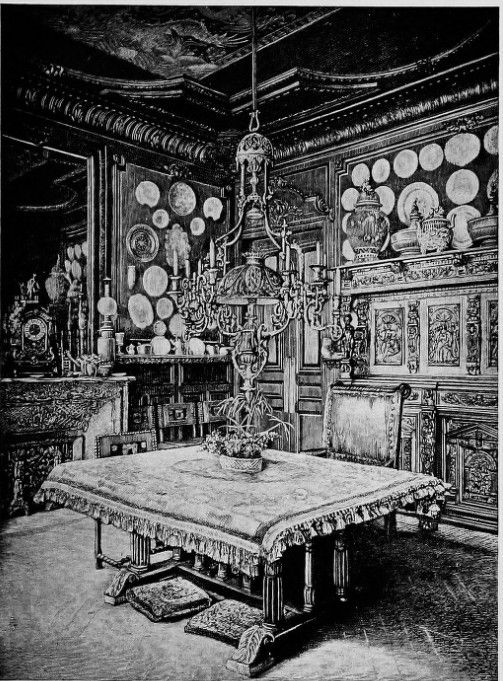

Zola's Dining-Room

Late in October, when the Cour de Cassation, accepting the question of revision in principle, began its famous inquiry, and when M. Brisson fell from office to be succeeded by M. Dupuy, Zola was removed from Addlestone[38] to the Queen's Hotel, Upper Norwood, where he remained till the end of his stay in England. He was still writing "Fécondité," to which he devoted all his mornings; and occupying a small suite of rooms in one of the pavilions of the hotel, taking his meals in private and holding no intercourse with his neighbours, his loneliness increased, though Norwood around him was teeming with life. At intervals, however, he now received a few visits from friends. The first who came was M. Yves Guyot, who had championed the cause of Dreyfus in "Le Siècle," which he directed, from the outset. With him was an English friend, Mr. J. H. Levy, of the Personal Rights' Association. Later came M. Jaurès, the famous French Socialist leader, another champion of the good cause; later still, Zola's old friend, M. Théodore Duret, the historian of the early years of the Third Republic. M. Fasquelle and M. Octave Mirbeau also saw the novelist at this time; and about Easter, 1899, Maître Labori paid a flying visit to England to consult him. There was one American visitor, Mr. Brett of the New York Macmillan Company, and a few English ones: Mr. George Moore, Mr. Lucien Wolf, Mr. Chatto and his partner, Mr. Percy Spalding. But those visits, besides being brief, were spread over a period of seven or eight months. Madame Zola certainly joined her husband for some part of the time, but the travelling, and more particularly the English climate, tried her health exceedingly, and for some weeks she was laid up. For the rest, the Vizetellys and the Warehams were frequently at Norwood, and there was still no little correspondence between the novelist and his translator. Here are a couple of notes written by Zola early in 1899:

January 3, '99.

My dear Confrère and Friend,—I have just telegraphed to you that the whole story about an English journalist having interviewed me is purely and simply a lie. I have seen nobody. Besides, there can be no question of extraditing me: they could only serve me with the judgment of the Assize Court. Those people don't even know what they write about. As for ——'s indiscretion, this is much to be regretted. I am writing to him. For the sake of our communications I have always desired that Wareham's name and address should be known only to those on whom one can depend. Tell Wareham to remain on his guard and never acknowledge that he knows my address.[39] Persevere in that course yourself. That will suffice for the moment. I will wait a few days to see if anything occurs, before deciding whether the correspondence arrangements should be altered. It would be a big affair; and I should afterwards regret a change if it were to prove uncalled for. So I repeat, let us wait.

Thursday, February 16, '99.

My dear Confrère,—You did right to refuse Mr. —— my address. I absolutely decline to see anybody. Whoever may call on you, under whatever pretext, show him the door and preserve the silence of the tomb. Less than ever am I in a humour to let people disturb me! As for Mr. Chatto and his partner, as you and they know, I shall be delighted to see them; but as you are also aware, my wife is at this moment very poorly indeed, and I am in a very low state myself. We should be sorry hosts, so kindly ask our friends to postpone the visit till a little later. Our amitiés to you and yours. Z.

On the day the second of the above letters was written, President Félix Faure died suddenly and under what seemed to be suspicious circumstances. It is probable that his seizure was caused by the shock he had experienced a few hours previously when certain revelations made to him by a foreign visitor of princely rank had dispelled his confidence in some of the prominent military men whom he had so long trusted and supported. The news naturally filled Zola with anxiety, for the future course of events might largely depend on the character of M. Faure's successor. Fortunately the choice of the French Congress fell on M. Émile Loubet, then President of the Senate. Other important incidents—M. Déroulède's attempt at a coup d'état, the transference of the revision of the Dreyfus case from the Criminal Chamber of the Cour de Cassation to the entire body—kept Zola in a nervous state throughout February and March. His birthday fell on April 2, and Vizetelly, finding it impossible to be with him on that occasion, wrote him a note to which he replied as follows:

My dear Confrère and Friend,—Thanks for your good wishes on the occasion of the anniversary of my birth. I feel deeply touched by them in the state of sorrowful emotion in which I am. You write me some very good and true things which go straight to my heart. And I thank you to-day for the devotion and the discreet attention which you have never ceased to show me since the day when I set foot on this land of exile. I shall expect you the day you please to select, and with kind remembrances to your family, I cordially press your hand.

ÉMILE ZOLA.

As the time for the decision of the Cour de Cassation drew near, the novelist became more and more restless. He finished "Fécondité" in May, and on the twenty-seventh of that month decided that whatever might be the judgment of the court, he would return to France directly it was given. Everything pointed to a favourable issue, and in that anticipation he drafted a declaration which he proposed to issue in "L'Aurore" on his arrival in Paris. On the evening of June 3 he received a telegram worded, "Cheque postponed," which, in accordance with previous arrangements, signified that revision had been granted and that Dreyfus would have to appear before a new court-martial. Had the words been "Cheque unpaid," they would have meant "Revision refused," while "Cheque paid" would have signified not only that revision was accorded but that Dreyfus would not even be tried afresh. For a long time previously Zola had been receiving similar telegrams which, in accordance with a plan devised by him, were full of hidden meaning.

M. Fasquelle and his wife were then in London, and it was speedily arranged that Zola, who was now in high spirits, should return to France with them on the following night, Sunday, June 4. This he did, quitting England without regret since he was going home; though he repeatedly acknowledged that everything possible had been done for his comfort, and that he had seen a great deal that interested him keenly. He appreciated the wonderful change which seemed to have come over the English press with respect to himself, and he was grateful also to the various persons who had recognised him and preserved discretion.[40]

About the hour when he reached Paris on the morning of June 5, "L'Aurore" appeared with his declaration "Justice!" a translation of which was issued the same day in "The Westminster Gazette."[41] After recalling under what circumstances he had been obliged to leave France, mentioning how he had been threatened and insulted and how cruelly he had suffered both before and during his exile, Zola reviewed the many developments of the Dreyfus case. And he continued:

"Now, as truth has been made manifest and justice has been granted, I return. I desire to do so as quietly as possible, in the serenity of victory, without giving any occasion for public disturbances. Those treat me unworthily who would confound me with the base folk who batten on public demonstrations. Even as I remained quiet abroad, so shall I resume my seat at the national hearth like a peaceful citizen who wishes to disturb none, but only desires to resume his usual work without giving people any occasion to occupy themselves further about him."

He disclaimed, he said, all reward or applause, for no merit attached to what he had done. The cause was so beautiful, so human. Truth had conquered, and it could not have been otherwise. Then he added:

"Moreover, my reward I have it already; it is that of thinking of the innocent man whom I have helped to extricate from the living tomb in which he had been plunged in agony for four long years. Ah! I confess that the idea of his return, the thought of seeing him free and of pressing his hands in mine, overwhelms me with extraordinary emotion, fills my eyes with happy tears! That moment will suffice to repay me for all my worries. My friends and I will have done a good deed for which every good heart in France will remember us gratefully. And what more could one desire?—a family that will love us, a wife and children who will bless us, a man who will owe it to us that in him has become embodied the triumph of equity and human solidarity."

Afterwards, referring to "J'Accuse," he said:

"Do people remember the abominable clamour which greeted my Letter to the President of the Republic? I was the insulter of the Army, a man who had sold himself, a man without fatherland! Literary friends, in their consternation and fright, drew away from me, abandoned me to the horror of my crime. Articles were indeed written which will weigh heavily on the consciences of those who signed them. Never, it was urged, had the most brutal of writers, a madman full of sickly pride, dared to address a more insulting and more mendacious letter to the Chief of the State! And now just reperuse my poor letter. I have become a trifle ashamed of it—ashamed of its discretion, its opportunism, I will almost say its cowardice.... I had greatly softened things in it; I had even passed some by in silence,—some which are manifest to-day and acknowledged, but of which I then still wished to doubt. To tell the truth, yes, I already suspected Henry, but I had no proofs. So I thought it best to leave him out of the case. And I divined other matters, for confidential information had come to me unsolicited,—information so terrible that, fearing its frightful consequences, I did not think that I ought to make it public. Yet now those confidences have been revealed, have become commonplace truisms. And my poor letter is no longer up to date; it seems quite childish, a mere skit, the paltry invention of some timid novelist, by the side of the truth, so superb and fierce.... There was not an unnecessary word in it, there was nothing but the grief of a citizen respectfully soliciting justice of the Chief of his country. But such has been the everlasting history of my writings—I have never been able to pen a book, a page even, without being covered with falsehood and insult, though on the morrow my assailants have been constrained to admit that I was in the right."

After indicating that he personally harboured no anger or rancour against anybody, Zola pointed out that, in the public interest, some example ought to be made of the wrong-doers, for otherwise the masses would never believe in the immensity of the crime. "But," said he, "I leave to Nemesis the task of completing her work. I shall not aid her." Then came an impassioned appeal on behalf of the noble and persecuted Colonel Picquart, for the good work would only be complete when justice had been done him. And Zola continued:

"All former political parties have now collapsed, and there remain but two camps,—that of the reactionary forces of the past, and that of the men bent on inquiry, truth, and uprightness, who are marching towards the future. That order of battle alone is logical; it must be retained in order that to-morrow may be ours. To work, then! By pen, by speech, and by action! To work for progress and deliverance! 'Twill be the completion of the task of 1789, a pacific revolution in mind and in heart, the democracy welded together, freed from evil passions, based at last on the just law of labour which will permit an equitable apportionment of wealth. Thenceforward France a free country, France a dispenser of justice, the harbinger of the equitable society of the coming century, will once more find herself a sovereign among the nations. And there exists no empire, however cased in mail it be, but will crumble when France shall have given justice to the world even as she has already given it liberty. I believe in no other historical rôle for her henceforward; never yet will she have known such a splendour of glory."

The conclusion followed:

"I am at home. The Public Prosecutor may therefore signify to me, whenever he pleases, the sentence of the Versailles Assizes condemning me by default to a year's imprisonment and three thousand francs fine. And we shall once more find ourselves before a jury. In provoking a prosecution I only desired truth and justice. To-day they are here. My case can now serve no useful purpose; it no longer even interests me. Justice simply has to say whether it be a crime to desire truth."[42]

Unfortunately subsequent events confirmed only some of Zola's generous anticipations. M. Dupuy fell from power on June 12, M. Waldeck-Rousseau succeeded him on the 22d, Dreyfus landed in France on July 1, and the new court-martial on him assembled at Rennes on August 8. His partisans were at first full of hope, but various incidents supervening (among others, a dastardly attempt to assassinate Maître Labori), no little anxiety returned. Zola had remained in seclusion at Médan,[43] glancing at the final proofs of "Fécondité," which was appearing serially in "L'Aurore," and thinking of his next work, "Travail." Meantime Vizetelly was repeatedly solicited by English editors to induce him to write something about the court-martial, but he was unwilling to do so for any foreign newspapers, and besides, as he put it, it was neither right nor possible to say anything until the verdict was given. He communicated with Vizetelly several times on these matters, on one occasion sending a card on which, in spite of all the bad rumours, he indicated his confidence in the result of the proceedings: "My dear friend," he said, "I will say nothing, and I beg you to say nothing in my name. One must wait firmly for victory."[44]

On September 9, however, the unfortunate Dreyfus was once more found guilty of the crime he had never committed. Zola, still at Médan, was profoundly shocked and horrified by the verdict, and again he published a declaration, "Le Cinquième Acte,"[45] in which he expressed his fear that the truth might fall on France from Germany in a manner which might have the most terrible consequences. The result of the trial certainly caused amazement all the world over. In Great Britain the indignation was extreme, and a proposal to boycott the Exhibition which was to be held in Paris in 1900 was agitated by several newspapers. Vizetelly was appealed to by some who felt that Zola might be able to quiet the outcry, and an offer of two shillings a word for an article which might run to ten thousand words, was made to him by the editor of a London newspaper. But even this proposal was declined by Zola, who wrote to Vizetelly on September 14:

My dear Confrère and Friend,—I do not take payment in France for my articles on the Dreyfus case, and still less would I accept money from a foreign newspaper. As for intervening between France and the world, I will not and cannot do so, for all sorts of reasons. Besides, in spite of the gravity of the symptoms, I do not believe that our Exhibition is seriously threatened. I still wish to believe that France will do what may be necessary to be in a position of dignity next May when she will receive her guests. All this between ourselves, this letter is absolutely for you alone. You would cause me the greatest grief by the slightest indiscretion.... Thanks for the English newspapers you have sent. I have just read them with keen interest. But all that does not frighten me much.[46]

Five days later the unhappy Dreyfus accepted the pardon offered him by President Loubet, and Zola then addressed a beautiful, pathetic letter to the poor martyr's wife, in which he gave her the assurance that his friends and himself would continue the battle until both her husband and France should be fully rehabilitated.[47]

In October "Fécondité" was published as a volume, and dealing as it did with a problem of national importance, the decline in the birth-rate and the massacre of infantile life in France, it attracted widespread attention. It was a very outspoken book, but a necessary one, and its exposure of the vices of married life was one to be applied to other countries besides France. But Vizetelly, who remembered the past and knew that Pecksniffs and Podsnaps still flourished in England, felt that the national cant would not suffer a plain statement of the truth. Some difficulty occurred therefore with respect to the translation of "Fécondité," the English version of which had to be considerably curtailed. In France the sale of the original work was assisted by the fact that after all the abominations of the Affair a certain number of Zola's former admirers were now gradually returning to him.[48]

His remaining share in the Dreyfus case may be dealt with briefly. The victim was at last free, restored to his wife and children; and thus a great part of Zola's object had been achieved. The charge against the novelist of having libelled the Esterhazy court-martial still had to be considered, but his trial was repeatedly postponed in consequence of the government bringing an Amnesty Bill before the legislature. Zola repeatedly protested against the measure, addressing long letters to both the Senate and President Loubet on the subject.[49] He did not wish to be amnestied but judged, and he thought it abominable that the same law should be applied to him and other defenders of the truth as to all the evil-doers who had persecuted Dreyfus, screened the scoundrel Esterhazy, and made use of every possible lie, forgery, and fraud, in order to obscure the truth, deceive the nation, and prevent justice from being done. But Zola's protests, whether by letter or by word of mouth, before the Senatorial Committee, which received him on March 14, 1900, were of no more avail than those of Dreyfus himself, M. Joseph Reinach, and Colonel Picquart. In point of fact M. Waldeck-Rousseau, the Prime Minister, was most concerned about the Clericalist peril behind the Affair,—the strenuous efforts which bishops, priests, and particularly religious orders had been making to capture France. They had used the Dreyfus case as a weapon; under their secret direction it had proved indeed a powerful one, and in M. Waldeck-Rousseau's opinion, before all else, it was necessary to deprive them of it. For that purpose he devised the Amnesty in the hope that he would thereby kill the Affair, put it out of the way, before dealing with the religious orders. The right course would have been to proceed against the compromised members of the General Staff, but after the Rennes verdict M. Waldeck-Rousseau had not the courage to do so. Besides, in that matter he was largely in the hands of his own War Minister, General de Galliffet. France was committed to the Amnesty long before General André arose to enforce obedience in the higher ranks of the army. And thus for political reasons a crowning iniquity was perpetrated. Impunity was assured to the Merciers, the Boisdeffres, the Billots, and all the others. At the most they lost their military positions. Every criminal action in the Affair was stopped and prohibited by the Amnesty Bill, which became law in November, 1900. The privileges of parties in civil actions were alone reserved, though at the same time Captain Dreyfus retained the right to apply for further revision and even rehabilitation whenever he might discover the necessary new facts. At that moment it was scarcely imagined in high places that he would do so. M. Waldeck-Rousseau, like many another before him, fancied that he had indeed killed the Affair; but at the time of writing these lines it is once more before the Cour de Cassation.

It should be added that, prior to the Amnesty, Zola had been acquitted of the charge of traducing Judet of "Le Petit Journal," who had so foully attacked his father's memory; and had moreover secured a judgment condemning the unprincipled journalist to pay him five thousand francs' damages. Judet, however, carried the case to the Appeal Court, and it long remained in abeyance. Finally, in a letter addressed to Maître Labori on March 7, 1901, Zola renounced all further action in this case as well as in one instituted against the handwriting experts for the purpose of setting aside the judgment by which they had levied an execution on the novelist's furniture. "Let them keep the money, let them go off with their pockets full," wrote Zola; "the bitter irony of it all will be the greater, and there will be yet a little more baseness in the Affair." For his part he did not wish that the great battle in a high and noble cause should end in sordid squabbles about sums of money. Though it was said that the Amnesty effaced everything, the Public Prosecution Office had retained the fines and costs levied upon him, and this, again, he regarded as monstrous; but he repeated that he did not wish to drag the cause through petty proceedings based on personal interest. The truth would not come from them, though assuredly it would come eventually.

That Zola spent a large amount of money in connection with the Dreyfus case is certain; for besides the costs of all the legal proceedings (criminal and civil) against him, which remained heavy notwithstanding the disinterestedness of Maître Labori, he often contributed considerable sums for objects connected with the cause. Moreover, although both "Paris" and "Fécondité" sold fairly well, thanks to the foreign demand, a very great drop occurred in the circulation of the novelist's earlier works, for which there had been a steady sale in previous years. It may be estimated that in 1897 Zola's income was between seven and eight thousand pounds. In 1898, the year of "J'Accuse," it was not more than a third of that figure. He sold the serial rights of "Fécondité" to "L'Aurore" for about half the amount he had been receiving for his works from other journals previous to the Affair; and it was not published as a volume till late in 1899, in which year also his income remained a low one. Indeed, it never rose again to its former figure. His book "Travail," of which something will be said in our next chapter, was only a demi-succès from the pecuniary standpoint. And as all this was, in the main, the result of his participation in the Dreyfus case, it will be seen that he made no small sacrifices for the cause he championed.

He found a sufficient reward, he said, in a quieter conscience, in the knowledge that he had done his duty as a man. Sympathy came to him, as one has mentioned, from many a foreign land, and of course he was not without sympathisers in France, his fellow-fighters of that bataillon sacré which by degrees became a small army. Subsequent to his condemnation in Paris in 1898, the newly founded Ligue des Droits de l'Homme, which was destined to recruit many soldiers for the good cause, opened, in conjunction with the newspapers which supported it, a subscription for a medal to be offered to Zola in recognition of his courage. In a few days over ten thousand francs were collected, and a superb gold medal, bearing the effigy of the novelist designed by M. Alexandre Charpentier, and by its size, weight, and the quality of the metal unique in numismatics, was struck.[50] Zola however, was long unwilling to accept it, for victory was not yet won. At last, some time after Dreyfus was pardoned, he consented to do so; and the presentation took place at the offices of "Le Siècle," whose editor, M. Yves Guyot, was president of the subscription committee. Besides the Dreyfus family, Colonel Picquart, and the Laboris, many others who had fought the good fight were present; and in response to M. Guyot's address, Zola pronounced a short and feeling speech, towards the close of which he said: "Undoubtedly, if the question had only been one of saving an innocent man from his torturers, of restoring Dreyfus to his wife and children, our victory would be complete. The whole world holds him to be a martyr, his legal rehabilitation will soon follow—all that frightful story is surely ended! But there was another dear to us, one who was poisoned, in peril of death, and that dear and great and noble one was France. We dreamt of seeing her freed from ancient servitude, rising, with her artisans, her savants, her thinkers, to a new ideal, reconquering old Europe, not indeed by arms but by the ideas that liberate. Never had there occurred such an opportunity to give her a sound practical lesson, for we had set our hands upon the very rottenness that was eating into the cracking, decaying edifice, and we thought if we pointed it out that would be sufficient, that the house would be cleansed, rebuilt, properly and substantially. But in that respect we have been beaten. They have decided merely to pass a sponge over the rottenness, so that the timbers will continue to crack and decay till the house at last comes down. For that reason I am sad, for that reason I cannot sing victory. Dreyfus is free, but our France remains ill, feeling that she has not strength enough to bear the splendour of truth and justice. And yet I am hopeful, for I believe in her labour, in the power of her genius. A somewhat long period would have elapsed, perhaps, had I decided to await her complete recovery before accepting the medal which has been laid aside for so many months in the expectation of a beautiful dawn. So I accept it now with emotion and with gratitude. And I hope that I shall not die before I see, reflected in its pure gold, that rising dawn of supreme national glory which we have all desired."

[1] It was proved, in a court of justice, during the proceedings taken by the French government against the Assumptionist Fathers.

[2] It was for a while opposed by a journal entitled "La Vraie Parole," established by Dr. Singer, subsequently the initiator of the well-known "Jewish Encyclopædia." As time elapsed "La Libre Parole" was reinforced by another scurrilous organ, "L'Anti-Juif."

[3] The same may be said of many of the scientists.

[4]For them the reader may be referred to the "Histoire de l'Affaire Dreyfus"—a masterpiece of research, literary skill, and acumen—which M. Joseph Reinach is producing in several volumes. Paris, Fasquelle.

[5] "Messidor" was the tenth or harvest month in the calendar of the First Republic.

[6] The writer does not know when Zola wrote the libretto of "Messidor"; but it seems likely that he did so in 1894 or 1895, for M. Bruneau must have subsequently required considerable time for the music.

[7] "The Westminster Gazette" published on January 16, 1898, a letter from the present writer, in which he said, inter alia: "I regard Zola as a man of very calm, methodical, judicial mind. He is no ranter, no lover of words for words' sake, no fiery enthusiast.... If ever he brings forward a theory he bases it on a mountain of evidence, and invariably subordinates his feelings to his reason. I therefore venture to say that if he has come forward in this Dreyfus case it is not because he feels that wrong has been done but because he is absolutely convinced of it. Doubtless many of the expressions in his recent letter to President Faure have come from his heart, but they were in the first place dictated by his reason. It is not for me at the present hour to speak of proofs but most certainly Zola has not taken up this case without what he considers to be abundant proof."

[8] For the assistance of the reader who may have forgotten the details of the Dreyfus case one may mention that this bordereau was a kind of covering note, giving a list of certain memoranda and documents on French army matters which the writer said he was then forwarding to the person whom he addressed. This person, it has always been assumed, was the German military attaché in Paris. At all events it was from his lodgings or from the German embassy itself that the bordereau reached the Secret Intelligence Department of the French Ministry of War, then directed by Colonel Sandherr, a strong anti-Semite, and Major (later Colonel) Henry. The writing of this bordereau was attributed to Captain Alfred Dreyfus, the only Jewish officer on the General Staff of the Army, and he, after a summary inquiry made by Major (later Colonel) du Paty de Clam, was arrested on the charge of betraying military secrets to a foreign power. Such, briefly, was the origin of the case.

[9] "Lettre à la Jeunesse," Paris, Fasquelle, 1897, 8vo, 16 pages and cover, bearing, besides the title, the inscription: "Humanité, Vérité, Justice." Price, 10 centimes. The text is reproduced in the volume of Zola's writings on the Dreyfus case, entitled "La Vérité en Marche," which also contains the "Figaro" articles and most of the letters published in "L'Aurore," etc., until Zola ceased to take part in the Affair.

[10] "Lettre à la France," Paris, Fasquelle, 1898, uniform with the "Lettre à la Jeunesse." An English translation of these letters and of "J'Accuse," and a further letter to General Billot, is published by John Lane, London and New York, under the title of "Zola's Letters to France." Introduction by L. F. Austin. 16mo, xiii-45 pages.

[11] Zola says in "La Vérité en Marche" that the pamphlets remained warehoused. The writer believes that they were ultimately destroyed.

[12] One of the points on which the new revision proceedings (1904) have been based is that the initial D was substituted in the document for another letter, probably a T.

[13] General de Boisdeffre, the Head of the General Staff, was a devout Catholic and an extreme anti-Semite. He had been French ambassador in Russia and it was there that his hatred of the Jews had taken birth. Boisdeffre did not place Dreyfus on the General Staff, but found him on it upon taking office, the appointment having been made by Boisdeffre's predecessor, General de Miribel. Boisdeffre was largely under the thumb of Father du Lac, a Jesuit, his confessor, to whom he repeatedly confided matters connected with his duties.

[14] Those experts asserted that Dreyfus had traced the bordereau from Esterhazy's handwriting in order to saddle him with the guilt of it.

[15] A good many copies were bought by anti-Dreyfusites and burnt publicly in the streets.

[16] There never was such a syndicate. Said Zola to Vizetelly more than once: "It is a thousand pities there was none! Half the journalists who denounced us lived on bribes and blackmail. They would willingly have sold themselves. In fact, in some instances, indirect suggestions to that effect were made in the belief that we really had a syndicate and millions of francs at our disposal. I know that several prominent Jewish financiers paid large sums at the time to have their names kept out of the newspapers."

[17] The discussion was originally raised by M. Cavaignac, one of the evil geniuses of the Republican party, apropos of an alleged confession made by Dreyfus to an officer of gendarmerie, but M. Jaurès, the Socialist leader, profited by the opportunity to bring forward the prosecution of Zola.

[18] Mr. David Christie Murray, the novelist, gave a very interesting lecture on the bordereau at the Egyptian Hall in London, generously placed at his disposal by Mr. Maskelyne. In the course of his remarks Mr. Murray strongly praised Zola's attitude, pointing out that after toiling through poverty, privation, and obloquy, to fame and wealth, he braved imprisonment and ruin out of pure pity and love of justice.

[19] He was the son of a certain Delegorgue, who after being known as the "elephant hunter" in the days of Louis Philippe, became a great friend of Alfred de Musset with whom he often played chess at the Café de la Régence.

[20] In the above passage the able summary of the Dreyfus case (by Sir Godfrey Lushington, it has been said) published by "The Times," October 14, 1898, has been followed. For all the details of Zola's trial, see "Le Procès Zola, Compte Rendu in extenso," etc., 2 vols., 8vo, Paris, Stock, 1898.

[21] In France it is not necessary for all twelve jurymen to be of the same mind.

[22] M. Perrenx was sentenced to the same fine and four months' imprisonment.

[23] At the request of the English publishers Vizetelly had written suggesting that the book ought to be published as soon as possible, that is, while the author's case was attracting so much attention.

[24] "Paris," Fasquelle, 1898, 18mo, 608 pages. Some copies on Dutch and other special papers; a few presentation ones in 2 vols., 8vo. Eighty-eighth thousand in 1899; ninety-fourth thousand in 1903.

[25] "Souvenirs," by Henri Brisson, published by "Le Siècle," 1903. Zola's letter is in "La Vérité en Marche."

[26] So stated to Vizetelly by Zola a few days after his arrival in England.

[27] M. Perrenx also had to leave France, and the writer believes that he went to Belgium.

[28] The account of Zola's sojourn in England will here be brief, the writer having already given a full one in his book "With Zola in England, a Story of Exile," by E. A. Vizetelly, London, Chatto, and Leipsic, Tauchnitz, 1899. Further particulars will be found in various papers by the writer: "Some Recollections of Zola" ("Pall Mall Magazine," Vol. XXIX, No. 117, January, 1903) and "Zola at Wimbledon" ("Wimbledon and Merton Annual," No. 1, 1904). A full account of the Christmas Zola spent in England (1898) was given in "M. A. P., Vol. IX, p. 235:" "Émile Zola in Exile," by Marie Suzanne (Mrs. E. A.) Vizetelly.

[29] Of Messrs. Gregson, Wareham, Waugh, and Gregson, solicitors.

[30] It fortunately turned out that the lady was the wife of Mr. Percy Spalding of Messrs. Chatto and Windus, Zola's English publishers, and thus the matter went no further.

[31] Madame Zola had been expected, but, being watched, had been unable as yet to leave Paris.

[32] This note was signed "Émile Zola," but thinking that imprudent, he carried his pen violently over the signature, producing an extraordinary combination of blots and scratches. Sometimes he signed "Em. Beauchamp," at others "J. Beauchamp," and "B." Later, he ventured on a "Z." Very few of his notes of that time bear his name in full. Moreover, for fear of the Cabinet Noir (the petit bleu affair showed that one existed), his letters to Paris were usually addressed by Vizetelly to a person who transmitted them to those for whom they were intended.

[33] "With Zola in England," p. 135 et seq.