Monique Bournot-Trites

University of British Columbia

1. Introduction

The Canadian Language Benchmarks (CLB) (CIC and CCLB 2012a) and the Niveaux de competence linguistique canadiens (NCLC) (CIC and CCLB 2012b) are

language scales implemented by the Ministry of Immigration mainly for assessing the official language competency level of adult immigrants. However, these language scales are also used in

teaching official languages and for other purposes related to language teaching and learning (see Introduction). In this chapter, I use the development of three

documents – the common theoretical framework (Bournot-Trites et al. 2015), the CLB scale, and the NCLC scale – to illustrate how the Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks (CCLB)

develops guides and tools related to official-language learning and assessment based on research. I first review design-based research (Brown 1992, Collins 1992, Collins, Joseph, and Bielaczyc

2004), which was the method used to establish the theoretical framework and the benchmarks themselves. After acknowledging the origins of design-based research, I describe its characteristics,

and then show how the theoretical framework and the benchmarks were developed and validated following this method. Finally, I conclude with the benefits of using this methodology in the field

of second-language teaching, learning, and assessment.

2. Design-Based Research

Definition

Design-based research, or “Design Experiment” as it was called in its beginnings, is a relatively new methodology born out of the work of Ann Brown (1992) and Alan Collins (1992).

When working in early-childhood classrooms, Brown found that the traditional experimental research was not entirely adequate. She noticed that collaboration with teachers was very important to

inform her research; in fact, just as important as theories and published empirical research. Indeed, traditional empirical research starts with establishing hypotheses based on theories and

previous empirical research related to the questions for which the researcher wants answers. Then experiments are conducted to test the stated hypotheses, and the data obtained are analysed.

Results of the analyses give answers to the research questions, which in turn leads to refinement of the theories. Finally, the practitioners apply the new findings when they are disseminated;

that is, if they find about them, which is not always the case.

Unlike traditional empirical research, design-based research involves practitioners right from the start of the investigation. According to the definition proposed by Wang and Hannafin (2005,

6), design-based research has “a systematic but flexible methodology aimed to improve educational practices through iterative analysis, design, development, and implementation, based on

collaboration among researchers and practitioners in real-world settings, and leading to contextually sensitive design principles and theories.”

Based on the literature, the same authors (Wang and Hannafin 2005, 7) list five important characteristics of design-based research:

(a) pragmatic;

(b) grounded;

(c) interactive, iterative, and flexible;

(d) integrative; and

(e) contextual.

First, design-based research is pragmatic, because the goal is to answer real-world questions by actually designing and creating products or interventions, as well as by adding to theories. As

Cobb, Confrey, diSessa, Lehrer, and Shauble (2003, 10) wrote about design-based research in their conclusion, theories “do real work” in the field, as they bring important

improvements in education. Problems or questions studied through design-based research are real problems found in education contexts.

Second, design-based research is said to be grounded in both theory and practice. It is “a commitment to theory construction and explanation while solving real-world problems”

(Reeves, Herrington, and Oliver 2005, 103). Often, research questions come from needs in the field. Then, researchers choose a theory best suited to the question and find gaps in the related

research literature. For example, if teachers wanted to provide support to readers who have difficulties in the primary years and if they wanted, at the same time, to give some leadership

experience to their older students, they could discuss possible solutions with researchers. Then researchers would look at research done in peer tutoring and see which theoretical framework

would be the best fit to the question, what research had already been done on the topic, and what the gaps were so they could propose interventions. Then they would work with the teachers to

formulate research questions in order to solve the problem and at the same time advance reading theory. On one hand, the theoretical side of the process is important because without the theory

such an endeavour would only result in the evaluation of the intervention or the program put in place and would not lead to theory development. On the other hand, it can be said that theory

gets valued to the extent that it can be shown to improve practice, so it is important to have both researchers and practitioners working together before implementing a new product or

intervention. Furthermore, design-based research is grounded in the natural context of the real world, where not all variables can be controlled for, as could be the case in the artificial

setting of a laboratory. However, the results of design-based research are more directly and easily applicable to the real world than pure laboratory research.

Third, the design process in design-based research is interactive, iterative, and flexible. Collaboration between researchers and practitioners in a complementary fashion is essential so that

the perspectives, knowledge, and expertise of each group can contribute to the benefit of the design. Therefore, there is a need for interaction between the two groups in a repetitive or

iterative manner until the questions and interventions are agreed upon by all consensually. Hence, design-based research is not imposed on practitioners by researchers and some flexibility is

necessary to allow room for changes reflecting the perspectives of all members of the group to be represented in the final decisions.

Fourth, design-based research needs to be integrative, by drawing on different research methods that correspond to different needs. Mixed methods, including questionnaires, interviews, expert

reviews, case studies, and comparative analysis using testing have the ability to answer a multitude of research questions. Anderson and Shattuck (2012), who reviewed the research methods used

in design-based research, indicated: “DBR [design-based research] is largely agnostic when it comes to epistemological challenges to the choice of methodologies used and typically

involves mixed methods using a variety of research tools and techniques” (17).

Finally, design-based research is contextual, that is “given the assumption that comparable performance is most likely in similar settings, contextually relevant design principles and

knowledge are important for design-based researchers” (Wang and Hannafin 2005, 12). Consequently, careful notes have to be kept on the context in which the results were obtained,

including the design process and the setting of the research. That way, other researchers or practitioners are able to examine the results in the light of their own context and needs.

Implementing design-based research

A list of steps are recommended (Jacobsen 2014, Reeves, Herrington, and Oliver 2005) when implementing a design-based research.

The first phase of the research project includes analysis and exploration. Initially, a meaningful problem, in particular a problem identified in the field by learners, educators, or other

people, puts the research project in motion. Then researchers and practitioners meet and collaborate from the beginning to the end of the research project. For this to work, a well-founded

theory related to the real-word problem must be chosen to guide the project.

In the second phase, the design and construction of the implementation takes place. A literature review and a needs analysis are conducted to find the gaps in empirical research published on

the topic and to generate the research questions. Based on the findings from the research questions, an intervention or a product is designed, as well as a plan of evaluation.

The third and final phase is concerned with evaluation and reflection. The implementation is tried out in the context where the problem was identified. Then it is tested and refined continually

in an iterative process until everyone is satisfied. At that point, the impact of the intervention is evaluated in a formative way, which may change the characteristics and details of the

intervention during several cycles, as well as affecting the theories that explain the findings. Ultimately, the design-based research is reported in different ways, first in a series of

interim reports and then in journal articles or books, as more adjustments are made over time for continual improvements.

Summary

Design-based research emerged as a way to address the lack of context in laboratory experiments and in response to a motivation to solve real-world problems, and represents a significant new

way of doing research in educational contexts. Indeed, as Collins, Joseph and Bielaczyc (2004, 21) assert: “They [design-based projects] fill a niche in the array of experimental methods

that is needed to improve educational practices.” After a little more than twenty-five years, this new methodology has been shown to present some challenges (Dede 2004). For example,

Brown (1992) herself has noted that very large amounts of data were collected within designed-based research, generating higher costs in terms of time and money. In fact, Brown notes that the

researchers often lacked enough time to score all the data or store them. Another limitation of this methodology is that with the iterative nature of the research, it may also prove difficult

to know when to stop collecting data and adjusting the final results. Moreover, O’Donnell (2004) indicates that, with continuous adjustments, generalization of the findings may be

challenging because it is difficult to identify which factors are influencing success. However, these challenges can be overcome if the project participants agree to avoid the trap of

collecting too much data, and to limit the number of changes and improvements. Furthermore, a detailed description of the context could improve generalizability by guiding those who want to

apply the findings to another context. Many benefits can be derived from using design-based research. This new methodology has reduced the gap between theory and practice, as well as between

researchers and practitioners. In addition, when practitioners are involved in the research, they are more willing to endorse new tools or approaches and to disseminate them among their

colleagues. Additionally, as Barab and Squire (2004, 2) affirm, “Such design research offers several benefits: research results that consider the role of social context and have better

potential for influencing educational practice, tangible products, and programs that can be adopted elsewhere; and research results that are validated through the consequences of their use,

providing consequential evidence or validity (Messick, 1992).”1

Consequential evidence or validity is of great significance when creating a language framework as the basis for measuring the language competence level of immigrants. It was one more reason for

using this methodology when developing the theoretical framework as well as the CLB and NCLC scales.

3. Development of the Common Theoretical Framework and the CLB/NCLC Scales

As will be shown in this section, the CCLB works with real-world questions and, in general, its actions are grounded in theory and practice. Indeed, for any new endeavour undertaken by the

Centre, the design process is interactive, iterative, and flexible, and mixed methods are used to answer questions. Finally, in a country with two official languages and a diversity of settings

due to the geographical extent, context has to be taken into account during any research process. For example, a geographical representation of practitioners from different parts of the country

and from the two official-languages groups during the various consultation stages is essential. In the same way, in the case of the common theoretical framework and the CLB and NCLC scales,

detailed reports show how those tools were developed and how the validation process was conducted.

In this section, I describe how the theoretical framework and the CLB and NCLC scales were developed following the design-based research principles, where researchers and practitioners worked

together to improve the theoretical framework and the scales.

Right from the start, the development of the common theoretical framework and the CLB and NCLC has been interactive, iterative, and flexible. Indeed, “When CIC (Citizenship and

Immigration Canada) introduced the CLB Working Document (Canadian Language Benchmarks: English as a Second Language for Adults called Working Document) in 1996, the department

made a commitment to revisit the document regularly to maintain its integrity and relevance, to address gaps and to enhance its accessibility” (Bournot-Trites et al. 2015, 7).

Furthermore, revisions led by the CCLB were always dictated by real-world needs, following consultation with stakeholders. The Centre continuously works in partnership with various Canadian

sectors involved in teaching the official languages to adult immigrants, from ministries at the federal level to provincial departments or ministries, colleges, school boards, and

language-teaching associations (see Introduction). Indeed, in the first year following its creation, the CCLB was already seeking the input of its clients to

guide future endeavours. Again in 2008, another massive consultation was conducted, leading to the revision of the Canadian Language Benchmarks: “More than 1,300 people,

representing multiple stakeholder groups, participated in the process.” (Bournot-Trites et al. 2015, 8). At the same time, key stakeholders of the French as a second language community

met to discuss the findings of the consultation and to make recommendations for the French scales. Many recommendations were made with different levels of urgency (see Bournot-Trites et al.

2015, 8–9, for a list of recommendations for the CLB and for the NCLC).

Thus, in 2010, the CCLB produced two new working documents related to the French and English scales: the Canadian Language Benchmarks, Working Document, based on the Canadian

Language Benchmarks 2000: English as a Second Language for Adults (Pawlikowska-Smith 2000) and the Niveaux de competence linguistique canadiens, Document de travail (Sarrazin

2010), which included an updated French theoretical framework. However, the theoretical framework for the English benchmarks, Canadian Language Benchmarks 2000: Theoretical Framework

(Pawlikowska-Smith 2002), upon which the original French framework was based, had not been revised at this time. For historical reasons, the French and English documents had not evolved in a

synchronous way and were not analogous – for more details on the history of the CLB and NCLC, see the introduction chapter of Theoretical Framework for the CLB and NCLC

(Bournot-Trites et al. 2015).

In 2010, the CCLB was set to answer the needs of the stakeholders about the English and the French scales. In order to be acceptable and recognized, the CLB and the NCLC had to undergo a

validation study. The details of the validation process reported in this chapter have been described in unpublished reports (Bournot-Trites and Barbour 2012, Elson 2012a, 2012b).

Before beginning the validation study, the CCLB had asked a pan-Canadian team of experts in second-language learning and assessment to propose a detailed process in order to give direction to

the validation study. It was then decided to create a common theoretical framework as a foundation for both the English and French scales, as well as a process to establish the construct

validity and content validity of the CLB and NCLC. The following sections offer a description of the three phases of the validation study, showing how this process followed the main principles

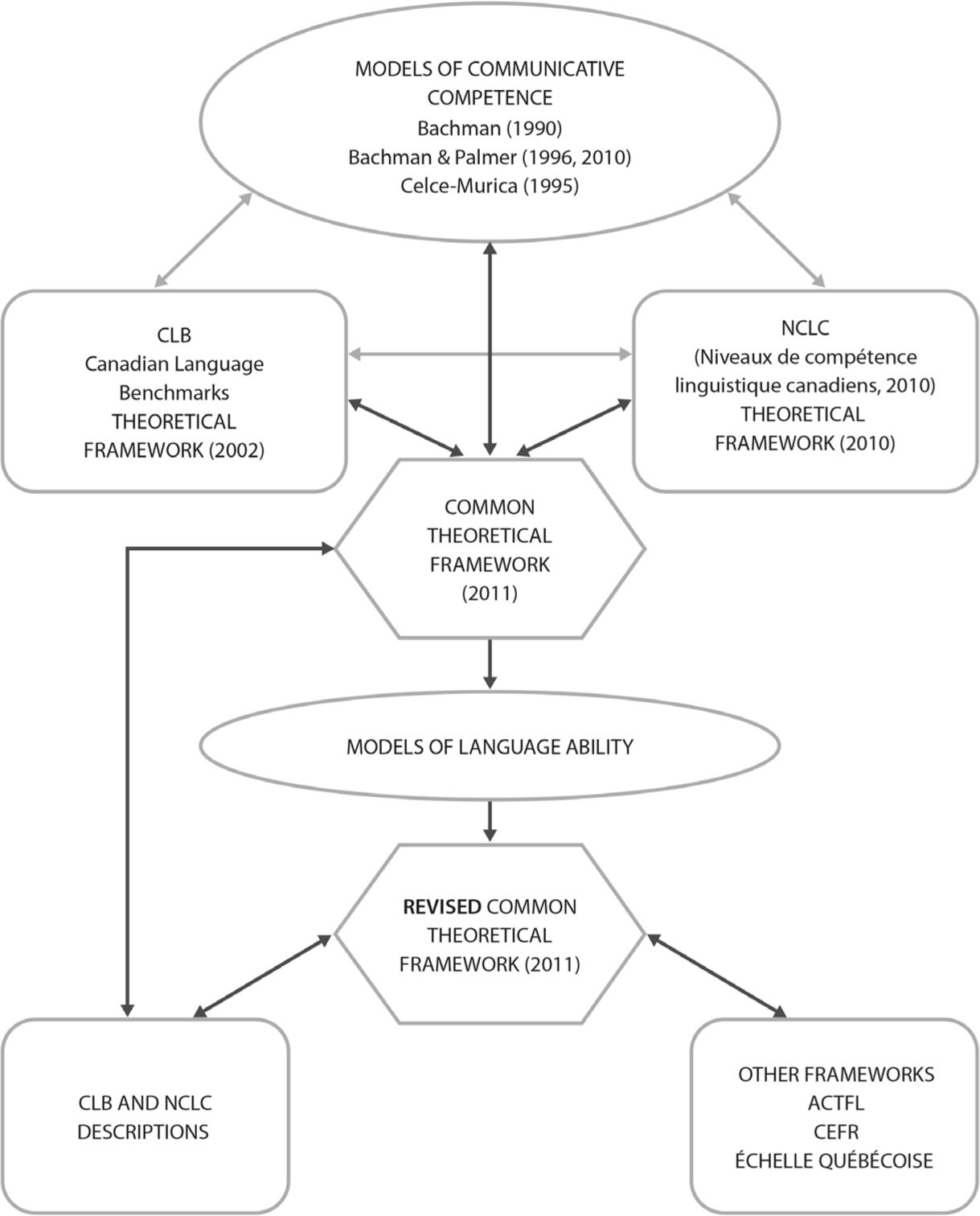

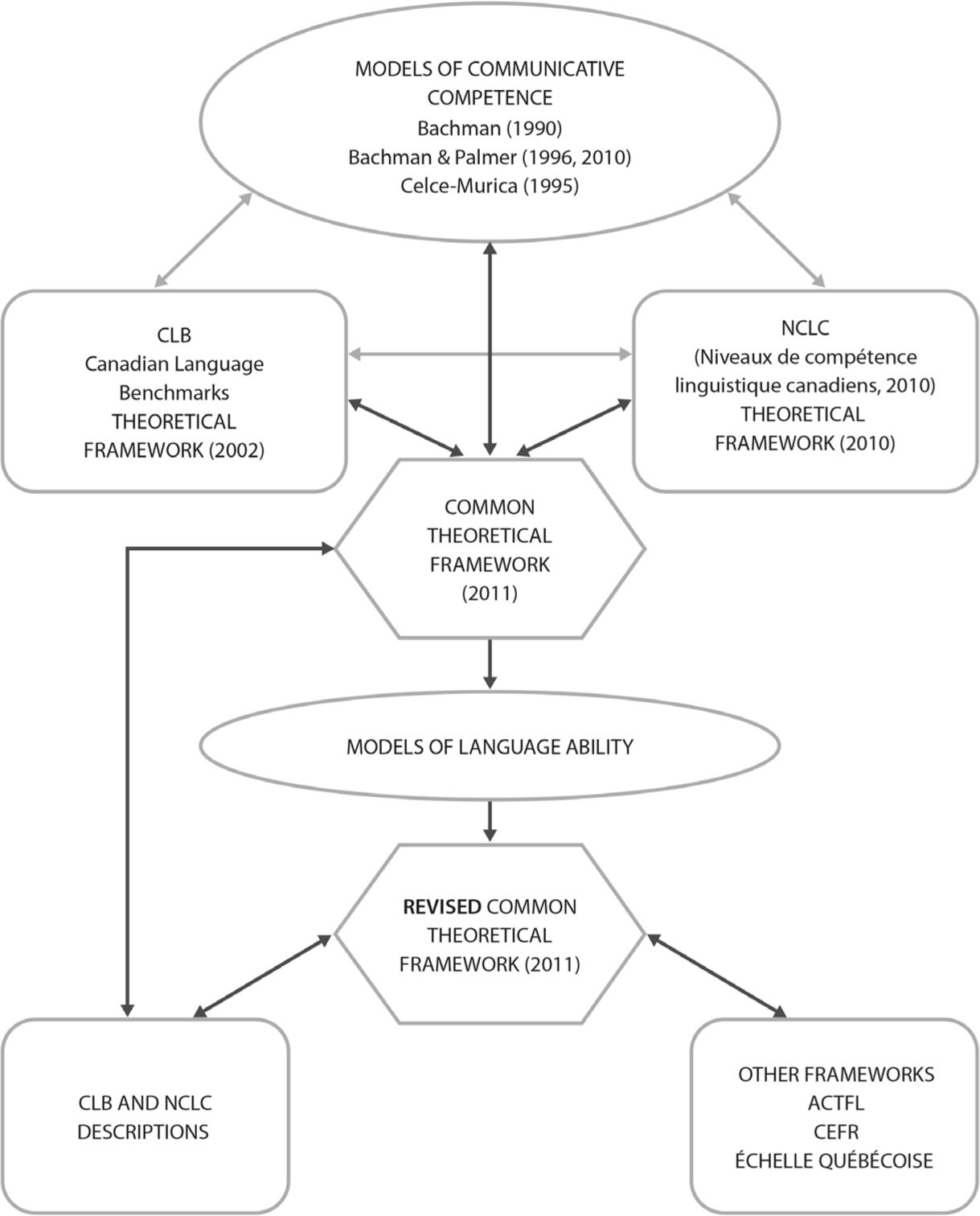

of design-based research. Figure 2.1 represents the validation process for Phases I and II.

Phase I: A common theoretical framework grounded in theory

During Phase I of the validation study, the primary objective was to establish the theory underpinning the CLB and NCLC, and to develop a common theoretical framework (CTF) for the CLB and NCLC

working documents that were revised in 2010 (based on the previous French and English documents). The secondary objective was to verify how well the new common theoretical framework

corresponded to the theories on which it was based. Both the joint project leads, as well as contributing researchers, reviewed, in detail, the CLB and the NCLC – that is the Canadian

Language Benchmarks 2000: Theoretical Framework (Pawlikowska-Smith 2002) and the Niveaux de competence linguistique canadiens, Document de travail (Sarrazin 2010) – to

identify the similarities and differences between them. After a careful comparison and synthesis of the theoretical concepts found in the two documents, a list of the core common concepts was

established.

When writing the first draft of the common theoretical framework (CTF), the theories and research cited in each source document, as well as field studies in English as a second language (ESL)

and French as a second language (FSL), were considered in order to improve the content of the original documents. Additionally, this first draft was validated by experts to make sure that the

new theoretical framework faithfully represented the original documents and the theoretical concepts underlying them. Four experts were selected to undertake this validation, according to

following criteria: they had to be specialists in language assessment, applied linguistics, or curriculum design; hold a Ph.D.; have done research in language assessment or applied linguistics;

and have a basic knowledge of and experience with the CLB or the NCLC. Those experts had to answer a detailed questionnaire asking them to compare the first draft of the Common Theoretical

Framework with the two source documents and with the theories on which they were based: the models of Bachman (1990), Bachman and Palmer (1996), and Celce-Murcia, Dörnyei, and

Thurrell (1995), and on the 2010 updated model of Bachman and Palmer. Considering all these theories created difficulties, because the different models of Bachman (1990), Bachman and Palmer

(1996, 2010), and Celce-Murcia et al. (1995), as well as the CLB and NCLC frameworks, had used different terms to discuss the same concepts. Therefore, to prevent confusion, the lead

researchers created a concordance table (Bournot-Trites et al. 2015, 19 and Appendix A) to show the correspondence between labels and concepts. This essential step of the validation study shows

that the work of the CCLB is grounded in theory, as described earlier in reference to design-based research.

Figure 2.1: Diagram representing Phases I and II of the validation process of the CLB and NCLC

(Double arrows indicate a comparison. Dark arrows indicate verification done by independent experts.)

Source: Bournot-Trites, M. and R. Barbour. (2012) “Unpublished Report on Phases I and II of the Validation of the Canadian Language Benchmarks and Niveaux de Compétence

Linguistique Canadiens.” (reproduced with permission of the authors and CCLB)

From the results of the questionnaire answered by the experts, it was found that both theoretical frameworks were in step with the communicative approach (Germain 1991, Littlewood 1981) and

with the functional approach (Halliday and Kirkwood 1974) to language use, and both were based on the three models: Bachman (1990), Bachman and Palmer (1996), and Celce-Murcia et al. (1995).

Importantly, the model proposed by Celce-Murcia et al. was the primary focal point of both theoretical frameworks. As a next step, the project leads and the contributing researchers, along with

CCLB staff, identified the strongest contributions from each theoretical framework and used the results to develop general guidelines for teaching and assessment that would be applicable to ESL

and FSL. In addition, over the course of the validation activities, the expert panel determined that the updated Bachman and Palmer (2010) model, which was very similar to the 1996 one, should

be given more importance than the Celce-Murcia et al. model, because it was more encompassing. Indeed, it was applicable to all instances of language use rather than only oral communication, as

is the case in the Celce-Murcia et al. model, and was generally used in the broader fields of applied linguistics, second-language acquisition, and language testing, rather than only by ESL

curriculum developers and practitioners (see table 3, p. 20, in Bournot-Trites et al. 2015 for a comparison of Bachman and Palmer 1996 and 2010 and Celce-Murcia et al. 1995). However, the

Celce-Murcia et al. model was retained in an appendix, because it was an adaptation of the Bachman and Palmer model, and because it provided helpful concrete and detailed strategies to language

teachers for use in the classroom.

In summary, Phase I answered a real-world problem as a result of a national consultation, then it made sure that the common theoretical framework reflected the two original frameworks while

being grounded in the best and most up-to-date language development and assessment theories, as well as in language-teaching research.

Phase II: Content validity of the scales and concurrent validity of the common theoretical framework

As indicated above in the list of steps recommended in design-based research for projects (Jacobsen 2014, Reeves, Herrington, and Oliver 2005), Phase II was concerned with the construction and

design of the implementation: the CLB and NCLC scales. In this case, a working version of the CLB and NCLC had already been created and used; therefore, the first part of this second phase had

to do with verifying whether the CLB and NCLC corresponded to the common theoretical framework and revising them or the common theoretical framework if needed. Another part of the second phase

was involved in establishing congruence between the CLB and NCLC common theoretical framework and other widely accepted frameworks.

Accordingly, the next step was to compare the descriptors contained in the CLB and NCLC scales and the new common theoretical framework. To do this, six independent experts were selected

according to the same criteria as in the previous phase. However, to make sure there was consistency in the process, some experts had to work on both the CLB and the NCLC. Therefore, the six

experts were selected from both ESL and FSL fields, with four of them being bilingual. This group of experts was made up of researchers and practitioners working together: researchers,

curriculum designers, and language co-ordinators.

To carry out this correspondence-analysis task, the experts were provided with an Excel file for each skill – listening, reading, writing, speaking – in which each line of the first

two columns was a component or subcomponent of communicative competence as described in the draft common theoretical framework according to Bachman and Palmer (2010) and Celce-Murcia et al.

(1995), as well as La Nouvelle Grammaire (Chartrand et al. 1999, Pinsonneault and Boivin 2008, Riegel, Pellat, and Rioul 2009), a pedagogical approach to teaching grammar that was

included in the NCLC framework. These first two columns were followed by twelve columns corresponding to the twelve benchmarks of each scale. The task of the experts was to match each

descriptor with a corresponding component or subcomponent. In the case of a descriptor for which no corresponding component or subcomponent could be found, the descriptor had to be highlighted

in the CLB or NCLC working document. Two experts were working on each stage (beginner, intermediate, and advanced scales), but they were asked to work individually at first and then together.

They were each assigned a block of four benchmarks for each skill for the CLB and six benchmarks for each skill for the NCLC. In summary, their work was to find which elements of the

theoretical framework were found in each benchmark and which descriptors did not correspond to any element of the theoretical framework. After their individual work, they attended a four-day

meeting (two days for descriptors in English and two days for descriptors in French) where they compared their results with their partners and reached a consensus wherever there was

disagreement. First, the two experts who had worked on the same descriptor levels compared their results to verify if they had the same results, then the entire panel discussed any point of

disagreement. In addition, the panel discussed the broader congruence between the theoretical framework and the CLB and NCLC.

As a result of this analysis, several recommendations for revision to the descriptors were made. A detailed list of the recommendations can be found in the validation reports (Bournot-Trites

and Barbour 2012, Elson 2012a, 2012b). Mainly it was suggested that, during the revision of the scales and before field testing, gaps found during the validation process be filled where it was

developmentally appropriate. For example, some language functions might not be appropriate for beginners and therefore should not be included in the lowest benchmarks levels.

In general, it was noted that the CLB were congruent with the common theoretical framework; however, it was suggested that more elements of grammatical knowledge be included (including

vocabulary, syntax, and morphology/graphology), as well as elements of the strategic competence in individual CLB levels when these elements had a clear logical link with the descriptors at a

particular level. The panel also found that pronunciation and grammar elements were stated according to a deficit model – in terms of how they hampered communication – and it was

recommended that they be stated in a positive manner, as what the learner could do, instead.

On the other hand, the NCLC were generally found to be not congruent with the theories on which they were supposedly based. All the elements of the common theoretical framework

could be found in the NCLC descriptors, but their sequencing was not always logical. The validation report (Bournot-Trites and Barbour 2012, 12) stated: “The panel recommended a

significant revision of the indicators used to show progression by, a), providing more information about performance within the indicators and, b), revising the presentation and progression of

indicators and ‘Profil de l’apprenant’ in a way which would allow users to better track the progression of language ability through the levels.”

Furthermore, no elements of La Nouvelle Grammaire (Chartrand et al. 1999) were found in the descriptors of the NCLC; therefore, this theoretical aspect was taken out of the common

theoretical framework and only retained in an appendix related to pedagogy.

The panel also provided feedback on the assessment and pedagogy sections of the common theoretical framework. Their recommendations were mainly editorial in nature. One major recommendation was

to include self-assessment and peer assessment as ways to evaluate strategic competence and cognitive strategies that are difficult to observe directly from the production of the learners.

After the examination of the congruence between the common theoretical framework and the CLB and the NCLC, and once the recommendations for revisions in all the documents were submitted, the

CTF was examined in terms of concurrent validity with the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) (Council of Europe 2001), the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Language

Proficiency Guidelines (ACTFL Guidelines) (American Council for the Teaching of Foreign Language 1982, American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages 1999), and

L’Échelle québécoise des niveaux de compétences en langue seconde pour les immigrants adultes (EQ) (Gouvernement du Québec 2011). The CEFR and the ACTFL

Guidelines were chosen because they are well recognized and have a long history of development, and the EQ was chosen because it was a Quebecois reference.

For this theoretical concurrent validity process, a standardized questionnaire, including twenty-four questions, was sent to four experts who had in-depth knowledge of the common theoretical

framework as well as the other frameworks. The questionnaire was sent in French to the experts analysing the Échelle Québécoise. Thus, the revised common theoretical

framework was validated against each of the three other frameworks by two independent academics with expertise in their respective frameworks. The main themes guiding the questions were:

theoretical model, number of skills, concept of a benchmark, task as a basic element, functional approach, knowledge types (textual, grammatical, cultural, sociolinguistic), strategic

competence, pedagogy, and assessment.

From this analysis, the CEFR was found to have many similarities with the Common Theoretical Framework. There were some differences in categorization of elements between the two frameworks. In

addition, the CEFR showed its greater maturity through more expansion of basic elements and in assessment development. One major difference between the two frameworks was the number of skills.

The CLB and NCLC have four skills (writing, reading, listening, and speaking), whereas the CEFR has four modes (reception, interaction, production, and mediation), each split into spoken and

written, which results in eight skills. The validity report states: “From this analysis by our experts, it became clear that the Common Theoretical Framework and the CEFR had many

similarities. There are no fundamental differences between them. Where there are differences, they are mainly expansions of basic elements in the CEFR, probably due to the maturity of, and the

multi-national resources behind, the framework” (Bournot-Trites and Barbour 2012, 18).

In contrast, the new CTF was found to have a low concurrent validity with the ACTFL Guidelines for two reasons: because of a discrepancy between the goals of the two frameworks, and because the

ACTFL Guidelines are not based on a theoretical framework but on the examiners’ experience. Indeed, their construct validity has been criticized by researchers in the field of language

testing (Bachman and Savignon 1986, Fulcher 1996, Liskin-Gasparro 2003). Liskin-Gasparro (2003) wrote in her review of the ACTFL Guidelines, and particularly the Oral Proficiency Interview

(OPI):

A review of the research and critiques on the ACTFL Guidelines and the OPI (see Freed, 1988; Liskin-Gasparro, 2000) leads to the conclusion that proficiency as described in the ACTFL

Guidelines is far less absolute and broad based than the early proponents had claimed. Its empirical basis is shaky, and its claim to be conversational does not hold up. It is clear that oral

proficiency ratings predict far less about an individual’s future performance in a range of communicative situations than promoters of the OPI would like them to. (488)

As for the EQ, it was difficult to compare it to the new common theoretical framework because it was not a theoretical framework as such but, as its name indicates, only a scale. However,

although the EQ terminology is adapted to the Quebecois context, it is inspired by the NCLC as well as the CEFR (Gouvernement du Québec 2011) and is based on a communicative approach. The

summary of the validation report (Bournot-Trites and Barbour 2012, 23) indicates that “the independent experts did not identify any direct contradiction between the EQ and the CTF.”

In summary, this second phase established the theoretical content and concurrent validity of the CLB and NCLC. This was done by linking theory and practice, as well as researchers and

practitioners, as shown in the description of Phase II of the validation study. As a result, revisions were made to the CLB and the NCLC and to the common theoretical framework. This phase was

followed by a study of the content validity of the descriptors in a repeated cycle of revisions, trials, and reflection.

Phase III of the validation process: Field validation

Phase III, determining the validity and reliability of the revised CLB and NCLC scales, was a very important step of the process, where practitioners were brought back into the project again.

After establishing a common theoretical framework based on the most recognized theories related to language teaching and assessment, and verifying the congruence of the common theoretical

framework with the CLB and NCLC descriptors and other recognized language frameworks, the goal of Phase III was to “establish whether practitioners who have experience with and

understanding of the benchmarks, see the revised CLB and NCLC as valid and accurate descriptors of authentic language performance” (Elson 2012b, 1, 2012a, 1). This third phase aimed also

at establishing reliability of the CLB and NCLC, that is, finding out if various people would interpret the revised benchmarks in the same way. For the purpose of this chapter, since the same

method was used for both CLB and NCLC, only the process with CLB is reported here.

At the beginning of Phase III, a team of content developers created authentic tasks and scenarios – 89 listening tasks, 25 speaking tasks, 109 reading tasks, and 24 writing tasks –

reflecting benchmarks for each skill. It is important to note that the produced exemplars were authentic and that the scenarios corresponded to several benchmarks, rather than to one particular

benchmark.

Then the field validation was done in two steps by two groups. First, a group of experts reviewed the descriptors and exemplars for each skill at each level, and second, a larger group of

practitioners worked on the validation and reliability per se of the CLB. This method ensured that the perspective of experts, as well as that of the practitioners, was taken into

account and that they were in agreement.

In the first step, a panel of six experts was selected after a call for expression of interest was distributed as widely as possible. The selection criteria were very precise and included

knowledge of the CLB, experience in teaching applied linguistics or second-language pedagogy, training in ESL teaching, and scholarly activity (including conference presentations and

publications), as well as geographic representation. This ensured that experts really were experts in the appropriate areas.

Once the experts were chosen, the validation task was sent to them, along with the exemplars. Their responsibility was to assign “what they saw as the lowest appropriate CLB level

necessary, to effectively carry out those tasks or to describe the language samples provided” (Elson 2012a, 2). A high correlation between the experts would indicate a high reliability.

“A high degree of correlation among raters in the benchmark levels assigned to the exemplars and tasks also validates the benchmark descriptors for each task” (6). Besides

attributing a benchmark to each exemplar, the experts were given a second task. They had to judge the authenticity and representativeness of each descriptor compared to language use, via a

four-point Likert scale: 1-Not Representative; 2-Representative with substantial revision; 3-Representative with minor revisions; 4-Representative. This second task would help to establish the

validity of the descriptors.

Based on the six responses of the experts, the validation project lead determined the final benchmark level for each exemplar. Calculated inter-rater reliability coefficients ranged from .83 to

.89, indicating strong reliability. Validity of the descriptors was equally high, as shown by the content validity index (CVI), “No combined CVI ratings for 3 and 4 fell below 0.83. This

result supports confidence in the content validity of the revised CLB” (Elson 2012a, 12).

Importantly, the form given to the experts allowed for additional commentary by the raters. One key comment received was about the difficulty of distinguishing some benchmark levels from

adjacent ones. As a result, those benchmarks were revised to add more differentiation points between successive descriptors. Another type of comment suggested changing the level of some

descriptors, especially in stage 2. This important feedback afforded more refinement of the benchmarks and increased their validity. The author of the report (Elson 2012a, 12) indicated:

“Taken overall, the calculations of Interrater Reliability (IRR), the Content Validity Index (CVI), and the expert rater comments all support the conclusion that the revised CLB have

strong content validity and a high level of reliability. Six experts, acting independently, have been able to essentially agree on the accuracy of the revised benchmark descriptors.”

Following the experts’ validation work, field practitioners were called on for a “validity and reliability exercise” to further establish “the degree to which the

content of the revised benchmarks is authentic, relevant and representative of the larger language framework and the constructs from which they are sampled” (Elson 2012a, 12).

Practitioners have real-world experience and knowledge of the benchmarks from a user point of view, which is very important in assessing the validity and reliability of a measuring instrument

such as the CLB or the NCLC.

Out of 110 practitioners contacted, sixty-one contributed to the validity and reliability tasks. They represented all benchmarks levels, but more often the lowest stages of the benchmarks, and

all regions of Canada, but especially Ontario and British Columbia, where there are more ESL programs. Criteria for selecting practitioners included extensive experience teaching a second

language to adults in Canada, access to a classroom, and extensive familiarity with the benchmarks.

The practitioners were provided with a response form for each of the four skills, and a chart including all the scenarios and exemplars/tasks reviewed by the expert with the benchmark level

assigned to each after the work of the panel of experts, as well as the recordings, videos, and print materials related to the tasks. Practitioners had to indicate, using a four-point Likert

scale, if each of the descriptors was authentic and representative of the target language use – 4 being the most representative and 1 the least. Then they had to indicate if the level

agreed upon by the expert panel for each task was just right, too high, or too low, and provide an alternative level if applicable. Finally, practitioners were invited to give comments on the

two parts, of their task, validity and reliability.

The results indicated that 80 percent or more of the responses about the authenticity and representativeness of the descriptors were within the 3 and 4 ratings, except for benchmark 6 (across

all four skills). In summary, the report declared that, “these figures indicate that across a wide range of practitioners, the results for Part 1 show strong support for the content

validity of the revised benchmarks” (Elson 2012a, 18). These ratings, coupled with the comments, provided opportunities to make the descriptors even more efficient and valid.

The second part of the exercise provided more evidence of the validity of the levels assigned to the tasks and the reliability of the benchmarks themselves, “since a high level of

agreement on ratings for particular tasks indicates that the benchmarks are clear and accurate in their description, and can be used and applied repeatedly in a reliable and consistent way

across programs and field practitioners” (Elson 2012a, 19). Results showed a high percentage of practitioners indicating that the benchmark level assigned to each task was just right: 79

percent for the listening tasks, 76 percent for the speaking tasks, 80 percent for the reading tasks, and 82 percent for the writing tasks, respectively. When three alternative ratings were

given for a task, it was recommended that the task be examined to see if an alternative benchmark designation was appropriate. Furthermore, all comments, such as those explaining why an

alternative benchmark designation was suggested, or other comments given by practitioners, were analysed and consideration was given to making more changes to the benchmarks or to improving

training of the practitioners. Many of the comments were positive, emphasising the improvement made to the benchmarks. In summary, the report (Elson 2012a, 25) states that, “In Part 2,

the field practitioners indicated overall agreement with the benchmark levels assigned by the experts to the tasks and exemplars in each skill category. This tells us that for most of the

respondents, the tasks are seen as valid in that they accurately reflect the benchmark levels assigned to them.”

In this Phase III of the validation, one can clearly see an iterative work of validation calling upon expert theoreticians as well as practitioners to establish the degree of validity and

reliability of the scales. Furthermore, the detailed reports of Phases I, II, and III give the context and various methods with which this validation has been established, and describe the care

with which the scales were adjusted and refined, taking into account a wide array of users and researchers. Undeniably, this illustration of design-based research at work is very different from

the traditional experimental method that was found inadequate by Brown (1992). It stems from real-world problems, it is as much grounded in theory as it is in the experience of practitioners,

it creates bridges between the two groups and takes into account their different perspectives to produce more adequate and valid results, and it engages practitioners in new endeavours and

ensures that the findings of research will be applied in the field. In sum, it is more suitable for educational research than more traditional research methodologies.

4. Conclusion

Design-based research is a relatively new methodology that shows great potential in being more appropriate in education than traditional research methods. The field of language teaching and

assessment is strongly rooted in theories of language and language acquisition. However, language is used in the real world and usage evolves. Therefore, research in language assessment can

neither be cut from theories nor from practice. Research questions and problems related to language assessment can be born from practice as much as from theories. The example of the revision of

the CLB and the NCLC theoretical framework and scales has shown that it was problem-driven and that practitioners initiated the revisions by expressing a need to improve the existing scales. In

turn, researchers used theories to guide the reformulation of the theoretical framework and collaborated with experts and practitioners to validate the revised documents and fine-tune them.

They used a variety of methods, including a survey, questionnaires, open-ended questions, expert reviews, statistical analyses, and consensus building, to arrive at a product that is more

satisfactory for all its users. In this way, researchers generated a new theoretical framework and two scales, the CLB and the NCLC, which were tried out in authentic contexts. Practitioners in

collaboration with experts were able to demonstrate consequential validity (Messick 1989) through their analysis and feedback. Such a design-based research methodology created a bridge between

theory and practice and between researchers and practitioners, improving practice and theory in tandem.

Taken together, the different phases of the revision of the CLB and the NCLC and the validation studies demonstrate that the CLB and the NCLC have a strong content validity and reliability.

After the refinement of the benchmarks following those studies, researchers and practitioners can use them with confidence, knowing that they rest on a strong theoretical basis and are

empirically sound. This would not be possible if they had been developed only by researchers based on theories or only by practitioners based on experience.

The strength of the CLB and the NCLC comes from the design-based research methodology used to improve them. Two distinctive features of this method are crucial in any assessment endeavour:

consideration of a diversity of perspectives and involvement of a variety of stakeholders. First, the theoretical frameworks as well as the scales have been examined, analysed, and critiqued by

different stakeholders offering a variety of perspectives, knowledge, experience, and expertise. This approach improved the Common Theoretical Framework (CTF) and the scales, and in turn made

them more valid. As Brandon (1998) has shown, evaluators who use the expertise of all suitable stakeholders through careful methods of data collection ensure that they increase evaluation

validity. Second, in general, people value more highly the products they participate in creating. In this case, because stakeholders were involved in the co-creation and validation of the CTF

and the scales, they and the people they represent, such as researchers, curriculum developers, and language co-ordinators, will value them more. Involving a variety of stakeholders in this

process will bring change in language assessment in Canada by creating a higher level of engagement of users. Involvement through representatives increases ownership and therefore the feeling

of control, which in turn brings commitment. Because of this partnership, the likelihood of the scales being acceptable and therefore accepted by users in the field is amplified, and the CLB

and NCLC stand to become models for other language descriptors.

References

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. 1982. Provisional Proficiency Guidelines. New York: Hasting on Hudson.

_____. 1999. ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines for Speaking (Revised). Accessed May 30, 2016. http://www.actfl.org/files/public/Guidelinesspeak.pdf.

Anderson, Terry, and Julie Shattuck. 2012. “Design-Based Research: A Decade of Progress in Education Research?” Educational Researcher 41(1): 16–25.

Bachman, Lyle F. 1990. Fundamental Considerations in Language Testing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bachman, Lyle F., and Adrian Palmer. 1996. Language Testing in Practice: Designing and Developing Useful Language Tests. New York: Oxford University Press.

_____. 2010. Language Assessment Practice: Developing Language Assessments and Justifying Their Use in the Real World. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bachman, Lyle F., and Sandra J. Savignon. 1986. “The Evaluation of Communicative Language Proficiency: A Critique of the ACTFL Oral Interview.” Modern Language Journal

70(4): 380–390.

Barab, Sasha, and Kurt Squire. 2004. “Introduction: Design-Based Research: Putting a Stake in the Ground.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 13(1): 1–14.

Bournot-Trites, Monique, Ross Barbour, Monika Jezak, Gail Stewart, and Daphné Blouin Carbonneau. 2015. Theoretical Framework for the CLB and NCLC. Ottawa: Citizenship and

Immigration Canada.

Bournot-Trites, Monique, and Ross Barbour. 2012. Unpublished Report on Phases I and II of the Validation of the Canadian Language Benchmarks and Niveaux de Compétence Linguistique

Canadiens. Ottawa: Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks.

Brandon, Paul R. 1998. “Stakeholder participation for the purpose of helping ensure evaluation validity: Bridging the gap between collaborative and non-collaborative evaluations.”

American Journal of Evaluation 19(3): 325-337.

Brown, Ann L. 1992. “Design Experiments: Theoretical and Methodological Challenges in Creating Complex Interventions in Classroom Settings.” The Journal of the Learning

Sciences 2(2): 141–178.

Celce-Murcia, Marianne, Zoltan Dörnyei, and Sarah Thurrell. 1995. “Communicative Competence: A Pedagogically Motivated Model with Content Specifications.” Issues in Applied

Linguistics 6(2): 5–35.

Chartrand, Suzanne-G., Denis Aubin, Raymond Blain and Claude Simard. 1999. Grammaire Pédagogique du Français d’aujourd’hui. Boucherville: Graficor-La

Chenelière.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 1996. Canadian Language Benchmarks: English as a Second Language for Adults. English as a second language for literacy learners (working document).

Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada, and Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks. 2012a. Canadian Language Benchmarks: English as a Second Language for Adults. Ottawa: Citizenship and

Immigration Canada.

_____. 2012b. Niveaux de compétence linguistique canadiens : français langue seconde pour adultes. Ottawa: Citizenship and Immigration Canada.

Cobb, Paul, Jere Confrey, Andrea diSessa, Richard Lehrer, and Leona Schauble. 2003. “Design Experiments in Educational Research.” Educational Researcher 32(1): 9–13.

Collins, Allan. 1992. “Toward a Design Science of Education.” In New Directions in Educational Technology, edited by Eileen Scanlon, and Tim O’Shea, 15–22.

Berlin: Springer Verlag.

Collins, Allan, Diana Joseph, and Katerine Bielaczyc. 2004. “Design Research: Theoretical and Methodological Issues.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 13(1):

15–42.

Conseil de l’Europe. 2001. Cadre Européen Commun de Référence pour les Langues: Apprendre, Enseigner, Évaluer. Paris: Didier.

Dede, Chris. 2004. “If Design-Based Research Is the Answer, What Is the Question? A Commentary on Collins, Joseph, and Bielaczyc; Disessa and Cobb; and Fishman, Marx, Blumenthal, Krajcik,

and Soloway in the Jls Special Issue on Design-Based Research.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 13(1): 105–114. doi: 10.1207/s15327809jls1301_5.

Elson, Nicholas. 2012a. Unpublished Final Report on the Benchmarking of the Revised Canadian Language Benchmarks (CLB) by the Expert Panel and Field Practitioners. Ottawa: Centre for Canadian

Language Benchmarks.

_____. 2012b. Unpublished Final Report on the Benchmarking of the Revised Niveaux De Compétences Linguistique Canadiens (NCLC) by the Expert Panel and Field Practitioners. Ottawa: Centre

for Canadian Language Benchmarks.

Fulcher, Glenn. 1996. “Invalidating Validity Claims for the ACTFL Oral Rating Scale.” System 24(2): 163–172.

Germain, Claude, ed. 1991. Le Point sur l’approche communicative en didactique des langues. Montreal: CEC.

Government of Quebec. 2011. L’échelle Québecoise des Niveaux de Compétence en Français pour les Personnes Immigrantes Adultes. Montréal: MICC-MELS.

Halliday, Michael, and Alexander Kirkwood. 1974. La Base Fonctionnelle du Langage. Langages 34:53–73.

Jacobsen, Michele. 2014. “Design-Based Research.” Education Canada 54(5): 22–24.

Liskin-Gasparro, Judith E. 2003. “The ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines and the Oral Proficiency Interview: A Brief History and Analysis of Their Survival.” Foreign Language

Annals 36(4): 483–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2003.tb02137.x.

Littlewood, William. 1981. Communicative Language Teaching: An Introduction. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Messick, Samuel. 1989. “Validity.” In Educational Measurement. 3rd edition. Edited by Robert L. Linn, 13–103. London: Collier Macmillan Publishers.

O’Donnell, Angela M. 2004. “A Commentary on Design Research.” Educational Psychologist 39(4): 255–260. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep3904_7.

Pawlikowska-Smith, Grazyna. 2000. Canadian Language Benchmarks 2000: English as a Second Langauge for Adults. Ottawa: Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks.

_____. 2002. Canadian Language Benchmarks 2000: Theoretical Framework. Ottawa: Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks.

Pinsonneault, Reine, and Marie-Claude Boivin. 2008. La Grammaire Moderne: Description et Éléments pour sa Didactique. Montreal: Beauchemin/Chenelière Éducation.

Reeves, Thomas C., Jan Herrington and Ron Oliver. 2005. “Design Research: A Socially Responsible Approach to Instructional Technology Research in Higher Education.” Journal of

Computing in Higher Education 16(2): 96–115.

Riegel, Martin, Jean-Christophe Pellat, and René Rioul 2009. Grammaire Méthodique du Français. Paris: PUF.

Sarrazin, George. 2010. Niveaux de Compétence Linguistiques Canadiens: Français Langue Seconde Pour Adultes (Document De Travail). Ottawa: Centre des niveaux de

compétence linguistique canadiens.

Wang, Feng, and Michael J. Hannafin. 2005. “Design-Based Research and Technology-Enhanced Learning Environments.” Educational Technology Research and Development 53(4):

5–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02504682.

Note

1 Messick originated the expression “consequential evidence or validity.”