Chapter 5

Mobilization, 1907-1910

I am a black dot, one out of the anonymous mass of my race, who longs for the claim of my people through our own effort, through the compact union and solidarity of our family.

— Letter to Previsión

From the beginning of the U.S. occupation of 1906-9, Afro-Cubans from various regions publicly criticized the new order. Ignoring white politicians’ command that they silence their demands in order to speed up the departure of the North Americans, they protested their continuing marginalization and demanded equality in all aspects of their lives. Their mobilization culminated in 1908 with the successful creation of a black party that, after the occupation, challenged Cuba’s political, social, and ideological structures.

Increasingly, Afro-Cubans claimed that their massive participation in the independence struggle had proven their commitment to the republic, which, in return, owed them sociopolitical recognition and a rightful share of public jobs.1 Two members of the short-lived Comité de Veteranos de Color, Evaristo Estenoz and Ricardo Batrell, played a leading role in post-August 1906 Afro-Cuban mobilization. Both veterans of the War for Independence and the August Revolution, they had high hopes for their future. The matancero Batrell was now in his late twenties and still lacked stable employment. Estenoz, the oriental son of a black mother and a white father, had a broader education and worldview than Batrell. Thirty-five years old, he lived in Havana, where he was a private contractor and also operated a French boutique with his wife. He had been in Europe and, in 1905, had traveled with Rafael Serra to the United States to visit with black organizations. A man of pride and ambition, he had participated in politics and protests since 1899. Together with other Liberals, he had been arrested in late 1905 for conspiracy against the Estrada Palma government; he was sentenced to longterm imprisonment but was pardoned six months later. During the August Revolution he was promoted to general.2

By late 1906, some black officers and soldiers of the Constitutional Army, including Estenoz and Batrell, were convinced that if the Liberal party acceded to power, blacks would continue to be disregarded for public promotion. They based their conviction on the proceedings of the Committee of Petitions, allegedly an all-white body that recommended white Liberals for jobs rather than veterans of the Constitutional Army. Estenoz personally made this claim to the U.S. military governor, Gen. Charles E. Magoon, in a meeting in December. As Estenoz visited black associations in the cities of Santa Clara and Cienfuegos, both strongholds of José Miguel Gomez, Afro-Cubans dissatisfied with the way the Liberal party treated them began to discuss the idea of creating a black party. Politics consisted of public jobs, they said at one meeting, and public jobs went only to whites. This was unjust, because blacks were as Cuban as whites and had made up the majority of the troops in Cuban revolutions. Obviously, they claimed, revolutions benefited only whites.3

By mid-1907, the idea of a black party had gained ground. From April to August, Afro-Cubans issued manifestos in several towns. Although they were all different in style and emphasis, most manifestos protested that Afro-Cubans had not received the consideration and the positions they deserved, although they had “shed rivers of blood for the fatherland.” They called on the raza de color to wake up and to unite across party membership in order to get their rights. They advocated the creation of a large independent black party, which would get black congressmen elected and would represent black interests. Anticipating white accusations of racism, they countered that for Afro-Cubans to organize politically was a constitutional right.4

The most elaborate declaration was the long “Manifesto to the People of Cuba and to the Raza de Color,” issued in July 1907 by Batrell and Alejandro Neninger, another Afro-Cuban veteran. Written in the form of a bill of indictment, it designated blame for the injustices committed against Cuban blacks—injustices that violated Article 11 of the constitution, according to which all Cubans were equal. The principal culprit was the white Cuban elite, who had used the pretext of the first U.S. occupation to marginalize Afro-Cubans in all spheres. “After the independence war,” the manifesto read, “our white brothers told us that they were not giving us our rightful participation in the country’s jobs, because the Americans were imposing themselves, and that we needed to wait until the latter had left.” So, as proof of patriotism, Afro-Cubans waited. After May 1902, they waited another “six months, in order to see if it was true that those responsible for not fulfilling justice toward those of color were Americans or Cubans. And they became convinced that those responsible for the discrimination . . . were the Cubans, not the Americans. The latter had already left; and the Cubans were doing nothing to change the situation of the people of color in the nation.”5

Batrell and Neninger particularly incriminated white Liberal veterans, who had rallied to the support of blacks on the basis of the Manifesto of Montecristi but then had betrayed them by not providing them with public jobs in Liberal municipalities and provinces and by passing laws to promote white immigration. Under the second U.S. occupation, white Liberals not only avoided recommending blacks for government positions but also “predispose[d] the Americans against [some] elements of color, saying that these are ‘extreme radicals.’” In addition, white Liberals, despite a display of political differences with Conservatives (formerly Moderates), consorted with them in the select all-white associations Club Ateneo and Union Club.

However, the manifesto did not exonerate Afro-Cubans from responsibility in the social status quo. Calling on the memory of Antonio Maceo and the thousands of blacks and whites who died with him in the hope of bringing democracy and brotherhood to independent Cuba, it accused Afro-Cubans of collusion in the disgrace of the raza de color. Because of their silence, Afro-Cubans did “not deserve the moniker of a patriotic race anymore, but, on the contrary, that of a race unable to occupy the true position that History recognizes as [theirs] at the cost of many acts of heroism.” More precisely, Batrell and Neninger pointed their fingers at the most prominent black leaders. Guided by their personal interests, the latter were so closely associated with white politicians that “they have to become [their] accomplices, often unconsciously and sometimes consciously, because they are an insignificant minority at the top.” The manifesto concluded that only by organizing separately from whites would Afro-Cubans erase the “old tutelages” and be respected.6

Sanctioning the leverage in Cuban politics that the Platt Amendment gave to the U.S. government, Batrell simultaneously wrote to the U.S. secretary of war to “supplicate” him to solve all injustices perpetrated by the “Cuban people” against the “black race.” Repeating some arguments contained in his manifesto, he indicted white Cubans for fostering injustice against Cuban blacks; he said they aggravated their offense by “lowering the honor of the Cultivated Nation” of the United States, because they claimed that they acted with the approval of the North Americans.7 With this letter, Batrell naively hoped to incite the United States to back Afro-Cuban demands.

At the same time that some Afro-Cubans voiced their discontent, they formed associations and committees to defend their rights in various provincial towns. The movement seemingly gained momentum in July 1907 on the news that no more Afro-Cubans had been appointed as takers for the U.S-sponsored census of 1907 than for the census of 1899. The movement’s focus was the distribution of a proportional part of public offices to blacks as well as the creation of a black party. Militants reportedly had ceased to entrust the Afro-Cuban cause to Juan Gualberto Gómez and Martin Morúse to Juan Gualberto Gómez and Martina Delgado, because both of these men had “separated themselves from the negro race by failing to push their claims with sufficient force.”8 Although sociedades de color asked him to represent their interests in Havana, Gómez “did not look after anybody and did not answer to anybody.”9 In early August, several Afro-Cubans held a meeting at the sociedad El Porvenir in San Juan y Martínez (Pinar del Rio) and demanded one-third of the positions in public administration, in the rural guard, and in the police, including appointments as officers.10 In the province of Santa Clara, blacks gathered to discuss ways to get blacks elected as city council members, mayors, and legislators in order to ensure employment for Afro-Cubans. In Placetas, in particular, about a hundred blacks had reportedly separated from the Liberal party to form a group of independents.11 In Matanzas, black leaders courted union workers and encouraged them to resort to strikes, “because strikes were just and would unify and elevate the colored race and make it easier for blacks to obtain equality and their just rights.” 12

Among the movement leaders identified by U.S. information officers were, in the province of Pinar del Río, Lucas Marrero and the jail-keeper Gen. Ramón Pozo; in the province of Santa Clara, Gen. Eloy González in Cienfuegos, Neninger in Colón, and Batrell in Santa Clara; in Santiago de Cuba, General Hierrezuelo and Bernardo Camacho; in Matanzas, the bricklayer and labor leader Claudio Pinto.13 Evaristo Estenoz was undeniably coordinating the movement. During the summer of 1907, he traveled extensively in Pinar del Rio and Santa Clara, where he participated in meetings of blacks. He also wrote to several Afro-Cuban veteran officers, calling on them to organize blacks in order to force recognition of their rights. In late August he declared that he was disgusted with the government and was organizing blacks all over the island; he threatened to prepare them for war if the North Americans did not organize elections soon.14

Yet such mobilization was not unanimously approved by Afro-Cubans. In August, the Directorio de la Raza de Color de Camagüey, headed by Emilio Céspedes, issued a manifesto rejecting the idea of a black party. Afro-Cubans should be able to militate in the party of their choice, the petition said, although they needed an organization to help them get an education, a proper percentage of public jobs, and the recognition of their race. Indeed, the Camagüey Directorio expressed a strong racial pride and consciousness. Its members felt “happy with this color that Nature gave to [them].” They thanked “the Creation for having made [them] physically strong for labor and morally big so that [they] love the whole world.” And they lamented the fact that as soon as blacks organized to take care of their problems, they were accused of racism and antinationalism.15 Still another group of Afro-Cubans from Camagüey opposed even the idea of a nonpolitical black organization. Instead, they recommended the establishment of black businesses and the increase of black training and education.16

Most veterans contacted by Estenoz, notably Gens. Silverio Sánchez Figueras and Jesus Rabí, refused to back his initiative. Some feared that the creation of a black party would harm the Cuban commonweal and stimulate white racism; others were concerned about the U.S. reaction.17 Comdr. Tomás Aguilar argued that “to make collective appearances as a race” when Cuba was under the military occupation of a nation in which “our race . . . is subject to the most irritating despotism” could threaten the future of Cuban independence. According to Aguilar, Afro-Cubans should have patience and draw more closely around José Miguel Gómez, who had promised to favor them if he became president.18 As for Batrell, he backtracked and used the threat represented by Estenoz to try to advance in Alfredo Zayas’s faction of the Liberal party under the patronage of Juan Gualberto Gómez.19

In reality, hopes of upward mobility through allegiance to mainstream parties had not disappeared altogether, even among the protesters. Estenoz himself had not broken all ties with José Miguel Gómez.20 Morú continued to draw Afro-Cubans supporters to the miguelista wing of the Liberal party, while Juan Gualberto Gómez still had sufficient influence to convince some blacks tempted to follow Estenoz to remain with him in the zayista faction.21 Since his election as representative for the Liberal party in 1904, Generoso Campos Marquetti had ceased to speak up for black rights.22 At a meeting at the Havana sociedad Arpa de Oro in September 1907, two hundred Afro-Cubans discussed the creation of a black organization proposed by the manifesto of Camagüey. Zayistas Juan Gualberto Gómez and Campos Marquetti opposed the project on the basis that equality was guaranteed by the constitution. The Conservatives Rafael Serra and Lino D’Ou, along with Miguel A. Céspedes and Juan Bravo, voted in favor of the creation of a new Directorio Central and elected its leadership.23 Apparently, however, the black organization did not materialize.

Not discouraged by these setbacks, Estenoz continued to mobilize Afro-Cubans. By May 1908, he issued a circular cosigned by about one hundred men, in which they claimed to have two thousand followers and announced that they would not tolerate further discrimination, insult, or delay to reforms. In mid-May, Estenoz was arrested because of a dispute with a messenger boy. Rather than weaken his movement, this incident galvanized his supporters, who saw it as a political maneuver. They organized committees and meetings on Estenoz’s behalf to force white politicians to endorse his candidacy as a senator. After his acquittal, Estenoz resumed his efforts.24

The provincial and municipal elections of 1 August 1908 proved disastrous for the black candidates running in the mainstream parties; so finally, on 7 August, Estenoz, the black journalist Gregorio Surín, and a group of followers founded the Agrupación Independiente de Color in Havana, whose name was later changed to the Partido Independiente de Color. At the end of the month, they began to publish the newspaper Previsión, the movement’s organ. Their immediate goal was to win seats in the congressional elections of November 1908. Though they met every night at Estenoz’s home to select candidates, the Agrupación members managed to present electoral lists only for the provinces of Havana and Santa Clara. Just a few weeks after the party was created, its first political attempt ended in failure.25 The reunited zayista and miguelista Liberals won a sweeping victory; José Miguel Gómez was elected president of the republic, and Alfredo Zayas vice president.

Despite its name, the Partido Independiente de Color advocated not black separatism but Afro-Cubans’ integration into society and participation in government “in order to be well governed.” Its political program addressed only a few issues directly related to race: it demanded an end to racial discrimination, equal access for Afro-Cubans to positions in public service and the diplomatic corps, and an end to the ban on “nonwhite” immigration. Most of the other demands aimed at improving the conditions of the popular classes regardless of race: expansion of compulsory free education from eight to fourteen years; provision of free technical, secondary, and university education; state control of private schools; abolition of the death penalty; reform of the judicial and penitentiary systems; establishment of the eight-hour work day and of a system that gave Cubans priority in employment; and the distribution of national lands to Cubans.26 As Previsión summarized, “Our motto for the time being is ‘Cuba for the Cubans,’ our profession of faith, state liberalism.”27

Indeed, most independiente demands were shared by other political parties. Only the claim for public jobs for blacks and opposition to the ban on “nonwhite” immigration were exclusive to the Partido Independiente de Color. All other parties, including the Partido Obrero Socialista, continued to ignore the issue of black employment and supported European immigration in families rather than on an individual basis. As for Previsión, it followed the path of El Nuevo Criollo in declaring that the government’s goal behind the often-subsidized European immigration was “to whiten the horizons” and “to destroy [the Afro-Cubans], even though in the slow way” of demographic change. It ironically asked, “If black Americans were coming to Cuba, would the government refuse them entrance?” It requested true democracy in immigration policy, “except for those [immigrants] who would be inadmissible because of their considerable lack of education.”28 Such a proposition was not without problems, because “nonwhite” immigrants would have competed with Afro-Cubans for lower-paying jobs.

Regarding Cuban-U.S. relations, the Partido Independiente de Color’s program opposed the Platt Amendment and demanded the revision of all legislation introduced during U.S. occupations.29 One contributor to Previsión claimed that if Cuba was to be reoccupied or annexed by the United States, Afro-Cubans would create a new homeland for themselves elsewhere in the world rather than face continuing marginalization.30 Simultaneously, however, the party’s leaders did not hesitate to use the Platt Amendment to force other parties to recognize their new movement. By doing so, they only replicated a tactic widely used by Cuban politicians of all tendencies.31 Previsión reproduced the letters exchanged between Magoon and Estenoz in the fall of 1908 to prove the party’s right to existence.32 On several subsequent occasions, it appealed for U.S. arbitration and resorted to the threat of provoking another U.S. intervention in Cuba if racial discrimination continued.

Independiente views about the United States and the condition of U.S. blacks were equally ambiguous. On one hand, Previsión portrayed the United States as the embodiment of venal attitudes and moral degeneration, where animals were better protected than human beings.33 The paper reproduced statistics and descriptions of blacks being lynched by “red-haired, ferocious, and vociferous crowds like hungry packs of hounds” in the South.34 On the other hand, Previsión theorized that unlike Cuba’s hidden variety of racism, U.S. racism, which was characterized by frank and absolute contempt for blacks, had the advantage of allowing African Americans to “form a powerful black family that does not need anyone to be happy.”35 Indeed, U.S. black businessmen, lawyers, medical doctors, and journalists impressed the independiente leaders, who established contacts with some of them.36

In general, however, the independientes did not advocate the isolation of blacks from Cuban society or the creation of a separate Afro-Cuban or African culture. On the contrary, as Estenoz told U.S. Special Representative Enoch H. Crowder when he asked the representative to recognize his party, the independientes wanted “to prove to the world the culture and civility of the Cuban race of color”37—and in the early 1900s, civility meant Western values and culture. Previsión stigmatized African dance and drumming as “barbarisms of bygone days” and manifestations of “African atavism.” Brujeria and traditional healing also had to be eradicated as reminders of a servile past. Previsión urged blacks to study and work hard. The newspaper campaigned for the legal marriage of Afro-Cuban couples, called for new legislation on illegitimacy, and insisted upon the immediate, free-of-charge, and legal recognition of children of couples who formalized their consensual unions through marriage. Previsión also exhorted the Catholic church to promote religious marriage among blacks through the ordination of Afro-Cuban priests.38

In other ways, the independientes remained traditional and within mainstream Cuban culture. The independientes’ campaign did not concede new rights to women. Whereas native and foreign white women entered some new professions faster than Afro-Cuban men, male leaders reasserted that the right place for a woman was at home serving her husband and raising her children. A series of articles entitled “El trato social” (social behavior) recommended, for example, that women should always side with their husbands, so that “male pride would not be hurt.”39 Previsión criticized the Catholic church for its Spanish orientation, its exclusion of Afro-Cubans from seminaries, and its racial discrimination in the observance of fast days.40 The newspaper was openly sympathetic to freemasonry. It recommended to its readers “the constant practice of these three simple virtues: abnegation, tolerance, and fraternity,” a message that had a strong Masonic connotation. Like several mainstream newspapers, Previsión announced the activities of lodges. Some independientes, including Estenoz, were masons, probably members of irregular lodges founded during the War for Independence. Others belonged to the Grand Unity Order of the Odd Fellows, an English-based fraternal secret society represented by three lodges of color in Cuba.41

Although at first sight the ideas espoused by the Partido Independiente de Color appeared broadly conventional, some of them definitively questioned the dominant ideology. Previsión refuted the theory of white supremacy, insisting that all human races belonged to a single species. Human unity was “the theological truth, the scientific truth.” Though skin varied in color, its composition was common to all races. In addition, human skull shape did not prove racial inequality, as one could find brachycephalic, dolichocephalic, and mesocephalic persons in every race.42 If all races are equal, an article concluded, “we do not long for black supremacy over whites; but neither do we accept, and never will, white supremacy over blacks.” Consequently, Previsión refused to make any distinctions within the race of color and to value mulattoes more than blacks for their partial European ascendancy: all belonged to the “Afro-Cuban family.”43 Such an understanding of equality, no doubt, did not fit the official concept of “equality based on merits.”

Furthermore, Previsión attacked the three main fears used to mobilize whites against blacks. First, the fear that Cuba would become another Haiti was groundless, as the independientes did not want to establish a black republic but only to improve the lot of Afro-Cubans. On the contrary, the newspaper claimed, in reality Cuba was becoming another United States, where blacks were discriminated against—an evolution that understandably provoked fears and resentment among them.44 Second, the scarecrow of the black brujo allegedly satisfying his cannibal instincts with innocent white infants was “a new [Conspiracy of La Escalera of 18]44,” a myth brandished by the white press to disqualify Afro-Cubans from public life. Previsión pointed out that even during Spanish rule, brujería had not been murderous. It denounced the alarmist campaign of mainstream newspapers, which daily reported false rumors: “‘The brujos have taken away two children in Havana, three in Matanzas, three in Cárdenas, and so on everywhere. Police intervened, the black man managed to escape, the child was saved miraculously,’ and other assertions that keep public consciousness stirred up and the poor blacks of this unfortunate land in terror.”45

Similarly, in their “crusade to discredit the black masses,” the Liberal and Conservative parties organized marches to the beat of African drums at election time.46 In fact, according to Previsión, both types of campaign aimed at portraying blacks as uncivilized Africans who were unfit for enfranchisement, in order to drag some antiblack legislation out of the U.S. provisional government. Also, belief in racial equality allowed independientes to challenge the taboo of black men’s having sex with white women. Seeking to overcome the icon of fear of the black rapist, they argued that intermarriage between Afro-Cuban men and white women should be considered as natural as intermarriage between white men and black or mulatto women.47

With regard to the development of the human race, Previsión also refuted the central role that the dominant elite attributed to Europe. The independiente paper took pride in locating human origin in Africa and in pointing out that Spain had been colonized by Africans during its Muslim age. It praised the power and beauty of the Queen of Sheba.48 Some elements in the party’s propaganda even indicate that its dismissal of African cultural heritage was not absolute. Although Previsión made no direct reference to santería, it occasionally mentioned the Supreme Being, the santería equivalent of Olorún-Olofí, the Yoruba deity of the Creation.49 Furthermore, the independiente leaders chose an unharnessed, hair-in-the-wind, rearing-up horse as the party’s symbol. They called on black Cubans to “vote for the Horse.”50 Yet the horse probably represented not only the epic of the independence wars but also Changó, the Yoruba spirit of fire, thunder, and lightning who corrects injustices and rights any wrong. Identified with Saint Barbara, a Catholic figure, Changó is conceived as a gigantic black man with an infectious smile and handsome, strong features. Patron of the warriors, Changó rides a white horse. In addition, the “horse” refers to the role of the medium (generally an initiate) that Changó “mounts” when he takes possession of him or her to communicate with the faithful. Though other Yoruba spirits also mount their mouthpiece, only Changó possesses his horse to the point that the latter loses consciousness and does dangerous things without being hurt.51 And last but not least, several Partido Independiente de Color members or sympathizers openly practiced African traditions. Lino D’Ou, who occasionally contributed to Previsión, was a ñáñigo member of the Abakuá secret society; Eugenio Lacoste, a paralytic independiente leader in Oriente, was a santería priest; and the veteran Julián V. Sierra did not hesitate to conclude one article in secret language:

Tamvuyé tiene razón:

Cuando túpilacusánda

Etáculamaculémnáaa!!52

In addition, some letters to Previsión showed a black nationalism and a racial pride much in the vein of the recent “Black Is Beautiful” movement in the United States. The mere fact that the editor chose to publish them demonstrates that they represented a current among the independientes and that he was not against its diffusion. One letter writer from Havana expressed his gratitude to Estenoz for having made, by publishing the newspaper, “one thing that is ours, ours, without mixing or blending with foreign bodies. I am a black dot, one out of the anonymous mass of my race, who longs for the claim of my people through our own effort, through the compact union and solidarity of our family.” And he added, “Whites’ god is made of marble. Why should our divinity not be made of ebony or iron? . . . Let us stand aloof from the alien, let us shut up in ourselves, let us make a circle, reconcentrate in it, and gather our race in its center. Let us make a stoic, strong, absorbing race; let us imitate the Jewish people, they are self-sufficient. . . . Black comes before everything.”53 Such self-esteem was shared by a young woman, whose subscription to the party’s newspaper accompanied these words: “I am very glad that this newspaper came into my hands, because I have always felt black, absolutely black. It seems that heaven put it in my hands to tell me: Here you have a Christ, General Estenoz, champion of your race, it is time that you show what you are as a black and Cuban woman.”54

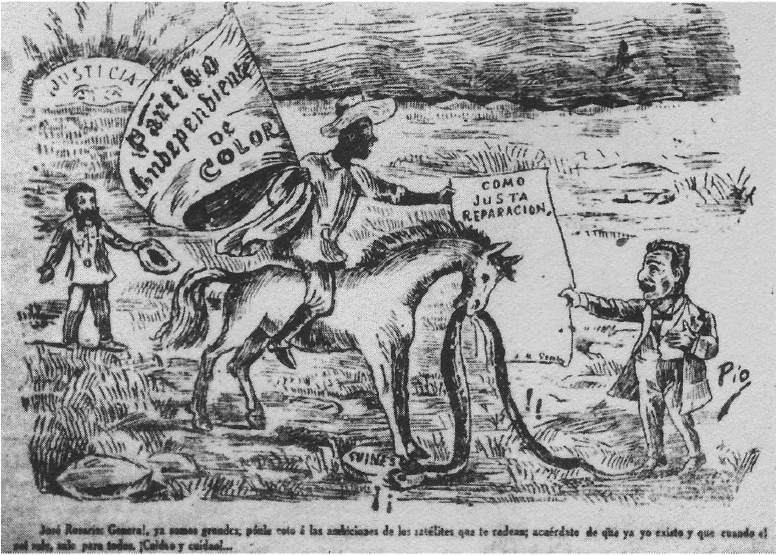

Pride in being black and Cuban, in sum, was the principal racial message of the independientes. They wanted Afro-Cubans to be recognized as a full component of Cuban nationality. Cuba was not only to be “for whites and for blacks,” as Martí had written; it was to be black and white as well. The party’s demand for jobs in the diplomatic corps was a symbol of the world visibility and representativeness they hoped to acquire as Afro-Cubans. To that effect, Sierra challenged in Previsión the cartoon representation of the typical Cuban as the white Liborio, and he created the character of the black José Rosario, similar to Changoós representation, to personify Cuban common sense and nationalism.

José Rosario, first names of his father and mother that he uses in remembrance of his parents. This Cuban is a man as black as a Cuban, young, of regular stature, of very sturdy constitution, with extremely white teeth that he only shows when he half laughs; of energetic character and of a worth close to foolhardiness, with little education but very good practical sense, of extremely simple habits and with no pretension whatsoever. He wears trousers and a striped shirt tucked into his trousers, closely cropped hair and completely shaved, shoes made of reed, a palm-leaf hat, always carrying a short machete in his belt, because he has earned all his belongings with this blunt instrument; and as he is a good horseman, he almost always uses leggings.55

Figure 5-1.

This Partido Independiente de Color cartoon from Previsión (30 March 1910) shows José Rosario on horseback demanding justice from President Gómez, with Liborio waiting for his share in the back. The caption has José Rosario declaring, “General! We are big, now; set limits to the ambitions of the satellites who revolve around you; remember that I exist now and that when the sun rises, it rises for all. Careful and careful!” (Biblioteca Nacional “José Marti”)

Sierra used the characters of José Rosario and Liborio to explain his view of the history of black and white relations in Cuba. It was the story of José Rosario’s sufferings in slavery, commitment and sacrifice in the wars for independence, and exclusion in the republic (fig. 5-1). It was also the story of Liborio’s cruelty during slavery, cowardice in the wars, and betrayal of his black compatriot after independence. According to Sierra, the two men had shared a pact of honor to fight together for Cuba’s freedom and to share benefits in the new republic. But the ambitious and avaricious Liborio had broken his word at the end of the war. Out of fear of José Rosario’s revenge, he abandoned him, turned to the United States for protection, and sought alliance with the former Spanish enemy.56

The theme of whites’ betrayal of blacks after independence was not limited to the story of José Rosario; it pervaded the rhetoric of the party. Afro-Cubans made up more than 80 percent of the Liberation Army, Previsión repeatedly claimed; in the war of 1895-98, 82,000 blacks had died for Cuba’s freedom, compared with only 26,000 whites, Estenoz stated. Thus, Afro-Cubans had proven their patriotism and leadership better than white Cubans. But the latter had deprived the former of the fruits of victory. Now Afro-Cuban commitment to independence demanded that, in Martí’s words, they “[pursue] the revolution until the disappearance of the smallest injustice.”57

To sum up, independiente leaders did not hesitate to refute the myth of racial equality in Cuba. Without directly questioning Martí’s interpretation of slavery and abolition, they denounced white Cubans’ mistreatment of slaves. Rather than emphasizing blacks’ and whites’ fraternity in the independence struggle, they stressed Afro-Cubans’ overrepresentation in the Liberation Army and on the list of those who died for Cuba Libre. They also showed how elite white Cubans’ fear of blacks after independence had prompted some of them to seek alliance with the United States and with Spanish residents. Conscious that by challenging the founding myth of the Cuban nation they exposed themselves to the accusation of antipatriotism and black racism, they carefully substantiated their claims with quotations on equality from Martí.

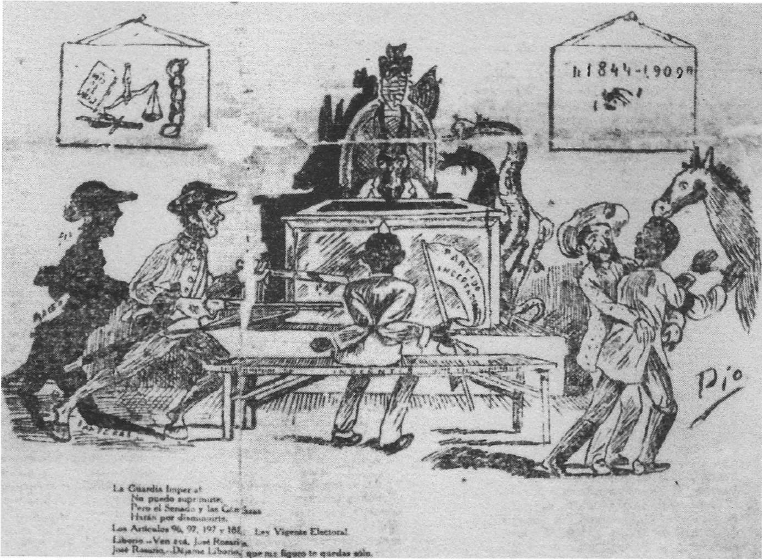

Nevertheless, in order to rally black supporters, they also built on Afro-Cuban collective memory of white repression and exploitation—two themes Martí had avoided. They repeatedly resorted to the symbolism of slavery and 1844 (the Year of the Lash) to show continuities in whites’ attitudes toward blacks. For example, one cartoon paraphrased Martí’s vision of equality and portrayed Afro-Cubans in the Liberal and Conservative parties as handcuffed cabbies, their feet confined in stocks, who were subjected to the whip of a white Cuban man (fig. 5-2).58

Another cartoon compared the repression of independientes in 1909 with the repression of blacks during the Conspiracy of La Escalera in 1844. The Partido Independiente de Color was symbolized by an innocent black man sitting on a bar, his arms tied behind his back. He faced Justice in the form of an ass dominated by the snake of racism. A gun was pointed at him by a black man wearing a white mask (probably Morú), who appeared from the shadow of the dead martyrs, Maceo and Banderas. The courtroom was decorated with two pictures, one of which showed the constitution turned upside-down, an unbalanced scale of justice, and the chain of slavery. Liborio attempted to seduce José Rosario, but the latter, in mourning, returned alone to the horse of the Partido Independiente de Color (fig. 5-3).59

Figure 5-2.

This cartoon from Previsión (10 December 1909) portrays blacks in mainstream political parties as castigated cabbies. The caption paraphrases Martí’s vision of equality: “Union . . . we are all equal. Long life to Democracy! Put up with a little more and you will save the fatherland. With all . . . and for all.” (Biblioteca Nacional “José Martí”)

By October 1909, the tone of the independiente organ turned virulent as it became obvious that José Miguel Gómez’s administration would not bring fundamental change to Afro-Cubans and reward participants in the August Revolution with public jobs.60 Liberals seemed more interested in highlighting the antiracist attitude evident in the appointment of Morúa as president of the Senate than in bringing about substantive reforms. Continued racial discrimination now became the major target of Previsión. Articles increasingly focused on cases of Afro-Cubans being turned down for jobs, denied service in restaurants and barbershops, and unfairly arrested or sentenced. Previsión labeled these incidents “moral lynchings” and included them on the long list of crimes against free blacks that started in 1844 with the Conspiracy of La Escalera.61 It argued that Cuban racism was particularly ugly because it was based on fear of blacks and was thus hidden. This characteristic of obscurity implied permanent white control of blacks, a system designed to prevent Afro-Cubans from thinking and acting on their own. Any sign of independent Afro-Cuban initiative terrified whites and servile blacks, who would always immediately respond, “Racism! Don’t divide the races!”62 The time for action had now arrived. Afro-Cubans were summoned anew, in the name of those who had fallen in the War for Independence, to oppose racism—even, if necessary, with violence. The fear of shedding blood or provoking another U.S. intervention and U.S. annexation should not deter them. They were even ready to abandon Cuba to save their honor.63

Figure 5-3.

This cartoon from Previsión (25 December 1909) denounces the biases of Cuban justice and legislation against the Partido Independiente de Color. The caption announces, “The Imperial Guard could not suppress you; but the Senate and the House will diminish you. Articles 96, 97, 197, and 181, Electoral Law in force.” Libório says, “Come here, José Rosario”; José Rosario replies, “Leave me, Libório, I imagine you stay alone.” (Biblioteca Nacional “José Marti”)

Simultaneously, Afro-Cuban affiliation in the Partido Independiente de Color was growing steadily. By early 1910 the party had developed into a sizable organization, with active members in most provinces and a national network of municipal committees. Previsión then claimed that the party had 60,000 members, including 15,000 veterans, 12 generals, and 30 colonels. These figures constituted 44 percent of Afro-Cuban voters, or 14 percent of all male citizens over twenty-one years of age, and were probably inflated.64 A more realistic estimate could be derived from Previsión’s approximate circulation of 9,000 in 1909, from the 15,000 shares issued by the party in 1910 in an effort to solve financial problems, and from the party’s structure on the island. In February 1910 the party had 146 registered municipal committees: by province, 53 in Santa Clara, 36 in Oriente, 32 in Havana, 13 in Pinar del Rio, and 12 in Matanzas. It was unable to gain a foothold in Camagüey, where Afro-Cubans represented only 18 percent of the population. But in the province of Havana, the independientes had established themselves in the capital, where they had their headquarters, and in the most important towns. In Oriente, the province with the highest percentage of Afro-Cubans—43 percent—they were well organized in the regions of El Cobre, Alto Songo, Santiago de Cuba, Guantánamo, and Baracoa. They encountered solid support in the province of Santa Clara, the stronghold of the miguelistas, where blacks and mulattoes represented no more than 28 percent of the population. In comparison, they were weak in Matanzas, whose population had the second highest percentage of Afro-Cubans (38 percent): they had no committees in such largely Afro-Cuban municipalities as Pedro Betancourt or Unión de Reyes.65 On the basis of these figures, it is likely that the party counted between 10,000 and 20,000 potential supporters.66 Nevertheless, these were impressive figures for an organization that had been in existence less than two years.

As their socioeconomic marginalization and lack of political opportunities continued unchecked, blacks and mulattoes increasingly became disenchanted and joined the independiente campaign in growing numbers. The campaign reached not only the literate, through Prevision and local protest manifestos, but also the illiterate, through political meetings attended by laborers and peasants and visits by propagandists to small villages and sugar centrales.67 The struggle against discrimination and the message of racial pride, more than the party’s political program, were the source of the independiente appeal. Most Afro-Cubans had at one time or another experienced such incidents as being refused a haircut by a white barber, denied a job, or suspected of an offense just because of their color. The perception of the campaign as a continuation of the independence struggle recalled times of hope, heroism, and companionship and thus diminished the sense of resignation.

The Partido Independiente de Color had a broad popular origin. With the exception of Lino D’Ou, a Conservative veteran and congressman from Oriente (who never joined the party but occasionally contributed to Previsión), it lacked the backing of any outstanding national leader with the ability to provide patronage. Only Estenoz occasionally made the front page of the national press. Most independiente leaders belonged to the middle class: Estenoz was a small contractor; Gregorio Surín, a journalist; and Pedro Ivonnet, an untrained rural-guard veterinarian and a Conservative who joined the party in February 1910 to become second in command. But Julián V. Sierra, a small proprietor, had been an orphan abandoned to the Casa de Beneficiencia, and Enrique Fournier was a simple laborer. All were veteran officers of the Liberation Army—Ivonnet, Sierra, and Fournier had taken part in the western invasion with Maceo—and all except Sierra were from Oriente.

Nor did the party’s membership include individuals with social or economic leverage. The files of the proceedings against the independientes in April and May 1910 provide valuable information on their social origins. Of the 170 men from all over the island arrested and sent to the Havana jail as suspected independientes, 85 percent belonged to the working class and the peasantry. Most were tobacco workers, peasants, minor employees, unskilled workers, tailors, day laborers, bricklayers, and carpenters. Aside from the leaders, few independientes could be distinguished from the popular classes. There were only seven shopkeepers, three small proprietors, three journalists, two musicians, and one of each of the following: public prosecutor, small factory owner, customs inspector, municipal accountant, police officer, and hacendado. The 170 suspects were balanced across age, with 45 percent of them eighteen to thirty-four years old and members of the postslavery and postindependence generation; 40 percent thirty-five to forty-nine years old, often veterans of the Liberation Army; and 15 percent fifty or more years old, likely to have witnessed or experienced slavery. None was registered as African-born or as a former slave, however. Several were unmarried and illiterate.68

The Partido Independiente de Color clearly represented blacks as well as mulattoes. Forty-five percent of the suspects described themselves as black, 52 percent mulatto, and 3 percent white. The figures for blacks and mulattoes roughly corresponded to their overall proportion within the Afro-Cuban population.69 Although independiente suspects differentiated between pardo or moreno when giving their race, their affiliation showed that they all accepted the concept that a raza de color was more important than the differences between black and mulatto. This belief is particularly significant, because blacks and mulattoes sometimes belonged to separate social clubs, a custom that the Partido Independiente de Color opposed.70 It indicated an ethnopolitical consciousness transcending social practices, a consciousness forged in the postslavery struggle for equal rights and in the independence wars, and emerging from common experience of racism.

In addition, though they were not conceded new rights by the independientes and were ignored by the upper-class white Cuban feminists,71 some Afro-Cuban women actively supported the black party. In several towns, they organized women’s committees of the Partido Independiente de Color. In Matanzas, according to Previsión, women encouraged their husbands and brothers to join the independientes.72 From Cruces (Santa Clara), Manuela Labrado y Garcías congratulated the founders of the party in these terms: “Ah! If I represented by myself the ‘Black’ race and if I wore trousers instead of a skirt, I would not hesitate a single instant to cast my vote for you. Proceed serenely in your endeavor, and perhaps at the end we will raise our victorious heads and we will see our efforts accomplished. This is all I desire for the future of our race.”73

The expansion of the Partido Independiente de Color into a party of several thousand members, the growing Afro-Cuban racial consciousness, and the new militancy of Previsión suggested an escalation of the independientes’ struggle and threat to the social order. In the short term, the threat was only political, aimed at the Liberals of Pres. José Miguel Gómez. If the miguelistas had lost part of their reserve of Afro-Cuban votes to the independientes, the electoral balance would have been tipped in favor of the zayistas or the Conservatives. But the nascent Cuban two-party political system would have withstood that damage. It would have taken years of mobilization before the independientes could break through and bring about the election of enough representatives to influence local or national policies. In addition, their ideology was not “revolutionary”: it did not advocate a complete undoing of the structure and power in society, much less a black or a socialist revolution.

In the long term, however, the Partido Independiente de Color posed a third-party threat and attracted important sectors of formerly Conservative and Liberal Afro-Cuban voters, likely to create a new network of patronage for public jobs. Since most of its leaders were from Oriente, it could well have led to a stronger influence of the eastern province in national politics. More important, the independiente reformist program challenged the very bases of Cuban society. The “rightful share” demanded by the party threatened to change the class structure and the patterns of power, wealth, and income distribution and to allow upward mobility to the Afro-Cuban minority. The positive image of blacks and mulattoes promoted by independientes sharply opposed contemporary dominant racist theories and thus threatened some fundamental assumptions of white society. The party’s claim that Afro-Cubans should be recognized as a full element of the Cuban people and should be allowed to represent Cuba in foreign politics on an equal basis with whites had the potential to alter Cuba’s relations with the United States, the Caribbean, and Spain. Moreover, the virulent independiente campaign against racial discrimination revealed that Afro-Cuban expectations dating back to the independence wars had not been silenced by the vague equality guaranteed by the constitution. Many rejected the proviso that they should stay “in their place” and were ready to resume the struggle for their “rightful share.”

For the first time since the efforts of the Directorio Central de las Sociedades de la Raza de Color in the early 1890s, an Afro-Cuban organization fulfilled the conditions for a subordinate group to act effectively for change. The Partido Independiente de Color articulated individual Afro-Cuban frustrations into collective discontent. It stated that the condition of blacks in Cuba was unjust, and it established new standards of distribution of wealth and power according to which the social contract needed to be renegotiated. Its political message profoundly challenged the dominant ideology, including the myth of racial equality. And last but not least, it comprised a nationwide independent structure capable of competing with mainstream political parties. Such organization violated the taboo of black political separatism for the first time in Cuban history. Whether the white political elites would permit the interests of Afro-Cubans to be represented separately in the elections and to have access to an autonomous network of patronage would really show the extent to which they were ready to fully transform the colonial structures of Cuban society.