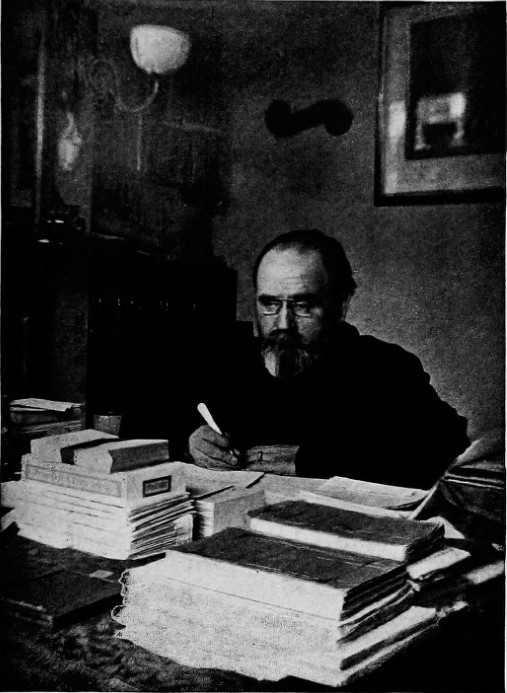

Émile Zola writing "Fécondité" at Walton-on-Thames, 1898 —Photo by V. R. Vizetelly

Zola's defence with respect to "Rome" will be found in a volume called "Nouvelle Campagne,"[12] which contains a number of articles he contributed to "Le Figaro" in 1896. They are of all sorts. The first, on the opportunism of Leo XIII, foreshadows the denunciation of the Roman Catholic Church which eventually appeared in "Vérité"; while another, called "Dépopulation," contains the germ of "Fécondité." There are various papers on the professional interests of literary men; a couple on Zola's love of animals, which was very marked throughout his life, and an incisive one, called "The Toad," in which he railed at the people who sent him abusive letters and the newspaper men who pursued him with pinpricks. Then, in a paper on a Parisian clairvoyante, a certain Mademoiselle Couesdon, who pretended to be in direct communication with the archangel Gabriel, he commented on the childishness of the imposture and deplored the senseless eagerness with which people imagined they would discover the secrets of the invisible by consulting a semi-hysterical girl. At the same time he admitted that such was the trend of the modern mind; and, after all, as people could only satisfy their yearnings in this way, one must let them do so, said he, pending the time when science would nourish the world with the bread of truth. However, the most notable article in the volume was certainly the one entitled "For the Jews," in which for the first time Zola gave expression to his surprise and disgust at the progress of anti-Semitism in France. In that campaign, the Dreyfus case, which at first had been merely an incident, was soon to become everything, for Colonel Picquart was now (July, 1896) making important discoveries which convinced him of the innocence of Dreyfus and the guilt of Esterhazy. That was as yet unknown to Zola, who did not begin to intervene until late in the autumn of the following year. Thus, in protesting against the anti-Jewish agitation which had been growing and spreading for some years past, he treated the question from a general point of view without mentioning the unhappy prisoner of Devil's Island. And here one may well call a halt to consider the state of affairs which had prompted Zola to raise his voice on behalf of a community with which he had no connection whatever, either racial or religious, but which he defended by virtue entirely of the guiding principles of his life,—the principles of truth and justice.

[1] "Enquête Médico-Psychologique sur les Rapports de la Supériorité Intellectuelle avec la Névropathie. Introduction générale. Émile Zola," by Dr. É. Toulouse, Paris, 1896.

[2] "Journal des Goncourt," Vol. VI, p. 254.

[3] According to Dr. Toulouse, Zola was less keen than most people in detecting odours, but he had a "smell memory" and could remember objects by their scent.

[4] Published in 1893.

[5] He showed great sensitiveness to all cutaneous impressions. He could not wear clothes in any degree tight, or lie in bed "tucked in." As a rule he slept for seven hours, and on awaking he constantly complained of pains in one and another part of the body, this being a symptom common among those who are liable to nervous affections.

[6] Not in the work previously quoted, but in a paper he wrote after Zola's death ("Le Temps," October, 1902).

[7] "Westminster Review," January, 1891, "Patriotism and Chastity," p. 2.

[8] "Enquête sur l'Évolution Littéraire," by Jules Huret, Paris, 1891.

[9] "Lourdes," Paris, Charpentier, 1894, 18mo, 598 pages. Seventy thousand copies sold on publication; one hundred and fifty-fourth thousand in 1903.

[10] "La Vraie Bernadette de Lourdes," Paris, 1894.

[11] "Rome," Paris, Charpentier and Fasquelle, 1896, 18mo, 751 pages. One hundredth thousand on sale in 1898; one hundred and sixth thousand in 1903. In the case of this book and subsequent ones, the sales from 1897 onward were largely affected by the unpopularity which Zola reaped from his participation in the Dreyfus case.

The growth of anti-Semitism in France—The Jews in Paris—The Union Générale—Drumont, "La France Juive," and "La Libre Parole"—Clerical plotting—Accusations against the Jews—Anti-Semitism in the army—Zola begins his novel "Paris"—His idea of a novel on ballet girls—"Messidor"—Facts and documents concerning Dreyfus submitted to Zola—He resolves to intervene—His articles in "Le Figaro"—His "Letter to Young Men"—He is hissed at Daudet's funeral—His "Letter to France"—The Esterhazy court-martial—Character of Esterhazy—Zola writes his letter "J'Accuse"—Some extracts from it—Its reception—Riots in the provinces and Algeria—Incidents of the turmoil in Paris—Zola prosecuted—Foreign sympathy—His counsel, Maître Labori—Clericals and Nationalists at work—The trial at the Paris Assize Court—A few of the facts it elicited—Zola mobbed—His body-guard—Madame Zola at the trial—Zola's declaration to the jury—A glance at Labori's great speech—Reception of the verdict—Publication of "Paris"—Zola's conviction quashed—New proceedings—First trial at Versailles—Incidents of the campaign—The handwriting experts secure judgment against Zola—Zola's letter to M. Brisson—Second trial at Versailles—Zola leaves for London—His sojourn in England—His English homes—Some of his notes to Vizetelly—Death of his pet dog—His visitors—Incidents in France—Zola's return to Paris—His manifesto "Justice"—Return of Dreyfus to France—The Rennes court-martial—Zola's manifesto "The Fifth Act"—His letter to Madame Dreyfus—Dreyfus pardoned—"Fécondité" published—Zola's trial repeatedly postponed—Zola's protests against the Amnesty—His sacrifices for the cause—The medal struck in his honour.

The emancipation of the French Jews dates from the great Revolution. At the assembling of the States-General in 1789 they entered on a brief and victorious struggle, in which their chief ally, curiously enough, was a Catholic priest, the famous Abbé Grégoire. From that period until the Third Republic, established in 1870, there was never, it would seem, any really considerable Jewish question in France. A little trouble occurred in the time of the first Napoleon. Some Jews were certainly mixed up in the financial scandals of Louis Philippe's reign, and Toussenel's work, "Les Juifs, Rois de l'Époque," was the result. Rascality was occasionally manifested also by some of the Jews who became prominent in finance during the Second Empire; but the presence of the Jews generally, in the midst of the community, excited no alarm. After the war of 1870, however, the number of Jews in France increased considerably, the new arrivals being chiefly of German, Austrian, Swiss, or Alsatian nationality. Most of them settled in Paris, where they engaged in a variety of professions and avocations, showing themselves, as a rule, shrewd, hard-working, and orderly members of society. About the same time some thousands of French Jews—participating in a movement which characterised the earlier years of the Third Republic, the so-called conquest of northern by southern France—also flocked to the capital. "Le Midi monte" was in those days a favourite saying, echoed by Alphonse Daudet in his "Numa Roumestan" with reference to all the Gascons and Provençals who then invaded Paris and came to the front there in politics, art, literature, and social life. The descendants of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews, who in the sixteenth century had settled in southern France, at Bordeaux, Avignon, and other cities, joined in the great migration to the capital, and thus ten years after the Franco-German war there were three or four times as many Jews in Paris as there had been previously.

But they were peaceable citizens and for the most part stanch Republicans. They remembered that the Revolution had given them emancipation, and they did not desire the restoration of any monarchy which might take it from them, or of any empire with an adventurous policy which might plunge the country into war and interfere with their avocations. Many of them, no doubt, had a comparatively low ideal in view, that of quietly prospering in their business; but an element of that kind is desirable in a community like that of Paris, which numbers many firebrands in its midst. Besides, it is not too much to say that, on more than one occasion, the Jews of Paris helped to save the Republic by throwing all their influence into the balance on the side of law and order, as, for instance, during the Boulangist turmoil.

However, for some years previous to that agitation, an anti-Jewish feeling had been growing up in Paris. The ultra-Catholics, the Royalists, and other malcontents resented the spread of Jewish influence; and two financiers, named Bontoux and Féder, availed themselves of that disposition to found a great Christian Bank, the Union Générale, which, it was hoped, would deprive the Jewish—and also the Protestant—financiers of a large proportion of their customers. Pope Leo XIII blessed that bank, and invested in it some millions of francs—the fruits of Peter's pence—which the pious Bontoux promised to restore to him fourfold. But the director of the Union Générale unluckily fell out with a great financier, M. Lebaudy, the millionaire sugar refiner, who though he was nominally a Catholic cared nothing for the advancement of the Church or of the French aristocracy, which had invested large sums of money in the Bontoux bank. At last, after some prodigious Bourse gambling,—such as Zola described in "L'Argent,"—the Union Générale was smashed by M. Lebaudy, who raked in by far the greater part of the spoils.

Undoubtedly there were some Jewish and also Protestant financiers with him, but it was he who engineered the work of destruction which ruined several members of the French aristocracy, and swallowed up the savings of many good Catholics in modest circumstances who had foolishly taken financial advice from their priests. Nine out of ten attributed the disaster to the Jews exclusively, and it was virtually from that hour that people began to talk of the so-called Jewish question. It was discussed at first in the Royalist and Clerical newspapers, which pictured the Israelites as the great enemies of those who wished to restore France to her ancient kings and her ancient faith. In another way the cry was taken up by some of the Radicals and Socialists opposed to Gambetta, in whose entourage several Jews figured prominently. These men, it was said, had nobbled the ex-dictator and were preying upon France. Thus the "question" gradually spread, assisted largely by the many unpopular tergiversations of the Opportunist party, first in Gambetta's time, and then over a term of years, some folk detecting the hand of the Jews, precisely as others detected that of the Jesuits, in everything that happened.

Moreover books were written on the question. Under the title of "Les Rois de la République," Toussenel's forgotten work was hashed up for popular consumption; and about the time when General Boulanger was coming to the front (1886), there appeared a book called "La France Juive," written by a certain Édouard Drumont, a scholarly man, who had long dabbled in antiquarian research. It so happened that nature had given Drumont a characteristically Jewish face, while his slovenly habits had imparted to him much of the appearance of one of those "old clo'" men, who, forty or fifty years ago, still perambulated the streets of London and Paris. He has repeatedly disclaimed, however, all connection with Jewry; and his personal appearance may therefore be merely some spiteful freak on the part of nature, which has cast him in the very mould of some of those whom he loathes and denounces.

"La France Juive," which as an attack on the so-called chosen race has never been surpassed in virulence and mendacity, created an uproar in some political and financial circles; but it did not at first make much impression on the general public. The Panama scandals began, however; millions of money were lost, the victims often being needy people; and helped by the circumstance that three or four of the principal culprits in those affairs were unquestionably Jews, and by the reissue of large portions of "La France Juive" in "Le Petit Journal," Drumont and his writings achieved great notoriety. A newspaper established by him, "La Libre Parole," became the recognised organ of anti-Semitism in Paris; and as this journal was financed by a certain M. Odelin, the administrator of the famous Jesuit school in the Rue des Postes, one may conclude that at an early stage at least some part of the French clergy gave support to the agitation; for the position of M. Odelin as a mere intermediary, or man of straw, was notorious.[1]

As time elapsed the attitude of the Clericals became yet more pronounced. Pope Leo XIII made advances to the French Republic. From his standpoint they may have been sincere; but in any case they tended to the supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church in France. On their side, the French Reactionaries, clergy and religious orders as well as laymen, could not give any frank and loyal support to the papal policy such as it was publicly stated to be, for it was foreign to their ideas, sympathies, and aspirations. If they made some outward show of acquiescence, this was only with the secret object of obtaining the mastery by feigning friendship and afterwards destroying the Republican régime. But the Republic of 1848 was not forgotten; the clergy had then adhered to the new order of things the better to strangle it; and thus, in spite of all the fair words of Leo XIII and the protestations of those who professed that they had rallied to the Republic in all sincerity, the more clear-sighted Republicans, like the advanced Radicals and the Socialists, remained full of distrust. Some years elapsed before matters really took shape. At first, indeed, the Pope merely coquetted with the Republic, reserving a formal pronouncement of his adhesion until an apparently decisive moment, and the clergy worked somewhat stealthily, assisted by those university men and others who abetted or accepted the retour offensif of mysticism in literature. Then, as time went by, the residue of the Boulangist party raised its head to propound various theories of Nationalism, Militarism, and anti-Parliamentarism, to the last of which the Panama scandals lent some force. For many years, undoubtedly, the trend of the masses had been towards free thought, but the sentiments of Nationalism and Chauvinisme appealed to many. The clergy had been striving to win France back to the fold by such devices as the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Lourdes miracles, and the money-boxes of Saint Antony, but whatever success might be achieved by those means here and there, it was not great enough to satisfy priestly aspirations. To all appearance there was not sufficient faith left among the masses for supernatural considerations to influence them in the required degree. Only earthly matters seemed to interest them, and it followed, therefore, that these must be put to use. Thus the clergy aided, abetted, and finally slipped into the Nationalist movement, which seemed the one most likely to yield the desired result.

It has been indicated that the great bulk of Jewish influence had hitherto been cast on the side of the Republic; and thus, although the Freemasons and the Protestants were also regarded as enemies by the Clericals, it was felt that they might be dealt with later, and that the first thing, the principal thing, was to destroy the power of the Jews. The ground, then, was gradually prepared for a campaign. Helped by the Panama scandals, "La Libre Parole," following "La France Juive," neglected no opportunity to traduce the Jews generally.[2] The Nationalist journals joined in the outcry, pointing out that many of the Jews domiciled in France bore German names, and arguing that, although they often asserted they were Alsatians, the assertion was usually a lie. In some instances, perhaps, they conspired with foreign Jews; and at all events they formed an imperium in imperio, clinging to their own kith and kin, their particular rites and usages, leading, as it were, a life apart from the rest of the community. Briefly, they were not Frenchmen, and were therefore not entitled to a Frenchman's rights.

As a matter of fact, many thousands of the Jews domiciled in Paris did not adhere strictly to Jewish practices. In the financial world several prominent families had not only become Catholic, but had contracted matrimonial alliances with the French aristocracy; while the whole tendency of those whom one may call the Boulevardian Jews, the members of the liberal professions, the authors, journalists, artists, and actors, was towards free thought and an intermingling with the bulk of the community.[3] In fact, in the present writer's opinion, before the more violent explosion of anti-Semitism in France, Paris was the city where one saw most sign of a blending of the Jews with the rest of the population—a very slow and gradual blending, no doubt, but none the less evident to careful observers.

But that was not taken into account by the Clerical and the Nationalist leaders in the campaign which both parties carried on, not, perhaps, by virtue of any formal alliance, but because both desired an effective war-cry which would appeal to popular passions and gain them recruits. In the end the Nationalists, though they denied it, were generally directed by the leaders of the Clerical party, who were men of much greater shrewdness and ability than the Déroulèdes, the Millevoyes, the Haberts, and the Guérins, and who thus contrived, in an indirect way, to employ the Nationalist movement for their own advantage. Both parties had the same immediate object in view—the destruction of the Republic, such as it existed—and thus they could well work together; but the Clerical leaders were resolved that, whatever might be the subsequent form of government, the real mastery should belong to Holy Church. Moreover some Nationalists were Clericals also. In 1891 Déroulède, the Nationalist chief, expressly accused the Jews of trying to "dechristianise" France; and in the following year a journal belonging to Deputy Delahaye, another Nationalist, fabricated a charge of "ritual murder," perpetrated, it was alleged, at Chatellerault. A little later the Marquis de Morès, Clerical, Nationalist, and anti-Semite all in one, insulted and challenged a number of Jewish army officers. "La Libre Parole" espoused his cause, and a movement to prevent Jews from serving as officers slowly set in, leading a couple of years later to the Dreyfus case.

In this connection one may remind the reader that an overwhelming proportion of the officers of the French army belonged to devout Catholic families, often aristocratic and royalist ones, which while thinking that a young man ought not to serve the government of the Republic in any political or administrative post were willing that he should accept a diplomatic appointment or join the army as an officer, for in such cases it was really France that he served, and not the hateful Republican régime. That distinction had been drawn already in MacMahon's time and was adhered to for many years, indeed until the clergy saw how advisable it was for their protégés to accept other public functions in order to fight the influence of the Jews and the Freemasons in various State departments. Thus many young men, trained by the Jesuits and others, were helped as far as possible into official positions without being restricted as previously to the diplomatic service and the army. Nevertheless, the last remained the favourite carrière among young aristocrats as well as among many young men of the upper bourgeoisie; and the great majority of these having been educated by ecclesiastics were, without doubt, prejudiced against the young Jews whom the regulations admitted among them. The prejudice was not, however, entirely religious, it was also a racial and a caste prejudice among those who belonged more or less to the old noblesse, and it was often in a sense patriotic, being inspired by a kind of distrust of Jewish rectitude. Indeed, even Jewish courage was questioned by some who forgot, or were not aware, that no little Jewish blood had flowed in the veins of such great fighters as Masséna, Soult, and Bernadotte.

The agitation against the French Jews had been growing slowly, then, for several years. An explosion was bound to come in any case, particularly as, with the exception of the one ministry which put down General Boulanger, the various French administrations over a lengthy period were deplorably weak. In the end the Dreyfus case became the battlefield of the parties which were contending for mastery. The outcry against the Jews was prompted, even among the Clericals, less by genuine religious motives than by political ones. The Jews were the pretext. Behind the onslaught on them, one on the Republic was being engineered. One may add that the anti-Semitism which arose in France was naturally assisted by that which prevailed in Austria and in Russia. Moreover, the Russian alliance became in certain respects a factor of importance; and the slumbering hatred of Germany on being roused in connection with Dreyfus influenced thousands of patriotic people.

Into the more intricate details of the case the writer does not propose to enter.[4] When this book was first projected he had some thought of reviewing a few curious points, but since then the victim of the great iniquity has applied for the revision of the proceedings at Rennes, and the matter is now before the judicial authorities. It is therefore best that one should confine oneself to narrating what Zola himself did to rescue Dreyfus from the hell in which he suffered for so many years—just recapitulating, as one proceeds, the facts which are essential for a proper understanding of Zola's rôle. At the same time one must not neglect his literary work, and the more important incidents, which, apart from the Dreyfus case, marked his career at this period.

It has been shown previously that the novelist paid little heed to the anti-Semites—whom he regarded as more turbulent than dangerous—until 1896, when he campaigned in "Le Figaro" and wrote an article entitled "For the Jews." He afterwards turned to his novel "Paris," concerning which he wrote to Vizetelly on December 11, 1896:

"My plan is finished, and I am about to begin the book. 'Paris' will be a novel, full of action, on all the different 'worlds' of Paris—the political, the intellectual, the society, the working-class worlds, etc. There will be no digressions or dissertations, but as much life and action as possible. You know that I never make promises without keeping them. The story will begin to appear in 'Le Journal' between October 15 and 31 (1897), and will be published as a volume at the end of January, 1898. Try to find an English newspaper to publish it, and you may also sound the Americans, telling them that you will supply the most lively and interesting book I have yet written."

About this time Zola also gave some attention to a four-act lyrical drama entitled "Messidor"[5], the music of which was composed by his friend M. Alfred Bruneau.[6] This work took the novelist to the Grand Opera House, where it was to be produced. He attended all the rehearsals, and evinced particular interest in the young women of the ballet, about whom—their appearance, manners, conversation, and lives—he accumulated a quantity of notes, with the object, so he afterwards told Vizetelly, of writing a novel about them, a novel which he would probably have called "Le Rat,"—rats de l'Opéra being the name under which the minor dancers of the house have long been known in Paris. It may be mentioned that a ballet designed for expressive character-dancing was a prominent feature of "Messidor," and that success largely depended on its efficient performance. But the authors found the corps de ballet wedded to the stereotyped forms of stage-dancing, the customary insipid jétés, pas de chales, entrechats, pirouettes, and so forth. Either from incapacity or in a spirit of obstinacy, the ladies of the opera would not modify their methods, and Zola, who had dreamt of revolutionising stage-dancing, of infusing into it some of the old Grecian fervour, which expressed the various passions so powerfully, was greatly disappointed. When "Messidor" was produced on February 19, 1897, it achieved little more than a succès d'estime. The ballet was praised by the critics, who judged it from the customary standpoint, but it was not what the composer and Zola had desired. Of course, no other result was possible. Years would be required to effect a revolution in stage-dancing, at least at the Paris Opera House.

After the production of "Messidor," Zola confined his attention to "Paris" for several months, and it was only on quitting Médan for his town residence late in the autumn of 1897 that he began to give serious attention to the Dreyfus case. The various attempts which both the Dreyfus family, through M. Bernard Lazare, and Colonel Picquart, influenced by his own discoveries, had made in 1896 to bring about a careful inquiry into the whole affair had yielded little result; but in 1897 the matter was taken up by M. Scheurer-Kestner, a much respected vice-president of the Senate, who came to the conclusion that the offence for which Dreyfus had been convicted had really been perpetrated by Major Walsin-Esterhazy. The latter received warning of what was brewing, and about the time when Zola moved from Médan into Paris, as mentioned above, the anti-Semitic press, having espoused Esterhazy's cause, was again thundering against the Jews. Some of Zola's friends interested in the Affair—as everybody called it—spoke to him about it at length. Before long, indeed, several documents were shown him at his house, and left a deep impression on his mind. He had no personal acquaintance with the Dreyfus family; he never saw Madame Dreyfus till she appeared in court during his own trial in February, 1898; and if on a dozen occasions, at the utmost, he met M. Mathieu Dreyfus and discussed the case with him, all such interviews took place posterior to his intervention. This was based on a dispassionate study of the facts and documents laid before him. He weighed them with his usual care, exactly as he weighed the documents he collected for his books; and it must not be imagined that the charges he eventually formulated were brought in any haphazard fashion. Zola's intellect, one may repeat it, was essentially systematic, and his judgment of facts and his logical powers were exceptionally good.[7] At the time of his trial in Paris there were many gaps in his information, undoubtedly, but its full extent was not then revealed, owing to the extraordinary course imparted to the proceedings by the judge and the military men. Various facts which were not publicly divulged until much later were kept back deliberately by the novelist's counsel, Maître Labori, as a matter of strategy, and it follows that Zola's action was far less quixotic than some people then took it to be.

It has been assumed occasionally that the novelist's intervention began with his famous letter, "J'Accuse." That, of course, is an error. One day in November, 1897, while he was out walking, he met M. Fernand de Rodays, the director of "Le Figaro," and they talked of the Affair together. Zola realised that M. de Rodays had arrived at much the same conclusions as himself, and he thereupon offered to write some articles. M. de Rodays assented, and on November 25—ten days after M. Mathieu Dreyfus had formally denounced Major Walsin-Esterhazy as author of the notorious bordereau[8]—"Le Figaro" printed a first contribution from Zola's pen, an article entitled "M. Scheurer-Kestner." On December 1 came a second, "Le Syndicat," which was followed on December 5 by a third, called "Procès-Verbal." Those articles were temperately worded; they appealed to the reader's judgment, and protested in a sober way against all attempts to inflame the popular passions. They certainly indicated a belief in Dreyfus's innocence, and asked for full inquiry; and on that account they angered the readers of "Le Figaro," who, being for the most part society people, sympathised with the Jew-baiters. Moreover the anti-Semitic and Nationalist prints, alarmed to find such a capable man as Zola espousing the cause of Dreyfus, at once attacked him savagely. He then had to withdraw from "Le Figaro," whose director, while adhering to his personal opinion in favour of Dreyfus, was unable to withstand the clamour of his readers and shareholders.

As it seemed doubtful whether any other paper of standing would print what Zola might write about the case, and as he desired to retain full liberty of action, he decided to continue his campaign with pamphlets, and a first was published on December 14. It was called a "Letter to Young Men"—that is the students and others, who at one moment ran about the streets shouting "Long live the army! Down with the Jews!" and at another assembled outside the homes of M. Scheurer-Kestner and others and hooted them. Zola expostulated with these young fellows, pointed out the folly and baseness of their conduct, and exhorted them to strive for truth, humanity, and justice. He declared, too, en passant, that the Chamber of Deputies had just covered itself with shame by a vote of censure which it had presumed to pass on those whom it accused of "troubling the public conscience by an odious campaign,"—that campaign being simply the appeal for truth and equity made by himself and others.

The pamphlet[9] stirred up the feelings of those for whom it was intended. They resented it, and began to demonstrate against Zola himself. Two days later, December 16, his good friend and fellow-novelist, Alphonse Daudet, died; and when Zola appeared as one of the pall-bearers at the funeral, so angry were the passions of the crowd that the respect due to the dead was forgotten, and groans and hisses were heard again and again as the cortège took its way to the cemetery of Père-Lachaise.

There, by the graveside, Zola read a pathetic farewell to his departed friend and comrade, of whose corpse, in accordance with usage, he had been one of the watchers a few nights previously. His hand shook as he fingered his manuscript, and there was poignant emotion in his voice when he evoked the memory not only of Daudet, but also of those who had gone before,—Flaubert and Edmond de Goncourt. "They were giants, good giants, artisans of truth and beauty," he said; "and now, great even as they were, of equal stature by virtue of the work he accomplished, Daudet has gone to join them in the grave, to repose beside them like a brother, in the same glory. We were four brothers: three have departed already, I remain alone."

Doubtless his feelings of loneliness were intensified by the groans, the cries he had heard, the ill-disguised hostility also of some of the mourners around him. But Zola was a stubborn man, great by reason of that very stubbornness. No attacks, no insults, no sufferings, could ever turn him from any purpose that he resolved upon in the plenitude of his intellect, guided by his sense of right and wrong. Soon after Daudet's funeral, that is on January 6, 1898, he issued another pamphlet, this time a "Letter to France,"[10] in which, after referring to the approaching arraignment of Major Walsin-Esterhazy before a court-martial, he protested against the violence of the press, and while disclaiming all idea of insulting the army, pointed out the dangers of militarism, the threatening shadow of the sword, which, unless France were careful, would lead her to dictatorship. Behind all else he showed the Church bent on reviving theocracy and intolerance. And with respect to the Affair itself, after complaining that the public mind had been poisoned against those who had resolved to elucidate the truth, he pointed out that if Dreyfus had been condemned on a document written by another (Esterhazy), whose guilt could be proved thereby, a revision of his case would be an imperative, logical necessity, for there could not be two persons condemned for the same crime. Besides, Dreyfus had been legally condemned on the bordereau alone—the only paper shown to his counsel—and even if there were other papers which in defiance of the law had been kept secret, who could refuse revision if it were proved that the bordereau, the one known, acknowledged document, was from the hand of another man?

But the French War Office was determined that the authorship of the bordereau should not be brought home to Walsin-Esterhazy. General Saussier, Military Governor of Paris, one of the few unprejudiced army chiefs of that time, had ordered a prosecution, but the investigations were carried out by the unscrupulous General de Pellieux, behind whom was the even more unscrupulous Colonel Henry of the Intelligence Bureau, and the acquittal of Esterhazy was virtually prearranged. The charge against him—as preferred by M. Mathieu Dreyfus—was that of having written the bordereau for which Alfred Dreyfus had been condemned, but at the court-martial of January 10 and 11, 1898, that definite accusation was never considered. The proceedings were turned against another officer, the gallant Colonel Picquart, who had been the first to discover indications of Esterhazy's guilt. For the rest, there was a deal of nonsense about a "veiled lady" and a "liberating document"; and at last Walsin-Esterhazy was unanimously acquitted.

He was, one may remind the reader, an illegitimate descendant of a famous Hungarian house, by reason of which connection he had assumed the title of Count. Bold, clever, cunning, unscrupulous, a thorough spendthrift, he had squandered his means and much of his wife's, also, in the gambling hells of Paris. He had begun his military career as a Papal Zouave. As a French soldier he was known to have been guilty of malversation in Algeria and to have forged certificates of his own exploits. He had written infamous letters about the French army to a relative, Madame de Boulancy. He had repeatedly found himself in desperate straits financially and had then borrowed money of Jews whom he had never repaid. He had practically deserted his wife and lived with a woman known as Mademoiselle Pays, who had been an habituée of the notorious Parisian dancing saloon, the Moulin-Rouge. She was certainly devoted to him, and he did not hesitate to eat her bread. There is nowadays no doubt at all that he and none other perpetrated the crimes for which Dreyfus had been sentenced. He had insulted and jeered at France in his private letters, and he had sold such of her military secrets as he could discover, not once nor twice, but repeatedly, over a considerable period, to Colonel von Schwarzkoppen, the German military attaché in Paris, and perhaps to Colonel Panizzardi, the Italian, and Colonel Schneider, the Austrian attaché, also. His guilt with respect to the bordereau was not perhaps absolutely established at the time of his acquittal, but his frauds and his general laxity of life were well known even then. Yet he was acclaimed as the "martyr of the Jews," cheered by a delirious crowd of officers and anti-Semites, embraced in public by young Prince Henri d'Orléans as though he were the very embodiment of the national honour. And on the morrow the gallant Colonel Picquart, who had striven to prove his unworthiness, was arrested and imprisoned in the fortress of Mont Valérien.

Zola now fully realised that the military authorities were resolved on a denial of justice. They dreaded an exposure of their blunders, their lies, and their illegal practices at the time of the conviction of Dreyfus. No ordinary means could bring about a manifestation of the truth. There remained "the sacred right of insurrection," which was not to be exercised lightly, for only in a great extremity could it be justifiably put to use. In Zola's opinion such an extremity had arrived. The sole means of eliciting the truth lay in carrying the Affair from the military tribunals to a civil court of justice, where some equity might perhaps be found; but this was only to be achieved by a virtually revolutionary method. Zola felt he must employ such a method. He could not hesitate. The call of truth and justice was too imperative. At once, therefore, directly he heard of the acquittal of Esterhazy, telling nobody but his wife of his intention, Zola drew up an open letter to M. Félix Faure, the President of the Republic. It was speedily despatched to the printing firm which had already printed the "Lettre à la Jeunesse" and the "Lettre à la France," the intention being to publish it as a pamphlet. A proof was already corrected when Zola thought of giving the letter a wider publicity by issuing it in a newspaper. A Radical journal called "L'Aurore," established in 1896 by M. Ernest Vaughan, previously one of the coadjutors of Henri Rochefort, had already taken up the cause of Dreyfus in a very courageous manner. Zola therefore offered his letter to M. Vaughan, who at once decided to publish it; and though it was also printed as a pamphlet it was never offered for sale in the latter form.[11] It appeared in "L'Aurore" on the morning of January 13, 1898, with the following heading—what French journalists call technically a manchette— in bold type: "J'Accuse...!" The idea was M. Vaughan's, and though the proper title, "A Letter to the President of the Republic from Émile Zola," was duly given, it was as "J'Accuse" ("I Accuse") that the letter became known all the world over.

It was a powerful piece of writing; those who only knew the Affair by what appeared on the surface judged it at the time to be too violent, excessive, but it was fully justified by subsequent events and discoveries. After expressing solicitude for M. Félix Faure and his presidency, on which so much mud had been cast by the Affair and its abominations, and setting forth that a court-martial had just dared to acquit, by order, an Esterhazy, a supreme blow to all truth and justice, Zola declared that on his side he would dare to do something, that is speak the truth, as he did not wish to be a tacit accomplice, for in that case his nights would be haunted by the spectre of an innocent man who was expiating beyond the seas, in frightful torture, a crime he had not committed. Next came an interesting summary of the Dreyfus case, a denunciation of the extraordinary methods and machinations of Colonel du Paty de Clam, by whom Dreyfus had been arrested, an account of the support which Du Paty had received from Generals de Boisdeffre, Mercier, and Gonse, a scathing exposure of the emptiness of the indictment on which Dreyfus had been convicted, and a scornful rejection of a certain secret document about "a scoundrel named D."[12] Passing to Esterhazy's case, Zola showed Picquart unravelling the truth but thwarted in his endeavours by Generals Billot, de Boisdeffre, and Gonse, because the condemnation of Esterhazy would necessarily imply a revision of the proceedings against Dreyfus. General Billot had not been compromised in them, he was a newcomer, but had taken the crimes of others under his wing in order to save what he deemed to be the interests of the military party. However, M. Mathieu Dreyfus had denounced Esterhazy, who after being greatly alarmed, ready for suicide or flight, had all at once become audacious, having received help from "a veiled lady," otherwise Du Paty de Clam, whose work, the conviction of Dreyfus, was now seriously imperilled, and who therefore had to defend it. Then Zola referred to the struggle between Colonels du Paty and Picquart, the latter of whom was at last accused of forging a petit bleu, otherwise a card-telegram, in order to ruin Esterhazy, in such wise that the one honest military man in the whole Affair was made a victim. The proceedings at the Esterhazy court-martial had been iniquitous, and yet in a sense only natural, for as Zola wrote:

"How could one hope that one court-martial would undo what another had done?... Does not the superior idea of discipline, which is in the very blood of those soldiers, suffice to weaken their capacity for equity? Whoever says discipline says obedience. When the Minister of War, the supreme chief, had publicly established, amid the acclamations of the National Representatives [the Chamber of Deputies] the authority of a decided case [la chose jugée], could one expect that a court-martial would give him the lie direct?... General Billot had given the judges [of Esterhazy] a hint, and they gave their decision in the same way as they might go into battle, that is, without arguing. The preconceived opinion which they brought to the bench was evidently this: 'Dreyfus was convicted of treason by a court-martial; he is therefore guilty, and we, as a court-martial, cannot declare him innocent; we know that to proclaim the guilt of Esterhazy would be to proclaim the innocence of Dreyfus.' Nothing could move them from this view.

"They have pronounced an iniquitous sentence which will forever weigh on our courts-martial, and cast suspicion on all their decisions. The first court-martial [that on Dreyfus] may have been wanting in intelligence, the second [on Esterhazy] was criminal, perforce. Its excuse, I repeat, is that the supreme chief had spoken, declaring the chose jugée to be unassailable, holy, and superior to man, in such wise that subordinates dared not affirm the contrary. People speak of the honour of the army, they wish us to love and respect it. Ah! certainly, yes, the army which would rise at the first threat, which would defend our French soil, the army which is compounded of the whole people, for that we have only affection and respect. But it is no question of that army, for the dignity of which we are justly anxious in our desire for justice. It is a question of the sword, the master that may be given us, perhaps, to-morrow. And to kiss devoutly the hilt of the sword, the fetish—no!

"As I have shown, the Dreyfus Affair was the War Office Affair. An officer of the Staff, denounced by his comrades on the Staff, and condemned by the pressure of the Chiefs of the Staff, cannot come back as an innocent man without virtually showing the whole Staff to be guilty. And so the War Office, by every imaginable means, by campaigns in the press, by communications, by influence, has screened Esterhazy in order to ruin Dreyfus a second time. Ah! what a vigorous sweep the Republican Government ought to effect in that Jesuits' den, as General Billot himself once styled it! Where can we find a truly strong and wisely patriotic Ministry daring enough to recast and renew it entirely? How many are the people who, at the thought of war, tremble with anguish, knowing in what hands the national defence is placed! And what a den of base intrigue, tittle-tattle, and waste has been made of that sacred asylum, where the fate of the country is decided! We are scared by the terrible light cast upon it by the Dreyfus Affair, that human sacrifice of an unfortunate man, a 'dirty Jew!' Ah! what a seething there has been there of madness and folly, silly fancies, practices only fit for some base police service, customs worthy of the inquisition and despotism, the good pleasure of a few gold-braided individuals setting their heels on the nation, and stifling its cry for truth and justice, under the mendacious and sacrilegious pretext of the interest of the State!"

Then, after censuring the press and the riff-raff of Paris, which supported the evil-doers, Zola declared it was a crime to poison the minds of the poor and lowly, to inflame reactionary passions and intolerance, sheltered the while behind that odious anti-Semitism of which France—the great France of the Rights of Man—would die if she were not cured of it. "It is a crime," he added, "to exploit patriotism for works of hatred, and finally it is a crime to make the sword one's God, when all human science is working for the coming sway of truth and justice." Next he praised M. Scheurer-Kestner, the great, good, upright man who, in his honest simplicity, had believed that a statement of the truth would suffice for justice to be done, and who was cruelly punished for his delusion. In like way Colonel Picquart, in reward for his scrupulousness and respectfulness, was covered with mud by his superiors. "One even saw this ignoble thing," said Zola, referring to Colonel Picquart, "a French tribunal, after allowing the prosecuting counsel to heap charges on a witness, to accuse him publicly of every kind of transgression, ordered the court to be cleared directly that witness was called in to explain and defend himself. I declare that this is one crime the more, a crime which will rouse the public conscience. Decidedly, the military tribunals have a strange idea of justice!"

Then after a final appeal to President Faure, who if he were the prisoner of the Constitution and his entourage, still had to discharge the duties of a man, Zola declared that he in no wise despaired of triumph, for truth was on the march and nothing would stop it. The Affair was only beginning. On one side were the guilty who wished to withhold the light; on the other the servants of justice who would lay down their lives in order that it might appear. When truth was buried underground, it gathered strength there, acquired such explosive force that on bursting forth it blew up everything. One would see, then, if present secrecy had not prepared the most resounding of disasters for some future date. And Zola concluded:

"I accuse Lieutenant-Colonel du Paty de Clam of having been the diabolical author of the judicial error, unconsciously I am willing to believe, and of having defended his baleful work for three years by the most absurd and culpable machinations. I accuse General Mercier of having rendered himself an accomplice, at least through want of firmness, in one of the greatest iniquities of the century. I accuse General Billot of having held positive proofs of the innocence of Dreyfus, and of having suppressed them, of having perpetrated this crime against humanity and against justice with a political object, and in order to save the compromised Staff. I accuse General de Boisdeffre and General Gonse of having become accomplices in the same crime, the former doubtless from clerical passion,[13] the other, perhaps, from that esprit de corps which makes the War Office a sacred and unassailable ark. I accuse General de Pellieux and Major Ravary of having made a wicked inquiry, that is an inquiry of the most monstrous partiality, of which we have, in the latter's report, an imperishable monument of naïve audacity. I accuse the three handwriting experts,[14] Sieurs Belhomme, Varinard, and Couard, of having made lying and fraudulent reports, unless medical examination should prove that they suffer from diseased sight and judgment. I accuse the War Office of having carried on in the press, particularly in 'L'Éclair' and 'L'Echo de Paris,' an abominable campaign in order to mislead public opinion and screen its transgressions. Lastly I accuse the first court-martial of having violated the law by condemning an accused man on a document which was kept secret; and I accuse the second court-martial of having covered that illegality by order; in its turn committing the judicial crime of knowingly acquitting a guilty person.

"In preferring these charges I am not ignorant of the fact that I expose myself to the penalties of Clauses 30 and 31 of the Press Law of July 29, 1881, which punishes libel. And it is voluntarily that I expose myself. As for the men whom I accuse, I do not know them. I have never seen them. I have no resentment or hatred against them. They are for me mere entities, spirits of social maleficence. And the act which I accomplish here is only a revolutionary means of hastening the explosion of truth and justice. I have but one passion—one for light, in the name of humanity, which has suffered so much, and which has a right to happiness. My passionate protest is but the cry of my soul. Let them have the courage to bring me before an Assize Court, and let the inquiry be held in broad daylight! I wait."

This manifesto threw Paris into a state of uproar. Three hundred thousand copies of the number of "L'Aurore" containing it were sold,[15] and long extracts were reproduced by "Le Siècle," "La Petite République," and the few other newspapers which supported the cause of Dreyfus: the great bulk of the press, it should be mentioned, being on the other side. The Clericalists in particular now threw off all disguise. That same afternoon Count Albert de Mun, the Papal Nuncio's henchman, "interpellated" the government in the Chamber of Deputies, and by 312 votes against 122 carried a resolution calling on the authorities to put a stop to "the attacks on the honour of the army." The Prime Minister, M. Méline, announced on this occasion that it had been decided to prosecute Zola, but this hardly satisfied the more ardent Clericalists, one of whom, M. de Pontbriand, deputy for Nantes and an acolyte of the Archbishop of Paris, suggested a few days afterwards that all the members of the Dreyfus family and the leaders of the "Jew Syndicate"[16] should be cast into Mazas at once! Moreover, a public meeting held at the Tivoli Hall was largely attended by priests, Christian brothers, and seminarists of Saint Sulpice, who were granted special leave for the occasion; and long and eager were the shouts of "Down with the Jews!" raised by these ecclesiastics, who were finally routed by some Anarchists among the audience.

During the ensuing fortnight demonstrations and riots took place in various parts of France, notably in cities where the priestly cause was strongly represented: Lyons, the city of Notre Dame de Fourvières; Marseilles, the city of Notre Dame de la Garde; Nantes, which had sent the anti-Semitic Pontbriand to represent it in parliament, and Bordeaux, where clericalism likewise numbered many adherents. Still more serious disturbances followed in Algeria, where Jews were beaten, wounded, in a few cases actually killed, their houses and shops sacked, and a quantity of their property burnt, or, in some instances at Algiers, thrown into the sea. Meanwhile Paris was in a state of turmoil, full of shouting crowds who, when they were not demonstrating before some Dreyfusite newspaper office, acclaimed every uniform with the cry of "Vive l'armée!" and pursued every suspicious nose with that of "Down with the Jews!" Zola was hooted under his windows, a few of which were broken, and the police had to protect his house. At the same time, while there was no little ferocity and violence, a great deal of Chauvinisme, as well as abundant hypocrisy and cowardice in certain political and bourgeois circles, the Esterhazy court-martial had quite disgusted a number of sensible, educated, thinking people, and ten members of the Institute of France, eight professors of the Paris Faculty of Medicine, a dozen of the Sorbonne, the Collège de France, and the École Normale, who were joined by numerous professors of provincial faculties and a good many scientific and literary men, now for the first time declared in favour of a revision of the Dreyfus case, thus bringing a welcome support to the cause for which Yves Guyot, Jean Jaurès, Francis de Pressensé, Georges Clemenceau, Joseph Reinach, Raoul Allier, and others were fighting in the press. This accession of strength to the Dreyfusite cause was greeted with sneers by the professional Jew-baiters, the Clericalist leaders, and the retrograde littérateurs of the Brunetière coterie who led or influenced the majority of the Parisians. They nicknamed their adversaries "the intellectuals," applying the word derisively; but it was a welcome nickname, and one well deserved by the little party of sensible men which counted in its ranks such notabilities as Bréal, Berthelot, Duclaux, Giry, Grimaux, Réville, Havet, Trarieux, Monod, Ranc, Passy, Paul Meyer, Anatole France, and Leroy-Beaulieu.

On January 20 Zola at last received a copy of the citation, which at the suit of the War Minister, General Billot, summoned him and M. Perrenx, the nominal manager of "L'Aurore," before the Assize Court of the Seine to answer, not the long string of charges contained in the letter to President Félix Faure, but only fifteen lines of it—those which denounced the Esterhazy court-martial for having acquitted the major "by order." All the rest was ignored. The desire of the military authorities was evident, they still wished to prevent any discussion of the Dreyfus case. Zola thereupon wrote to General Billot reiterating all his charges, but the only effect of this letter, which appeared in "L'Aurore," was to induce the three handwriting experts, Belhomme, Varinard, and Couard, to bring an action against the novelist claiming damages for libel. On January 22 the conduct of the military authorities in shirking Zola's principal accusations was raised in the Chamber of Deputies,[17] and wild uproar and fighting ensued until order was restored by the military guard. Two days later Count von Bulow, the German Foreign Secretary, declared in the Reichstag: "Between Captain Dreyfus and any German organs or authorities, no relations of whatever kind have ever existed." The Italian and Austrian governments made similar declarations; but nothing could check the folly of the French Militarists, or even of the Government, which well knew through the diplomatic agents of France abroad that in every court and chancellery of Europe Dreyfus was regarded as innocent and Esterhazy believed to be guilty. The foreign press shared that view, and expressions and testimonials of sympathy began to reach Zola from all parts of the world.[18] He received them gratefully; but could the sympathy of foreigners afford adequate solace when four out of every six Parisians were covering him with mud? Besides, that very sympathy led to yet more virulent attacks on him. It was fitting, said his enemies, that he should be supported by foreigners, who for the most part rejoiced to see the French army attacked and insulted! Well, he was welcome to their support. France cared nothing what foreigners might say. She would settle her own affairs in her own manner, regardless of the opinions of this man Zola, who was himself a foreigner, some kind of dirty Italian.