Fac-simile letter from Zola to Vizetelly.

At the lunch at the Chalet des Iles the novelist's health was proposed by his old friend and publisher, M. Charpentier, and after the toast had been acknowledged, M. Catulle Mendès, who, as will be remembered, had gallantly assisted Zola when the columns of "La Cloche" and "Le Bien Public" were closed to "La Curée" and "L'Assommoir," spoke of the old quarrels between the Naturalists and the Parnassians, to which latter sect he, Mendès, had belonged. And, said he, though he still looked upon poetry as a much superior art to prose, he was anxious to declare publicly that he regarded Zola as one of the great literary glories of France. This was very pretty; and the novelist, not to be left behind in a matter of compliments, responded by referring to Mendès as a perfect artist and a good friend. Finally he proposed a toast to work, his old hobby, as he called it, the only one in which true happiness could be found. For some inscrutable reason General Iung—whose researches into the Iron Mask mystery may be remembered, and who happened to be among the guests on this occasion—thought the moment appropriate to re-echo a remark which had run through the newspapers, and to which one has already referred. "Monsieur Zola," said he, "you have written 'The Smash-up' ('La Débâcle'), let us hope that you will soon write 'Victory.'" "Ah, general!" replied Zola, raising his forefinger, "that is your business." And thereupon he sat down.

The value of books is not to be estimated by their length or even by their popularity. Yet it may not be inappropriate to point out that the Rougon-Macquart series, which Zola had now completed, was really a colossal performance. Besides a large variety of other work, the novelist had written the twenty volumes of that series in about five and twenty years, introducing, as he proceeded, no fewer than twelve hundred characters to his readers. The twenty volumes represented nine thousand pages of print, each of three and thirty lines, and, assuming an average of nine words per line and making allowance for "blanks,"—by no means numerous in Zola's works,—one may say that they contained quite two million five hundred thousand words. Passing to another matter, one finds that at the time of the appearance of "Le Docteur Pascal" there had been sold over half a million copies of the ordinary Charpentier edition of the series. The popular illustrated editions of several of the stories, first sold in what one may call "penny parts," had also circulated very widely, at least to the extent of a quarter of a million copies; and further there had been some éditions de luxe, copies on special papers, and so forth. Moreover, there were five novels written before the Rougon-Macquart series was begun, with four volumes of short stories and seven volumes of essays and other papers, issued at various times, and one may therefore assume that between eight and nine hundred thousand copies of Zola's books had been sold at the period we now deal with. And of course thousands and thousands of readers had been reached by serial publication. Of the circulation of the many translations it is impossible to give even an idea, but some of the English and American volumes had sold by tens of thousands, and there were versions of many of Zola's writings in German, Italian, Russian, Dutch, Hungarian, and other languages. But books, as we know, by no means represented the whole of Zola's work; there were also many scores, if not hundreds, of ephemeral uncollected newspaper articles to be added to them, as well as several plays, so that his output stood at quite five million words. It was evident then that he practised what he preached,—that gospel of work, which others, such as Tolstoï, the prophet of resignation, occasionally derided but which he himself found all-sustaining.

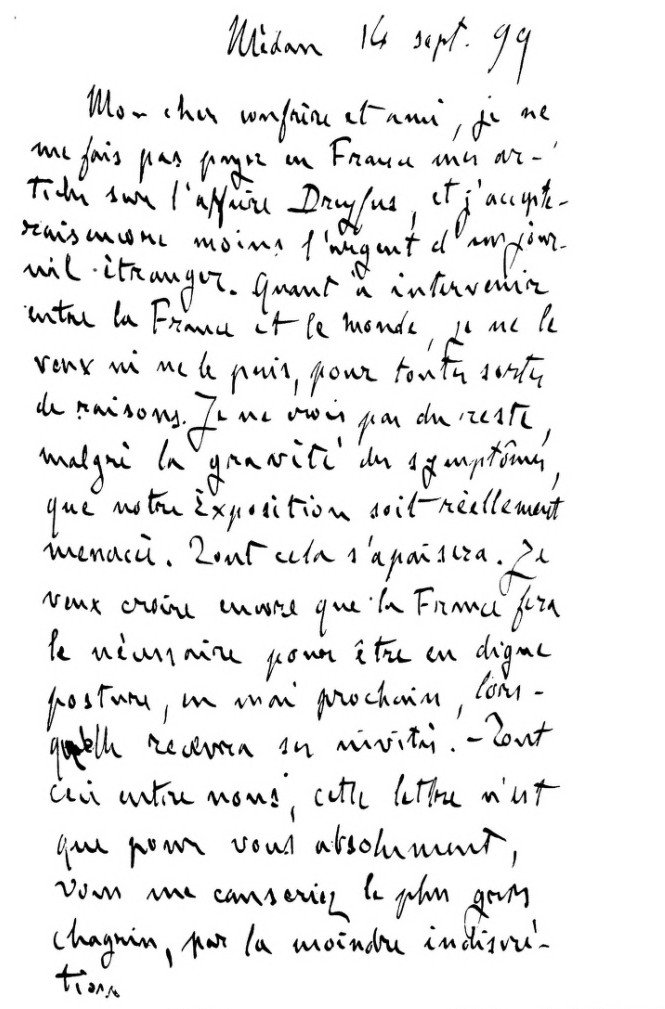

He took it as a part of his text when speaking at a gathering of the Paris Students' Association, over which he presided that year, 1893,[22] for though the Academy still refused him admittance, some recognition of his labours was coming from other quarters. On the occasion of the National Fête, following the completion of his great series, he was raised from the rank of chevalier to that of officer of the Legion of Honour; and for some years in succession, a very rare occurrence, he was chosen as Président de la Société des Gens de Lettres. It was this circumstance that caused the English Institute of Journalists to invite him and other representative French writers to attend one of its congresses in London. Zola's connection with Ernest Vizetelly had now become a close one. A translation of "Le Docteur Pascal" had followed that of "La Débâcle," and arrangements had been made for an English version of a previous work, "L'Argent," Zola indorsing all Vizetelly's proposals in a letter in which he said: "My dear confrère, I leave translation matters entirely to you, and it is sufficient you should tell me that an arrangement is good for me to accept it. I know you to be devoted to my interests, and you are well placed to decide everything."[23] Under these circumstances, early in August 1893, soon after receiving the invitation of the Institute of Journalists, Zola communicated with Vizetelly and asked him for certain information. "I should like to know," he wrote, "what will be the importance of this congress, and whether it will offer much interest. You know my position in London; my work is still very much questioned there, almost denied. It certainly seems to me that my presence, and the words I might speak, might efface much of the misunderstanding, and that it would be politic to accept, in order to influence opinion. But what is your view? Reply to me at once at Médan."

Vizetelly, in his reply, reviewed the situation such as it had become since the "The Downfall" which had conduced to a movement in Zola's favour. The English critics, he said, still made all sorts of reserves, asserting, for instance, that a new Zola had come into being and one of them even claiming that there were three Zolas, the author of "La Terre," the author of "Le Rêve," and the author of "La Débâcle"; for they were still so far from the truth, so unable to grasp the significance of the Rougon-Macquart series as a whole, that they could only explain the latter works by picturing some wonderful change in the novelist. Had they looked into the matter more closely they would have found "Le Rêve," with all its mysticism and poetry, followed by one of Zola's most naturalist volumes, "La Bête Humaine," which alone, by reason of its place in the series, demonstrated the fallacy of their assumption. But as Vizetelly pointed out, they, and English people generally, had to be taken as they were. The position had certainly improved, and Zola's presence in London might well make it better still, for in conversation as well as in his speeches he might be able to clear up many misunderstandings. At the same time it was proper to bear in mind that the Institute of Journalists had members in all parts of the country, and Vizetelly did not know how far the provincial districts might share the views of the London district, whence the invitation had emanated. Personally he was very much in favour of Zola accepting it, but he would make some inquiries before anything further was done. Zola himself thought that course advisable, for he at once replied: "If I did not immediately answer the invitation it was precisely because I felt somewhat distrustful, though it is difficult to believe that they have invited me with the intention of receiving me badly. I do not wish the English press to promise it will sing my praises, but I should like to be quite certain it will be polite while I am its guest. Please make the inquiries you propose, and tell me frankly what you think of the situation." And he added in a postscript: "I forgot to tell you that the invitation is addressed to M. Émile Zola, Président de la Société des Gens de Lettres."

That postscript was all important, for it explained the character of the invitation. Various amenities had passed between the French Society and the Institute of Journalists already, and now the Institute, being about to hold a conference in London, had courteously invited the officials of various foreign organisations. It so happened that Zola was one of the officials in question. If some other man had held his position in the Société des Gens de Lettres in 1893 that other man would certainly have been invited, and Zola in all likelihood would not have been asked at all. But the circumstances were not fully understood at the time, and some badly informed controversialists, in their anger at finding the hateful Zola a guest of an English newspaper organisation, subsequently heaped undeserved abuse on the Institute of Journalists. Vizetelly, however, made various inquiries of the Institute's officials, and having satisfied himself that Zola would have no reason to complain of his reception, he again wrote suggesting that the invitation should be accepted. On August 18 Zola, who meantime had also consulted M. George Petilleau, the official delegate of the Société des Gens de Lettres in England,[24] responded:

"I have just accepted, officially, the invitation of the English journalists, so it is quite decided that I shall attend their congress. It would be very kind of you to keep me informed of any incidents that may arise, and I also rely on you to let me know as soon as possible what toast I shall have to acknowledge [at the Institute's dinner]. I understand also that I shall be asked to speak on the question of anonymity in journalism. That is a big question in England, is it not? It would be very kind of you to tell me what you think of it, and what the majority of English journalists think. I want to know the ground beforehand."

Then on August 22 he wrote:

My dear Confrère,—I am preparing the few pages I wish to read on anonymity in English journalism, and I should like to have what information you can give me. I forgot to insist on one point: Is literary and artistic criticism anonymous, like other things, in England? Do your critics, I mean those who judge books and works of art, also refrain from signing their articles? Give me a little information on that point. Tell me clearly what is the position of criticism on your side (chez vous), if it numbers any remarkable men, if they are known, and if people become impassioned for or against them as in France. Again thanks, and very cordially yours, É. Z.

Vizetelly replied by sending him a memorandum, running to perhaps a thousand words, and Zola was further primed with information by others, some London correspondents of the French press, and also M. Petilleau, who took a prominent part in the proceedings. Writing again to Vizetelly on August 27, Zola said: "A thousand thanks for your excellent notes, they will enable me to write something interesting." In the same letter he gave some information respecting "Lourdes" which he was then preparing, and he again referred to that work in a note dated August 30, when he said: "I shall try every effort to make it one-fifth shorter than 'La Débâcle,' for such long novels are disastrous in France." Those efforts, however, were hardly successful, for when "Lourdes" was finished it proved to be only forty pages shorter than the novel on the war.

Though Vizetelly now had plenty of work before him—for besides completing the edition of "The Heptameron" on which he had been engaged in 1889, he was helping his father with his reminiscences,—he was anxious to make early arrangements with respect to "Lourdes" in the hope of profiting by any reaction in Zola's favour which the forthcoming visit to London might promote. In that respect, while he observed with pleasure that English newspaper men seemed to be recovering from their former aberration, he thought it hardly right to leave Zola entirely in the hands of a profession, many of whose members, only a few years previously, had covered him with unmitigated abuse. In these circumstances he communicated with Mr. afterwards Sir Walter Besant, whom he knew to be well informed respecting Zola and his works,[25] and who had also shown great personal kindness at the time of the Vizetelly prosecution. Besant took the hint immediately, but was almost at a loss what to suggest, for in all probability in the latter part of September, when Zola would arrive in London, few English authors of note would be there. However, he saw Mr. Oswald Crawfurd, chairman of the Authors' Club, and Mr. Crawfurd, a man of broad views like Besant himself, took up the matter with alacrity. During the interval which ensued, Mr. Besant wrote several times to Ernest Vizetelly, going so far, on one occasion, as to say, "A dinner will be given at the club to M. Zola and yourself on any day to be named—as quickly as possible—by yourself." But Vizetelly, while accepting the invitation on Zola's behalf, and also quite willing to attend the dinner, felt that he must not attempt to take any prominent part in the proceedings. If he had foreseen that his father, who was still living in retirement near Tilford, would be dead some three months later, he might have adopted quite another course, in order to procure some personal satisfaction for the poor old man who had been pelted with mud, ruined, and sent to prison. But he thought it premature to bring his father forward at that juncture, and therefore he said nothing to him or to anybody else on the subject. Thus it came to pass that after Zola's visit, the inquiry, "Where was Vizetelly?"—started, the writer believes, by Mr. Joseph Hatton—went the round of the newspapers; but while some raised it with the best of intentions, others repeated it with a malicious sneer, a circumstance which seemed to indicate that Vizetelly's son had really taken the wisest course. When the Journalists' arrangements had been ascertained, the Authors' Club dinner was fixed for September 28; and Zola, writing to Ernest Vizetelly on the twelfth, to express his approval, said: "Let me add, that I leave you full liberty. Whether those gentlemen invite me as a novelist or as President of the Société des Gens de Lettres, I shall in either case feel deeply touched and flattered. I am not a formalist; all genuine sympathy, in whatever respect, will go to my heart."

It was on September 20 that the novelist arrived in London[26] in the company of a dozen French journalists,—MM. Magnard, Scholl, Robbe, Xau, Mille, and others. Madame Zola and a few other ladies were likewise of the party. At Victoria station Sir Edward Lawson, now Lord Burnham, read in French an address of welcome, and Zola, when—like others—he had briefly responded, drove to the Savoy Hotel, where rooms had been engaged for him. The paper on anonymity which he read a couple of days afterwards to the journalists assembled in Lincoln's Inn Hall was, on the whole, well received. He admitted that the practice of signing political articles in France had undermined the authority of the press there, and tended to the destruction of parties; but, at the same time, said he, it had to be recognised that much of the inspiriting ardour of the political battle sprang from that same practice. On the other hand, as it was the custom for English political journalists to write anonymously, it might be well if they continued to do so, in order to preserve the power and authority of their press. But Zola pleaded strongly for signed articles in the departments of literary and dramatic criticism, pointing out, by the way, that such articles were indeed beginning to appear in certain English journals. One remark of his, to the effect that English newspaper men were well paid, elicited a loud roar of laughter, and there was considerable dissent when he likened some journalists to mere writing-machines at the beck and call of a superior. On that question some newspapers afterwards pointed out that on two occasions when there had been a change in the proprietorship of "The Pall Mall Gazette" the editors and the bulk of their staff had quitted the paper to uphold their opinions elsewhere. One may add that later, during the Boer war, various editors and others threw up their posts rather than write contrary to their convictions. One passage of Zola's address certainly seemed to have the full approval of his audience. It ran as follows: "To my thinking, when a writer does not sign his work, and becomes a mere wheel in a great machine, he ought to share the income earned by that machine. Have you retiring pensions for your aged journalists? After they have devoted their anonymous labour to the common task, year after year, is the bread of their old age assured to them? If they signed their work, surely they would find their reward elsewhere; they would have laboured for themselves. But when they have given their all, even their fame, strict justice demands that they should be treated like those old servants whose whole life has been spent in the service of the same family."

The journalists present having derided the suggestion that they were well paid, it seemed only natural that they should approve the idea of old-age pensions. At that time, of course, there already existed such organisations as the Newspaper Press Fund; and since then various pensions have been established by the Institute of Journalists; yet one may well wonder if there be even nowadays anything approaching adequate provision for the old age of journalists, of whom the great majority are able to save little or nothing of their earnings. It was undoubtedly this side of the question that most influenced Zola in his remarks on anonymity, which he regarded as being entirely in the newspaper proprietor's favour, for it enabled him, if he chose, to cast a writer adrift with nothing of the position which he might have held in public esteem as the result of his labours, if his articles had been signed. Briefly, in journalism as in other matters, Zola was on the side of the worker and against the capitalist.

No doubt when he was invited to London, purely and simply on account of the office he held, it was not foreseen that his visit would develop as it did. But although he was accompanied by several notable men he speedily dwarfed them all, becoming the centre of attraction at every gathering of the Institute of Journalists. There was a great dinner at the Crystal Palace, a reception at the Imperial Institute, and another, which was given to the journalists by the Lord Mayor, at the Guildhall. That historic building was then thronged to overflowing, and it was strange indeed—remembering all that had gone before—to see Zola and his wife marching in a kind of state procession, preceded by the City's trumpeters and followed by the Lord Mayor, the President of the Institute and other dignitaries, while some official who cleared the way called persistently: "Monsieur Zola! Madame Zola!" as though a couple of royalties were approaching.

Other entertainments were given at this time. Some of the theatres were thrown open to the guests of the Institute of Journalists; Sir Edward Lawson gave them a lunch at Taplow, there was a cordial little reception at the Press Club; while the Athenæum Club conferred honorary membership on Zola for the period of his stay in London. That last distinction was the most unexpected of all, and assuredly the Bishops belonging to the Athenæum cannot have known of it. At the Authors' Club dinner, which closed the round of "semi-official" gatherings, there were some eighty men of letters, with a sprinkling of publishers and others, present. When Mr. Oswald Crawfurd had proposed Zola's health—which he did in excellent French and very laudatory terms—the novelist, no orator, as he had carefully stated at the outset of his sojourn, read his reply, which may be given here as a specimen of his few public utterances, for he did not read or make more than a score of speeches in the whole course of his career.

"Since I reached London," he said, "I have received so many greetings and have so often been called upon to respond thereto, that I am a little ashamed to speak again. I need not, however, solicit your indulgent attention for any length of time. Indeed, in all modesty, I ask your permission to be very brief on this occasion. Nothing could have touched me more deeply than your very flattering invitation. I know that eminent writers are here assembled to extend to me the right hand of fellowship, and I feel that it is no longer the journalist but the novelist that is being entertained. (Applause.) Moreover, you have reminded me that in Paris I am the president of the Société des Gens de Lettres; so that in my person you honour all French literature. (Applause.) I should wish, therefore, to allow my own personality to disappear, and be nothing more than the delegate of my French brethren, to whom I shall attribute by far the greater part of the very cordial homage you have paid to me. I desire, indeed, gentlemen, to insist upon the feeling of fitting modesty that I shall carry away with me from all these functions. You have told me, Mr. Chairman, that, after conquering the world, I have come to conquer England. Will you allow me to reply that I know what I ought to think of my conquest? Amidst all the plaudits, I well understand that the opinion of your critics has not changed in regard to my works. Only, you have now seen their author, and have found him less black than report painted him. (Laughter and applause.) Then, too, you have reflected—'Here is a man who has fought hard and worked a great deal'; and belonging as you do to a great nation of workers, you have honoured work in me. (Applause.) Lastly, it has occurred to you that a man cannot have conquered the world—according to the facetious expression of two of your number—without being worthy of some praise. Works of a different order in art to your own may have affronted you, but you were too sensible to refrain from according them some recognition as soon as you understood how much effort and sincerity they embodied. I am leaving London, not, indeed, as one who has triumphed, but as a man who is happy at leaving some sympathetic feelings behind him. My heart overflows with gratitude for the hospitality, so extensive and so refined, that you have accorded me. Here I say good-bye, or rather au revoir (loud applause); and I say it, through you, to your compatriots. I wish, through you, to assure my brother authors, my fellow-novelists, that I shall never forget the truly royal reception that a mere French writer has received in this huge city of London, throbbing with life and so worthy of inspiring masterpieces. And, gentlemen, as at the close of every banquet it is right to propose a toast, I drink now alike to the novelists of England and the novelists of France, to the good-fellowship of all authors in one universal republic of letters. (Loud applause.)"[27]

Ernest Vizetelly was present at the Authors' Club dinner, and spent half an hour in the crush at the Guildhall, besides hearing Zola read his paper on anonymity. But he abstained from attending most of the other festivities. Every morning at an early hour he arrived at the Savoy Hotel to assist the novelist with his correspondence, the hundreds of applications for autographs and interviews, which poured in upon him, and after the first few days,—as soon as Zola had a little leisure,—he took him to see one and another of the sights of London. Mr. George Moore also escorted the Zolas to Greenwich; Mr. Andrew Chatto gave them a friendly luncheon; Mr. afterwards Sir Campbell Clarke acted as their cicerone at the National Gallery, and Dr. Garnett at the British Museum Library. There were also some interesting visits to the French Hospital and the French Club under M. Petilleau's guidance, an excursion with Vizetelly and a fellow-journalist to County Council and Rowton lodging-houses, Rothschild almshouses, various sweaters' dens, sundry Jewish homes in Whitechapel, and Italian ones at Saffron Hill. On the whole, however, Zola was not impressed by what he saw of London poverty; he declared it to be nothing in comparison with what might be found in Paris. There was much want, no doubt, but it struck him that the passer-by saw little of it. And to emphasise his meaning he reminded Vizetelly of the Parisian ragpickers' "Ile des Singes" and the woeful Route de la Révolte, which certainly has never had its parallel in modern London.

Westminster Abbey naturally interested him, though his visit was a very perfunctory one, owing to the haste of the usual verger with the sing-song voice. When one first entered the abbey, however, some afternoon service was in progress, and after standing and watching for a time, Zola whispered to Vizetelly: "I did not know this was still a Catholic Church." "It is Church of England—Protestant," Vizetelly answered, whereupon Zola seemed lost in astonishment. "Protestant?" he whispered again, "well, all that is very much like Mass to me." Then he shrugged his shoulders and led the way outside, where one waited till the service was over. At the National Gallery he was most interested in Turner, whom he called la palette incarnée and whom he regarded as being far superior to Claude. And he greatly admired Turner's water-colour sketches in the little rooms in the basement of the building, where he lingered for nearly a couple of hours. The British Museum Library also pleased him immensely, notably on account of its perfect arrangements which, were so superior, said he, to those of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. However, what he admired in London most of all was the Thames, at Westminster, at Waterloo Bridge, and again at the docks and away towards Greenwich. Of Hyde Park he formed a very poor opinion, while that royal barracks, Buckingham Palace, seemed to him a national disgrace: a view which most intelligent foreigners share.

On the whole, Zola was extremely well pleased with his stay in London, he had been received there with perfect courtesy, Sir Edward Lawson, Mr. Oswald Crawfurd, Mr. Charles Williams, then president of the London district of the Institute of Journalists, Mr. Lucien Wolf, and others had done all that lay in their power; and Zola on his side had at least made a breach in the wall of British prejudice. The result could not be otherwise than good, he said to Vizetelly; there would probably be less antagonism to his writings among English people in the future; but the point which interested him most of all was the effect his reception might have in Paris, notably among the members of the French Academy. He had been denounced more hotly in England than in any other country, he remarked, and the fact that English people were now beginning to take a more reasonable view of his work might possibly react on French opinion. But, as we know, the Academy did not disarm. The majority of its members would not suffer his presence among them on any consideration.

Moreover, he had scarcely quitted England when the fanatics once more raised their heads. At the Church Congress which assembled at Birmingham that year, Dr. Perowne, the Bishop of Worcester, had the effrontery to declare that "Zola had spent his life in corrupting the minds and souls not only of thousands of his fellow-countrymen and especially of the young but also, by the translation of his works, thousands and hundreds of thousands of young souls elsewhere." At the same gathering Mr. J. E. C. Welldon, then Headmaster of Harrow School and later Bishop of Bombay, denounced the novelist as "infamous," and besought the aid of Churchmen for the "National Vigilant Association," of which, according to "The National Observer," he, Mr. Welldon, was "a conspicuous ornament."[28] The Bishop of Truro, speaking at a church gathering in the west of England took a similar line, and complained bitterly that translations of Zola's horrible books were sold at the railway-station bookstalls, which, said he, would never have been allowed in the lifetime of that good man, Mr. W. H. Smith. Ernest Vizetelly answered the prelate in a newspaper of his diocese, pointing out that the only Zola translations sold at Messrs. Smith's bookstalls were those of "La Débâcle" and "Le Docteur Pascal" by himself, and that of "Le Rêve" by Miss Eliza Chase; and he defied the bishop to find in any one of those three books a single sentence that could give offence to any sensible man. Other correspondents reinforced Vizetelly; but the bishop, quite content with having uttered his slander, preserved absolute silence, that being a characteristic trait with some bishops—of various churches and countries—who, regarding themselves as very superior persons, seldom if ever offer reparation for the aspersions they may cast upon laymen. Yet the law of libel applies to them as to others, and it is perhaps a pity it is not enforced against them. But the lawyers say, or at least they said to Vizetelly: "It is useless to proceed against an English bishop. There is so much cant in this country that you would never obtain a verdict against him, however complete your evidence might be."

As for Bishop Perowne of Worcester he was answered in "The Speaker" by its contributor, Mr. A. T. Quiller-Couch, as well as by sundry correspondents, one of whom pointed out that this chartered slanderer "had not so much evidence to back his insinuations and assertions as would wrap round a mustard seed." Mr. Welldon was also dealt with at length and very ably by Mr. Quiller-Couch, the controversy in "The Speaker" being prolonged until the latter part of November.[29] Ernest Vizetelly was at first unaware of it, but a friend who, having little acquaintance with literature, read that Liberal weekly chiefly for its political articles, said to him one day: "You ought to see 'The Speaker.' There's a lawyer who is defending Zola and your father in it very vigorously. He is the kind of man your father ought to have had as counsel at his trial." "A lawyer?" Vizetelly replied, "why, what is his name?" "Oh! he only appends his initials 'A. T.' to his articles; but I felt interested, and so I consulted the law-list at my club. He's a Queen's counsel, by the way; and the only Queen's counsel whose initials are A. T. is the Hon. Alfred Thesiger, so he undoubtedly is the man." The truth, however, had suddenly dawned on Vizetelly, who began to laugh as he answered: "The initials are A. T., you say; but the writer puts Q. C. after them, does he not? I thought so. Well, I am much obliged to you for your information, but you are all at sea. Your Hon. Alfred Thesiger, Q. C., is none other than Mr. A. T. Quiller-Couch!" Then, while his friend was expressing his astonishment, Vizetelly began to think of fame.

In the controversy in question Mr. Welldon, who ended by admitting that he had read only three of Zola's books, received the support of clerics of various denominations. One of them, Canon MacColl, of Ripon, who would seem to have been then very fond of writing to the newspapers on all sorts of subjects, raised the old argument that even if Zola might have had some justification for publishing, for instance, "La Terre" in France, there could have been none for its issue in English and in England by Henry Vizetelly. No doubt the canon was right. As was set forth in a previous chapter the rural districts of England were and are terrestrial paradises, where immorality and beastliness were and are absolutely unknown. The observers who assert the contrary must be either liars or deluded fools. The clergy who are to be found in every village vouch for the high moral tone of their parishioners, and it follows that one must not believe those who chance to sit on juries at provincial assizes to try the various horrible cases, frequently from the aforesaid rural districts, which are never reported by a decorous press. Everything is for the best, then, in rural England, and the most perfect men in the whole world are the truth-speaking bishops who begin life in modest circumstances and end by leaving huge fortunes to their families, the many-sided canons fond of joining in every controversy, and the dogmatic clerical schoolmasters who take as their guide the saying attributed, perhaps erroneously,[30] to Richelieu: "Give me six lines written by the most honest man in the world, and I will find in them enough to have him hanged."

Henry Vizetelly, to whom his son forwarded "The Speaker" while the controversy continued, observed with some surprise Mr. Quiller-Couch's assertion that the public conscience would not permit a repetition of such proceedings as had been taken against him. He thereupon wrote to Mr. Quiller-Couch saying that in his opinion the public conscience could only find expression through the press, and that in the event of a new prosecution the press would again remain silent until the "National Vigilants" had secured a verdict, when it would once more join in approving the "vindication of the law." That view was shared by Vizetelly's son. Indeed, though Zola had been so well received in London, even by some of the provincial journalists who attended the Institute's Congress, though, too, newspaper men of education had come to a truer perception of his aims, and several wrote very favourably about his more recent books, it remained quite certain that he still had numerous enemies on all sides. At the close of that year, 1893, or more correctly on the first morning of the ensuing one, Henry Vizetelly died, and immediately afterwards another controversy began, this time in the London "Daily Chronicle." The chief features of the prosecutions of 1888 and 1889 were recalled by Robert Buchanan, Frank Harris, and George Moore, the first of whom dwelt on the attitude of the press with respect both to those proceedings and to Zola generally. Various protests arose, and, according to some people, it was quite untrue that the English press had ever flung mud at Zola or his publisher. The absurdity of that contention was made manifest by the publication, at that very moment, of several articles in which all the old lies and aspersions were repeated. These, it is true, appeared mostly in provincial journals; but two or three London prints did not hesitate to befoul yet once again the dead publisher as well as the recently banqueted novelist, whom G. W. Story, when recounting the controversy in "The New York Tribune," foolishly described as being "the most lewd writer in the world." It must be said, to Story's credit, that his article was a signed one, whereas the valiant scribes of the British press remained anonymous. They found, undoubtedly, that "anonymity in journalism" had its advantages, and wisely decided to cling to it. Since that time, however, the practice of signing critical articles has spread considerably and may some day become the general rule.

[1] Sherard, l. c., p. 228.

[2] His play "Madeleine" (originally called "La Madeleine") which he had vainly offered to the Gymnase and Vaudeville theatres in 1866, and which he had afterwards turned into a novel, "Madeleine Férat" (see ante, pp. 99 and 107) was produced with indifferent success at the Théâtre Libre in 1889—first performance, May 2.

[3] The writer believes it is called the Schveninger cure.

[4] About $600.

[5] "Le Rêve," Paris, Charpentier, 1893, 18mo, 310 pages. Some copies on Dutch, India, and Japanese papers. Eighty-eighth thousand in 1893; one hundred and sixteenth thousand in 1903. Illustrated edition: Flammarion, 1888, 4to; illustrations by Carlos Schwob and Métivet; one hundred and fifty copies on Dutch paper. Was sold in parts at 10 centimes. Jeanniot had illustrated the story in "La Revue Illustrée," which paid Zola one thousand pounds for the serial rights.

[6] First performed at the Opéra Comique, June 18, 1891.

[7] M. Eugène Fasquelle had now acquired an interest in M. Charpentier's publishing business, which he ultimately purchased.

[8] This was the result of having rid himself of his obesity.

[9] The allusion is to the house in the Rue de Bruxelles (21 bis), which Zola made his Paris home until his death.

[10] In his later years Zola kept Christmas and New Year's Day at Médan, and then usually had a house-party there.

[11] "La Bête Humaine," Paris, Charpentier, 1890, 18mo, 419 pages. Some copies on Dutch, India, and Japanese papers. Eighty-eighth thousand in 1893; ninety-ninth thousand in 1903.

[12] It is notorious that Taine, who led a section of the Academicians, that of the "university men," opposed Zola because he used vulgar and even slang words in some of his writings. Taine, moreover, was in full sympathy with the aristocratic element in the Academy with respect to its endeavours to make the institution a kind of deadly-lively social club.

[13] At subsequent elections he was defeated by Pierre Loti, Henri de Bornier, Thureau-Dangin, Ferdinand Brunetière, etc.

[14] "L'Argent," Charpentier, 1891, 18mo, 451 pages. Some copies on Dutch, India, and Japanese papers; eighty-third thousand in 1893; eighty-ninth thousand in 1903.

[15] "Journal des Goncourt," Vol. VIII, p. 141.

[16] Towards the close of the summer he allowed himself a holiday and repaired to the Pyrenees with his wife. It was then (September) that he first visited Lourdes and was struck by the sight of the pilgrimages. It immediately occurred to him that they would supply a good subject for a book, and to study them more closely he returned to Lourdes in the summer of 1892.

[17] The writer must admit that he has seen neither, but he has found one catalogued under the names of M. Claretie, the other under that of M. Camille Etievant. Both had appeared before 1885. It is of course possible that Zola had never heard of them.

[18] "La Débâcle," Paris, Charpentier and Fasquelle, 1892, 18mo, 620 pages; one hundred and seventy-sixth thousand in 1893; two hundred and seventh thousand in 1903. Illustrated edition: Paris, Flammarion, n. d., 4to, 527 pages; illustrations by Jeanniot; ninety copies on India, Japanese, and Dutch papers. The Bavarian Captain Tanera attacked the book in "Le Figaro," September 19, 1892, and his communication was reprinted by Lemerre, 8 pages, 8vo. Zola's answer to him, "Retour de Voyage," was also published by Lemerre, 1892, 18mo, 21 pages; forty copies printed, all numbered, those bearing odd numbers being on Dutch paper.

[19] Abbreviated from Sherard, l. c., p. 251 et seq.

[20] It paid him £1,400 = about $7,000.

[21] "Le Docteur Pascal," Paris, Charpentier and Fasquelle, 1893, 18mo, 390 pages; some copies on special papers; eighty-eighth thousand in 1893, soon after publication; ninety-fourth thousand in 1903.

[22] A translation of the address in question (made by the present writer) appeared in "The New Review," No. 50, July, 1893, under the title of "Life and Labour." Besides expounding the gospel of work, Zola answered the writers of Brunetière's coterie who had started the nonsensical cry of the "bankruptcy of Science."