THE CHILOPODA

THE chilopods are the true centipedes with one pair of legs on each body segment. They, together with the diplopods, pauropods, and symphylans, are distinguishable from the other mandibulate arthropods by the division of the trunk into only two tagmata, a head and a body, wherefore these four orders have been classed together as members of one group, termed the Myriapoda because of their large number of legs as compared with the insects. The chilopods, however, are opisthogoneate, the genital opening being at the posterior end of the body, while the others are progoneate, having the genital opening near the anterior end of the body. Furthermore, it is not certain that the segmental composition of the head in the diplopods and pauropods is the same as that of the chilopods and symphylans; the chilopod head carries two pairs of maxillary appendages behind the mandibles, while in the diplopods and pauropods there is only one postmandibular head appendage. On the other hand, the symphylans resemble the chilopods in having two maxillary appendages on the head, and in this respect these two groups are like the insects. But again, the chilopods, the diplopods, and the pauropods have certain head characters not present in the insects, and the mandibles of the diplopods and symphylans have a structure peculiar to these two groups. However, all the myriapodous forms and the insects have one common feature by which they differ from the other arthropods, which is that the pretarsal segment, or dactylopodite, of the legs has only one muscle, which is the usual depressor, or flexor, with its fibers arising in segments proximal to the tarsus. Altogether, then, the inconsistently distributed characters of the seemingly related myriapods and insects make a difficult problem for the phylogenists.

A feature peculiar to the chilopods, diplopods, and symphylans, though not present in all of them, is a pair of sensory organs known as the organs of Tömösvary, situated on the sides of the head a short distance behind the bases of the antennae. The essential part of each of these organs is a group of sensory cells in the epidermis innervated from the optic lobe of the brain. In some forms the sense cells lie at the bottom of a deep open pit, in others they are contained in a small, circular cavity of the cuticle with a central aperture, in others the cuticular cavity is horseshoe-shaped with a median cleft to the exterior, again the cavity is an oval groove without an external opening, and, finally, the sensory elements may be covered merely by an undifferentiated cuticle. The structure of the organs of Tömösvary in the chilopods and diplopods is described by Hennings (1904, 1906) and by Pflugfelder (1933), that of the symphylan Hanseniella by Tiegs (1940). The function of the organs is not known.

The chilopods are divided taxonomically into four orders, the Scutigeromorpha, Lithobiomorpha, Scolopendromorpha, and Geophilomorpha. The first two are anamorphic, in that the body segmentation is completed after hatching; the other two are epimorphic, their segmentation being complete when they leave the egg. The chilopod structure will be best understood by a study of a representative of each of the four orders.

SCUTIGERA

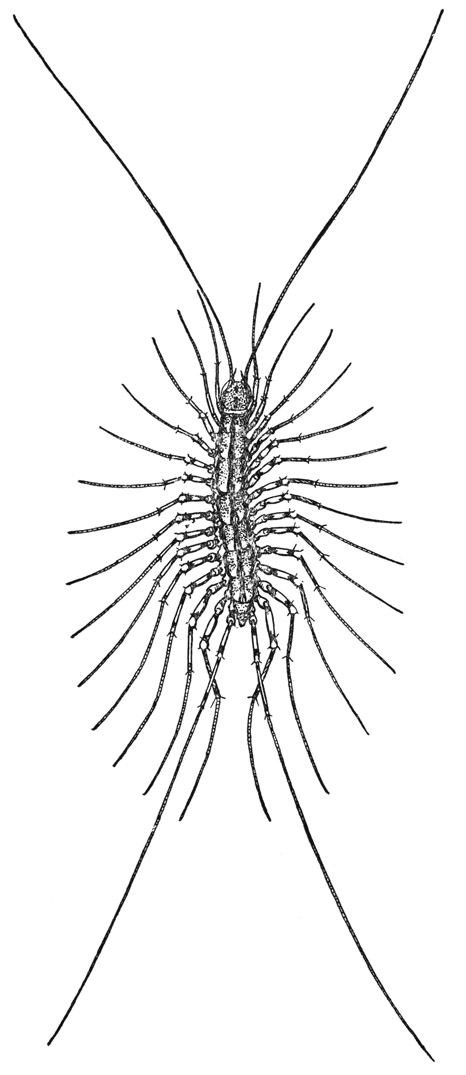

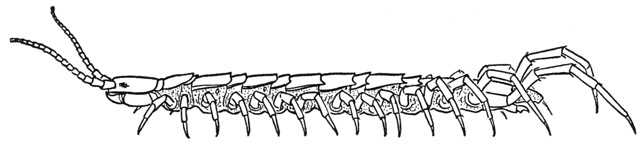

Scutigera coleoptrata (L.) is the common “house centipede” (fig. 52), so called because it is more frequently found in houses or other buildings than out of doors. Scutigera is the typical genus of the subclass Scutigeromorpha, which includes about 14 genera in the single family Scutigeridae. The members of this group differ in one remarkable respect from the other centipedes in that their breathing orifices are on the middle of the back, where each opens into a bilobed, lunglike tracheal respiratory organ, while in the other chilopod groups the spiracles are on the sides of the animal and open into tracheal tubes that branch throughout the body. For this reason the scutigerids are sometimes classed as Notostigmata and the rest of the centipedes as Pleurostigmata. The pleurostigmatic centipedes live mostly on the ground under stones and logs, or beneath loose bark, but such confined places would not be suitable to the scutigerids with their spiracles on the back. The Scutigeromorpha, therefore, live in more open places, and Scutigera coleoptrata, when it invades human dwellings, never seeks to hide itself beneath any loose object but depends on its speed to escape capture, in which it is usually successful.

Fig. 52. Chilopoda. Scutigera coleoptrata (L.). The house centipede.

The house centipede (fig. 52) is easily recognized by its long slim legs crowded along the sides of the body, its much longer, threadlike antennae, and its equally long and slender hind legs. The head (fig. 54 A, B) carries dorsally the eyes and the antennae; on its underside are the mandibles, a pair of first maxillae, and a pair of second maxillae. Immediately behind the head is a much reduced first body segment, which has a very small tergal plate (A, 1T) but carries the huge poison claws, or maxillipeds (Mxpd). Following the poison claws are 15 pairs of legs, between which on the ventral surface are 15 simple sternal plates overlapping from before backward (fig. 53 E). On the corresponding part of the dorsum, however, there are only 8 tergal plates. The first of these terga (fig. 54 A, 2T) pertains to the segment of the first pair of legs (1L); the next tergum covers the segments of the second and third legs, and the third those of the fourth and fifth legs, but the longer fifth tergum extends over the segments of the sixth, seventh, and eighth pairs of legs; the next three terga again correspond each with two pairs of legs, while the short ninth tergum (fig. 53 A, 9T) belongs only to the segment of the fifteenth pair of legs (15L).

Behind the last leg-bearing segment is a well-developed legless segment, which is the seventeenth body segment (fig. 53 A, B, C, 17), covered by the tenth tergal plate (A, 10T). In the female of Scutigera (B, C) this segment carries ventrally a forceps with two-segmented prongs, or gonopods (Gpd), between which is the genital aperture (C, Vul). In the male (D) the corresponding segment is smaller than that of the female, but on its posterior ventral margin it bears a pair of small, setigerous, styluslike gonopods (1Gpd). A second pair of similar gonopods (2Gpd) is situated on a transverse fold behind the bases of the first pair, which fact suggests that in the male there are two segments in the genital region, though the second is much reduced. There is, in fact, reason to believe that in both sexes of all the chilopods there were primarily two appendage-bearing segments between the last leg-bearing segment of the adult and the apical segment, or telson (Tel), since it has been shown by Heymons (1901) that in the embryo of Scolopendra (fig. 60 H) there are two small segments in this region, each bearing rudiments of a pair of gonopods. Inasmuch as the genital aperture lies behind the second of these segments, when two are present, this segment is called the genital segment (gSeg), and the one preceding, the pregenital segment (pgSeg). Behind the genital segment is the anusbearing telson (Tel).

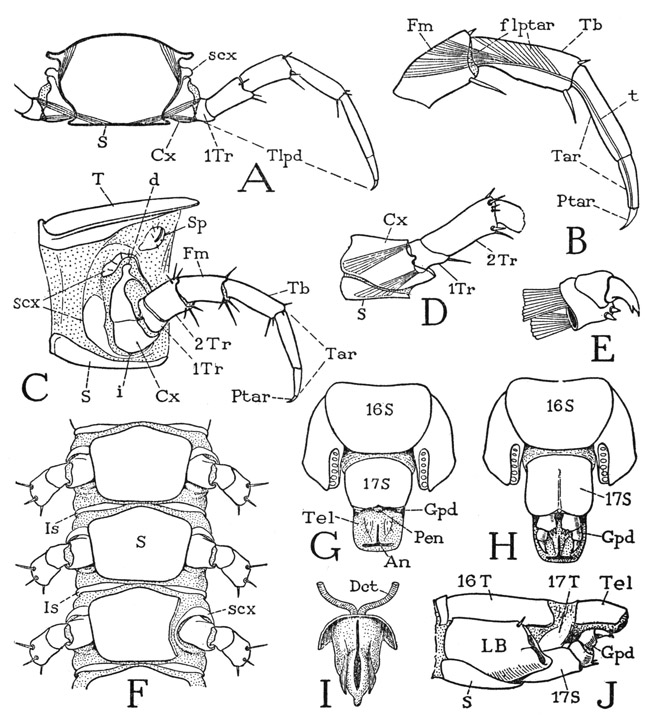

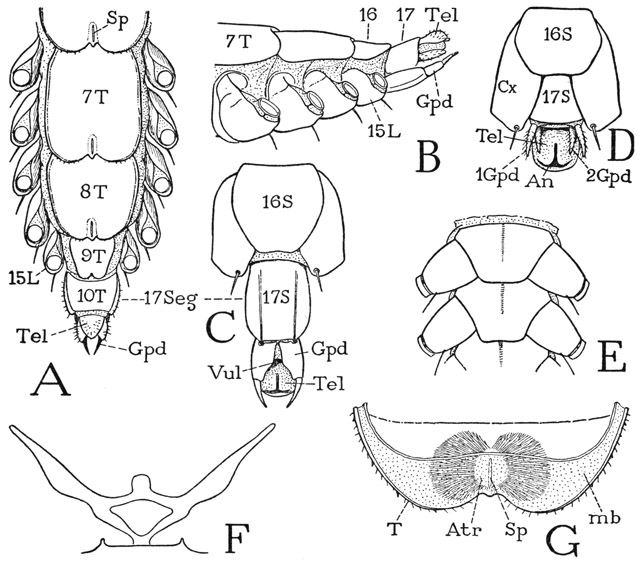

Fig. 53. Chilopoda—Scutigeromorpha. Scutigera coleoptrata (L.). The body segments.

A, posterior part of body of female, dorsal; numerals indicate body segments. B, same segments of female, lateral. C, end segments of female, ventral. D, end segments of male, ventral. E, two consecutive sternal plates, with coxae. F, endosternal arms of sternum. G, pair of tracheal lungs in posterior end of tergum, seen from below through inflected membrane (mb).

For explanation of lettering see pages 223–224.

The eight tergal plates of the 15 leg-bearing segments of Scutigera have rounded, medially indented posterior margins that widely overlap the tergum following (fig. 53 A). Just before the notch on each of these terga but the last is a short, median slit (Sp), which is the aperture, or spiracle, of a respiratory organ (G) that can be faintly seen through the tergal wall. The external aperture (G, Sp) opens into a thin-walled median sac, or atrium (Atr), from each side of which are given off numerous fine, dichotomously branching tracheae, massed in two lateral bodies with such an even contour as to suggest that the whole is covered by a thin tunic; under the microscope, however, no such covering is to be seen. The respiratory organ is virtually a pair of tracheal lungs with a common opening; it is contained mostly in the posterior fold of the tergum closed below by the membranous inflection (mb) from the tergal margin.

The ventral body muscles of Scutigera are not attached on the sternal plates but on an endosternal structure (fig. 53 F) composed of two lateral bars that diverge upward and laterally from a common median support on the posterior end of the sternum to points close to the edges of the tergum. The two bars are connected by a bridge supporting a median membranous lobe on which muscles are attached. This “endoskeletal” structure is not a cuticular ingrowth or apodeme; it slowly dissolves in caustic, and is a tissue entirely similar to that of the intergnathal ligament of the head, on which the ventral muscles of the mandibles and maxillae are attached (fig. 55 B, Lg).

The head of Scutigera (fig. 54 A) differs in several respects from that of the other chilopods. Instead of being flattened, the cranium is strongly convex dorsally; its lateral margins slope downward from the back of the neck to the labrum (Lm). The large eyes are situated laterally behind the middle of the head, and in front of them arise the antennae, separated by a long, steeply declivous epistomal surface (Epst) from the marginal labrum (Lm). On the chilopod head there is none of the familiar lines, or “sutures,” of an insect’s head. In Scutigera coleoptrata (B) a line marking an internal ridge of the cranial wall runs forward and mesally from the inner angle of each eye and is joined to its mate by a reversed U-shaped groove, from which a faint median ridge runs back between the eyes.

The large eyes of Scutigera have superficially the appearance of many-faceted compound eyes such as those of the crustaceans and insects. Internally, however, the eye does not have the structure of a true compound eye. Examples of the structure of myriapod eyes will be given in the next chapter.

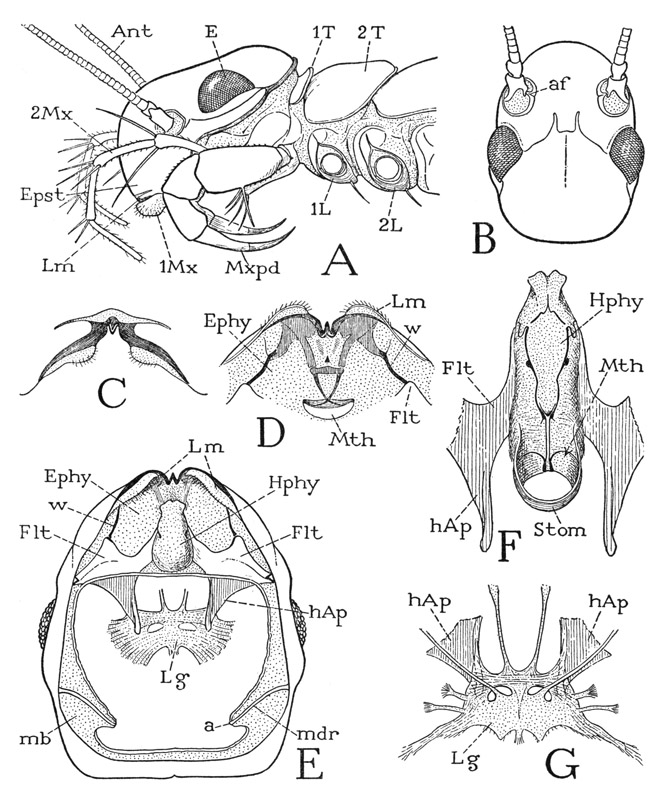

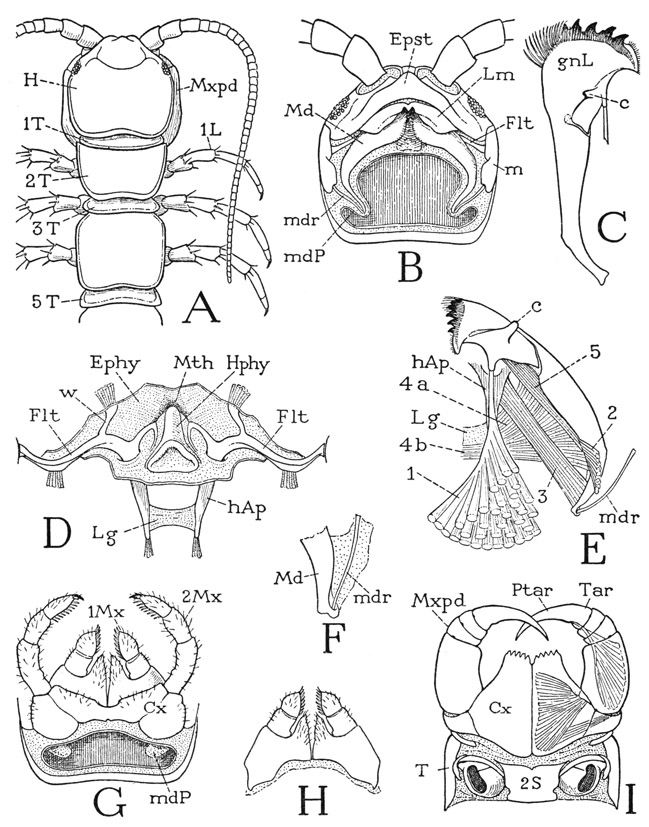

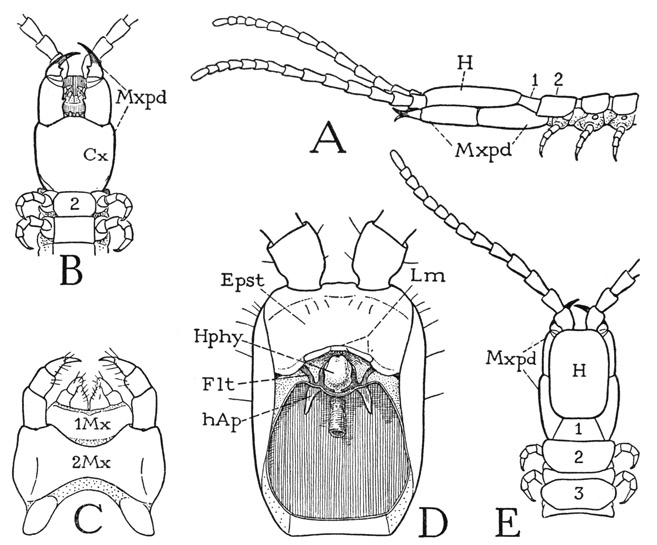

Fig. 54. Chilopoda—Scutigeromorpha. Scutigera coleoptrata (L.). The head.

A, head and anterior body segments, left side. B, head, dorsal. C, labrum, anterior. D, labrum and preoral epipharyngeal surface, ventral. E, head, ventral, mouth parts removed, showing epipharyngeal surface (Ephy), hypopharynx (Hphy), fultural sclerites (Flt) with head apodemes (hAp) supporting intergnathal ligament, and articular rods of mandibles (mdr). F, hypopharynx and adjoining parts of fulturae. G, intergnathal ligament, muscles removed, supported on ends of head apodemes, dorsal.

For explanation of lettering see pages 223–224.

Each long, threadlike antenna of Scutigera is supported on a short basal stalk, or scape, of two small segments set in a membranous depression, or socket, of the head wall and pivoted on a short process, the antennifer (fig. 54 B, af), projecting from the mesal rim of the socket. The antenna as a whole is thus free to swing about in all directions, and it is provided with basal muscles arising on the head wall. The distal part of the antenna, or flagellum, is divided into a great number of short annulations that give it flexibility, but at two points it has true joints that divide it into three segments movable by muscles. As shown by Imms (1939), a dorsal muscle arising in the scape and two ventral muscles arising in the first flagellar segment are inserted on the basal ring of the second segment of the flagellum, three corresponding muscles arise in the base of this segment and are inserted on the base of the third flagellar segment, and, finally, a similar set of muscles traverses the last segment, becoming extremely attenuated toward the extremity.

The labrum of Scutigera is not a free lobe of the head, and is only partly set off from the epistomal region above it by a transverse membranous area (fig. 54 A, Lm). It is marked by two dark bands on the lower margin of the cranium (C) converging to a median notch in which is a strong tooth. On each side of the notch the labrum bears an elongate, soft, setigerous marginal lobe.

The ventral surface of the head is entirely concealed by the mouth parts and the poison claws. Though the poison claws are the appendages of the first body segment, they are functionally associated with the feeding organs and are hence called maxillipeds. In order to conserve material, the appendages, beginning with the maxillipeds, may be studied first, since their successive removal will expose the underside of the head.

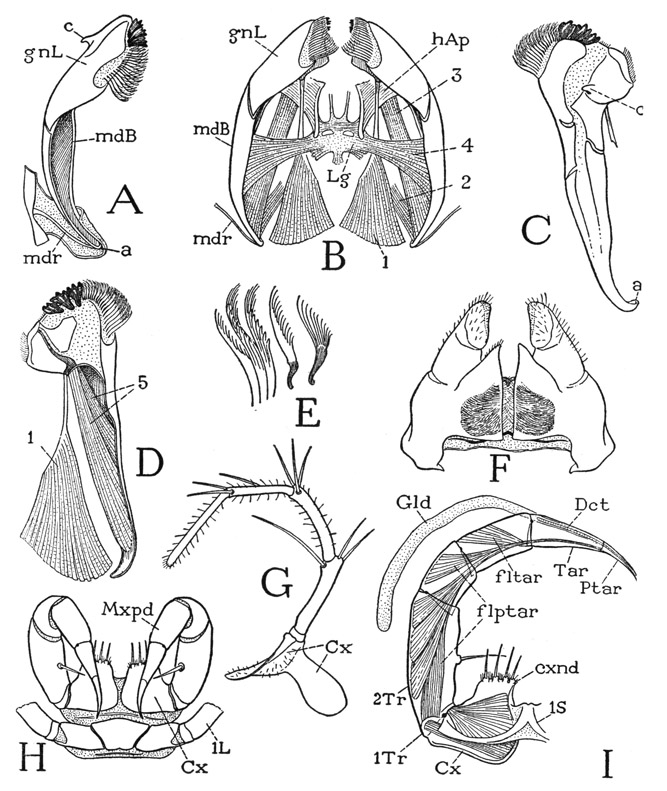

The poison claws, or maxillipeds, of Scutigera are seven-segmented, leglike appendages (fig. 55 H, Mxpd) turned forward at the sides of the head (fig. 54 A), with their distal, clawlike segments curved downward and posteriorly in the manner of a rattlesnake’s fangs. The large flattened coxae (fig. 55 H) arise close together beneath the posterior part of the head, and each is produced forward in a broad endite (I, cxnd) armed with four strong spines. The telopodite of each appendage is attached laterally to the coxa by a small first trochanter (1Tr), which is followed by a long second trochanter, or prefemur (2Tr), a short femur, a tibia, and the long, curved claw. The claw of the poison fang of Scutigera is indistinctly divided into a tarsus and a pretarsus (Tar, Ptar), but in other chilopods these two segments are united. At the tip of the pretarsus is the opening of the duct (Dct) of the poison gland (Gld), which latter is a long cylindrical sac extending back to the middle of the second trochanter. Though the pretarsal claw is not freely flexible on the tarsus, it has a strong flexor musculature; attached on its base is a long tendon that traverses the tarsus and tibia and gives insertion to five bundles of muscle fibers arising in the femur and the second trochanter (flptar). The pretarsus of the maxillipeds, in common with that of the legs in all the centipedes, has no extensor muscle. Each of the other segments of the maxilliped is likewise provided with a flexor muscle, though only that of the tarsus (fltar) is shown in the figure. The poison claws of the centipede are the organs by which the animal captures and kills its prey.

The second maxillae arise in front of the maxilliped coxae and project forward from beneath the expanded basal angles of the first maxillae. Each second maxillary appendage of Scutigera (fig. 55 G) is a slender, six-segmented limb; in no other arthropod does the second maxilla so much resemble a leg. The coxa (Cx) is a large plate with a mesal arm behind the base of the first maxilla and a broad lateral arm extended upward and posteriorly in the membranous lateral wall of the head (fig. 54 A), but with no articulation on the cranium. The five-segmented telopodite constitutes a spiny palpus projecting forward beyond the front of the head.

The first maxillae (fig. 55 F) are thick, soft, triangular lobes showing evidence of not more than three segments. They lie close together against the undersurface of the head, but are not united except as they are connected by two transverse sternal bars of the head wall between their bases. The broad basal parts of the appendages may be supposed to be the coxae, and the tapering distal parts the telopodites, which end with seta-covered lobes that project beneath the labrum (fig. 54 A, 1Mx). Mesally, from the base of each appendage, there project two small endite lobes. The two closely adjacent first maxillae (fig. 55 F) form the functional underlip of the chilopods, which thus differ from the insects, in which the underlip, or labium, is composed of the united second maxillae. In the mesal surface of each first maxilla of Scutigera is a deep pouch from which issues a great mass of long, delicate, filamentous setae. Within the inner part of the pouch, intermingled with the bases of the hairs, are innumerable minute spindle-shaped rods characterized by a fine, spiral surface thickening running left to right from the base almost to the transparent tapering tip. Electron microscope studies of these setae have been made by Richards and Korda (1947), but their structure is visible under an ordinary microscope with a strong light. The pouches are eversible, and the brushes of setae are thought to be cleaning organs; the rods, however, are deeply seated in the pouches and are readily detached.

The mandibles will be fully exposed on removal of the maxillae. They lie longitudinally (fig. 55 B) against the lateral parts of the ventral head wall and are connected with the cranial margins by deeply infolded membranes. Each mandible (A) is elongate, weakly sclerotized, widened at its anterior end, tapering posteriorly, and curved mesally. The broad, free anterior part is the gnathal lobe of the jaw (gnL) and is applied against the side of the hypopharynx. The tapering posterior part, or mandibular base (mdB), is open mesally into the head cavity and gives attachment to the mandibular muscles (B); its narrow posterior end is connected with the cranial margin behind the eye by a delicate rod (A, mdr) in the supporting infolded membrane. The attachment point of this rod to the mandible (a) represents the usual posterior cranial articulation of the jaw, which in the chilopods is intermediated by the rod, thus allowing the mandible a free movement as far as the suspensory membrane will permit. On the laterodorsal surface of the gnathal lobe is an anterior articular process (c), but it merely hooks over a ridge on the epipharyngeal surface of the head (fig. 54 D, E, w) and is hence only a point of loose contact and not a fixed articulation. A line between the two articular points (fig. 55 A, a, c), however, probably gives the mandible an axis for lengthwise rotation.

The walls of the broad gnathal lobe of each mandible contain two principal plates, one ventromesal (fig. 55 D), the other dorsolateral (C), separated dorsally and ventrally by wide membranous areas. Each plate is set off by a nonsclerotized incision or break from the mandibular base, so that the gnathal lobe appears to be flexible on the latter. The ventromesal plate bears distally three large, strong, loosely attached, tricuspid teeth, and on its mesal margin proximal to the teeth a broad fringe of thick, brushlike setae, several varieties of which are shown separately at E of the figure. The dorsolateral plate carries the anterior articular process (C, c).

Fig. 55. Chilopoda—Scutigeromorpha. Scutigera coleoptrata (L.). The mouth parts.

A, right mandible, mesoventral, showing posterior articular rod (mdr) in membrane inflected from edge of cranium. B, mandibles and their muscles, ventral, with intergnathal ligament supported on head apodemes. C, left mandible, dorsal, showing anterior articular process (c). D, left mandible, mesal, with muscles of gnathal lobe. E, brushlike setae of mandible. F, first maxillae, ventral. G, left second maxilla, ventral. H, macillipeds and first leg segment, ventral. I, left maxilliped, dorsal, poison gland displaced, showing muscle of pretarsus.

For explanation of lettering see pages 223–224.

In the normal position of the mandibles (fig. 55 B) the teeth of the distal margins are dorsal, toward the mouth, and the brushes guard the mouth entrance ventrally. The chilopods are reluctant to demonstrate the action of their mouth parts under a microscope, and the only movements of the mandibles to be seen in a live specimen are those of protraction and retraction. Protraction brings the toothed margins of the jaws together, and, as the mandibles are thrust forward, the maxillary lobes slide backward against their undersurfaces.

The musculature of the mandibles (fig. 55 B) consists of extrinsic muscles arising on the head wall, or on the ventral head apodemes (to be described presently, fig. 54 E, hAp), and intrinsic muscles contained within the mandibles themselves. The extrinsic muscles of each jaw include two dorsal muscles and two ventral muscles. The first dorsal muscle (fig. 55 B, 1) is a large conical bundle of fibers arising posteriorly on the cranium and inserted by a strong tendon on the base of the dorsal plate of the gnathal lobe (D, 1). This muscle is evidently the retractor of the mandible, but it must also somewhat flex the gnathal lobe on the mandibular base. The second dorsal muscle (B, 2) arises on the cranium and is inserted dorsally on the posterior end of the jaw. The ventral musculature includes two bundles of fibers. One is a long muscle (B, 3) arising anteriorly on the head apodeme (hAp) of the same side and inserted posteriorly on the concave inner side of the mandible; it is the principal protractor of the jaw. The other ventral muscle (4) arises medially on an intergnathal ligament (Lg) supported on the head apodemes, and its spreading fibers are inserted within the cavity of the mandible; the two corresponding muscles from the opposite jaws are the mandibular adductors. The intrinsic musculature of the mandible of Scutigera includes two muscles (D, 5) arising within the cavity of the jaw, the longer one attached ventrally on the base of the gnathal lobe, the shorter one dorsally. These two muscles evidently can serve only to flex the gnathal lobe on the base of the jaw.

The undersurface of the head will be now fully exposed with the removal of the feeding appendages. It is then seen that a long, epipharyngeal surface extends back from the labrum to the mouth (fig. 54 D, E, Ephy), though the mouth is normally concealed above the base of a large median lobe of the ventral head wall, known as the hypopharynx (E, Hphy). Most of the epipharyngeal area is membranous, but from weak lateral sclerotizations just behind the labrum two sclerotic rods converge posteriorly (D) to a crossbar, from which slender tapering arms continue to the mouth, where they appear to cross each other and end in the dorsal wall of the stomodaeum. Laterally two other bars (D, E, w) diverge posteriorly to the anterior angles of two large sternal plates of the ventral head wall (Flt). It is in the angles between these bars and the plates that the anterior articular processes of the mandibles are held.

The hypopharynx of Scutigera is a large, soft, elongate median lobe of the ventral head wall (fig. 54 E, Hphy), arising just in front of the bases of the first maxillae and projecting forward between the gnathal lobes of the mandibles well beyond the mouth, which latter is thus hidden in a ventral view of the head. The name “hypopharynx” given to this suboral lobe of the head is, of course, a misnomer, since the organ in question is entirely outside the mouth and has no anatomical relation to the pharynx. The term metastome would be more appropriate, but “hypopharynx” is current in myriapod and insect nomenclature. The size and shape of the hypopharynx will appear different in different specimens; in some the organ is swelled out into a large vesicle, in others it is variously contracted. The dorsal surface (fig. 54 F) is much longer than the ventral surface, since it extends posteriorly to the mouth (Mth); it is conspicuously marked by a pair of lateral rodlike thickenings, beginning anteriorly as S-shaped loops on the sides and converging posteriorly to be continued by parallel median extensions to the mouth. Here the two rods give off upcurved ribs into the lateral mouth walls and then run on into a pair of thicker bars in the floor of the stomodaeum (Stom).

At the sides of the hypopharynx (fig. 54 E) are the two ventral plates of the head wall above-mentioned. Each plate (Flt) expands laterally and is attached by its posterior lateral angle to the margin of the cranium; mesally it is extended forward as a tapering arm against the side of the hypopharynx, and posteriorly it gives off a large apodeme (hAp) into the head cavity. These plates are called by German writers the kommandibulares Gerüst, but since they are more intimately associated with the hypopharynx than with the mandibles, the writer (1951) has termed them hypopharyngeal fulturae (i.e., hypopharyngeal supports). Literally, however, the plates in question are premandibular sternal sclerites of the head; they are characteristic features of the Chilopoda, and are present in some Diplopoda, but no corresponding plates are known in the crustaceans or insects.

The apodemes of the fultural plates have been known as “hypopharyngeal apophyses”; Fahlander (1938) calls them “mandibular apodemes,” but inasmuch as they pertain to the sternal plates and not to the hypopharynx, or the mandibles, they may be better termed the ventral head apodemes of the chilopods, though, because of their premandibular origin, they clearly have no relation to the usual “head apodemes” of Crustacea that arise between the two maxillary segments. The inner ends of the apodemes in Scutigera support a broad sheet of soft tissue (fig. 54 E, Lg) that in a freshly dissected specimen appears to fray out on each side into the adductor muscle fibers of the mandibles and the two pairs of maxillae. When the muscles are removed, however, there is left a thin ligamentous plate of definite shape (G), supported from below on the posterior ends of the head apodemes (hAp) and from above by slender suspensory arms attached dorsally on the cranium; lateral and posterior arms give attachment to muscles. The structure is very similar to that described by Fahlander (1938, fig. 6 A) for Thereuonema. The apodemes are simply imbedded in the tissue of the ligament and are readily detached. The ligament has a partly fibrous structure and slowly dissolves in caustic, as do the ventral “endoskeletal” arms of the body segments. The ligament is quite comparable to the endosternum of Limulus and the arachnids, but it can have no relation to the central plate of the insect tentorium, which is a sclerotized chitinous tissue.

The legs of Scutigera (fig. 56 F), in spite of their great length, have each only seven true segments. The basal part of most of the legs is a large, complex structure on the side of the supporting body segment between the tergum and the sternum (A, B). The basal segment of the telopodite is a very small, ringlike first trochanter (A, 1Tr), which is followed by a large second trochanter, or prefemur (F, 2Tr). The two trochanters are but weakly attached to each other, so that the legs of Scutigera readily break off between these two segments. The second trochanter is followed by an elongate femur (Fm) and a still longer tibia (Tb). The extremely long, slender distal part of the leg with numerous short annulations is the tarsus (Tar); the leg ends with a small simple claw, which is the pretarsus (Ptar). The tarsus is divided by a joint beyond the middle into two principal subsegments, which are merely flexible on each other, there being no interconnecting muscles. Though no muscles are present within the tarsus, a slender tendon (G, t), attached on the ventral angle of the base of the pretarsal claw, traverses the tarsus and the tibia and gives attachment to the flexor muscles of the pretarsus in the proximal segments of the leg. The pretarsal musculature of the legs is thus seen to be the same as that of the maxillipeds (fig. 55 I). In none of the chilopods, or other myriapods, or in the insects does the pretarsus have an extensor, or levator, muscle. The extraordinary length of the hind legs of Scutigera (fig. 52) is due mostly to the extreme length of the slender, threadlike tarsi.

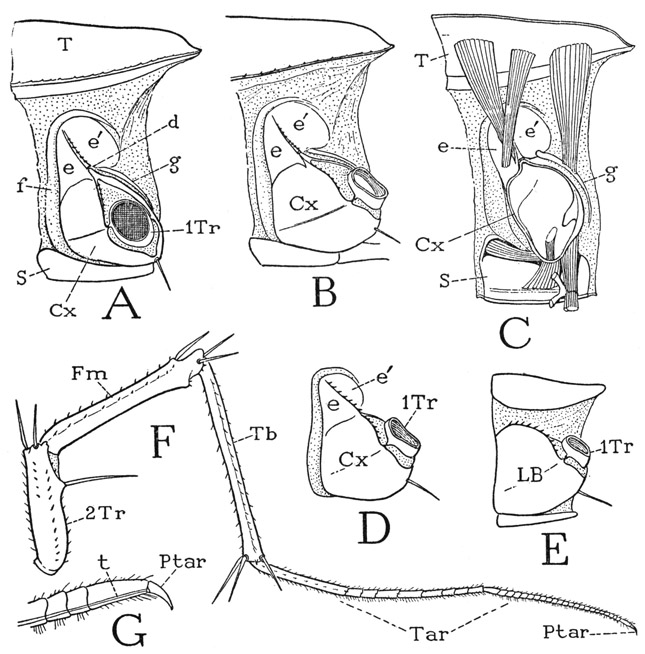

Fig. 56. Chilopoda—Scutigeromorpha. Scutigera coleoptrata (L.). The legs.

A, left side of segment from middle of body, showing leg base composed of coxa (Cx) and subcoxal sclerites (e, e’, f, g). B, left side of eleventh leg-bearing segment. C, mesal view of right half of a body segment, with basal muscles of leg. D, leg base of thirteenth leg-bearing segment, subcoxal sclerites united with coxa. E, leg base of last leg-bearing segment, subcoxal sclerites confluent with coxa. F, a left leg, except coxa and first trochanter. G, pretarsus and distal part of tarsus, showing flexor tendon (t) of pretarsus.

For explanation of lettering see pages 223–224.

The nature of the basal parts of the chilopod legs is difficult to understand. The typical structure is best developed on the middle segments of the body (fig. 56 A, B), and the principal element in the complex appears to be the coxa (Cx), since it supports the telopodite and retains the small first trochanter (A, 1Tr) when the leg breaks off. The coxa is articulated (d) to a plate above it divided into two parts (e, e’) by a spiny median ridge. Curving over this plate and running down the anterior side of the coxa is a long integumental fold (f), and from the posterior part of the plate a narrow sclerite (g) goes downward behind the coxa. These peripheral sclerites of the leg base have been interpreted as pleurites by Verhoeff (1906), who terms the supracoxal plate (e, e’) the “katopleure,” the fold above and before it (f) the “anopleure,” and the postcoxal strip (g) the “coxopleure.” In some of the other chilopods, however, there are distinct pleural sclerites between the leg bases and the terga (figs. 60 E, 61 B, pl). There is also the theory that the peripheral sclerites of the leg base represent a primitive “subcoxal segment” of the limb, an idea for which there is no convincing evidence, but the parts in question may be termed “subcoxal sclerites” merely to denote their position relative to the apparent coxa.

An examination of the basal musculature of the leg (fig. 56 C) shows that the anterior and posterior dorsal muscles are attached, respectively, on the “katopleure” and the “coxopleure,” which fact would suggest that these sclerites are differentiations of the coxa itself. Moreover, on the more posterior body segments the subcoxal elements become united with the coxa (D), and, finally, on the last leg-bearing segment (E) there is no distinction of coxal and subcoxal parts; the base of the leg is here an undivided plate (LB), which has all the appearance of a simple coxa implanted between the tergum and the sternum, and the dorsal muscles of the leg are attached on it. The nature of the “subcoxal” sclerites will be further discussed in connection with the other chilopods to be described.

LITHOBIUS

The genus Lithobius, of which there are many closely related species, is representative of the chilopod subclass Lithobiomorpha, the members of which are anamorphic in their postembryonic development as are the Scutigeromorpha, although structurally in some respects the two groups are quite different. In their general appearance the Lithobiomorpha more resemble the epimorphic Scolopendromorpha, particularly in that the head and body are flattened, the legs relatively short, the antennae placed at the anterior end of the head, and the spiracles situated along the sides of the body.

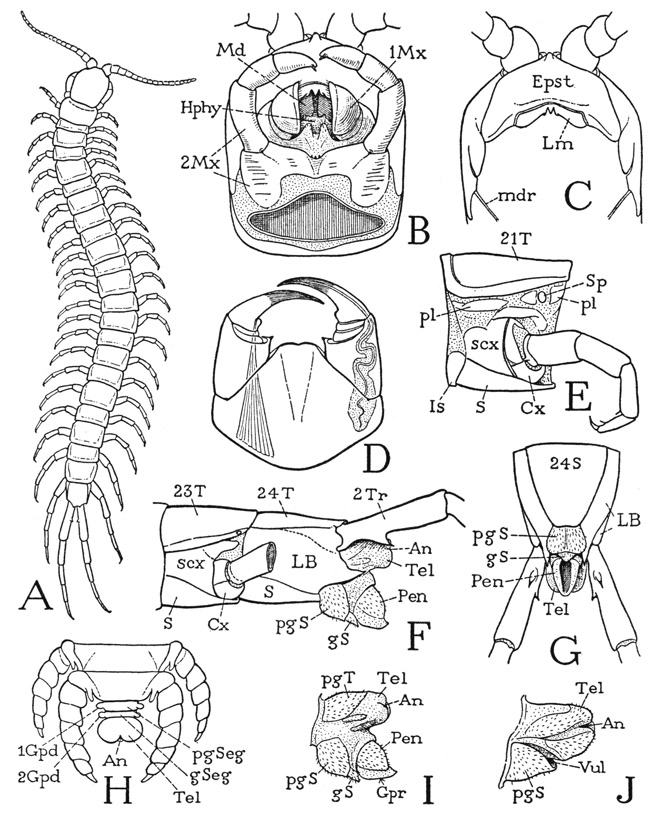

Fig. 57. Chilopoda—Lithobiomorpha. Lithobius sp.

Lithobius (fig. 57), in common with Scutigera, has 15 pairs of legs, but in Lithobius there is a tergal plate for each pair of legs, though the terga are not all of the same size. Immediately behind the head is a short tergum (fig. 59 A, 1T) of the maxilliped segment; the next is a long tergum (2T) belonging to the first pair of legs; then follows an alternation of short and long terga back to the eighth and ninth segments, in both of which the terga are long (fig. 57). With segment 10 the short and long succession begins again and continues to segment 15, but the tergum of segment 16 is also long, though shorter than the one preceding. On the undersurface of the body there is no sternal plate of the maxilliped segment (fig. 59 I), but there are 15 sterna of approximately equal size (fig. 58 F) for the 15 leg-bearing segments. Between the segmental sternal plates (S) are small, paired intersternites (Is) that do not represent segments. The spiracles lie in the membranous pleural areas of the segments above the leg bases and somewhat behind them (fig. 58 C, Sp). In the species of Lithobius here illustrated spiracles are present on segments 4, 6, 9, 11, 13, and 15, which are all segments having long terga. On segment 2 is a small papilla in the spiracle position, but it has no opening, though in some species there is a functional spiracle on this segment. The last spiracle, on segment 15, is very small. Species of Lithobius differ in the number of spiracles, those on segments 4 and 11 being said to be the only ones that are never absent. As in Scutigera, there are in Lithobius no pleural sclerites above the leg bases.

Following the last leg-bearing segment is a small pregenital segment. In the male this segment has a well-developed tergal plate, but normally it is entirely concealed by retraction beneath the preceding tergum; on the undersurface, however, the sternum is fully exposed (fig. 58 G, 17S) and bears on its posterior margin a pair of vestigial gonopods (Gpd). Between the gonopods projects the tip of a large intromittent organ (Pen), or penis (I), which is ordinarily retracted above the sternum. The body ends with a simple, anusbearing telson (G, Tel). In the female the tergum of segment 17 is reduced to lateral sclerotizations of the dorsum (J, 17T), but the sternum is well developed (H, J, 17S) and bears a pair of three-segmented gonopods (Gpd), one of which is shown separately at E. Between the bases of the gonopods and behind the supporting sternum is the female genital opening.

The legs of Lithobius (figs. 57, 58 A) are much shorter than those of Scutigera, owing principally to the great length of the tarsi in Scutigera, but they have the same segmentation (fig. 58 C), and the tarsi are each divided into two subsegments (B, C, Tar). As in Scutigera, the legs of Lithobius break off between the two trochanters. The simple, clawlike pretarsus (Ptar) is provided with a long, slender tendon (B, t) attached ventrally on its base, which gives insertion to large flexor muscles (flptar) arising in the tibia and the femur. The leg base of Lithobius (C) has the same structure as in Scutigera, except that the peripheral subcoxal sclerites (scx) are somewhat less developed and the anterior sclerite is continued ventrally between the sternum and the coxa (C, F). The coxa has an articular point (C, i) on the ventral subcoxal arc, as well as a dorsal articulation on the sclerite above it. On the last leg-bearing segment, however, as also in Scutigera, the long hind leg is supported on a simple basal plate (J, LB), in which the subcoxal sclerites of the preceding segments appear to be incorporated. The same condition will be again encountered in the Scolopendromorpha and the Geophilomorpha. It is a question, therefore, whether the subcoxal sclerites of the chilopods are pleural elements that have been united with the coxae on the posterior segments, or whether they are coxal derivatives that have become detached from the coxae on the more anterior segments. At present there is no satisfactory answer to the question.

Fig. 58. Chilopoda—Lithobiomorpha. Lithobius sp. The body segments and the legs.

A, cross section of body segment with legs attached. B, segmentation of leg beyond second trochanter. C, left side of a body segment with leg, showing subcoxal sclerites around base of coxa. D, base of last leg, left side, with simple coxa. E, gonopod of female. F, undersurface of three consecutive body segments, part of third sternum cut off to show a subcoxal fold beneath coxa. G, terminal body segments of male, ventral. H, same segments of female, ventral. I, penis and ducts, ventral. J, terminal body segments of female, lateral.

For explanation of lettering see pages 223–224.

It is in the structure of the head that the Lithobiomorpha differ conspicuously from the Scutigeromorpha. The head of Lithobius is flattened (figs. 57; 59 A), the eyes have a forward position on the sides of the head, and the relatively short, thick antennae arise directly from the anterior end of the head. To accommodate this position of the antennae, the epistomal region and the labrum have been inflected upon the undersurface of the head in Lithobius (fig. 59 B), where together they conceal the epipharyngeal surface, and the broad labrum (Lm) underlaps the anterior ends of the mandibles (Md). The undersurface of the lithobiid head, therefore, resembles the undersurface of the head of a decapod crustacean (fig. 42 A), but the modification must be secondary in each case, since the head structure of Scutigera undoubtedly is more primitive than that of Lithobius. Whatever its position, the epistome is still to be regarded as the anterior part of the true dorsal surface of the head. The labrum of Lithobius is entirely separated from the epistomal margin.

The antennae of Lithobius are much shorter and relatively thicker than those of Scutigera, and are divided into many small sections, but all of the sections have been shown by Imms (1939) to be true antennal segments, since each one is individually provided with muscles arising in the segment proximal to it. In the species here described there are about 20 segments in each antenna, but in other species the number may be smaller or much greater.

Inasmuch as the mouth parts of the centipede underlap each other from behind forward, they may be more conveniently studied in reverse order, beginning with the poison claws, which, though they are the appendages of the first body segment, are a part of the feeding apparatus.

The poison claws, or maxillipeds, of Lithobius (fig. 59 I, Mxpd) lie horizontally against the underside of the head, with the fangs turned mesally. The large, flat coxae (Cx) are weakly joined in a long median suture, forming a broad plate with a toothed margin covering the maxillae from below. The telopodites have each only four distinct segments, but it is to be observed that the tendon of the flexor muscle of the claw is attached, not on the base of the claw, but to the inner side well within the base, which fact is good evidence that the claw, or poison fang of Lithohius, consists of the pretarsus (Ptar) united with the tarsus (Tar). It is only in the Scutigeromorpha among the chilopods that the pretarsus is separated from the tarsus. The two pairs of maxillae (fig. 59 G) arise close together from wide bases in front of the maxillipeds and extend forward against the undersurface of the head. The coxae of the second maxillae (G, Cx) are broadly united with each other behind the bases of the first maxillae; the palpuslike telopodites consist each of four segments, including a terminal claw, and reach forward beneath the epistome and the bases of the antennae. The first maxillae (H) are relatively simple appendages, each having a large basal segment produced mesally in a triangular endite and supporting laterally a short, two-segmented telopodite. The bases are closely approximated but are not united, and the two appendages together form a triangular underlip that projects forward beneath the mandibles and the labrum.

Fig. 59. Chilopoda—Lithobiomorpha. Lithobius sp. The head and the mouth parts.

A, head and first five body segments, dorsal. B, head, ventral, mandibles in place, but both pairs of maxillae removed, exposing mandibular pouches (mdP). C, left mandible, laterodorsal. D, circumoral region of ventral wall of head, showing hypopharynx, fultural sclerites, and the head apodemes. E, right mandible and its muscles, dorsal. F, posterior end of mandible with articular rod. G, first and second maxillae, and rear end of head, ventral. H, first maxillae, ventral. I, maxillipeds and first leg-bearing segment, ventral.

For explanation of lettering see pages 223–224.

The mandibles of Lithobius (fig. 59 B, Md) are in general form similar to those of Scutigera, but their long, tapering, incurved posterior ends are contained in pockets (mdP) of the membranous ventral wall of the head, inflected at the sides of the first maxillae and extended posteriorly above the bases of the second maxillae (G, mdP). An articular rod (B, mdr) connects the end of each mandible with a marginal plate of the cranium (m). Anteriorly an articular process on the dorsal side of the mandible (E, c) catches loosely in the angle between the corresponding fultural sclerite (D, Flt) and its epipharyngeal branch (w). The entire mandible is weak and flexible, and a break in the sclerotization at the base of the gnathal lobe (C, E) would appear to make the latter flexible on the basal part of the jaw.

The mandibular musculature of Lithobius (fig. 59 E) is essentially the same as that of Scutigera. A large dorsal muscle of the gnathal lobe (1) arises with widely spreading fibers on the cranial wall and is evidently a flexor of the lobe as well as a retractor of the mandible as a whole. A second smaller dorsal muscle (2) is attached proximally on the base of the jaw. A long protractor (3) goes from the base of the head apodeme (hAp) to the posterior end of the mandible. The adductor fibers corresponding with muscle 4 of Scutigera (fig. 55 B) are differentiated into two groups in Lithobins (fig. 59 E), a distal group (4a) attached on the head apodeme and a proximal group (4b) attached on the interapodemal ligament (Lg). Finally, there is an intramandibular flexor of the gnathal lobe (5).

On removal of the mandibles the circumoral region of the ventral head wall will be exposed (fig. 59 D). Medially is the hypopharynx (Hphy), which projects forward below the mouth (Mth), and on each side of it is a long, transverse premandibular fultural sclerite (Flt) attached laterally to the marginal plate of the cranium (B, m). Anteriorly each fultura gives off a short branch (D, w) into the membranous epipharyngeal wall (Ephy), its mesal end is produced into a recurved arm imbedded in the lateral wall of the hypopharynx, and from its posterior margin a long, tapering apodemal process (hAp) extends posteriorly into the head cavity. The two apodemes are connected by a broad transverse ligament (Lg) below the pharynx. The relation of the mandibular muscles to the head apodemes and their connecting ligament was noted in the last paragraph.

OTOCRYPTOPS

The Scolopendromorpha, of which Otocryptops is an example, are similar in their general appearance to the Lithobiomorpha but are to be distinguished superficially from the latter by their greater number of legs, some having 21 pairs and others 23 pairs. Correspondingly, they have 25 or 29 body segments, including the maxilliped segment, two segments in the genital region, and the telson. The typical genus of the order, Scolopendra, has 21 pairs of legs; Otocryptops, described here (fig. 60 A), is one having 23 pairs.

Otocryptops sexspinosa (fig. 60 A) is a common centipede associated with Lithobius in the eastern part of the United States. The back plates of the body are more uniform in size than are those of Lithobius, but they show a tendency to alternation of longer and shorter plates, especially on the anterior segments. The large first tergum possibly includes the tergum of the maxilliped segment, since this segment has no separate tergal plate of its own. On the undersurface of the body most of the segmental sterna (fig. 60 E, S) are separated by narrow intersternites (Is). The legs, except the last two pairs, are seven-segmented, and associated anteriorly and dorsally with the narrow coxa (Cx) is a large subcoxal sclerotization (scx). Between the latter and the tergum are several small sclerites (pl) that may be regarded as pleurites (pl), though some writers term them paratergites. Spiracles, associated with the pleurites, are present on segments 4, 6, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, and 23. As in the other chilopods, the coxal and subcoxal sclerotizations appear to be confluent on the last leg-bearing segment (F), in which the leg is supported on a large lateral plate (LB) completely occupying the space between the tergum and the sternum. By comparison with the preceding segment (23) it would appear that the principal part of this plate on segment 24 is derived from the subcoxal element.

The legs of the next to the last pair (on body segment 23, fig. 60 F) differ from the others in having eight segments instead of seven, including the coxa (Cx) and a small first trochanter united with the long second trochanter. The legs of the last pair (A) have the same structure, except that there is no first trochanter (F). The unusual segmentation of these two appendages may be supposed to be explained on the assumption that the last two apparent segments before the pretarsus are subdivisions of the tarsus, since the tarsus is thus divided in the embryo of all the legs of Scolopendra (fig. 60 H), as it is in Scutigera and Lithobius (figs. 56 F, 58 B). An examination of the musculature of either of the last two legs of Otocryptops, however, shows that while no muscles have their origins in the penultimate segment, the antepenultimate segment not only gives origin to a long series of fibers attached on the tendon of the pretarsal claw but contains also a levator and depressor muscle of the penultimate segment. This same type of segmentation and musculature is seen also in the last leg of a geophilid (fig. 61 G). Attems (1926c) suggests that the simplest way to explain this apparent anomalous condition is to assume that some of the pretarsal muscles have shifted their origins back to the proximal subsegment of the tarsus. The explanation, however, is too simple; such a transposition of the pretarsal muscles is not known in any of the other myriapods or in the insects. The musculature of a leg of Scolopendra (fig. 61 H), which does have two tarsal subsegments, shows that the last group of pretarsal fibers still takes its origin in the tibia (Tb) just as in any seven-segmented leg (F). It is evident, therefore, that in the eight-segmented leg of Otocryptops or the geophilid (G) the antepenultimate segment is the tibia (Tb); the presence of levator and depressor muscles attached on the base of the penultimate segment, moreover, is confirmatory evidence that this segment alone is the tarsus (Tar). Finally, it is to be noted that the distribution of the pretarsal muscles is the same in all the legs (fig. 61 F, G, H) regardless of the number of segments or the division of the tarsus. The extra segment of the eight-segmented leg of Otocryptops, therefore, must be in the trochanteral region. The free six-segmented telopodite of the last leg clearly lacks the first trochanter (fig. 60 F), but otherwise the segmentation of this leg corresponds with that of the eight-segmented leg preceding.

Fig. 60. Chilopoda—Scolopendromorpha. Otocryptops sexspinosa (Say), except H.

A, entire centipede. B, head and mouth parts, ventral. C, anterior part of head, ventral, mouth parts removed. D, maxillipeds (poison claws), ventral. E, middle segment of body and leg, left side, showing pleural sclerites (pl) above subcoxal sclerites of leg base. F, terminal body segments of male, left side. G, same, ventral. H, terminal part of body of embryo of Scolopendra, dorsal (from Heymons, 1901). I, genitoanal region of male, left side. J, same of female.

For explanation of lettering see pages 223–224.

The genital and anal region of Otocryptops projects beyond the twenty-fourth segment beneath the bases of the hind legs (fig. 60 F). In the male the pregenital segment has a distinct tergum and sternum (I, pgT, pgS), and beyond the latter there projects a small genital sternum (gS), from above which is protruded a large intromittent organ (Pen), open on the ventral surface (G). The structure is simpler in the female (J): the genital passage here opens (Vul) above the single sternum (pgS), which evidently is that of the pregenital segment. As already noted, there are in the embryo of Scolopendra (H), according to Heymons (1901), two small but distinct segments in the genital region between the segment of the last legs and the telson. The telson of the adult is a short simple lobe in each sex (F, I, J, Tel).

The head and mouth parts of Otocryptops are not essentially different from those of Lithohius. The Cryptopidae have no eyes, though eyes are present in Scolopendridae. On the underside of the head the epistome (fig. 60 C, Epst) covers a large area behind the bases of the antennae and carries the narrow labrum (Lm) on its posterior margin. The rest of the ventral surface of the head (B) is occupied by the mandibles (Md), the hypopharynx (Hphy), and the two pairs of maxillae (1Mx, 2Mx). Below these parts lie the maxillipeds (D), the coxae of which are completely united ventrally in a large basal plate supporting the movable, four-segmented telopodites; the free distal margin of the coxal plate presents a pair of slightly rounded, sharp-edged lobes, but it is not toothed or spined. The claws are articulated laterally on the large basal segments of the maxilliped telopodites, the two intervening segments in each appendage being very small and incomplete laterally. The long poison gland of each claw extends into the base of the coxa. The claw itself is seen to be composed of the united tarsus and pretarsus, since, as in Lithobius, the tendon of the flexor muscle is attached well within its base.

The second maxillae (fig. 60 B, 2Mx) will be fully exposed on removal of the maxillipeds. The large coxal segments are connected by a median bridge, the telopodites are four-segmented, including a small, somewhat subapical claw on the end of the third segment. The first maxillae (1Mx) likewise have a common base, from which two soft, setigerous, median endites project forward between the bases of the thick, ventrally extended, two-segmented telopodites. The apical segments of the latter have broad, concave mesal surfaces and are ordinarily closed against each other like a pair of valves beneath the mandibles, but when the animal is experimentally stimulated in the mouth region, they move apart and the palpuslike telopodites of the second maxillae are then convulsively and repeatedly thrust between them. The movement is evidently a feeding reflex and suggests that the space between the first maxillary lobes is the outer entrance to the mouth, and that the food is pushed into it to the mandibles by the second maxillary palpi. No movement of the mandibles was observed.

The mandibles of Otocryptops are similar in form and structure to those of Lithobius, except that they are abruptly angulated instead of curved. The gnathal lobes close against the hypopharynx between them and lie against a pair of premandibular sternal plates of the head wall above them, which plates support the hypopharynx medially and give off posteriorly into the head cavity a pair of apodemes. Each mandible has a loose anterior articulation with the corresponding fultural plate, and posteriorly it is connected with the cranial margin by a delicate rod (fig. 60 C, mdr) in the membrane that suspends the mandible from the head. The mandibular musculature is the same as that of Lithobius.

A GEOPHILID

The geophilomorph chilopods are those slender centipedes with numerous body segments and short legs (fig. 61 A). In the number of segments and in details of general structure the Geophilomorpha are much less standardized than are the members of the other orders. The number of body segments in different species is said to vary from 35 to 181 and is not constant even within a single species. Corresponding to each pair of legs are a main tergal and a sternal plate, but these plates are separated by narrower intertergites and intersternites throughout the length of the body. The order is divided into ten families, but since space cannot be devoted here to a description of the characters of the various forms, the following brief account is based on a species of the family Geophilidae, from which the order gets its name.

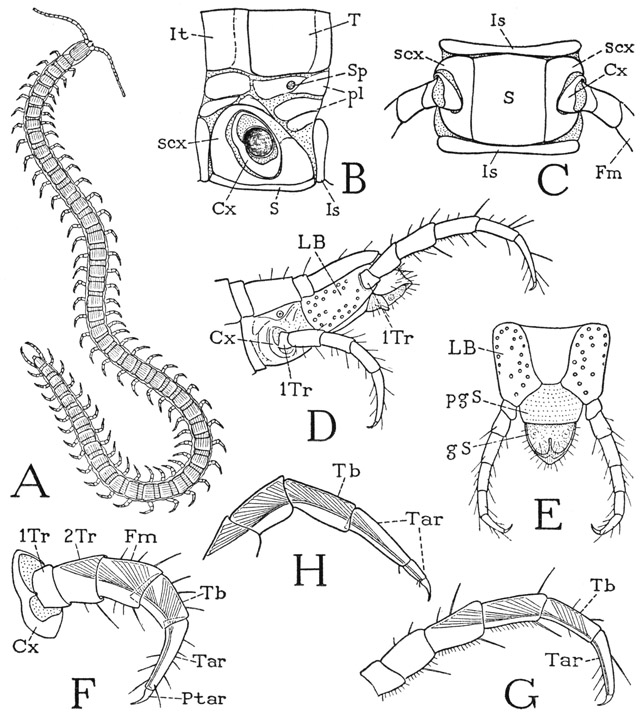

Fig. 61. Chilopoda—Geophilomorpha.

A, a geophilid, unidentified species. B, Strigamia bothriopus Wood, a middle segment of body and leg base, left side. C, same, ventral surface of a body segment. D, same species as A, posterior part of body and legs. E, same, end of body and last legs, ventral. F, same, typical leg segmentation. G, same, last leg, except coxa. H, Scolopendra sp., distal part of last leg, showing subdivision of tarsus, and pretarsal muscle.

For explanation of lettering see pages 223–224.

A typical geophilid is shown at A of figure 61. The specimen is 40 mm. long and has 50 body segments between the head and the genital region. The first dorsal plate behind the head (fig. 62 A, E, 1) is the tergum of the maxilliped segment; the following terga belong to the 49 leg-bearing segments. The first of these (2) is a single plate, but the others are accompanied by intervening intertergites (fig. 61 B, It), which belong to the anterior parts of their respective segments; the last intertergite lies before the main tergal plate of the last leg-bearing segment (D). On the undersurface of the body (C) the main sternal plates (S) lie between the large leg bases and are separated by narrow interstemites (Is), which are more strictly intersegmental than are the intertergites.

The legs, except those of the last pair, are all alike, and each has the usual seven segments (fig. 61 F). The coxa (Cx) is a small ring at the base of the limb (B, C) and is almost surrounded by a large subcoxal sclerotization (scx), which is continuous ventrally (C) in a wide arc between the coxa and the sternum. The peripheral sclerotization of the leg base in the geophilid thus gives the best example among the arthropods of what might be regarded as a subcoxal segment of the leg, but it seems hardly probable that a primitive basal limb segment should be retained best developed in an otherwise highly specialized order. Intervening between the tergum and the subcoxal ring of the leg base on the side of the body segment (B) are a number of small sclerites, or thickened areas of the integument (pl), which may be regarded as true pleurites, or laterotergites. A spiracle (Sp) is present in this region on each legbearing segment but the first and the last.

On the last leg-bearing segment (fig. 61 D) the coxal and subcoxal areas of the limb base appear to be blended in a single large plate (LB) occupying the entire space between the tergum and the sternum. In the geophilids this plate is characteristically dotted with the dark-rimmed orifices of dermal glands. The free part of the terminal legs is somewhat longer than that of the other legs and has seven segments instead of six, and yet the small basal segment appears to be the first trochanter (1Tr) by comparison with the preceding legs. As already pointed out in the discussion of the similarly eight-segmented legs of Otocryptops, the extra segment is not a subdivision of the tarsus, because the antepenultimate segment (G, Tb) contains a branch of the flexor muscle of the pretarsus and clearly corresponds with the tibia of the preceding legs (F, Tb). The tarsus of the last leg (G, Tar), furthermore, is identical with the tarsus of the other geophilid legs (F, Tar), and there is no suggestion of a tarsal subdivision such as that present in the legs of Scolopendra (H). The eight-segmented leg, therefore, must have an extra segment interpolated in its proximal part, if the supporting plate (LB) includes the coxa as it appears to do.

Fig. 62. Chilopoda—Geophilomorpha. Unidentified species shown at A of figure 61.

A, head and anterior part of body, lateral. B, same, ventral. C, first and second maxillae, ventral. D, head, ventral, mouth parts removed. E, head and anterior part of body, dorsal.

For explanation of lettering see pages 223–224.

The relatively small, slender head of the geophilid (fig. 62 A, H) rests on the large maxillipeds (Mxpd). Eyes are absent, and the antennae, each of 14 distinct segments, arise from the anterior end of the cranium, as in Lithobius and Otocryptops. On the undersurface of the head (D), behind the antennal bases, is a large epistomal region (Epst), which bears on its posterior margin the narrow labrum (Lm). The geophilid labrum (Lm) differs from the labrum of the other orders in that it lacks a median tooth and is divided into a short median part, armed with a row of teeth, and two longer lateral parts. Premandibular sclerites of the ventral head wall (Flt) are present as in the other chilopods; their lateral arms are attached to the cranial margins but are mostly concealed by the underlapping edges of the epistome, their mesal arms clasp the sides of the hypopharynx (Hphy), and each sclerite gives off a short apodeme (hAp) extending posteriorly into the head. The head apodemes of the geophilomorphs, however, have no connecting ligament.

The true ventral surface of the head is almost entirely covered by the huge maxillipeds (fig. 62 B), the coxae of which are completely united in a large shield-shaped plate (Cx). The telopodites are four-segmented, and the points of the fangs project beyond the basal segments of the antennae. In each appendage the fang is articulated directly on the basal segment of the telopodite, the small second and third segments being incomplete laterally; the insertion of the long flexor muscle within the base of the fang shows that the latter is a composite segment formed by the union of the tarsus with the pretarsus, as in Lithobius and Otocryptops. The two maxillary appendages (fig. 62 C) are closely associated; in each pair the coxae are entirely united in a wide basal plate. The mandibles of the Geophilomorpha are highly variable in form; some of them resemble the mandibles of other chilopods, but in the geophilid here described each mandible has a wide, triangular anterior expansion and a narrow curved posterior extension. The adductor muscles are all attached directly on the head apodemes.

Explanation of Lettering on Figures 53–62

a, posterior articulation of mandible.

af, antennifer.

An, anus.

Ant, antenna.

Atr, atrium of spiracle.

c, anterior, epipharyngeal articulation of mandible.

Cx, coxa.

cxnd, coxal endite.

d, articulation between coxa and subcoxal sclerites.

Dct, duct.

e, e’, dorsal subcoxal sclerites, “katopleure.”

E, eye.

Epst, epistome.

f, precoxal fold, “anopleure.”

flptar, flexor muscle of pretarsus.

Flt, fultura of hypopharynx, premandibular sternal sclerite of head.

fltar, flexor muscle of tarsus.

Fm, femur.

g, postcoxal sclerite, “coxopleure.”

Gld, gland.

gnL, gnathal lobe of mandible.

Gpd, gonopod; 1Gpd, 2Gpd, first and second gonopods.

Gpr, gonopore.

gS, sternum of genital segment.

gSeg, genital segment.

H, head.

hAp, head apodeme.

Hphy, hypopharynx.

i, ventral articulation of coxa.

Is, interstemite.

It, intertergite.

L, leg.

LB, limb base, union of coxa and subcoxal sclerites.

Lg, intergnathal ligament of head apodemes.

Lm, labrum.

m, marginal sclerite of cranium.

mb, membrane.

Md, mandible.

mdB, base of mandible.

mdP, mandibular pouch.

mdr, articular rod of mandible.

Mth, mouth.

1Mx, first maxilla.

2Mx, second maxilla.

Mxpd, maxilliped, poison claw, first leg.

Pen, penis.

pgS, sternum of pregenital segment.

pgSeg, pregenital segment.

pgT, tergum of pregenital segment.

pl, pleurites.

Ptar, pretarsus, dactylopodite.

S, sternum.

scx, subcoxal sclerites.

Seg, body segment.

Sp, spiracle.

Stom, stomodaeum.

t, tendon.

T, tergum.

Tar, tarsus.

Tb, tibia.

Tel, telson.

Tlpd, telopodite, part of leg beyond coxa.

Tr, trochanter; 1Tr, first trochanter, 2Tr, second trochanter or prefemur.

Vul, vulva.

w, epipharyngeal arm of fultural sclerite of hypopharynx.