Chapter 5

The Breakdown of Reactionary Despotism in El Salvador

Transition toward What?

In January 1979, General Carlos Humberto Romero took a trip to Mexico City. Romero’s situation was desperate, and he was attempting to polish up his tarnished international image, break the increasing isolation of his government, and seek guaranteed delivery of twenty thousand barrels per day of Mexican crude. Seldom has a political trip undertaken by a Latin American head of state turned out as disastrously as did Romero’s. The reception of his hosts was cool, and he could get only a tentative agreement on oil delivery. Worst of all, the details of a report on the situation in El Salvador by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights were leaked to the press in Mexico City during his stay. He was bombarded at a press conference with questions about the report. Romero averred that ORDEN was a “civic association” created to defend El Salvador’s democratic institutions, and he maintained that his government held no political prisoners. Nobody believed him. To add to his distress, the FAPU occupied the Mexican embassy in San Salvador during Romero’s trip, attracting additional international attention to the domestic situation.

President Romero’s visit coincided with a visit to Mexico by Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero, a leading critic of the military government, who was attending a meeting of the Latin American Conference of Bishops (CELAM) in Puebla. The archbishop had just been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, and the contrast between the two men was not lost on observers. The trip may have convinced General Romero that he would have to make some changes if he wanted to remain in power. In February he relented to pressure and repealed the Public Order Law, announced a series of reforms that were completely out of line with his previous record and personal inclinations, and replaced the head of the national guard, Colonel Ramón Alvarenga. This apparent “rectification,” however, may have had more to do with a pending loan application with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) than with any desire to seek reconciliation with those who sought a democratic solution to El Salvador’s troubles. Repression continued unabated, and Romero may have been trying merely to mollify critics in the Carter administration and to make the job of his foreign minister, Antonio Rodriguez Porth, a little more bearable. In a convenient turnabout of the enthusiastic support it gave to the Public Order Law in 1977, the Asociación Nacional de la Empresa Privada (ANEP) also began to call for a “rectification of past errors.”

Labor grew more militant. In March, La Constancia and La Tropical soft drink bottling plants, which belonged to the Meza Ayau family, were occupied by workers. This was the first in a series of labor conflicts that the government tried to suffocate with its repressive apparatus. On 20 March a sympathy strike organized by the workers of the Río Lempa hydroelectric plant (CEL) virtually paralyzed the country, at a cost of $24 million. However, the few decisions rendered by labor courts that went in favor of the workers were ignored by management.1 Labor tensions reached a critical juncture in August. Management started to shut down plants, and some transnational firms abandoned the country altogether.

In early May the BPR occupied the French, Costa Rican, and Venezuelan embassies, as well as the Metropolitan Cathedral. The Bloque was seeking the release of five of its leaders who had been taken into custody and “disappeared.” On 8 May police opened fire on a peaceful demonstration outside the cathedral, killing twenty-three persons. This prompted a scathing attack on the government by Archbishop Romero, recently returned from a visit to Rome.

In an attempt to engage the moderate opposition in a “dialogue” with civilian members of the government, like National Assembly chairman Leandro Echevarría and Minister Rodriguez Porth, Romero lifted the state of siege on 24 July. Earlier in the summer, Echevarría had visited Washington, where he had a breakfast meeting with President Carter to discuss a formula for “decompression.” But Romero refused to meet the conditions of the opposition, which included the dissolution of the death squads, a general amnesty, the return of exiles, an end to repression, and, in sum, a return to the rule of law. Neither the PDC, the main quarry in Romero’s campaign, nor the church hierarchy participated in the “dialogue,” which was confined to a caucus that included the ANEP, the Salvadoran Industrialists’ Association (ASI), the Chamber of Commerce, and the Bar Association.

The fall of Anastasio Somoza, on 17 July 1979, marked a turning point in the Salvadoran crisis. Shortly thereafter, Romero’s government began to disintegrate. Having failed in the attempt to bring the PDC and the more progressive sectors of the bourgeoisie together, the United States increased pressure on the Romero administration and began to seek an alternative to the faltering general. In late July, Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs Viron Vaky flew into San Salvador for secret talks with government officials. Apparently, Vaky made no effort to contact any opposition figures other than representatives of the PDC. U.S. Ambassador Frank Devine revealed the concerns of the Carter administration with a direct allusion to the need “to avoid a repetition of the tragic events that had occurred in Nicaragua.” Deputy Assistant Secretary of State William Bowdler visited the country in August for follow-up discussions, but Romero remained steadfast, stating that his government enjoyed the confidence of the private sector and offering, as his only concession, to allow the return of exiles. In September, Assistant Secretary Vaky went before the House Inter-American Affairs Subcommittee and testified that El Salvador might be near insurrection, a view which was shared by a representative group of Salvadoran intellectuals.2

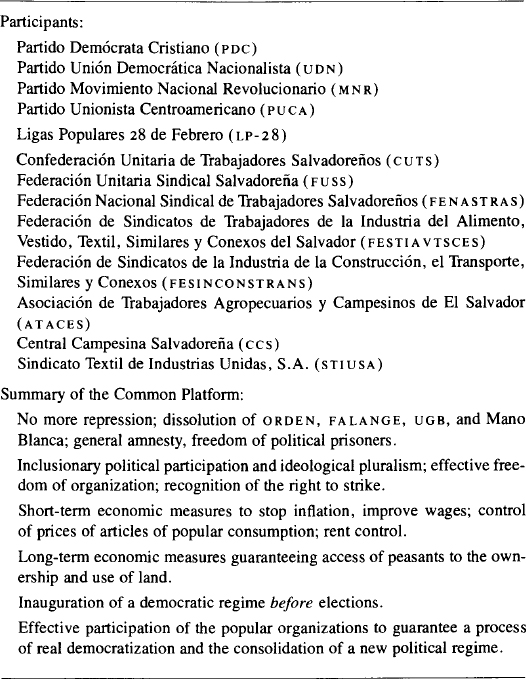

In August, following the failure of Romero’s attempt at dialogue, the opposition organized its own caucus, the Foro Popular, which attracted the participation of an impressive array of organizations of different ideological persuasions (see Figure 5-1). The Foro was significant in that it demonstrated the possibility of an alliance between the moderate petit bourgeois elements of the larger opposition parties and the popular organizations. The platform of the Foro (summarized in Figure 5-1) called for, among other things, a democratic and popular project to find a replacement for the existing system of governance.

The platform could be termed “radical” only from the perspective of the reactionary conservatives lined up behind Romero or of someone totally unfamiliar with El Salvador.3 Flores Pinel correctly points out that the Foro was but the seed of a possible alliance between the middle and lower classes.4 The prospect of such an alliance must have been one of the deciding factors behind the military’s decision to oust Romero, however, since the Foro could have evolved into a grand coalition in the style of Nicaragua’s Frente Amplio de Oposición, which was instrumental in the defeat of Somoza. The Salvadoran military was fearful that such a broad-based and popularly supported group could reorganize the military institution or simply do away with it—as had happened to the Nicaraguan national guard.

But a repetition of the Nicaraguan experience was unlikely. El Salvador had no Somoza, and, therefore, class conflict was a more explicit and ominous component of the struggle there. A unified opposition was still only a remote possibility, and some of the governments that had supported the opposition against Somoza were still studying the Salvadoran situation and waiting to commit themselves. This implies that there was still time for solutions that would have avoided civil war. Finally, the balance of force was overwhelmingly in favor of the government and its paramilitary organizations. All Somoza had was his national guard. In El Salvador, by contrast, the opposition had to reckon with ORDEN and other paramilitary groups in addition to the regular army, and these could not be defeated overnight.

Vaky’s prediction may have been premature, but the Department of State and the Carter administration seemed to share his assessment. The primary concern of the administration seems to have been the prevention of “another Nicaragua.” According to its view the real enemy in El Salvador was a Left that could emerge stronger from a protracted conflict, ready to pick up the pieces of reformist failure and rightist intransigence. This lumped together all the organizations of the Left, ignoring or overlooking differences in their ideologies and tactics, as well as linkages to “middle-class” organizations, that continued to divide them. Perhaps more important, this reading of the situation was shared by the more progressive of the military factions actively involved in conspiracies against Romero.

Concerned with the rapidly deteriorating situation and mindful of the damage that Romero’s continuation in office could inflict on their institutional prestige, different factions of the military competed in their plans to replace him. The officers who staged the coup of 15 October 1979 appeared to be oriented to a progressive solution. They were prepared to address the land question, but they did not deal with the issue of the participation of the popular organizations in the new order that they were advocating.

The Coup and the First Junta

A juventud militar, the junior officers—majors, captains, and lieutenants— organized the coup of 15 October 1979 that brought down the government of General Romero. Theirs was an institutional action different from previous military insurrections and does not appear to have been a preventive coup.5

The military conspirators issued two proclamations on the day of the coup. The first was a formal announcement describing the rationale for the coup. According to this proclamation, Romero had been overthrown by the military institution because (1) he had shown himself unable to deal with the anarchy created by extremist elements, (2) he had repeatedly violated fundamental principles, such as the right of the population to participate in major decisions of national interest, (3) he had persisted in the use of violence to deal with political problems, and this was leading to a confrontation between the “Armed Force” and the people, and (4) he had allowed the public administration to become corrupt. While this rationale voiced the anxiety of the military about its own institutional integrity, the proclamation also promised that the Armed Force would establish the appropriate climate for real and dynamic democracy and would hold free elections.6

FIGURE 5-1

The Foro Popular: Participants and Platform

Source: Estudios Centro Americanos 34, 371 (September 1979); 843-45.

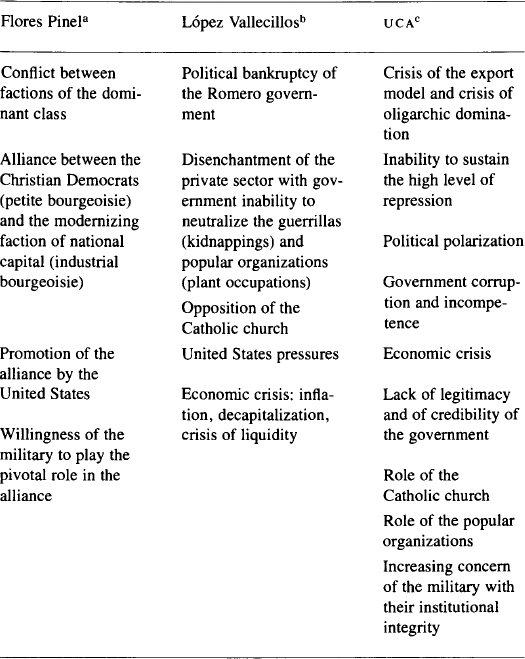

Students of the Salvadoran process have elaborated their own inventories of the reasons that prompted the military coup (see Figure 5-2). Some of these reasons are sociohistorical, namely, the need to form a new alliance between the middle class, represented by the Christian Democrats, and the industrial bourgeoisie, as well as the crisis of an economy based on the export model. The political bankruptcy of the Romero government, representing the attempt to restore the political supremacy of the traditional oligarchy, and the high level of polarization also figure prominently among the immediate causes of the coup.

The second proclamation of 15 October indicates that the military was hoping to implement a reformist program. It proposed first to stop violence and corruption—by dissolving ORDEN and eradicating corrupt administrative practices. Second, it promised to guarantee human rights—creating the climate for free elections, allowing the organization of political parties of all ideological stripes to strengthen the democratic system, granting political amnesty to all exiles and political detainees, recognizing the right of labor to organize, and promoting free speech. Third, it planned for a more equitable distribution of national resources through agrarian reform and a reform of the financial sector that would extend more protection to consumers, promote development programs to create employment and increase national production, and guarantee private property and its social function. Finally, the proclamation promised to implement a more positive foreign policy by reestablishing diplomatic relations with Honduras, strengthening ties with Nicaragua, and promoting better relations with Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Panama.7

Of course too much should not be made of a document of this nature, which must be sufficiently ambiguous to maintain the conspiratorial coalition intact and sufficiently ample and specific to attract as much support as possible from different sectors of the public. Yet the second proclamation is a useful benchmark for the initial objectives of the Salvadoran transition process that began on 15 October 1979.

Of course the implementation of these objectives would provoke a very obstinate and certainly violent resistance on the part of the oligarchy. This reformist platform—which was relatively similar to that of the Foro Popular (see above, Figure 5-1)—was interpreted as revolutionary by the oligarchy. This being the case, it is difficult to imagine how the Provisional Revolutionary Government could have consolidated a coalition that would have included both the popular organizations, considered “subversive” by many in the military, and the oligarchy, which had no interest in the role of “loyal minority” in a democratic regime. On the other hand, given the historical context and the relative weakness of the middle class, the exclusion of the popular organizations and the possible alienation of organized labor would have only made the new center that the military hoped to create more vulnerable to subversion by the oligarchy and other disloyal rightists, including those still in the military. As it turned out, neither the oligarchy nor the popular organizations participated in the first junta or in the Provisional Revolutionary Government. Two years after the coup they remained outside the regime and very much opposed to it, although for very different reasons.

FIGURE 5-2

Causal Factors in the Overthrow of the Romero Government

a. “Golpe de Estado,” p. 894.

b. “Rasgos Sociales,” pp. 876-77.

c. Estudios Centro Americanos 34, no. 372/373 (Oct.-Nov. 1979); 850.

Despite this contradiction the moderate elements in the military seemed to have made an effort to be as inclusionary as possible. The first proclamation appealed to both the extreme Left and the extreme Right to abandon violence and participate in a process in which the Armed Force would guarantee the will of the majority. While these offers were being made, however, the more recalcitrant factions of the military showed, from relatively early in the process, that they were more alarmed by the “extremist elements” mentioned in the proclamation than interested in the conditions for a peaceful transition. Which extremist worried them more was palpable in the harshness with which the security forces dealt with the popular organizations during the first three weeks of the first junta.

The junta attracted the support of a fairly heterogeneous group, including most of the participants in the Foro Popular, with the exception of the Ligas Populares (LP-28). The Foro was represented by Guillermo Ungo and Román Mayorga, a former president of the Universidad Centroamericana Simeón Cañas (UCA). Both men had relatively good relations with the popular organizations and wanted to include them in the government’s blueprint for transition. The more progressive element of the private sector was represented by Mario Antonio Andino. The two other members of the first junta—and undoubtedly the most influential—were Colonel Adolfo Arnoldo Majano and Colonel Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez, identified in the first proclamation as “enjoying the confidence of command vested upon them by the Armed Force.”8 The coalition supporting the junta included the Social Democrats of Ungo’s MNR and the Christian Democrats, reformists from the private sector, organized labor, many technocrats, and the UDN, which had been dominated in recent years by orthodox Communists .9 Although this was a coalition and not an alliance, many of its members had a relatively long history of collaboration in the UNO. The stability and continuity of their participation depended upon the depth of the military’s commitment to the reform program, which Colonel Gutiérrez believed impossible to “be carried out in one day,” and upon the government’s ability to prevent systematic abuse of human rights.10

The first junta and its supporting coalition moved relatively quickly to put together and implement the reform package contained in the second proclamation and in the Foro platform. On 6 November 1979 the junta issued Decree No. 12, disbanding ORDEN and rendering illegal any action taken in its name.11 Decree No. 9, issued on 26 October, had organized an independent Special Investigative Commission to look into the thorny question of the “disappeared,” and produce a complete account of the whereabouts of those persons.12 The junta’s success in dealing with this extremely sensitive issue would be used by many, including the popular organizations, who had been the recipients of much of the repression during the Romero era, as a measure of the willingness and ability of the provisional government to restore a state of lawfulness to El Salvador. An uneasy truce arranged by Ungo and Mayorga prevailed between the government and the popular organizations at the time; the latter were waiting to see the outcome of the investigation of the Special Commission.13

The first junta also addressed the socioeconomic issue. The existing statute of commercialization and price regulation was amended by Decree No. 14 to give more muscle to the fight against inflation, and the minimum wage was increased for jornaleros (day laborers) working in the sugar and cotton harvests of 1979-80.14 More important, Decree No. 43 froze all holdings over 100 hectares—about 247 acres—until a new agrarian statute could be enacted.15 This meant that title to those farms could not be altered, whether by inheritance or commercial transaction. In addition, Decree No. 75 nationalized the coffee export trade and created a new organization, the Instituto Nacional del Café (INCAFE), to assume the functions of the Compañía Salvadoreña de Café (COSCAFE).16 Agriculture Minister Enrique Alvarez Córdova went on national television to defend the decrees and explain the government’s rationale for agrarian reform. Alvarez made a very simple point: 99 percent of the 280,000 agricultural proprietors in El Salvador shared 51 percent of the land, while 0.7 percent held 40 percent of the land.17 In a letter to his subordinates the minister pledged a continued effort to break with this past.18

The intentions, therefore, were good, and the commitment was real. But the ability to implement these measures was lacking. For example, the minister of the presidency, Rubén Zamora, could not really bring about the dissolution of ORDEN because he lacked the cooperation of senior military officers connected to the Romero administration who had managed to survive the coup and were now entrenched in the security apparatus. The measure was also resisted by local comandantes of the national guard. These had traditionally served the interests of large landowners, and some were now engaged in a campaign of violence and intimidation.19

The popular organizations remained very apprehensive. The BPR charged that the coup was an autogolpe (preventive coup) orchestrated by Yankee imperialism and the bourgeoisie.20 The LP-28 suspected the junta since it had taken power “behind the backs of the people,” who had every right to doubt the sincerity and intentions of the junta.21 The FAPU viewed the coup as the result of class contradictions and denounced it as an attempt by the State Department to form a coalition between the aperturista faction of the bourgeoisie and the moderate parties and to leave intact the repressive organs of the state.22 This intransigent rhetoric connotes a somewhat simplistic appraisal of the very complex, unstable, and difficult relations between the armed forces, the juventud militar, the junta, and the security apparatus, but the popular organizations had reason to complain: the level of violence directed against them exceeded that reached under Romero.23 Even commentators sympathetic to the junta concurred in this appraisal and voiced their disapproval of the manner in which the workers occupying the Lido, Arcos S.A., Duramás, and Apex plants had been maltreated.24

Judging by this evidence, one can assume that the leadership of the security apparatus was still in the hands of hard-liners who could not be controlled or who were acting with the at least tacit approval of some government officials. Apparently, these elements coalesced around the defense minister, Colonel Guillermo García, who reportedly had authorized the use of army units to attack mass demonstrations and break up labor conflicts in the cities. Ambiguity about whether these actions constituted “official” policy or not could only be tolerated for a while by the Left. The truce could last only as long as the government was perceived as trying to bring the Right under control.

Colonel García, who had been brought into the coalition at the last moment, was the “swing man” between conservative and progressive officers. García, and his deputy, Colonel Nicolás Carranza, represented, if not the hard-line element within the junta, at least the determination not to allow the Left to derive any advantages from reform—the same mentality displayed by Molina in his proclamations on the Agrarian Transformation of 1976 and made explicit in the proclamations of 15 October 1979.

Presumably, the moderate officers loyal to Colonel Majano, a member of the junta and a leader of the conspiracy, shared the colonel’s desire to build bridges to the Left. They were handicapped in this, however, by their poor connections with and lack of control over the intelligence services of the armed forces. Foremost among these was the ANSESAL, which controlled and coordinated the G-2 and S-2 intelligence agencies of the armed forces. This organization was a bastion of national security advocates bent on stopping the Left at any cost. Even though the more notorious collaborators of General Romero had been retired after the coup, the hard-liners retained considerable influence. They could play the card of Communist insurgency to discredit the moderates, and they were quick to remind everyone of the precedent of Nicaragua. Finally, control of promotions and transfers was in the hands of García, as defense minister, and of Colonel Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez, the other military member of the junta.

Thus, the progressive members of the military and their civilian allies had no effective control in the crucial area of abuses by the security forces. The majority of the direct contacts between the “government” and the popular organizations were through a security apparatus—including the intelligence branch of the armed forces, the National Police, the Treasury Police, and the national guard—that was controlled by elements who saw those organizations as the enemy. Furthermore, the question of the desaparecidos (disappeared) could not be resolved without the collaboration of that apparatus, which of course included persons who had been implicated in previous abuses and had reason to obstruct the inquiry of the Special Commission. The commission was frustrated in its attempts to compile a full account, giving leftist opponents of the junta more reason to doubt its legitimacy.

In general, in cases where the military decides to collaborate in a process of transition to a democratic regime, the question of earlier abuses is carefully sidestepped. Seldom, if ever, are officers implicated in such abuses or in any wrongdoings during a period of military rule brought to justice. Even in the most favorable circumstances imaginable, the military is reluctant to allow any inquiry into these matters and is, needless to say, able to prevent an effective and independent inquiry. As a matter of fact, it would appear that a very important component of the bargain made between moderates and hard-liners in the military in these cases is an agreement, tacit or otherwise, that no such inquiry will be forthcoming. Usually, the question of a general amnesty for all political offenses—which is often one aspect in a restoration of a state of lawfulness—is understood to cover cases of military abuse.

In El Salvador, particularly given the situation confronting the country in late 1979, the satisfactory resolution of the issue of the desaparecidos was impossible short of a complete victory of the moderates and the aperturistas over the conservatives and obstructionists. In December 1979 that victory could have come only from an armed confrontation between rival military factions, but neither faction—assuming there were only two, which is not entirely realistic anyway—was really interested, since both realized that this would imperil the integrity of the military institution. In addition, many officers felt that the guerrillas were also to blame for acts of violence and that if these went unpunished, there was little they could do to sell to their colleagues the need to satisfy the popular organizations on this score.

The inability of the junta to resolve the issue of the disappeared was interpreted by the Salvadoran Left as a clear sign that the moderates were not in full control. The Left may or may not have been willing to maintain its distance from the junta and allow the program of reform to get started. But the fact remains that the obstructionists were determined to stop not only the inquiry but the very process of transition itself and to make sure that the Left was not given any participation in the process. Violence against the Left was the issue that, more than any other, contributed to the polarization of opinion within the government and that finally led to the collapse of the first junta.

On 7 December 1979 a group of government ministers, justices of the Supreme Court, and directors of state enterprises confronted the junta with the demand for a clear definition of objectives that would state the antioligarchic aims of the revolutionary government and a halt to the ongoing repression of “extremists” aimed exclusively at the Left.25 On 28 December the demand was made again in an ultimatum to the Consejo Permanente de la Fuerza Armada (COPEFA), an armed forces council which represented the officers and served as a mechanism of consultation on major policy questions. The COPEFA was asked to respond by 30 December.

Reading the document prepared by these moderate civilians, one can understand the difficult predicament in which they found themselves. They very candidly admitted that their participation in the new government had been based on “the conviction that the juventud militar had sufficient military power to implement their own proclamation [and on] the possibility of incorporating the people to the process.”26 In an allusion to their 7 December demand, which had been addressed to the junta, the signers of the ultimatum declared that they had reached a consensus on the reasons for the shortcomings of the government. They stated that a change had taken place in the command structure of the military which had displaced many of the initial participants in the movement and had allowed the defense minister and some of the garrison commanders to exercise their powers independent of the junta. As a result of this, they charged, the process of transition had made a turn to the right.27 To rectify this departure from the original intentions of the movement they asked the COPEFA to issue a public statement identifying the oligarchy and its allies as the more fundamental enemies of the process of transition and to support the following proposals:

(1)that the junta really assume the leadership of the Armed Force;

(2)that the COPEFA become the only intermediary between the Armed Force and the junta;

(3)that any order of the day issued by the Defense Ministry involving personnel changes be approved first by the plenum of the junta;

(4)that the junta be reduced to colonels Majano and Gutiérrez, representing the military, and Mayorga and Ungo for the civilians;

(5)that the army stop intervening in labor disputes;

(6)that a dialogue be opened between the government and the COPEFA, on the one hand, and the popular organizations, on the other, to clarify the aims of the Military Proclamation of 15 October and to lay some ground rules that would avoid further confrontation; and

(7)that the COPEFA publicly endorse a constitutional statute that would establish a legal framework for the process of transition.28

Essentially, the COPEFA was being asked to accept the leadership of the junta and to help remove the obstructionists from the government coalition, to assume the leading role within the armed forces, and to sanction a new coalition that would include the popular organizations.

Discounting the specifics of the Salvadoran situation and looking at the behavior of the military institution in cases of peaceful transition to democracy in other countries, this demand may have come too early to allow the aperturista faction of the Salvadoran military to overcome the obstructionists.29 On 3 January 1980 the military responded, arguing that the COPEFA “was not a political organization [and] could not be diverted from its institutional mission by extremist attempts; [the COPEFA] was a special organ created to maintain the unity of all its constituent elements” (emphasis added).30 In essence, this response “passed the buck” to the junta for all matters involving policy, but it was emphatic in asserting that

[the] Proclamation of the Armed Forces does not at any time establish strategic alliances with extremist sectors and clearly enunciates that the structural reforms are aimed to break up the power of the oligarchy, with the intention of benefiting the great majority of the Salvadoran people. . . . [Furthermore] minority extremist organizations, [whether] ultra-right or ultra-left, refuse to participate in and obstruct the [transition] process, [and] must be considered counterrevolutionary, and it is the duty of the people and of its Armed Force to defend their conquest and avoid the destruction of the Republic and, by implication, of the armed institution [emphasis added].31

In late 1979 the military aperturistas could not come to terms with the question of the popular organizations; nor could they create the necessary consensus that would welcome popular participation in the process of transition. Their tactics aimed at putting some reforms in place, thus gradually persuading their colleagues and the Salvadoran people of the seriousness of their commitment. Apparently, they were being outmaneuvered inside the military, and they lacked the strength necessary to confront the hard-liners directly.

On the other hand, a majority of their colleagues in the military followed a moderate line which, in practice, worked to the benefit of the Right. At bottom, this moderation implied an attitude of detachment from “political questions.” The reasons for this attitude among members of this pivotal group must be sought in the atavistic nature of contemporary Salvadoran politics, in the relative simplicity of military attitudes regarding “political” issues, and in four decades of anti-Communist rhetoric. Moreover, there was the ever-present concern with the integrity of the institution. They seemed more willing to take their chances with the existing arrangement than to run what they perceived to be the greater risk of collaborating with (leftist) “extremists.”

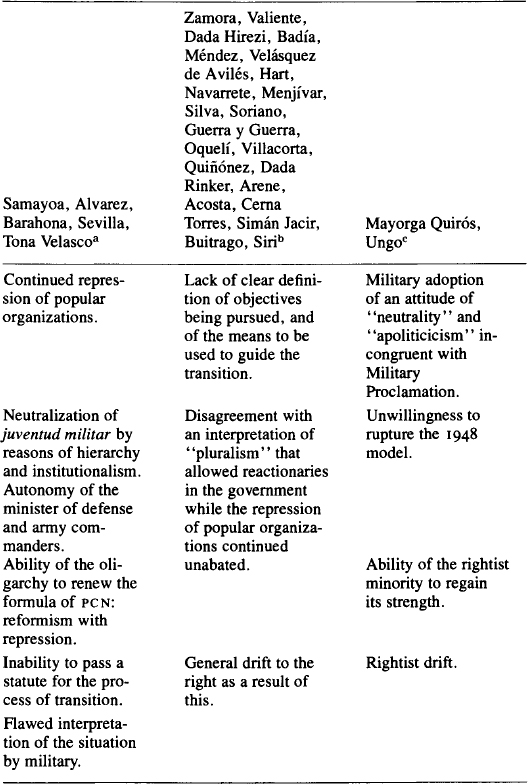

The COPEFA’s refusal to change the status quo and redefine its role brought about a major reshuffle in the governing coalition that witnessed the exit of the Social Democrats. The reasons submitted by departing government officials underscored their desire to give definition and content to the process of transition (see Figure 5-3). The timing of their ultimatum was obviously related to their inability to resolve the question of the disappeared, to what appeared to be a campaign mounted by the Right to win the “battle of the streets,” and to the increase in rightist terrorism. Viewing, as they did, the incorporation of the popular classes in the process of transition as a top political priority, these officials were in a position with respect to the popular organizations similar to that in which military moderates found themselves with respect to their civilian allies. They could promise, but they could not deliver, at least on the question of the protection of basic rights.

It would be a mistake to consider the men who abandoned the government in January 1980 an inexperienced group of idealists or “fellow travelers.” Most of them had paid their dues in Salvadoran politics and subscribed to Social Democratic or Christian Democratic principles.32 They may have made a tactical mistake in trying to produce a confrontation with the obstructionists at a time when they did not hold a sufficiently strong hand, but they were essentially correct in trying to consolidate the transition process in a new coalition that would include the popular sector. Their inclusionary model held more promise for democratic stability than did a new attempt to reequilibrate the regime under an elitist solution or an additional dosage of repressive reformism. Their formula excluded rightist participation in the government— but not in the political arena. This reflected their clear understanding of the role that the oligarchy had played in Salvadoran politics since 1948, derailing every attempt to bring about socioeconomic reform and a peaceful transition to democracy.

The Attempt to Stabilize the Transition Process

The former mayor of San Salvador José Napoleón Duarte, considered by many the most astute Salvadoran politician of his generation, may have made a mistake in accepting the military offer for the PDC to become the government. His party had lost much of its mass appeal, and although he could extract some concessions from the military, he could not force the aperturistas to weed out their obstructionist colleagues, especially after the crisis of the new year. The military proclamation of 9 January 1980 can be read as a concession to the Christian Democrats, and as a late response to the Social Democratic ultimatum. This proclamation reaffirmed the military’s commitment to the goals of the first two proclamations, but it was much more specific concerning the reforms that the government was contemplating. These ineluded the nationalization of banking and foreign trade, the unionization of peasants, and a constitutional statute for the transition period. The January proclamation also admitted the need for a dialogue with the popular organizations in order to include them in the process and suggested that the crisis of the new year had clarified the need to be more specific about the objectives of the Salvadoran transition.33

FIGURE 5-3

Reasons for the First Cabinet Crisis

Source: Texts published in Estudios Centro Americanos 35, no. 375/376 (Jan.–Feb. 1980), as follows: a. pp. 120–21, b. pp. 121–22, c. pp. 122–23.

On 10 January a new junta was formed with the addition of two prominent Christian Democrats—Héctor Dada, who had just resigned as foreign minister, and Dr. José Antonio Morales Ehrlich, the president of the PDC—and a third civilian, Dr. José R. Avalos. The larger presence of the PDC in the revolutionary government was not exactly welcomed by those sectors of the “loyal” Right that the United States had hoped could establish a closer collaboration with the junta. The industrialists’ association (ASI) complained that the PDC had managed to exclude the private sector from the new junta,34 while the foremost association of the private sector, the ANEP, disputed the PDC’S claim that it represented a majority of Salvadorans, dismissing it as “gratuitous.”35 On 20 January the ANEP cut all formal ties with the government. The PCN may have outwitted itself in describing the cabinet crisis as “the fall of the Foro [Popular] government” and as a maneuver instigated by the Communist-controlled UDN to radicalize the process of transition.36 Chafing for being left out of the new government, the ASI, the ANEP, and the PCN continued their virulent attacks on the PDC throughout February.37

The reaction of the Left was equally bombastic, but it led to more visible changes in tactics. On 11 January the three popular organizations—the BPR, the FAPU, and the LP-28—and the UDN issued a joint communiqué calling for unity and armed insurrection.38 That very week they announced the creation of an umbrella organization, the Coordinadora Nacional, which later became the Coordinadora Revolucionaria de Masas (CRM). The Coordinadora produced a programmatic platform which was made public on 28 February.39 In a lengthier document the PCS, the FARN, and the FPL announced the formation of “an organism of revolutionary coordination” between their national directorates, called for a popular revolution, and invited “honast members of the military” to join in the people’s struggle.40 The MNR, for its part, welcomed the unity of the popular forces and maintained that senior officers had derailed the revolution and reimposed repressive reformism.41

The extreme Right saw things differently. On 8 February, Chele Medrano issued his own version of what constituted the gravest aspect of the crisis: Communist subversion. Unveiling previously undetected skills as a constitutionalist, Medrano argued that the junta had no power to decree a constitutional statute and that only a constituent assembly could reform the constitution—the same one he had ignored during his tenure as commander of the national guard.42 Joined by the rising star of the Salvadoran Right, former intelligence chief Major Roberto D’Aubuisson, who had strong ties to the UGB paramilitary group, Medrano organized the Frente Democrático Nacionalista (FDN) and presented himself as the champion of the small agricultural proprietor. In reality, though, the FDN, like Medrano’s previous party, the FUDI, was an outlet for disloyal reactionary conservatives like those represented by the Frente de Agricultores de la Región Oriental (FARO). Both Medrano and D’Aubuisson were the focus of constant speculation about a rightist coup, although they seemed to have drifted apart later on.

Once in power the Christian Democrats proved equally incapable of bringing the security apparatus under the control of the government. For example, on 22 January 1980 the Coordinadora staged a march in San Salvador. Although estimates of the size of the crowd vary, the Coordinadora seems to have exceeded the number of people put on the street by the Right in its Paz y Trabajo demonstrations of December 1979. As they approached the National Palace, police opened fire on the leftist demonstrators, killing twenty-four persons.43 On 19 January, D’Aubuisson had joined the Frente Amplio Nacional (FAN), an organization of very conservative businessmen, in denouncing the purposes of the Coordinadora demonstration and asking “patriotic Salvadorans” to obstruct it.

On 25 February, Attorney General Mario Zamora, a PDC member and the brother of the recently resigned minister of the presidency, Rubén Zamora, was assassinated by right-wing terrorists. Major D’Aubuisson had accused Zamora of being a member of the FPL. Zamora had been trying to get the stalled inquiry into the disappeared moving again. His assassination worsened an internal crisis which had been brewing within the PDC concerning the party’s collaboration with the military, the proper attitude toward the Left, and the pace and substance of the reform program. Before Zamora was murdered, Archbishop Romero had urged the Christian Democrats to withdraw from the government. The murder and the exhortations of Romero led to the resignation of several leaders from the government and the party and to the formation of a splinter group, the Movimiento Popular Social Cristiano (MPSC). Their basic grievances were very similar to those proffered by the Social Democrats when the latter abandoned the first junta.44 The resignation of Héctor Dada brought Duarte into the junta.

On 19 February, Archbishop Romero had written to President Carter to ask him to reconsider his offer of $50 million to the junta.45 Responding on behalf of the president, Secretary of State Cyrus Vance argued that the junta had proven to be moderate and reformist, that most of the aid was economic, and that the United States would make sure that the military aid would not be misused in the violation of human rights.46 In his Sunday homily of 23 March the archbishop asked soldiers not to fire on their brethren. On 24 March, while saying late-afternoon mass, Romero was assassinated. On 30 March police and army units opened fire on a crowd of about eighty thousand gathered at the Plaza of the Cathedral in San Salvador for Romero’s funeral. The government blamed the Coordinadora Nacional for the incident, but foreign bishops attending the funeral declared that soldiers positioned nearby had fired first.47

These incidents diminished the legitimacy of the government and eroded its popularity. To be sure, the PDC condemned rightist terrorism,48 deplored the disruption of the 22 January march by the Coordinadora,49 and launched what it claimed was a vigorous investigation into the assassination of Romero. Shortly thereafter, however, Judge Atilio Ramírez Amaya, who was in charge of the investigation, was himself the target of an assassination attempt, and he left the country.50 Data compiled by the Salvadoran Commission on Human Rights, the Socorro Jurídico of the archbishop’s office, and the press office of the archbishop showed that between 1 January and 13 March 1980 a total of 689 political assassinations had been perpetrated.51

One wonders why the PDC agreed to assume so much responsibility with so little power, and in a country moving toward civil war. To put the best face on things, perhaps the PDC leadership believed that it could prevent the situation from worsening, as it certainly would have if the Right had gained control of the government. Supported by the United States and Venezuela, the PDC leaders sought to consolidate their position with that of their aperturista allies in the military. If they could then effect some reforms, they could increase the credibility and legitimacy of the government and try to bring the Social Democrats back into some kind of collaboration with the government. Finally, after waiting for the appropriate opportunity, they could provoke, and win, a confrontation with the Right.

This scenario had one great flaw, however. A party, and the government that it organizes, cannot show itself unable or unwilling to stop indiscriminate killings by its security forces for a long period of time without having to share moral responsibility for such actions. Neither the PDC nor the military aperturistas could hope to gain enough leverage vis-à-vis the Right without a very strong show of popular support. But as we have seen, Majano and his supporters hesitated too long on the question of popular participation in the new government, they wasted time while their power base was eroding, and they were unable to risk an alliance with the popular sectors. In what was rapidly becoming an undeclared civil war, the disruptive capability of the Right could be matched only by the numerical strength of the popular organizations or by the unequivocal support of the military for the process of transition. And the PDC could count on neither of these in March 1980.

Yet Duarte had been unwilling to support his legitimate claim to electoral victory in 1972 with an appeal for a popular uprising. In addition, he had refused to join forces with the military during the crisis of 1960, for this would have tarnished the image of his fledgling party. What were the motives for his decision to make common cause with a former enemy in 1980? How much had the military and Duarte changed to make this possible? One possible answer is that Duarte and the PDC leaders who stayed in the government were anti-Communists willing, within certain limits, to prevent “another Nicaragua.”

A “Machiavellian” explanation of the continued presence of the PDC in the Provisional Revolutionary Government assumes that the party believed that its presence in the government would give both their best chance to resist a rightist onslaught. The party would lose some prestige from its collaboration with the military, but it would be supported by the United States in its efforts to implement reforms, which the military would have to accept as the price of collaboration. In the meantime, while the party recovered its prestige through the implementation of reforms, leftist and rightist extremists would knock each other out and clear the way for the moderates. The coming to power of the Reagan administration may have made this gamble all the more desperate.

The sobering fact is that, despite its failure to control the violence, the PDC managed to push forward a limited yet real program of reforms. Yet without the restoration of a state of lawfulness, the reforms alone could not legitimize the PDC-military junta.

In late February Decree No. 153 was announced. More timid than the draft prepared by Enrique Alvarez under the first junta, this statute for agrarian reform affected only holdings above five hundred hectares, that is, the 25 percent of the land controlled by 244 landowners.52 On 8 March Decree No. 158 nationalized the banking industry.53 This new package of reforms, however, was accompanied by the declaration of a state of siege, on 7 March, which made the undeclared civil war official.54

Later on, when Dr. Morales Ehrlich addressed the nation in a televised appearance to review the accomplishments of the first six months of the Christian Democratic juntas, he would be able to enumerate some important achievements.55 However, the significance and value of these measures were stained by the continuing repression, which the junta was unable to stop. In essence, the Christian Democrats were embarked on reformism under a state of siege.56

The End or the Beginning?

The coup of 15 October 1979 ended the dominance of a system that well fits the model of reactionary despotism described by Spanish sociologist Salvador Giner. Used by him in his analysis of the traditional authoritarian regimes of the Mediterranean area, reactionary despotism is a mode of domination characteristic of capitalist economies that have developed “late,” that is, since World War II. Such governments are monopolized by reactionary coalitions that maintain exclusionary political regimes in which actual or potential opponents are denied basic citizens’ rights. The power of the state is utilized arbitrarily to contain or disarticulate organized opposition, and co-optation and passive obedience replace the active consent of the society.57

Central American regimes that fit Giner’s model display quite a number of important differences. It appears, however, that the core element of the reactionary coalition can be identified. This core element would include the largest agricultural planters, who monopolize the control of sectoral associations, cattle ranchers, large merchants with linkages to agricultural interests, financiers and bankers whose main creditors or factors are engaged in the export trade, real estate speculators, former government officials and retired military officers who used their positions in government to enrich themselves illicitly, and individuals connected to the repressive apparatus, whether official or paramilitary.58

In El Salvador this core group of the reactionary coalition was closely tied to the “magic square” of oligarchic domination of the economy: the monopoly of land tenure, agricultural production, export sales, and finance. If one is to understand the dynamics of the Salvadoran process of transition inaugurated by the October 1979 coup, one important fact must be taken into consideration. Despite the continuation of authoritarianism in El Salvador, the condition of civil war, the continued exclusion of large sectors of the population from the exercise of citizen’s rights, and the division of power between the junta and the military, the governing coalition has changed and some basic aspects of the mechanism of reproduction of capital that characterized El Salvador before October 1979 have come under the control of the state.

The shortcomings of the agrarian reform carried out by the third junta are well known: holdings between one hundred and five hundred hectares have not been touched; the government bureaucracy has had a difficult time managing the logistics of the reform; titles have been slow in coming; and credit has been insufficient. In addition, it remains open to question whether the reform has been truly “redistributive”—as formulated by the late minister of agriculture and FDR leader Enrique Alvarez—or a function of “counterinsurgency”—in the blueprint of Professor Roy Prosterman, a United States agricultural expert responsible for the model of rural pacification in Vietnam.59

Nevertheless, the army moved with tremendous speed to implement the reform. On 4 March 1980 the ISTA was reconstituted, and on 6 March decrees 153 and 154—respectively, the Basic Statute of Agrarian Reform and the transitory dispositions on the appropriation of lands—were passed by the junta.60 These were accompanied by the declaration of a state of siege— Decree No. 155—suspending constitutional guarantees for thirty days. Apparently, those responsible for drafting, announcing, and implementing the decrees had not forgotten the lessons of the crisis that accompanied the ISTA-Agrarian Transformation in 1976, and they acted swiftly. According to a leading critic of the reform of 1980, the oligarchy, “which had become convinced that the dynamics were returning to their favor, were flabbergasted at this unexpected turn of events.”61

There is little question that the enactment of the reform marked a turning point in the countryside, as the paramilitary Right took matters into its own hands to try to frustrate the program. Numerous resignations and complaints followed the upsurge in violence, which began to take its toll among ISTA officials and peasant beneficiaries of the reform. As a matter of fact, passage of this statute may have marked the beginning of the civil war in El Salvador. As far as the largest agriculturalists were concerned, these two decrees, together with Decree No. 43—which had frozen the status of all holdings above one hundred hectares under the first junta—were a severe blow. They did not solve the land question in El Salvador, but they constituted an important political measure, for they weakened one of the corners of the square. Another corner of the magic square was also affected by the burst of decrees in early March that marked the entry of Duarte into the government: decrees 158 and 159 of 7 March nationalized banking and savings and loans institutions in El Salvador.62

Unlike the agrarian reform statute, these two decrees could be enforced efficiently and stringently, the oligarchy could evade them only with difficulty, and the PDC could closely supervise their implementation. Judging by the opposition of the private sector to the decrees—which were still in place in late 1981—they must have been relatively efficient in achieving their purpose.

One further encroachment on the prerogatives of the oligarchy had already taken place during the first junta: the nationalization of the domestic and export trade of coffee. This measure had been bitterly resisted by ABECAFE, which disputed “the argument that the concentration of economic power in a few hands is contrary to the interests of the cafetaleros and the country in general . . . because the coffee that we used to export was not ours.”63

It is important to understand and discriminate among the different confrontations going on in El Salvador. This is difficult to do given the profound human drama posed by the catastrophic loss of life, the savagery of some of the killings, the contradictory reports flowing out of the country, the insistence of some on seeing the crisis as a textbook case of Communist interference and the grief of others who dread a repetition of Vietnam, and the natural tendency to reduce the roles of a host of peripatetic actors to a few stereotypes. But this much can be said: the coup displaced the reactionary coalition, and the decrees of the first and third juntas, reviewed above, seriously undermined the economic bases of the core element of the reactionary coalition.

These measures merely decapitated the dominant group, however, and aspirants to succeed it are not in short supply. For example, it is quite possible that those cultivators spared by the reform, with holdings between one hundred and five hundred hectares, could, under the leadership of someone like Chele Medrano, forge a coalition with conservative officers and restore reactionary despotism. It is also possible—and there is considerable precedent for this—that elements of the military could appropriate the land and become a new oligarchy under a facade of “state capitalism.” Meanwhile, as will be made clear by the discussion presented in chapters 6 and 7, the more reactionary elements retain considerable power and have been able to neutralize any alliance between the PDC and the industrial faction of the Salvadoran bourgeoisie.

Reformism under a state of siege did not pacify El Salvador, and the reforms and the prospects for a democratic transition were in dire straits in late 1981. Yet these reforms, though enacted behind the backs of the people, were sufficiently effective to provoke the wrath of the Salvadoran Right. Assuming that these elements would continue their obstructionist tactics, one must ask whose interests were really served by the continued estrangement between Social and Christian Democrats? What additional cost could be incurred by an attempt to form a broader coalition that would include the popular organizations? How could a process of transition to democracy be effected without the neutralization of the rightist obstructionists?

During 1980 and 1981 most of the private sector of El Salvador remained opposed to the government of the Christian Democrats. The position of the aperturistas in the military deteriorated considerably. Duarte remained the formal representative of a state that had acquired more independence vis-à-vis the traditional oligarchy, but his government remained incapable of delivering the key element to legitimize a provisional government trying to implement a transition to democracy. This was the restoration of citizens’ rights. Whatever qualitative changes had taken place in El Salvador, these were overshadowed by a conflagration that had already surpassed the toll of the matanza of 1932. One of the reasons to proceed with a “controlled solution” had presumably been a sincere desire to minimize violence and loss of life, but this could not be treated as a valid reason in late 1981. Perhaps in reality the coup and the controlled solution were first and foremost attempts to prevent a leftist victory. Paradoxically, this solution, this return to repressive reformism, was the situation that had created the problem in the first place.