CHAPTER 1

Humoral/Environmental Theories and the Chain of Being

Current arenas in the ongoing conflict over the relationship between nature and culture are easy to locate. The terms of debate are familiar because there is a general consensus about the relevant theories and evidence to be discussed. The semantic and lexical impact of evolutionism is strong and provides the needed signposts. But before evolutionism, comparable discussions of the human condition employed different terminologies and styles of argument.

The pre-evolutionary literature dealing with “human nature” and its social, political, ethical, and theological consequences spans the whole Western tradition. Nevertheless, it is difficult to find contemporary analytical discussions that focus directly on these biological issues because of the tendency to dematerialize the material/biological dimensions of important philosophical works and to forget how concerned major thinkers have been with exceedingly mundane problems. The history of biological and medical thought, for example, is often treated separately from the history of Western philosophy.1

Naturalistic Views of Society

My choice of materials is guided by some specific assumptions about the necessary contents of any naturalistic view of society, evolutionary or not. Any such view provides answers to the following questions:

1. What exists in the world and how is it organized?

2. How much of the outside world is found inside of human beings?

3. Are humans an entirely special form of creation, or are we constituted of the same matter as all the other things in the cosmos, differing from other life forms only in organization? If it is assumed that humans are composed of the same matter as everything else in the world, a fourth question then arises:

4. How does what is outside in the world get inside of human beings? This question centers on the mixed sources of heredity and environment as they influence human structure and behavior.

5. Is matter from the outside world altered in any way when it is found inside of human beings? This question involves a complex of ideas about the transformation of the primary constituting properties of matter into blood, bone, and tissue as manifested in a human body.

The final question is complexly theological and theoretical:

6. What is left of a human being if all matter from the outside world is removed? Centering on the host of issues about the mind and the soul, this question includes others about the organizational principles that give humans particular characteristics and whether or not these organizational principles are intrinsic aspects of physical matter.

A naturalistic view of society thus provides an explanation of the origin, structure, and behavior of living things and then places humans within that context. It does so against the backdrop of a theory of the structure and operation of the material universe. Darwin’s theory of the origin of species and the descent of humans is one such theory.

Before Darwin, a combination of ideas about the material structure of the universe, its relation to the structure and behavior of human beings, and the origin of the entire system dominated Western thought from the fifth century B.C. onward. This tradition includes theories about the physical elements of the universe, their effect on the humoral constitution of human beings, and the origins of the separate categories of living things (i.e., the “origin of species”).

A caveat is needed. Over two millennia of Western thought are compressed into a simple mold here. This necessary simplification makes it difficult to see that the attractiveness of these ideas lay precisely in their ability to organize the complex world of experience into intelligible categories for thought and action. A much more elaborate discussion of these issues is available in Ernst Mayr’s Growth of Biological Thought (1982).

Humoral/Environmental Theories

Humoral/environmental theories form an intriguing and complex explanatory system linking the universe, the earth, humans (as a group and as individuals), and even historical events into a single overall scheme. Simultaneously they provide practical guidelines for conduct. These systems are based on meticulous, consistent observations of the physical, biological, and cultural worlds. They assert that the world is orderly and that it can be studied by systematic means.

The fundamental materialism of this tradition makes a clear appearance in the great medical texts of antiquity. Soon thereafter the separation between material and moral causes of temperament and disease ramifies into a fully developed empirical tradition (La***m Entalgo 1961).

The humoral/environmental theories are always emphatically non-evolutionary. They offer no dynamic, material explanation of the origins of the categories of living things or any continuing process by which new categories come into being. Early on, the species are the work of a variety of gods or processes of interbreeding; later they are produced by the God of Genesis.

The power of these humoral/environmental theories is amply demonstrated by their durability. When in the eighteenth century the Spanish medical thinker Martín Martínez made a thorough critique and attempted renewal of medicine, he expressed his ideas in two volumes of dialogues between a chemist, a follower of Hippocrates, and a follower of Galen. Knowledge of Hippocratic and Galenic texts makes most of Martínez’ arguments—and those of his English, French, German, and Italian colleagues—quite intelligible despite the many centuries and scientific discoveries that separate them. Qualities, elements, and humors were as fundamental to eighteenth-century thought as they were in antiquity; these ideas persisted through the Arabic renderings of Galen and other classical writers until the originals were rediscovered during the Renaissance.

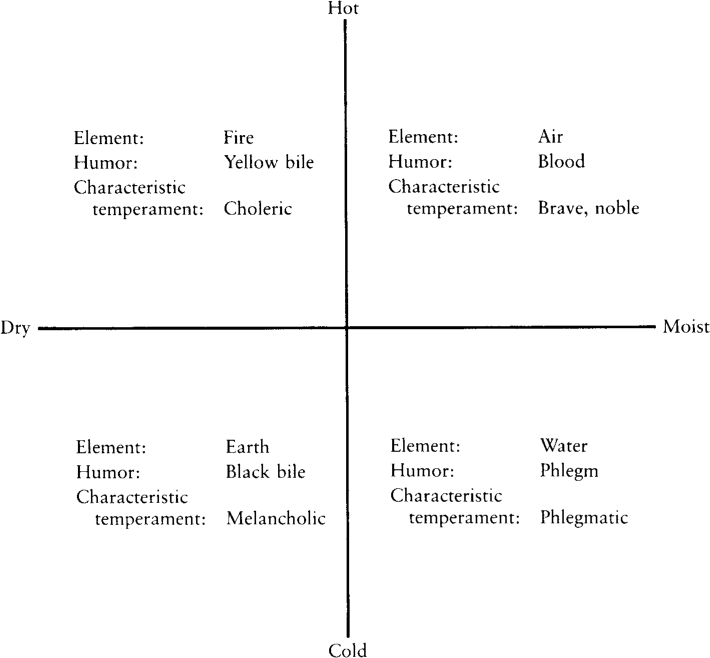

The basic structure of ideas consists of sets of dual oppositions. Figure 1 charts their interrelationships. According to their structure of ideas, the material world is divided into primary qualities, elements, and humors. The primary qualities are not themselves manifested directly in matter; rather they are the fundamental characteristics that cause the various compositions of matter in the perceivable world. These qualities are arrayed as two sets of dual oppositions: hot/cold and dry/moist. Everything in the world is a material manifestation of combinations of these primary qualities. The basic elements of perceivable matter—earth, air, fire, and water—result from the differing combinations of the primary qualities. Dry and cold yields earth; moist and cold, water; moist and hot, air; and hot and dry, fire. All things in the material universe are made up of varying combinations of these four elements, which in turn are combinations of the primary qualities.

When these four elements combine to form organic beings, they are converted from elements into humors. These substances that constitute organic beings retain the properties of the elements that give rise to them. In a living body, fire yields yellow bile; air becomes blood; earth becomes black bile; and water yields phlegm. All beings are made up of particular combinations of these four humors. Every species and individual has its particular humoral makeup.

Each of the humors has a direct behavioral counterpart in this complex cultural system. Personal characteristics are explained by reference to the predominance of certain humors and the actions of these humors are explained by their elemental makeup. Direct material causation of physical and behavioral states is thus assumed. The predominance of yellow bile (fire, hot and dry) leads to choleric behavior. The prevalence of blood (air, hot and moist) yields militancy and courage. When phlegm controls (water, moist and cold), passivity prevails; and the dominance of black bile (earth, cold and dry) causes melancholy. Many forces influence the balance of the humors, genealogy and the environment being the primary ones.

FIGURE 1 Elements, humors, and characteristic temperaments associated with combinations of the four qualities

In antiquity the study of the humors and their causes and effects (termed physiologia physis) embraced the double meaning of “Nature” and the multiple “nature” of things. Nature and the multiple natures were assumed to have a logos, a harmonic reasonableness in them. Human logos was rational knowledge, among other things. Thus human logos attempted to understand and control the logos of Nature and of natures. This activity was called physiologia—human logos seeking to understand and manage the logos of the physis. And this activity was based on an understanding of the elements and the humors.

To most Westerners, these concepts are vaguely familiar. Even though the language of biles and humors has become obsolete or at least archaic, the complex metaphorical relationships between hot and dry: fire and anger; hot and moist: blood and life; cold and moist: water and peace; and cold and dry: earth and melancholy remain intelligible. Indeed, they are found in ordinary speech to a surprising extent. Powerful literary associations and present-day assumptions about racial characters are based on them.

A basic characteristic of the humoral/environmental theory is its complex hierarchical quality. The universe is constructed of combined primary qualities, physically manifested as elements. All parts of the universe must have these constituents; they must be, in a sense, microcosms of the macrocosm. Differences between distinguishable physical things arise from the quantitative differences in the combinations of the elements of which they are formed. In the organic world the elements are manifested as humors, and the humors, depending on their quality and quantitative mixtures, determine behavior.

From top to bottom and from outside to inside, the universe is made up of varying combinations of four primary qualities. The differences between things reflect only the differing quantitative mixtures of these qualities in the form of elements and humors.

The Environmental and Genealogical Principles

Explanation in this system is basically a matter of accounting for the composition of a particular thing, be it a planet, a rock, a human, a disease, or an emotion. The accounting can be done in two related ways. First, the physical conditions that prevailed at the place and time an entity originated can be used to explain its character—that is, direct environmental causation. For convenience I will call it the “environmental principle” of causation.

Alternatively, the character of an entity can be explained as an inheritance from its progenitors, whose initial traits were fixed through the operation of the environmental principle or by some act of special creation. I will call this the “genealogical principle” of causation. Together these two causal principles play a major role in the social, political, and moral extrapolations based on this theory.

Humoral/Environmental Explanations

These humoral/environmental views are exceedingly adaptable. Major Western developments in cosmology, geography, geology, biology, and medicine reflected the playing out of these basic doctrines for well over two thousand years. Since, in this view, the whole cosmos operated according to material principles that were everywhere the same, certain kinds of scientific research were given major encouragement.

At the same time, these views dictated the terms of major theological questions: What kind of creator would originate such a system and under what circumstances? Could there be anything more to a human being than the combination of four humors? To these questions there are innumerable answers.2

Humoral/environmental theories state that the universe is made up of qualities manifested as elements. All four of these elements, transformed into humors, are present in organic benings. Both the environmental principle (immediate physical causation) and the genealogical principle (inherited humoral constitution) are used to explain the way the outside world comes to be part of human beings. Persons are as they are because of where they were born or because of the characters of their parents.

An additional theory is needed to explain how the humors are generated within each human being, and medical history books review a festival of them. Perhaps the most popular view was that the primary humor is the blood: it is the blood that passes on from parent to child, providing the genealogical connection. Accordingly, the blood must somehow contain the other humors or assist in their creation out of elements the person incorporates from the environment. Each generation reproduces itself by means of the blood, which then reproduces the other humors.

Each human being has individual characteristics because of the combination of the humors within. This combination is given by the genealogical principle but is strongly affected by the immediate physical environment, as the subsequent discussion of Hippocrates will show. This dual action of the environmental and genealogical principles neatly sets the foundations of the nature/nurture debate still with us today.

How the parents come to have the particular combination of humors that characterizes them is partly a matter of the blood they received from their parents and partly a matter of their environments. Theorists weight these two factors differently, and arguments over this weighting are a constant feature of these debates. Except in a few extreme cases, so-called hereditarians and environmentalists are separated mainly by a matter of emphasis, a point that deserves more attention than it has received.

Logically implied in this approach to causation is the need for an original creation. The genealogies of entities have to originate somewhere at some time. If one wants to know why humans or for that matter any species has a particular set of characteristics, it is necessary to posit an original moment of creation when those features either first arose directly out of a specific environment or were simply created. Thereafter all history is simply the playing out of combined environmental and genealogical influences as they operate on the original template (constitution, “nature”).

The close but ambivalent relationship between the environment and human characteristics is strongly emphasized in this view. Since humans are composed of humors derived from the same elements that make up the surrounding physical/biological universe, humans are easily affected by environmental factors. As the texts of Hippocrates, Galen, and other early medical theorists show, a major part of medical practice had to do with the diagnosis of basic human constitutions and of environmental effects on them, and the elaboration of treatments that altered the internal composition of humors by applications of varying combinations of the elements to the body, either internally or externally.

While the environment leaves it stamp on the individual, the genealogical principle also insists that some of what an individual is comes from the parents, the parents’ parents, and so on. Thus some aspects of the individual resist the influence of the local environment. People are as they are because of their ancestors; they “breed true.”

This ambivalence between direct environmental causation—a view that is completely consistent with humoral/environmental theory—and genealogical causation, which is much more difficult to assimilate into the theory, is a basic feature of thought in this tradition. Genealogical causation is partly consistent with the theory in that the physical substance of an offspring is directly derived from that of the parent. The massive incorporation of the environment in the form of food and other local influences, however, makes the autonomy of these genealogically transmitted substances hard to maintain theoretically without a well-developed material explanation of heredity. We only now have such an explanation with modern genetics. In most versions of this idea, the genealogical principle is converted quickly into a kind of nonmaterial identity transmitted in the blood.

Given this ambivalence, the central analytical task involved in the application of the humoral/environmental theory to humans is to decide how much of the makeup of a particular person or group of people is caused by the immediate physical environment and how much is caused by the genealogical principle. To the extent that the local environment is a determining factor, a doctor or a ruler can alter the people by altering the environment (insofar as it is possible to do so) or can move the people to a more suitable location.

To the extent that the genealogical principle is a determining factor, a leader can only adjust institutions to suit the characteristics of the people, move them on an environment in which their genealogical traits in combination with the local environment will produce a desired result, or breed them to alter their traits. This is the nature/nurture argument in its old suit of clothes. Current nature/nurture debates make it clear that little has been added to this view since Hippocrates’ time.

The complexity and coherence of the humoral/environmental theory are intriguing. All things—the universe, the planets, animals, humans, individuals—are characterized by varieties of equilibria of their qualities, elements, and humors. The states of sickness and health in individuals vary because the equilibria of their humors vary. Medical treatment acts to restore balance. Individuals differ from one another because of their different personal equilibria. Sexes, races, and species differ for the same reasons that the seasons, periods of life, and periods of history differ. Groups of people in the same places are similar because of their environmentally caused similar humoral makeups. Members of the same families are similar because of their genealogically caused similar humoral constitutions. Thus similarities and differences between people are accommodated and explained by the same small set of principles. Evil, illness, aggression, bad government, and other problems are caused by disequilibria of the elements and humors. Social justice and peace are accomplished by a process of equilibration.

The humoral/environmental theory is thus a very broad theoretical framework for the explanation of the material, organic, and human world. While it cannot account for the initial creation of the categories of entities in the world, it does explain the development and current operation of the world and serves as a guide to conduct. It is thus a theory of great generality and utility.

“Airs, Waters, and Places”

A review of Hippocrates’ “Airs, Waters, and Places” (1886) indicates how the theory was actually used as an explanatory model for analyzing human behavior and as a guide to its alteration. Whether or not Hippocrates was a real person is the subject of learned debate. All that can be said with certainty is that there is a collection of medical texts dating from between 460 and 377 b.c. and that these texts are conventionally grouped under Hippocrates’ name.

The famous treatise “Airs, Waters, and Places” is a combined medical handbook and theory of human history based on the analysis of the particular interactions between the elements and their humoral consequences in different environments. It begins with a typology of cities according to the kinds of airs that influence them. Cities exposed to hot winds typically give rise to humid diseases, while those exposed to cold winds produce hard and bilious diseases. The cities in which the west wind predominates combine hot and cold in an unhealthy way that leads to both bilious and febrile disease. Only cities exposed to both hot and cold winds are truly healthy human environments.

A similar typology of waters is elaborated. Marshy areas give rise to bilious diseases. Areas of rock springs cause diseases of hardness. Waters from elevated ground are best, as are waters from the east; those from the west are not bad; those from the north are poor; and waters from the south are extremely unhealthy. Water treatments are recommended for diseases caused by waters. Rainwater, for example, is used to counteract the influence of snow and ice. The treatise also argues that when unlike waters mix, the kinds of airs present will determine which water will prevail. The same system is used to deal with the four seasons. Each season is seen as a combination of temperatures, humidity, and wind—as the working out of the primary qualities in various combinations.

The text then compares Asia with the Mediterranean area in terms of the predominance of various airs and waters and their impact on the human inhabitants. In an overview the author argues that climates that experience great and rapid change give rise to the greatest amount of human diversity, while climates of little change promote human homogeneity.

Up to this point the environmental principle is absolutely paramount. Everything is directly caused by the action of immediate environmental features. But then the text breaks into a different line of argument. The genealogical principle appears and comes into conflict with the environmental principle. In Hippocrates’ view, for example, the seasons are modifications of the “natural frame” of the population:

… with regard to the country itself, matters are the same there as among all other men; for where the seasons undergo the greatest and most rapid changes, there the country is the wildest and most unequal; and you will find the greatest variety of mountains, forests, plains, and meadows; but where the seasons do not change much there the country is the most even; and, if one will consider it, so is it also with regard to the inhabitants; for the nature of some is like to a country covered with trees and well watered; of some, to a thin soil deficient in water; of others, to fenny and marshy places; and of some again, to a plain of bare and parched land. For the seasons which modify their natural frame of body are varied, and the greater the varieties of them the greater also will be the differences of their shapes. [Hippocrates 1886:170–71; emphasis mine]

Having thus raised the possibility of divergence between the local environment and the genealogical principle, the text explores the mechanism by which environmentally caused factors could become part of the “natural frame” in a way that was not definitively challenged until Gregor Mendel’s work gained full acceptance.

I will pass over the smaller differences among the nations, but will now treat of such as are great either from nature, or custom; and first, concerning the Macrocephali. There is no other race of men which have heads in the least resembling theirs. At first, usage was the principal cause of the length of their head, but now nature cooperates with usage. They think those most noble who have the longest heads. It is thus with regard to the usage: immediately after the child is born, and while its head is still tender, they fashion it with their hands, and constrain it to assume a lengthened shape by applying bandages and other suitable contrivances whereby the spherical form of the head is destroyed, and it is made to increase in length. Thus, at first, usage operated, so that this constitution was the result of force: but, in the course of time, it was formed naturally; so that usage had nothing to do with it; for the semen comes from all parts of the body, sound from the sound parts, and unhealthy from the unhealthy parts. If, then, children with bald heads are born to parents with bald heads; and children with blue eyes to parents who have blue eyes; and if the children of parents having distorted eyes squint also for the most part; and if the same may be said of other forms of the body, what is to prevent it from happening that a child with a long head should be produced by a parent having a long head? [P. 171; emphases mine]

Humans can be changed by both nature and culture, all within the overall materialism of the humoral/environmental theory. Hippocrates asserts that semen comes from all parts of the body. By this assumption, it is then possible to state that the condition of any part of the body will be reflected in the humoral makeup of the semen that emanates from the part. This makeup, in turn, will be passed on to the next generation in the form of a permanent alteration of the humoral balance, turning cultural practice into a natural feature of a particular group of people.

This is as clear a statement as can be found of the explanation of the path by which external environmental influences become part of the constitutions of individuals. This argument is of crucial importance to later theories regarding the differentiation of races, nations, and constitutional types.

Later in his text Hippocrates shows the way this materialist theory may be reconciled with the existence of a creator:

… there are many eunuchs among the Scythians, who perform female work and speak like women. Such persons are called effeminates. The inhabitants of the country attribute the cause of their impotence to a god, and venerate and worship such persons, every one dreading that like may befall himself; but to me it appears that such affections are just as much divine as all others are, and that no one disease is either more divine or more human than another, but that all are alike divine, for that each has its own nature, and that no one arises without a natural cause. [P. 178]

The natural and the divine explanations are compatible because deities created nature and thereafter it runs according to the principles set in motion upon its creation.

Toward the end of the essay Hippocrates turns to a more detailed analysis of character differences within the Mediterranean world. He argues that in high, varied, well-watered places, people are enterprising and warlike, while in low and ill-ventilated places they are fleshy, dark, and bilious. In high, flat, well-watered places, people are large and gentle, and in high, dry places, people are hard, blond, and haughty. Perhaps the most surprising thing about this last set of observations is how closely they conform to current ethnic stereotypes about regions within modern nation-states and about differences in national character.

These are the basics of the humoral/environmental theory. A complex, tiered system of thought that is immensely adaptable as an explanatory and classificatory framework, it provides the foundation for most of the arguments (and their internal contradictions) regarding relations between nature and culture before and, I believe, after Darwin.

Natural Categories and the Chain of Being

Humoral/environmental theories cannot account unaided for the creation of the categories of entities in the material world. Yet the observable world is filled with highly organized, diverse entities. Each seems to have a “nature”; each represents a species with characteristic structures and habits. Together these species form a reasonably harmonious whole. Why there are many varieties of entities, how they are organized, how they came into existence, the initial source of each, and the degree to which the set of species is complete or in process (progressive or degenerative) are fundamental questions left unanswered by humoral/environmental theories. The answers given to these questions are numerous, but they share certain basic features.

In the span of time separating Hippocrates from Darwin, humoral/environmental theories were associated with various theories of creation and order. Some of the pre-Christian views attribute the categories and order of the material world to the action of a multiplicity of gods. Other conceptions center on single universal creative forces. The most influential view arose from Judeo-Christian thought, in which the God of Genesis became the source of the categories and structure of the material universe.

God creates the natural order. From the initial chaos God orders matter into the elements and then, one by one, fashions all species out of these elements. Further, God creates all beings in a definite system of interrelationship, with humans at the pinnacle. Once this creation is complete, the work is perfect and no further creation is possible. The orderliness, the marvelous structure of even the simplest being, and the complex relations among species all celebrate the divine plan.

The structure of this set of ideas was superbly analyzed decades ago by Arthur Lovejoy in The Great Chain of Being ([1936] 1976). This book remains the fundamental work on the subject. Lovejoy’s exposition begins with the analysis of a fundamental tension in Plato’s thought between other-worldliness and this-worldliness. By “otherworldliness” Lovejoy means not a belief in an afterlife but rather

the belief that both the genuinely ‘real’ and the truly good are radically antithetic in their essential characteristics to anything to be found in man’s natural life, in the ordinary course of human experience, however normal, however intelligent, and however fortunate… the human will, as conceived by the other-worldly philosophers, not only seeks but is capable of finding some final, fixed, immutable, intrinsic, perfectly satisfying good.… Not, however, in this world… but only in a ‘higher’ realm of being differing in its essential nature, and not merely in degree and detail, from the lower. [Lovejoy 1976:25–26]

This higher realm is the world in which the multiplicity of eternal Ideas resides, ideas of which the things of the natural world are but imperfectly realized copies. Lovejoy goes on to show the basic contradiction between devaluing the natural world and using it as an empirical source for the formulation of the eternal Ideas.

All categories of things in the natural world are imperfect manifestations of perfect and eternal Ideas, but these Ideas are not randomly organized. They are ordered in turn by an “Idea of the Idea,” generally rendered by Plato and eventually by Christian theologians as the “Idea of the Good.” Lovejoy handles it deftly:

… it is… the most indubitable of all realities… it is an Idea or essence… in distinction from the particular and changing existences which in varying degrees participate in its nature; and… it therefore has the properties common to all the Ideas, of which the most fundamental are eternity and immutability… it is the polar opposite to ‘this’ world… its true nature is therefore ineffable in the forms of ordinary speech… the Form of the Good is the universal object of desire. [Pp. 40–41; emphasis removed]

If this idea is accepted, then, as Lovejoy points out, two problems are left unsolved. First, it is not clear why the imperfect natural world should exist at all. And second, if the natural world must exist, what determines how many and what types of things must make it up? The answers to these questions set the relevant point of comparison between pre-evolutionary and evolutionary views of the organic world.

To explain why the natural world must exist, theologians argued that the perfectly good cannot envy anything not part of itself.

Its reality could be no impediment to the reality… of beings other than it alike in existence and in kind and in excellence; on the contrary, unless it were somehow productive of them, it would lack a positive element of perfection, would not be so complete as its very definition implies that it is.… The concept of Self-Sufficing Perfection, by a bold logical inversion, was… converted into the concept of a Self-Transcending Fecundity. [P. 49]

Once this idea is accepted, the question regarding the number of things the world must contain is easily answered. Since the perfectly good could not envy the existence of anything, the world must contain absolutely all possible kinds of things. The world must be completely filled with all the possible natural categories of things. This concept Lovejoy christened the “principle of plenitude.”

And once the principle of plenitude is accepted, the question of the organization of things in this world is also easily resolved. Since the perfectly good is the universal object of desire, and the world of nature is an imperfect copy of it, then all things in the world are arrayed in a hierarchy from the lowest and most distant from the perfectly good to that which is closest to it. In addition, the principle of plenitude requires that there be no gaps in the hierarchy from the lowest to the highest, since the world would thus have less in it than it could have. This hierarchy of categories of things, animate and inanimate, is what came to be known as the “chain of being.”

The humoral/environmental theories provide explanations about the way entities in the material world behave through analysis of their material constitutions. On this level the humoral/environmental explanation is consistently materialist, since the same principles are applied to molten lava and epileptic seizures. But the humoral/environmental theory cannot explain the existence of the categories of things in the world or the origin of their interrelationships. Each kind of stone, plant, animal, air, water, human, disease has its source in principles external to the humoral/environmental view. The source is the eternal Ideas of which the things of the world are only manifestations. Only when humoral/environmental theories are armed with this conception can they become a global explanatory framework.

Let us return for a moment to the contrast between the genealogical and environmental principles. At first it appears that humoral/environmental theories rest primarily on the environmental principle, but it quickly becomes apparent that the genealogical principle is equally important, because only through genealogy can the categories of entities in the world and their interrelationships be explained.

As a result, humoral/environmental theories are always riven by a conflict between the environmental and the genealogical principle. The ambivalence can be seen in Hippocrates’ discussion of the long-headed Macrocephali and in his concept of the “natural frame” that is resistant to environmental influences.

The essences of things, the categories of the natural world, are given by the eternal Ideas. They pass from generation to generation by the genealogical principle. Their transmutations occur only as the result of the action of humoral/environmental principles, and these transmutational principles themselves are ultimately derived from eternal Ideas.

The conflict between the necessary genealogical principle and the primarily environmental bias of the humoral/environmental explanations can never be resolved. The nature/nurture debate is an intrinsic part of this view. It is not, however, intrinsic to modern evolutionary biology, and the persistence of the nature/nurture debate up to the present suggests just how powerful the hold of the ancient humoral/environmental world view still is.