Chapter 13

CCC TRANSFORMATIONS

FROM LOGGING CAMPS TO PARKLAND

▲ ▲ ▲

The first time I hiked Kephart Prong Trail was in the early 1990s, and I was almost rear-ended before I turned off Newfound Gap Road into the parking area. Descending from the gap, I did not know exactly when I would reach the trailhead, so I waited to signal a left turn until I saw the sign. The car behind me was pretty close and screeched to a stop just in time to avoid a crash. I count this as one of several times I’ve had a near miss.

Once my nerves recovered and I was parked and walking, the rest of the day was bliss. The trail offered simple joy upon understated delight, beginning with a log bridge over the Oconaluftee River and continuing with an easy incline along a broad path, flanked by wildflowers, ferns, and second-growth stands of two of my favorite trees, American beech and eastern hemlock (now threatened by an exotic insect). A few other people were around, but the way was uncrowded and the pace leisurely on a warm July Sunday. I was a hiker then, not much a student of the woods, cultural history, or park lore. Nonetheless, again and again, these disciplines presented themselves to me as I encountered evidence of earlier residents’, loggers’, CCC boys’, and conscientious objectors’ lives in my place of escape. Though not what I came for, the stone hearths, water fountain, boxwoods, cement structures, and abandoned rails made me feel as if I were finding forgotten and mysterious artifacts, kind of like my own personal Mayan temple discovery in a film about regional explorations. As an aesthetic, I was glad they were falling over and obscured by moss.

Since then, I’ve taken this trail a bunch of times, each one knowing more about it. Consequently, the detritus of prepark days conjures less wonder and more gratitude. I don’t want the remnants removed, but I do want them overtaken by the forest, mist, and sunshine. This sentiment may seem in conflict with the endeavor of chronicling the human history of the valley, though they intertwine for me. I find the stories of the valley entertaining because of the personalities of the residents, valuable as insights into past economic times, inspiring as tales of both individual and community resourcefulness and perseverance, explanatory of “how we got here” (meaning contemporary society and its struggles to overcome tribalism), and instructive as examples of the dependence of people on the natural world, in both sustainable and exploitive ways. Still, I know that I’ve prioritized people and cast the flora, fauna, and land in cameo roles. Just note how I still first recall my own driving story when this trail comes to mind. I live in my own head all the time, but hiking in a park bends my thoughts. The park helps me wake up to other species, the Smokies’ astonishing diversity, and human dependence on that diversity.

▲ ▲ ▲

EVEN BEFORE THE LAND condemnations and sales were complete, the National Park Service was on site and responsible for “protection and administration” of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in 1930, after North Carolina and Tennessee conferred 150,000 acres of land to the federal government. The following January, the first superintendent, Ross Eakin, arrived to oversee the construction of park roads, trails, campgrounds, and facilities essential to accommodate the visitors who had begun to arrive in large numbers, despite the Depression.1 The federal government recognized the terrible straits that mountain farm families and communities were placed in once their land was taken and bank runs and closures either robbed land owners of the sale proceeds or made bank funds inaccessible. Consequently, in 1932 arrangements were made—within the context of the park’s establishment—to help locals survive the transition, which had been aggravated by a precipitous drop in county property taxes. With the establishment of the park, three-fourths of Swain County’s taxable land was taken, and many families were forced to leave the area to find work. Congress passed a bill allowing former landowners lifetime leases on their farms so that they would have their homes and fields, at least, to live on, even though hunting, pasturing, and foraging were largely curtailed. Additionally, as part of an emergency relief act, Congress allotted $509,000 for roads, which allowed the park to hire local men to work on constructing Newfound Gap Road, the main overmountain artery of the park, connecting the primary park entrances of the two states. The North Carolina section was termed Road Project 1-B, with 1-A obviously referring to the road on the Tennessee side.2

These measures likely helped tide folks over, but it was not until after Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office in 1933 that significant relief programs got underway. Very quickly after the inauguration, the Roosevelt administration created Emergency Conservation Work camps, which in 1937 became known by the familiar name of the Civilian Conservation Corps. As early as April 1932, the government established enrollment quotas by county that would determine how many young men could join. Both county population and degree of destitution were considered in the formula that led to the formation of a handful of companies of 200 men each and located in Oconaluftee Valley. The park benefitted tremendously from CCC work and hosted the most companies of any national park, with the total reaching eighteen or twenty-two, depending on how the count was made. The existence of spur camps and double camps and the transfer of camps to other locations makes a simple count of camps tricky. Oconaluftee Valley was one area of the park that hosted camps throughout the CCC era.3

By June 1932, enrollees began arriving at Smokemont as members of NC NP-4, Company 414, also known as Camp Will Thomas, in recognition of the nineteenth-century merchant who became a Cherokee agent, state legislator, and the head of the Confederate Thomas Legion during the Civil War. The company included 132 Swain County residents. A second group, NC NP-5, Company 411, enrolled 126 North Carolina boys at Camp Kephart Prong. These regular enrollees were male, white, physically fit, unmarried, unemployed, and between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five, a range that was later expanded to seventeen to twenty-seven years of age. They agreed to remain in camp for six months and were paid thirty dollars a month. However, all except five dollars of the pay was sent to the enrollees’ homes to help their families. Although some African Americans were enrolled in the CCC, local resistance prevented them from being located at Smokemont, despite plans to do so in 1935. Similarly, 150 Cherokee youth formed a separate company supervised by the Cherokees and administered through the Office of Indian Affairs, but limited funding for the Cherokee company allowed enrollees to work only half time, significantly decreasing the aid that reached this community. Cherokee CCC men completed projects similar to those within the park, but theirs were located within the Qualla Boundary. Nonetheless, enrollees from northeastern states were placed in Oconaluftee. Within the first six months, a company of mostly Italian Americans arrived from New York, New Jersey, and Delaware. They comprised the NC NP-14, Company 1211, at Smokemont. Their lodgings were along Mingus Creek, and they became known as the “Wop Brigade” because of their heritage. Additional camps were established as time passed, including NC NP-15, Company 1215, also located at Mingus Creek. After Company 1215 was relocated to the western states in August 1935, another company arrived, Company 4484, and stayed three months before moving to Deep Creek and becoming Company NP-16. Finally, two companies were established at Ravensford, NC NP-18, Company 1259, and NC NP-19, Company 426, which was known as Camp Round Bottom. This camp, so named because the area was a round valley floor, was largely inhabited by New Yorkers.4

Early on, additional local relief came in the form of a program to hire older residents known as Local Experienced Men, who had local knowledge, useful skills, and relevant work experience. This expansion of the basic CCC membership brought maturity to the ranks and dampened concerns about outsiders taking work away from locals (such as those in the Wop Brigade).5 Among these men were Oconaluftee stalwart Aden Carver, then in his early nineties, who traveled to Sugarlands to join and was sent back to the valley to serve, and Charles Bascom Queen, the son of Wilson Ensley and Alice Queen, the formerly land-rich family who leased Smokemont to Champion Fibre Company to use for its logging camp. Charles’s daughter Maisie later explained that her father “worked in the shop” of Company 1211 when she was a high school senior.6 He may have been one of the local men who helped the New Yorkers adjust. In January 1934, the associate engineer for the CCC wrote, “The work is progressing nicely in this camp [N-14]. Am happy to say that since the enrollment of the local men in this camp, the New York boys have improved two hundred percent. The health of the company is good, quarters comfortable. The men are well clothed and happy.”7 Roy Minyard Conner, the grandson of Joel and Katherine (Mingus) Conner, and Ed Bradley, a son of one of the Bradley families, were also foremen in CCC camps in Oconaluftee.8

The economic benefits of the CCC reached other locals as well because the camps needed large quantities of food for the men. As early as August 1933, a farmers’ cooperative was formed to supply these needs in Swain County. During one week, “1,700 pounds of Irish potatoes; 20 dozen ears of corn; 250 pounds sweet potatoes; 100 pounds each of squash, turnips, tomatoes, and onions; 260 pounds of cabbage; a bushel of peppers; and 28 dozen carrots” were purchased from the cooperative for the nearby camps.9

When the first camps opened, the accommodations were primitive. That first summer, housing at Smokemont amounted to World War I surplus tents lined up in a field. But these were soon replaced by barracks and other military-style buildings such as a mess hall, an administration building, an infirmary, and officers’ quarters. Except for the post office and store and the two-story school building, the homes and buildings in Ravensford were dismantled and their lumber was repurposed for CCC buildings. The school was also torn down in 1938.10 The camps looked quasi-military, usually arranged around a flagpole and company sign. Interior photographs of the barracks and mess hall show long rows of bunks or tables with wood stoves for heat. A gas generator was used for cooking. The ceilings were low, and the rooms looked dark. Later photographs of the rec halls and study areas, however, look much more inviting, with the former having a pool table and the latter having desks, tables, and displays of books and magazines. Camp enrollees adapted the grounds for sports; the baseball field from the Ravensford logging town was put to use for CCC team games, and a makeshift outdoor boxing ring—mostly a level square outlined with stones—was created for matches among enrollees between camps. In 1940, a subdistrict Golden Gloves competition took place at Ravensford. The contenders in the Golden Gloves matches included names from valley families (Jenkins, Dowdle, Pressley). The Smokemont Baptist Church welcomed CCC boys for services, and Saturday “liberty parties” to nearby Sylva and Bryson City provided enrollees chances to visit these towns, shop, or go on a date.11

In a memoir about his time as a Smokemont enrollee, Frank Davis, who came from the central Piedmont of North Carolina, described the frequent weekend dances held at the rec hall with live orchestras playing big band music. Invitations to local young women were sent by mail. Frank met his bride, Elizabeth Sherrill of Sylva, at such a dance. Her maiden name suggests that she was a descendant of Samuel Sherrill, one of the families that settled in Oconaluftee Valley early in the nineteenth century.12 The camps certainly provided lots of new, eligible young men for the local young women.

Life in the camps was somewhat regimented; after all, the CCC was initially administered by military officers. Even so, it provided the young men with housing, army-issue clothing, filling meals, jobs, training opportunities, fellowship, and camaraderie. The five-day workweek began at 6:00 A.M. with reveille, included eight hours of work plus a lunch hour, and ended with lights out at 9:45 P.M.13

Smokemont CCC Camp NP-4, 1933.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

ALL MANNER OF PHYSICAL LABOR

The work projects of the CCC in Oconaluftee remain visible today; they transformed the valley into parkland, helping the land recover from the erosion, fire, and habitat destruction of the logging era, and provided landscaping, road work, and trail maintenance essential to the new park. A report for NP-4 at Smokemont from the first enrollment period of about three months claims that 8,543 “total man days” were spent on conservation work, 2,489 days on camp construction, and 2,116 on housekeeping. During the same period, this company removed fire hazards from 1,960 acres, landscaped eight acres, cleared fifteen miles of roadsides, and maintained one mile of road; the group also improved three miles of truck trails, eighteen miles of horse trails, and five miles of streams. In addition, one hundred man days were spent clearing the campground, and two were devoted to collecting a half-bushel of seeds for later cultivation.14 This account shows that the work often included significant outdoor physical labor using saws, axes, picks, and shovels for digging, planting, and grading slopes. The days working on the campground were spent cleaning up the debris and burying the remains of the defunct sawmills and railroad lines. Champion Fibre left an old locomotive and forty railroad cars on site in Smokemont when it decamped, as well as other heavy metal equipment for sawing logs. These had to be hauled away at the park service’s expense. Smaller debris was buried on site. Similar cleanup work from logging occurred at Ravensford and Mingus Creek.15

After the initial clearing was accomplished, more focus was placed on landscaping along Newfound Gap Road, where the NP-5 Company planted more than 11,000 trees and shrubs. NP-14 landscaped picnic areas in Oconaluftee that were being created for park visitors. Seed collection continued as part of NP-14’s tasks; these northeastern seaboard natives collected fifteen bushels of hardwood seeds.16 The seeds were taken to a CCC plant nursery in Ravensford, which was run by Eli Potter. Potter had previously been employed by the Biltmore estate in Asheville and was a big man with a bushy white mustache. Park employees later remembered him to be a keen observer of the natural world. At the nursery, Potter supervised the raising of seedlings for reforestation plantings and landscaping in the park and for pine tree seedlings used along the Blue Ridge Parkway, which also benefitted from CCC labor.17

In addition to these ongoing efforts, the companies located in Oconaluftee should be credited with completing three important construction projects: the rehabilitation of Mingus Mill, the creation of the fish hatchery at Kephart Prong, and the building of the Oconaluftee Ranger Station. Except for the fish hatchery, these remain intact and are key parts of the current Oconaluftee Valley experience for park visitors.

In 1931, Ed and Fred Floyd sold Mingus Mill to the park. It had been built in the late 1880s with the financing of Dr. John Mingus, their great-grandfather, and the oversight of their father, Lon Floyd, and their great-uncle Abraham Mingus. For over forty years it was one of the hubs of the community; residents came to have both corn and wheat ground. After the sale, the mill fell into disuse and disrepair. Fortunately, in 1936 and 1937, the park service architect working in the Smokies, Charles Grossman, led the effort to restore it into working order. He thoroughly evaluated the building, machinery, and external features of the mill and oversaw its restoration. The repair work on the mill’s component parts—dam, earthen race, timbered flume, and penstock—was extensive. Much had rotted and stopped working, so these components needed to be repaired and replaced. The mill building itself was in relatively good shape, except for the load-bearing framing of the north end. It had partially rotted and was weak from continuous exposure to water. Because the poplar and locust timber that had been originally used to frame the mill was no longer available—due to logging—chestnut timbers were used for the replacement of two plates, eight posts, and supporting braces. Grossman also dismantled and inspected the hydraulic turbine to assure that it was in running order. He found its overall condition to be acceptable. After replacing the driveshaft, the turbine was reassembled and put back into place.18

Eli Potter holding a red oak seedling at the Ravensford nursery.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

No doubt the mill restoration was immensely aided by Aden Carver, who had helped with the original construction of the mill under millwright Sion Early long ago. At this point, CCC “boy” Carver was over ninety. Grossman also interviewed Early, who was then retired and living in Waynesville. Younger CCC enrollees supplied the physical labor.19

Once the restoration was finished, the park leased the mill to John Jones to run as a tourist attraction. He hired other local help, Carrie Nations and Major McGee, as operators, and this staff ground corn for locals following the traditional standard of a one-eighth volume toll. This toll portion was then sold in Cherokee and Gatlinburg to defray expenses. Until Jones died in 1940, the mill ground 650–700 bushels of corn each year. At that point it again fell into disuse; no replacement miller was hired during the war years or even until the late 1960s, when the mill was due for another round of maintenance and restoration.20

At about the same time that work was underway at the mill, Superintendent Eakin received $20,000 in funds from the Works Projects Administration (WPA) to build a fish hatchery. The purpose of the hatchery was to rear fingerlings of both brook and rainbow trout to restock streams that had been overfished and were being restored after logging ceased. At this point in time, park administrators were eager to establish the park’s recreational facilities with sport fishing as a primary draw. Both WPA and CCC labor were used to build the hatchery, which was located along Kephart Prong above the camp of the same name. The camp included barracks, officers’ quarters, a latrine, a mess hall, educational and recreational buildings, and a woodworking shop.

The hatchery consisted of dozens of round, stone-defined rearing ponds spread across a grassy streambank as well as a small diversion dam and a pipeline for the water supply. Once fingerlings reached six inches in length, they were transported by ten-gallon milk cans to many North Carolina park streams. The brook trout were intended for streams at 3,000 feet elevation and above, and the rainbow trout were for lower-elevation streams. The current thinking by park biologists was that the native brook trout could maintain its numbers at high elevations, whereas the rainbow trout would thrive in lower streams and provide good sport fishing at the more accessible streams. Later biologists learned that elevation alone could not protect “brookies” from the larger and more aggressive rainbows, alas, and some of the stocking done in the CCC era led to losses of this native species in some streams. In any case, in the first several years, the hatchery produced between 38,000 and 250,000 trout each year, with the majority being rainbow trout. But as the operation continued, it was plagued by several instances of dramatic fish die-offs. At the time, the cause was not understood. Biologists speculated that cold water temperatures were the reason. But much later, scientists learned that the reason the hatchery became unproductive was that road construction had exposed Anakeesta rock above the tributaries that fed water into the rearing pools. When it comes into contact with air and water, Anakeesta rock creates a toxic mix of chemicals and lowers the water pH significantly. When the poisoned water reached the hatchery ponds, many fish died immediately; others were weakened and became vulnerable to disease. Eventually, the project was deemed unsustainable because of low productivity, so the park shifted its approach from rearing fish to purchasing them from local hatcheries outside the park at a cheaper cost. The hatchery was supervised during the war years by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as a side camp for conscientious objectors. Later, in the 1950s, the Kephart camp was dismantled and the buildings were removed. All that remains of the camp today are boxwoods originally planted around camp buildings, a nonfunctioning stone water fountain, a brick and stone hearth and chimney, and, farther up the trail, at the hatchery area, a cistern-like cement structure.21

In the park’s first master plan, the Oconaluftee Ranger Station was envisioned as the North Carolina park headquarters, and it was to be surrounded by a museum, residential staff buildings, and utility buildings. Consequently, the ranger station was sited at Floyd Bottoms, a large area of flat land where the river broadens and slows at the floor of the valley. This is the site of the nineteenth-century Enloe farm, first occupied by patriarch Abraham and later by his son Wesley. After Wesley’s death, the land was sold to Lon Floyd, and his heirs, also owners of the Mingus Mill property. The Floyds then sold it to the state for the park. By 1938, work began on the ranger station with a Public Works Administration allotment of $18,000. The crew used stone quarried at Ravensford by CCC workers. This same stone was also quarried and transported to Tennessee, where it was used for the park headquarters at Sugarlands. The CCC transported the stone from the quarry and did all the masonry and carpentry for the ranger station. Sources credit two stonemasons for their skilled workmanship on the building: Spanish-born master stonemason Joe Troitino and T. Walter Middleton of Little Canada, North Carolina. Middleton was an enrollee whose skills improved with practice; he once told Ranger Tom Robbins that the east end of the building is rougher than the west one because they constructed the west one second.22 The building, now situated next door to the larger, new Oconaluftee Visitor Center, which opened in 2011, included a public area for visitors seeking information as well as offices for the chief ranger and other park staff. Its design was similar to the Sugarlands headquarters, with native stone facings on exterior walls, a stone fireplace, and a full-length front porch. Though the roof was always intended to be slate, wood shingles were installed for the opening in November 1940 and replaced with slate in 1955. Once the building was complete, the CCC landscaped around it with shrubs, retaining walls, and a parking area. The other planned buildings of the complex were not built at all during the CCC era.23 When they were built later, they were placed elsewhere.

Unfortunately, the Oconaluftee Ranger Station was not complete on September 2, 1940, for the park dedication headlined by President Roosevelt, though the headquarters at Sugarlands was open.24 This event represented the official opening of the national park and recognized the years of effort that park proponents had invested. They had worked tirelessly to sway public opinion about the park spanning two states and then managing all the governmental, legal, and social challenges of transferring hundreds of private farms and logging company holdings to the federal government. Amid this celebration, recognition of the residents who were displaced by the park was also made. Among other local guests, the National Park Service invited two Oconaluftee Valley farmers to attend the ceremony at Newfound Gap; they were Aden Carver and Dock Conner. Also invited were two descendants of William Holland Thomas (his daughter-in-law and granddaughter) in recognition of Thomas’s many efforts to secure the homeland of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.25 After the event, FDR’s party drove along Newfound Gap Road into North Carolina to meet with Cherokee officials. Along the way, his motorcade passed by CCC boys lined up in formation and wearing uniforms in front of their camps’ entrances. One of the leaders of the Italian American company, a First Sergeant Jackson, however, was dressed in an all-black western outfit complete with Stetson hat and cowboy boots. As a newspaper account tells it, the president noticed the man out of uniform and called him over to the limousine, asking, “What in hell are you supposed to be?” The sergeant replied that he was a CCC boy but paused and emphasized the first C for “civilian” in the acronym. This response was met with laughter and acknowledgment. After the exchange, the president gave Johnson a ride to the company’s mess hall, where the head of state joined a group of enrollees for lunch.26

Once the United States entered World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the social and economic purposes of the CCC were replaced by the need for soldiers for the war effort. Consequently, Congress ended funding for the program in the summer of 1942. Most camps closed rather quickly after that. All CCC work in the park stopped August 8, 1942, leaving many projects unfinished, including two bridges across the Oconaluftee River (one at Kephart Prong and the other at Smokemont), as well as utilities, a flume, and additional pools for the fish hatchery. Some of the men who worked in camps remained in the area, even though they were not locals. Tilghman Bass, Shelton Bradsher, Duncan Cox, Jimmy Gaither, Barry Gaither, and First Sergeant Johnson (who married a local woman) stayed in Swain County. Camp physician Dr. Roy Kirchberg went into private practice in Sylva after 1936. Ed Chambers was a CCC boy who joined at age sixteen and worked for two years, and Columbus “Clum” Cardwell, a local, also joined; later both worked for the park service. Clum was an automotive mechanic for many years.27

THE LAST TO LEAVE THE TOWNSHIP

It is difficult to trace how the remaining farm families departed the part of the valley that became the national park in the 1930s and 1940s, but it seems that leaseholders gradually moved on despite their great reluctance to depart. Many made homes in the nearby North Carolina counties. Oconaluftee local Carl Lambert claimed that “the Floyds, Queens, [and] Parks, moved to Virginia. Bradleys, Chambers, and Conners moved to Tennessee. Beck[s] and Conners moved to North Georgia and others to the West Coast.”28 During the CCC era, a handful of people still lived in the park. One resident, Clementine “Clem” Enloe, had a farm on Tight Run. Her husband was “Biney,” a nephew of Wesley Enloe. Biney had died in October 1930, and Clem kept the farm with a lease and took care of one of their younger sons, Birtie, who was deaf and mute and then in his forties. She was known by early rangers to be ornery and resentful of new restrictions on fishing. A wiry, independent woman, she fished every day and would regularly exceed the limit. A photograph of her shows her standing and warily staring at the camera. One hand holds a fishing pole, and in the pocket of the dress she is wearing, the shape of a snuff tin can be discerned. In 1940, at age eighty-five, Clem left her old farm and moved to a nearby asylum because of a heart condition. She died in 1945.29 Other residents included Josh Williamson, who lived at Kephart Prong. He drove a taxi and took schoolchildren living near him down the mountain to Smokemont School. The neighboring Dowdle children were some of his regular riders. Eventually, the Williamson family moved to Whittier. Bert Crisp and his family of boys moved from their Mingus Creek farm to Tow String in the mid-1930s but then bought a farm in Whittier several years later. The Smith family, the Reagan family below Collins Creek, and Wiley Conner and his family were in residence in the 1930s, too. The Reagans had a small kerosene-powered mill for corn during this time. Tow String resident Dan Lambert, then a young boy, recalled that sometimes there would be a kerosene taste to the meal.30

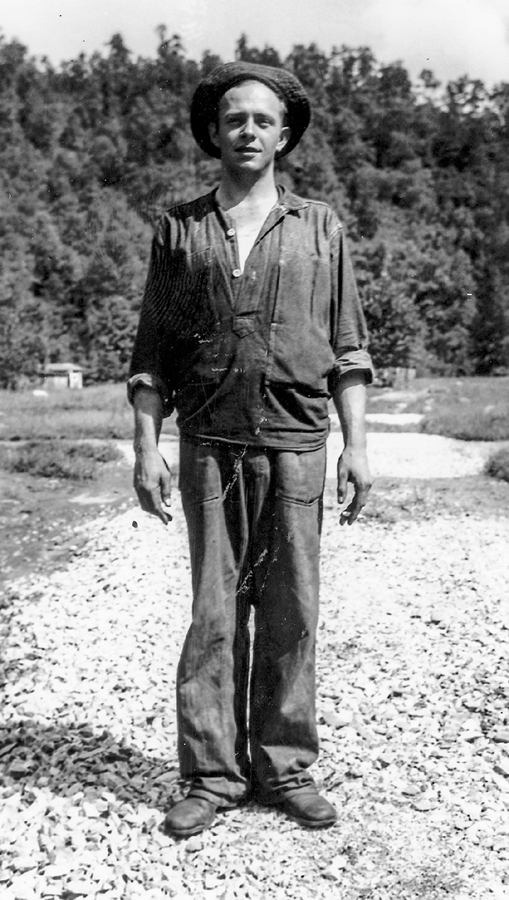

Columbus “Clum” Cardwell in CCC work uniform, 1935.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

Clementine “Clem” Enloe going fishing, 1935–36. Note the snuffbox in her dress pocket.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

The year 1937 marked the moment when significant changes began. Dock Conner’s family at the old Collins farm began moving out of the park at that time. They had bought land in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, long before in 1926, wisely anticipating the need to leave Oconaluftee, presumably fearing changes that the end of logging would bring. Other children of Dock’s as well as a number of in-laws already lived on the Tennessee side of the park. At first, Dock, Charlie, Charlie’s wife, Ella Beck Conner, and their children lived in Gatlinburg. As Gatlinburg grew into a tourist resort, they built a home and moved on to their property in Pigeon Forge. Dock had long been a widower; now that he was older, he moved in with Charlie and Ella, staying with them until his death in 1948.31

Distant cousin Edd Conner also died in 1937 and was at last permanently laid to rest in the white burial suit and walnut casket he had had so meticulously made for this purpose seventeen years earlier. He was seventy-three and buried in the Bryson City Cemetery. Late in the same year, Charles Bascom Queen and his wife, Mary Fisher Queen, moved out of their Smokemont home. They eventually bought “a small farm in the Olivet Community of Jackson County.” Just before, their granddaughter, Agnes, was born in the family home. Agnes was the child of Maisie Queen Young and her husband, Frank.32

In April 1932, the Smokemont church and its 0.77 acres of land were transferred to the State of North Carolina for inclusion in the Smokies. The trustees and deacons were provided $1,100 for the value of the property. After the sale, the church continued to meet and function as the spiritual home of the families still living nearby and as a place of worship for the CCC enrollees. The Queen family had been one of the longtime supporters of the Smokemont Baptist Church. No doubt when they and others moved away, the viability of the congregation’s continuing its weekly services and lease diminished. In 1939, regular services at Smokemont ended, and the park took possession of the church building. At the time, Jesse Lambert was pastor, and he led some forty members to establish Tow String Baptist Church in the Tow String Community two miles south of Smokemont.33 Tow String was and is a pocket of privately deeded land surrounded by Cherokee land; for this reason, even though it is adjacent to the park, it was not acquired by it. Though always a part of the Oconaluftee Valley community, Tow String remained near but not within the national park, and a handful of families lived there. By the way, the origin of the name Tow String is not fully known. Former Oconaluftee park ranger Tom Robbins has suggested that the name comes from the use of flax to make fabric. The raw fiber was soaked in water to separate the tow, “the short, rougher fibers,” from the finer ones. “The finer fibers were used to make linen while the tow is used for rougher materials—tow sacks.”34

Longtime Oconaluftee residents Ben and Emma Conner Fisher were active members when the Smokemont Baptist Church closed. In fact, Emma was a descendant of Samuel Conner, who had been among the church’s founders over a century earlier. In response to the strong ties that the Fishers and other members felt to each other and to the church, Emma organized a group to hold the first church reunion in 1940 by sending postcards out to members to announce the date. She maintained the church’s records and mailed out letters of dismissal from Smokemont as relocating members found and joined other churches. Ben became an employee of the park service, so this couple took it upon themselves to jointly prepare the church for the homecoming revival week and Sunday reunion service every year. Their devotion to this event over the span of decades never flagged. On July 21, 1970, they were working at the church in anticipation of that year’s approaching homecoming. Ben worked outside while Emma cleaned the church windows inside. During a break, Emma brought her husband water for a cool drink, and sadly Ben collapsed from a heart attack and soon died. His funeral was held at the church.35 In time, Jesse Lambert’s son, Dan Lambert, took on the task of being the preacher and organizer for the reunion; as a Tow String resident and pastor of Wright’s Creek Baptist Church in Cherokee, he presided over revivals, weddings, and funerals held at the church. Even later, Raymond Matthews, the pastor of Tow String Church, became the point person for the reunion, though Dan continued to preach well into the twentieth-first century. In 1976, Smokemont Baptist Church was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.36

Young couple outside Smokemont Baptist Church, 1930.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

As World War II approached, was fought, and ended, other icons of the community departed. The commissary in Ravensford, run by Oscar McDonald, closed in 1944. Once the CCC camps there closed, the fields were maintained as open meadow.37 For the first time in many years, they were empty of buildings and, of course, part of the park. In 2004, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians gained ownership of Ravensford in a land swap with the National Park Service and built a school complex there. The descendants of those who lost this land to the park were unhappy about the swap. It represented a broken promise: when they were forced out, they were told the land would forever be a part of the park.38

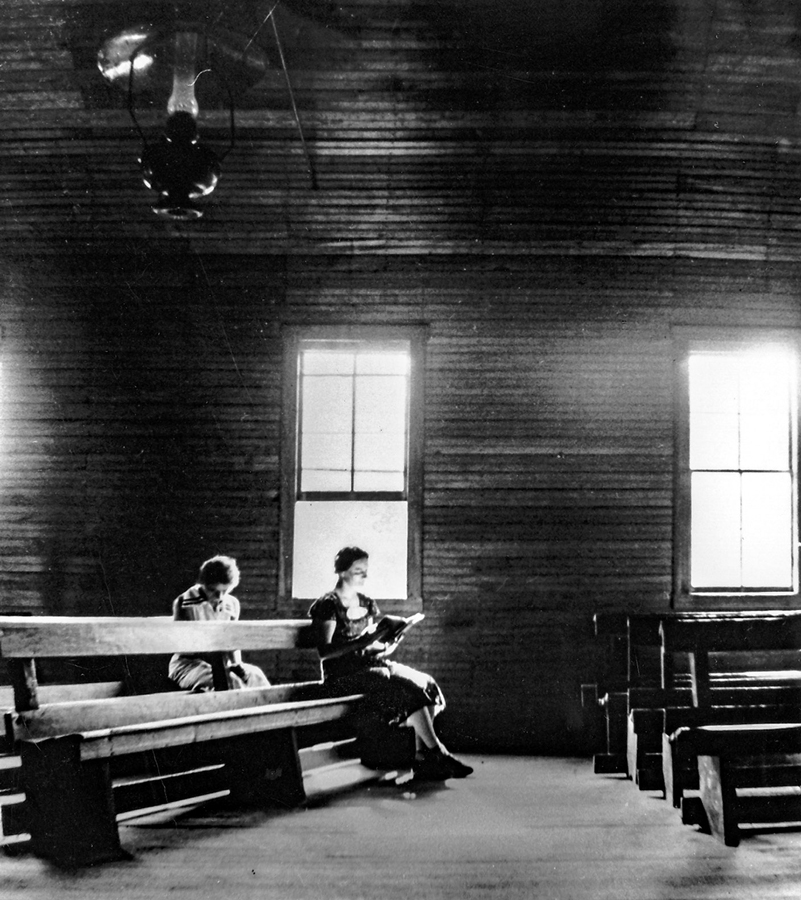

Two women sitting inside Smokemont Baptist Church, 1930.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

A month after the celebration of his 101st birthday, Aden Carver passed away on June 24, 1945. He had been living on his farm just up from Smokemont campground with his son Julius since the park came. When he died, he was the oldest known resident of Swain County. His death is significant because he had played a role in so many of the community’s key events and achievements. In his teens, he helped supply food to the members of the Thomas Legion ensconced at Fort Harry over the mountain ridge. He helped build the second, grand Mingus home and Mingus Mill in the 1870s. After a number of years working as a millwright and carpenter in Tennessee, he returned to help his aging father farm the family land, which he inherited and lived on until his death. He worked for a time in the Smokemont mill during the logging years and with the CCC on the restoration of Mingus Mill in the 1930s. He was a member, deacon, and song leader of Smokemont Baptist Church. With his wife, Martha Roberts, he raised eleven children, including two sets of twins. Recognizing his status as the quintessential mountain farmer, Park Superintendent Blair Ross and other park service employees from the North Carolina side of the park attended his funeral. He was interred at the family plot behind his home. As he had for his mother, Aden carved his own tombstone. The natural upright stone includes a tracing of his granddaughter’s hand at its base reaching up toward a cross. Janice Carver Mooney, who had been the child, later explained that the hand was reaching heavenward toward his eternal home.39

By the time Dan Lambert of Tow String returned from service after World War II, the park, its visitor centers, trails, campgrounds, and picnic areas were open and welcoming. Though a few last lessees held on, their numbers had dwindled. Following other locals, Dan joined the park service. He worked at fire towers and then on road maintenance for a total of thirty-one years, even as he served as pastor of a church in Cherokee. He rose through the ranks and eventually became a foreman with the lofty title of “equipment engineer.”40

Jaheu Conner and his wife, Nellie Bradley Conner, were among the last remaining Oconalufty Township residents. Since logging days, they had run the store at Smokemont, living above it. After the property was sold to the park, they continued to run it with a yearly lease. The store was located near the Smokemont campground and had the first gas pumps on the North Carolina side of the park, so it got steady business, particularly in the summer. Still a general store, it sold “clothing and groceries and whatever you needed, some tools, just more or less a general merchandise store.”41 Because the park did not allow electricity, Jaheu and Nellie used oil lamps for light and block ice for refrigeration. Of course, they knew that their situation at Smokemont was tenuous, with only a yearly lease. So back in the mid-1930s they had bought property in Pigeon Forge adjoining their relatives’. Jaheu was a son of Dock Conner and a brother of Charlie Conner, who had already relocated to Tennessee. A tract of sixty-two acres was put up at auction due to foreclosure, and Jaheu bought it with an $8,000 bid. In 1948, Jaheu supervised the building of a new home on this land while Nellie ran the Smokemont store. When they left Smokemont in February 1949, Jaheu was sixty, and Nellie was in her early fifties. They focused on farming their Tennessee land for a few years until Tennessee routed a new four-lane highway across it; then managing the livestock and fields across the road became difficult. So they sold the land across the road at auction in thirty-six small lots, beginning the tourist industry along Highway 321. As with both their Oconaluftee homes (at Collins Creek, and later at Smokemont), they were situated on the main road to the mountains, a road many tourists traveled. This family no doubt became one of the luckier ones displaced by the park.42

Conner’s General Store at Smokemont, 1921.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, TOWNSEND, TENN.

Once the Smokemont church and store closed, Oconalufty Township was all park. The old community was no more. In the way that people value things once they are gone, the park created a pioneer farmstead next to the ranger station, on the old Enloe farm, also known as Floyd Bottoms. It displays the way of life of late nineteenth-century farm families. In 1994, the farmstead was renamed as the Mountain Farm Museum “to better convey to visitors the open-air museum aspect of the collection of buildings.”43 This museum includes authentic farm buildings as well as a heritage garden and open fields. Though a number of the buildings were relocated from other parts of the park, the massive barn is original to the property. It is a drover’s barn, with a long, narrow central passageway that goes straight through. Stalls for horses and other livestock open from the center on either side. The hayloft above reveals the barn’s size; a 2,500-square-foot home could fit inside it.44 This museum provides the best example of how the prosperous and longtime mountain families lived. It also provides a poignant testimony to the history of the valley at the central southern North Carolina park entrance. That the museum is so close to Cherokee, the home of the Eastern Band, is fitting. The histories of the Oconaluftee mountain community and that of the Cherokees who resisted removal and remained on their ancestral lands have been deeply intertwined since the early 1800s.

LESSONS OF ENDURANCE

As logging declined and the park became a reality, the Eastern Band’s position in the valley changed. As early as 1914, with the first Cherokee Indian Fair in October, it began to develop a tourism business that would serve as an ongoing economic strategy to sustain its members. By the 1930s, the craft business was established. Further, by 1934 and the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act by the federal government and its approval by the EBCI—the part of the New Deal that aided Native Americans—the looming threat of allotment ended. In addition the act allowed for the establishment of tribal governments, protected and promoted Native American culture, and supported schools and business endeavors, all much needed provisions to help the band’s political stability and well-being. During the same decade, the tribal council successfully negotiated land sales to the federal government for the southern segment of the Blue Ridge Parkway that would connect the park-as-highway with the Great Smoky Mountains. The council resisted early proposals of a parkway route that would disrupt the community and succeeded in gaining agreement on a favorable ridge route, with generous compensation, that skirted Cherokee farms and still provided tourists access to the park and the reservation, along with its growing attractions. Parkway construction on this segment was underway by 1940 when the park was dedicated. In the next ten years, the first Eastern Band–owned tourist complex would open at the Boundary Tree site and productions of the summertime outdoor drama Unto These Hills began.45 Like all Native American communities, the Qualla Boundary continued to face citizenship, property, economic, health, and educational challenges, but by the 1930s a number of protections against future threats were firmly in place.

Some see justice in the slow unfolding of events that positioned the Qualla Boundary as a unique feature of western Carolina to be acknowledged, appreciated, and exploited for regional economic development when once the Lufty Cherokees had been pushed off their land and oppressed by white families who were, in turn, removed. Perhaps. Another idea is that the trajectories of the Eastern Band and the Oconalufty Township suggest multiple forms of resilience and strategies of adaptation when crises and change arrived, all of which are instructive. The Eastern Band endured for many reasons. Notably, the people were resourceful individually and collectively. They had a durable identity as a community while they accepted necessary internal changes. They chose capable, far-sighted, and committed leaders who appear to have learned painful lessons from the deerskin trade that ensnared them to capitalism and weakened their agency through debt. Often, they responded in time to outside threats with a unified approach. The assistance of powerful external advisers and government officials saved the day at several critical junctures. Sometimes the Cherokees were a bit lucky with timing, though they also absorbed shocks and blows that had serious impacts.

The township families were also resourceful and had a strong community spirit. Maybe because they saw themselves as part of the dominant culture of North Carolina and the United States, they were not motivated in the same way as the Cherokees to act in a unified fashion against trends that would eventually overwhelm their lives in the valley. They likely did not expect that they would become vulnerable because they perceived their status as top tier for too long. Though race was always a factor, and they had that going for them, it was not the only one. Money was and had always been. Without recognizing the threat to their community, they embraced commercial logging, which exposed them to speculators, upheaval, degradation, fire, and outside interest. If the logging companies were run by elite capitalists pursuing profits, the park proponents were a political power elite, both regional and national, seeking economic development through tourism (apparently as much as recreational options, resource restoration, and wilderness protection). Township residents were subjugated—twice—by those who wanted their land and its resources for what it could do for people outside the valley. And yet some folks still found ways to adapt and hang on. They did so alone, not collectively. They did not organize as a community to push back, which isolated the few who did resist, like George Beck and Clem Enloe, and put them to a disadvantage. But even amid their dispossession, some families got on. The Conner households who moved to Tennessee likely were the most foresighted and strategic (but then they had the resources to be so).

I am reminded of the Cherokees’ precolonial identity as “the Principal People.” They were the dominant indigenous group in the Southeast. That identity may not have served the Cherokees well once the Europeans arrived. Though the white valley township families did not apply such an idea to themselves, as far as I am aware, I think they may have conceived of themselves in a similar way—somewhat privileged. Those with good land occupied a sweet spot. I think this not because of the land owners’ arrogance; certainly arrogance is not expressed in the records. But we humans are susceptible to self-absorption. Similar to the way in which humans are all mostly anthropocentric, we often believe in our own and our own ethnic group’s edge, superiority, if not hegemony. This belief functions as self-confidence. Of course, the trouble is that it can be self-deceptive—as well as cruel, unfounded, limited, and socially counterproductive. Leaving aside the other flaws, though they are equally important, the problem with too much self-confidence is that it can blind one to events beyond one’s own control, which may make it less likely to notice warnings and dangers in time to avoid them. Survival, then, may be linked to humility, even empathy.

That said, the valley should be remembered for important instances of cooperation and civility between the Cherokees and the white mountain farm families during the nineteenth century. They shared food when crops failed, provided medical help during periods of widespread disease, served together in the Thomas Legion, and undertook community projects such as roads and mills. The legacy of African Americans in the valley is more difficult to generalize about; so little is really known about this topic. Clearly, they provided labor for all sorts of efforts. The ethnic groups may not have been or behaved like kin, friend, or allies at every turn, but they managed a neighborliness that was consequential and remains inspirational. More investigation, most properly conducted by descendants, into the ways that peoples’ personal lives straddled the ethnicities in the valley would yield new insights into questions of mutual esteem and daily ambiance during the nineteenth, twentieth, and current centuries. Given the scope of my work, all I can do now is point out this enticing research direction for others to explore.

The three ethnic groups—Cherokees, whites, and African Americans—continuously faced tests and opportunities in regard to the region, state, nation, and even other countries. During no period was the valley beyond the reach of outside forces. Here ethnic groups’ circumstances differed considerably most of the time. Because of their different identities and status, their options were distinct as were their degrees of exposure and vulnerability. What they shared were resourcefulness and resilience when it came to major disruptions and long-term trends. I find the ability of all the valley’s residents to respond to their crises heartening and instructive. Understanding that their challenges will not be those of today’s places or societies, I view their stories as exemplary.