Samira ElAtia

University of Alberta, Campus Saint-Jean

In January 2005, I joined the English Language Program (ELP) at the University of Alberta as a research fellow working on language tests. Dr. Grazyna Pawlikowska-Smith had retired as the director of the ELP, so I never had the chance to meet her. However, I had the chance to get to know her fantastic work at the English Language Program, and of course her tremendous contribution to the original Canadian Language Benchmarks (CLB) – the 2000 edition (Pawlikowska-Smith 2000).

Prior to joining the University of Alberta and the ELP, I worked mainly with the guidelines of the American Council for the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL). As a language teacher, I received my training from Alice Omaggio-Hadley, who was a past president of ACTFL, and was well known for her work in language program development and language teaching around the ACTFL guidelines (Omaggio-Hadley 1993, 2001). In the summer of 2001, I even attended the examiner’s training workshop for the ACTFL Oral Proficiency Interviews. During this time, the CLB were not well known beyond certain groups in Canada, let alone abroad.

As I worked with the CLB at ELP from 2005 on, I became more and more aware of their empirical value, of their clearly stated descriptors, and more important, of the fluidity of the materials developed to assist in their implementation. I appreciated their value for language program development: the CLB are straightforward, clear, precise, and among the very first language descriptors to use the Can Do Statements from a learner’s perspective as part of their breaking down of the language competence components and constructs targeted at each level. It was during my tenure as the chair of the Task Force on Language Standards for the International Language Testing Association from 2007 to 2009 that I studied the CLB in depth. I did several critical comparative analyses of the ACTFL and the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) scales. To me, the CLB are pioneers, for they are specific to adult language competence within the Canadian context.

By 2008, when I attended the annual gathering of the International Language Testing Association, Language Testing Research Colloquium (LTRC) in China, several Canadian colleagues were presenting their assessment work anchored in the CLB, with a focus on language training and assessment for nursing, the CELBAN (namely the work of David Watt at the University of Calgary; see Watt and Lake 2000). With a strong contingent of Canadian specialists in language assessment, and with the CLB as a reference to use in assessment, we held our first meeting at that time to start formal talks about establishing a Canadian Association for Language Assessment.1 At this time, the CLB had an international and national presence, with several academics and researchers using the CLB as framework for their work.

Last year, when I presented at the International Conference on Language Learning and Culture in Fairfax, Virginia (ElAtia 2015), I was surprised by how many American and overseas academics were familiar with the Benchmarks,2 were speaking highly of them, and were referring to them for their research and program development. They were impressed by the updated edition of the CLB, as well as the uniquely developed Niveaux de compétence linguistique canadiens (NCLC).

Indeed, when in 2009 the Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks (CCLB) decided to update the NCLC, they formed a team of specialists who spoke French, worked in French, and were aware of the French situation and nuances in Canada. They selected specialists who were knowledgeable of the legal and judicial situation of French, as well as the historical and political implications and realities of French in minority situations, in French immersion programs, and in bilingual contexts, as well as in unilingual Francophone contexts. The adaptation process that the NCLC underwent is a testament to how developing language programs in two languages should be done. Instead of going for a translation of the English CLB to French, the NCLC were adapted and developed separately. French and English are two different languages that require different ways of teaching because of their nature, their cultural place in Canadian history, and their uses and mandates in Canada. The International Testing Commission (2011), in its twenty-two guidelines, emphasized the importance of the adaptation, and warned about the cultural and pragmatic components of a language that are not taken into consideration when translating (ElAtia 2011).

The CCLB is a national not-for-profit organization established in 1998, funded by the Canadian government, and “governed by a nationally representative, multi-stakeholder board of directors, including representation from government, ESL and FSL experts, and language assessors” (CCLB website 2016: www.language.ca).

The vision and mission statements of the Centre are stated as follows:

Vision

The Canadian Language Benchmarks and the Niveaux de compétence linguistique canadiens are the national standards recognized in Canada and internationally for describing, measuring and recognizing English and French language proficiency of immigrants and prospective immigrants destined for Canada.

Mission

The Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks/Centre des niveaux de compétence linguistique canadiens leads and provides expertise in the implementation and dissemination of the Canadian Language Benchmarks and the Niveaux de compétence linguistique canadiens as practical, fair and reliable national standards of English and French language proficiency, in educational, training, community and workplace settings. (CCLB website 2016)

In the statement above, the last sentence articulates very clearly the scope of the Benchmarks. In line with this mission statement, the Centre strongly warns against the use of the Benchmarks outside of their intended context without valid research backing up such use. However, since the Benchmarks have been developed by world-renowned specialists through a rigorous process, with a focus on adult language learners, the CCLB has the necessary expertise to offer guidelines and directives to all individuals and institutions in and outside of Canada that would like to use the Benchmarks as a reference.

Performance descriptors (or guidelines) are statements of expected ability and/or competence in a language (ElAtia 2011). As such, the Benchmarks:

1. Serve as guidelines for curriculum design in language teaching, as scales for establishing item difficulty and establishing language constructs, and as criteria to be achieved at different levels of both teaching and assessment, and they serve as the genesis of language test tasks and items.

2. Serve in determining a person’s proficiency in a language independent of any language learning program. These include a person who is not learning the language at the moment, or has not learned the language in a conventional academic way, but would like to know his or her proficiency level. Performance descriptors are not exclusively for educational needs, as they serve many other purposes, such as work, immigration, promotion, and/or personal interest (in knowing one’s competence level in a language).

3. Serve test developers as language performance descriptors – test developers may refer to descriptors when constructing tests and when analyzing and making inferences about results.3

In short, the Benchmarks provide “a national framework of reference for the development of language learning programs, curricula and materials relevant to the needs of adult newcomers to Canada during the process of settlement and integration” (CCLB website 2016) for both official languages, French and English. They are used for “describing, measuring and recognizing the second language proficiency of adult immigrants and prospective immigrants for living and working in Canada” (CCLB website 2016).

The Benchmarks are composed of twelve levels divided into three proficiency stages – basic, intermediate, and advanced – covering the four classic language skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing (see Table 6.1 below). In this regard, they are on a par with other state-of-the-art competency descriptors (see ElAtia 2011 for comparison between the CLB, the ACTFL, and the CEFR).

Table 6.1. Breakdown of Stages and Levels in CLB

| Stage I | Stage II | Stage III |

| Basic proficiency Benchmarks 1 to 4 | Intermediate proficiency Benchmarks 5 to 8 | Advanced proficiency Benchmarks 9 to 12 |

The Benchmarks are context-specific. They serve distinct purposes in Canadian society, where French and English are the two official languages within a multicultural setting that allows all Canadians to maintain their cultures and their own native languages, be they Urdu, German, Mandarin, Cree, or any another language.

Among other researchers, Saville (2009, 26) stresses the need for “understanding test purposes and related contexts”; otherwise, several issues would arise from clashes between policy and decision makers on the one hand, and testing practitioners and examinees on the other hand. Hence, in a situation where a language test would be chosen by Canadian immigration officials to assess the language competence of adult immigrants, the Benchmarks should logically be selected as a point of reference for this test. If decision makers favour another set of competence descriptors, such as, for instance, the CEFR, and use a test that is calibrated using those levels, unfairness and validity threaten to hang over the decision-making process. Strong arguments need to be made to justify such a choice, since the Benchmarks already exist, developed in Canada, by a Canadian agency, to serve this very purpose of assessment. It would be questionable to use anything else that does not address the mandate and context of the particular Canadian testing situation. As an example of this good practice, in England and in the Netherlands, when officials were deciding on language assessment tools for immigration and citizenship purposes, the CEFR was selected without hesitation for establishing the appropriate level of competence, since both countries adhere to the Convention of Europe that mandates the use of the CEFR as a way to standardize language competence descriptors across Europe (Blackledge 2009, De Jong et al. 2009).

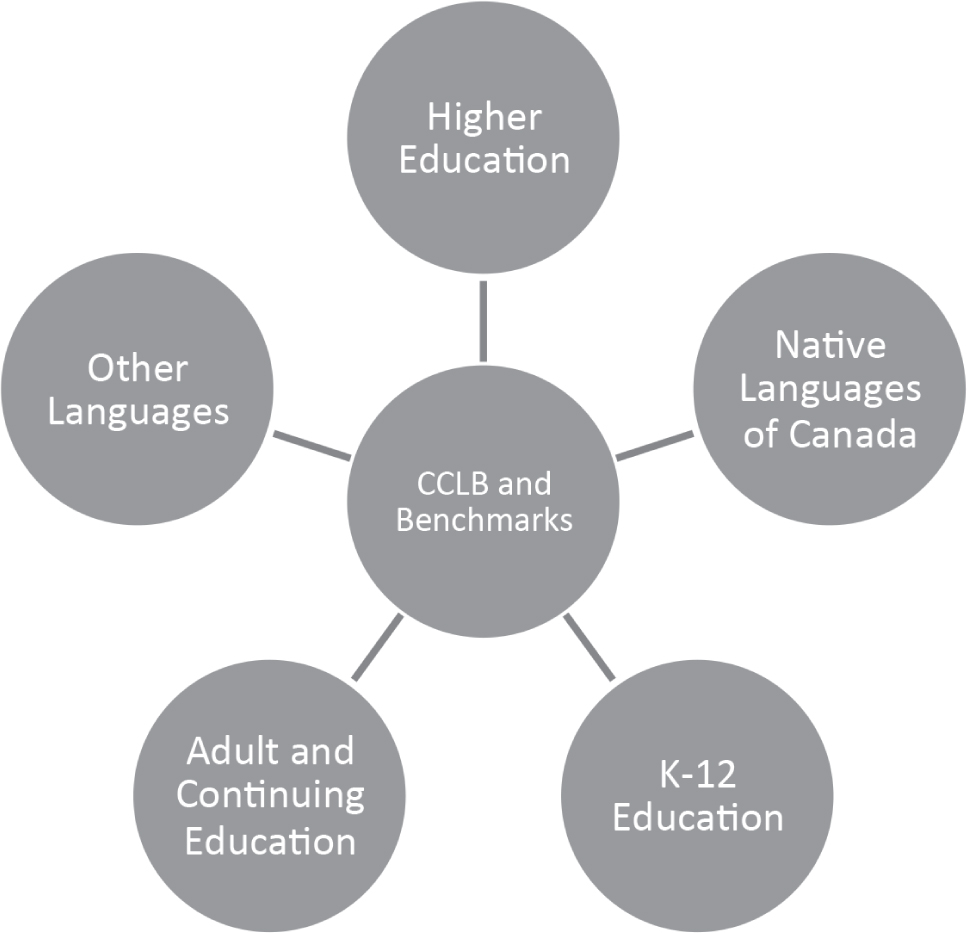

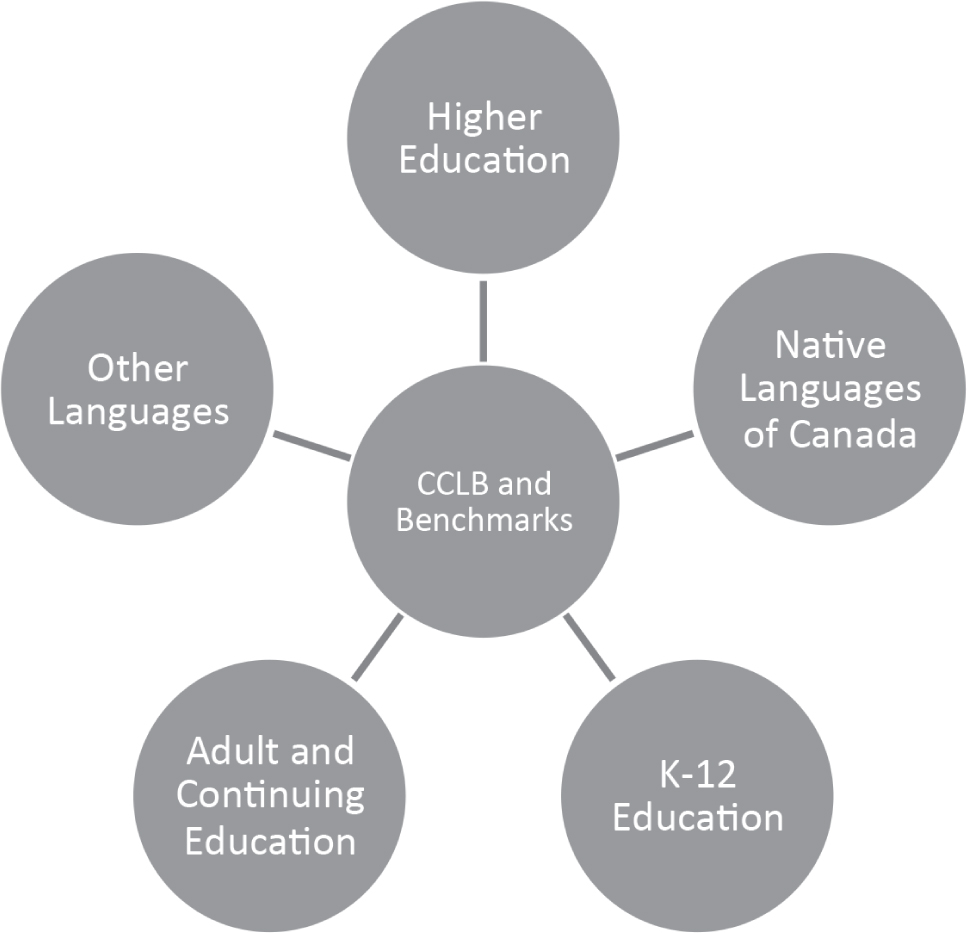

Because of their broad scope, the Benchmarks can play a major role in advancing research on language learning, language assessment, and language program development. In my opinion, the national and international future of both the Benchmarks and the CCLB lies in research. Indeed, for the first almost twenty years, the CCLB solidified its place within Canada as a leading agency for language program development and language learning and assessment. The coming years should be focused on branching out from the traditional portfolio and touching other populations and contexts where it can have an important impact. This will only materialize if solid diverse research is conducted on the Benchmarks. For this to happen, the CCLB would have to play a pivotal role. In the following sections of this paper, I elaborate on the chart below to outline the various contexts and potential research subjects connected with the Benchmarks, besides the clientele intended for the present time, that is, foreigners coming to work in Canada and adult immigrants settling in Canada.

Figure 6.1. CCLB and the Benchmarks: various potential areas of research

In higher education, the use of the Benchmarks has become an urgent issue. There are three groups that could benefit greatly from research on the Canadian framework: international students, registrar offices, and language program developers.

According to Saif (2013), international students make up a large and growing category. The majority of these students already fulfil, to some degree, the language requirements of their respective institutions. Others come to Canadian post-secondary institutions exclusively to learn English (or French), or to learn English (or French) as a prerequisite to another, more specialized or content-oriented, degree. In both these cases, the students are young adults who have completed grade 12, and hence the use of the Benchmarks would apply to them. Moreover, as mentioned earlier and demonstrated in various chapters of this book, the Benchmarks match other competency descriptors at the content level, they are meant for adult language education, and they target second-language speakers. Finally, they have been developed by Canadian experts for Canadian education and contexts. And yet, in higher-education language programs, in language progress assessment, and in admission criteria for language competence, they are not used.

The Benchmarks would offer registrar officers and language program administrators a springboard to work from for placement, as well as for their program development and specification. They offer a solid platform of support to all those who use the related materials for assessment (diagnostic and placement), as well as for formative assessment, achievement, and most important, for competency assessment. The Milestones high-stakes test, described in chapter 3 of this book, holds great promise for language assessment in Canada. Research on the Milestones, as well as other batteries of assessments and tests developed by the CCLB, needs to be instigated from a variety of angles: course requirements, backwash, and content/construct validity – all within the framework of higher-education contexts. For this reason, the Milestones scores should also be considered as a Canadian alternative to the IELTS, TOEFL, CAEL, or other test scores that provide a snapshot about potential students’ language proficiency.

The resources developed by the CCLB, described in chapters 3 and 4 of this book, offer a great support to the teachers and to language program developers. For instance, the materials developed for CELBAN, described in the chapter 4, demonstrate an excellent application to the Canadian context. Using this resource, one can therefore attest that students are able to function and to work in a Canadian reality once they finish their degrees. And yet again, such materials have been shunned by post-secondary institutions, except for some small programs. As a case in point, in my home institution, the University of Alberta, the ELP, the TESL, and the Faculty of Nursing are the only ones fully versed in and fully aware of the Benchmarks and the materials that the CCLB offers to supplement them.

Research on the applications of the Benchmarks in academic contexts is still lacking, and for their range of uses to improve, much work needs to be done. However, for this research to occur, and especially in order to determine funding, there needs to be a willingness on the part of the various stakeholders, both federally and provincially: the institutions of higher education and the provincial ministries of higher education, as well as various institutions of the federal government. For initial steps, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) may be very helpful, since international students have undergone the process for their visa and temporary residency status before joining their universities. Among the topics that need researching in the academic context are the following:

1. Language training for international students who are at the graduate level or working as teaching or research assistants. These students account for a large portion of the international students in Canada. Some of them, those who come in as immigrants or skilled workers, do receive thorough training via programs that are Benchmarks-based, but the rest do not. This needs to be studied to establish the feasibility, validity, and accountability of such programs.

2. While the CLB are well anchored, the NCLC are much less so. As the fourth chapter of this book shows, the diverse, varied, and complex situations for Francophone education and French as a minority language programs for adults are much more precarious and need more investment. So far, Canadian institutions of higher education seek the tools and resources coming out of France to evaluate students and to develop programs. Moreover, they use indicators, books, materials, and tests developed in the United States. AlHamid and ElAtias’s (2016) study regarding the stereotypes that students form concerning the variations of French in Western Canada is alarming: a majority of students who studied in French viewed the Metropolitan variety from France as superior to the Canadian one (Laurentian) because most of the materials come from France. Since the realities for French programs in Canadian higher education are very particular, they need to be studied within a unique cultural lens, such as the one proposed in the NCLC and related materials.

3. French immersion and Francophone stream programs should look closely at the products that accompany the NCLC (for instance, the self-assessment tools and the language portfolio assessment) for local solutions to local challenges. In fact, at the present date, assumptions about the level of language competence among students in these programs are diverse and sometimes contradictory, which poses challenges to admissions officers. Articulation committees in both British Columbia and Alberta, as well as the Language Consortia, are currently involved in intense discussions about the level of language competency in both French and English for students who finish high school and who register for university.

If there is one place where the CLB has blossomed, it has been in the field of adult education. Within Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), formerly Human Resources Canada, there are at least two categories where the Benchmarks should be recognized and used: foreign workers and literacy/essential-skills development. In both, research is needed for implementation, for feasibility of validity, and fairness.

Within the requirements of many jobs in Canada, the parameters for language proficiency are set for foreign workers. When establishing scores/setting standards for the specific jobs that target foreign workers, the common practice has been to refer to the guidelines established by IRCC. However, ESDC (2016) also states provisions for language that affect foreign workers, such as:

Language restriction provision

A distinct language assessment provision has been introduced as subsection 203 (1.01) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations. As a result, English and French are the only languages that can be identified as a job requirement both in job applications and in job advertisements by employers, unless they can demonstrate that another language is essential for the job.

Language proficiency provision for caregivers

Employers must ensure that the caregiver being hired speaks, reads, and understands at least one of Canada’s official languages (English or French). Caregivers must have a level of fluency that enables them to communicate effectively and independently in an unsupervised setting.

When setting up the parameters for language requirements, some organizations do already refer to the CLB as indicators of language proficiency (see chapter 4 for more details), but much research still needs to be done with regard to setting standards for specific jobs – research that would include various stakeholders from hiring agencies, governing bodies, and associations of certain jobs and trades, as well as representatives from the CCLB. These stakeholders would make better-informed decisions that are fair and valid. In addition, research needs to be conducted for diagnostic and formative assessment after the foreign workers start their work, in order to longitudinally study the development of official-language skills among this group.

Among the major work that ESDC oversees is the literacy and essential-skills portfolio. According to ESDC, literacy and essential skills are needed for work, learning, and life; are the foundation for learning all other skills; and help people evolve with their jobs and adapt to workplace change.

Essential skills, and more particularly literacy, are of interest to many stakeholders across Canada. They are important indicators of the well-being of the active population in Canada, and can be revealing about the state of education, as well as the economic and social status of Canadians (including rates of poverty and crime). Essential skills:

include the skills associated with literacy (i.e. reading, writing, document use and numeracy) but go beyond to also include thinking skills, oral communication, computer use/digital skills, working with others and the skills associated with continuous learning. They provide the foundation for learning all other skills and enable people to better prepare for, get and keep a job, and adapt and succeed at work. (ESDC website 2016)

In his 2012 report, Harwood refers to data gathered by Statistics Canada from the International Adult Literacy Survey to draw attention to the alarmingly weak level of literacy skills (reading, writing, oral communication) of thousands of Canadians who finished high school but have not attained the base levels of literacy they need. Harwood (2012, 3) reported that a level-3 literacy skill on the IALS (on a scale of 5) is the average level needed to fully function in Canadian society, “yet 43% of all students leaving Canada’s high schools still do so with Level 1 and 2 skills.”

One could strongly advocate researching the use of the CLB and the NCLC in the literacy domain. They are developed in a way that targets language competence within a holistic literacy framework. To advance a national dialogue about improving the essential skills for an important part of the adult population, the use of nationally developed guidelines would be ideal: it would provide a platform that all stakeholders could agree upon. Again, the future outlook of the Benchmarks and the potential use for adult Canadians is great.

Besides French and English, other languages spoken, taught, and used in Canada could benefit from the expertise of the CCLB. With the Multiculturalism Act (Government of Canada 1988), languages of immigrants can be taught in schools. For these languages, which include Ukrainian, Spanish, German, Arabic, Urdu, and Tagalog, there are no standards for competency descriptions or for program development. They may not benefit from an official status like French and English, but school boards and communities do offer language-program support. Since it is left up to boards and local programs to develop and assess the language-learning process, the CCLB could play a guiding role in developing specific benchmarks for these languages. It is much needed and a number of stakeholders would benefit from it.

The goal of this chapter is to share possibilities for expanding the national and international role that the CCLB can play with regard to language education. Twenty years after its creation, and with two versions of the CLB, and the NCLC, as well as the batteries of materials for supporting professional language education, the Centre has anchored itself as a leading agency in the field. It has built strong roots in excellence on many levels and on many layers. As a member of the board of directors, I came to appreciate the CCLB and the outstanding work it carries. The research opportunities are abundant across Canada, in every one of the fields I have mentioned above. However, to move forward to the next twenty years, serious discussions need to be carried out among stakeholders, both provincially and federally. Many institutions and agencies, namely CMEC, IRCC, the tri-council, provincial ministers of education, and higher education, need to unite behind a great intellectual Canadian product that has been developed by scholars from across Canada to serve Canada.

AlHamid, Sofyan, and Samira ElAtia. 2016. “La diversité de la langue française en milieu académique : des représentations linguistiques aux enjeux sociolinguistiques.” Journée du savoir de l’ACFAS.

Blackledge, Adrian. 2009. “As a Country We Do Expect: The Further Extension of Language Testing Regimes in the United Kingdom.” Language Assessment Quarterly 6:6–16.

De Jong, John, Matthew Lennig, Anne Kerkhoff, and Petra Poelmans. 2009. “Development of a Test of Spoken Dutch for Prospective Immigrants.” Language Assessment Quarterly 6:41–60.

ElAtia, Samira. 2011. “Choosing Language Competence Descriptors for Language Assessment: Validity and Fairness Issues.” Synergies Europe 6:165–175.

_____. 2012. “A Minority within a Minority: Challenges and Implications for New Francophone Immigrants Learning English.” Embracing Challenges: Proceeding of the 11th METU International ELT Convention, 78–92.

_____. 2015. “Assessing Across the Disciplines: Online Formative Assessment in Bilingual Education.” Next Generation Assessment Conference. Fairfax, Virginia.

Employment and Social Development Canada. 2016. Program requirements. Accessed March 10, 2016. www.esdc.gc.ca/en/foreign_workers/hire/caregiver/requirements.page

Government of Canada. 1988. Canadian Multiculturalism Act. Ottawa: S.R.C. 24 (4e suppl.). Accessed December 20, 2015. http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/C-18.7.pdf.

Harwood, Chris. 2012. State of Literacy and Essential Skills Field. Ottawa: Canadian Literacy and Learning Network.

Omaggio-Hadley, Alice. 1993. “Research in language learning: Principles, processes, and prospects.” ACTFL Foreign Language Education Series 24:96–123. Lincolnwood, I.L.: National Textbook.

_____. 2001. Teaching Language in Context, 3rd ed. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Pawlikowska-Smith, Grazyna. 2000. Canadian Language Benchmarks 2000: English as a Second Langauge for Adults. Ottawa: Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks.

Saif, Shahrzad. 2013. “The language proficiency of international teaching assistants in Canadian universities: training, assessment, and screening.” Canadian Association of Applied Linguistics Annual Conference. University of Victoria, Canada.

Saville, Nick. 2009. Language Assessment in the Management of International Migration: A Framework for Considering the Issues. Language Assessment Quarterly 6:17–29.

Watt, David L., and Deidre M. Lake. 2000. Canadian Language Benchmarks-TOEFL research project: A comparison study of the Canadian Language Benchmarks assessment and the test of English as a foreign language. Research report. Accessed March 10, 2016. http://files.eric.ed.gov.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/fulltext/ED456665.pdf.

1 Present at LTRC 2008 were Shahrzad Saif from Laval University, Janna Fox from Carlton University, Samira ElAtia from the University of Alberta, David Watt from the University of Calgary, Eunice Jung from the University of Toronto, Liying Cheng from the Queen’s University, and Carolyn Turner from McGill University.

2 Instead of using CLB/NCLC throughout the document, I will be using “Benchmarks” to refer to both.

3 Around the world, many sets of competence descriptors are being developed, but for almost a decade now, the CEFR has dominated the field. Other examples of competence descriptors are the ACTFL guidelines widely used in the 1980s and 1990s, and the CLB. In this chapter, the CLB and the ACTFL are used as a point of comparison to the CEFR.