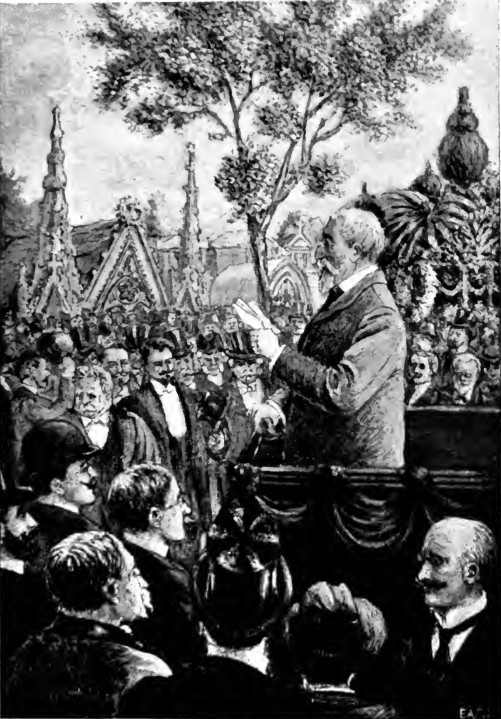

M. Anatole France delivering his oration at the funeral of Émile Zola

The presence of death, all around one in that great cemetery, was quite forgotten when M. Anatole France ceased speaking. Tumultuous applause arose while relatives and friends were taking up their positions for the march past of the thousands attending the obsequies. Several ladies, Mesdames Laborde, Charpentier, Fasquelle, and others,[9] had joined the family party, which stood in line on the verge of a transverse avenue, immediately in front of the tomb of the famous Baron Hirsch. For two hours the march past continued. M. Dreyfus, accompanied by M. Gabriel Monod of the Institute of France, and M. Lalance, a former Alsatian deputy, passed unrecognised by the great majority. But Maître Labori and Colonel Picquart were acclaimed. A host of distinguished men went by, and after them came all the deputations, the town of Denain sending a pitman, a blacksmith, and a peasant, each attired in the costume of his calling,—the first with his "Davy," the second with his leather apron, the third shouldering his scythe. In a like spirit Freemasons wore their insignia, and again and again came wreaths of flowers and "immortelles," silver palms and other tributes, borne in procession as far as the provisional vault. Every now and then, moreover, some deputation halted for a moment before the hearse, and cries were raised of "Glory to Zola! Honour to the apostle of justice!" Others called, "Germinal! Germinal!" in memory of Zola's great book in which he had taken the part of the toilers against the greed of the capitalists. For the rest, the crowd was most orderly, and one was struck by the presence of an immense number of young men about twenty years of age, the electors and artisans of the future, with whom perhaps some day the great principles laid down by Zola may finally triumph. Not until the vast concourse had gone onward, one hundred and fifty persons passing every minute, did the hearse proceed to the temporary vault to which Zola's remains were quietly committed. There were a few disturbances outside the cemetery, where several parties of anti-Semites had now assembled, but these were speedily quelled by the police and the municipal guards. And thus the long ceremony, which had lasted some four hours, came to an end.

For several months, however, the great novelist's widow continued to receive tributes of sympathy. The municipalities of various towns bestowed the name of Rue or Boulevard Zola on one and another thoroughfare, thus testifying to the revulsion of feeling in favour of Dreyfus's champion. A considerable sum was yielded by the subscription[10] for a public monument to be erected in some part of Paris, perhaps the Tuileries garden, and a design for this monument was commissioned. In February, 1903, the novelist's last book "Vérité" was published.[11] Then in March the greater part of his library was sold at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris, some twenty-six hundred volumes being thus dispersed.[12] There was a curious illuminated manuscript breviary of the fourteenth century which Zola had used while writing "Le Rêve," and numerous historical, philosophical, medical, and other scientific works, with some volumes of voyages and travels, and collections of periodicals. None of the above, the breviary excepted, were of much value, but considerable interest attached to a very large collection of presentation copies of modern novels and stories, including all those of Guy de Maupassant and many by the Goncourts, Gustave Flaubert, Alphonse Daudet, Paul Bourget, Halévy, Huysmans, Marcel Prévost, Anatole France, Claretie, and others. All those works were inscribed to Zola by their authors. In a copy of Flaubert's "Tentation de St. Antoine" were written the words, "à Zola un solide que j'aime"; while the "Trois Contes" contained the inscription "à Émile Zola, bon bougre! et du talent! son vieux, Gve. Flaubert." Some interest attached also to M. Waldeck-Rousseau's "Questions Sociales," published in 1900, for it was inscribed "à Émile Zola en témoignage d'admiration"—and yet M. Waldeck-Rousseau was the statesman who in that same year carried the Amnesty Law against which Zola so strongly protested! From this little circumstance one can divine what were M. Waldeck-Rousseau's private sentiments, whatever may have been his public declarations with respect to the Affair. The books sold at the Hôtel Drouot comprised also many of the translations of Zola's novels in different foreign languages, and the sale further included a variety of tapestry, curios, and works of art. The total proceeds were about six thousand one hundred pounds. It may be added that more than eight hundred of the inscribed presentation volumes were purchased by Mr. James Carleton Young, a well-known American book-collector, of Minneapolis, who proposes to establish in that city a magnificent library, in which every work will bear an inscription by its author. Autograph letters and manuscripts are also to be included in the collection, which already comprises several thousand volumes by dead and living writers in virtually all languages.[13]

It remains to be added here that on May 26, 1903, in the presence of a few relatives and friends, Zola's remains were quietly translated from their provisional resting-place to a tomb—designed by M. Frantz-Jourdain—facing the rond-point or open space near the entrance of the Montmartre cemetery There they will probably remain until the French nation decrees their removal to the Pantheon.

[1] See ante, p. 430.

[2] "Travail," Paris, Fasquelle, 1901, 18mo, 666 pages; some copies on special papers, etc. Seventy-seventh thousand in 1903.

[3] In the early parts of this year, 1902, Messrs. Raoul de Saint-Arroman and Charles Hugot produced a dramatic version of "La Terre" which attracted considerable attention. Some scenes were certainly interesting, but the play was deficient in cohesion. The same authors had previously adapted "Au Bonheur des Dames" for the stage. Subsequent to Zola's death M. de Saint-Arroman related in "Le Siècle" that on being asked what percentage of the author's rights in those plays should be paid to him the novelist had answered, "Whatever you like." Zola's enemies often insinuated that his nature was a grasping one in money as in other matters, but there was no truth whatever in the charge.

[4] The pet dog which had slept in the bedroom was in a very weak state, but it had vomited during the night, and this may have helped to save it. Another little dog which had remained in the dressing-room had not been ill.

[5] The statement current in some newspapers at the time that the fire which had such a fatal result was of artificial fuel such as compressed coal dust was inaccurate. Coal was employed, and the writer believes it to have been Welsh anthracite, for Zola bought such coal in considerable quantities, chiefly for the electric light installation at Médan, whither it was brought up the Seine by barge from Rouen. That such coal would not burn well in a defective chimney is certain. It ignites with difficulty unless there be a good current of air. On the other hand, it throws out little if any smoke, and it is a significant circumstance that none was found in the bedroom.

[6] The writer was in the house while the post-mortem examination was made, and to the best of his knowledge and belief it lasted about forty minutes. In view of the stifling fits induced by a form of angina from which Zola had suffered periodically ever since 1875, it was strange to hear that all the organs were sound. It is not for the writer to engage in any discussion with medical men, but he cannot reconcile their report with the complaint from which Zola undoubtedly suffered.

[7] "L'Œuvre."

[8] Sandoz.

[9] Madame Zola was not present, her relatives and friends having entreated her to remain at home.

[10] The writer believes that the subscription still remains open (March 1904), the amount received not being quite sufficient for a monument on the scale which the committee has in view. The treasurer is M. Lucien Fontaine, 1 Rue Jacob, Paris. The committee is a representative one of distinguished Frenchmen.

[11] "Vérité," Paris, Fasquelle, 18mo, 749 pages. Presentation copies and those of the first thousand with a mourning border on their covers.

[12] It is certain that the fortune left by Zola was of very moderate amount, for he had never hoarded money. Besides the large sums he had expended in connection with the Dreyfus case, he had for many years discharged a number of family obligations with respect to relatives in modest circumstances both in Italy and France. He was also the providence of the poorer peasantry around Médan, and the number of struggling young writers whom he helped with his purse was large.

[13] Mr. Young has acquired some scores of letters written by Zola, notably several bearing on his attempts to gain admission to the French Academy.

The tragic elements in Zola's life—His place in history—Consequences of his action in the Dreyfus case—Survival of his novels—His influence on other writers—Social influence of some of his books—Zola's apostolic fervour—His prophetic instinct—"Germinal," "Travail," "Paris," and the French masses—Zola's unwritten book "Justice"—Result of his denunciations of vice—Immorality in Paris—Drunkenness in France—Why Zola should be remembered.

Such was the life, such also the death, of the greatest fighter that France produced in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The foregoing narrative, whatever may be its imperfections, will at least have given the reader some idea of that strenuous career which from youth onward was one long battle, an incessant expenditure of will, energy, and talent. It was also, like a battle, a resounding career, most of whose phases echoed all around. In the time of Alexandre Dumas père it used to be said, "When Dumas sneezes, all Paris starts"; and the same might have been subsequently said of Zola, some of whose "sneezes," indeed, reverberated far beyond Paris or even France. Looking at his life from another standpoint it will be found akin to a tragedy in several respects,—not the kind of tragedy which suggests thoughts of blood, thunder, and thrilling horrors, but one of hidden suffering and unrealised aspirations. That may be regarded perhaps as a petty, commonplace sort of tragedy, such as is enacted here and there every day, and left unrecorded. In Zola's case we see aspirations, efforts, struggles, disappointments, domestic trouble, misrepresentation, insult, and hatred, ending in death by accident, with just a few years of popularity and wealth thrown in to deepen, by force of contrast, the shadows of the rest. Even if we regard Zola's tragedy as that of a man's fight for the benefit of his fellowmen against those men themselves—and such it largely was—most of its features will be found to be of a familiar kind. One often perceives heroes and heroines, enthusiastic workers, fighters, and thinkers, who think not like the herd, who strive solely for that which they themselves deem to be right. Few achieve their purpose; the majority fail, disappear, die—as often as not—broken-hearted. Yet with a new generation others always arise to renew the combat. Now and again one of these enthusiasts secures a modicum of success, attains perhaps a hundredth part of his ambition, effects a hundredth part of the good he has dreamt of, leaves among many suggestions a single useful one behind him. But though the success of each individual worker may be very slight, that which he accomplishes is not lost; joined to what is accomplished by other workers, it enlarges the sum of progress. Each additional grain of wheat means an increase of the harvest, and of those who bring that grain to the store it may be said that even if they have failed in nine tenths of their efforts their failure is only relative.

In Zola's career, as in the careers of most men, there was both failure and success. Near as he still is to us, it is difficult to tell how far his measure of success will be permanent, how far his work and memory will survive him. We believe that by his action in the Dreyfus case he carved for himself an imperishable niche in the history of his country. Assuredly no historian, whatever his school, whatever his opinions, will be able to omit Zola's name from any record of the Third French Republic, for, as M. Anatole France said at his graveside, the consequences of Zola's action in the Affair have been immense. Far-reaching changes in the internal policy of France have proceeded from his deed, which led to a disclosure of the real sentiments of those Clericalists and Militarists who were closing in upon the Republic to destroy it. For a time the issue seemed doubtful; but the policy of Republican defence was inaugurated by M. Waldeck-Rousseau and has proceeded and expanded under his successor, M. Combes. To Zola and his letter "J'Accuse," and to the letter's various consequences, many of the events which have occurred in France since 1898 may be easily traced, even by those who know nothing of the novelist's political friendships, of his private intercourse with statesmen who during the Dreyfus turmoil lacked either the opportunity or the energy to intervene, and who, while privately assuring Zola of their sympathy, their conviction even that he was right, repeated to him: "Unfortunately I am not in office and I am therefore powerless. Besides, though I see the danger which you point out, it is very difficult to deal with. One must act with extreme prudence, for the patriotism of the electorate is aroused, and the Republic might be wrecked by precipitate action." Subsequently, after the death of Félix Faure, who was too deeply committed to the military party to take any honest, impartial action, some of the men who had held such language as one has indicated came to the front again, and then, as they gradually took confidence, things slowly changed. When the secret history of the Dreyfus affair from the political standpoint comes to be written, there will doubtless be more than one curious disclosure in which Zola will figure.

We take it, then, that he is assured of a niche in French history. The question of the ultimate survival of his novels is more difficult to determine. He himself declared on one occasion, in a public speech, that it was great honour for a literary man if he were only for one moment the spokesman of his generation and were even fated to oblivion afterward. Of course he, like other writers, aspired to some future fame. At any rate, even as he will figure in national history in connection with the Affair, so must his novels figure—and figure prominently, we think—in literary history. Can one imagine any record of the literary movement in the latter half of the nineteenth century containing no mention of Zola's writings? Independently of the writings themselves account has to be taken of their influence on other authors, not merely in France, but virtually all the world over. Zola always disclaimed any intention of founding a literary school. He protested repeatedly against such a suggestion. He had imitators certainly; all prominent writers have. But apart from those who deliberately set themselves to copy his methods, there were others, more independent, who in one or another respect yielded to his influence. Something of the Naturalism of the Rougon-Macquart series at least found its way into the English novel, in which also there came a reflection of Zola's later manner. Mr. George Moore may deny that he sprang from Zola, and may claim direct descent, as Zola did, from Flaubert and others. But in any case the principles on which Mr. Moore has often worked have been the same as those which Zola adopted. Nearer to Zola in some respects was the late Mr. George Gissing, who in others suggested Maupassant. The late Mr. Frank Norris, the American novelist, was manifestly influenced by Zola's later works; and it seems at least likely that various books by Mr. Hall Caine and Miss Marie Corelli would never have been written if Zola had not raised certain problems in such volumes as "Lourdes" and "Rome." Of Mr. Thomas Hardy it may be said perhaps, as of Mr. George Moore, that he has at least occasionally worked on lines running parallel to those on which Zola worked for years. It would be possible also to enumerate a large number of instances in which Zola's liberating influence has clearly appeared, even when his actual methods have not been followed. One may claim for him that he contributed largely and powerfully to free the modern novel from many shackles, with a result which is conspicuous on all sides. That nothing but Naturalism should remain in fiction as the result of his theories and efforts, was of course out of the question. Zola himself admitted that he had been a mere sectarian when in a dogmatic moment he had once suggested it. But certainly he helped to sweep away many conventionalities, and encourage an accurate presentment of life. Fiction, or at least that branch of it which claims to portray real life, is no longer the same as it was before he arose, and it seems hardly likely that it will ever revert to its former state.

With respect to the actual survival of his books as current literature, that, we think, will depend almost as much on circumstances as on their merits. They are not light reading. He himself was well aware of it, and, as we know, he said of himself, the Goncourts, and others, that future generations might well find their works difficult to read. Many already find it difficult to read Balzac, though he possessed a gift of humour which was lacking in Zola. On the other hand, Zola's style was generally much superior to Balzac's, though the latter was a good grammarian and could write admirable straightforward French when he pleased, as witness many letters in his "Correspondence." In the case both of Balzac and of Zola some knowledge of French history, politics, manners, and other matters is necessary for a proper understanding of their works. "Les Rougon-Macquart," like "La Comédie Humaine," can only be fully appreciated by those who are familiar with the period it treats of; and though Zola usually confined himself to the elemental passions which are also the eternal ones, it is perhaps doubtful whether works of fiction which tax the reader's knowledge in many ways can hope for immortality. Yet possibly the Rougon-Macquart series has a better chance of survival than is possessed by some of Zola's other books, whose social influence has been greater. Influence of that kind has certainly been exercised by some of the Rougon-Macquart volumes, though not in the same degree as by such great machines de guerre as "Lourdes" and "Rome," which reinforced by "Vérité" have proved factors of weight in the great struggle between clericalism and free thought in France. As engines of warfare for use in that struggle, they may survive for many years; but the struggle ceasing they would probably be soon forgotten, as is usually the case with books whose purpose is too ostensible. That example will explain the meaning of our remark that the survival of many of Zola's works will depend on circumstances. In the final triumph of the principles which his last and unfinished series enunciated, we feel considerable confidence. We believe, as Zola did, that the whole world is tending slowly but surely to better things, that we shall come at last to a more natural and more upright life, that increase of knowledge will bring increase of truth, increase of equity, and that the day will come when science will at last confound all superstitions.

One of the men for whom the novelist in his latest years testified the most respect was M. Berthelot, the eminent scientist, long the friend of Renan. It says much for M. Berthelot that he should have exercised considerable influence on two such men, but it should be remembered that if they differed in many ways they also had their points of contact. Though Zola was no priest, whereas Renan remained one in some essential respects until the end, he had in him an apostolic fervour which many a priest might have envied. Even in the days of the Rougon-Macquart novels, which were so impersonal, that fervour displayed itself freely in all Zola's miscellaneous papers, his literary, theatrical, and art criticisms. And it is somewhat remarkable that with this strong fervour within him he should so long have contrived to check and subdue it directly he turned from an essay to a novel. When he ceased to do so and allowed it to invade his novels, the cry of "a new Zola!" arose among those whose knowledge of his writings was confined to his earlier fiction.

Besides his apostolic fervour, Zola, like Renan, possessed a kind of prophetic instinct, which proceeded from the exercise to which he constantly subjected his brain. Every time when in preparing a new novel he had assembled a number of facts, he proceeded to draw deductions from them, to weigh all probabilities and possibilities; and his mind being thus trained, dealt in the same way with all the current events in which he took interest. During his year's stay in England at the time of the Dreyfus case he repeatedly told the writer that he felt sure so-and-so would happen, and in nine cases out of ten his predictions were accurate. At times when the writer went to him with a preconceived opinion or some forecast taken from a newspaper it was particularly interesting to hear him analyse it, examine it under every aspect, and confirm or refute it in accordance with his view of the probabilities. On such occasions his systematical and logical mind was fully revealed; and one may say that the prescience which he often displayed was far more a matter of knowledge and logic than of inspiration. The latter undoubtedly came to his aid on some notable occasions, but even when he so fervently declared his belief in the innocence of Captain Dreyfus—at a time when all positive proof thereof seemed lacking—he at least had some logical basis for his belief which his expertness in deduction had intensified.[1]

It has been pointed out that several of Zola's later books influenced the community, or at least a large section of it, in connection notably with the struggle between Church and State in France. "Germinal" and "Travail," which circulated widely among the working classes, must also have exercised considerable influence. Of recent years the latter work has frequently furnished subjects for lectures delivered to working-class audiences in the French provinces as well as in Paris; and although, as was remarked in a previous chapter, "Travail" may not be in some respects a very practical work, its pacific tendencies are admirable, and the worker who comes under their influence can but reject the more violent courses which some leaders of advanced opinions have preached. Again, "Paris," which is not held to be one of Zola's greatest books, has met with no little favour among the masses, less because it paints the corruption existing in some spheres of society than because it gives voice to the chief demand of the masses, which is for justice. It does not treat the subject fully, being more concerned with the failure of charity to cope with the necessities of the modern world, but it indicates that justice should take charity's place, and this accords so well with the feeling of the multitude that the favour accorded to the book is but natural.

If Zola had lived another year he would have dealt exhaustively with that subject of social justice,—equity between class and class, man and man. It was to have been treated in the last volume of his "Évangiles." Only two days before his death, on the eve of his return from Médan to Paris, he wrote to his publisher, M. Fasquelle, that on the following Monday morning he should begin to prepare that concluding work. He was unable to do so, for on the morning stated he died; and foul-minded bigots, on hearing of his intention, repeated with a sneer, "He was going to begin 'Justice'—well, justice has been done to him." But whatever vileness may have come from men who ever had the words "We are Christians" on the tip of their tongues or at the point of their pens, all those who are in any degree oppressed may well regret that the hand of death robbed them of a powerful statement of their rights.[2]

It would not appear that the flagellation of vice which one finds in the Rougon-Macquart novels has had any widespread effect in France, though it has undoubtedly done good in individual cases. From the general standpoint Paris shows little sign of improvement in some matters. The number of illegitimate births and the number of divorce cases remain extremely large. It may be said, however, that these point less to absolute immorality than to new conceptions of marriage and discontent with existing laws. With respect to the illegitimate births one finds the fathers of the children constantly recognising their paternity in the official declarations of birth, and thereby making themselves responsible for the upbringing of the little ones. The fact is that cohabitation without marriage seems to increase, while there is a falling off both in the number of marriages and in the cases of desertion following seduction.

As regards "L'Assommoir," respecting which the writer has often cordially re-echoed the opinion that it is one of the greatest temperance tracts ever written, one can only say that, like other books of Zola's, it has done good in individual instances, but has failed to stem the general passion for strong drink. The sobriety of the French nation was at one time almost proverbial, but there has been a great change in that matter since the War of 1870. The efforts of various kinds made to check the consumption of alcohol in Paris itself have in a measure proved successful, the average having been reduced during recent years from nine to seven quarts per annum per head of the population. But Normandy tells a terrible tale: At Caen the consumption is fifteen quarts per head, at Rouen it is over sixteen, at Havre it is seventeen, and at Cherbourg, eighteen. It is not surprising, therefore, to find that the depopulation of Normandy is proceeding apace, that the women, who are as much addicted to drink as the men, can seldom bear children, and that even when they become mothers they are unable to suckle their babes. Thus one of the sturdiest races of France is perishing, destroyed by cider and potato spirit. The very children often drink on their way to school, insanity flourishes, and immorality is widespread.[3]

But reforms are not accomplished in a day; and in many instances authors may write in vain, even as the clergy may preach, if legislation does not come to their aid. In some matters even legislation is futile, and then reform can only come gradually, as the result of example and knowledge. To improve the nation you must usually begin by improving the individual. If, then, Zola succeeded in his aims in individual cases—and the writer holds strongly that he did—he effected all that he could reasonably hope for. He did not stamp out vice in France. Neither has the State done so, nor has the Church, nor has any other powerful and wealthy organisation. Zola had only his brain and his pen, and with those weapons he did his best, according to his lights. He was all sincerity; hypocrisy was the thing he most detested. He fought the good fight. After setting forth the evil that was, he preached the cleanly and the fruitful life, brotherliness, equity, rectitude, and truthfulness. He desired the suppression of all noxious agents, and it was because he regarded the Roman Church as such that he assailed it so fiercely. Moreover, he did not share the delusion which imagines a heaven beyond the skies; he wished to set a heaven in this our planet. That was his ideal. He did not believe in resignation. He placed his faith in work and effort. He loved his Mother Earth, he pictured her beauties. He loved his fellowmen; in his harshest moments he sought their good only. The one error of his life showed how human he was. If he were ambitious it was that he might advocate the principles in which he believed, with more and more authority. In a dim and dolorous hour,

"when God himself seemed dumb

And all his arching skies were in eclipse,"

this abused and insulted novelist turned from his work and smote for truth and justice. Others shall decide whether he was a man of genius; suffice it for us that, all his life, he was a man of bravery. He feared none. If there was tragedy in his career, he knew how to bear it. He felt, he prophesied, the day would come when justice would be done to him. That day is hastening; and in whatever estimation his writings may be held hereafter, whether some survive, whether all sink into oblivion, his memory will assuredly abide for many generations, for the world does not willingly forget those who teach it courage,—the first, the foremost quality that life demands of man.

[1] As the result of constant exercise, his mind often worked with great rapidity in these matters, the various aspects of a case and its possibilities coming to him almost in a flash.

[2] Zola left behind him the libretto of a drame lyrique, "L'Enfant Roi," which M. Bruneau has since set to music, and which is to be performed at the Opéra Comique in Paris.

[3] In the autumn of 1902 the writer was a guest at one of the monthly dinners of the French Society of Anthropology. Several members had lately returned from Normandy where they had been making exhaustive inquiries into the subject referred to above. The consensus of opinion was that the drink curse had caused greater ravages in Normandy than in any other part of Europe.

The year 1840, this fourth day of April, at a quarter past two o'clock in the afternoon, before us, Barthélémy Benoist Decau, knight of the Legion of Honour, Mayor of the Third Arrondissement of Paris, discharging the functions of registrar of births, deaths, and marriages, there has appeared the Sieur François Antoine Joseph Marie Zola, civil engineer, forty-four years of age, residing in Paris at No. 10 bis Rue St. Joseph, who has presented to us a child of the male sex, born the day before yesterday, at eleven o'clock in the evening, at the appearer's residence, being the son of the said appearer and of Françoise Émilie Aubert, his wife, married in Paris at the municipal offices of the First Arrondissement, on March 16, 1839; to which said child the appearer has given the forenames of Émile Édouard Charles Antoine. Entered in the presence of Norbert Lecerf, grocer, age fifty-two years, residing in Paris, at No. 18 Rue St. Joseph, and of Louis Étienne Auguste Aubert, of independent means, age fifty-six years, residing in Paris at No. 106 Rue de Cléry, maternal grandfather of the said child. And after perusal of the present the father and the witnesses have signed, ZOLA, LECERF, AUBERT, DECAU, mayor.

The year 1902, this thirtieth day of September, before us, Mayor of the Ninth Arrondissement of Paris, declaration has been made of the death of Monsieur Émile Zola, officer of the Legion of Honour, homme de lettres, who died the twenty-ninth September in Paris, at his residence, situated No. 21 bis Rue de Bruxelles, at the age of sixty-two years. Son of the deceased François Zola, engineer, and of the deceased Émilie Aubert. Husband of Madame Alexandrine Gabrielle Zola, née Meley. In testimony of which the declaring witnesses have signed with us, LABORI, M. DUTARD, mayor.

Some information respecting the first editions, etc., of Zola's writings has been given in a number of foot-notes in the course of the present volume. That information is by no means exhaustive, but pending the appearance of a complete bibliography, which will surely be undertaken before long, it may be acceptable to various readers and book-collectors. For the convenience of those who are unacquainted with French, the author here appends a list of the translations in the English language which are known to him. Unfortunately he has no acquaintance with the great majority of those issued in America. Should the present volume be reprinted, and information concerning American translations be supplied to him through his publisher, he will endeavour to include it in a future edition. He may mention now that he believes several translations of merit have been made in the United States by Mr. Benjamin R. Tucker.

With respect to the English translations those published by Vizetelly & Co. between 1884 and 1889 were the following: "The Fortune of the Rougons," "The Rush for the Spoil" ("La Curée"), "A Love Episode" ("Une Page d'Amour"), "Fat and Thin" ("Ventre de Paris"), "The Conquest of Plassans," "Abbé Mouret's Transgression," "His Excellency E. Rougon," "The Assommoir," "Nana," "Piping-Hot" ("Pot-Bouille"), "The Ladies' Paradise" ("Au Bonheur des Dames"), "How Jolly Life is!" ("La Joie de Vivre"), "Germinal," "His Masterpiece" ("L'Œuvre"), "The Soil" ("La Terre"), "Madeleine Férat," "Thérèse Raquin," and "A Soldier's Honour" (short stories). All the above were issued in crown octavo form. There were also large octavo editions of "Nana," "The Assommoir," and "Piping-Hot," each with about one hundred illustrations. The smaller volumes also contained illustrations or frontispieces. After the first proceedings at law against the publishers, most of the above translations were re-expurgated and reissued. The reissues were distinguished from the earlier editions by the words "A new Edition," and by the heading "The Rougon-Macquart Family," I, II, III, etc., which heading does not appear on the title-pages of the first and fuller editions. There was, however, no such reissue of "Nana," "Piping-Hot," and "The Soil." In some early catalogues "Claude's Confession" was announced by the firm, but the writer does not find that it was ever published. The above translations are all out of print, with the exception of "The Soil," which is sold in France only by the proprietor of the copyright of that translation (Paris, Flammarion). In consequence of the conviction of Henry Vizetelly it may not be sold in the British dominions.

The English translations now in circulation in Great Britain are enumerated below. Here and there in the list the writer has mentioned some American editions known to him. In the case of the Rougon-Macquart series the order in which the volumes are placed is that in which they should be read.

ROUGON-MACQUART SERIES.

I. "The Fortune of the Rougons," edited with an introduction by Ernest A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto and Windus, St. Martin's Lane.

II. "His Excellency" ("Son Exc. E. Rougon"), edited, etc., by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto. The same, published in New York by the Macmillan Co.

"La Curée" should follow here, but there is no English version on sale.

III. "Money" ("L'Argent"), translated by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto.

IV. "The Dream" ("Le Rêve"), translated by Eliza E. Chase. Eight illustrations. London, Chatto.

V. "The Conquest of Plassans," edited, etc., by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto.

"Pot-Bouille" should follow here, but no English version is in circulation.

VI. "The Ladies' Paradise" ("Au Bonheur des Dames"), edited, etc., by E. A. Vizetelly. Frontispiece. London, Hutchinson & Co., Paternoster Row.

VII. "Abbé Mouret's Transgression," edited, etc., by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto.

VIII. "A Love Episode" ("Une Page d'Amour"), translated by E. A. Vizetelly. Ninety-four illustrations. London, Hutchinson.

IX. "The Fat and the Thin" ("Le Ventre de Paris"), translated by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto.

X. "The Joy of Life," edited, etc., by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto.

XI. "The Dram Shop" ("L'Assommoir"), edited, etc., by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto.

XII. "His Masterpiece" ("L'Œuvre"), edited, etc., by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto.

XIII. "The Monomaniac" ("La Bête Humaine"), translated by Edward Vizetelly (see ante, p. 248, foot-note). London, Hutchinson.

XIV. "Germinal," edited by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto.

"Nana" should follow here, but no English version of the slightest value is in circulation, though of this and a few other volumes there are some paltry adaptations, which omit from a third to half of those works as they stand in the original French.

After "Nana" should come "La Terre," no English version of which is sold in Great Britain.

XV. "The Downfall" ("La Débâcle"), translated by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto.

An American translation, under the same title, by E. P. Robins, was published by the Cassell Co., New York, 1893. The Macmillan Co. also catalogues a translation, perhaps the same.

XVI. "Doctor Pascal," translated by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto.

An American translation by Mary J. Serrano is published by the Macmillan Co., New York.

The "TROIS VILLES" series: I, "Lourdes," II, "Rome," and III, "Paris," as translated by Ernest A. Vizetelly, is published in London by Chatto and Windus, in New York by the Macmillan Co.

Of Zola's last series, "LES QUATRE ÉVANGILES," only three volumes were issued, the translations being as follows:

I. "Fruitfulness" ("Fécondité"), translated by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto; New York, Doubleday.

II. "Work" ("Travail"), translated by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto.

An American translation called "Labor" is issued by Messrs. Harper, New York.

III. "Truth" ("Vérité"), translated by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto; New York, John Lane.

There are also the following translations of Zola's miscellaneous novels and short stories:——

I. "Thérèse Raquin," translated by Edward Vizetelly, London, Grant Richards.

II. "A Dead Woman's Wish" ("Le Vœu d'une Morte"), translated by Count C. S. de Soissons. London, Greening.

III. "The Mysteries of Marseilles," translated by Edward Vizetelly. London, Hutchinson.

IV. "The Honour of the Army and other Stories" ("Le Capitaine Burle," "Naïs Micoulin," "Nantas," etc.), edited by E. A. Vizetelly. London, Chatto. This volume is not identical with the one called "A Soldier's Honour," formerly published by Vizetelly & Co., some of the tales contained in the latter having been omitted, and others added.

V. "Stories for Ninon" ("Contes à Ninon" and "Nouveaux Contes à Ninon"), translated by Edward Vizetelly. 2 vols. London, Heinemann.

VI. "The Attack on the Mill," etc. London, Heinemann.

One may also mention Zola's "Letters to France" (Dreyfus case), introduction by L. F. Austin. London and New York, John Lane.