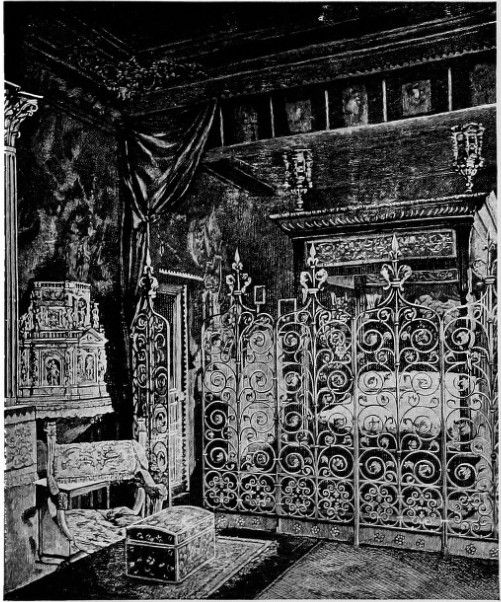

Zola's Bedroom

[34] Victor René Vizetelly, the writer's son.

[35] Zola had appealed against the first judgment, but on August 10 the Appeal Court confirmed the conviction, altering the original penalty (see ante, p. 463) to one of a month's imprisonment, a thousand francs' fine, and ten thousand francs' damages for each of the three plaintiffs.

[36] See notably his articles "Pour les Bêtes" and "Enfin Couronné" in "Nouvelle Campagne."

[37] £1,280 = $6,400.

[38] Before leaving Addlestone he wrote for the London "Star" a short story called "Angeline," based on a tale of a haunted house current at "Walton-on-Thames". The French text appeared in "La Grande Revue," edited by M. Labori. in 1899.

[39] In explanation of the above, it may be mentioned that Mr. Wareham's position as Zola's intermediary had come to the knowledge of a journalist through the indiscretion of a friend in Paris.

[40] On June 7 he wrote to Vizetelly: "Excuse me for not having written to you at once. I have been caught and carried off in such a whirl that I have not yet had a moment to myself. I made on the whole a very satisfactory journey, not a soul recognised me, and here everything is for the best."

[41] The numerous articles on the Dreyfus case which the writer contributed to that journal were largely inspired by Zola.

[42] The full text will be found in "La Vérité en Marche."

[43] He had written to Vizetelly, under date July 20, 1899: "I am at last sending you the promised photographs, and apologise for the delay. You can have no idea of the worries that have assailed me. I have often regretted the quietude of Queen's Hotel already. However, everything is going for the best, the happy dénouement is approaching, and I start for Médan on Tuesday to take a rest. I have read in 'Le Matin' your articles on my stay in England. They are très bien, they have skilfully remained within the limits which I asked you not to exceed. Thanks again. I press your hand affectionately. Émile Zola." The articles referred to were those reprinted as "Zola in England."

[44] A fac-simile of the card in question accompanies the present volume.

[45] See "La Vérité en Marche," p. 147 et seq.

[46] A fac-simile of the above letter is given with the present volume.

[47] "La Vérité en Marche," p. 163 et seq.

[48] "Fécondité." Paris, Fasquelle, 1899, 18mo, 751 pages. Some copies on special papers; a few in two vols. 8vo. Ninety-fourth thousand in 1901.

[49] See his letters in "La Vérité en Marche," p. 181 and p. 205; also others in "L'Aurore," March 10 and 15, 1900.

[50] It was, so to say, a medallion, its diameter being about 7 inches (183 millimètres), and its thickness about one eighth of an inch (3 millimètres). It weighed 5.80 pounds troy. On the obverse was the novelist's effigy with the inscription, Hommage à Émile Zola; on the reverse, the inscription, La Vérité est en Marche et Rien ne l'arrêtera, Émile Zola, 13 Janvier, 1898. A copy of the medal on a reduced scale (59 millimètres) was also given to Zola, and with the balance of the subscription money small copies in silver and bronze were distributed among the subscribers, others being sold to the public.

Zola's attempts at constructive writing—His evolution toward Socialism—Some further remarks on "Fécondité"—"Travail" and the pacific evolution of the working classes—Zola and the tastes of his readers—Publication of "Travail"—"L'Ouragan"—Zola's difficulties with "Vérité"—He is haunted by the Dreyfus case—He adapts it to "Vérité"—His evolution in religious matters—His Positivism—His opinion of the French Protestants—His last days—Announcement of his death—Account and cause of it—The autopsy—Madame Zola's illness—Reception of the news in France and abroad—Insults and tributes of sympathy—Preparations for the funeral—The question of military honours—Difficulties with Captain Dreyfus—The obsequies—A great demonstration—The speeches at the graveside—M. Anatole France's stirring oration.

Until Zola began his last series, "Les Quatre Évangiles," he had been, virtually all his life, a writer of the so-called destructive school, that is to say he had directed attention to an infinity of things which in his opinion ought to be swept away, but he had said little indeed of what he would set in their place. In like manner, within narrower limits, Charles Dickens and Charles Reade had exposed abuses without indicating remedies. Zola for his part long held that remedial measures were not of his province. It was for the legislator to devise them, and there was no call for the author to go beyond an exposé of the abuses which required redress. Time and circumstances gradually modified that view, and in his last years, while persevering in his destructive work, Zola made some attempt to couple re-construction with it. A suggestion of what was coming appeared already in the pages of his novel, "Paris," which concluded the trilogy of "Les Trois Villes." In that series he had shown Faith expiring, Hope a delusion, Charity a mockery, but at the same time he had felt that if those guiding principles were to be discarded, they must be replaced by others,—Fruitfulness, Work, Truth, and Justice.

The scheme was of earlier date than the Dreyfus agitation, and no trace of the latter is to be found in "Fécondité," the first volume in which it was unfolded. But as Zola proceeded with his work he was naturally influenced by all he had experienced and witnessed during the turmoil. As will presently be seen, the Affair eventually invaded his pages, but apart from that matter it hastened an evolution of his mind. He had begun life as an Individualist, it was as an unattached Socialist that he ended it, and this would have happened, no doubt, whether there had been a Dreyfus case or not. Without the Affair, however, the evolution might have remained less definite, less complete. The Affair showed him that the existing social edifice was in some respects even more rotten than he had previously believed. There could be no doubt of it, the facts were manifest; and it followed that there was now less call for exposure than for remedial measures. As his opinions with regard to such measures differed largely from those of the men in power, the call upon him was all the greater. He therefore tried to indicate broadly on what lines reforms might proceed, and to sketch the future effect which such reforms might have on the community.

It has been said that in his last works his imagination failed him, that it was quite spent, and that he could no longer have produced a work of art had he tried. That theory is wrong, based on ignorance of what was then in Zola's mind. If he had lived long enough to write the novel on the "Rat de l'Opéra,"[1] of which he talked so often to the present writer, the world would have seen that the powers of the novelist were undiminished. But in the great crisis through which France was passing Zola held that for a time, at all events, his duty lay in other work.

"Fécondité," of which some mention was made in the previous chapter, treated a subject which had long haunted him—in a measure for personal reasons—but it was, of course, from the national standpoint that he dealt with it in his book. The question of the decline in the birth rate and the mortality among infants had not only occupied the attention of French sociologists and scientists for several years, but various novels based upon it had already been written—novels indicating that the whole tendency of the times was to transform matrimony into legalised prostitution, in accordance with certain specious neo-Malthusian theories. Zola rightly held that unless that tendency were checked there could be no social regeneration at all. Thus he placed the subject in question at the head of his series. While he was preparing "Fécondité" in England the present writer was often able to glance at the documents, medical works, reports, letters from eminent scientists, and so forth, on which the novelist based his account of the noxious practices prevalent in various strata of French society, and he holds that far from "Fécondité" being an exaggerated picture it did not represent more than two-thirds of the actual truth. On the other hand, when Zola proceeded to sketch the healthy life which ought to replace the existing one, enthusiasm led him further than was necessary, though, after all, he did not go beyond the provisions of the "marriage-books" which the French authorities hand to every bridegroom at the conclusion of the marriage ceremony—books beginning with a signed and stamped certificate of the union just celebrated and continuing with enough blank forms to register the birth of twelve children—the number which Zola bestowed on his hero and heroine, Mathieu and Marianne.

Fruitfulness, said he, created the home, whence sprang the city; and from the idea of citizenship that of the fatherland proceeded. There could be no nation unless there were fruitfulness, which became, then, a first national duty. The second was work, which Zola considered under various aspects in his next novel, "Travail." He held that every man ought to work for his own support and that of his family, and he also regarded work as a panacea for many ills. But he turned more particularly to the consideration of the circumstances under which work was done in the modern world, to the condition of the toilers generally, the great capital and labour problem. In that connection he was greatly influenced by the state of France at the time he wrote, the onward march of Socialism, the innumerable strikes, the complaints, the demands rising on all sides. He felt that matters could not remain as they were. But though he was in the higher sense a great fighter he was the adversary of mere brute force; and dreading an armed collision between the classes, he tried to devise, to suggest, a pacific remedial evolution.

As he was unwilling to imprison himself or anybody else within the narrow and stringent bonds of certain forms of Socialism, it was to the broader and more generous ideas of Charles Fourier that he finally inclined, striving to adapt them to the needs of a new century. It is certain that some of his suggestions remained nebulous, that several were not strictly practical, but it should be remembered that at the outset of "Les Quatre Évangiles" he had announced that the series would form a kind of "poem in prose, divided into four chants." It would be unfair to neglect that statement, for it shows he did not intend "Fécondité" and "Travail" to be taken as severely practical works. They partook, as one has said, of a constructive character—-as opposed to Zola's earlier and purely destructive writings—but they were not intended to be the final plans of an architect or an engineer, or the ultimate provisions of a new code. They were the roughest of sketches, so to say, suggestions which here and there might be found useful by those who might have to solve the problems which they reviewed. And it must be at least admitted that their tendency was good. In "Fécondité" it was most healthful; in "Travail" it was most pacific and calming, Zola's manifest intention being to quiet the angry passions of the hour, to direct Labour towards peaceable courses in its quest for the fulfilment of its aspirations.

Such books cannot be judged as one would judge ordinary novels. They were, to a certain point, drafted in the form of novels in order that they might reach the great majority; but Zola, with superb disdain, now cast many of the rules and conventions of novel-writing aside. After the publication of "Travail," Vizetelly sent him word that the English translation had been regarded less as a work of fiction than as a combination of sermon and pamphlet, to which the reviewers and the public did not seem to take very kindly. Zola replied under date of May 8, 1901:

"I have never consulted the tastes of the public, and I am too old nowadays to modify my work in order to please it. I am writing these books with a certain purpose before me, a purpose in which the question of form is of secondary importance. I have no intention of trying to amuse people or thrill them with excitement. I am merely placing certain problems before them, and suggesting in some respects certain solutions, showing what I hold to be wrong and what I think would be right. When I have finished these 'Évangiles,' when 'Vérité' and 'Justice' are written, it is quite possible that I shall write shorter and livelier books. Personally I should have everything to gain by doing so, but for the present I am fulfilling a duty which the state of my country imposes on me."

Most of "Travail" was written in 1900, in December of which year it began to appear in "L'Aurore." In April, 1901, it was published as a volume.[2] A little later in the same year, the virulence of the Dreyfus agitation having subsided and public attention being turned to the Assumptionists and other religious orders, in connection with M. Waldeck-Rousseau's Association Bill, the director of the Opéra Comique in Paris thought the moment favourable for the production of a one-act lyrical drama, entitled "L'Ouragan," the prose libretto of which, set to music by M. Bruneau, had been written by Zola some years previously. "L'Ouragan" was not a particularly ambitious work and the moderate success it achieved was perhaps all that could have been expected for it.

After the production of that piece Zola began to consider the subject of his next book, "Vérité," which gave him no little trouble. It seems likely that when he first planned his series he had thought of showing in this particular volume that scientific truth, and not the assertions, delusions, and errors of religious systems, should be taken as the guiding principle of life. But the Dreyfus case, which had intruded into a few pages of "Travail," haunted him. He knew that it had supplied one of the most shocking exhibitions of mendacity that the world had ever witnessed; and it followed that "Vérité" ought not merely to inculcate a belief in scientific truth. It also ought to recall people to the practice of truthfulness in their every-day life. Thus Zola's subject expanded. He had always intended to show the evil effects of the training given to children in certain so-called religious schools, where, according to his view, their minds were perverted, deprived of all self-reliance by the intrusion of the supernatural. But the Dreyfus case had shown him there was more than that. The mendacity so current throughout the period of the Affair had come almost entirely from men trained by the Roman Church. Moreover that Church's share in the Affair, its hostility and its intrigues against the Republic under cover of the anti-Semitic agitation, were now every day more apparent. Zola had repeatedly declared that he would write no novel on the Dreyfus case, for he did not wish anybody to say that he had earned a single sou, directly or indirectly, by the Affair. But it was ever beside him, with its influence, its revelations, its lessons. And it seemed to him fit that everybody should understand that in one way and another such turmoil, frenzy, and mendacity would never have been possible if it had not been for the Roman Church. The case haunting him more and more, he gradually yielded to the obsession, resolving, however, to cast the military men on one side, for after all they had only been agents, in some degree the victims of their training. In lieu of them he would depict those whom he regarded as the real culprits. It had been settled that the book should deal with school life; and it would be easy to adapt a kind of Dreyfus case to such surroundings. A Jewish schoolmaster might be substituted for a Jewish officer, while as for the crime which it would be necessary to impute to him, there had been a terrible affair at Lille, not long previously, the murder of a little boy, in which a certain Brother Flamidien—who was spirited away by his colleagues—had been implicated. Some such brother would represent Esterhazy in Zola's work, Dreyfus being represented by Simon, the Jewish schoolmaster.

That Zola repeatedly hesitated with respect to this pastiche of the Dreyfus case is certain. In the summer of 1901 he wrote to Vizetelly that he was preparing "Vérité," but that none of it would be ready for several months, for he was still doubtful whether he would introduce certain elements into the work or not. Finally, as the only means, perhaps, of relieving his mind, he took the plunge, resolving upon an adaptation of the Affair on the lines one has indicated. Yet he again paused more than once, as he mentioned in another letter. That was written on September 12, when he further stated that he would have nothing ready until the ensuing month of January, 1902, when he wrote to Vizetelly:

"Thanks for your good wishes for the New Year, and pray accept ours for yourself and all your family. I find I shall not have 'Vérité' ready for publication as a book until next October, and that the feuilleton will not begin to appear until the early days of June. As you would like to have a few chapters in advance, however, I think I may be able to send the first ones about the end of next month.... I wish you good health, good work, and am very cordially yours,

"ÉMILE ZOLA."

Again there came delays, perhaps, because for the purposes of his book Zola was following the campaign against the religious orders.[3] At all events the proofs of the first four chapters were not sent to Messrs. Chatto till July 10, on which date the novelist wrote to Vizetelly that the serial issue would begin in "L'Aurore" on September 10. About this time, July, Zola had completed the actual writing of the work, and revised the proofs of Book I, the first forty pages of which were as good as anything he had ever penned. But as the work proceeded its hybrid character became manifest. As the Affaire Flamidien had suggested itself to Zola's mind it would have been better if the criminal part of the work had been confined to it. The grafting of the Dreyfus case upon another one led to various difficulties in the narrative, and the very restraint which Zola imposed upon himself in his veiled account of the real Affair was prejudicial to the general effect. In the writer's opinion the best part of the work was that describing the conflict between the hero Marc and his wife, Geneviève, the former a free-thinker, the latter a product of Catholic training, who after forgetting her faith amid her love, remembered it when the question of training and educating her daughter arose.

In that connection it may be mentioned that while Zola was in England during the Dreyfus case, he and Vizetelly in their strolls together discussed such matters more than once. Vizetelly had occasion to mention incidents well within his knowledge, which showed what serious trouble sometimes supervened when husband and wife were not of the same belief. Those conversations were doubtless remembered by Zola while he was writing "Vérité," in which, however, he described a far more dramatic and more painful situation than had been sketched to him. Chats of that kind led to discussions on religion generally. Vizetelly having mentioned various changes which had come over him in matters of belief, Zola replied by recounting some of his own experiences. Baptised a Catholic, he had made his First Communion, and though it was not true that he had ever been a choir-boy he had walked in religious processions. But a little later, rejecting now one dogma and now another, he had gradually freed himself from all such bonds, merely clinging for a time to such Deism as Voltaire suggested when he said or wrote: "Si Dieu n'existait pas il faudrait l'inventer." Would Voltaire have used such words, however, if he had lived in the nineteenth century, the age of science? Zola thought not. For his part, in religion as in literature and other matters, he had been unable to tarry long in any half-way house. He had at last largely embraced the Positivism which acknowledges only that which is manifest, and which neither accepts nor denies that which is hypothesis only. Zola had known Littré, Wybouroff, and others, and he had at least met Pierre Laffitte; but his creed, apparently, had come to him less directly than indirectly, that is filtered through the philosophy of Taine. For the rest, as a great admirer of M. Berthelot, he was a fervent believer in Science. In spite of the many limits to our knowledge nowadays, he held that Science would some day succeed in solving directly or indirectly the whole riddle of the universe. Nevertheless, though he could not believe in the supernatural such as it was expounded by the Christian churches, he fully understood that many should cling to such beliefs in their craving for some certainty and consolation. It seemed to him monstrous, however, that so many grossly superstitious practices should have been grafted on the elementary principles of Christianity, and that the Roman Catholic Church should be primarily an engine of political domination. At the same time he held the opinion that there was far more broadness of views among Catholics generally than among Protestants. The latter certainly had one good trait, their minds might be narrower, their self-righteousness might be almost repulsive, but their rigidity of principles at least stimulated them to truthfulness, whereof, said Zola, they had given conspicuous proof during the Dreyfus case. The French Protestants were only a handful, but they possessed the courage of their convictions; they had not hesitated to testify to the truth, whatever risk they ran in doing so.

The reader may think it curious that Zola should have expressed himself as a Positivist, and yet have harboured sundry petty superstitions, such as were enumerated in a previous chapter. That contradiction may well have proceeded from the duality of his nature, to which reference has been made more than once. However, in the novelist's later years the writer never observed any particular trace of the curious practices recorded by Dr. Toulouse. He had at least largely rid himself of them. The only sign he gave of arithmomania while he was in England was to count the women's hairpins which he saw littering the streets when he took his walks abroad; but he did that, he explained, to occupy his mind when he was alone and because he was struck by the vast number of hairpins which Englishwomen contrived to lose. Once or twice, too, in conversation he spoke of his luck, but people often do that without putting any particular faith in luck. In England he had certainly relinquished the practice of fingering things or setting them in particular positions before he left a room, and he gave no sign that he was haunted by any fear of death. Of that, on the occasions when he was ill, he spoke quite calmly, though in the spirit of a man who held that when one died it was for ever. At various times he had given some attention to spiritualism, but had found no little imposture in it, and nothing, said he, had convinced him of the survival of the individual soul.

Throughout the summer of 1902 he remained at Médan, correcting further proofs of "Vérité," and making a few preparations for "Justice," which was to have been the last of his "Évangiles." In August he wrote half a dozen times to Vizetelly respecting the translation of "Vérité" and its publication in England and America. Such business letters are of little interest, however, to the general public. It may just be mentioned that he said on one occasion, "Times are still very hard, but one consoles oneself by working"; the reference in this case being less to pecuniary matters than to his position in France generally, for he still remained under a cloud, as it were, in consequence of his participation in the Affair. In the early part of September he once more wrote to Vizetelly about "Vérité," and then came silence. At that moment, however, there was no occasion for further correspondence. So a few weeks passed, Vizetelly steadily proceeding with his translation of "Vérité" which had begun to appear in "Reynolds's Newspaper." But all at once, on September 29, telegrams from Paris startled the world with the news that Émile Zola had been found dead in his bedroom and that his wife had narrowly escaped dying with him. Circulation was also given to an absurd rumour that the case was one of suicide. On receipt of the news, Vizetelly, naturally enough, started for Paris.

On the previous day, Sunday, September 28, Zola and his wife had quitted Médan to take up their autumn and winter quarters at 21 bis Rue de Bruxelles, Paris, of which house they rented the ground and the first floors, the upper stories being tenanted by other persons, who by means of a communicating doorway came and went by the staircase of the adjoining house, in such wise that the Zolas were isolated from those who dwelt above them. Their chief apartment on the ground floor was a spacious dining-room, with a verandah whence one looked into a pleasant garden. Upstairs were two drawing-rooms, two principal bedrooms, a dressing and bath room, and the novelist's study, and in the winter all these apartments were warmed by hot air from an apparatus in the cellars. Naturally that apparatus had not been used during the summer, and thus the rooms were chilly when the Zolas returned from Médan. A fire was therefore lighted in their bedroom—with some difficulty, it would seem, for the chimney did not draw well. This chimney was common both to the Zolas' bedroom and to some apartments overhead, occupied by other tenants, one of whom had recently had it swept in its upper part. The sweeping, it is thought, may have brought down sundry fragments of brickwork and cement, which remained obstructing the lower part of the chimney, the Zolas on their side having given no orders for sweeping it, as, on account of the heating apparatus in the cellars, it was seldom used by them. In any case, whatever may have been the exact cause, the chimney was certainly obstructed, and on the evening of September 28 Madame Zola, observing that the fire burnt very badly, expressed an intention of having the chimney examined by some workmen who were engaged on various repairs in the rooms.

She and her husband sat down to dinner that evening about eight o'clock. They were very hungry and made a hearty meal. Then, at an early hour, being somewhat tired by their removal from the country to town, they retired to rest. At that moment Madame Zola observed that the bedroom fire was smouldering, and asked her husband if he wished it to be extinguished. He answered that he did not think it necessary, for it would soon burn out. Then one or the other lowered to within a few inches of the hearth the sheet-iron tablier, a kind of screen or shutter with which most French fireplaces are provided. They went to bed and fell asleep, but about three o'clock in the morning Madame Zola suddenly awoke, experiencing a feeling of great oppression. Her head was heavy and she was seized with nausea. She managed to get out of bed for the purpose of going to the adjoining dressing-room, but was no sooner on her feet than faintness came over her and she had to cling to the bedstead for support. At last she contrived to drag herself to the dressing-room, where she was able to breathe more freely. But the feeling of nausea persisted, and at last came violent vomiting, which kept her in the dressing-room for three quarters of an hour. This, however, helped to save her life, and feeling considerably relieved, she quitted the dressing-room and returned to bed. Her coming and going had wakened her husband, and after scolding a little pet dog which slept in the room on an arm-chair, from which it had climbed upon the bed, Madame Zola, thinking that she heard her husband complain, turned to him and inquired if he also felt unwell. "It is curious, but I do," he answered, explaining that his symptoms were akin to hers. She thereupon suggested that she should summon the servants, but he replied: "It is not worth while. We are both suffering from indigestion. It will be nothing, we shall be all right to-morrow." Then, intending to open a window or go to the dressing-room as his wife had done, he rose, looked for his slippers, and took a few steps. But all at once a fainting fit came upon him, and he was too far from the bedstead to use it as a support. His wife heard him gasp, then fall upon the floor. She called him, but he did not answer. She wished to go to his help, but again an oppressive stifling sensation suddenly came upon her and she was unable to rise or even press the electric bell in order to summon assistance. By a last despairing effort she managed to sit up in bed, but immediately fell back again, losing consciousness. That was all she was able to relate when she was subsequently questioned; she could remember nothing more.

At eight o'clock in the morning the two workmen who were making repairs in the house arrived, and Madame Monnier, the doorkeeper, set them on some quiet little jobs in order that her employers might not be disturbed. They, the Zolas, usually rose between eight and nine, but that morning time went by and they gave no sign of life. About nine o'clock Madame Monnier's husband, one of the two men-servants, knocked repeatedly at the bedroom door but obtained no answer. He and his wife then became alarmed, and with the help of one of the workmen burst the door open. To their horror and amazement they saw Zola lying in his nightgown on the floor, his feet just touching the rug beside the bed. One of the party at once opened a window, while Madame Monnier went to the bed where her mistress was lying unconscious. There was a second bedstead in the room, a small iron one, and to this some of the servants carried their master's body, then hurried in search of a doctor. The first to arrive was Dr. Marc Berman, a practitioner of Russian origin, who happened to be in a chemist's shop in the vicinity. He at once examined Zola and found no signs of life, though the body was still warm. Death had occurred little more than an hour previously, in all likelihood shortly after eight o'clock. Turning to Madame Zola, the doctor found her in an extremely weak state, but some hope of saving her remained, and indeed at the expiration of some twenty minutes the efforts to revive her to consciousness began to take effect, though they had to be continued for fully another hour.

Dr. Berman had sent to the chemist's for oxygen, ether, and an electrical battery; and in the hope that Zola might not be quite dead every possible effort to stimulate life was made. Artificial respiration, rhythmical tractoration of the tongue, injections of ether, frictions, the application of hot-water bottles, the electrisation of the diaphragm,—all the devices known to medical science were put into practice and persevered with for three hours by Dr. Berman and Drs. Lenormand and Main, who joined him. But nothing had any effect: Zola was indeed dead.[4]

Meantime telegrams were despatched to the novelist's intimate friends and his wife's relatives. The district Commissary of Police who had been summoned, communicated with the Prefect, and an official inquiry into the tragedy was at once ordered. Madame Laborde, a cousin of the Zolas, was soon on the spot, followed by M. Charpentier, M. Fasquelle, M. Desmoulin, and others; and late in the afternoon Madame Zola was removed to Dr. Defaut's Maison de Santé in the Avenue du Roule, Neuilly, in such wise that the investigations were pursued in all freedom. The bedroom chimney proved to be both defective and obstructed; and when a fire was lighted and some guinea-pigs were left in the room for a night, the animals, though still alive on the morrow, were then found in a hebetated state.[5] Meantime an examination of Zola's remains was made, the doctors afterwards reporting that all the vital organs were sound, though the blood was saturated with oxide of carbon.[6] This, it may be mentioned, fixes on the globules of the blood, whence it expels all oxygen, thereby producing drowsiness, numbness, and at last a species of paralysis. Perhaps in Zola's case the blood-poisoning may not have been the only cause of death, for it is possible that he might have survived in spite of it, if, like his wife, he had been able to relieve himself, and if he had not fallen on the floor of the room, where the atmosphere, impregnated with carbonic acid gas, may have been almost unbreathable. However, the experts virtually agreed in ascribing the death to the poisoning of the blood by carbonic oxide.

Madame Zola remained at Dr. Defaut's house for some days, regaining her strength very slowly. At first her husband's death was concealed from her, she believed that he was only ill like herself. But the sad truth had to be told, and then, after a violent explosion of grief, realising that she had duties to fulfil, she insisted on returning home in spite of her weakness. It was a terrible home-coming. Her husband's body had been embalmed with more or less success—for signs of decomposition had set in directly after the post-mortem examination—and laid in its coffin, which was placed in the study, where much of the novelist's work had been done. And it was there that the unhappy widow found it. But she gave proof of no little fortitude, and speedily signified her wishes and those which she knew to have been her husband's, in order that proper arrangements might be made in the dolorous circumstances which had now arisen.

The tragic character of Zola's death had created a sensation throughout the civilised world. Every day for an entire week the vestibule of the house in the Rue de Bruxelles was crowded with notabilities in literature, science, art, and politics, who came to inscribe their names in the registers. Telegrams, letters, and addresses of sympathy were continually arriving from all parts of France and from well-nigh every foreign country, emanating now from societies and associations, now from eminent men, now too from members of the French and foreign Governments. Wreaths and coronals and other combinations of flowers followed in profusion, and a public subscription was speedily started for a monument in Zola's honour. But the enemy did not disarm. Vile libels were sold on the boulevards. Henri Rochefort wrote a foul article in "L'Intransigeant," insinuating that Zola had committed suicide because he had discovered Dreyfus to be really guilty. Édouard Drumont declared in "La Libre Parole" that the name of Zola inspired horror in all who possessed French hearts. "La Patrie" shrieked that the dead man had defended treason and vilified the flag. The renegade Jews of "Le Gaulois," after asserting that he had shown no pity for France, declared, "Nevertheless we are Christians, and we therefore hope that God will show some mercy to this wretched creature who knew no compassion." The said Jews, by the way, after the usual fashion of renegades, had never evinced the slightest pity for the martyr of Devil's Island, but in their Catholic fervour had fiendishly approved of the abominable tortures devised by the Under Secretary for the Colonies, the strangely named Lebon. As for "La Croix," the organ of the religious orders, it viewed Zola's death with unctuous complacency, admitting that the occurrence might well have been "a merciful accident by which at least one crime had been spared that wretched man." But another clerical rag, calling itself "Le Peuple Français," declared with all solemnity that God had stifled Zola in punishment for his sins. Others enlarged on that theme: it was by no mere coincidence, they said, that Zola had died on Michaelmas Day, St. Michael had really descended in the Rue de Bruxelles! Thus Paris was again divided into two hostile camps, Dreyfusites and anti-Dreyfusites confronting one another threateningly as if the Affair had sprung to life again from Zola's ashes.

There had been great changes, however, in government circles. An insidious malady having compelled M. Waldeck-Rousseau to resign office after carrying the policy of Republican defence no further than its first stage, the prime ministership had passed to M. Combes, a man then very much misunderstood by most people, who ascribed to him a vacillating character, whereas his friends were aware that he really possessed a remarkably strong will, and that if he now and again seemed to follow rather than direct the course of events this was mere diplomacy on the part of one who never lost sight of the goal he desired to attain. M. Combes and his colleagues were undoubtedly on the side of truth and justice, and though, in the state of public opinion, they felt they could not appeal to the Legislature to accord a national funeral to Zola's remains, they at once decided that the Government should participate in the obsequies.

Zola's will, a very brief one, executed in 1883 and bequeathing all his property to his wife, contained no indication of where or how he desired to be buried. But the widow was well acquainted with his desires, and gave instructions that the interment should take place in Paris and, as in Hugo's case, without any religious rites. The question was raised whether an application should be made to the authorities for the military honours to which Zola was entitled as an officer of the Legion of Honour, his suspension from which had ceased with the Amnesty. It was decided to make no such application, but to accept the honours if they were tendered, which decision was scarcely taken when the Minister of War, General André, signified his resolve that they should be accorded. He further sent his chef de cabinet, General Percin, to the Rue de Bruxelles to tender his condolences, whereupon the Nationalist newspapers began to shriek that the army was disgraced. As it was also asserted by a writer of "Le Gaulois," a renegade Jew named Pollonnais, that General Percin, having met ex-Captain Dreyfus at the house, had shaken hands with him, Count Boniface de Castellane, the notorious husband of a daughter of Jay Gould, wrote to General Percin inquiring if this were true. The contemptuous answer which ensued led to a duel in which each combatant slightly wounded the other. As a matter of fact, General Percin had not met M. Dreyfus when he called in the Rue de Bruxelles, and had therefore had no occasion either to offer or refuse him his hand.

The victim of the military and clerical factions had naturally been admitted to view the remains of the man who had so ably championed his cause, and it was also natural that he should desire to attend the funeral. But every effort was now being made to rouse anti-Semitic passions, and Madame Zola dreaded lest the interment should be disturbed by some horrible riot. She therefore begged M. Dreyfus to refrain from attending, pointing out to him that the police authorities, like herself, were of opinion that his presence would give rise to great disturbances. M. Dreyfus was deeply affected by the request; he regarded his attendance at the obsequies as a matter of duty to his defender, and felt that everybody would accuse him of cowardice should he hide himself away. At last Madame Zola's entreaties prevailed, and he consented to do as she desired. The reports of this interview which appeared in the newspapers checked the Nationalist outcry, and on the eve of the funeral, when it had been ascertained that the authorities had decided to take every possible precaution to preserve order, it was felt that the decision with respect to M. Dreyfus might be altered. He was therefore informed that he might attend, and he gladly availed himself of the permission.

The obsequies were celebrated on Sunday, October 5, in the presence of a vast concourse of people. The distance from the Rue de Bruxelles to the place of interment, the Montmartre cemetery, was fortunately short, and to keep the crowd in check the Place Moncey and the Boulevard de Clichy were lined with police and municipal guards. Two squadrons of cavalry were also kept in readiness, though virtually out of sight, one assembling on the Place Vintimille, within a stone's-throw of the Rue de Bruxelles. Access to that street was afforded only to the bearers of special "laissez-passers," the numerous deputations assembling in neighboring thoroughfares and joining the procession on the road. In front of the house in the Rue de Bruxelles a detachment of the Twenty-eighth Infantry of the Line was mustered, under the command of Captain Olivier, an officer who had always believed in the innocence of Dreyfus, and who after refusing to participate in a subscription in honour of the forger Henry had fought a duel with one of the latter's partisans. Three cars bearing a profusion of wreaths, many extremely large,—splendid chrysanthemums of various hues being the predominant flowers,—preceded the hearse, on which a few other wreaths were placed. The drums beat and the soldiers presented arms when the coffin was brought from the house, escorted by the pall-bearers and followed by relatives and intimate friends. The pall-bearers were MM. Ludovic Halévy and Abel Hermant, respectively Presidents of the Société des Auteurs Dramatiques and the Société des Gens de Lettres, MM. Charpentier and Fasquelle, Zola's publishers, M. Théodore Duret, the historian, M. Alfred Bruneau, the composer, M. Octave Mirbeau, the novelist and playwright, who had held Zola's power of attorney during his exile in England, and M. Briat, the secretary of the Labour Exchange. Immediately behind the hearse walked MM. Laborde and Loiseau, relatives of the deceased, M. Fernand Desmoulin and Dr. Larat, intimate friends, followed by M. Anatole France and a few others. Then came Dr. Le Prince and Vizetelly, between whom, with his hands in theirs, was little Jacques.... The representatives of the Government followed. All the state departments were represented, and M. Chaumié, Minister of Public Instruction, attended in person. Then, after a crowd of celebrities in literature, science, art, politics, and law, came innumerable deputations, many of them carrying wreaths and coronals, a cortège of fifty thousand persons, advancing amid the concourse of spectators whom the military and police held back. The order was perfect, all heads were uncovered, all voices stilled. As the hearse passed on, the police saluted, the military presented arms. Again, inside the cemetery, on either hand, all along the Avenue St. Charles, and the Avenue de Montmorency, men of the Garde Républicaine stood at attention and presented arms until the cortège at last halted on an open space, where a tribune had been erected for the funeral orations.

The first address was delivered by M. Chaumié, who began by speaking of the terribly sudden death of the departed author, which had sent a thrill of stupefaction through the world. From all quarters, both at home and abroad, there had come messages of condolence, and the Government of the Republic had made it a point of honour to be represented at the obsequies. As others would speak of Zola's literary genius, he (the Minister) would refer more particularly to the mission which the deceased had set himself,—that of painting so striking a picture of society, with its sufferings, its passions, and its vices, that even those with the poorest sight would perceive that remedial measures were imperatively needed. Whenever a cause had seemed to him just he had espoused it without hesitation, braving all furious or perfidious anger, the wildest insults, the most unjust hatred, the most painful betrayals. And thus the humble and the wretched, feeling that they had lost a great friend, were now mingling their gratitude and their grief with the admiration of those who deplored the immense loss which had befallen literature.

It was particularly from the literary standpoint that M. Abel Hermant next addressed the throng, and he did so admirably, setting forth both the characteristics and the limitations of the genius of Zola, who had perhaps failed to show sufficient penetration when dealing with the psychology of certain individual characters, but who had excelled in depicting what was called "the crowd." He had been a master in the art of assembling facts and personages: his crowds and his paintings of nature were full of life. And he had never sought common popularity. He had sacrificed nothing in order to curry favour with the multitude, as was done by those who were eager for success at any price. Far from flattering the masses, he had braved them, measured himself against them fearlessly, and not only in connection with the terrible truths enunciated in his novels had a clamour of anger and menace arisen around him. At last, passing to his peroration,—a very appropriate one,—M. Hermant said:

"At the close of one of his finest works[7] Zola describes a ceremony such as this, one unattended by a great concourse of people, but none the less painful for the few friends pressing around the remains of an unappreciated artist. On retiring from the graveside one of that artist's most notable companions, one who resembles Zola like a brother,[8] speaks a few words,—words of duty, comfort, and hope. Those words are certainly the only farewell that Zola himself desires from us, gentlemen, and I should feel I had failed in giving expression to one of his last desires, did I leave this spot without repeating those words to you. I certainly did not think that the duty would come so soon, nor did I think it would be for me to lend my humble voice to my master in order to remind the multitude around me of the humble yet magnificent device of his whole life: 'Let us work!'"

Only discreet marks of approval had attended M. Chaumié's speech. Now, however, for the first time in the day's proceedings, a burst of applause rang out. But M. Hermant had quitted the tribune, and in his place appeared M. Anatole France, who came to bid Zola farewell on behalf of all his friends. M. France had testified for him at the Paris Assizes, he had supported the cause of truth and justice from the outset, and moreover, now that Zola was gone, his own eminent position in literature seemed all the greater. Thus, from every standpoint, it was well that he should have been selected to say the last words. He spoke as follows:

"Gentlemen,—In rendering to Émile Zola on behalf of his friends the honours which are due to him I will say nothing of my grief and theirs. Those who leave great names should not be celebrated by lamentations, but by manly praise and a sincere picturing of their life and work. The literary work of Zola was immense.... When one saw that work arising, stone by stone, its immensity caused surprise. Some admired, some were astonished, some praised, some blamed it. Praise and blame were bestowed with equal vehemence. The great writer was occasionally assailed—I know it by my own example—with reproaches which were sincere and yet unjust. Invectives and apologies intermingled, and still and ever the work grew. Now that one can contemplate the whole of its colossal structure the spirit pervading it may also be discerned. It was a spirit of kindliness. Zola had a kindly nature. The candour and the simplicity of great souls were his. He pictured vice with a rough and virtuous hand. His seeming pessimism, the sombre humour cast over more than one of his pages, scarcely conceals his real optimism, his stubborn faith in the advance of human intelligence and knowledge. In his novels, those social studies, he pursued with vigorous hatred an idle and frivolous society, a base and baleful aristocracy; he fought against the evil of the age,—the power of money. Though a democrat, he never flattered the multitude, he strove to show it what slavery proceeds from ignorance, what dangers come from strong drink, which delivers it over, senseless and defenceless, to every form of oppression, every kind of wretchedness, every sort of shame. He fought against social evils wherever he met them. They were the things he hated. But in his last books he showed the whole of his love for mankind. He strove to divine, to foresee, a better social state. He desired that an ever increasing number of the human race might be called to happiness in the world. He set his hopes on the human mind, on science. He awaited from new powers of machinery the progressive enfranchisement of toiling humanity. A sincere realist, he was nevertheless an ardent idealist. In grandeur his work can only be compared to that of Tolstoï. At the two extremities of European thought the lyre has raised two vast ideal cities. Both are generous and pacific; but whereas Tolstoï's is the city of resignation, Zola's is the city of work.

"While he was still young, Zola acquired fame. In quietude and celebrity he was enjoying the fruits of his labour when he suddenly wrested himself from all repose, from the work which he loved, from the peaceful pleasures of his life. Doubtless, in presence of a coffin only grave and serene words should be spoken, calmness and harmony should be preserved. But you are aware, gentlemen, that calmness is found only in justice, that repose is found only in truth. I speak not of philosophical truth, the subject of our endless discussions, but of that moral truth which we can all detect because it is relative, sensible, in conformity with our nature, and so near to us that a child can touch it with the hand. I will not fail, then, in my duty to justice which orders me to praise that which is praiseworthy. I will not hide the truth beneath cowardly silence. Why, indeed, should we be silent? Are they, his slanderers, silent? I will say only what is necessary before this bier, but I will say all that is necessary."

At this point M. Anatole France paused, interrupted by repeated cries of "Bravo!" Those who were gathered around the tribune had listened in attentive silence to the earlier part of his discourse, but from this point almost every sentence was punctuated by applause. The crowd in the cemetery was so dense, stretching away to the very gates, that thousands were unable to hear a word of the speech, and the "Bravos!" which rang out from those who were more fortunately placed, naturally excited the others, whom the police restrained with considerable difficulty. Meantime M. Anatole France was continuing:

"Having to recall the struggle upon which Zola entered in the cause of truth and justice, is it possible for me to preserve silence respecting those who were bent on ruining the cause of an innocent man, those who felt that if he should be saved, they would be lost, and who with all the desperate audacity of fear therefore strove to overwhelm him. How can I remove them from your gaze when I have to show you Zola rising, weak and unarmed, before them? Can I remain silent about their lies? That would mean silence as to his heroic rectitude. Can I remain silent about their crimes? That would mean silence as to his virtues. Can I remain silent about the outrages and slanders with which they pursued him? That would mean silence as to his reward and honours. Can I remain silent about their shame? That would mean silence as to his glory. No! I will speak out.

"With the calmness and firmness which the spectacle of death imparts, I will recall the dim days when egotism and fear had their seats in the government councils. People were beginning to know something of the iniquity, but it was supported, defended, by such public and secret powers that the most resolute hesitated. Those whose duty it was to speak out remained silent. Some of the best, who feared nothing personally, dreaded lest they should involve their party in frightful dangers. Led astray by monstrous lies, excited by odious declamation, the multitude of the people, believing they were betrayed, grew exasperated.... The darkness thickened. Sinister silence reigned. And it was then that Zola addressed to the President of the Republic that well-measured yet terrible letter which denounced falsity and collusion.

"With what fury was he assailed by the criminals, by their interested defenders, by their involuntary accomplices, by coalitions of all the reactionary parties, by the deceived multitude, you know that full well. You saw innocently minded people joining in all simplicity the hideous cortège of hireling brawlers. You heard the howls of rage and the cries of death whioh pursued him even into the Palais de Justice during that long trial when he was judged in voluntary ignorance, on false testimony, amid the clatter of swords. I see here some of those who then stood beside him, who shared his dangers. Let them say if ever more insult was hurled at a just man! Let them say too with what firmness he endured it! Let them say if his robust kindliness, his manly pity, ever deserted him, if his constancy was for a moment shaken! In those abominable days more than one good citizen despaired of the salvation of the country, of the moral fortune of France. Not only were the Republicans defending the present régime terrified, but one of the most resolute enemies of the régime, an irreconcilable Socialist, exclaimed bitterly, 'If present-day society be so corrupt as this, one will not even be able to found a new society on its fragments!' Indeed, justice, honour, common sense, all seemed lost.

"But all was saved. Zola had not merely revealed a judicial error, he had denounced the conspiracy of all the forces of violence and oppression leagued together to slay social justice, Republicanism, freedom of thought in France. His courageous words awoke the country. The consequences of his deed are incalculable. They unroll themselves to-day in power and majesty, they spread out indefinitely, they have determined a movement of social equity which will not stop. A new order of things is arising, based on a better sense of justice, on a deeper knowledge of the rights of all.

"Gentlemen, there is only one country in the world where such great things could have been accomplished. How beautiful is the genius of our fatherland! How beautiful is that soul of France which in past centuries taught equity to Europe and the world! France is the land of ornate reason and kindly thoughts, the land of equitable magistrates and humane philosophers, the land of Turgot, of Montesquieu, of Voltaire, of Malesherbes. And Zola deserved well of the country by refusing to despair of justice in France. We must not pity him for having endured and suffered. Let us rather envy him! Set above the most prodigious heap of outrages ever raised by folly, ignorance, and malice, his glory attains to inaccessible heights. Let us envy him: he honoured his country and the world by immense literary work and by a great deed. Let us envy him: his destiny and his heart gave him the grandest fate: in him at one moment was set the conscience of mankind!"