ridge.4 Forest products had long been a source of income just like ginseng, chestnuts, and animal skins. This low-volume logging had little impact on the wildlife or land, rarely causing fire, erosion, or damage to streams or woods.

SHAPE-SHIFTING LUMBER COMPANIES

Large-scale logging came to the southern Appalachians after companies exhausted the northern forests. It approached Oconaluftee from two directions. The Big Creek area of the Smokies to the north hosted commercial logging operations as early as the 1880s, and the Cherokees introduced outside logging speculators and companies to the watershed with the lease of the timber on the Cathcart Tract in 1893. As already mentioned, the Cathcart Tract encompassed 33,000 acres in the Big Cove, Wolf Town, and Raven Fork parts of the valley as well as adjacent Soco Creek. At least one of the parties of that agreement, David L. Boyd, was from Newport, Tennessee, and likely had also been active in Big Creek. The Cherokees struck agreements with other speculators as well early in the twentieth century. Charles D. Fuller, a manufacturer from Kalamazoo, Michigan, contracted to buy the timber and minerals from a large swath of land above the Cathcart Tract boundary and west to Hughes Ridge, yet still owned by the Cherokees, in 1903. When Fuller did not come through on his part of the deal, a quit claim was executed in 1909.5

As commercial operations got underway, the railroad simultaneously neared the valley. Rail transport was essential to moving cut lumber to markets or mills in the quantities needed to make the enterprise profitable. As early as the mid-1880s, G. V. Litchfield and Company had constructed a lumber mill at Waynesville along the Western North Carolina Railroad line. It contracted with suppliers for more than 4 million board feet of walnut as well as large quantities of cherry and oak.6 The Western North Carolina Railroad had been constructing a line between Asheville and Murphy since right after the end of the Civil War. It reached Dillsboro in 1883 and Bryson City the next year. By 1891, the line between Asheville and Murphy was complete, and soon it merged with other lines to become the Southern Railway Company. Once the railroad neared the Smokies, shorter rail lines owned by logging companies were able to connect with the Southern line and transport felled trees to larger mills outside Oconaluftee Valley.7 In a key U.S. Forest Service Report on the southern Appalachian region in 1902, the authors noted that in the “largest unbroken forest areas” on the Oconaluftee, Cheoah, and Tuckasegee Rivers, “the best timber has been much culled for 20 miles from the Southern Railway, which crosses the middle of the basin.”8 So before the big logging companies even arrived on the scene in Oconaluftee, the most desirable and accessible hardwood had been taken.

As commercial logging ramped up, two main centers of operation in Oconaluftee emerged. One was the logging town of Ravensford, located on bottomland long owned by Wesley Enloe but sold after his death in 1903; this land was east of the Raven Fork tributary of the Oconaluftee River, very near the Cherokee towns of Yellow Hill and Paint Town.9 A succession of companies located here and focused on logging up and along the Raven Fork and Straight Fork tributaries. The other logging hub encompassed the more westerly tributaries of Oconaluftee, such as Bradley Fork, Kephart Prong, Beech Flats Prong, and Collins Creek. These led downslope and downstream to Bradleytown, which became the logging town of Smokemont. Though today Ravensford is part of the Qualla Boundary, home of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, at the time it was a neighboring lumber town, just across the river from Floyd Bottoms, as then the Enloe farm was known, and a couple of miles south of Smokemont. Ravensford was as much a part of the valley during the logging era as Mingus Mill. These two areas were distinct, though the individuals and companies that owned land and operated logging concerns organized into new businesses multiple times over the years. They did business separately and then together amid constantly changing company names and agreements. They opportunistically expanded, contracted, developed subsidiaries, declared bankruptcy, and reorganized into new entities in order to continue seeking a profit from the amazing timber resource of the southern Appalachians. Ultimately, the Ravensford Lumber Company and the Champion Fibre Company remained in business when the land was condemned and bought for the national park. Nonetheless, tracing the chain of company ownership and logging in the valley illustrates how the logging boom and bust from 1900 to the mid-1920s transformed the land and its small, interconnected community.

Along the western tributaries of the Oconaluftee (leading to Smokemont), Three M Lumber Company, a Wisconsin corporation, cut the hardwoods from the Beech Flats area during the early 1900s, and perhaps from Collins Creek a bit later. The Beech Flats logging included 7,000 acres up to 3,500 feet along the riversides, taking hardwoods over 16 inches in diameter. Three M built a tramroad to haul out lumber and had a mill “at the Pole Bridge” across Beech Flats. The lumber was then hauled to Whittier on wagons pulled by mules. Later, the mill was moved down to Smokemont and the logs were run down on tramcars. A tramroad was like a railroad made of lumber; its tramcars ran on interlocking log rails, and these were propelled by a team of horses or, going downhill, sometimes gravity and a brakeman.10 In June 1906, Three M sold its Oconaluftee holdings to William S. Harvey, who was a trustee for the Southern Spruce Company, a New Jersey corporation. Harvey subsequently conveyed the acreage to Southern Spruce, which focused on cutting pulpwood. Pulpwood meant spruce, hemlock, and chestnut—high-acid woods suitable for making paper products. Another company operating in the area was the Harris-Woodbury Lumber Company of West Virginia. It bought and leased land in the upper reaches of the Oconaluftee along Bradley Creek and to the west along Forney and Deep Creeks. It focused on cutting hardwood for saw timber.11

At roughly the same time, the lease on the Cathcart Tract, Cherokee land held by Harry M. Dickson and William T. Mason (who had bought it from David Boyd), was nearing its end. As mentioned, the cutting deadline was September 28, 1908, but the company continued to remove lumber until the end of 1909, when it was eventually forced to stop by a lawsuit brought by the Eastern Band of the Cherokee.12 Attempting to improve the profit that the Cherokees were getting from their key natural resource, the Eastern Band sold the 33,000 acres above the Cathcart Tract that had been previously optioned by Charles Fuller to lumber speculator John C. Arbogast and Associates for $245,000 in 1906. Once again, speculators gained more than the Cherokees because in 1909 Arbogast sold the tract along Raven and Straight Forks to William Whitmer and Sons of Philadelphia for $630,000. Arbogast would continue to work for the new owner as a timber inspector and estimator.13 Part of the deal was that the buyers would build a railway along a route following the Oconaluftee River to connect the Cherokee training school in Cherokee with the Southern Railway at Ela, North Carolina, which was done by 1908. The company became the Appalachian Railway, and it extended the line farther than the school to the logging town of Ravensford by 1912.14

Often, after a logging company or speculator had purchased timber rights or land, cutting was delayed until prices—either for lumber products or for the timber or timber rights—increased.15 By the time sizable operations got underway there in 1918, Whitmer and Sons had deeded the Ravensford land to Parsons Pulp and Lumber Company of West Virginia. After a bankruptcy, this company eventually reorganized in 1923 as Whitmer-Parsons Pulp and Lumber Company. These changing names reveal several key points: the companies often were not profitable, the owners were interested in both pulp and hardwoods, and corporate reorganization allowed the same people to continue business with new investors.16 Four years later, the name changed a final time to Ravensford Lumber Company, which soon ceased operations and was bought out by the state for the national park.

An important expansion of the lumber industry throughout western North Carolina but also in the Oconaluftee Valley came with the establishment in 1905 of Champion Fibre Company in Canton, North Carolina. It was a subsidiary of an established Ohio paper company and was led by Peter G. Thompson and directed by his son-in-law Reuben B. Roberson, who lived in Canton. It bought 300,000 acres in and around Canton and built a pulp mill there, which opened in 1908. Champion Fibre’s business was to cut and buy pulpwood that was not desirable as saw timber but was suitable for paper and cardboard manufacturing. It was an ideal second-wave logging concern once the hardwoods were gone or of limited size. At first, in the Smokies, Champion Fibre did not engage in cutting but purchased pulp wood from other outfits for processing. Toward this end, in 1911, Thompson expanded the company’s operations. Along with major partners William Whitmer and Sons—who were then operating at Ravensford—Thompson formed Champion Logging Company. The company purchased 100,000 more acres and expanded its operations into saw timber logging throughout the northwestern parts of the Smokies in both North Carolina and Tennessee. It also agreed to provide Champion Fibre with a minimum of one hundred cords of pulpwood a day at a fixed price. John Arbogast, the early investor in Whitmer and Sons, was Champion Logging’s general manager.17 To facilitate transport, Champion Fibre financed a further extension of the Appalachian Railroad to the mill at Smokemont in 1912; this extension became the Ocona Lufty Railroad in 1918.18 The joint logging company lasted only until the last quarter of 1916, when it went bankrupt and was sold to Suncrest Lumber Company, whose center of operations was farther north, along the Pigeon River.19

Despite the demise of Champion Lumber Company, Thompson and Roberson’s Champion Fibre Company survived and thrived. Once its subsidiary was out of the picture, and following a detailed timber survey conducted by an outside firm, it bought the holdings of Southern Spruce and Harris-Woodbury along the western Oconaluftee tributaries. Champion Fibre also sold spruce to the military during World War I for use in airplane construction.20 Montvale Lumber Company entered into an agreement with Champion Fibre in 1917 to supply it with the “tannic acid wood from spruce, chestnut, etc.” from a tract above Cherokee on the Oconaluftee River. Montvale would itself manufacture the hardwoods from the land.21 With Champion Fibre in charge at Smokemont and in place as the owners of the highest reaches of the watershed, its operations expanded rapidly in 1917.

In addition to the centers at Ravensford and Smokemont, other companies logged parts of the valley. Most notably, Geissell and Richardson of Philadelphia bought stumpage, access, and operating rights for timber under forty-six inches in diameter along Mingus Creek and its tributaries. This land was owned by John Leonidas Floyd, his wife, Callie, and their children, heirs of the Mingus family who built the original grist mill and were early residents of the valley. The Floyds sold the timber in two contracts specifying several parcels of land; the first agreement was reached in 1915 when John Leonidas Floyd was still alive, and the second occurred in 1917 after his death and lasted for four years. Geissell and Richardson is said to have brought the first steam-powered band mill to the valley, though its exact location is unknown. In its heyday the company employed about eighty men full time.22 Some of the old homesites and the cemetery up Mingus Creek are remnants of the community that emerged along with this operation. About two miles up the creek, a school provided some education to the residents’ children. Farmer and logger Bert Crisp said there were “around 35 or 40” families living up Mingus Creek during this time, including members of the Woody, Jenkins, McLaughlin, Watson, Ownby, Mack, Wilson, Nations, Hyatt, Mathis, Gibson, Beck, Dowdle, Knight, Parson, Everett, and Lambert families.23

LOGGING STEEP SLOPES AND RIVERBANKS

Despite the transience of the logging companies themselves, they cut extensively and had lasting impacts on the land. Unlike the earlier logging done by valley residents and local concerns, these companies penetrated previously inaccessible areas of the forest via switchbacks that reached high up steep slopes. Using the crosscut saw, three-man crews clearcut massive swatches of land. While this technique for felling trees was traditional, the innovative methods used to move cut timber to railroad cars were very destructive and left huge quantities of debris, tore up streams, and created conditions ripe for wildfire. Early on in the commercial period, saw timber was ball-hooted (simply rolled or slid) to a stream whose waters would convey it downstream after heavy rains. At the confluence of streams, crews would erect splash dams. These were vertical boards spread across pools where water and logs could collect; once full enough, the boards would be removed or blasted out, and the resulting torrent would carry logs downstream. With both these methods, logs would be lost upstream when water levels were low or when the current and rocks would throw them onto the stream bank.24

Over time timber removal shifted from tramroads and splash dams to steel rails and steam locomotives. Steel rails could accommodate much heavier loads than tramroads, and in comparison to splash dams, they lost fewer logs. They also allowed for all species to be cut at one time. The tracks followed streams uphill, though on steep slopes either a series of switchbacks or an incline railway was engineered. In coves, V-shaped log slides conveyed cut timber to railcars. Moreover, steam-powered ground and overhead skidders were used to move cut timber to railcars via cables, and a steam-powered log loader—called a Surry (pronounced Sary) Parker—lifted logs onto cars. All of these innovations enabled faster and more complete cutting, and they provided greater access to very steep slopes. For example, overhead steam skidders could reach trees as far as 2,000 feet away from the skidder.25 In one instance, former logger and subsequent park ranger Bill Roland claimed that an overhead skidder up from Ravensford had transported logs 5,000 feet from the mountain where the trees were cut to the one where the skidder was set.26 These innovations made logging the steep slopes cost effective and allowed companies in the mountains to compete with companies logging less demanding topography.27 The downside was that these technologies tore up streams and slopes and left masses of waste timber as well as other vegetation to die and dry. Incline railroads and overhead skidders even devastated areas without merchantable timber because they required removing trees that would interfere with their operation. Given seasons of heavy rain, the aftereffects of logging were increased erosion and poor regeneration of the forest. The slash made ready kindling for fires that could be started by sparks from the railroad tracks or from the engines.28 Of course, lightning and farmers’ seasonal fires to clear pastures could cause fires, too.

Champion Fibre axe men with crosscut saw, 1915–20.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

But the cutting itself was something. Once Champion Fibre bought out other companies after the sale of Champion Logging, it built a narrow-gauge railroad along Oconaluftee River and had a line up Kephart Prong. Logging reached almost to Mount Kephart on the state line. Carl Lambert was the son of a couple who ran a camp high up Kephart Prong. He described rail lines up Sweat Heifer Creek and to the falls. He stated that “a flume ran up the creek above the fall” to bring pulpwood to the cars. Higher up, the railroad crossed a high trestle across what Carl called Mud Creek (which must refer to today’s Icewater Spring) switching back and reaching an incline at the head of the creek. At that point, overhead skidders could transport the cut spruce timber between Newfound Gap and Dry Sluice Gap to cars. Additional spur lines and switchbacks were temporarily built to reach other coves. About 2,200 acres of spruce were cut from this area. The cutting was so complete and destructive that during the dry summer of 1925 a massive fire burned up over the crest of the Smokies into Tennessee. So fierce was the fire that it consumed green trees and all ground cover, sterilizing the land.29 Even later, heavy rains washed out the burned soil and created the popular landmark of Charlies Bunion, a famous rock outcrop along the Appalachian Trail. Shortly after its creation, park advocate Horace Kephart named the outcrop for the sore toe of his hiking companion Charlie Conner. Conner was a mountain guide, one-time logger, and son of Dock and Margaret Conner, who lived at the mouth of Collins Creek.30 How ironic that the great landmark, which provides sweeping views of the park, is the result of clear-cutting.

Champion’s railroad on the Oconaluftee continued up Beech Flats, forking off from the line up Kephart Prong. Of course, the Beech Flats land had been previously owned by Three M and Southern Spruce, and these companies had already cut the hardwoods. Champion Fibre then cut the spruce and any remaining small hardwoods.

Along Bradley Fork and up to Hughes Ridge, good hardwoods stood on the 5,500 acres of a piece of land called the J. A. Martin tract. Champion Fibre sold the stumpage of this area to Charles Badgett and William Latham for $150,000 in the 1920s. The Badgett and Latham Lumber Company cut about 28 million feet over three years and used incline roads in conjunction with a four-mile railroad from Smokemont to transport the timber. Richland Mountain, which lies between Kephart Prong and Bradley Fork, later endured fires that burned 454 acres. Though it is impossible to calculate the total amount of timber removed from the western tributaries of the Oconaluftee River, company records show that between 1920 and 1925, Champion Fibre sawed nearly 117 million feet of timber at its mill in Smokemont. Thirty-seven percent of this timber was spruce, 34 percent hardwood, and 29 percent hemlock.31

On the Ravensford side of lumber operations, Parsons Pulp and Lumber Company moved up Straight Fork with a railroad all the way to Round Bottom and Balsam Corner. Parsons cut hemlock and spruce from Dan’s Branch, a high tributary of Straight Fork, in 1918–19 but left standing the virgin spruce at the head of the stream. The company extended a spur line west from above Round Bottom into lower Raven Fork. It cut 144 acres just above the reservation. Yet another line followed Ledge Creek out of Round Bottom through Pin Oak Gap and into Haywood County. By the end of operations, three-fourths of the timber along Straight Fork was cut, though a lot of timber was never removed. By this time the mill at Ravensford was working night shifts to meet a production goal of 3 million feet a month, and it was selling pulpwood from cutover land to Champion Fibre for $1.50 a cord. It was racing to get as much timber out as possible before condemnation deadlines for the establishment of the park arrived.

Also on the eastern side of the valley, Suncrest Lumber Company logged Bunches Creek, Heintooga, Indian Creek, and Stillwell Creek by way of a railroad coming within a mile of the Ravensford line at Pin Oak Gap. Today, this railroad line exists as Heintooga Ridge Road and Balsam Mountain Road. The timber from this area was transported to a mill at Waynesville through Maggie Valley. It did not go to Ravensford.32

Though some Raven Fork areas were intensely logged, others were left to stand. Ravensford Lumber Company papers show that among the 212 million estimated board feet along Raven Fork, fewer than 1 million were cut. Similarly, by 1930, Champion Fibre Company left more spruce than it cut.33

SMOKEMONT AND RAVENSFORD

Up in the mountains, loggers lived in temporary camps that moved with the cutting. When the railroad reached these camps, railroad cars could be driven up to the camps and unloaded near the line as housing for the workers. These temporary camps were called string towns, and the railroad lines were colloquially called strings. Unfortunately, few accounts of these camps in Oconaluftee are available to provide more detail about what life was like there, whether they often included families or mostly just the timber cutters, teamsters, and men who worked the skidders. Local historian Carl Lambert has written that his parents ran a camp for Champion Fibre up Sweat Heifer Creek, and he commented that he “had many fond memories of fishing in this clear mountain stream … [and] caught my first speckled trout” there during the summer of 1924.34 Given that this area was clear-cut, it is hard to picture how idyllic the scene may have been. Perhaps some part of the stream was not logged, at least for a time, that summer.

In any case, the resident population of the valley surged during the logging years, increasing from 1,650 to 2,724 between 1900 and 1920. About 480 men were employed in logging and railroad jobs in 1920, and the industry also brought in store clerks, people to run the boardinghouses and hotels, cooks, teachers, ministers, doctors, and a dentist—as well as their families.35 A large portion of these new residents lived either in Smokemont or Ravensford, the company-owned mill towns built as processing plants for the timber, as business centers, transport hubs, and a community for loggers’ families, mill workers, supervisors, and visiting company managers.

Both towns were located on flat bottomland that had been farms before. Ravensford land was owned by the logging company, but Smokemont was leased from Wilson Ensley Queen and his second wife, Alice Queen. The lease stipulated an annual payment of $400 for “all the level land” from the river up to the boundary line with Aden Carver’s property. A large two-story Queen home and garden were excluded from the lease with a boundary just above a spring branch near the house. But the family’s cornfield became the site of the sawmill.36 The Oconaluftee Baptist Church already stood in its current place south of the Queen home. This frame structure had been built higher up the slope than the church located on the same plot of land in the 1880s. The church’s land had been previously donated by the Queen and Beck families. This new structure replaced the old log church around 1912; it soon adopted the name of the logging town and became Smokemont Baptist Church. Near the church stood the Smokemont school, also a frame building, situated just on the south side of the church grounds on a bank above the east side of the river. Today, Tow String Trail crosses this site. Smokemont school was a low-slung building with an overhanging loft at the front door. It stood on beam supports over the slope of the hillside. On the south side, five large windows were ornamented with bluebird boxes posted between each one. In time, additional schools were needed to teach all the children. At least five were near Smokemont during logging’s peak. A one-room school stood at the mouth of Mingus Creek and another about two miles up; yet another served those living up Tow String.37

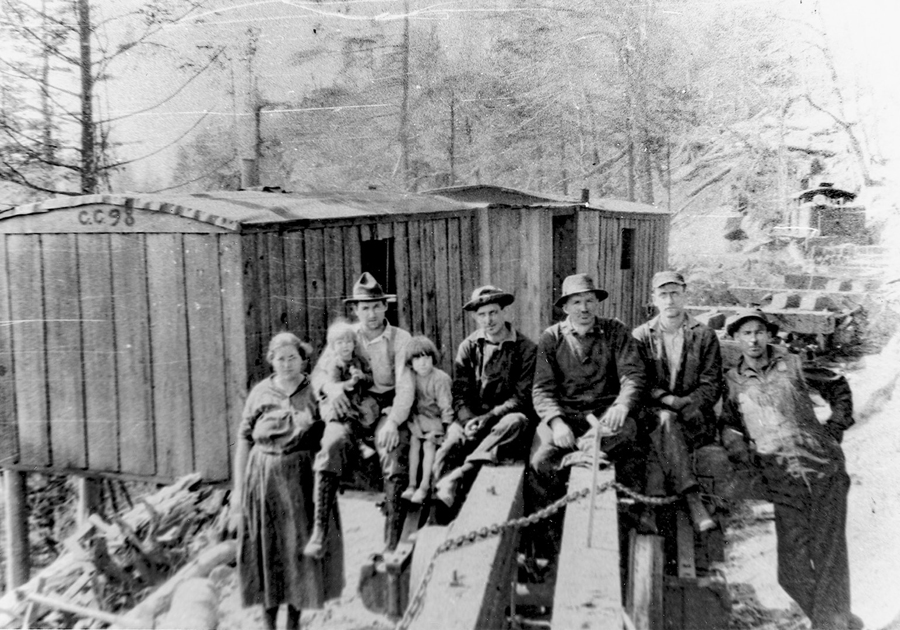

Champion Fibre employees in front of their boxcar homes, 1920.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

Ravensford School, 1938.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

Ravensford also had at least two churches, the Holiness Church and the Ravensford Church. The Ravensford school was a large, rectangular two-story building with an upstairs gymnasium that also served as an auditorium and was outfitted with a movie projector. The building featured very tall windows on the long front and back sides of the building. Like Smokemont, Ravensford also had satellite schools throughout the area; one was fancifully called the Submarine School because it was located near where a railroad bridge had fallen into Straight Fork. Ravensford high school students were taken to a Swain County school at Whittier by way of a bus converted to run on the railroad tracks. This converted bus went as far as Ela. From there students were transported in a regular bus via state road.38

Both Smokemont and Ravensford logging towns were constructed around large double-band sawmills, mill ponds, lumberyards, and railroad tracks. The railroad tracks of the Ocona Lufty Railroad and Appalachian Railroad, respectively, came into the mountains to the loading areas of the lumberyards. These were common carriers with passenger cars. Logging railroads extended from the mills up to the cutting areas. Once Champion Fibre was in charge of Smokemont, it bought a band mill at Waynesville and moved it to the logging town, adding to or replacing one already on the site. The band mills represented an important mechanical innovation that allowed lumber companies to handle large logs and reduce waste. Band mill blades were significantly thinner than those used in sash and circular saws; consequently, they were also more accurate. The output of the Smokemont mill was almost 117 million board feet, and its daily capacity was 80,000 board feet between 1920 and 1925. The Ravensford mill, which was a huge, barnlike structure, was capable of sawing 2 million feet of hardwoods or 3 million feet of spruce or hemlock per month.39

White men working in the lumber industry typically were paid a dollar for a ten-hour day, while Cherokee men were paid thirty-five cents. Often this pay was in company scrip or aluminum coins called Doog a Loo, and these were accepted at the company-owned commissaries located in the logging towns.40 A portion of workers’ wages were withheld to pay for health care from the company doctor, who visited each town periodically and could be called to a home in case of injury or sickness.41 Mill work demanded long hours part of the year but perhaps few or none for cutters and teamsters when winter snows covered the slopes. Florence Cope Bush’s account of the life of her mother, Dorie, notes that her father, who worked at the Smokemont mill, experienced both long shifts and weeks off work during the winter.42 It is difficult to know how steady the work or adequate the pay was for most of the employees. Photographs of the mill crews at Ravensford show thirty to forty young to middle-age white men dressed in boots, overalls, shirts, and caps or hats. A photo of a Smokemont crew is similar but includes fewer laborers, only a dozen. They would have worked as sawyers, millwrights, saw filers, and laborers. Though not pictured in the photos, about three dozen Cherokee men also worked in logging, either in the mills or in the mountains as timber cutters. Most of the Cherokees worked for the Ravensford firms. Fewer than ten African Americans are listed in the 1920 census as residents in the valley and employed in logging, though an additional dozen African American residents were employed as section workers for the railroad, and four were employed as teamsters.43

The mill towns were far more connected to the larger society than anything previously seen in the valley. Maisie Queen Young was the granddaughter of Wilson Ensley Queen, who owned the Smokemont land. She grew up in the community and recalled the town as “booming.” Both Smokemont and Ravensford had electricity and telephone lines. Each had a company commissary, a general store with a post office, an infirmary, a boardinghouse, a hotel, and a clubhouse for company managers, though none of these essential buildings was built for aesthetic appeal. They were plain and serviceable. The Ravensford commissary sold beer and soft drinks. A six-ounce Orange Crush was its most popular item, according to logging hands.44 In Smokemont, the doctor’s and dentist’s offices were located in the commissary, but in Ravensford the infirmary was situated in a separate building near workers’ quarters, away from the center of activity. As recreation, the towns held Cherokee stickball matches on a playing field in Ravensford, with contests between town teams and with Cherokee teams.

The candid memoir of Leonard Carson Lambert Jr., a Cherokee, provides rare insight into alcohol consumption among loggers and others at this time. He claimed that loggers and farm families (both white and Cherokee) consumed moonshine. Despite religious talk against it, folks in the valley liked alcohol but did not like “legal alcohol.” His grandmother made a good living making and selling moonshine during the 1920s, and he states that someone in almost every Cherokee family did as well. Bootleggers paid off police to avoid being put out of business and jailed.45 It seems reasonable to assume that other families besides Cherokee ones also made and sold moonshine in the valley, but I have not discovered sources stating that was the case. Certainly many farmers had grain fields and orchards that would supply ingredients for their brews.

Both towns were surrounded by a range of housing for mill workers, loggers, and company managers. A railroad map of Smokemont from 1919 shows that fourteen three- and four-room dwellings stood on the north end of town near a mill pond. An additional seven smaller dwellings were located on the south side of town, below the Queen home and the commissary. The line of these smaller homes extended as far as Smokemont Baptist Church. Three additional, larger homes lay between these small dwellings and the commissary; one was adjacent to the commissary and was occupied by its manager, and the other two were the largest—five rooms and a bath—and set apart from all others. Maisie Queen Young recalled a large clubhouse, boardinghouse, and “rows and rows” of company houses across the river from the mill. Another descendant recalled that each section of Smokemont was named, some for boroughs in New York City such as the Bronx, and others with such names as Sandtown and Pumpkintown. These must have been built later; a photograph shows a rather densely built town. Other workers lived in log cabins in the surrounding valley. For example, Lila Maples and Robert Vance Woodruff lived in a cabin on their relative Aden Carver’s land for a while when Robert worked at the Smokemont mill; later the family moved closer to the father’s work and rented a farm near the Cherokee Boundary.46

Champion Fibre’s mill and town at Smokemont, 1920.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

The town of Ravensford was more compactly arranged than Smokemont with town buildings along the upland areas surrounding the railroad lines. It had more than seventy dwellings of various sizes; they were painted white and sported green shutters, but they were made of rough lumber. About half of these must have been small indeed because they are labeled “shacks” on a map. Others seem large enough for three or four rooms, and some of these had two stories as well as root cellars. The largest dozen homes were likely twice the size of the midsize ones.47

Despite their modern utilities, the towns retained some rural features. One was the proximity of fields to the town. Mescal Burke grew up near Ravensford and recalled playing with the store owner’s daughter. Prominent in her memories were that her father’s cornfield was right across from the store and that store customers could use a bathroom attached to the house alongside the store. The toilet, she said, had a wooden seat. Also, Hazel Caldwell Bryson’s father worked for the mill, but as a child growing up on Tight Run, she swam in the Oconaluftee River and recalled her family canning blueberries, grinding its own corn, and raising chickens. But her parents bought sugar, coffee, and flour at the store. Similarly, families used mountain remedies such as moonshine, poultices, and castor oil for illnesses. Farmers traded their surplus apples, honey, ham, and corn for store groceries. Some Cherokee women sold their handmade baskets to the stores for others to purchase for cash or in exchange for flour, sugar, and canned goods, beginning the craft trade for the Cherokees. Fishing remained a pastime and a way to supply dinner because it could be done near town. Hunting declined, though some farmers continued to hunt on occasion for game; bears were hunted to discourage them from attacking livestock.48

Bridges across the river and its major streams, which could be deep and fast, presented another juxtaposition of old and new. There were numerous log and swinging bridges, some stabilized with wires and handrails, some not. Stories of adults and children falling from bridges into the river in winter or in wet weather were not uncommon. Aden Carver’s granddaughter told a story about Aden pulling a prank of crossing a log bridge on his hands and knees in front of city folks; she said that he could easily walk across but wanted to trick visitors into thinking he could not.49

Both communities eventually got bridges that could bear the weight of vehicles. In 1921, Swain County built three steel-reinforced, arched concrete Luten bridges across the river, opening the mill towns to auto traffic and providing pedestrians a broad, reliable crossing. Luten bridges were patented by Daniel Luten and the National Bridge Company in Indianapolis, Indiana, but these were constructed by the Luten Bridge Company in Knoxville, Tennessee. One bridge crossed Raven Fork and marked a swimming hole just above it, near today’s park boundary. Another crossed the Oconaluftee near the Mingus home (about a half mile north of the current visitor center). This was the longest and included three spans. It was demolished in 1982. A third crossed Bradley Fork at Smokemont and stands today but is open only to foot traffic. It is located where the Smokemont Loop Trail spills into the lower end of the campground.50 The Luten name can be seen on a relief inscribed into one of the bridge’s abutments. The design of these Luten bridges was sleeker and more metropolitan than those constructed in the 1930s for the national park. They looked like they belonged in cities. Later, park-era bridges had a rustic timber or hewn stone design, which marks them as the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

LIVING “ON OWN ACCOUNT”

In 1910, a new question appeared on federal census sheets. In addition to recording occupation and industry, census takers began asking whether someone was an employer, a salary or wage worker, or a person working “on [one’s] own account.” The item appeared just in time to capture labor changes caused by logging in the park. By 1920, the number of wage workers in the valley had skyrocketed because of the influx of people for the logging companies and the railroad. Nonetheless, the established families continued to farm. Though a young man in a family might be listed as a logger and wage laborer or even as a wage earner on a farm, the male heads of the farming households were listed as working “on own account.” They remained masters of their own fates. For the most part they made their living farming their own land as they had since the Civil War. As always, they sought multiple sources of revenue and subsistence, growing corn, keeping hogs and bees, raising cattle, and seasonally harvesting timber and chestnuts. Though often unrecognized and certainly undervalued, the women in these households contributed significant labor and products toward the family’s health and wealth. Women processed and preserved food, wove fabric and made clothes, tended livestock and sold or bartered surplus goods at local stores—in addition to “keeping house,” which included cooking, cleaning, laundry, and childcare. Most of what these families needed to survive they could raise themselves; necessities they could not produce, they could barter for or buy. In Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers, historian Ronald D. Eller explained that for mountain families “land held a special meaning that combined the diverse concepts of utility and stewardship. While land was something to be used and developed to meet one’s needs, it was also the foundation of daily existence, giving form to personal identity, material culture, and economic life.”51 This view helps us speculate how the farmers understood the arrival of commercial logging and the changes that industrialization brought into their lives.

Twenty-first-century park visitors cannot know if the mountain families grieved the loss of the wilderness that they had lived within. Once the clear-cutting around and upslope of their farms began, they seem to have adapted readily to changing ways to make a living. That Wilson Ensley Queen would lease his best bottomland to a logging company for a sawmill and company town can be understood in this way. Also, the Floyd family leased large tracts of land along Mingus Creek to a logging company. Bert Crisp, who had a farm along Mingus Creek, worked for Geissell and Richardson, which logged that area. Nineteen landowners in the valley agreed to right-of-way leases with Champion Fibre Company in March 1917 so that narrow-gauge railroad lines could reach timber-cutting tracts high up Bradley Fork, Kephart Prong, and Beech Flats. The Becks, Wilsons, Treadways, Conners, Gibsons, Reagans, Carvers, Bradleys, Kimseys, and others signed agreements allowing thirty-foot-wide corridors across their farmland for annual rents of five to fifty dollars. The range in rent seemed generally consistent with the anticipated length of the corridor across a particular farmer’s land. The contracts included a statement that the surveyor would seek a route doing as little damage as possible to the landowner’s buildings and fields but made no promises that the railroad would not disrupt the original arrangement of the houses, outbuildings, or fields and pastures.52

Two years after these agreements were struck, Champion saw that it needed to expand its lines and made additional agreements with the Queens and Carvers. The Queens agreed that a rail line could be built on land adjoining that of the original Smokemont lease. The track would cross a “strip of the garden,” skirt the side of the Queens’ barn, and approach the Queen home. This new lease was purchased for an annual rent of fifty dollars as well as two “considerations.” One was that the lumber company would cover the barn’s roof, two ends, and one side with a “fire-proof material.” Champion would also carry a $2,500 fire insurance policy on the Queens’ home and barn, with sole responsibility for paying the premiums.53

Champion contracted with Aden and Martha Carver to “construct and erect a dam and pipe-line on and from their land containing 199 acres, more or less, on Carver’s branch a tributary of Ocona Lufty River in Swain County, N.C., through and over said lands to the reservoir and log pond now used by the Champion Fibre Company, party of the second part, at its mill yard near the mouth of Reagan’s prong of the Ocona Lufty River.” The arrangement allowed the company to pipe the stream’s water to the reservoir at Champion’s mill yard for its log pond. The cost of this agreement for a term of thirty years was “One and no/100 Dollars, and other good and valuable considerations to them in hand paid by the Champion Fibre Company.”54 It’s impossible not to wonder what the unspecified considerations may have been to allow the lumber company this high level of access and impact on a family farm. In any case, they must have been desirable and not too disruptive because the Carver family remained in the valley throughout the logging years and long after Champion decamped. And even though Aden was farming in 1920 in his early seventies, his sons, Julius (age forty-three) and Mack (age twenty-four), were both cutting timber, as was Julius’s son Otis (age eighteen). As further evidence of their adaptability, the 1930 census lists Aden as a renter (by then from the park service, since he had sold his land) and a sawyer working in a sawmill, likely Champion’s at Smokemont.55

One branch of the Conner family, the one headed by the Reverend William Henry Conner and Rachel Gibson Conner, also demonstrated the ability of the established Oconaluftee families to adapt to changing times. Their son, Dock Franklin Conner, farmed at the homestead for many years, but when tourism picked up in the 1910s, he opened his home as a lodge and served as a mountain guide on occasion. In the 1930s, he paired up with Wiley Oakley, perhaps a distant cousin, who had a guide business in Gatlinburg and became the quintessential mountain guide in the years before the park was established. On the first day of an excursion from Gatlinburg, tourists would travel to Dock’s home for room and board. From there, Wiley would lead a party to Cherokee the next day. The return trip included a second stay over at Dock’s. Two of Dock’s sons, Jaheu and Charlie, also responded to shifting opportunities in the valley. In the early 1920s, both worked as unspecified laborers for the logging industry. By 1922, Jaheu and his wife, Nellie Bradley Conner, were running the general store in Smokemont. This arrangement outlasted the logging era. Younger brother Charlie ran a meat market and supplied beef, presumably from his family’s cattle, to be shipped by rail up to the logging camps. He, too, became a mountain guide, known for the sore toe that gave Horace Kephart the idea for naming Charlies Bunion. By 1930, Charlie had returned to farming.56

For a time in the early 1920s, a local man known as a bear hunter worked for the Conner family. Cole Cathey led the cattle to grassy areas for grazing after land had been logged. According to an article by Vic Weals, he would leave salt for the cattle as a way to anchor them to an area. Because these locations were high, they were also the haunts of bears. So Cathey always kept high-power rifle cartridges inside his waterproof coat, in case he needed to shoot a bear that was threatening the cattle. One day, Cole was helping to get hay in from a field along the river when a thunderstorm came. Dock hurried into the barn with the horses, but Cathey paused to fashion a sort of umbrella with a pitchfork and hay. This was a bad idea. When he did not come in for supper, Dock sent Charlie to look for Cathey, whom he found dead from a lightning strike. The force of the bolt shredded his clothing, exploded the rifle cartridges in his pockets, and stopped his watch at 5:30. Cathey’s death certificate states that he died in the employment of D. F. Conner from an accidental lightning strike on July 12, 1922. He was six days short of his thirty-eighth birthday.57 Somehow this tale is memorable not only for itself but also for the brevity of life and the events that characterize an era.

Perhaps the most complete account of how families continued to farm after large-scale logging began came from Dan Lambert, a resident of Tow String. During an interview conducted in 2004, Lambert provided a glimpse of home and farm economy:

My mother was Cora Bradley Lambert. She was raised down here at what we call the Bradley place, down just below the [Tow String] church. And my father was a Lambert. He’s Monroe Lambert’s boy, and that’s my grandpa. Of course, they lived here on the creek I reckon all their lives, and were raised here. And he farmed all of his life. And my mother gardened, made the garden, kept the house, and canned. She put up a lot of canned stuff. Blackberries was one thing and garden vegetables out of the garden. She kept a lot of chickens and we sold eggs to more or less buy our groceries or what we have to have. All we needed was flour and coffee and a little bit of sugar and lard and that’s about what we bought. Most of the time, we raised our lard and kept and processed it out of the hogs.

So, my dad, he farmed all the time. They’d get out wood. It was chestnut wood. We called it acid wood at that time. And they’d get out a few logs and sometimes they would cut white oak for stave timber, to make barrels out of. It sold pretty good. We sometimes cut tan bark and [used] the white oak logs, we’d take the bark and sell it for tanning material. And of course, other than that, well he pastored church about all of his life. He farmed and pastored. Even down at Bethelberry [Bethabara Church] … Echota, the old Echota church. And Rocksprings Baptist Church. Up at Smokemont, he was the last pastor that pastored at Smokemont.58

Despite the influx of new people and technologies, farmers working on their own accounts continued much as they had. In addition, they opportunistically developed ways to bring in cash that helped them buy what they could not grow or make. When it was convenient, they engaged with local businesses, but typically they did not become dependent on others. They still had their land to use as they saw fit. Is it any wonder that once they had endured logging that they felt unfairly targeted for their most precious resource, their land, when park proponents began to hold sway in public debate? The notions of wilderness preservation and outdoor recreation as legitimate purposes for their property were entirely out of keeping with their lives.

The logging era brought dramatic changes to Oconaluftee, but it was in full swing less than twenty years. The spectacle and waste of clear-cutting and wildfire raised the concerns of people who wanted to preserve the southern Appalachian forests, particularly since the northern forests were gone. For the most part, this effort was led by a group of well-off, even elite regional leaders who saw a national park as a means of social progress and economic development through tourism and the hospitality industry. Residents of the valley would have been content to keep their farms; there is no record of their desire for the establishment of a national park to protect the mountain wilderness that they had lived in for a century. Though North Carolinians initially preferred a forest preserve over a park to protect the important timber resource, eventually the idea of a national park in the East caught hold, and passionate and indefatigable park advocates such as Horace Kephart succeeded. Congress authorized the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in 1925, an act that signaled the beginning of the end for logging. Logging stopped at Ravensford in 1927 and in Smokemont in 1931. Completing the land condemnations, after complex surveys, assessments, and protracted legal wrangling, would take longer.59 Champion Fibre negotiated a sale price for all of its property in the park boundary, a total of nearly 93,000 acres (with about 52,000 in North Carolina) for $3 million in April 1931. A final judgment in the lawsuit between the Ravensford Lumber Company and the state was announced in November 1933, paying the company $1,057,190 for its 33,000 acres (including the town of Ravensford). The company was allowed six months to remove its property from the area and use the railway to do so. However, it was not allowed to cut any additional trees or cause damage to growing timber. At the same time, the Appalachian Railway was awarded $50,000 for its land in the park and also given six months to remove property, including the “steel rails, cross ties, side tracks, switch bars, [and] switches.”60

Once logging operations ceased, most of the mill workers and timbermen and, of course, their families were forced to leave the area, having no other means of making a living and no land to return to. Some left suddenly and neglected to pay Oscar McDonald, the Ravensford store owner, their tabs. Bryson City was the destination of some folks. Others eventually were hired by the park. Some of the houses in Ravensford were sold at auction and moved out of the park boundary within a couple of months. The hotel remained and was used for a while as a camp.61

The stories of those who owned farms and leased land were typically more complex. The park service assessed their land and made offers. Some accepted these offers, but others contested the assessment values in court. However, the timing of the condemnation proceedings was miserable for many. Once a price was reached and the sale was complete, the depth of the Depression was upon the nation. Bank runs, failures, and closures left former small landowners without access to funds or, in some cases, without funds at all. Maisie Queen Young claimed that her grandfather’s land, which included Smokemont and more than 500 acres, averaged a price of only twenty-five dollars per acre. But “hardest part” of the whole situation was that after her family was paid, all the banks closed and they had nothing to use to buy another home.62 This circumstance led the National Park Service to authorize lifelong leases to residents beginning in 1932. These provided the farming families the ability to stay on their land and in the homes they had built. Rents for owners who accepted the park’s valuation of their property were very low, but those who contested the sale price were charged more. Smokemont Commissary clerk and postmaster George Beck was one who resisted the deal offered to him for his farm and was seen as causing “all of the problems for the North Carolina Park Commission at Smokemont.” So in turn he was charged full rental for his land and home after condemnation. He eventually moved to the Qualla area of Cherokee and bought the old store that had once been owned by Will Thomas and that housed the Qualla post office. Once the park was established in 1934, leaseholders could not graze animals, fish, forage, and hunt as they had traditionally done.63 Their ability to make a living off their own land was severely constrained. These residents took work where it was available in mills, in the CCC after it was established in 1933, and in the park service during the late 1930s and after.

Carl Lambert had lived in a logging camp high up in the Oconaluftee Valley in the 1920s when his parents ran the camp. In 1970, he visited the Sweat Heifer Creek area again to dig ramps, which the park service then allowed locals to do seasonally. His reflections on that return trip capture the dramatic change that took place at the end of logging: “Many were the stories of storms, wrecks, and people brought to mind. It seemed in my mind I could hear the old steam engines pull up those steep grades, the cry of the steam whistle, the ringing of the choppers axe, the crosscut saw and the cowbells. But these were only dreams of an era gone by.”64

Though he rather wistfully recalled the sounds and excitement of this period, another scene checks the nostalgia for logging days. Imagine the end of the logging era as a steam locomotive pulls away from the Ravensford or Smokemont station. Alongside are trucks and automobiles, commercial signs for gasoline, and electrical lines—all the trappings of an industrialized city. What might the Oconaluftee Valley have become if the park movement had not been successful? Logging would have ended anyway once all the accessible timber had been cut, say within another decade. More mountains would be shorn of trees and likely more fire damage would have occurred, even though by the 1930s the state was becoming active in promoting fire suppression and forest management. One can wonder if Ravensford and Smokemont would have become mountain towns (or even a single town) along the lines of Bryson City. Can we really guess what the valley would look like now without the coming of the park? Some families, no doubt, would have held on and found ways to continue farming or would have found occupations in an emerging town. Could that alternative reality possibly have been preferable to the biosphere reserve that is today’s park and that expands in three directions from the old Enloe farm, now the location of the visitor center?