Chapter 3

Parties and Politics in El Salvador, 1948–1977

The Cycle of Salvadoran Politics

According to Italo López Vallecillos, contemporary Salvadoran politics has followed a cyclical pattern that is related very closely to the cycle of export commodities. López Vallecillos sees the period between 1948 and 1977 as divided into two stages of roughly twelve years each: one from 1948 to 1960, and the other from 1962 to 1975.1 Neither dogmatic nor deterministic, this perspective is simply a recognition of a basic feature of Salvadoran political economy, and is probably shared by Salvadorans of very diverse ideological stripes. The nexus between economic crisis and political conflict is relatively straightforward.

Economic crises trigger events with political and military significance in which middle sectors and factions of the dominant classes intervene, [seeking to introduce] new modalities of expression into the system. [However] not always are economic crises a decisive factor of change or readjustment, although . . . mass movements are pressure elements [comparable to economic crises] especially when articulated with classes gaining ascendance; . . . The cyclical nature of our economy . . . reinforces the power of the agro-financial faction [of the oligarchy] which is the only one that, during economic crises, can wield foreign exchange to show the need to maintain [a] capitalist model based on agriculture.2

These considerations are very pertinent and worthwhile as a preface to any discussion of contemporary partisan politics in El Salvador, for given the characteristics of the military model and the outcomes that such a model could allow, it may seem somewhat esoteric to speak of party politics in that country. Moreover, the majority of the parties to be identified in this chapter were not really political parties. Finally, and most important, the fatal flaw of the Salvadoran system inaugurated in 1948 is that in trying to prevent partisan and electoral politics from disrupting the established order, the military precipitated a more direct confrontation between Salvadoran classes.

Yet the stubbornness with which the oligarchy resisted the institutionalization of a party system and competitive elections in El Salvador suggests that it clearly understood the socioeconomic implications of such a development. Since the system of political domination that prevailed in El Salvador between 1948 and 1972 was based on an exclusionist and unstable alliance between the military and oligarchy, since the regime enjoyed relatively low legitimacy, and since it was managed by an actor which had control but not hegemony, it was a foregone conclusion that elements left out of the official coalition would eventually mature and evolve their own avenues of political participation. It was also inevitable that those elements would challenge the system, taking advantage of cyclical crises to force the government to respond or repress the challenge.

The institutionalization of a party system would have reduced tensions and introduced the types of incrementalist strategies that aie characteristic of a political process that includes regularly scheduled and truly competitive elections. Class interests would have become intertwined with electoral alliances, and the oligarchy could have spread the inevitable reductions in its position over a relatively long period of time. To be sure, there is no guarantee that this would have been the case, but the oligarchy and the military refused to enter into a game that entailed any degree of uncertainty and set out to pursue a partnership in which the latter would “maintain order” while the former managed the resources that sustained that order. Apparently, the military believed that it would be able to follow the Mexican model and consolidate a system of one-party domination. The oligarchy, for its part, seemed resigned to leaving the governing to the military, provided it did not embark on dangerous experiments. Both seemed to understand the functional requirements of their alliance, including the measures necessary to keep it afloat during times of crisis, although it is hard to imagine that they believed in their unyielding ability to prevent change.

The Party System of El Salvador

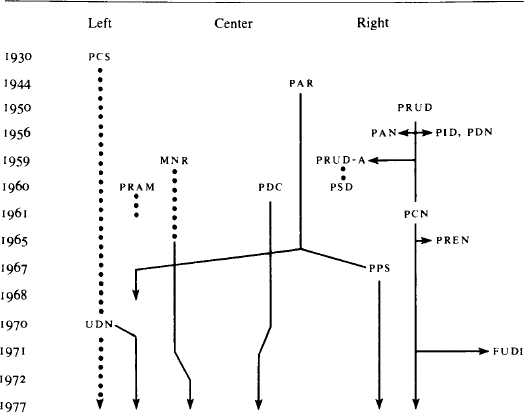

As a point of reference for the discussion to follow, Figure 3-1 traces the trajectories of the more relevant parties in the Salvadoran system. These include the two official parties, the Partido Revolucionario de Unificación Democrática (PRUD), which lasted from 1950 to 1960, and its successor, the Partido de Conciliación Nacional (PCN), which was unveiled in September 1961 and, although apparently moribund, is still active two decades later. The splinters of the PRUD-PCN are also included in the figure.

Some of the longer lasting and more representative parties of the opposition include—in chronological order of their founding—the Partido Communista Salvadoreño (PCS), the oldest party in the country; the Partido Acción Renovadora (PAR), which underwent a very curious metamorphosis which led to a split and its eventual disintegration in the mid 1960s; the Partido Demócrata Cristiano (PDC); and the Movimiento Nacional Revolucionario (MNR). This list would have to include the Partido Popular Salvadoreño (PPS), formed by the more conservative members of the PAR, which sought to articulate a different type of opposition from that represented by the first four.

The emergence and evolution of these parties were tied to the cycle of Salvadoran politics described by López Vallecillos, and while it is difficult to identify the constituencies that they represented with absolute accuracy, their fortunes tell us a lot about the major events of contemporary Salvadoran politics. In addition, their trajectories also reflect the limited success enjoyed by the official party and the degree to which political actors excluded from the official coalition were able to challenge its real or presumed dominance.

The track of the official party can be divided into two periods: one from 1950 to 1960, and the other from 1961 through 1977. The mini-revolution of 1960 was a watershed. It brought about a fundamental change in the context in which the party operated and limited its ability to serve as intermediary and arbiter, functions which a dominant party is supposed to fulfill. In both 1950 and 1961 the party was organized to serve as a political vehicle of the civil-military coalition, and not as an instrument of the ambitions of a personalist military leader.

The PRUD-PCN was not a mass party. It did not thrive on mobilizing the population, except to express support for government policies. The party did not have a permanent organizational structure; nor did it have much to do between elections. None of its deputies in the unicameral legislature or its municipal officials “elected” under the banner of the official party turned to it for guidance during his term of office. In reality, there was nothing to turn to: no party program or platform, no sectoral leadership to consult. While the official Salvadoran party incorporated public employees, retired military, and agricultural workers into its ranks, its de facto leadership came from the High Command of the armed forces and high government officials.

Compared to the minuscule bands that tried to present themselves as parties in order to serve as conduits of the electoral ambitions of a maverick officer or two, the official party was an impressive machine of patronage and electoral mobilization. Created to serve the ends of official policy, the party reflected the inclinations of the government in power, and this tended to create splinter groups, as represented in Figure 3-1. By contrast, the ephemeral and ad hoc groups, such as the Partido Auténtico Nacional (1956), the Partido Institucional Democrático (1956), the Partido Demócrata Nacionalista (1956), the Partido Republicano de Evolución Nacional (1965), and the Frente Unido Democrático Independiente (1971), were organized to promote the candidacies of Colonel Luis R. Flores, Colonel Rafael Carranza Anaya, Major José Alvaro Díaz, Colonel José Alberto Funes, and General José Alberto “Chele” Medrano, respectively.

FIGURE 3-1

Evolution of the Salvadoran Party Spectrum, 1930–1977

Note: Parties are arranged on a Left-Right continuum according to their position on the issues of civilian supremacy and reform of the existing socioeconomic structure. Solid lines represent periods during which the parties enjoyed legal recognition and were able to participate in elections. Broken lines represent periods during which the parties were being organized or when they did not meet one or both of the aforementioned conditions.

The fact that these mini-parties were organized reflects the diversity of opinions within the military institution, as well as the fact that there was always a generous supply of, for the most part, extreme conservatives outside the official party smarting at the “sell-out” by government reformism. A good example of both is the case of Chele Medrano, who, in spite of the support of the S ala venía family and the votes of the members of ORDEN, did not make much headway in the bitter election of 1972. Medrano’s failure, which included arrest for conspiring against the government, suggests that the dominant party provided the military with a mechanism that preempted the actions of mavericks like Medrano.

The official party, the PRUD, was the creation of Colonel Oscar Osorio, who had lived in Mexico and had the opportunity to observe the operation of the Mexican system. Osorio had led the “majors’ revolt” that deposed General Salvador Castañeda Castro on 14 December 1948. But the dominant Salvadoran party could no more be “revolutionary of democratic unification” than Mexico’s PRI could become “institutional revolutionary.” At bottom, neither really wanted to emphasize “revolutionary.” Thus the Salvadoran emphasis on unification and the Mexican emphasis on institutions.

During his term (1950–56), Osorio adopted the reformist rhetoric of the Revolutionary Council of 1948 and pursued some of its policies as well. This emphasis may have been genuine, but Monteforte Toledo probably went too far when he included the PRUD-PCN among the social democratic parties of the time in Central America.3 To be sure, Osorio’s fallout with Lemus resulted in the formation by the former of the PRUD-A (auténtico), which later became the Partido Social Demócrata. But names alone will not do. Neither will the fact that although he may have harbored social democratic ideas, Osorio failed to champion the cause of one of the most important contributions of social democracy to Latin American politics, namely, civilian supremacy.

Osorio’s reforms concerned some aspects of the social situation, primarily the problem of agricultural labor and the creation of the Social Security Institute (ISSS), the Urban Housing Institute (IVU), and the Rural Settlement Institute(ICR). But Osorio’s reformism was epitomized by a series of infrastructural works—continued by his successor—which reflected the developmental approach of his government. Most notable among these were the works coordinated by the Acajutla Port Authority (CEPA) and the Río Lempa Hydroelectric Authority (CEL). Apparently, this kind of project, as well as the economic policies of his government, strengthened the interests of the oligarchy.4 This emphasis on the development of infrastructure made the PRUD attractive to some of the more dynamic elements in the society, and it was able to depend on the elite sectors for its leadership and to attract the support of middle-class elements recruited into the expanding government bureaucracy.

In spite of his reformism, Osorio reached an accommodation with the oligarchy. The economy was prosperous, and part of his scheme was to create incentives for investment and diversification. The course of the Guatemalan Revolution made him especially vulnerable to accusations of softness toward leftism, and he left the peasant sector alone. The inclusion of industrialists in his coalition, as well as some middle- and working-class elements, could imply the kind of populist coalition typical of the contemporary Latin American systems, but the presence of the oligarchy in the coalition helped to keep Osorio’s populist tendencies in check.

In the elections of 1950 and 1956 the PRUD had to contend with the opposition of a party that initially appeared to be the electoral vehicle of a figure representing the more progressive faction of the military, Colonel José Asencio Menéndez. Originating in the huelga de brazos caídos (slowdown strike) that contributed to the creation of the appropriate climate for the overthrow of Martínez in 1944, the Partido Acción Renovadora (PAR) is one of the more interesting of the time. This party supported a return to civilian rule, although it endorsed the laissez-faire approach to economics favored by the oligarchy. The PAR could have been a viable alternative in 1944 had the junta headed by General Andrés Ignacio Menéndez not been overthrown by the coup of Colonel Osmín Aguirre, which was instigated by the more reactionary elements of the oligarchy. General Menéndez wanted a free and open election, an election that could have been won by physician Arturo Romero.

All this is pure speculation, but it does give an indication of the kinds of individuals that banded around the PAR at the time. In 1950 the party obtained a respectable 43 percent of the presidential vote, while government manipulation of the 1956 presidential race assigned to the PAR candidate, Enrique Magaña Menéndez, a mere 3 percent. Magaña and the successful PAR candidate to the mayoralty of San Salvador, economist and bank president Gabriel Pilona Araujo, were part of the bourgeoisie. Therefore, it seems possible to conclude that the PAR played the role of opposition in these elections, serving as a vehicle for and an alternative supported by the more progressive elements of the oligarchy and the bourgeoisie.

The PAR was joined in the election of 1956 by another party, the Partido Acción Nacional (PAN), organized around a civilian figure, Roberto Edmundo Canessa, a wealthy planter who financed his own campaign and who had served as minister of justice and of foreign relations under Osorio. Canessa’s candidacy was disqualified on “technical grounds,” and he was one of the noisiest protesters of the electoral fraud perpetrated by the PRUD in that year.

If Osorio turned to repression at the end of his term to counteract the spillover of the Guatemalan process in El Salvador, his successor, President José Maria Lemus (1956–60), turned to repression to quell the unrest that accompanied the deterioration of the economy beginning with a drop in coffee prices in 1958 and the increasing agitation produced by the example of the Cuban Revolution. Enthusiasm for the Cuban model of 1959–60 crystallized in the formation of the Partido Revolucionario Abril y Mayo (PRAM), which drew its leadership from the university community. The PRAM was denied legal status in July 1960.

The disruption and unrest in 1960 indicated that the PRUD had failed to form a broad coalition and that the existing party system did not provide outlets for all the relevant and viable political options. In an effort to reequilibrate his government, neutralize student and labor agitation, and reorganize the governing coalition, Lemus announced a program of reforms in late July. He organized a demonstration in August, attended primarily by campesinos trucked into San Salvador. The church hierarchy lent support to his initiative, but both the church and the government were caught in a bind, preaching reform and denouncing Communism at the same time.

The problems that Lemus encountered near the end of his term and his reactions to them are not unlike the situations that other military rulers faced in their terms as they tried to settle problems of succession. Typically, these problems were influenced by or were a part of other factors, including attempts by the oligarchy and the bourgeoisie to influence the selection of the new president or to float their own candidates if dissatisfied with the official choice and opposition calls for a free and fair election, which, in some cases, would have been lost by the official party.

Thus, Salvadoran military presidents approaching the end of their terms often increased the populist content of official rhetoric, launched a “new” program of reforms, cracked down on the liberal opposition and staged an outright electoral fraud, or provoked a confrontation with the traditional oligarchy and the conservative elements of the bourgeoisie. These are typical of most of the crises of succession from 1948 to 1977, aggravated, in some cases, by the commodity cycle, as López Vallecillos has pointed out.

The Mexican system has also confronted crises similar to the one that confronted the Lemus government in 1960, but when attacked by conservatives, threatened by former presidents and their cliques, and beset by economic difficulties, a Mexican president can normally count on the support of political actors who may not love the government and its party but who, like him, share the center of the Mexican political spectrum. A president who represents that center position has the support of a party organized as a broad coalition of middle- and working-class elements, as well as of progressive elements of the industrial bourgeoisie, and can count on the legitimacy of the Revolution. In the Salvadoran scheme, however, the Right was the center of the political spectrum, there was no permanent coalition and no party to fall back upon—nor could these be organized overnight—and there were no historical loyalties to bind substantial sectors of the public to the dominant party. There was just an electoral machine that operated intermittently and a patronage network which fed on itself.

Part of Lemus’s problem may have been that, according to some accounts, he had begun to contemplate the prospect of staying in office for another term. This was not allowed for in the system that Osorio had crafted so carefully, and the latter organized an “authentic” PRUD to emphasize that fact. Lemus’s predicament then became desperate. He was threatened by Osorio, had lost the confidence of the oligarchy, was detested by the Left, and was unable to woo the middle class. He lashed out at some of the traditional adversaries of the military, including the General Association of Salvadoran University Students (AGEUS), the newly emerging General Confederation of Salvadoran Workers (CGTS), the PRAM, and opposition figures like Canessa, who died as a consequence of a severe beating, but he was nevertheless overthrown on 26 October 1960. His departure marked a new opportunity to bring about a process of peaceful transition to democracy—and the repetition of a familiar pattern in which such a process was derailed by obstructionists.

The Junta of 1960

In contemporary Salvadoran politics, the formation of a junta is the somewhat inevitable sequel to the overthrow of a military executive. The junta that came to power to replace Lemus was the third provisional executive of this century in El Salvador, and one of the more diffuse and contradictory, combining relatively junior officers and professionals with university affiliations. The junta’s intentions and possibilities were unclear as it took power, which may have prompted the United States to withhold recognition until December. To assuage the Left and the moderates the junta assured them of its intention to conduct a free and open election soon. It also moved to try to gain the support and confidence of the military, but on 25 January 1961 the junta was replaced by a directorio cívico-militar (civil-military directorate), which justified its coup as a “necessary reaction to the dangerous political tensions that had built up as a consequence of the [previous] Junta having allowed extremist forces to run around wild in the country.”5 Thus, a group of genuine aperturistas working toward a transition were replaced by obstructionists who favored a controlled blueprint and a return to business as usual.

The coup probably served two objectives. The first was to assure that none of the “radical” actors who had coalesced around the junta had even the remotest chance of victory through elections. The coup came two days after a congress in which nine parties—including the PRAM, the recently formed (December 1960) Partido Social Demócrata (PSD), which Oscar Osorio had helped organize, the PAR, the Partido Acción Nacional (PAN), founded by the late Canessa, the Partido Auténtico Constitucional (PAC) and the Partido Institucional Democrático (PID), which had supported military candidates in the presidential race of 1956, the Partido Unionista Centroamericano (PUCA), which had existed for some time but had never presented its own candidates, and the recently formed Partido Acción Democrática (PAD) and Partido Demócrata Cristiano (PDC)—and six professional organizations met to draft a new electoral statute.6

A second and more important objective was simply to prevent the consolidation of an alternative coalition that, in or out of power, could begin to attract military support and thereby divide the institution. Some of the members of the prospective coalition came from the oligarchy, but they were primarily individuals who could put together a populist coalition and try to bring about a program of reforms outside the blueprint for control envisaged under the 1948 model. Basically, the motivation of the military was to retain control of the government, since, from its point of view, only the armed forces could guarantee the integrity and continuity of the “republic.” Attempts to institute a process of transition through elections went against this blueprint and, therefore, had to be neutralized.

The PRAM was persecuted, and Osorio, a potentially disruptive influence but certainly not a radical, was exiled. The remaining parties were invited to form a council to draft the new electoral statute. But, for the most part, the actions of the parties gave the military no reason for alarm. The PID and the PAD were simply ignored. The PAC and the PAN were really vehicles for the personalistic ambitions of certain military officers, and the PUCA was insignificant. Only the PAR and the PDC had the possibility of making some inroads in the legislature.7

Apparently, the military had something in mind in addition to electoral reform. According to PDC leader José Napoleón Duarte, colonels Julio Adalberto Rivera and Aníbal Portillo, both members of the directorio, sought the support of his party in exchange for all seats in the one-house legislature. This overture might have been an attempt on the part of the military to co-opt some of the doctores and middle-class professionals that Colonel Rivera wanted to enlist in the official party. Since there was an agreement between the eight principal leaders of the PDC not to collaborate with governments that came to power illegally, however, Duarte rejected these entreaties.8 Rivera made similar moves toward the PAR, hoping perhaps to capture the support of dissident bourgeois elements that had gravitated in that direction, but he was equally unsuccessful. He coupled these private overtures with vague public warnings about dangers from the Left and the Right. Dr. Feliciano Avelar, another member of the directorio, spoke of the need to set up a dictatorship if a civil-military alliance was not forthcoming. This may have been an indication that the military was under pressure quickly to define the nature of the new regime, or it could have been the military’s way of bringing the oligarchy back to the fold by threatening that its place could be taken by others.

Colonel Rivera became the leader of the directorio. Token civilian participation was discontinued when most civilian members resigned in April. His provisional government enlarged the scope of state regulation of the economy with the nationalization of the Banco Central de Reserva and of the Banco Hipotecario de El Salvador and some legislation concerning rural labor; short-term measures adopted included restrictions on the export of capital and reduced rents.9 To justify and legitimize these measures the directorio identified them with the objectives of the Alliance for Progress. This tactic may have been designed to give the government some respite from ideological blackmail by the oligarchy, but the oligarchy criticized it anyway, since it did not care much for the Alliance for Progress in the first place.

The year 1960 marked another opportunity for a genuine process of democratic transition in El Salvador. If it had succeeded, the system probably would have stabilized at the center-right, not the right, lower- and middle-class loyalties could have been engaged with the prospect of a possible electoral victory at some future date, and the moderate Left could have been incorporated. Instead, deciding to give their model one more chance, the military conspirators of 1960 made Rivera the new military president, and this time they tried to consolidate their one-party domination with a fairly broad and representative coalition. The populist option had been liquidated with the junta, however, and since the search for new partners was confined to what they perceived as centrist alternatives, the effort was largely futile. Neither the PAR nor the PDC was interested, and even these parties were a far cry from the mass-based multiclass party that the military needed to effect a genuine copy of the Mexican model.

Moreover, any gains in widening the base of support could have come only at the cost of more strained relations with the oligarchy. The military’s, or at least Rivera’s, attempt to consolidate the official party was a contradiction in terms because, in the final analysis, the military seemed to be trying to strengthen a mechanism for which it did not have much use in the first place. Its desire may have been, at bottom, for an official party that could win elections without fraud, but certainly no more than this.

The search for alternatives did not last long. The decision to resurrect the official party was announced on 2 September 1961, and the directorio scheduled elections for a constituent assembly for 17 December. Reacting to this sudden call, the PDC, the PAR, and the PSD formed a united front, the Unión de Partidos Democráticos (UPD), to contest the election. The candidates of the official party, now called the National Conciliation Party (PCN), campaigned on the record of the directorio and accused the UPD of “reaction.” The PCN won the majority of the seats in the assembly by a margin of 37 to 17. The assembly quickly produced a somewhat altered version of the Constitution of 1950, declared an amnesty, and scheduled presidential elections for 29 April 1962. Rivera was nominated in February 1962, and he ran unopposed, since the opposition parties abstained.

Rivera did not want obstruction from an opposition entrenched in the legislature, and he made his peace with the oligarchy. He enjoyed favorable coffee prices and was able to follow a pragmatic and fairly progressive course, relaxing the electoral statute in 1964 and continuing with some reforms, which, however, always fell short of damaging the interests of the oligarchy. While Rivera was in power, the opportunities offered by the Central American Common Market enabled the industrial bourgeoisie to expand its economic base. Between 1953 and 1962 the number of corporations registered in El Salvador jumped from about 80 to 482, a sixfold increase.10 Between 1961 and 1965 the average annual variation of GDP was 6.9 percent, while average annual growth in value added by the manufacturing sector was 10.7 percent.11 Between 1960 and 1966 the value of industrial production went from $53.3 to $ 154.4 million.12 This was Rivera’s good fortune and not a result of planning.

But the relative success of the PCN under Rivera could not last. First, the Alliance for Progress collapsed eventually. In El Salvador this meant that tax reform and agrarian reform went nowhere, neither at that time nor later, and the progressive record of the PCN would yield increasingly diminishing returns, bringing back the old question of legitimacy.13 Second, Rivera could not pass his popularity on to his successor; nor could he guarantee that his relatively successful effort in building multiclass electoral support for the government party would continue. Third, the bourgeoisie remained in a relatively weak position with respect to the oligarchy.14 Fourth, the commodity cycle eventually brought back the phantoms of low prices, unrest, and renewed repression. And fifth and most important, the spurious openness of the system could be maintained only so long as no opposition party or coalition of parties could mount a successful challenge and force the PCN to alter election results or engineer a preventive coup.

The Elusive Electoral Game

It is difficult to determine whether the Christian Democratic Party (PDC) became the dominant party in El Salvador in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is unlikely that in the space of a decade a political party could build lasting bonds between itself and substantial sectors of the electorate. What is clear is that the PDC became the principal antagonist of the PCN and that its electoral success made it a threat to the Salvadoran military and the oligarchy. Their reaction to this perceived threat contributed to the collapse of the scheme of government that had prevailed since 1948.

Like most Christian Democratic parties of Latin America, the PDC grew out of the deliberations of a study group of Catholics from conservative backgrounds. Through their reading of papal encyclicals and their own observation of their society they became concerned about problems of social inequality and felt the need to articulate a political alternative between Left and Right. The study group began to meet in 1958, and the party was registered in 1960.

Initially, the PDC seems to have attracted conservatives disenchanted with the official party, as well as professionals and petit bourgeois elements who had been relatively inactive in politics. During the 1960s the party maintained a line of moderate reformism which may have caused alarm in certain circles but which, according to one critic, was really “neoliberal.”15 What was a matter of greater concern to the obstructionists in the oligarchy and in the armed forces was the party’s ability to organize and mobilize support. The PDC was able to enlarge its base in an essentially middle-class constituency to include lower- and working-class elements from the urban areas.16 Given that the parties of the Left were illegal, the PDC may have benefited from the support of voters whose preferred alternatives were not available.

The PDC is not likely to have benefited greatly, however, from the splintering and disintegration of other Salvadoran parties during the late 1960s and early 1970s. For example, the disintegration of the PAR could not have resulted in much additional support for the PDC. The conservative faction of the PAR left the party following a takeover by a younger and more radical faction led by Fabio Castillo, a member of the 1960 junta and a former university rector. In 1965 that conservative faction created the Partido Popular Salvadoreño (PPS), which sought to offer an electoral outlet for the weaker faction of the bourgeoisie. The new PAR was declared illegal in 1968, and most of its followers gravitated to Guillermo Ungo’s MNR (see Figure 3-1). Therefore, the growing electoral strength of the PDC must be attributed to the use of patronage to develop a political machine that engaged the support of the urban lower class.

Even though the PAR won the mayoralty of San Salvador in 1956, no opposition party has utilized that office—as well as other positions captured by the PDC through the election of 1972—with the efficacy displayed by José Napoleón Duarte during his tenure as mayor, 1964–70. Duarte created a powerful political machine based on Acción Comunitaria, a program of community self-help that organized residents on a neighborhood basis and tried to articulate their demands and serve their needs. Eventually, Acción Comunitaria became another department of the municipal administration. This record of service to the lower- and working-class residents of the city paid off handsomely on the two occasions on which Duarte ran for reelection and in his 1972 presidential campaign.

Support for the PDC also grew out of the logic of a competitive electoral process in which the strongest member of the opposition could present itself as a viable alternative, exploiting the shortcomings of military reformism. Armed with a record of service in the municipalities under its control—thirty-seven in 1964–66, eighty-three in 1966–68, and seventy-eight in 1968–70—and with the accomplishments of the independent session of the national Legislative Assembly in 1968–70, the Christian Democrats began to mount a more direct and effective challenge to the rule of the PCN. During that session of the assembly the PDC joined with MNR deputies, eight progressive deputies from the PCN, and one maverick from the PPS to form a majority. Committee rules were changed, drafts of progressive bills were reported quickly by the committees, and reformist legislation was passed. This was added cause for alarm among rightist elements, especially when President Fidel Sánchez Hernández (1967-72) attended the opening session of a congress on agrarian reform organized by the assembly and declared that agrarian reform was a necessity in El Salvador.17

In 1967 each opposition party had presented its own presidential candidate and the official candidate, Sánchez Hernández, had been elected with 54 percent of the vote. His election had not been tainted by blatant manipulation, and he was, therefore, able to extend some bridges to the progressives. But President Sánchez felt increasing pressure on his right flank. The growing strength of the PDC made matters worse, since he had to put some substance behind the nominal reformism of the military in order to compete with the PDC—which would incur the wrath of the oligarchy—or move quickly to turn aside the PDC challenge by other means. The 1969 war with Honduras gave Sánchez a respite by conferring on his administration an aura of legitimacy and forcing the opposition to adopt a low profile. This was a very temporary respite, however. The economic consequences of the war were very somber: the loss of a market of $23 million per year, the closing of land access to Costa Rica and Nicaragua, and the loss of a safety valve that allowed the export of surplus labor.

Even though he reached the accommodation with the oligarchy that all military presidents before him had found indispensable, relations between Sánchez and the conservative backers of the PCN were strained. The Right was alarmed by its legislative losses in 1968, unhappy that Sánchez interpreted the virtual sweep of the PCN in the elections of 1970 as an endorsement of his reformist policies, disturbed by the fact that Minister of Agriculture Enrique Alvarez, a “black sheep” of one of the fourteen families, had formed a committee to study the question of agrarian reform in 1969, and enraged by the introduction of draft legislation concerning irrigation, drainage, and the use of marginal lands. It was most unhappy that Sánchez had, in September 1970, put himself behind these initiatives and actually signed the bill into law in November.

The conservatives were able to thwart the implementation of the irrigation and drainage law, unleashing a vociferous campaign of agitation through the media, which got worse when the government announced its intention to organize agricultural workers. The continuing decline in coffee prices put the planters in an even more belligerent mood, but they failed in their not too subtle effort to provoke a confrontation between President Sánchez and his colleagues in the armed forces. These events convinced the conservatives that they would be better served by their own candidate, one whom they could support and who would stop the dangerous experiments in the agricultural sector. They found it in General José Alberto (Chele) Medrano, who had been dismissed as commander of the national guard in December 1970 amid rumors that he was plotting against the government.

The severe losses that they suffered in the 1970 assembly race had a sobering effect on the opposition parties, and in September 1971 they formed an opposition coalition, the Unión Nacional Opositora (UNO), which included the PDC, the MNR, and the Unión Democrática Nacionalista (UDN). Like the PDC, the Movimiento Nacional Revolucionario (MNR) also grew out of a study group that met during 1956-58. The MNR was not very successful as a party, however, for its platform was highly intellectualized and relatively abstract. Led by Guillermo Ungo, the son of a founder of the PDC, the MNR gradually built a following among the workers in large industrial enterprises, and while it stayed on the Left, it showed a marked tendency to collaborate with Social Democratic and Christian Democratic initiatives. Rafael Glower Valdivieso, a former economy minister under Sánchez, also joined the MNR. The party received the vice-presidential slot on the UNOticket and filled it with Ungo.

The UDN presented itself for the first time in 1970 as an electoral vehicle for Francisco Lima, a former vice-president of the republic and ambassador-at-large to the United States, Canada, and the OAS. Lima was another PCN maverick who had resigned his post in protest over President Rivera’s insensi-tivity to the poor. Lima tried to organize a “left” within the PCN. and was expelled from the organization, together with his brother Ramón.18 A splinter of the official party and supported by junior army officers, the UDN was under constant pressure from the government. Both the UDN and the MNR agreed to support the presidential candidacy of José Napoleón Duarte.

Sensing some potential gains if it tried to capture some of the disaffected PCN conservatives, the PPS stood aloof from the UNO coalition and presented its own presidential candidate. José Rodríguez Porth, a lawyer and member of the oligarchy who had resigned from the 1961 directorio in protest over Rivera’s reformism, had volunteered his services to prosecute the kidnappers of Ernesto Regalado Dueñas and generally represented management in labor disputes. The PPS, therefore, had great affinity with PCN conservatives. It received financial support from the oligarchy; it was—to say the least—very receptive to business demands; and it played around with terms like “silent majority,” “law and order,” and a host of others that were appropriate if one wished to attract conservative backing. But the PPS was not, after all, the most ideal vehicle for the more reactionary element of the Salvadoran oligarchy to vent its fury in the election of 1972. The leadership of the PPS was composed primarily of elements from the industrial bourgeoisie, and the conservatives wanted a more symbolic figure.

Their candidate, Chele Medrano, a hero of the war with Honduras and former commander of the national guard, had organized a Frente Unido Democrático Independiente (FUDI) in early 1971. According to Webre, FUDI was a conservative splinter of the PCN and an outlet for “landowner discontent with the government’s coffee policy as well as its position on agrarian reform and its ‘softline’ approach to normalization of relations with Honduras. The FUDI appears to have drawn its leadership from the landed elite of the country’s western zone, especially the powerful Salaverría family of Ahua-chapán which until its defection in 1971 dominated the PCN party hierarchy in that department.”19 The connection between a former commander of the guard, reactionary oligarchs, and right-wing paramilitary groups was not coincidental; nor was it confined to the electoral campaign of 1971-72.

Medrano was neither a civilian ultraconservative like Rodriguez Porth nor an astute traditional liberal like Miguel Ydígoras of Guatemala. Medrano was the man who had pacified labor in 1966-68, a man who understood the operation of the political economy of export agriculture in El Salvador, a man who understood why it was necessary to keep labor organizers out of the Salvadoran countryside, and a man who could take initiative during times of crisis. Quite literally, he represented an opportunity to return to the golden past when Salvadoran presidents did not have to talk about reformism, when junior officers were easily put in their place, and when there was no need to appease so many professionals and intellectuals who, the conservatives insisted had never met a payroll in their lives, did not know how to read a balance sheet, and did not understand how Salvadoran society “worked.” The implication was that Medrano would rule through an unadorned state of exception, that is, one above the law, without opposition parties, without labor unions, and without interest groups except those representing the oligarchy.

Hemorrhaging from a substantial loss of conservative support, confronted by a coalition of moderates and progressives with a common presidential candidate who could very likely win the popular vote, and unable to emphasize its moderate reforms to attract middle-class support, the PCN was very likely to lose the 1972 election. The campaign was bitter and full of mutual recrimination. Early totals from outlying areas had Colonel Arturo A. Molina, the PCN presidential candidate, ahead with 54 percent of the vote, but as returns from the urban areas started to pour in, the UNO closed the gap and apparently went ahead. The government stopped announcing partial results and declared its candidate the winner the day after the election—21 February 1972. The opposition protested the outcome and released its own figures of the final result (see Table 3-1 for the contrast between the government’s and the opposition versions). Duarte and Ungo announced that they would challenge the election and organize a general strike if necessary.

On 25 February a hastily convened Legislative Assembly elected Molina, who had only obtained a plurality of the vote, over the objections of opposition deputies, who walked off in protest. The UNO then asked voters to deface their ballots in the upcoming legislative assembly election of 12 March. This paid off in San Salvador, where the number of null votes from defaced ballots exceeded the combined total for the PCN and the PPS. Under Salvadoran law the election had to be nullified, and the departmental electoral board ordered a new election on 22 March. The atmosphere remained very tense.20

It is difficult to determine the ideological orientation of the officers who staged the army rebellion of 25 March 1972. The revolt sprang from the artillery barracks of El Zapote and the San Carlos garrison. Apparently, the extreme Right was not involved. Colonel Benjamín Mejía led the revolt, and he sought the support of moderate leftists and the Christian Democrats. Glower Valdivieso and Duarte took turns in radio broadcasts to urge the country to support the rebellion. No mass appeal was made to take arms, and apparently no effort was made to distribute them, although Duarte urged his supporters to obstruct the advance of government forces. The revolt was put down by loyal units from outside the capital, the national guard, and the air force.21

The elections of 1972 and the military revolt represent a drastic discontinuity in the operation of the Salvadoran model of one-party domination. The system intended to maintain the domination of the armed forces in an alliance with the more significant economic groups of the country. The original blueprint excluded the possibility of defeat and assumed that the official party would be able gradually to include the more dynamic sectors of the middle class. The latter evolved their own independent mechanisms of political organization, however, and remained aloof, but their ability to participate in elections and share in the control of some sectors of the government, albeit in limited form, did create the incentives for continued participation and neutralize the more radical segments of the opposition.

The figure and actions of the main loser in the 1972 fiasco, Duarte, illustrate some of the unwritten rules of the pattern of government that was crumbling at the time. Although supported by one military faction, which came out against the fraud by force of arms, Duarte refused to try to mobilize his supporters. He may have refrained from a direct appeal to the masses for fear of turning military opinion against him and his party; given the treatment that both received after the rebellion was suffocated, it is hard to imagine how a more decisive stance would have brought them greater disgrace. On the other hand, despite his populist tactics and his progressive policies as mayor of San Salvador, Duarte may have been a practitioner of the game of controlled democracy which excluded direct appeals to the masses. Therefore, his fear of revolution or civil war may have been stronger than his fear of certain retribution.

But, after all, Duarte was not the only loser in 1972. President Fidel Sánchez was in a position somewhat similar to that in which Lemus had found himself twelve years before, and he was passing the government on to his successor under very difficult circumstances. Whatever claim the PRUD-PCN may have laid to a social democratic or reformist orientation effectively ended at that time. The equilibrium of forces within the party was upset, the chances for “reform” were compromised, and the linchpin that had held the system together all along, the “pacified countryside,” was about to come loose. Duarte and the reformists may have been hoping all along that, as they had done elsewhere in Latin America, the armed forces would eventually resign themselves to a civilian president elected by a popular vote. But they did not.

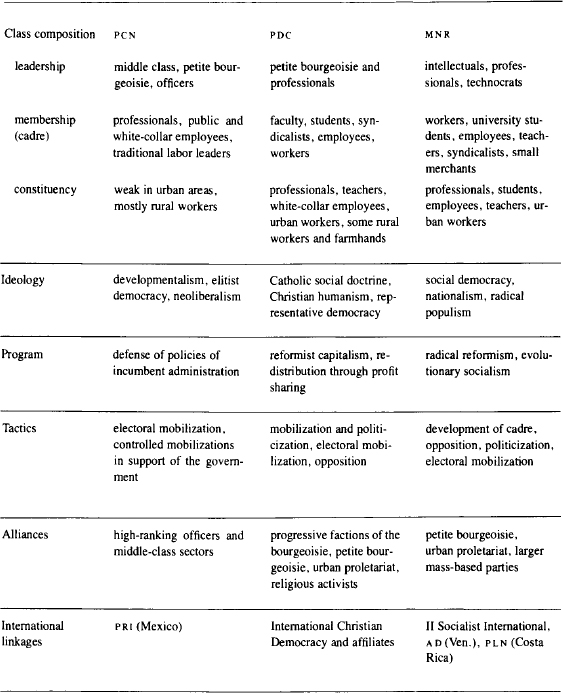

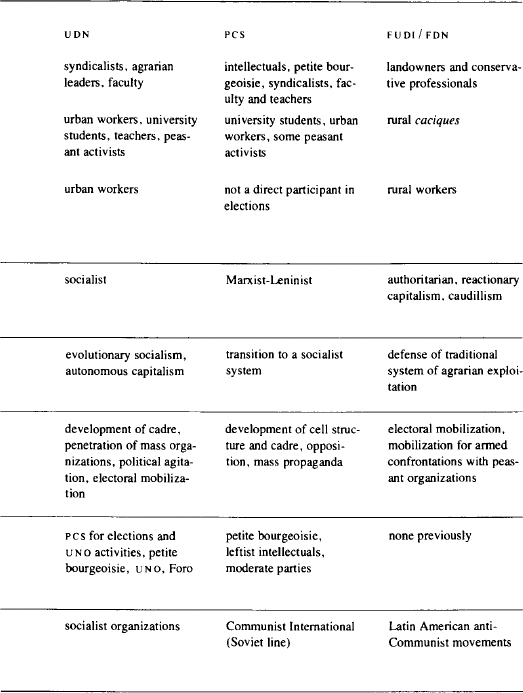

As is usually the case when examining authoritarian situations, it is difficult to gauge the true alignment of forces and the real strength of each actor, but the summary included here prepared by López Vallecillos describing the salient characteristics of the more prominent actors in the Salvadoran system of parties is probably an accurate portrayal of the situation in 1972, and perhaps as late as 1977 (see Figure 3-2).

The political defeat of the moderates in 1972 compromised reformism and destroyed the new center emerging in Salvadoran politics, leaving a radical situation with two basic characteristics. One was the disappearance of political intermediaries between the government and major social groups and classes; the other was the more direct confrontation between the latter and a military increasingly unable to manage social conflict peacefully.

With their electoral options preempted by systematic fraud, opposition political parties could make only token participatory attempts in elections that were increasingly meaningless. Their main purpose was no longer to try to reach power through elections but to demonstrate the dictatorial nature of the government. This diminished their relevance and sent them into a tailspin of disorganization and internal debate, from which they have yet to recover. Lacking effective avenues to represent their interests and given the military’s attempt to “depoliticize” the society, the more progressive sectors of the bourgeoisie and the lower and popular classes had to find different political roles. Social organizations filled the vacuum of partisan activity for the latter, while middle-class elites went into inactivity or began to contemplate more drastic alternatives. The Catholic hierarchy and lay organizations became increasingly militant and critical and began to confront the government with the results of its repression—such as the peasant massacre of La Cayetana in November 1974 and the student massacre of July 1975—and to articulate the demands of the lower and popular classes.

FIGURE 3-2

Characteristics of Salvadoran Political Parties

Source: López Vallecillos, “Fuerzas Sociales,” pp. 568-69, 578-79

The role of student, peasant, and worker organizations became more important, as they started to collaborate with each other, to organize protest demonstrations, takeovers, and sit-ins, and to engage in civil disobedience in order to make their demands heard and to defend themselves from increasing attacks by the paramilitary Right. This last, meanwhile, was becoming a very effective vehicle for the expression of oligarchic dissatisfaction with the status quo. This polarization mirrored the developing confrontation between the oligarchy and the church and other civic organizations, at the elite level, and between the right-wing paramilitary groups and popular organizations like the Bloque Popular Revolucionario (BPR), created in 1975; the Frente de Acción Popular Unificada (FAPU), created in 1974; the Federación Cristiana de Campesinos Salvadoreños (FECCAS); and the Unión de Trabajadores Campestres (UTC). Urban terrorism, clashes between these rival groups in the countryside, and assassinations of priests, popular leaders, and oligarchy figures became frequent. Finally, the vía armada became a more realistic option, and insurgent groups, which had been operating intermittently, became larger, better organized, and more capable of becoming the opposition.

The military believed that it could continue to operate in these new conditions with only minor alterations in its basic formula of domination. It assumed that the opposition would eventually calm down, that some concessions would be forthcoming from the oligarchy, and that its own version of reformism would carry the day. It was wrong on all counts.

The opposition became more defiant and effective. The Right reacted with more violence. The oligarchy clung to its narrow and selfish version of free enterprise. And the Salvadoran military’s version of the old Porfirian scheme (pan o palos [bread or the stick]), repressive reformism, became simply repression. In the words of José Simán, a Catholic intellectual and a progressive member of the bourgeoisie, “A horizon of death came to replace the horizon of life.”22