Chapter 2

The Salvadoran Model of 1948–1972

A Paradigmatic Failure

On 2 April 1944, while the dictator was out of the capital, a coup d’etat was staged against Martínez. The movement was suppressed with considerable violence, but a general strike and strong pressures from the United States persuaded Martínez to resign on 8 May. Martínez named a sixty-two-year-old general, Andrés I. Menéndez, to serve as interim president. With the support of progressive elements clustered around Arturo Romero, Menéndez appointed a fairly representative cabinet and issued a call for elections. He also allowed labor to organize, and the National Workers Union (UNT) quickly grew to about fifty thousand affiliates by October. Assisted by Agustín Alfaro Morán, Romero organized the Partido Unión Democrática (PUD), and after a brief absence to undergo surgery in the United States, Romero began to campaign vigorously for the presidency. The other main contender was General Salvador Castañeda Castro, a former minister of the interior during the Martínez era, who counted on the support of most of the military who opposed a return to civilian rule and of the landowners who were adamantly opposed to Romero’s reformist platform.

As the government of Arturo Araujo had done earlier, the junta of General Menéndez was embarked on an attempt to bring about a peaceful process of transition to a democratic regime in El Salvador, and under very difficult circumstances. Economic conditions were more favorable in 1944, but that was not the problem. The basic obstacle that this attempt could not overcome was the obstructionism of the military and the oligarchy, who for different reasons would not tolerate the inauguration of a democratic regime. The military was reluctant to allow a return to civilian supremacy, while the oligarchy perceived a democratic regime, which would allow the rise of other institutions and interests, including true political parties and labor unions, as a direct threat to its economic predominance.

Lacking the unequivocal support of the military the Menéndez junta could do little to prevent the violence directed against the campaign of Romero and his PUD. On 30 June 1944 the military high command forced Menéndez to postpone the August election and to name Colonel Osmín Aguirre, an architect of the massacre of 1932, as his chief of police. This diluted the already feeble control that the government had over the security forces. Moreover, aperturista elements could not count on the PUD, which was only an embryonic political organization. Lacking an experienced cadre to maintain discipline and perform the indispensable work of building up a viable organization at the grass-roots level, the party was incapable of well-coordinated action.

On 20 October 1944 the attacks against Romero culminated in a violent incident. About ten thousand romeristas were marching to their party headquarters after holding a rally at the Parque de la Libertad in San Salvador. Marching past the headquarters of Castañeda, they were fired upon. As though acting on cue, Aguirre reacted by incarcerating hundreds of romeristas, as well as the entire cabinet. Menéndez was forced to resign, and the members of the legislature were assembled at the Zapote barracks to witness the swearing in of Aguirre as provisional president. He immediately cracked down on the opposition, driving most of the romerista leadership out of the country and conducting a very thorough repression against the UNT. In December he crushed a revolt in San Miguelito and beat back an invasion launched by the opposition from Guatemala. Aguirre went through with the election, but he made sure that Castaneda Castro’s victory was all but certain. The new president was inaugurated on 5 March 1945.1

During the 1940s three factions were clearly discernible in the Salvadoran armed forces. One consisted of senior officers of the Martínez generation, including Aguirre and Castaneda. They were able to neutralize a faction which had been involved in the April 1944 attempt to overthrow Martínez. This second group was no longer influential by the time that Castañeda took office. A third faction, composed of junior officers, waited in the wings.

Such patterns of cleavage were relatively common in contemporary Latin American military institutions. Factors of training, generation, career orientation, and social class were probably more important contributors to these cleavages than any real or imagined ideological differences that could be derived from readings of the documents put forth by military groups when they assumed power. In El Salvador the cleavages were important, since the armed forces were on the point of embarking on a civil-military experiment in “controlled democracy” and “military reformism” that was to last almost three decades. It must not be forgotten, however, that in their relations with civil society different military factions will overlook their disagreements when the integrity of their institution is threatened. This drive for unity and consensus becomes as important as any specific policy or project that the military in the government may pursue.

The “majors coup” of 14 December 1948 sought to inaugurate a new model in Salvadoran politics. The coup was precipitated by moves by Castañeda Castro that were apparently aimed at extending his mandate to a second term, but it is probable that a new and more institutionalized system of military rule would have come about sooner or later. The political roots of the present crisis in El Salvador may be found in the failure of this experiment and of the deterioration of the form of domination that it entailed. The more profound reasons for the crisis stem from the inability of the new model to solve some basic problems of political organization.

Military Reformism

The experiment inaugurated in 1948 accepted the conventional wisdom that coffee was of predominant importance and that the operation of that sector should be spared any dangerous reforms that might upset the delicate balance of a country with a small territory, a protean economy, and a rapidly growing population. What the military failed to understand was that the operation of the coffee sector was not inextricably bound to the oligarchy in some kind of historical spell that could not be broken.

The country needed structural reform to correct inequities; this was not a matter of ideological preference but a basic question of economic necessity and political viability. For such change a political “opening” was necessary, and this was impossible without the support of the military. Furthermore, despite the unresolved crisis of hegemony, the oligarchy retained enough political influence and economic power to veto any reforms. Any changes had to be produced from the outside by a new coalition. The military could have played a crucial role in this, as it did in other Latin American countries, but it failed to do so.

Instead, during the next three decades in El Salvador, the military controlled but did not dominate the society. It failed to become the hegemonic actor that could replace the oligarchy; it missed a number of opportunities to form a dominant coalition, and it prevented others from doing so. Unable to evolve a lasting social pact that could legitimize its rule, unwilling to turn the control of the government over to civilians, and incapable of articulating a developmental strategy that would modernize the country and erode the socioeconomic foundations of oligarchic power, the military in its political experiment of 1948-72 must be considered a failure. Unable or at least unwilling to make some crucial decisions, it allowed events to take their own course. Moreover, it stood in the way of the emergence and consolidation of participatory institutions that could have rivaled the social influence of the dominant group and introduced a more balanced picture. Although the military lionized some of the more dynamic and progressive forces in El Salvador, it implemented only half-hearted substitute policies, and these seldom got far beyond the blueprint stage.

Essentially, military reformism left Salvadoran society intact. Whatever changes did occur were not planned and were, in most cases, unforeseen. Military government was not oligarchic, but it benefited the oligarchy. Worse still, these governments were all military dictatorships. Republican institutions were never allowed to prosper or even to operate for any length of time. The regime remained authoritarian, torn between the contradictory tendencies of “populism,” “Nasserism,”2 and “reactionary despotism.”3

The Comparison with Mexico

The basic dynamics of this Salvadoran model may be clarified through a contrast with the Mexican model of single-party domination and development through industrialization. This is a frequently made comparison. According to Monteforte Toledo, El Salvador was the only Central American country in which the Mexican formula could have been replicated successfully. Monteforte believed that the following factors made this possible:

1.The matanza of 1932 neutralized the possibility of “revolution from below,” or, more specifically, of a peasant uprising, at least for some time (in Mexico the agraristas were defeated and the peasant faction proved incapable of organizing a government; thus, the chance for a peasant revolt was lost).

2.The military institution emerged as the dominant political actor, filling the power vacuum created by the crisis of oligarchy that began in 1932; this rule was not personal but institutional (in Mexico, the charismatic authority was institutionalized in the office of the presidency itself, and not in its incumbent).

3.The system found equilibrium in a formula of “triple veto,” which defined the power relations between the dominant actors and guaranteed their integrity. The oligarchy retained the veto against developmentalism and against structural changes in agriculture; the industrial bourgeoisie accepted the domination of the army and the oligarchy, but it preserved a veto which excluded the petite bourgeoisie from power and thwarted any attempt to implement a populist formula; and the military monopolized the powers of the government through its control of the presidency and of the political ministries (Interior, Defense, Labor) in order to maintain order and veto any civilian attempt to regain hegemony.

4.The single-term presidency and the renewal of the top governmental positions every five years reduced tensions and allowed different factions to share in the running of the incumbent administration, diminishing instances of violence and conspiracy (removal of top governmental and party elites every six years gives a fluidity to the Mexican system that facilitates the circulation of elites).

5.The middle sectors of the petite bourgeoisie were incorporated into the system through their recruitment into a bloated public bureaucracy.

6.The official party of El Salvador utilized the military command structure as a political machine, particularly during electoral campaigns when local commanders of the national guard acted as agents of the party, mobilizing support, neutralizing opponents, and, when necessary, stuffing ballots or keeping people away from the polls.

7.Urban labor was allowed to organize within certain limits, co-opting the leadership and making it difficult for dissident unions to compete with the tame unions tolerated by the government. The very limited organizational rights of urban workers, primarily industrial workers and commercial employees, were not extended to the peasantry.

8.The peasant sector remained outside the system, since the existing system of coffee exploitation could not be changed. Wages had to remain low, production had to remain labor intensive, and any changes in land tenure patterns had to be made without “serious disruptions,” which would bring about “dire consequences.”4

Even though these elements show a strong resemblance between the system that evolved under the control of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) in Mexico and the Salvadoran system from 1948 to 1972, they mask a number of fundamental differences. An examination of these will help us understand some of the basic flaws and contradictions of the Salvadoran copy.

In Mexico the revolution of 1910 destroyed the liberal oligarchy that grew out of the Reforma and the Porfiriato, laying the foundations for a reformed capitalist state which finally crystallized during the administration of General Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–40). The “active state” that emerged under Cárdenas was based upon a social pact between a new industrial bourgeoisie, government officials, and urban labor, with the exclusion of the military from the dominant party, the compulsory inclusion of the peasantry, and the optional participation of the middle class. The manner in which the Salvadoran state operated and the basic coalition that was accommodated within the official party could not have been more different. Moreover, the Mexican formula altered the nature of the capitalist state that had evolved under the Porfiriato, and it destroyed or neutralized the power of precisely the two actors who not only had managed to survive in El Salvador but, more importantly, had organized a very different party with a very different coalition. These two, the military and the oligarchy, were not interested in promoting a model in which the inclusion of other groups in the official coalition would result in a diminution of their influence.

Party-government relations were also different in El Salvador. The selection of the president was primarily a military and not a party decision. The president ruled as a military man, and not as a civilian or, much less, as a party leader. I say “primarily” and not “exclusively” a military decision because this depended upon the incumbent’s power base, the popularity of his administration, and the oligarchy’s ability to influence the decision. For example, Colonel Oscar Osorio chose his minister of the interior, Lt. Colonel José María Lemus, to succeed him in the presidency for 1956-62. Lemus had not bothered to join the official party until 1955. By contrast, President Molina did not get his first choice to succeed him in 1977. Probably, this was the result of the very bitter confrontation between Molina and the oligarchy over the creation of the Instituto Salvadoreño de Transformación Agraria (ISTA) and Molina’s attempt to introduce some mild reforms into the agrarian sector.5 Thus, Molina’s inability to choose his successor was not the product of an intraparty squabble but was instead a consequence of conflict in the always delicate relation between the oligarchy and the military. Defeated by the oligarchy on a substantive issue, Molina found his ability to sell his candidate to his military peers impaired. In short, the influence of the oligarchy on the selection was indirect, and the president’s inability to choose his successor did not result from a party decision.

At no time were the civilian elites of the party in a position to impose a decision on their military colleagues on the basis of party discipline. The military elites, on the other hand, were more concerned with the integrity of their institution than with the institutionalization of any party. In the process of presidential selection, as well as in decisions on important issues, the military had to reconcile the ambitions and designs of individual officers and officer factions with the need to maintain the principles of hierarchy and discipline and, furthermore, to reconcile these with the exigencies of public policy and the demands of political influentials. Since all of these considerations had priority over party development, it is difficult to see how the normal operation of the Salvadoran model could have contributed to the institutionalization of an official party.

This contrast between Mexico and El Salvador underlines a basic distinction and deeper contradiction which the salvadoreños were not able to solve: in order to build the party the leadership had to become “politicians.” They could do this only at the risk of losing their grip on the armed forces. But the Salvadoran military had a conception of politics which viewed parties, elections, and opposition as a minor annoyance during times of prosperity, and as a threat during times of crisis. According to Juan Felipe Leal, in the Mexican case the differentiation between military elites who became politicians and created the bureaucracies of the government and of the party and those who remained military officers brought about a demilitarization of the party.6 Eventually, civilian supremacy became a fact of political life there. The Salvadoran military was reluctant to abandon the uniform and equally reluctant to accept civilian supremacy.

The other major actor in the Salvadoran coalition, the oligarchy, was able to exercise its influence very effectively through the manipulation of the ideological symbols that it monopolized. Military deference to the laissez-faire liberalism advocated by the oligarchy put all the marbles on the side of the latter. For example, in spite of its relative success in deriving legitimacy from the revolution of 1948, the Salvadoran military could not find a language or set of ideological symbols to challenge those utilized by the oligarchy. Military rhetoric remained a mixture of populism, McCarthyism, and pro-gressivism, which clouded the basic objectives and normative underpinnings of government policy. Declarations of reform were toned down with guarantees of private property; promises of agrarian reform were a double entendre. Since the oligarchy viewed all reforms with suspicion anyway, and since it had sufficient economic muscle and social prestige to command the attention of the media, it was always able to put the military on the defensive.

In Mexico, by contrast, the PRI has the ability to utilize a revolutionary heritage to defend itself and its policy initiatives from conservative attacks. This is not to imply that the Mexican party is truly revolutionary, for anyone familiar with Mexico knows of the ability of the “liberal Machiavellians” of the PRI to clothe everything in lofty rhetoric. However, the Mexican government can justify some of its policies by labeling them revolutionary. In El Salvador this was not possible. The military sought to defend incremental reformism with anti-Communist rhetoric. This only made it and its reformism more vulnerable to attack by the oligarchy, which continued to monopolize the proper vocabulary. Thus military reformism could always be castigated as hasteful, demagogic, and dangerous and injurious, not to the interests of a small and narrow group, but to some basic pillars of Salvadoran society, such as the right of property and the free enterprise system.

The Salvadoran military was also at a serious disadvantage in maintaining the legitimacy of its regime. Its “controlled democracy” remained militaristic, and was resented by civilians. Its rule was tolerated by the oligarchy, but not supported enthusiastically, except when used to curb any stirrings from the lower classes. The military’s inability to transform the state and to produce a new social pact distanced it from other political actors who could have taken the place of the oligarchy in a new coalition. In turn, those actors lacked the ability to match the economic power and political influence of the oligarchy, which they could challenge in only two ways: through a system of genuinely competitive elections or by a new alliance. Neither scheme could succeed without the decided support of the military. A scheme based on competitive elections was out of the question since it would bring to power a coalition unacceptable to the oligarchy and would imply civilian supremacy, which was anathema to the military. A new alliance could have been formed in 1944, 1948, 1960, or, later on, in 1979, but the military lacked the nerve, the desire, and the consensus to do so. This problem remained unsolved in 1980–82.

The military experiment, or the series of military experiments between 1948 and 1972 in El Salvador, failed to resolve the crisis of oligarchy of 1931, which became a crisis of hegemony after the overthrow of Maximiliano Hernández Martínez in 1944. The military failed to supplant the oligarchy as hegemonic actor, it fell considerably short in taking the measures necessary to produce a better balance of political forces, and it stood in the way of others who tried. If, as the Purcells suggest, the Mexican state is characterized by a constant bargaining among elites with different political interests, the Salvadoran state did not provide that option in 1972 and 1979, as we shall see.7

Oligarchic Domination

Before we proceed any further, it may be prudent to clarify what is meant by “oligarchy” in the Salvadoran context. In the language of the classics, oligarchy was simply the selfish rule of a few governing for themselves. In more contemporary terms, the word usually implies a situation in which a relatively small and closed group of economic actors manipulates the market, derives social prominence from that manipulation, and acquires an unchecked amount of political influence as a result. In El Salvador the members of that oligarchy are certainly more numerous than the notorious “fourteen families,” a metaphor that has acquired a reality of its own. Of course this is not an inquiry into the social register but an attempt to determine the composition of that oligarchy, the degree to which it overlapped with the bourgeoisie, and the types of resources which enabled it to continue to play a prominent role in Salvadoran politics and, more specifically, to check the reformism of the military.

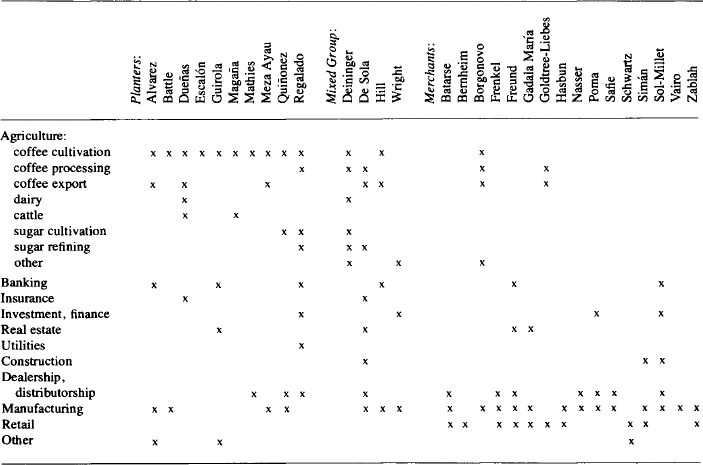

A study by Robert Aubey offers some evidence about the nature of the Salvadoran oligarchy. In his analysis of economic family groupings in El Salvador, which admittedly did not include all the relevant families yet nevertheless produced a representative and valid sample of this social stratum, Aubey detected the existence of three major groups in the oligarchy: planters, merchants, and a “mixed” group of entrepreneurs.8 Rearranged in tabular form, Figure 2-1 presents evidence to show the diversification of this nucleus of the Salvadoran oligarchy.

The Aubey scheme could be expanded as follows: the Dueñas family is also involved in real estate (massively in San Salvador), banking, investment, and manufacturing (the Palomo group is really Dueñas); the Alvarez family (oldest branch) is also involved in cattle and the dairy industry; the Escalón family also deals in real estate; the Meza Ayau and Quiñónez families also have ties to banking (through intermediary junior partners) and real estate. These modifications were suggested by someone who is a well-qualified observer, but since it is difficult to determine how much change has taken place in the overall configuration of relations between the top entrepreneurial groups, these changes have not been included in the Aubey scheme.9 But even considering these new data, the fact that some of the information is incomplete, and the relative obsolescence of the study, his survey remains fairly accurate.

Using Aubey’s data, we can make the following conclusions. First, “diversification” in El Salvador did not increase the social heterogeneity of the dominant group. The older families, represented in the first group (planters), simply moved outside the coffee sector into other areas of the agricultural sector and into other areas of production. It is difficult to assert their dominance over these other areas, but given the concentration of ownership and the small number of large enterprises, it is probable that their presence in those other sectors was, to say the least, influential. Eduardo Colindres suggests that this presence was indeed very strong.10

Second, the economic diversification of the planter group did not extend into retail trade, which remained very much under the control of the merchant group. The families in this group are of more recent vintage in Salvadoran society and of varying national background—notice the probable differences in ethnic origin among the surnames of this group. Conversely, very few merchant families seem to have gone into agriculture. This could suggest, on the one hand, that the classic cleavage between planters and comerciantes, so characteristic of the nineteenth century in some of the countries of the Isthmus, was still present in El Salvador scarcely a decade ago. On the other hand, Aubey’s awareness of such a notorious division may have influenced his perception of the contemporary configuration. In either case there is little doubt that the data presented in Figure 2-1 show one group of families with a relatively tight control over coffee and some spillover into the service sector, and a different group of families concentrating its activities in commerce and manufacturing.

These tentative inferences lead to two questions: first, which of these was really dominant and, second, what was the difference between the oligarchy and the bourgeoisie?

Lacking interview data on the normative perspectives of members of these groups, it is impossible to state definitively who was really who. According to the results of important research, moreover, social background is a poor predictor of elite attitudes, which, in turn, are poor predictors of elite behavior. In short, membership in one economic group is a relatively unreliable indicator of oligarchy status unless this is validated by members of the group in question. In this case, at least a partial validation of the composition of the core element of the oligarchy is at hand.

FIGURE 2-1

Patterns of Ownership and Sectoral Specialization of Some Salvadoran Families

Source: Adapted from Robert T. Aubey “Enterpreneurial Formation,” pp. 272–76.

It is a bit harder to determine who was really dominant, for some of the relevant data are difficult to get or even unobtainable: for example, data on rates of profit by sector for the Salvadoran economy or the balance sheets of individual enterprises.11 Colindres’s “La Tenencia de la Tierra,” a condensed version of his Fundamentos Económicos de la Burguesía Salvardoreña, however, as well as a series of articles and sources, shed some light on this question and allow additional inferences on how much control existed in the agricultural sector, who benefited from it, and what the consequences of this concentration were.12

Using the Third Agricultural Census as a point of departure, Colindres estimated that in 1970–71 approximately 250,539 explotaciones (farms), or 92.5 percent of all the farms, accounted for only 27.1 percent of the land under cultivation.13 By contrast, the 1,941 farms larger than 100 hectares,14 representing 0.7 percent of all farms, accounted for 38.7 percent of the land under cultivation at that time.15 This situation had not changed in 1978-79, since only 4 percent of the estimated 40,800 growers controlled 67 percent of all the coffee produced in that harvest year.16

A lopsided distribution of agricultural property, however, is only one aspect of the economic domination by the oligarchy in El Salvador. According to Luis de Sebastián, as one moves from tenure to cultivation to processing and to export, the number of enterprises declines—as one may expect—and therefore, the chances for excessive concentration increase. In Sebastián’s view, El Salvador witnessed even more concentration, as most of the processors were also exporters.17

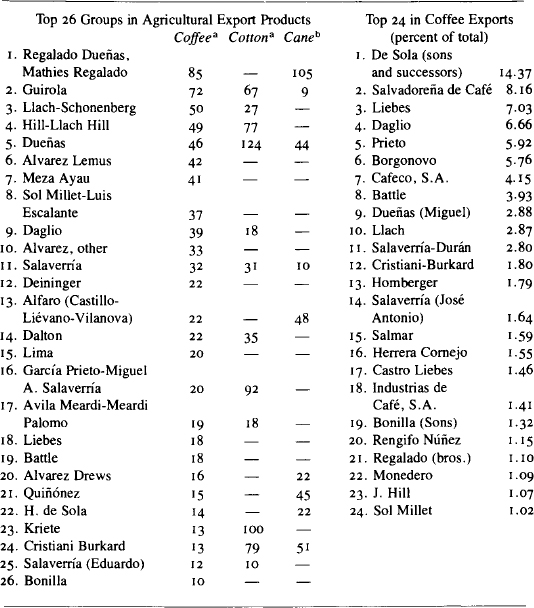

Data compiled by the Seminario Permanente de Investigación of the Universidad Centroamericana Simeón Cañas (UCA) show that twenty-three of the twenty-six family groups producing ten thousand quintals or more were also beneficiadores, that is, engaged in processing.18 In addition, these twenty-six included twelve of the fourteen largest producers of cotton and nine of the top ten sugar growers—although the tenth happened to be the largest sugar grower.19 If these twenty-six family groups are compared to the top twenty-four identified through the standard used by Colindres—exporting at least 1 percent of the total export of Salvadoran coffee—one gets a fairly precise idea not only of the extent of the concentration but also of the overlap in ownership in different aspects of the exploitation of coffee and of the main agricultural exports (see Figure 2-2).

The determination of who were the core families of the oligarchy will be left to others, since this is not, after all, the main purpose here. What the evidence presented thus far suggests is that Sebastián did not exaggerate. To put it in his own words: “In summary, the power pyramid of agricultural exports rests on the large landed estate and it culminates in the [control] of exports. . . . In the Salvadoran economy oligarchic power does not consist of concentration but omnipresence, that is, that this [concentration] extends to all the key productive sectors.”20 The names of the groups and individuals included in Figures 2-1 and 2-2 belie the conclusion that there was a perfectly identifiable set of fourteen key families who dominated the Salvadoran economy. But the data here presented should at least establish a plausible and valid case for the argument that too many crucial aspects of the economy were in the same hands.

A number of Salvadoran social scientists have offered more precise descriptions of the makeup and internal dynamics of the oligarchy power block. Rafael Guidos Véjar talks about two main factions:

A frente agrario [an agrarian front] and grupos industrializantes [industrializing groups]—[the former are] political forces who . . . identify with the interests of agrarian capital [while the latter are] those political forces who, although they share in and reenforce the interests of agrarian capital, strive to make their own industrial capital faction dominant economically and hegemonic politically. [The relationship between the two factions resembles a] permanent process of integration and disintegration of these frentes and grupos [in which] their internal dynamics, the circumstances in which they redefine themselves vis-à-vis the popular groups . . . produce “equilibrating compromises.”21

Italo López Vallecillos perceives a similar configuration consisting of

a faction denominated agrario-financiera [agro-financial] opposed to any attempts to transform the rigid framework of land concentration [and] low salaries, [cornerstones of] a plantation economy that serves as the basis of its profits . . . and the agrario-industrial-financiera [agro-industro-financial] faction which seeks to impose new patterns of agricultural diversification. [During crises] both factions are forced to joust with respect to the type of domination that ought to prevail in the country. This hegemonic dispute . . . allows that other class factions mobilize themselves . . . seeking to increase their own influence. . . . For example, whenever the price of export products is relatively stable, the agro-industro-financial faction seeks to introduce changes in the economic system, redistributing more social benefits to labor and favoring less authoritarian political structures.22

FIGURE 2-2

Top Economic Actors in Agricultural Exports and Coffee Exports

Source: Colindres, “La Tenencia de la Tierra,” p. 471.

a. Thousands of quintales

b. Thousands of metric tons

The duocentric models of the Salvadoran power block presented by Guidos Véjar and López Vallecillos are naturally not without fault, but they do have much empirical validity and conceptual sophistication. In addition, these models parallel others that may be found in the Salvadoran literature on this question, suggesting a consensus of scholarly opinion. They depict a scheme of “shared economic power,” in which the more traditional (agro-financial) faction adjusted to the limited industrialization afforded under the model of export agriculture without having to accept the social and political consequences of that transformation. Under the existing circumstances it was unlikely that industrialization would be the key to a new system of political domination in El Salvador.23

The continued dominance of the traditional faction was inextricably bound to a process of concentration described as a “magic square” of oligarchic domination, which included control of production, export, finance, and land tenure.24 The description of how this concentration came about deserves a major historical essay, a task undertaken in part by David Browning and by Knut Walter.25 For our purposes here it is more important to understand how this mechanism has operated in contemporary times, reproducing and reinforcing itself.

The profits realized by the major planters were exceedingly high through most of the period from 1948 to 1979. In the late 1940s El Salvador was, in the opinion of an expert source, the most efficient producer of “mild arabica” coffee in the world. Production costs were estimated by the Compañía Salvadoreña de Café at 12 cents per pound for 1948, and in the 18 to 20 cents per pound range for 1949. A different computation by a more impartial source, however, suggested that the real costs may have been closer to 7.3 cents per pound during those years.26 In addition, a careful study by Daniel and Ester Slutzky calculated the profits of the large planters at 30 percent during the late forties, 45 percent in 1950-57, and 34 percent in 1962-64.27

All of these estimates are subject to criticism and revision. Yet there is little question that the Salvadoran economy produced the levels of investment needed to keep export agriculture going, as well as a surplus to apply to other sectors.28 According to careful calculations by Joseph Mooney, gross fixed domestic investment jumped from 4.5 to 14.6 percent of GDP between 1945 and 1965—in real terms, fixed at 1962 prices.29 In his conclusions, Mooney stated that investment had not only strengthened but acquired a cyclical insensitivity. In other words, investment capital was available regardless of the level of export prices. Mooney seemed correct in saying that manufacturing and commerce had become important sources of growth at the time; however, his appraisal that this picture signified a “break from the pattern of development which prevailed in the past” seems to have been optimistic and premature.30

One reason why a new pattern of development failed to take root was precisely because the control of the profits and the surplus remained in few hands. According to Luis de Sebastián, Salvadoran finance had originated in the circulation of the surplus generated by agricultural exports. In recent times, the link between agriculture and finance has remained strong. For example, the ownership “of the four oldest banks—Salvadoreño, Comercio, Agrícola Comercial, and Capitalizador—is linked to [that sector, while] the nexus between the four other largest banks—Crédito Popular, Cuscatlán, Financiero, and Internacional—and the agro-exporting sector is not so notorious. . . . [Finally] the Banco Hipotecario is linked to official interests in that sector through the Compañía Salvadoreña de Café.”31 Small wonder that between 1961 and 1975 the share of agriculture in commercial credit increased in relation to the total amount of credit available in those years. A study by Melvin Burke uncovered evidence that during those years the coffee sector received an average of 50 percent of all agricultural credit and 15.2 of all commercial loans, as suggested by the data presented in Table 2-1.

There was nothing inherently conspiratorial about this. The pattern of credit extended for commercial operations was simply the product of concentrated and overlapping ownership and the network of relations resulting from it. Naturally this most benefited the largest planters, who could supply collateral and assure repayment. Burke suggests that, in general, Salvadoran finance followed an iron law of sorts of “lending to those who own something.”32

Burkes’s figures, on the other hand, do not show that the other sectors were starved for credit but merely that agriculture took more than its due share, especially if one considers that the percentage of GDP contributed by agriculture began to decline in this period of time. There was credit to finance other activities, but this was tied to the network of interests described by the evidence presented in Figures 2-1 and 2-2.

In the late sixties, at the time when Aubey collected his data, the industrial sector of the Salvadoran economy employed 64,722 workers in 4,220 enterprises owned by 3,389 proprietors.33 These figures would work out to about 15 workers per firm, hardly the type of establishment characteristic of a robust industrial sector. On the other hand, David Raynolds may have been correct in arguing that the number of “decisive” economic actors increased from 4,000 in the thirties to 24,000 in the early sixties, but it is hard to see how he could conclude that the system was not closed to new entrants and that even better opportunities would open up to those not yet participating in economic decisions.34

The late sixties marked the time when the bourgeoisie, dominated by the industrialists, established an important foothold in the commerce of the Isthmus with an aggressive export policy. This new avenue was beginning to make them somewhat stronger and more independent of the traditional oligarchy, since it provided them with profits that were not so enmeshed in the complex network of domestic economic relationships described above. But the 1969 “soccer war” with Honduras effectively closed that avenue.35 There remained the possibility of association with transnational capital interested in diversification. But the country did not provide a very large market, and foreign capitalists did not need Salvadoran associates to invest elsewhere in the Isthmus. At any rate, neither of these would have made Salvadoran industrialists more independent, and the bulk of transnational capital went to Guatemala anyway. Therefore, the balance of economic power “shared” by the traditional agro-financial oligarchy—or “agrarian front”—and the agro-industro-financial bourgeoisie remained in favor of the former. (To simplify matters I will use the term oligarchy to refer to the faction that dominated finance and export agriculture, reserving the term bourgeoisie for those upper-class elements whose presence was stronger in commerce and industry.)

A bourgeoisie did indeed emerge in El Salvador, but it remained bound to the traditional groups or at least dependent on them for the finance of major projects. The bourgeoisie remained unable to secure the resources necessary to embark on the type of economic projects that would have made it socially and politically hegemonic. A democratic regime would not have been the inevitable result of bourgeois dominance, but without that dominance a new coalition could not be formed to challenge the traditional oligarchy from a solid economic footing. In short, a new alliance and a new social pact were not forthcoming, and lacking that firm economic base, the more progressive element of the Salvadoran upper classes remained unwilling to attempt more drastic options, such as a populist alliance with the lower class, much less a reformist government based on civilian supremacy.

The deterioration of the material conditions of life of most families in the Salvadoran countryside was a direct result of the oligarchy’s magic square of economic domination. Despite a nominal tenfold increase between 1952 and 1979, the salaries of agricultural workers remained at or below subsistence (see Table 2-2). In 1975 the level of subsistence for an average family of six was estimated to require an income of 1,760 colones per year, with 1,332 colones just to cover nutritional requirements. During the 1970s, a majority of the rural families saw their situations grow progressively worse, following the massive return migration produced by the war with Honduras. Between 1971 and 1975 the proportion of agricultural families without land increased from 29 to 41 percent of the total, compared to 12 percent in 1961.36 This is reflected in the figures presented in Table 2-3.

Of course barter and other ingenious schemes in the informal economy of the poor can provide some relief in situations like this. The well-documented symbiotic relationship in which minifundio, provide subsistence—and some basic staples for the domestic market—for poor agriculturists employed seasonally in the latifundia can also serve to ensure the loyalty of the peasants to a dominant group. Thus, those most directly affected by the domination of the magic square, the massive number of unemployed and underemployed Salvadoran peasants providing the “redundant labor” indispensable to Salvadoran export agriculture, may not have been ready to revolt against their exploiters.

Meanwhile, the proprietors of the farms engaged in the production of export crops got a very nice bargain. El Salvador was a predominantly rural country with a very high rate of population growth and a slowly expanding industrial sector incapable of absorbing increasingly larger proportions of the work force. There was a fixed, guaranteed demand for employment that kept labor costs very low, and planters had to worry about salaries during only three or four months.

Inevitably, a demand for the redress of this historical grievance became a permanent feature of the political process, made more urgent by deteriorating conditions in the countryside. The corollary is that, if forced by the government, the planters had a sufficient cushion to assimilate reform. Given the buffer that their surplus and their profits provided, one could imagine that the traditional oligarchy would eventually reconsider and yield somewhat. But this was not to be.

Following the matanza of 1932, political conditions in the Salvadoran countryside were tightly controlled through a combination of paternalism, unfulfilled promises, and repression. The particular blend at any one time depended on the ups and downs of the export market, the orientation of the incumbent government, and the degree of agitation about reform. The peasantry remained outside the political process, unable to evolve autonomous organizations that would give it an independent voice. Instead, independent organizational attempts were resisted ferociously, and the government tried to bring the peasantry into its Salvadoran Communal Union (UCS).

When conditions deteriorated so far that even the government decided that some action was necessary, the oligarchy resisted and thwarted the initiatives; this happened in both 1973 and 1976. Government arguments that “reform now was a life insurance for the future” failed to convince the traditional oligarchy. To them, reform was “appeasement”; their own assumption seemed to be that, if necessary, they could repeat the “lesson” of 1932.

Like the bourgeoisie, the peasantry and the Salvadoran working class needed an ally, some group which could join forces with them and dislodge the monolith represented by the magic square. It can be argued that the post-1972 developments in Salvadoran politics have been either a series of failed and short-lived initiatives to build new alliances or contrived and short-sighted attempts to provide temporary respite from cyclical crises. The oligarchy has weakened somewhat, but it remains capable of taking bold initiatives to save itself.

Oligarchic domination in contemporary Salvadoran society rested on a scheme of “shared economic power” in which the more traditional (oligarchy) faction continued to dominate a weaker modernizing faction (bourgeoisie). The concentration of land, production, exports, and finance benefited the two, but preserved the power of the oligarchy over the bourgeoisie with this magic square of domination as the centerpiece. The armed forces, who had assumed control of the government, refrained from too much tampering, so that the private sector, led by the oligarchy, could continue to provide foreign exchange, revenue, and prosperity for some, although probably not too many.

The point is frequently made that the fatal flaw of socialism is that it concentrates too much power in the state, creating an economic monolith that suffocates freedom. In El Salvador, the agents of concentrated economic power, who managed to stifle political freedom and thus prevent the breaking down of their monolith, masqueraded as defenders of “free enterprise.” From the standpoint of the established order, which offered no genuine avenues of redress, any effective solution had to be “subversive,” since it had to come from a new set of actors. To understand this is to understand what is in crisis in El Salvador, and to identify solutions to this crisis is to identify what deserves to be saved, the pretense of free enterprise or the real thing.