But how could men, trained to teach one and another superstition, wrapt in all the prejudices of their heredity and their caste, accept such arguments as those even if they had heard of them? The mere idea that man might regenerate himself without the aid of the supernatural was impious to their minds; the idea of stating the truth plainly, of rousing people by shocking them, was horrible to their delicacy of feeling, for they belonged to a white-livered generation, whence all robustness had departed. Perhaps if this Zola had been one of themselves they might have tolerated him, but he did not bow to the supernatural, his creed was different, and he was therefore a rival, an enemy, particularly as he contemplated a world whence they would be banished, as it would need none of their ministrations.

Thus the campaign began and soon found an echo in the newspapers. At that time probably there were not twenty journalists in all England who had read Zola's essays and critical papers in which he defined his position and the purport of his novels. In the latter, as is well known, he abstained from preaching. There is nothing of the nature of a sermon in the whole series of "Les Rougon-Macquart" until one reaches "Le Docteur Pascal"; and one must admit that, although Zola had freely expounded his views elsewhere, the omission of those views from his novels was detrimental to him and them among those people who could not rightly understand any exposure of vice unless it were accompanied by preaching. Had he preached, the clergy, so many of whom believe preaching to be the chief function of their ministry, might well have been on his side, and even "Blackwood's Magazine" might then have hesitated to describe him as a man without a conscience. But he contented himself with picturing vice as vile, and the viler he made it appear, the more was he abused, the more was he accused of wallowing in it, of giving full rein to filthy libidinous propensities for the express purpose of corrupting all who read him! That charge was repeated widely by the English press, as is shown by the hundreds of cuttings from London and provincial newspapers in the writer's possession. And Vizetelly & Co. were accused of having deliberately chosen "the very worst" of Zola's books for translation.

As a matter of fact, in 1888 they were selling all the novels that Zola had then written, with the exception of "Les Mystères de Marseille," "La Confession de Claude," and "Le Rêve," which last only appeared in Paris in the latter part of that year. The publication of those books had been going on for four years, unchallenged. Each new volume as it appeared was priced at six shillings, and subsequently lowered to three shillings and sixpence. A few volumes, in picture boards, were sold at two shillings and sixpence. But the critics rushed upon "The Soil," the English version of "La Terre," and one man, who can never have compared it with the original, had the impudence to assert that it was "an almost word for word translation of Zola's bestial book." Readers who had never seen Vizetelly & Co.'s catalogue were also allowed to infer that the firm traded exclusively in "pornographic literature." Now, in that catalogue, two hundred and forty works were enumerated, and the Zola volumes were eighteen in number. But it may be said that other books were denounced also, the translations of Flaubert's "Madame Bovary" and "Salammbo"; Goncourt's "Germinie Lacerteux" and "Renée Mauperin"; Gautier's "Mlle. de Maupin"; Murger's "Vie de Bohême"; Maupassant's "Bel-Ami" and "Une Vie"; Daudet's "Sapho"; Paul Bourget's "Crime d'Amour" and his "Cruelle Énigme," which last the firm had issued in consequence of a laudatory notice in the staid old "Athenæum," surely the last journal in the world to recommend anything suggestive of pornography. But counting even all the works belonging more or less to the French realistic schools which Vizetelly & Co. issued, one reached only a total of about thirty, leaving some two hundred and ten books of other classes. Thirteen of those were certainly volumes of "The Mermaid Series of the old Dramatists" which some anonymous scribes likewise regarded as "pornographic" in that hour when cant and hypocrisy poured venom on virtually every form of literature that had not received the imprimatur of Pecksniff & Company

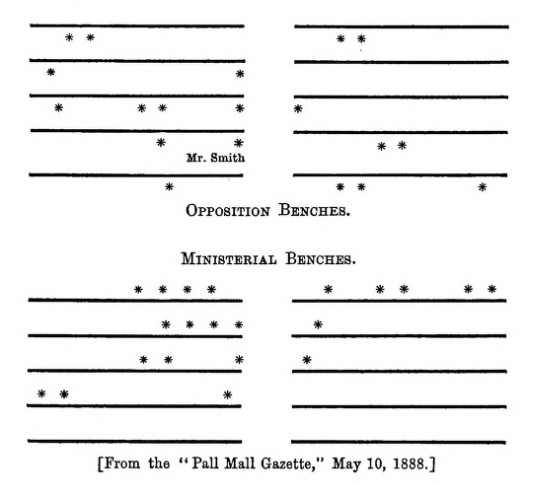

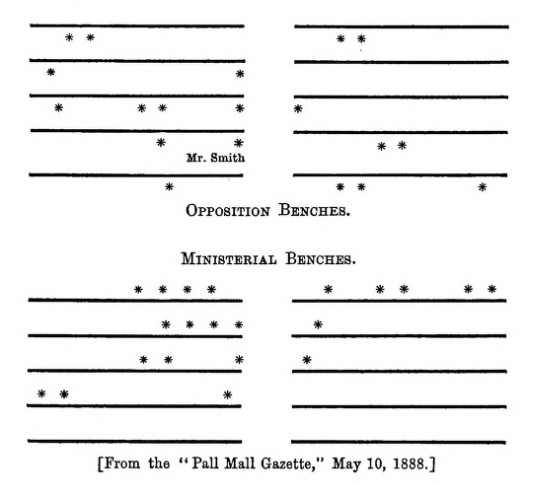

The public having been prepared for developments, the question of "pernicious literature" was brought before the House of Commons by one of its members, Mr. Samuel Smith, who sat for Flintshire. He had married the daughter of a clergyman, and had a reputation for extreme piety. He was described at the time as "an enthusiast without enthusiasm, with a tall, expansive frame, a huge beard, a placid-life-like expression, and a mild feminine voice,"[17] which, said another journal, was "peculiarly suited to the expression of lamentation."[18] There was some fear, it seems, that there might be a poor attendance at the debate on the motion he meant to submit, indeed a "count out" was feared, but arrangements were made to keep a house for the occasion, when the aspect of the benches was apparently such as the following diagram indicates:

Thus, of an assembly numbering between six and seven hundred members, just forty were found sufficiently interested in the morals of their constituents to discuss the motion submitted by Mr. Smith, which was: "That this House deplores the rapid spread of demoralising literature in this country, and is of opinion that the law against obscene publications and indecent pictures and prints should be vigorously enforced and, if necessary, strengthened." In the speech with which the member for Flintshire opened the debate he did not hesitate to describe Henry Vizetelly as "the chief culprit in the spread of pernicious literature"; and, according to a "Pall Mall Gazette" report, which he never contradicted, he said of the works of Zola that "nothing more diabolical had ever been written by the pen of man; they were only fit for swine, and those who read them must turn their minds into cesspools."[19] In this fashion does the Puritan prate when he goes on the warpath. For the rest, Mr. Smith talked de omni re scibili, "flinging his accusations broadcast. All kinds of literature, including daily newspapers, came under his ban. He wanted everything—books, magazines, and newspapers,—to be subject to some sort of restraint." He spoke in the "spirit which assumes that what is evilly suggestive to itself must be evilly suggestive to others." But as was added by the journal from which these remarks are quoted:[20] "What sort of literature should we have if it were all brought down to such a level as would satisfy the ascetic tastes of the Smiths? Where would the Bible be? What would become of Shakespeare?"

After Mr. Smith's motion had been seconded by Mr. T. W. Russell, and endorsed by Sir Robert Fowler and Mr. De Lisle, another member, Mr. (afterwards Sir F. S.) Powell, leaving French novels on one side, called attention to certain circulars "headed with Scriptural texts and looking like religious tracts" which were circulated in English homes, apropos of the spread of contagious disease in India, and which, in his opinion, were calculated to do much harm.

Then came the Government spokesman, Mr. Henry Matthews, one of the most unpopular Home Secretaries that Great Britain has known since the time of the Walpole under whose effete administration the public tore down the railings of Hyde Park. Mr. Matthews, a lawyer and a Roman Catholic, was subsequently given a peerage; but in 1888 he sat in the House of Commons for the city of Birmingham. He agreed very largely with what Mr. Smith had said, and he asserted that "in comparing French modern literature with classical literature it had to be borne in mind that, while the latter was written with no evil purpose(!), the former was written with the object of directing attention to the foulest passions of which human nature was capable, and to depict them in the most attractive forms"—an allegation which, applied to Zola's works, can only be described as astounding. But the Home Secretary also denounced the "penny dreadfuls," the quack advertisements, and the full reports of divorce cases which appeared in the daily press. And on the question of instituting prosecutions he said:

"The reason why the law was not more frequently put in force was the difficulty that was experienced in getting juries to draw a hard and fast line, and to convict in all cases that crossed that line. He had given careful attention to this question, and he should deprecate handing over to the Public Prosecutor, or anybody else, the task of deciding what was the straight and narrow line which divided what was punishable, criminal, and obscene within the meaning of the law, and what was merely indelicate and coarse. The public judgment was a safer guide than that of any official, and if the general moral sense of the community did not compel individuals to prosecute, no good would be done by trying to create an artificial moral sense by the action of the Public Prosecutor.... Serious evils arose from the failure of attempts to obtain convictions. So far, however, as he could influence the Public Prosecutor, who was, to some extent, independent of any Public Office and acted on his own discretion, he would certainly urge prosecutions in any cases in which it did not appear that more harm than good would result.... He was sure, however, that the hon. Member and all those who had honest convictions would not shrink from the slight personal inconvenience of putting the law in motion in any case of real public mischief."

The debate was continued by three or four members, one of whom, Mr. H. J Wilson (Holmfirth) apologetically and naïvely declared with respect to the pious circulars on the working of the Contagious Diseases Act, of which Mr. Powell had complained, that their distribution was the only method of making the truth known, and that the only way to stop them would be to put an end to the horrible system that rendered their dissemination necessary. To this Zola, if he had been present, might have retorted that the circulation of the plain statements of fact contained in his books was likewise, in his estimation, the only way to make known the degradation of society at large, in order that remedies might be applied.

Mr. Smith's motion was carried unanimously, however, by the forty gentlemen present, matters being left in this position: The Government hesitated to institute prosecutions, and thought that private individuals should do so.

Meanwhile the campaign went on. Mr. Smith wrote a letter to the newspapers; another came from Lord Mount-Temple; and the press, with few exceptions, endorsed everything that was said by the commoner and the nobleman. The vigilant "Guardian" of the Church of England availed itself of the occasion to thunder against Sir Richard Burton and his "Arabian Nights"; "The Tablet" of the Roman Catholics jesuitically signified its approval of the agitation, because Zola's whole tendency was "suspected"(!) to be immoral; the conscientious Nonconformist journals, as was to be expected, said ditto to everything that Smith said. Some righteous contributor to "The Globe" wrote of Zola's books that they were characterised by "dangerous lubricity," that they "sapped the foundations of manhood and womanhood, not only destroyed innocence, but corroded the moral nature." "The Birmingham Daily Mail" declared that "Zola simply wallowed in immorality." "The Whitehall Review" openly clamoured for the prosecution of his publisher. "The Weekly Dispatch" impudently inquired, "If Mr. Vizetelly gives us Zola, why does he pick 'La Terre'? And if Daudet, why pick 'Sapho'?"—thus ignoring the fact that the firm published virtually all of the former's stories, and several of the latter's, and conveying, for its own purposes, a false impression to its readers. Indeed, misrepresentation of the facts was to be found in many directions. A few newspapers wrapped themselves in their dignity and said nothing, and a few remained fairly cool and sensible: "The Standard," "The Scottish Leader," "The Scotsman," "The Radical Leader," "The Bradford Observer," "The Country Gentleman," "Piccadilly," "The Newcastle Chronicle," and "The Western Daily Press." There may have been a few others, for the writer does not claim that his collection of press cuttings is absolutely complete; but after examining some hundreds of extracts he finds little that is not mendacious or steeped in religious bigotry, puritanical prudery, or gross ignorance. And at all events it is certain that an overwhelming majority of British editors and "leader-writers" endorsed the views of the Pharisees.

The campaign was then carried to a decisive stage. A firm of solicitors, Collette & Collette, applied at Bow Street police-court for a summons against Henry Vizetelly for having published three obscene books, to wit, "Nana," "The Soil" ("La Terre"), and "Piping-Hot" ("Pot-Bouille"), by Émile Zola. The summons was granted, and on August 10, 1888, Vizetelly appeared to answer it. The prosecution had been entrusted to Mr. Asquith,—now best known as a politician,—and he, in opening his case, was about to deal with "Nana," when the magistrate, Mr. (afterwards Sir) John Bridge, who evidently had already made up his mind respecting the case, suggested that he should take the worst of the three books, namely "The Soil,"—for which, by the way, Zola had received the decoration of the Legion of Honour three weeks previously! Counsel assented, referred the magistrate to various pages, and then solemnly declared that this book and the two others were "the three most immoral books ever published!" But having thus revealed how very limited was his knowledge of literature, he added, fairly enough, that it was claimed for "The Soil" that it had been published with a high moral object—namely, to show the degradation of the French peasant and the necessity of alteration in the laws by which he was governed.

Vizetelly's solicitor, Mr. Lickfold (of Messrs. Lewis & Lewis), argued on his client's behalf that he had a perfect right to publish these translations, the French originals of which were circulated in Great Britain without let or hindrance; and he contrasted them with English works which were sold widely and freely, such as Byron's "Don Juan," and Shakespeare's "Merry Wives of Windsor." Far from the incriminated books being the three most immoral ever written, said Mr. Lickfold, there were many within the cognisance of all men of any education which were very much worse. But the magistrate curtly intimated that it was a case for a jury to decide, and he forthwith committed the defendant for trial at the Central Criminal Court, admitting him, meanwhile, to bail in his own recognisances.

Vizetelly's committal led to great rejoicing among the Pharisees; and to improve the occasion the "National Vigilants" summoned a bookseller named Thomson at Guildhall (September 7) for selling an English version of Boccaccio's "Decameron." Mr. Forrest Fulton—subsequently knighted and appointed Common Sergeant of the City of London—prosecuted and asked for a committal, but Mr. Horace Avory, defendant's counsel, replied that the "Decameron" had been in circulation for over four hundred years, that there were three copies of the work in the English language in the Guildhall Library and some two hundred in the British Museum; and he contended that this classical work was not indecent in the eyes of the law. Mr. Alderman Phillips, who heard the case, quietly remarked that he himself had read the book both in Italian and in English, and he refused to send the defendant for trial, as he did not believe that any jury would return a conviction.

This was a rebuff for the fanatics, who now concentrated their energy on the prosecution of Vizetelly. The latter had taken his committal in a defiant spirit, promptly issuing the following notice to his customers: "The trade is informed that there are no legal restrictions on the sale of 'Nana,' 'Piping Hot,' and 'The Soil,' and that none can be imposed until a jury has pronounced adversely against these books which the publishers still continue to supply." This announcement, which was perhaps ill advised—though in counsel's opinion well within one's legal rights—momentarily enraged the "Vigilants," but they were about to receive important help. The Government, encouraged by the press, took up the prosecution, thus relieving the agitators of the cost of their suit.

Affairs now began to assume a more serious aspect, the question was no longer one of fighting a band of fanatics, but of contending against the law-officers of the Crown who would bring all the weight of their authority to bear upon the jury. In these circumstances Vizetelly decided to print a series of extracts from the works of English classic authors,[21] by way of showing that if Zola's novels were suppressed one ought also to suppress some of the greatest works in English literature. These extracts, which were preceded by quotations from Macaulay on the suggested suppression of the works of Congreve, Wycherley, etc., and by Zola's own explanation of the scope and purpose of his Rougon-Macquart series, covered a very wide field. Among the many authors laid under contribution were Shakespeare, Beaumont and Fletcher, Massinger, John Ford, Thomas Carew, Sir George Etherege, Dryden, Congreve, Otway, Prior, Defoe, Swift, Sterne, Fielding, Smollett, Byron, etc., the series running from the time of Elizabeth to the early part of the nineteenth century. At the same time Vizetelly drafted an open letter to Sir A. K. Stephenson, the Solicitor to the Treasury, who now conducted the prosecution, and copies of the letter and of the extracts were forwarded to all the members of the Government and the leading London newspapers. The letter ran as follows:——

SIR,—As the Treasury, after a lapse of four years since the first appearance of the translations of M. Zola's novels, has taken upon itself the prosecution instituted for the suppression of these books, I beg leave to submit to your notice some hundreds of Extracts, chiefly from English classics, and to ask you if in the event of M. Zola's novels being pronounced "obscene libels," publishers will be allowed to continue issuing in their present form the plays of Shakespeare, Beaumont and Fletcher, Massinger, and other old dramatists, and the works of Defoe, Dryden, Swift, Prior, Sterne, Fielding, Smollett, and a score of other writers—all containing passages far more objectionable than any that can be picked out from the Zola translations published by me.

I admit that the majority of the works above referred to were written many years ago, still they are largely reprinted at the present day—at times in Éditions de luxe at a guinea per volume, and at others in People's Editions, priced as low as sixpence,—so that while at the period they were written their circulation was comparatively small, of late years it has increased almost a hundred-fold.

So long as the present prosecution was in the hands of the fanatics who initiated "The Maiden Tribute" of "The Pall Mall Gazette," and whose mouthpieces in both Houses of Parliament have gulled the Legislature with cock and bull sensational stories of there being ten houses in a single London street where young girls are accommodated with private rooms and supplied with indecent books for perusal,... so long as the prosecution remained in those hands, I was content to leave the decision to the sound common-sense of an English jury. Now, however, that the Government has thought proper to throw its weight into the scale, with the view of suppressing a class of books which the law has never previously interfered with—otherwise the works I have quoted from could only be issued in secret and circulated by stealth—circumstances are changed, and I ask for my own and other publishers' guidance whether, if Zola's novels are to be interdicted, "Tom Jones" and "Roderick Random," "Moll Flanders" and "The Country Wife," "The Maid's Tragedy" and "The Relapse," in all of which the grossest passages are to be met with will still be allowed to circulate without risk of legal proceedings.

In the Extracts now submitted to your notice, and which you must be well aware could be multiplied almost a hundred-fold, I have made no selections from cheap translations of the classics with their manifold obscenities... nor from popular versions of foreign authors, whose indecency surpasses anything contained in the English versions of "Nana" and "The Soil," and who, unlike M. Zola, exhibit no moral tendency whatever in their writings.

The Temperance cause never before found so potential an advocate as M. Zola proved himself to be in "L'Assommoir." A great writer who has exercised the wide influence on contemporary literature that M. Zola has done, whose works have been rendered into all the principal European languages, and who commands a larger audience than any previous author has ever before secured, is not to be extinguished by having recourse to the old form of legal condemnation, and especially at the bidding of a fanatical party, the disastrous effects of whose agitation on the health of our soldiers is recognised and lamented by all military, and by most sensible, men.

Is life as it really exists—with the vice and degradation current among the lower classes, and the greed, the selfishness, and the sensuality prevalent in the classes above—to be in future ignored by the novelist who, in the case of M. Zola, really holds the historian's pen? Is actual life to be no longer described in fiction, simply because the withdrawal of the veil that shrouds it displays a state of things unadapted to the contemplation—not of grown-up men and women, but of "the young person of fifteen," who has the works of all Mr. Mudie's novelists to feast upon? This certainly was not the law in the days of Defoe, Swift, and Fielding, and it needed a canting age, that can gloat over the filthiest Divorce cases, while pretending to be greatly shocked at M. Zola's bluntness; but above all, it required a weak-kneed Government, with one who was once a literary man himself at its head, [Lord Salisbury] to strain the law in a way that an educated alderman refused to do the other day in reference to Boccaccio's "Decameron."

Time, we are told, brings round its revenges, and the books burnt by the common hangman in one age come to be honoured in the next. England may render itself ridiculous in the eyes of Europe by visiting the works of M. Zola with the same kind of condemnation which the civilised world has accorded to the writings of the degraded Marquis de Sade; still it requires no particular foresight to predict that a couple of generations hence, when the tribe of prejudiced scribes—who, ignorant for the most part of their own country's literature, now join in the hue and cry against M. Zola—are relegated to their proper obscurity, the works of the author of the Rougon-Macquart Family will take rank as classics among the productions of the great writers of the past.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

HENRY VIZETELLY.

The letter was dated September 18, 1888, on which very day the sessions of the Central Criminal Court began, but the Crown applied for a postponement of the trial, and as Vizetelly's counsel, who had been instructed to oppose any postponement, failed to attend, and Vizetelly himself was refused admittance by an officious policeman, the case was at once put off until October. This was very prejudicial to Vizetelly's business, particularly as the attacks of certain prints did not cease. Looking back, it greatly astonishes the writer that no application was ever made to commit the publishers of several London and provincial newspapers for circulating comments on a case which was sub judice, comments well calculated to prevent the defendant from obtaining a fair trial. But that idea does not seem to have occurred either to Vizetelly or to anybody about him. He at first had felt fairly confident respecting the issue of the case, and, as an old journalist, had entertained nothing but contempt for the terriers of the profession who barked at his heels. But his confidence had been shaken by the intervention of the Government and was finally undermined by well-meaning friends who, owing to the postponement of the proceedings, had many an opportunity to tender counsel. Their motives were most honourable and praiseworthy, no doubt. But the effects of their solicitude were disastrous. "In the multitude of counsellors there is wisdom," it has been said, but in Vizetelly's case there came chaos. While some urged him to fight, others begged that he would do no such thing. There was an incessant chassê-croisê of advice; and Vizetelly, now resolving on one course, and now on another, was at last at a loss what to do. Had he been a younger man the case would have been very different, for in his prime he had evinced much energy of disposition, and in difficult moments had relied on his own sound common-sense. But he was now sixty-eight years old, and though he was still of most industrious habits, the strenuous life he had led had left its mark upon him. Moreover, a complaint from which he suffered had taken a very serious turn, and frequent physical suffering was not conducive to perspicuity and energy of mind. Again, there was the position of his business to be considered. In consequence of the prosecution and the misrepresentations of the newspapers, the trade became afraid to handle any books he published, and thus his sales rapidly decreased. Besides, he found it difficult to obtain efficient counsel for his trial. The Parnell Commission was then sitting, and most of the great men of the bar were retained in it. Mr. (now Sir Robert) Finlay, Q. C., who was applied to, could not take the brief, having in hand already a large number, which the barristers engaged before the commission had been obliged to decline. Other men were similarly circumstanced, and there was one who honestly admitted that he did not like the case, and would therefore prove a very poor advocate. Eventually Mr. Francis B. Williams, Q. C., Recorder of Cardiff, was retained, with Mr. A. R. Cluer, now a London police magistrate, as his junior.

Beset as he was by various friends, who held that in the state of public opinion he was not likely to secure an acquittal, Vizetelly at last allowed some inquiries to be made as to what would happen if he pleaded guilty and withdrew the three incriminated Zola translations, such as they were then, from circulation. A letter bearing on this question, says: "If the rest of Zola's works that are open to objection are withdrawn, the Solicitor-general will be content that the defendant be not sentenced to imprisonment. He thinks that the taxed costs of the prosecution should be paid, and will leave the amount of fine (if any) to the judge, not pressing for a heavy one if the defendant is a man of small means." This communication gave a new aspect to the case. The question was no longer one of three of Zola's works, all of them might have to be withdrawn. Private testimony respecting the narrow puritanism animating the authorities at that moment indicated that they would show no fairness in considering the matter of other books by Zola, at least in the form of translations; for it is a fact that while Vizetelly's expurgated English versions were being prosecuted, the French volumes still entered the country and were freely sold there and circulated by libraries! Thus all who knew French were privileged to read Zola verbatim, whereas those who did not know that language were not allowed to peruse expurgated renderings of his books. Under the circumstances set forth above, Vizetelly finally resolved to contest the case; but, unfortunately, the inquiries instituted on his behalf had made his hesitation known to the prosecution and inclined it therefore to vigorous courses.

The trial took place on October 31, 1888, at the Old Bailey, before the Recorder, Sir Thomas Chambers, whose literary bent may be indicated in a few words: his favourite poet was Hannah More. The jury appeared to be of the usual petty-trading class. The prosecution was conducted by the Solicitor-general, then Sir Edward Clarke, who had already made a considerable reputation by certain cross-examinations, and who at a subsequent period defended the unhappy Oscar Wilde, when the latter was convicted of unnatural offences. Sir Edward opened the proceedings at no great length. He first pointed out that, in the case of "The Queen v. Hicklin," Lord Chief Justice Cockburn had ruled that the object for which a publication might be issued had nothing to do with the question of its obscenity, the test of which was whether the matter so published had a tendency to deprave and corrupt those into whose hands the publication might fall. He also mentioned that it had been ruled in the Hicklin case that no excuse was supplied by the circumstance that other literature—especially that of two or three centuries previously—might contain passages conflicting with one's judgment as to what was fit for circulation. Then he passed to "The Soil," asserting that it was full of bestial obscenity, without a spark of literary genius or the expression of an elevated thought. That, of course, was his opinion of the book; and several years later he amused a great many people by giving his opinions on literature at large, thereby arousing the ire of a distinguished writer, Mr. Edmund Gosse, who unfortunately made the mistake of telling Sir Edward Clarke that he was a lawyer and not a littérateur—even as Mr. Chamberlain in his fiscal campaign subsequently reproached Mr. Asquith for discussing business when he was not a business man. But whatever might be Sir Edward Clarke's calling, he had a right to hold opinions on literature and to express them. Even a tinker may have literary views and may make them known, though it does not follow that they will be adopted by the community generally.

Having concluded his address, the Solicitor-general proceeded to read some passages from "The Soil," and he had scarcely begun when a faint stir among the public brought a loud cry of "Silence!" from the ushers. Ernest Vizetelly, who was seated at the solicitors' table, then turned and perceived several French newspaper correspondents and others striving to preserve their gravity, which had been disturbed by the curious manner in which Sir Edward Clarke pronounced the French names confronting him in the pages of "The Soil." For a time one might have imagined he was reading a novel of the kail-yard, for he persistently pronounced "Jean" as if it were a Scottish name. For instance:

"There was a lass, and she was fair,

At kirk and market to be seen;

When a' the fairest maids were met,

The fairest maid was bonnie Jean."[22]

The effect was the more curious as in Zola's book Jean, of course, is a man, whereas from Sir Edward Clarke's pronunciation it might have been inferred that he was a woman! However, the slaughter of French names did not continue long. The jurymen expressed their views clearly enough by interrupting a passage describing how the girl Françoise Mouche brings the cow, La Coliche, to the bull at the farm of La Borderie. The mere idea that such a thing could happen evidently amazed and disgusted them; but their surprise would probably have been less great if, instead of being Londoners, they had been yokels from the country, for, as various correspondents informed the writer subsequent to the trial, instances of the same kind could have been easily adduced from different parts of the United Kingdom, notably Wales.

One of the Pecksniffian arguments at that time was that Zola wrote for his own countrymen, and that even if he were justified in addressing them as he did, there was no excuse for placing translations of his works in the hands of English people, to whom those works did not apply. This was ridiculous, English society being quite as deeply, though by reason of the national hypocrisy, not so openly corrupt as French society. As for the case of Françoise Mouche and the cow, La Coliche, one might have found, as already stated, numerous instances of young girls being similarly employed in Great Britain. But of course such matters were not to be spoken of or written about! They must be cloaked over, covered up, so that they might continue unhindered! Besides, it was abominable to assert such things. The rural districts of England were moral paradises, safe in the guardianship of parson and squire! Only London was immoral, poor, wicked London, which bears the weight of many a sin which is not its own. It would be interesting, indeed, to know how far those moral paradises, the rural districts, contribute to the illegitimate births with which London is at times reproached. Is there even a single day in the year when London does not witness the arrival in its midst of some unfortunate country girls who have left their homes to hide their shame among the multitude of its inhabitants?

But one must return to the trial. When Sir Edward Clarke had read a few of his extracts the demeanour of the jury and their repeated interruptions plainly indicated what their verdict would be. Even then, no doubt, the better course would have been to let the trial proceed, in order that counsel might have his opportunity of presenting the defence, if not for the enlightenment of the jury, at least for that of the public at large. Mere passages,—there were twenty-five, some, no doubt, rather long ones, incriminated in a volume of hundreds of pages—proved nothing. One might find scores and scores of passages in the Bible which if taken without the context and the general knowledge one has of the book might make it appear undesirable. In the case of "The Soil," the facts should have been expounded, whether they influenced the jury or not. But Vizetelly's counsel, Mr. Williams, was evidently quite disheartened; he deemed it useless to prolong the case; and so after the briefest of consultations the plea of "not guilty" was withdrawn for one of "guilty." It was a complete collapse.

Mr. Williams, however, began to address the Recorder in mitigation of punishment, and in doing so referred to Zola as "a great French writer." "Oh, no, a voluminous French writer, if you like," said Sir Edward Clarke. "A popular French writer," the Recorder suggested. "A writer who certainly stands high among the literary men of France," Mr. Williams retorted; whereupon Sir Edward Clarke exclaimed in a pompous way, "Do not malign the literature of France!" Whether the Solicitor-general was qualified to express any opinion of weight on the literature of France might well have been doubted by all who had heard him pronounce the name "Jean." But Mr. Williams got in a last word. Confirming his description of Zola, he said: "It is apparent to all who have studied the literature of France at the present day."[23] And he might have added that Zola had but lately been made a knight of the Legion of Honour for the very book, for having issued an expurgated edition of which Vizetelly was about to be punished. On that subject Sir Edward Clarke stated that he did not ask for imprisonment, and however much one may differ from him, particularly in literary matters, it is essential one should recognise that, having won the day, he showed some forbearance. Vizetelly had naturally pleaded guilty, not only to the indictment respecting "The Soil," but to those respecting "Nana" and "Piping Hot," which were not gone into. The Recorder admonished him and then sentenced him to pay a fine of a hundred pounds and to enter into his recognisances in two hundred pounds to be of good behaviour for twelve months.[24]

But a very important matter has still to be mentioned. A certain undertaking was given in court respecting the Zola translations published by Vizetelly. The present writer, his brothers, and many friends who were present, as well as the defendant himself, distinctly understood that undertaking to be that the three incriminated volumes and all other works by Zola which were as objectionable as those three should be withdrawn from circulation; but it was not said that none of Zola's books should ever be sold. On that point it is advisable to quote the shorthand writers' transcript, which shows how the Solicitor-general interpreted the undertaking: "Sir Edward Clarke: Of course I am very glad that a course has been taken which will not only stop from circulation the three books contained in these indictments, but which carries with it an undertaking by Mr. Vizetelly that he will be no party to the circulation of any other of the works which M. Zola has produced, any others—I should like to say—which are at least as objectionable as those which are indicted before your Lordship to-day."

According to the writer's recollection, and that of his relatives and friends, Mr. Williams in giving the undertaking applied to the incriminated books the expression, "in their present form"; but these words do not appear in the shorthand notes which the writer holds. Nevertheless the language of Sir Edward Clarke suggests that some similar words had been used. It followed that Vizetelly, in all good faith, believed that he was entitled to sell Zola's books if he rendered them unobjectionable by further expurgation. But when other proceedings ensued it was even suggested that he was not entitled to sell them under any circumstances; and he was actually admonished for having inserted in his catalogue the words "Undergoing revision" after the titles of "La Terre" and "Nana." This plainly showed that the real secret desire of the authorities and the "Vigilants" was to suppress translations of Zola altogether. They cared not a jot what Vizetelly might attempt in order to satisfy their narrow puritanism, they were determined to regard all expurgation as inadequate, to pursue and persecute Vizetelly till he abandoned that author altogether. And to effect this they were ready to strain the law as it had never, perhaps, been strained before.

Meantime Zola, who naturally heard of Vizetelly's trial, attached, personally, little importance to it. He held that the English were making themselves ridiculous by setting up a puritanical standard of morality when their own literature contained many examples of outspokenness going far beyond anything that he had ventured upon. Apart from the writers of the past, he had some acquaintance with modern English novels such as had been translated into French, there being various series of that kind;[25] and he took the view that many of them, with the glamour they cast over vice and even their artful reticence, were certainly calculated to demoralise people, whereas his own rough frankness could only give the reader a shock, as indeed it was intended to do. At the same time he was not surprised at the outcry, for there had been one in France, where the ground was far better prepared for outspokenness than in England, where the cant of the Victorian era had ever striven to set restrictions on the novelist's art. Thackeray, we know, had chafed under them, and had written on his preface to "Pendennis": "Even the gentlemen of our age... we cannot show as they are, with the notorious foibles and selfishness of their lives and their education. Since the author of 'Tom Jones' was buried no writer of fiction among us has been permitted to depict to his utmost power a MAN. We must drape him, and give him a certain conventional simper, Society will not tolerate the Natural[26] in our Art."

As for the issue of the affair for the Vizetellys, of whom Zola then knew little, having only had a few business transactions with them, he did not feel deeply affected, for the matter seemed to him to resolve itself into a moderate pecuniary loss which, he imagined, the defendant would be well able to incur, having made considerable profits on the incriminated books.[27] For the rest, when in later years Ernest Vizetelly showed him various newspaper cuttings imputing to him a variety of statements, Zola remarked that some he had never made, while as for others his words had evidently been misconstrued.

As it happened, the affair proved far more serious for Vizetelly & Co. than Zola had thought possible. The firm then had several thousand pounds locked up in illustrated books which were not nearly ready for publication. The sales of its existing books had been declining for several months, so that its receipts had become small, though its expenses remained heavy and it had liabilities such as are always incurred in trade. Under these circumstances it was felt that the Zola translations, being a valuable property, could not be entirely sacrificed. The undertaking given in court was interpreted in the sense previously indicated, and, though the books were absolutely withdrawn for a time, it was decided to put them on the market again after they had been adequately expurgated.

A good deal of this work was entrusted to Ernest Vizetelly, but he was hampered by important restrictions. He learnt that the books were stereotyped and that his alterations must be such as might be effected in the plates, for it would be too expensive to reset the books in their entirety, though a few pages might be reset here and there. Under these conditions, as sentences and paragraphs often had to be struck out or considerably abbreviated, it became very difficult to fill the gaps which occurred. Ernest Vizetelly at least did the best he could. He spent two months on the work and deleted or modified three hundred and twenty-five pages of the fifteen volumes handed to him. Henry Vizetelly was in poor health at the time; but he himself attended to a few volumes, and his son's work was sent to him for inspection before it was forwarded to the printers. Whether he himself went through it in its entirety or not cannot be stated positively; but at all events the work was passed, and some of the Zola volumes were reissued.

Soon afterwards the "National Vigilants," elated by their previous easy victory, returned to the warpath. Henry Vizetelly was again summoned, this time for selling the following books: "The Assommoir," "Germinal," "Fat and Thin" ("Le Ventre de Paris"), "The Rush for the Spoil" ("La Curée"), "Abbé Mouret's Transgression," "How Jolly Life is" ("La Joie de Vivre"), "The Fortune of the Rougons," and "His Excellency E. Rougon," by Zola; "Madame Bovary," by Gustave Flaubert; "A Love Crime," by Paul Bourget; "A Woman's Life" and "A Ladies' Man" ("Bel Ami"), by Guy de Maupassant. At the same time W. M. Thomson, discharged when summoned for "The Decameron," was prosecuted for selling a translation of "The Heptameron," as well as other works, and other booksellers were likewise proceeded against in connection with some of the American versions of Zola's novels. The cases were heard by Mr. Vaughan, a testy old magistrate who long presided at Bow Street, and who committed Vizetelly for trial with respect to the following works: Zola's "Abbé Mouret's Transgression," "The Rush for the Spoil," "Fat and Thin," "His Excellency E. Rougon," "How Jolly Life is"; Bourget's "Love Crime" and Maupassant's "Ladies' Man." A few objections had been raised in the press apropos of the prosecution of "Madame Bovary," and with the gracious approval of the great Stead of the "Maiden Tribute," the summons respecting that work was eventually adjourned sine die.[28]

When Vizetelly returned to his office from Bow Street on the day of his committal, he took the only course consistent with integrity. He assigned everything he possessed for the benefit of his creditors, in order that his business might be liquidated. It was impossible to carry it on any longer. The wreckers had resolved to ruin him, and had succeeded to their hearts' desire. Friends came and expressed their sympathy—among others, Sir Henry Irving, the late Sir John Gilbert, and Mr. Birket Foster—but there was virtually no opportunity for any public protest. Not a newspaper now dared to print a word on behalf of this old servant of the press whom the "Vigilants" had chosen for their victim. On the morrow of the first trial the "leader" writers had hastened to avail themselves of his plea of guilty to pass unanimous condemnation on him. The delighted "Vigilants" had promptly printed and circulated extracts from the "Times," "St. James's Gazette," "Whitehall Review," "Star," "Globe," "Morning Advertiser," "Saturday Review," "Methodist Times," "Liverpool Mercury," and "Western Morning News"; and those samples of English press opinion might have been multiplied indefinitely. They showed all parties in agreement: the Tories and the Radicals, the Puritans and the Publicans. Coote, the secretary to the "Vigilants," had become censor morum, and all bowed to his authority. Yet some members of this so-called "National Vigilance Association" had been mixed up in various nefarious matters. There had been, as Mr. George Moore subsequently wrote, "the case of an unfortunate foreign prince, who was dragged into court on a charge of abduction or seduction, or both; when the matter came to be sifted it was found that he was absolutely and wholly innocent. So conclusive and so unimpeachable was the evidence, that Mr. Besley, who prosecuted for the Association, had to admit that he had nothing to say, and the judge replied, 'I should think not, indeed.'"[29]

Again there was a notorious Leamington case in which the "Vigilants" prosecuted, and in which, as Mr. Moore again pointed out, it was proved that two women clandestinely took an innocent girl from her employment, plied her with filthy questions, threatened her, and induced her to sign a paper which might have led to a boy of fifteen being sent to prison for two years![30]

And this was the class of person that assumed the prerogative of Literary Censorship. The press prostrated itself before the new Terror, and the Government supported it by again taking up the prosecution of Vizetelly. The trustees of his estate resolved to fight the case and provided funds for that purpose, but while the selection of counsel was in abeyance, Mr. Frank Harris, then editor of "The Fortnightly Review," and one of the few who realised that an odious tyranny was being established, generously offered to bear all Vizetelly's expenses. Mr. Harris desired, however, that the defence should now be entrusted entirely to Mr. Cluer, who had acted as Vizetelly's junior counsel at the first trial, and who had also appeared for him at the recent police court proceedings. There were various advantages in such a course. Mr. Cluer's knowledge of the French language was perfect; he had read Zola's works in the original, and he knew with what a lofty purpose Zola wrote. The present writer favoured the suggested arrangement, but he had no power in the matter. Any suggestions he made were invariably set aside throughout the affair, on the ground that he had not been long resident in England, that there were many things which he did not properly understand, and so forth. There was some truth, no doubt, in those objections; but it often happens that a person who stands a little apart from a battle has a clearer perception of its chances than those who are actually engaged in it. The writer feared that a fresh conviction was virtually inevitable, but he also felt that Mr. Cluer would do his best for his client, and that the ship, though it might well go down, would then at least do so with colours flying. But it was held imperative that a Queen's Counsel must be engaged, for it would be ridiculous to pit a stuff-gownsman against the Solicitor-general! And so, after various delays and difficulties, as on the former occasion, the late Mr. Cock, Q. C., was retained, Mr. Cluer again being secured as junior counsel.

Henry Vizetelly and his trustees were still resolved to fight the case, after their own fashion; and by way of answering any charge of having broken the previous undertaking it was proposed that Ernest Vizetelly should give evidence respecting the recent expurgation of Zola's books. His father inquiring if he were prepared to do so, he immediately assented. He went further: he agreed to take, so far as the Zola volumes were concerned, at least the odium of this second affair on himself by assuming responsibility for what had been done. It was impossible for him to hesitate,—no son would hesitate to shield his father as far as might be possible,[31]—but now that the time has come to write of these matters he owes it to himself, and particularly to his children, to point out that the responsibility which he assumed was not really his. The expurgatory work he had accomplished had been limited by the conditions imposed on him; within them he had done his best; but, even then, he had submitted his work for approval, saying: "This is all I can do. If anything further is required another must do it." He knows, by the "proof" slips in his possession, that a few further alterations were made in his work, the bulk of which, however, was passed, and sent to the printers. He was not surprised by that, and would not be surprised by it now, for he holds that the alterations he made were sufficient to satisfy everybody except fanatical Puritans. At the same time, in that hour of frenzied cant and unscrupulous injustice the responsibility he assumed was no light one, for even though he could not be proceeded against at law, the odium attaching to it might be very prejudicial to him. And while he had a wife and children to support, he had no interest in his father's business beyond being its paid servant; he knew that it had been established for the benefit of his younger brothers; which consideration had largely deterred him from pressing his own advice during the affair, for he did not wish to be accused of attempting to supplant anybody. If, to-day, he has pointed out the actual circumstances it is because he does not wish anybody to believe, as many have inferred for years, that his father's ruin and imprisonment proceeded from any neglect of his. It is true he has long allowed that to be thought,—it might be assumed from the account of his father in the "Dictionary of National Biography,"—but the facts were really such as have been stated here.

Vizetelly & Co. intending to fight the case, as soon as the amount of Mr. Cock's fee had been ascertained it was voluntarily increased to a larger one in order to induce him to do his utmost. An attempt was made to arrange a consultation some days before the trial, but as a matter of fact Mr. Cock was not seen until about half an hour before the case opened at the Central Criminal Court, on May 30, 1889. Ernest Vizetelly accompanied his father, who was now in very bad health indeed. Mr. Cluer introduced them to Mr. Cock, and a conversation took place in a room adjoining the robing room at the Old Bailey. At the first words, Mr. Cock declared there could be no defence. He did not pause to argue. It was plain he wished to dispose of the case as quickly as possible. The defendant, said he, must throw himself on the mercy of the court, that was the only thing to do. Henry Vizetelly, who had come to the Old Bailey expecting something very different, was overwhelmed by this intimation. The blow was a coup de massue for him, and at first he could say nothing. His son, likewise very much amazed, and, in particular, disgusted with this blustering barrister who threw up the sponge at the moment of going into court, tried to interject a few words, but was curtly silenced. There was nothing, nothing to be done, so Cock, Q. C., repeated. Under the circumstances he might have returned the extra fee which had been sent him to induce him to make a good fight, but he never did. There was, however, one course that he was willing to take when he saw the distress of his ailing old client. He offered to ascertain what would be the result of a plea of "guilty." To Vizetelly's son that seemed a strange course to pursue. He did not like hanky-panky or aught suggestive of it. However, Mr. Cock rose—he was a fat, unwieldy man, with a startling red face—and rolled out of the room. Whom did he actually see? The writer is not certain, and in a case of uncertainty it is best to stay one's pen. But when Mr. Cock returned he said in presence of the defendant, his son, and Mr. Cluer, that the Solicitor-general was not leniently inclined and that Vizetelly's recognisances "to be of good behaviour" would have to be estreated; while the Recorder, Sir Thomas Chambers, held that there must be some imprisonment. Did Henry Vizetelly hear those last words? According to his own account, afterwards, he never did; for had he done so, in spite of all Mr. Cock's bluster, he would never, he said, have pleaded guilty. But the poor man may well have misunderstood his counsel. He was in a condition little short of actual physical collapse. In a dreamy way, as it were, he gave, or seemed to give, a feeble assent to everything. Had there been time, his son would have made an effort to reopen the question, for it occurred to him that, even then, one might perhaps have dispensed with Mr. Cock's services and have induced Mr. Cluer to undertake the defence unaided. But there was no opportunity for further deliberation; the court was almost waiting, and one went downstairs to meet the inevitable.

The proceedings were brief. Vizetelly took his stand at the foot of the solicitors' table, his son who sat there, and who at every moment feared to see him fall, holding his hand the while. For an instant, when challenged, he hesitated, then ejaculated the word "guilty," much as if he were expectorating.

Thus the case was never argued on its merits. Of course the Solicitor-general held that the previous undertaking had been violated, and asked that the defendant's recognisances in two hundred pounds should be estreated. Then Mr. Cock spoke of the expurgation of the books, which in his opinion "had not gone sufficiently far," and added that the defendant was in his seventieth year and in very delicate health. On that point Ernest Vizetelly testified on oath that his father had suffered for some years from a complaint which had lately assumed a very serious character and necessitated the constant employment of surgical instruments. He then imagined his examination to be over, and was about to leave the witness-box when Sir Edward Clarke inquired if he were a member of the firm of Vizetelly & Co. The witness answered in the negative, he was a journalist by profession, and if previously employed by the firm he had then ceased to be so. But the Solicitor-general pressed him for the purpose, so it seemed, of extracting some undertaking with respect to the future sale of Zola's works or the destruction of the existing stock. This the witness had no power to give, and he was determined to say nothing that might lead to it being given by others. As the pertinacity of counsel continued, the witness, feeling somewhat ruffled, could not refrain from retorting: "You have made the defendant a pauper! What more do you want?" "Now, now," Sir Edward Clarke shouted back, "we want none of that!" "Well, I have nothing else to say," the witness added. "I do not belong to the firm of Vizetelly & Co., and I now know nothing about it." Thereupon the Solicitor-general, somewhat discomfited, had to let him go.

The Recorder then passed sentence. It was useless, he said, to fine the defendant, as he had no means to pay a fine. But his recognisances must be estreated, and he must go to prison, as a first-class misdemeanant, for three months. Vizetelly was at once led below; and his son applied, through counsel, for leave to speak with him before he was removed to jail. The Recorder granted permission, but the son was not allowed to follow his father. He and Mr. Lickfold (Vizetelly's solicitor) were told to apply at the small barred gate of Newgate, immediately adjoining the Old Bailey. They went thither and were admitted. A warder, or attendant, was told of the permission the judge had given, and went to make inquiries. Mr. Lickfold retired, and the writer remained waiting. Presently the attendant returned and said to him: "The Governor's answer is that you cannot see the prisoner. The judge has no power to give leave to see any prisoner when once he has left the court." It was useless to expostulate. Ernest Vizetelly could only withdraw, in considerable distress, for he knew that his father in the state of his health would require prompt attention and relief; and he had been anxious to do what he could in that and other matters.[32]

However, he met his brothers, and various arrangements were made to provide for their father's comfort. As the case was to have been fought, there had been no anticipation that it would end that same day, and nothing was actually ready. At last, Holloway being the jail where first-class misdemeanants are usually lodged, application was made there; but the officials knew nothing whatever of Vizetelly, he had not been sent to them. After some discussion Ernest and his brother Frank Vizetelly, proceeded to Pentonville, where they were received very courteously by the deputy governor, who said to them: "Yes, your father is here. Why he was sent I do not know, we have no accommodation for first-class misdemeanants. None has ever been sent here before. Your father is in a shocking state, he had been suffering for hours when he arrived here; I have placed him temporarily in our infirmary. I telegraphed to the Prison Commissioners but have had no answer. You should go to them at once at Whitehall, and ask them to remove him to Holloway."

This was done. The facts were set out in writing and sent in to some of the Commissioners, who, after an interval of an hour or so, received Frank Vizetelly, and airily told him that there was no mistake at all, that his father had been sent to Holloway and would be found there! The fact is that, while the sons were waiting, telegraphic instructions had been sent to Pentonville for Vizetelly's removal. That could not be effected in an instant on account of his serious condition, but when he was lodged in the infirmary at Holloway the Commissioners felt they were safe from any charge of neglect. Ernest Vizetelly, however, was not disposed to let the matter drop, and having drafted a question for the Home Secretary (Mr. Matthews) he wrote to Mr. Labouchere, M. P., to inquire if he would ask it in the House of Commons. He received the following characteristic reply:

Dear Sir,—I do not think that the clerks at the table would accept the question as written, for it enters too fully into details. However, be this as it may, I should not be the proper person to ask it, for I have had many actions for libels, and it would be thought that I had an eye to my future accommodation. As a matter of tactics, I should advise that no question be asked, for the only person who can reduce the sentence is the Home Secretary. I do not know if he will, but he certainly will not if his hack be put up.—Yours faithfully,

H. LABOUCHERE.

24 Grosvenor Gardens, S. W.

June 1. [1889].

Mr. Labouchere's advice was certainly good, and it was followed. That is why the facts have never been disclosed till now.

Little more need be added here. Henry Vizetelly left a long account of his prison experiences which the writer may some day print. He was fairly well treated at Holloway,[33] but he writes that after he had left the infirmary (of which he was long an inmate, as the result of the neglect in which he was left immediately after his trial) he had great difficulty in obtaining water of the requisite heat for the treatment of his complaint, his room (previously occupied by Edmund Yates) being so far from the kitchens that, as a rule, the water was almost cold by the time it reached him. His health naturally deteriorated in confinement, but he did his best to look at things cheerfully, and found occupation in planning various literary enterprises. Several friends, notably Edmund Yates, showed great kindness at this time. Mr. George Moore did his best to ventilate the whole question of the prosecution and Robert Buchanan wrote an able pamphlet under the grim title of "On Descending into Hell." Ernest Vizetelly was then chiefly occupied in preparing and circulating a memorial to the Home Secretary, praying for his father's release on various grounds. Though two or three of the newspapers were already beginning to think that matters had been carried too far, few journalists, unless friends, were asked for their signatures; but Vizetelly's son had the satisfaction of securing the support of several notable authors with whom he had never previously held communication. Their letters of sympathy touched him deeply, and showed him that though the newspaper press might be so largely under the thumb of the "National Vigilants," there were men of letters of high standing who retained all their independence of thought. A few, it is true, made certain reserves with respect to Zola's works, but all felt that Henry Vizetelly ought not to have been treated so harshly. The writer, unfortunately, has preserved no complete list of those who signed the petition (from one hundred to one hundred and fifty in number), and he must apologise for the many omissions in the one that follows. It will be noticed that it contains the names of half a dozen lady writers, as well as those of some prominent artists, who remembered Vizetelly's work as a wood-engraver, and all he had done for the pictorial press:

"Sir Algernon Borthwick (now Lord Glenesk), M. P., Sir E. W. Watkin, M. P., T. P. O'Connor, M. P., Samuel Storey, M. P., Charles Bradlaugh, M. P., Dr. C. Cameron, M. P., The Earl of Desart, Sir J. E. Millais, R. A., Sir John Gilbert, R. A., W P. Frith, R. A., Birket Foster, Linley Sambourne, Harry Furniss, George du Maurier, Prof. Henry Morley, Prof. Geddes, J. Arthur Thomson, Edmund Gosse, Dr. R. Garnett, Dr. F. J. Furnivall, Oscar Browning, John Addington Symonds, Leslie Stephen, Dr. R. Maitland Coffin, Norman Maccoll, James S. Cotton, St. Loe Strachey, Hon. Roden Noel, Havelock Ellis, Robert Buchanan, Walter Besant, Hon. Lewis Wingfield, Thomas Hardy, George Moore, W. Clark Russell, H. Rider Haggard, Hall Caine, 'Ouida,' Mrs. Frances Hodgson Burnett, Mrs. E. Lynn Linton, Mrs. Mona Caird, 'John Strange Winter,' Olive Schreiner, Mabel Collins, Harriett Jay, G. A. Sala, Edmund Yates, Frank Harris, Archibald Forbes, H. W. Lucy, H. D. Traill, A. W. Pinero, William Archer, Augustus Harris, Sir Henry Irving, Henry Arthur Jones, Fitzgerald Molloy, Ernest Rhys, S. W. Orson, Hon. F. C. Lawley, H. Sutherland Edwards, J. C. Parkinson, D. L., Arthur Symons, Alex. C. Ewald, W. R. S. Ralston, Max O'Rell, Savile Clarke, Brinsley Nicholson, G. Laurence Gomme, Frank A. Marshall, Grant Allen, Frederick and James Greenwood, G. B. Le Fanu, F. C. Philips, William Sharp, C. N. Williamson, William Senior, H. T. Wharton, Julius Mayhew, W. H. Dircks, Frank T. Marzials, W. Faux, of W. H. Smith & Sons."

Various persons in official positions, whom etiquette prevented from signing the memorial—for instance Lord Lytton ("Owen Meredith"), then British Ambassador in Paris,—conveyed privately to Ernest Vizetelly their hope that it might prove successful, but the only response of the Home Secretary was that he could not advise her Majesty to interfere in the case. Thus Vizetelly completed his "time" at Holloway, being released at the end of August, 1889. He returned to his home at Putney, and afterwards removed with his daughter and his son Arthur to Heatherlands, near Tilford, Surrey, where he spent, in suffering, the few years that were left him. They happily sufficed for him to see in England a considerable revulsion of feeling with respect to Émile Zola—of whom he had prophesied, in his letter to Sir A. K. Stephenson, that time would bring round its revenges. It will be necessary to allude to him hereafter in connection with Zola's first stay in London, but here one need only add that he died on January 1, 1894, after a final distressing illness. And the little graveyard of the village of Churt became the last resting-place of the man who was persecuted by the Pecksniffs of Great Britain, and whom the "Dictionary of National Biography" describes as the pioneer of the world's pictorial press.