CHAPTER 3

Humoral Politics: Races, Constitutional Types, and Ethnic and National Characters

Nowhere is the absence of a full-scale Darwinian revolution more apparent than in the literature on race, ethnic and national characters, and constitutional types. Post-Darwinian works in this area are a direct continuation of the pre-Darwinian tradition. With the exception of some stray evolutionary terminology, many contemporary works are indistinguishable from their ancestors. This is a case of descent without modification.

In sheer bulk, Western ideas about the differences between races, nations, and constitutional types and their relationship to differing environments have probably constituted the dominant use of humoral/environmental ideas. The number of tracts written on these subjects over the span of European history defies cataloguing. Nor are these the concerns of some restricted class of intellectuals. We know from both current experience and the historical record that all classes of people from all walks of life use racial, ethnic, and national character ideas and constitutional typologies to explain the ways they behave, the ways other people behave, and why some groups are seemingly inferior or superior to others. Anthropologists place these ideas at the very center of the Western explanations of group similarities and differences.

The Hippocratic Tradition

Toward the end of his discourse on airs, waters, and places, Hippocrates explains the differences between racial groups as the result of humoral/environmental factors. Comparing Asia and Europe, he stresses how little they resemble each other physically. He then says:

… Asia differs very much from Europe as to the nature of all things, both with regard to the productions of the earth and the inhabitants, for everything is produced much more beautiful and large in Asia; the country is milder, and the dispositions of the inhabitants also are more gentle and affectionate. The cause of this is the temperature of the seasons, because it lies in the middle of the risings of the sun towards the east, and removed from the cold (and heat), for nothing tends to growth and mildness so much as when the climate has no predominant quality, but a general equality of temperature prevails… the inhabitants too, are well fed, most beautiful in shape, of large stature, and differ little from one another either as to figure or size; and the country itself, both as regards its constitution and mildness of the seasons, may be said to bear a close resemblance to the spring. Manly courage, endurance of suffering, laborious enterprise, and high spirit, could not be produced in such a state of things either among the native inhabitants or those of a different country, for there pleasure necessarily reigns. [Hippocrates 1886:169–70]

In his often cited discussion of the Macrocephali he stressed the physical differences that distinguish these people from other races. The cause is environmental, now in a special sense. The Macrocephali deformed their heads environmentally (that is, by custom), but eventually the deformity came to be inherited. In this view, culture is an effective force in shaping human bodies because it operates by physical means to alter the humoral balance.

This idea introduces an ambiguity into his explanatory strategy. Environmental factors may bring about physical changes in humans either independently or through the effects of cultural practices. The problem, then, is to know when the cause of a physical characteristic is cultural and when it is not. In the case of the Macrocephali, he feels confident of the cause because their head shape is such an oddity.

But how could this approach help one to distinguish between the “natural frame” of a population and its cultural alterations? Logically the only way to make such a distinction would be to move people into different environments or to change their cultural practices and then see what aspects of their physical and behavioral makeup did not change. But such an experiment is effectively impossible to perform, just as contemporary attempts to segregate heredity and environment are compromised both theoretically and methodologically (Lewontin [1974] 1976). Stereotypes about different populations and environments carry most of the explanatory weight.

This is an important part of the conceptual foundation of Western thought about races, ethnic groups, nations, and constitutional types. To this day it seems common-sensical to explain the character of people to some extent in terms of the place they have come from. Racial slurs, and racial praise as well, are often linked to place—the interiorization of the external environment is widely used as a principle for explaining human behavior. In the Western world, at least, the question “Where are you from?” really means “What kind of person are you?” That most of us know where we come from at least a few generations back and where most of our friends and colleagues are from tells us something about the continuing power of the connection between people and places in our systems of classification.

The ambiguities in Hippocrates’ views are also still with us. The problem of distinguishing between environmental influences caused by nonhuman and human agents is compounded by the tendency of people to move around. Once people have moved away from their place of “origin,” the theory encounters a serious problem.

The basis of the theory is a direct, immediate material connection between the environment, the humors, and behavior. When a group of people who have lived for many generations in one kind of environment move to another, theoretical consistency demands that the new environment should take over completely and modify the humoral constitution of the population. But this idea conflicts both with a theoretical principle in Hippocrates’ text and with common-sense observation.

The genealogical principle in humoral/environmental theory insists that people get their humoral constitutions not merely from the direct action of the environment but from their parents by physical transmission. The observation of parent-child similarities and the concept of blood as the source of shared physical substance among kin suggests that people are what they are in part because of the people they are descended from, and not merely because of where they are. A groups that moves into a new environment will still be partly formed by its genealogical connections with its past and will only gradually change in the new environment, possibly by means of the sorts of mechanisms Hippocrates discusses in regard to the Macrocephali.

Thus the total application of the humoral/environmental theory as a direct explanation of the character of peoples through immediate physical causes seems very powerful, but too strict an application of it comes into conflict with the genealogical principle of humoral constitution and with the observed persistence of cultural practices. Thus an enormous breach is opened in the conceptual structure. Any behavior not immediately attributable to local humoral/environmental causes can be attributed to genealogical connections by way of inherited humors from other environments or as survivals. Any failure of people to behave as their families, ethnic groups, or national governments wish can be met with the view that their excellent genealogy has been sullied by the nefarious influence of a hostile environment or mixture with “inferior” races.

It is apparent that this breach has provided the basis for most of the arguments about nature versus nurture right up to the present. The extreme environmentalist explains deviations from expectations by invoking genealogical and/or cultural causes that prevent the environmental influences from fully expressing themselves. The extreme genealogist (and likewise the cultural determinist) can explain deviations from the theoretically expected behaviors by invoking the contaminating influences of environment.

Jean Bodin (1529[?]–1596)

In the seminal works of Jean Bodin (heavily relied upon by Montesquieu and many others) we can see a clear continuity between the classical theories of the humors and environments on the one hand and contemporary political theory on the other. Bodin lived during the great wars of religion and the major European overseas expansions. In his major works, Six Books of the Commonwealth and Method for the Easy Comprehension of History (published in 1576 and 1583, respectively), he develops a theory of the political management of states based on an analysis of the influence of the environment on human behavior. He attempts to differentiate what is “natural,” and therefore beyond human control, from what is “political,” and thus subject to human design. He examines cultural differences around the world and in doing so provides exemplifications of the ambiguities in the humoral/environmental theory which are still with us.

In Book 5 of Six Books of the Commonwealth, Bodin postulates that the diversity of races requires different kinds of commonwealths.

Political institutions must be adapted to environment, and human laws to natural laws. Those who have failed to do this, and have tried to make nature obey their laws, have brought disorder, and even ruin, on great states. One observes very great differences in the species of animals proper to different regions, and even noticeable variations in animals of the same species. Similarly, there are as many types of men as there are distinct localities. Under the same climatic conditions oriental types are different from occidental, and in latitudes at equal distances from the equator, the people of the northern hemisphere are different from those of the south. What is more, when the climate, latitude, and longitude [are] the same, one can observe variations between those who are mountaineers, and those who live on the open plains. Even in the same city there is a difference in humour and in habits between those who live in the upper and those who live in the lower parts of the town. This is why cities built in hilly country are more subject to disorders and revolutions than those situated on level ground. … A wise ruler of any people must therefore have a thorough understanding of their disposition and natural inclinations before he attempts any change in the constitution or the laws. One of the greatest, if not the principal, foundation of the commonwealth is the suitability of its government to the nature of the people, and of its laws and ordinances to the requirements of time, place, and persons. For although Baldus says that reason and natural equity are not conditioned by time and place, one must distinguish between universal principles, and those particular adaptations that differences of places and persons require. The governments of commonwealths must be diversified according to the diversities of their situations. The ruler must emulate the good architect who builds with the materials locally available. The wise statesman must do this too, for he cannot choose such subjects as he would wish. [Bodin (1576) 1955:145–46; emphases mine]

In developing a set of associations between particular environments and particular kinds of human beings, Bodin elaborates on geopolitical stereotypes that are with us to this day. “Northerners succeed by means of force, southerners by means of finesse, people of the middle regions by a measure of both” (p. 148). He links these characteristics to the humors:

Those who live at the extremities near the poles are phlegmatic and those in the extreme south, melancholic. Those who live thirty degrees below the pole are of a more sanguine complexion, and those who are about midway, sanguine or choleric. Further south they become more choleric or melancholic. They are moreover tanned black or yellow, which are the colours of black melancholy and yellow choler. [Pp. 149–50]

Note that the humors are clearly the source of our contemporary color classification of races: white/phlegm, yellow/yellow bile, red/blood, and black/black bile. This connection between humors and races must be widely known but I have not found a reference to it in histories of racism.

The humoral color itself is insignificant, as people do not really come in these colors. Rather the color associates the predominance of a humor with a behavioral stereotype associated with each racial category. Thus American Indians are savage and warlike; blacks are lethargic and slow-witted; Orientals are cunning; and whites, not surprisingly, are reflective and rational.

Bodin equates the northern, southern, and temperate zones with the three ages of man: youth, old age, and maturity. “Northerners rely on force, those in the middle regions on justice, and southerners on religion” (p. 151). Predictably he decides that the people in the temperate zone are best suited for managing commonwealths.

Throughout his two major books, Bodin is concerned to understand the “natural” inclinations of different races in order to do two things. First, he wants to evaluate their historical deeds fairly. He believes it is unfair to criticize or to praise a northerner for being warlike, since belligerence is his “natural inclination.” Correct evaluation of history depends on understanding what people are constrained to be like, not blaming or crediting them from behaving as they naturally must.

Second, as a political reformer, Bodin wants to be able to suggest the form of government that would fit the “natural inclinations” of each race of people, since it is impossible to govern all people as if they were the same. The humoral/environmental differences among them would make such a project fail. Bodin demands a recognition of natural diversity harnessed to a program of political diversity in the name of a more abstract general human equality.

Bodin himself is clearly troubled by two parts of his own argument, and both are relevant to our concerns. Characteristically for his time, he worries about the religious implications of his views. According to the literal interpretation of the Bible, God created all humanity. How, then, could God have created humans of unequal abilities? Bodin provides a very weak answer:

Not that God respects either places or peoples, or fails to put out His divine light over all. But just as the sun is reflected more brilliantly in clear still water than in rough water or a muddy pool [read northern and southern races], so the divine spirit, so it seems to me, illumines much more clearly pure and untroubled minds than those which are clouded and troubled by earthly affections. [Pp. 152–53]

The argument makes little sense. If God is all-powerful, then creation is not constrained by rough waters or muddy pools. Ultimately his views assert the inequality of races. His view of inequality, connected with the political argument that matches different kinds of people to different forms of government, justifies both the suppression of minorities and imperialism. It is a short step from Bodin’s position to the polygenist view of races as separate creations.

Another problem Bodin faces is the relationship between the “natural” inclinations of a people and the state’s ability to modify these inclinations by cultural means. The conflict between nature and nurture is dramatically expressed: “Whatever laws or ordinances are made to diminish it, the natural inclination of the people will always reassert itself” (p. 152). Yet “there are of course men of all kinds of temperament in all localities and countries, though more or less subject to these general conditions which I have described. Moreover the particular can greatly modify the general character of the country” (p. 154).

Then, moving even farther in this direction, Bodin says:

If anyone would understand how nurture, laws, and customs have power to modify the natural disposition of a people, he has only to look at the example of Germany. In Tacitus’ day its inhabitants knew neither laws, religion, the sciences, nor any form of commonwealth. Now they are second to none in all these achievements.… On the other hand the Romans have lost the greatness and virtue of their fathers and are nowadays idle, mean, and cowardly. … If the discipline of laws and customs is not maintained, a people will quickly revert to its natural type. [Pp. 156–57; emphasis mine]

Finally, he proposes to derive policy guidelines from this complex web of conflicting causes:

So much for the natural inclinations of peoples. As I have said, this compulsion is not of the order of necessity. But it is a very important matter for all those who are concerned with the establishment of the commonwealth, its laws and its customs. They must know when and how to overcome, and when and how to humour these inclinations.

[P. 157]

Thus people are as they are because of the place their race came from originally. They bear the humoral/environmental stamp of the locality. At the same time, culture has a capacity to modify these natural inclinations and to bring great changes in people’s behavior. But Bodin also says that when political discipline is relaxed, people always have a tendency to revert to their “natural type” (which presumably is maintained through the genealogical connections with the environments in which they were formed).

Thus in Bodin’s view a kind of internal war is waged between nature and culture, and politics is enlisted in the battle on culture’s side. Humans are dominated by direct environmental influences, but we are also genealogically connected to past environments and culturally able to modify our behavior against the environment’s demands. These contradictions are politically important because Bodin justifies political action as the result of an impartial assessment of the “natural types” of people in different places.

Since there is no impartial way of deciding what any person’s “natural type” is, how do we know when people are acting against their “natural type”? Only by means of agreed-upon stereotypic national, ethnic, or racial histories. Thus Bodin’s appeal to nature as a guide to political conduct leaves an open field for manipulation while justifying ethically any of a host of political interventions.

Constitutional Types

A more specific connection between environments and physical types is made in the large literature on constitutional types. A tremendous diversity of material is available on the relationship between the physical constitutions of people, the environment, and their behavior. There are even putative correlations between certain physical types and position in the social hierarchy.

Though this intellectual arena has not been treated integrally by scholars, it is certainly well organized by people in the ordinary business of life. People respond differently to people of differing physiotypes. Leaving aside sexual differences, there are clearly somewhat different expectations for tall, thin people than for short, fat ones, for dark people than for light people, and so on. When people are asked to make up stories about individuals whose appearances differ, the stories vary in accordance with the appearances described. These complex symbologies of the body and its adornment have not yet been given the attention they require.1

In multicultural situations, differences in aesthetic preferences and in the general symbology of the body often lead to alienation or at least confusion. People who are perceived to be too dark, to flap their arms too much, or to move too slowly are hard to deal with. Each era has its caricatures of the physiotypes associated with different social classes and ethnic groups. Pat and Mike are more than names; they invoke appearances as well. How many medieval representations of a usurer who was tall, well-muscled, and light are there? Apparently, then, these physiotypes play an important role in the construction of the everyday world of meanings.

Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy

Throughout the history of Western thought attempts have been made to systematize categories of constitutional types into more fully organized and presumably more scientific systems. Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, a famous example of this genre published in 1621, is now generally treated as a work of literature. Burton sought to explain and to list all of the manifestations and cures of the predominance of black bile, the humor believed to cause melancholy. He concentrated on melancholy because he considered it the most pernicious of all the humoral disorders.

The scope of afflictions included under the heading of melancholy is wide, from “inequality” to mental illness. Each ailment is carefully defined and subdivided, and a hierarchical order of treatments is set forth. In Burton’s view, all behavioral states are caused by the effects of humors and the impact of the environment on them. Individuals differ in the degree to which these influences express themselves and in their responsiveness to treatments designed to counteract them.

The 1338-page modern edition of Burton’s book is exceedingly rich in the detailed analysis of humoral concepts and constitutional types; it includes a multitude of references and constructs a complex world of sickness and health on the basis of humoral ideas. Between Burton and present-day thinkers stretches a long tradition of the analysis of constitutional and racial types. Phrenology and other such typological systems have always had great appeal. Concepts of the neurasthenic young romantic, the gluttonous, gout-ridden old man, and the tubercular heroine were and are widely used in both literature and medicine.2

Francis Galton

No clear distinction is to be made between ideas about constitutional types and popular Western views on fixed racial characters. Already in Hippocrates and Bodin we have seen the connection between ideas about racial characters and humoral/environmental conditions. From them it is only a short step to the racial and eugenic ideas of Francis Galton.

This fact is well known. It should be regarded as a problem to be explained, however, because Francis Galton wrote after the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species and claimed to be a thoroughgoing evolutionist. The continuity between Galton and his pre-Darwinian predecessors is thus an example of the kind of simple continuity in humoral/environmental (and thus nonevolutionary) ideas I seek to uncover.

Galton, Darwin’s cousin, is well known for his numerous writings on statistics, fingerprinting, twin studies, blood transfusions, criminology, meteorology, and travel. He is perhaps best remembered for his work in eugenics. His fame began in 1869 with Hereditary Genius, a book that Darwin cited with admiration. Written in the language of Darwinian evolutionism, the book contains a complex statistical apparatus that tries to make his conclusions appear to be the results of scientific investigation. Much of the argument is still current today.

Galton begins by stating that he wrote the book to contradict the idea that the mind is free of the effects of “natural laws.” From his vantage point, there are only two sources of human behavior: the inborn (hence natural) and the acquired (hence cultural). It is his intention to place genius on the side of nature, just as Hippocrates and Bodin did. Galton, however, was an unabashed racist.

The natural ability of which this book mainly treats, is such as a modern European possesses in a much greater average share than men of the lower races. There is nothing either in the history of domestic animals or in that of evolution to make us doubt that a race of sane men may be formed, who shall be as much superior mentally and morally to the modern European, as the modern European is to the lowest of the Negro races. [Galton (1869) 1962:27]

Galton saw races as fixed ideal types:

… differences… between men of the same race might theoretically be treated as if they were Errors made by Nature in her attempt to mould individual men of the same race according to the same ideal pattern. Fantastic as such a notion may appear to be when it is expressed in these bare terms… it can be shown to rest on a perfectly just basis. [P. 28; emphasis removed]

This and related arguments about regression to the filial, parental, and racial “center” demolish variation as the source of human evolution. This idea alone severs the connection between Darwinism and Galton’s views. The denial of the evolutionary potential of variability is crucial for Galton because it allows him to argue for a social policy of eugenics to control the future of humanity. He argues against any other possible sources of human change in order to justify his policy.

How, then, did the races get their characteristics? Galton is ambiguous on this point. He speaks of the “natural refinement” of the Huguenots (p. 38) and says that “the natural temperaments and moral ideas of different races are various” (p. 39). It appears that races are as they are because they were as they were.

Later the argument becomes even less clear. He calls the British a race; judges a race; lowland Scots, English northcountrymen, and Athenians races. He also speaks of “civilized races.” In a peculiar passage, he even cites the “race-destroying” influences of “heiress blood.” It seems that men of great ability tend to marry heiresses, and as heiresses tend to come from relatively infertile families (or the women would not inherit large estates), such matches lead to low fertility in the families of men of great ability.

Given the array of uses of the term “race,” it is hard to pin down what Galton sees as the cause of racial differences. It is clear that he believes that races became as they are long ago. He sees the effect of civilization as “either… modifying the nature of races through the process of natural selection whenever the changes were sufficiently slow and the race sufficiently pliant, or of destroying them altogether when the changes were too abrupt or the race unyielding” (p. 399). And in passages that sound remarkably like arguments of Konrad Lorenz ([1963] 1971), Robert Ardrey (1966), and Desmond Morris (1969), Galton argues that there is a lack of synchrony between the requirements of modern civilization and the habits we have derived from our savage ancestors. The moral of the story is that we must intervene to make ourselves suitable to our civilization.

In Gabon’s view, a race cannot be much improved by natural selection, but it can be ruined. When the original “natural” races (which were apparently not created equal) are intermixed, the fine qualities of the naturally higher races are corrupted. Indeed, he argues that the degeneration of Athens was caused by the loss of its racial “purity.”

The core chapters of the work are surveys of various categories of preeminent people in Britain. Galton argues that superior men are “naturally” better equipped to compete in society than are others. They successfully overcome social hindrances and rise to the top quickly. To support this proposition, he attempts to trace the statistical incidence of genius in the higher occupational groups. Not surprisingly, he finds that hereditary genius makes men successful.

The serious social problem he sees is that these superior men show a markedly lower fertility than do inferior men. Society will be ruined unless we take control of our collective destiny and develop a positive eugenics program. He closes with the following statements:

Nature teems with latent life, which man has large powers of evoking under the forms and to the extent which he desires. We must not permit ourselves to consider each human or other personality as something supernaturally added to the stock of nature, but rather as a segregation of what already existed, under a new shape, and as a regular consequence of previous conditions.… There is decidedly a solidarity as well as a separateness in all human, and probably in all lives whatsoever; and this consideration goes far… to establish an opinion that the constitution of the living Universe is a pure theism, and that its form of activity is what may be described as co-operative.… It also suggests that they [individuals] may contribute, more or less unconsciously, to the manifestation of a far higher life than our own, somewhat as—I do not propose to push the metaphor too far—the individual cells of one of the more complex animals contribute to the manifestation of its higher order of personality. [Pp. 427–28]

This sort of comprehensive justification for eugenic controls and the suppression of individual freedoms has been made often since Galton.

Galton clearly regarded nature as a realm of physical laws, in contrast with culture, which is a realm of rational argument and action. He regularly contrasts law with will, ability with education, instinct with reason, and fixed with variable phenomena. While all these contrasts are important, the last one is startling. To refer to hereditary phenomena as fixed is to contradict a core principle of the evolutionary doctrines Galton claims to be relying on.

Galton’s argument hangs on the fixity of species; his only dynamic idea is that races degenerate through intermixture. The “natural” races are fixed unless we use culture to improve them. If we do not control nature with our reason, then the continuing mixture of races will ultimately breed away all outstanding human characteristics.

The book is peppered with references to purity of blood, mixture of blood, breeds, and other notions that show that Galton’s views on social hierarchy and racial differences were drawn from pre-evolutionary ideas. Galton believed that people are socially superior because of their superior bloodlines. It thus appears that Galton simply updated part of the terminology of the humoral justification for social inequality. The more recent history of such racist thought has been admirably analyzed by Stephen Jay Gould in The Mismeasure of Man (1981).

Ernst Kretschmer

Galton’s celebrity makes him a frequent target for just the sort of criticism I am offering. But the simple continuation of pre- and non-evolutionary ideas about “human nature” occurs in many less spectacular contexts. It remains influential and touches many lives in important ways.

The psychiatrist Ernst Kretschmer endeavored to use constitutional typology to place the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness on a scientific basis. He began his major work, Physique and Character (first published in English in 1921), with the following statement: “Investigation into the build of the body must be made an exact branch of medical science. For it is one of the master-keys to the problem of the constitution—that is to say, to the fundamental question of medical and psychiatric and clinical work” (Kretschmer 1925:5). Although body form is not identical with the constitution, the constitution of an individual can be inferred from his or her body form. Kretschmer felt the major problem in getting at this form was the lack of a refined typological system. He thus created the following scheme for diagnostic observation (the subcategories have been omitted):

-

FACE AND SKULL

Head, Eyes, Nose, Mouth, Lips, Cheekbone, Lower Jaw, Chin Larynx, Teeth, Gums, Ears, Forehead, Profile, Frontal, Outline, Facial form, Cranium, Back of Head

-

PHYSIQUE

Poise, Bone structure, Joints, Musculature, Fat upholstery, Head, Legs, Hands, Feet, Shoulders, Chest, Stomach, Spine, Pelvis

-

SURFACE OF THE BODY

Skin, Blood-vessels, Hair

-

GLANDS AND INTESTINES

Testicles, Genitalia, Thyroid gland, Lymph-glands, Mammary-glands, Internal diseases

-

MEASUREMENT

Height, Circumference, Length, Breadth, Skull

-

TEMPORAL

Commencement of mental disturbance, Commencement of puberty, Commencement of involution, Commencement of fattening, Commencement of emaciation, Commencement of baldness, Commencement of certain physical disorders, Sexual abnormalities

- SUMMING UP OF PHYSICAL STATES

- TYPE OF PERSONALITY

- HEREDITY

[Pp. 5–8]

Each of these general categories has a set of subcategories for measurement and classification. Despite its apparently large number of categories, this scheme is exceedingly simple. Anyone with a little experience in anatomical description would find it adequate only for getting at the grossest features. It is also static: the body in motion cannot be captured in this typological system. Yet Kretschmer is reasonably satisfied that this scheme can be used to put constitutional typology on firm scientific ground.

To “test” the classification and to provide a set of statistical values for comparison, Kretschmer applied this scheme to a population of Schwabians. He enters an interesting caveat: “… without further work they [the results] cannot be compared with numerical values obtained from patients belonging to other races” (pp. 12–13; emphasis mine).

Though he is quite properly cautious about the problem of statistical sampling, he simply calls the Schwabians a “race.” While this usage was commonplace in references to many regional populations in Europe and the United States, it suggests a fundamental primitivism in Kretschmer’s grasp of the methodological and theoretical problems of biological taxonomy, despite his belief that he was making a major contribution to just this field.

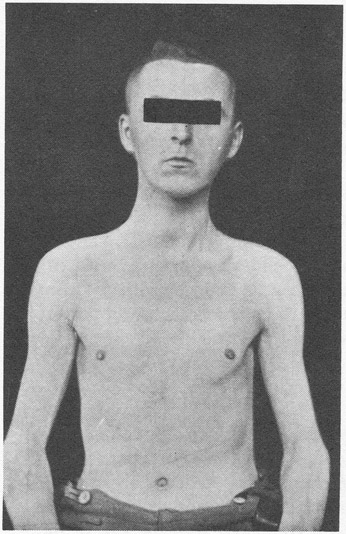

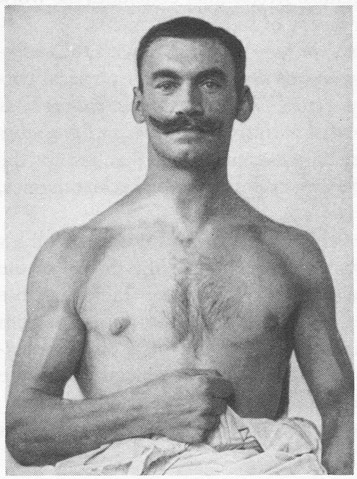

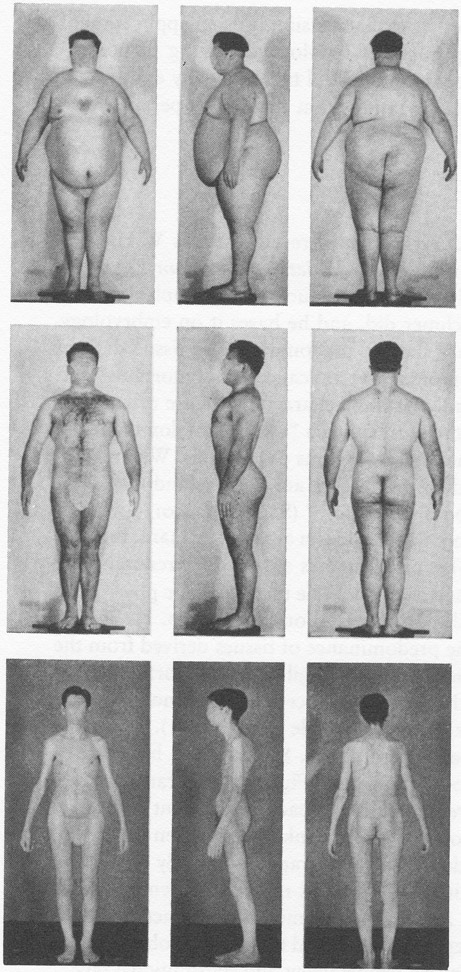

Kretschmer is stern in his criticism of previous attempts at constitutional typology, particularly their lack of objectivity. To replace previous classificatory types, he introduces his own general types: the asthenic, the pyknic, and the athletic, and a mongrel misfit or antitype called the dysplastic. Figures 4, 5, and 6 show the photographs he offers as examples of the first three types. Armed with these types and a set of arguments about the behavioral tendencies associated with each, he constructs his theory of temperaments.

He believes these types to be “real” in some ultimate sense: “The types… are not ‘ideal types’ which have emerged… in accordance with any given guiding principle of collection or pre-established values. They are… obtained from empirical sources …” (p. 18). And he says:

It is the same here as in clinical medicine, or in botany or zoology. The ‘classic’ cases, almost free from any mixture, and endowed with all the essential characteristics of a perfect example of some form of disease, or a zoological race-type, are more or less lucky finds, which we cannot produce every day. From this it follows, that our description of types… refers not to the most frequent cases, but to ideal cases… [P. 19; emphasis mine]

This strange bit of illogic is singled out to show that Kretschmer, despite claims of objectivity, is actually working with a small set of aesthetic ideals drawn from Western culture, ideals of which real people are more or less (usually less) perfect embodiments.

He characterizes the physiotypes in the following manner. His asthenic type is described as having “a deficiency in thickness combined with an average unlessened length.” The asthenic type is “a lean narrowly-built man, who looks taller than he is, with a skin poor in secretion and blood, with narrow shoulders, from which hang lean arms with thin muscles” (p. 21; emphasis removed). His pyknic type

is characterized by the pronounced peripheral development of the body cavities… and a tendency to a distribution of fat about the trunk, with a more graceful construction of the motor apparatus… middle height, rounded figure, a soft broad face on a short massive neck, sitting between the shoulders; the magnificent fat paunch protrudes from the deep vaulted chest which broadens out towards the lower part of the body. [P. 29; emphasis removed]

The male athletic type

is recognised by the strong deveopment of the skeleton, the musculature and also the skin.… A middle-sized to tall man, with particularly wide projecting shoulders, a superb chest, a firm stomach, and a trunk which tapers in its lower region, so that the pelvis, and the magnificent legs, sometimes seem almost graceful compared with the size of the upper limbs and particularly the hypertrophied shoulders. … The outlines and shadings of the body are determined by the swelling of the muscles of the good or hypertrophied musculature which stands out plastically as muscle-relief. [P. 24; emphases mine]

There can be little question which type is the best.

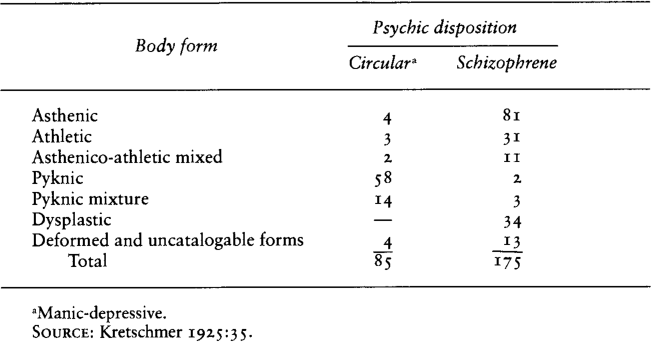

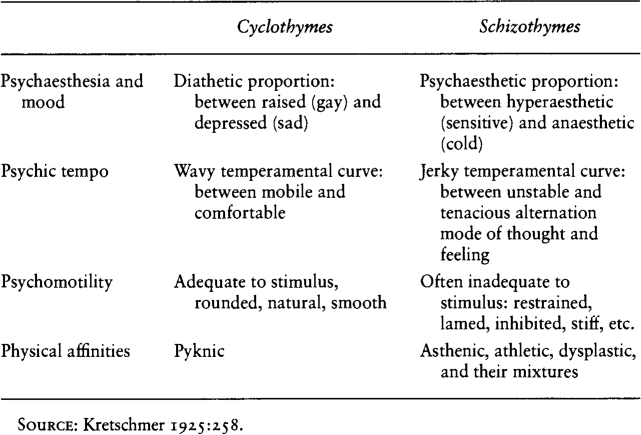

Kretschmer correlates these types with “circular” (manic-depressive) and “schizophrene” psychic dispositions (Table 1). From these data he concludes that

we can formulate our results straight away. (1) There is a clear biological affinity between the psychic disposition of the manic-depressives and the pyknic body type. (2) There is a clear biological affinity between the psychic disposition of the schizophrenes and the bodily disposition characteristic of the asthénies, athletics, and certain dysplastics. (3) And vice versa, there is only a weak affinity between schizophrene and pyknic on the one hand, and between circulars and asthénies, athletics, and dysplastics on the other. [P. 36]

A long set of chapters on various forms of mental illness in relation to constitutional types is followed by a chapter on the relation between constitutional type and genius. Kretschmer concludes the work with an attempt to formulate a theory of the temperaments.

FIGURE 5 Kretschmer’s pyknic type, described as “circular” (manic-depressive) (Kretschmer 1925, pl. 3)

TABLE 1 Number of Kretschmer’s subjects who displayed “circular” and “schizophrene” psychic dispositions, by body form

Temperament, Kretschmer says, is “co-determinate with the chemistry of the blood, and the humours of the body. Their physical correlate is the brain-glandular apparatus. The temperament is that class of mental events which is correlated with the physique, and probably through the secretions” (p. 252; emphases mine). He then groups the temperaments into two major classes, cyclothymes and schizothymes, which he sums up in Table 2.

I submit that Kretschmer’s entire formulation was not based on his observations at all, but on a resystematization of the theory of the humors. He uses humoral language, and we can see in Table 2 a close connection to the older humoral classifications. From top to bottom we move from those characterized by behaviors typical of the prevalence of blood and yellow bile down through the phlegmatic to the melancholic. Figures 4, 5, and 6 fit this classification equally well.

TABLE 2 Psychological and physical characteristics associated with Kretschmer’s two classes of temperament

Virtually nothing of evolutionary biology is found in Kretschmer’s theory; his whole system can be explained simply as an application of humoral doctrines. His approach is typological, resting on the assumption that natural categories and ideal types actually exist in nature. Variation is treated as deviation from the ideal type, and ideal types are seen as static.

W. H. Sheldon

The major constitutional typologist of recent times is W. H. Sheldon, whose most widely read book, Varieties of Human Physique, was published in 1940. Sheldon uses a much more complex classificatory scheme than Kretschmer did, and he bases it on embryology. Constitutional features that show a predominance of tissue derived from the endodermal embryonic layer are called “endomorphic,” and persons with a predominance of these characteristics are called “endomorphs.” He describes them as having a “relative predominance of soft roundness through the various regions of the body. When endomorphy is dominant the digestive viscera are massive and tend relatively to dominate in the bodily economy” (Sheldon 1940:5).

When tissues derived from the mesoderm are predominant, the type is called “mesomorph.” This physique has a “relative predominance of muscle, bone, and connective tissue. The mesomorphic physique is normally heavy, hard, and rectangular in outline…” (p. 5). Finally, “ectomorphy” refers to the predominance of tissues derived from the ectoderm and thus of “linearity and fragility. In proportion to his mass, the ectomorph has the greatest surface area and hence relatively the greatest sensory exposure to the outside world” (p. 5).

Starting with these three general types, Sheldon and his team of researchers took some 4,000 photos (see Figure 7) and rank-ordered them according to the predominance of each component in five regions of the body for a total of fifteen rank orders. Then anthropo-metric measurements made of the photographs eventually resulted in eighteen anthropometric indices. Using all these measurements, they eventually came up with a three-digit numeral to characterize each photograph. By this process Sheldon hoped to create an objective science of the relationship between temperament and constitutional type.

Sheldon asserts that these body types correlate with temperaments in the following way:

Basic aspects of temperament have been identified, objectified by the method of tests and interviews, and scaled on 7-point scales. These components we refer to as viscerotonia, somatotonia, and cerebrotonia.

Viscerotonia is roughly identifiable with love of comfort, relaxation, sociability, conviviality, and sometimes with gluttony. It is the motivational organization dominated by the gut and by the function of anabolism. Somatotonia is the motivational pattern dominated by the will to exertion, exercise and vigorous self-expression. It is the drive toward dominance of the functions of the soma. Cerebrotonia refers to the attentional and inhibitory aspect of temperament. In the economy of the cerebrotonic individual the sensory and central nervous systems appear to play dominant roles. He is tense, hyperattentional and under strong inhibitory control. His tendency is toward symbolic expression rather than direct action.

These components of temperament appear to correlate with patterns of somatotypes, and like the morphological components, they combine in various proportions in different individuals. They behave, within limits, as independent variables. [Pp. 8–9; emphasis his]

FIGURE 7 Sheldon’s endomorph (top), mesomorph (middle), and

ectomorph (bottom) (Sheldon 1940, frontispiece)

These somatotypes and their associated mental orientations are compatible with Kretschmer’s constitutional types and with earlier humoral typologies. Sheldon multiplied the measurement techniques but he did not change the rules of the game.

Sheldon has a strong sense of the larger social utility of these typologies. He believes that somatotyping provides a basis for the creation of racial norms (once we have seen the relative distributions of these types among the various races). Following this fanciful use of the concept of race, he states that “we have discovered no case in which there has been a convincing change in the somatotype” (p. 221). Thus not only will we have clear racial types, but they will be unlikely to change over time.

He argues that “by constructing and applying a simple scale for measuring the relative strengths of motivational drives, we have not only found that analogous elemental components appear to express themselves in temperament almost as clearly as in physical constitutions, but we have been able to measure three elemental components with some reliability” (p. 225). Sheldon advocates somatotyping of children because “we need to dispose the influences to which children are exposed in such a manner that youngsters set their hearts upon values which represent the fulfillment of their own constitutional potentialities” (p. 227).

But what does this mean? On the one hand, Sheldon has stated that there is a direct connection between somatotype and temperament and that somatotype does not change. On the other he states that “there is little question that some change in external and manifest motivation takes place in response to educational and environmental influence” (p. 226). He thus categorically states one proposition, then its opposite, and asserts that both are true.

This is not some special defect in Sheldon’s thought. This ambiguity has already been noted in the arguments of Hippocrates, Bodin, and Galton. In all these views, the material influences of the genealogical principle and of the direct environmental principle come into conflict and produce contradictions. For Sheldon these contradictions open up a major field of social manipulation. Those who make up the somatotypology and apply the method classify children into categories with fixed behavioral characteristics. They then assert that the children must adjust to their “natural” constitutions, although some modifications can be made. Just what modifications can or cannot be made are up to the somatotyper to determine.

Just as in the related case of IQ measurements, the somatotypes are seen as a system of relatively fixed capacities. Children of the wrong type—endomorphs, for example, should adjust their hopes to lives of uninventive toil. To try to educate children beyond the limits of their types is to lead them into lives of frustration.

Sheldon’s methodology, like Kretschmer’s, masks a process that brings the humoral typology of human characteristics forward again in new language. There is a direct correspondence between Sheldon’s somatotypes and humoral classifications.

His claim to be using the results of modern biomedical science is false. By “biological” Sheldon means only that which is fixed or unalterable. Since key elements in modern evolutionary biology are that biological processes and categories are in continuous flux, that new variation is continuously generated, and that no class of organisms is fixed in any ultimate sense, it is clear that Sheldon’s biology is non-evolutionary.

National Character and Ethnie Identities

Attributions of national character are yet another application of the same basic humoral/environmental theories to the explanation of the behavior and historical trajectories of nation-states. The literature is voluminous, diverse, and theoretically flaccid. It ranges from quantified nonsense to chauvinistic political tracts to Sunday travel-page homilies. The theoretical structure of national character arguments has hardly changed in the whole of Western history (Caro Baroja 1970).

I do not propose to delve deeply into this subject here. I only want to show that this major tradition of interpretation of history and justification of conduct rests on a humoral/environmental foundation. Before making this point, I shall evoke the flavor of this literature with examples from Spain, the country where I have done my own anthropological research.

National character attributions regarding the inhabitants of Spain began very early. Strabo was making assertions about the inherent character of the Iberians in the second century before Christ (Caro Baroja 1970). Both Muslim and Christian rulers exhorted their subjects with attributions of national character and destiny during the long battle over the Iberian peninsula. Perhaps most striking of all is the elaboration of the “black” and “white” legends centering on assertions that religious intolerance and greed, on the one hand, and strength in the Christian faith and military virtue, on the other, were intrinsic, natural characteristics of the Spaniards.3

The most notable thing about these national character views is the way they support political positions. At times we are told that the Spaniards are fanatical, avaricious, authoritarian, anarchical, or too proud to be governed. At other times the Spaniards are pictured as steadfast in the faith, ascetic, proud, and militant. Negative attributions are generally justifications for political action against Spain or for the failure of some group within the government to fulfill its promises. Positive attributions generally serve to justify governmental policy or the suppression of minorities, or simply to whip up national pride. This is still true in Spain and elsewhere.

Often national character portraits take on literary trappings. In his widely read book The Spanish Temper, V. S. Pritchett recounts the following episode:

Hendaye: the train dies in the customs. One gets a whiff of Spanish impossibility here. A young Spaniard is at the carriage window talking to a friend who is on the platform. The friend is not allowed on the platform; what mightn’t he be smuggling? The gendarme tells him to go. The Spaniard notes this and says what he has to say to his friend. It is a simple matter.

“If you go over to see them on Wednesday tell them I have arrived and will come at the end of the week.” But if a bossy French gendarme thinks that is how a Spaniard proceeds, he is wrong. The simple idea comes out in this fashion:

“Suppose you see them, tell them I am here, but if not, not; you may not actually see them, but talk to them, on the telephone perhaps, or send a message by someone else and if not on Wednesday, well then Tuesday or Monday, if you have the car you could run over and choose your day and say you saw me, you met me in the station, and I said, if you had some means of sending them a message or you saw them, that I might come over, on Friday, say, or Saturday at the end of the week, say Sunday. Or not. If I come there I come, but if not, we shall see, so that supposing you see them …” Two Spaniards can keep up this kind of thing for an hour; one has only to read their newspapers to see that they are wrapped in a cocoon of prolixity. The French gendarme repeats that the Spaniard must leave. The Spaniard on the platform turns his whole body, not merely his head, and looks without rancour at the gendarme. The Spaniard is considering a most difficult notion—the existence of a personality other than his own. He turns back, for he has failed to be aware of anything more than a blur of opposition. It is not resented. Simply, he is incapable of doing more than one thing at a time. Turning to the speaker in the train, he goes over the same idea from his point of view, in the same detail, adding personal provisos and subclauses, until a kind of impenetrable web has been woven round both parties. They are aware of nothing but their individual selves, and the very detail of their talk is a method of defeating any awareness of each other. They are lost in the sound of their own humming, monotonous egos and only a bullet could wake them out of it. [Pritchett (1954) 1965:7–8]

Pritchett has given us, in literary form, a pat explanation for the decline of the Spanish empire and for the Civil War. Spaniards are so egotistical that they are incapable of assessing real-world situations and therefore act with utter irresponsibility. The necessary result is armed violence. Spaniards are to blame for Spanish history.

This genre of writing is familiar to us all. A kind of extended Polish joke, such views are generally associated with serious inattention to power relationships, political economy, and social conflict.

The relationship between these national character portraits and the humoral/environmental theories is close. National characters have to come from somewhere. How did the Spaniards come to be as they are? There are basically only two answers. The Spaniards are as they are either because of the physical characteristics of the Iberian peninsula or because they were created (by God or some other initiatory principle) that way. Subsequent history subjects them to the influences of other people who come to the peninsula, but the “natural frame” persists nonetheless.

Among the most frequently cited causes of the supposed anarchism of the Spanish character and therefore the political disorders that have occurred in Spanish history are the highly broken topography, the great regional ecological diversity, the difficulty of communication between the political center and the peripheral regions, and the supposedly radical distinction between “wet” and “dry” Spain. Geography determines national character and history.

No matter which of the particular geographical features is given primacy, the strategy of explanation remains the same. It is familiar to us from the works of Hippocrates and Bodin. If the physical environment determines national character, there must be a way that environment gets inside of the inhabitants to have its effect, to become part of them. Thus national character attributions in which geography plays an important role, whether they be pre- or post-Darwinian, rely on a logic that belongs to the humoral/environmental theory. People are a product of their environment, not in the evolutionary sense of adaptation, but in a humoral sense: the environment directly determines the humoral balance in the population, and this balance in turn determines the national character.

Often this environmental determinist position is found in a confusing mix with some kind of genealogical myth. Using the Bible as a source of information, many national character writers have tried to connect the contemporary population of Spain, or of any other European country, with biblical figures. At the initial creation of the divergent groups of human beings, the fundamental differences between them were set. Subsequent history moved them around the landscape until the modern nations emerged. In this view the genealogical principle is clearly central. Nationalities were created and have “bred true” since then. The only changes in their behavior have been wrought by the environments into which they have been forced to move.

These environmental and genealogical views are often combined to create an ambivalent explanation of national character. Eléna de la Souchère approximated Hipprocrates’ view when she wrote in 1964 regarding the fatal flaw of excessive individualism in the Spanish character: “This innate individualism was to become more specific, emphasized by the environment and, from the first, by the long struggle of Spanish men against an arid land” (la Souchère 1964:15). This is the very ambiguity that characterizes the views of Hippocrates, Bodin, and the great mass of thinkers who seek to explain social structure and political behavior on the basis of “natural” differences between human beings.

Conclusion

The catalogue of thinkers could go on almost indefinitely. The controversies over immigration quotas and the outbursts of racism in the 1930s and 1940s are well known to us all. The underlying conceptual structures have much in common with those discussed here. Thus I conclude that in the vast recent literature on races, national characters, constitutional types, and eugenics, pre-Darwinian humoral/environmental ideas prevail, despite regular attempts to claim the support of evolutionary theory.

Our cultural tradition finds it exceedingly attractive to anchor explanations of behavior of groups of people in an original place of creation. That place may be in the hand of God or in a particular physical environment, but it stamps the “nature” of a people forever. To the extent that subsequent modifications occur, they occur only as alterations in that basic “natural frame.”

What predominates is a view of different races, nations, constitutional types, and social classes as fixed categories with little internal variability and no capacity to produce future variability. All of these theories reject so-called mongrel alliances because mixture of pure types generally causes social degeneration.

In view of evolutionary biology’s emphasis on the continuous production of variability and the complex nondirectional dialogue between the variability produced and the variety of environmental pressures to which these variants are subjected, it is clear that the claims of any of these theories to be evolutionary or or to represent the findings of modern science are false.