Chapter 8

Illusion and Reality

The Salvadoran Election of 1982

The principals in the Salvadoran transition entered the constituent assembly election of 28 March 1982 with very different expectations. The Right had initially opposed the election. As the date of the election approached, however, the Salvadoran private sector began to perceive it as an opportunity to remove Duarte and the Christian Democrats from the government once and for all. The disloyal element in the Salvadoran Right wanted to go much further; for them the election represented a chance to restore the system of reactionary despotism. Major Roberto D’Aubuisson became the leader of this effort. The always malleable PCN, which many observers had discounted as a serious contender, prepared quietly, trying to bring its machinery into gear, make a good showing, and offer itself as a partner in a rightist coalition. The Christian Democrats, who had floated the idea of the election in December 1980 out of desperation, saw their fortunes decline and began to explore the possibility of a coalition. The FDR, which could not realistically participate, assumed that the election would be but another exclusionist fraud, while the guerrillas hoped and made efforts to insure that people would stay home on election day.

The more prominent foreign actors involved in the transition—the Socialist International (SI), the Venezuelan government, and the Reagan administration—had their own goals and apprehensions. The si found itself in the uncomfortable position of having to denounce the election, since its FDR allies had been left out. Both redoubled their efforts to launch a negotiated settlement, but the drive for the election had too much momentum. The Venezuelan Christian Democrats, who had supported Duarte all along, did their best to improve and assist in the planning of the election, which employed a ballot and a system of proportional representation very similar to Venezuela’s. They hoped that the election would vindicate their besieged coreligionaries and offer them a respite. Finally, the Reagan administration wanted to use the election to weaken and isolate the Left, to discredit the guerrillas, to produce a government that could be presented as legitimate and worthy of continued support, and, possibly, to force the Christian Democrats to form a coalition with one of the parties representing the private sector in order to diminish the strife between the two.

None of these actors had its expectations met fully or its hopes dashed completely. In the short run the disloyal Right profited the most from the outcome of the election, while the guerrillas were probably the biggest losers. The Christian Democrats won the election, but they lost power. The military and the Reagan administration finally had a “popularly elected government” to work with, but a government dominated by the element that could provoke Congress to rescind aid. The FDR proved that its presence was important in any overall settlement in order to prevent the Christian Democrats’ being overwhelmed by the Right. In essence, the election was genuine, but it did not break the stalemate. Nor did it produce an alignment which put the obstructionists at a disadvantage. The election was an important watershed; it helped give an idea of the relative strength of the different contenders, but it did not solve the major questions of the transition.

The Integrity of the Election

Most observers of the Salvadoran election, including this writer, and most representatives of the international media covering the event agreed that the election was genuine.1 The election offered a limited but real choice; there was some latent and some overt intimidation, but it did not come from a single source; the proceedings were reasonably orderly; and the votes were counted without manipulation.

There can be little doubt that the election presented Salvadorans with a clear-cut choice, despite the absence of the FDR. The fact that the Salvadoran electorate recognized the salience of that choice may be seen in the division of the bulk of the votes between the PDC and the ARENA. Seven out of every ten valid votes went to these two contenders. No other party or group of candidates came close to these two; nor were their campaign messages and platforms as clear and unambiguous as those of the PDC and ARENA.

Roberto D’Aubuisson was the most forceful and visible campaigner. He toured the country incessantly and visited every department twice. His message was straightforward: defeat the guerrillas by escalation and roll back the socioeconomic reforms.2 His coffers were brimming, and he had no problem buying considerable space in the local press, ARENA retained a Salvadoran affiliate of the McCann Erickson advertising firm, adding a touch of Americana to the major’s campaign. On election eve ARENA headquarters was a beehive of activity, a combination armed camp and middle-class enclave.3 The mood was festive, even though the building had been attacked scarcely a month before.4 Many of the campaign volunteers and poll watchers receiving their instructions for the election spoke English and were very cordial. The place could have passed for the campaign headquarters of any candidate in a U.S. election except that many persons wore sidearms and armed guards were everywhere.

Professor Thomas Anderson and this writer had the opportunity to talk at some length with Ing. Mario Emilio Redaelli, director of control for the campaign and secretary general of ARENA. Redaelli’s father was tortured and killed during the peasant revolt of 1932; Radaelli was eight months old at the time. Although an amiable host, Redaelli did not hide his anti-Communism and his animosity toward the Christian Democrats. He showed us a letter, presumably written by pes Secretary General Shafik Handal, which demonstrated that Adolfo Rey Prendes, until recently the mayor of San Salvador and the head of the PDC ticket to the constitutent assembly, and Ovidio Hernández, the PDC minister of the interior, were actually members of the pes. Redaelli believed that the PDC’S call to postpone the election was an attempt to avoid defeat, and that the Christian Democrats were embarked on a series of maneuvers to steal the elections.5 In addition, he complained that the Ley Electoral Transitoria of January 1982 had failed to incorporate any of the proposals submitted by the five opposition parties and that it gave an unfair advantage to the PDC. Redaelli was not prepared to tell us what ARENA would do in case of a fraud, but he stated that a second-place finish for his party would not necessarily be a result of government fraud.6

The ideological and social distance between ARENA and the PDC was, to say the least, considerable. The campaign messages of ARENA focused on the shortcomings of the Christian Democrats, whom they blamed for the country’s poor economic condition and for the placing of too many restraints on the Armed Force. These messages were reinforced by those of the PCN, which sought, among other things, to depict PDC leaders as embezzlers and common thieves.7 The PDC’S main contender was ARENA, however, and that party was receiving the support of the disloyal Right.

By contrast, the campaign of the PDC was relatively subdued. The advantage of incumbency was diluted by a provision in the Ley Transitoria barring public officials from campaigning. This limited the leadership of the PDC to a series of major addresses in which it delivered the party’s message. The PDC was vulnerable in two areas: the deterioration of the economy and the still-unresolved question of uncontrolled government violence.

Duarte addressed the nation by radio and television on 20 January 1982. He defended the party’s record in office, arguing that the PDC had tried to manage a process of transition from dictatorship to democracy while under continuous threat from extremists. He further stated that the party was pursuing reasonable economic policies and that the electoral solution was the only alternative to violence. Defending the PDC covenant with the Armed Force, which he said sought to improve the military institution and bring it closer to the people, he reiterated his charge that rightist extremists in the Chamber of Commerce, the ANEP, the AP, and other private sector organizations were trying to destroy the possibility of democracy and to prevent Salvadorans from achieving social justice.8

On 24 January, Planning Minister Atilio Viéytez delivered a rebuttal to a document prepared by the Chamber of Commerce of El Salvador. Following a discussion of the performance of the different sectors of the economy during 1981, Viéytez pointed out that the chamber had omitted two crucial points in its document: the flight of almost 3 billion colones since 1979 and the depressed export prices for cotton, sugar, and coffee.9

The defense of the government’s economic record was coupled with an attack on the elements that were trying to restore El Salvador to pre-1979 conditions. Without mentioning D’Aubuisson or ARENA, many campaign messages of the PDC depicted the party as the best alternative to extremism, and as the most decided supporter of peace. In its final message the PDC warned the electorate that a vote for the rightist parties would be a vote for injustice, inequality, authoritarianism, oppression, fraud, and corruption. In essence, then, Salvadorans had a clear-cut choice between the anti-Communist, hard-line, and laissez-faire approach of ARENA and the reformist, incremental, and communitarian approach of the PDC.10

Concerning the question of intimidation, Duarte and the Christian Democrats insisted all along that the election would be fair. The Armed Force, for its part, proclaimed that it would guarantee and respect the result, as well as the safety of the voters on election day.11 There was intimidation during the campaign, however, as well as acts of violence related to it. D’Aubuisson was shot at on 27 February and wounded slightly. Rafael Rodríguez González, a high-ranking official of the PCN, was murdered by unknown assailants. Labor Minister Julio Samayoa, who served as campaign coordinator for the PDC, was fired upon. On 17 March four Dutch journalists who were trying to make contact with a guerrilla unit were assassinated.12 Threatening phone calls were received by journalists covering the election.13 A series of banners appeared around San Salvador asking journalists to “tell the truth.” By election day, though, the contingent of foreign journalists was so massive that no further threats were reported, and in general correspondents had free access to polling stations and no official interference in their attempts to contact the guerrillas.

The most obvious form of intimidation, of course, was the compulsory requirement to vote. Following Salvadoran custom, as well as the practice of many other Latin American countries, the Ley Electoral Transitoria of January 1982 made voting compulsory. The rate of voter turnout has always been relatively high in El Salvador, even in meaningless elections. Therefore, there is something akin to a habit of voting in El Salvador, if only to stay out of trouble with the government. In some elections public employees had their checks withheld until they established that they had voted; apparently, this was also the case in 1982. Official penalties for nonvoting were set by the election law at between 2 and 50 colones, except in cases of indigence, in which the fine could not exceed 2 colones.14 Moreover, since the guerrillas urged a boycott of the elections, nonvoting could be interpreted as proof of guerrilla sympathies and expose one to the worst kind of retribution. In short, many voters may have gone to the polls on 28 March simply to avoid possible repercussions.

The particular method that the government used to enforce compulsory voting—and to prevent multiple voting—makes it hard to judge how much these threatened sanctions influenced voter turnout. Article 36 of the election law mandated that the right thumb of every voter be impregnated with “very visible and indelible ink.”15 This was changed by Decree No. 966 of 5 February 1982 to read “invisible and indelible ink,” purportedly to assuage fears of retribution from the guerrillas. Special lamps were to be used to check for this mark. Article 100 of the law prescribed that the seal of the municipality be stamped on the cédula (individual identification card) of every voter.16 In the ten days following the election government officials could request to see the cards in order to enforce the law and assess penalties.

The Consejo Central de Elecciones (CCE) printed illustrated descriptions of the eight different steps required to cast a vote in all the newspapers on the days preceding the election, asking that the juntas receptoras de votos, that is, the officials and party representatives posted at every voting table, display these instructions where voters could see them.17 The one discrepancy between these printed instructions and the procedure established by article 100 was precisely the stamping of the municipal seal on the cédula. Whatever the reason for this omission, its effect may have been to lead some citizens to believe that their cédulas would not be stamped. This confusion may have affected the likelihood of voting for some, but this is difficult to assess, for it is doubtful that all of the voters fully understood the whole complicated process.

The fact remains, however, that this form of official coercion affected only the likelihood of voting and not the preference of the voter, since there was no way to check how the vote was cast.18 Given the format of the ballot (see Figure 8-1), which was practically identical to that used in recent Venezuelan elections, anyone, even in the crowded and cramped conditions observed by the author at most polling stations that he visited on election day, could have simply invalidated the ballot or left it blank. According to official figures, close to 9 percent of the voters invalidated their ballots and an additional 3 percent left them blank. Even though one must be careful in interpreting the meaning of null and blank voting in Latin American elections, about 12 percent of the voters refused to express any preference or could not express their preference on election day.19 Finally, an untold and difficult to measure, yet nevertheless large, number of Salvadorans simply did not vote.

FIGURE 8-1

Ballot Utilized in the Salvadoran Constituent Assembly Election of 28 March 1982

The evidence available and the pattern of events preceding the elections suggest that most of the intimidation affected turnout and not preference. The massive foreign presence, the presence of party representatives in every junta, and the absence of major complaints of systematic fraud from any of the participants suggest that the votes were counted as cast.20

The FDR condemned the election as exclusionist and unrepresentative. FDR officials continued to seek negotiations, however, while the guerrillas intensified their military operations.21 During the campaign the guerrillas managed to attract attention to themselves with a series of attacks, including the one against the Ilopango airbase in late January and numerous engagements with the army. In late February, guerrilla leader Roberto Roca vowed that the guerrillas would intensify their military effort and that this just happened to coincide with the election.22 A series of major battles were fought in late February around the Guazapa volcano and in Santa Ana, San Miguel, and San Vicente in early March. In the days prior to the election the guerrillas attacked the CCE headquarters in San Salvador and engaged in a campaign to destroy public transportation vehicles.23 On election day the owners of many of these vehicles kept them out of circulation, transportation came to a virtual standstill, and most people had to walk a few kilometers in order to vote. During that day small guerrilla units engaged in firefights with Salvadoran army and national guard units in the vicinity of polling stations, delaying the election in those places by several hours. This was the case in Apopa, in San Antonio Abad, where twelve guerrillas were killed, in San Francisco Gotera, and in a score of other towns.24 In Usulután a four-day battle for control of the departmental capital prevented the election from taking place at all.25 Although the guerrillas, to my knowledge, never fired upon would-be voters, their strategy was clearly to disrupt the elections and remind everyone that the country was still in the throes of civil war.

In an effort to manage the security problem the CCE kept the number of puestos de votación (polling stations) small, so that the army, the national guard, and the police would not have to spread themselves too thin. For the whole country there were 298 puestos housing 4,556 juntas receptoras de votos. In San Salvador, a city of 750,000, there were 500 juntas, but these were clustered in only 13 puestos.26 Although this was a vast improvement over the 1977 election, when residents of the capital could vote at only one polling place, it practically guaranteed long lines at every polling station. While this inconvenienced the voters, it was a public relations coup for the government: by mid-afternoon the lines were still long, and the international media called the turnout “massive.” The long lines may have also helped to forestall the possibility of a person voting more than once. As election day wore on, in fact, the concern was with whether everyone in line would be able to vote, especially in areas without electricity, where the polls were supposed to close down by 4:00 P.M. There is no way of estimating how many people went home without voting or how many juntas sought and obtained permission to extend the deadline past 6:00 P.M.27

Thus, under the circumstances, the election went well and many more people than anticipated did vote.28 Given the polarization of opinion about the Salvadoran process in the United States and elsewhere, however, others may utilize the details of this description to draw different conclusions.29 An incident witnessed by the author during a tour of parts of the country on election day may help validate my interpretation of what most Salvadorans were trying to do with their votes on that day.

Professor Thomas Anderson and this writer observed the Salvadoran campaign during 24-29 March. Not being official observers, we circulated very much on our own and followed our own agenda. On election morning we accompanied correspondent Stephen Kinzer and free-lance photographer Barry Allen in what was going to be a trip along the Troncal del Norte highway, from Apopa, a small town northeast of San Salvador, through Chalatenango. In general this area is not very sympathetic to the government or to the Right. It includes the “Indian country” around the Guazapa volcano, Suchitoto and its environs, where the popular organizations had been very strong, and the town of Aguilares, where Father Rutilio Grande was murdered. Voting in the area would serve as a good barometer of how seriously the election was being taken by the people.30

At 7:00 A.M. the streets around the center of Apopa were deserted, as patrols of the army and the national guard tried to drive a band of muchachos or subversivos, as the guerrillas are called by the people and by the security forces, respectively, from the area between the town square and the Vicente Acosta school, the polling station for the municipality. The guerrillas were trying to delay and obstruct the election. The military was trying to drive them out, but looked very disorganized. After we had been in the area for about a half hour, a sergeant came into the plaza and shouted that the way was clear. This is when we saw the Salvadoran election come alive, as people began to appear from everywhere and to walk toward the school. Many were in their Sunday best. Most were in good spirits. Our presence intrigued them, and their questions enabled us to ask some of our own during the hour that it took us to negotiate the three blocks between the town square and the school.

We were especially intrigued by the number of young males in the crowd. One tends to think of the members of this group as guerrillas, army conscripts, or disappeared persons. Yet they were very much in evidence and provided most of the entertainment during lulls in the shooting.

It was difficult to believe that these people were braving a firefight because they feared a greater evil. Most of the people that we talked to in Apopa went to vote not for the políticos but for themselves.31 They were quite realistic about the limited efficacy of the election, but they saw it as the only way they could endorse a peaceful solution to their crises: missing relatives, violent incidents, uncertainty, harsh economic conditions, and death. Most Salvadorans interviewed during that day said that they hoped that, somehow, the election would help to stop the killing.32

Regardless of one’s fantasies about El Salvador, to dismiss the hardships that hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans endured in order to cast their votes is to deprive them of their own meaning. Perhaps it is possible to argue that to “violent Central Americans,” elections do not mean anything or that many of them have been deprived of their basic human rights for so long that they could not possibly take elections seriously. But to use these arguments to ignore what the Salvadorans themselves tried to say on 28 March 1982 is no longer an attempt to understand but, instead, a dogmatic and self-serving exercise. To be sure, their statement may have been diluted by subsequent events, but the power grab of the Right and the exclusion of the Left should not obscure the fact that, first and foremost, Salvadorans voted for an end to their conflict. They came out to vote in a much larger number than anticipated primarily because they wanted to make use of this massive action to urge an end to violence and civil war. This transcended the real choice between Duarte and D’Aubuisson and constitutes the most important message delivered that day.

The Results of the Election

The rightist power grab following the election and the presence of the disloyal Right in the new Salvadoran government, has created the impression that the Right won the latest Salvadoran election, but this was not the case. First, in their head-to-head competition the Christian Democrats beat ARENA. Second, despite the opposition’s invective and its vitriolic attacks on the PDC, only ARENA emerged from this election as a party that can represent the disloyal Right in El Salvador. The others are too minuscule, like the PPS and the POP; are loyal to the democratic system, like the AD; or are simply parties that do not really follow ideologies, but instead, leaders and orders, like the PCN.

The election established the PDC as the foremost political force among the parties that participated in the election. This fact has been forgotten in the confusion that followed the election, when it became evident that the PDC could not form a coalition, but it is a vitally important piece of information. Despite having to campaign on a less than favorable record on the economic and human rights questions, the party won a plurality of the vote nationally, and in ten of the fourteen departments. Nationally, the PDC got 35 percent of the total vote and 40 percent of the valid vote, while ARENA got about 26 and 29 percent, respectively. (A summary of the election’s results is presented in Table 8-1.)

It is difficult to estimate how much the PDC benefited from votes that would have gone to the parties included in the FDR. Given the current level of animosity between frentistas and democristianos, however, it is doubtful that many potential FDR votes wound up on the PDC column.

It is also difficult to estimate the causal factors behind the PDC plurality, at least on a departmental basis. Looking at the compilation of returns by department in Table 8-2, it becomes apparent that guerrilla activity does not provide a good explanation of the vote. The PDC did both very well—Chalatenango and Morazán—and very poorly—Cabanas—in the areas of the most intense guerrilla activity during the last two years. But it did very well, coming in first, in departments with very recent intense guerrilla activity—Santa Ana, San Miguel, and San Vicente.

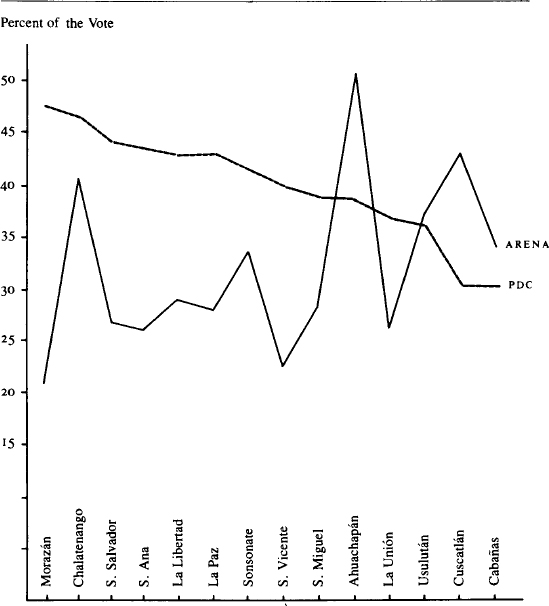

Another possible influence on the strength of the PDC vote is the facts of socioeconomic reforms. How well did the PDC do in areas where the Agrarian Reform has been a reality, primarily the western region of the country?33 Comparing the data presented in Table 8-3, which documents the extent of phase 1 of the reform shortly before the election, with the departmental voting returns presented in Table 8-2, it becomes evident that this does not provide a much better explanation of the PDC vote. Essentially, we find that, once again, the PDC vote fluctuates wildly in relation to the explanatory factor under scrutiny.34 For example, if we look at the returns and order the departments by percentage of the vote for the PDC—as done in a descending order in Figure 8-2, we find that Morazán and Chalatenango, departments where the PDC obtained its largest pluralities, there were, respectively, only two and nine cooperatives. In addition, 30 percent of the area under Phase 1 in Chalatenango had been abandoned by the time of the election. By contrast, the number of cooperatives was also low in the departments where the PDC did worst, Cuscatlán and Cabanas, with two cooperatives each. Of course this does not deny the significance of the agrarian question in the present Salvadoran crisis. As a matter of fact, this theme provided one of the issues which fueled the campaign. But it does indicate that one single aspect of this question cannot explain the fortunes of a party that has tried to address it during the last two years in the middle of a civil war. Such factors as landowner resistance, level of violence related to the reform, degree of cooperation from local military and government officials, and guerrilla presence must also be considered, and, unfortunately, not all of those data are available, on a systematic basis, at the departmental level.

Perhaps the neatest explanation of PDC and ARENA strength at the departmental level is given by a geographic cleavage of sorts, which reflects a geographical specialization of agricultural labor, dividing the country into the “old coffee” departments of the west and the rest, ARENA did well in the “old coffee” departments of Ahuachapán, Chalatenango, Sonsonate, and Cuscatlán. This differentiation had considerable political significance at the time of the election of 1982, since one of the issues of the election was precisely whether or not Decree No. 207, “Land to the Tiller,” was going to affect lands dedicated to other agricultural crops. Opposition to this was the centerpiece of the campaign of the agrarian front and, incidentally, the first issue that the majority coalition in the assembly took up in its bid to reverse the reforms of the Christian Democratic juntas.35

The election also established ARENA as the vehicle of the reactionary coalition and as the most important element in the Salvadoran Right, ARENA ran well, much better than expected, but it captured only four departments: Usulután, Cuscatlán, Ahuachapán, and Cabanas. Despite its intense competition with the PDC, the fortunes of ARENA were not influenced solely by the strength of the PDC in the different departments. As Figure 8-2 shows, the ARENA vote at the departmental level does not increase gradually with the decline of the PDC vote but fluctuates on its own. This reflects not only the presence of the PCN as a third force, influencing the overall distribution of the vote, but also the local blend of the factors mentioned above that relate to the land question and to the level of violence. However, the ARENA strength should not be interpreted as a direct result of intimidation. One should not ignore the impact of fifty years of anti-Communist propaganda, the low educational level of the population, and the fact that the guerrillas have also killed people, ARENA may or may not be able to preserve this level of support, but its showing in 1982 suggests that there is a sizable segment of the population that identifies with the hard-line stance of Roberto D Aubuisson and with the intransigence displayed by ARENA ever since its inception.

It is difficult to gauge what lies behind the results involving the other parties. For example, it is likely that the PCN lost its most reactionary element to ARENA. Similar splits have affected the PCN in the past and, this time, those who left had much greater intensity about the issues and a more specific focus. What was left of the PCN was probably its traditional rural constituency and a political machine dating back to its “official” days which includes some labor, middle-class, and bureaucratic elements. The PCN continues to look to the military for guidance, and since the distance between the military institution and the reactionary coalition has increased, not only since 15 October 1979 but, more important, since the ISTA crisis of 1976, ARENA and the PCN may have trouble working together. The military brass is also distrustful of D’Aubuisson and very concerned about how the actions of the former major and his party may affect United States military aid. The 1982 constituency of the PCN and its relation with the military may make the ARENA-PCN coalition unstable, and they may not have much in common beyond their anti-Communism and a common hatred for the PDC.36 Finally, the PCN retains a somewhat more pragmatic outlook than does ARENA, and although basically a conservative party, it is not as ideological or as impassioned as ARENA.

FIGURE 8-2

Approximate Distribution of the Vote for the PDC and ARENA, by Department

Source: Computed from U.S. Department of State, Foreign Broadcast Information Service, VI, Central America, I Apr. 1982, pp. 1–2.

The Acción Democrática has democratic roots, since its principal leader, René Fortín Magaña, was a member of the junta of 1960. Despite its liberal economic outlook the AD does not appear to be reactionary, at least certainly not disloyal. The AD made its best showing in San Salvador (see Table 8-2) and managed to capture two seats in the assembly. This was somewhat less than had been anticipated. Apparently, the AD could have formed a government with the PDC had they captured a sufficient number of seats. At one point, it was reported that the party was prepared to join the PDC in the opposition if the Christian Democrats were excluded from the government after the election. The AD seems to be competing for the support of a constituency very similar to that of the PPS, which got only one seat in the assembly. As a result of this and of the good showing by ARENA, it is difficult to figure out how much of the industrial and commercial bourgeoisie supported the AD and the PPS and did not run after ARENA. The PPS, however, is definitely more conservative than the AD, at least at the level of the leadership. Chele Medrano’s Party of Popular Orientation (POP), which is basically the FUDI of the 1970s, was no longer so attractive to the agrarian front, which now had ARENA, and as a result the POP got not even one seat in the assembly.

A final reflection on the results of the election concerns those who were not represented in it: the MNR, the MPSC, and the other Social Democratic parties included in the FDR. The MNR ran in coalition with the PDC in 1972 and 1977, and the MPSC is a splinter of the latter. Thus it had been unclear how much of its original constituency the PDC had been able to retain. The 1982 election clarified this, suggesting that the PDC had held its constituency in the urban middle and lower classes and had attracted peasant support through the UCS. This does not mean, however, that the FDR has no support.

One may engage in speculation about how large that support actually is. Since the PDC does not have majority support, the FDR parties have a tremendously significant role to play not only as the representative of the Left in possible future elections but also as the most compatible partner for the PDC in any future attempts to set up a center-left government. The PDC needs the support of the parties included in the FDR to counterbalance the Right. Had these parties been able to participate in the 1982 election, the outcome would have been very different. As a matter of fact, that participation would have been the acid test of whether the United States and the Salvadoran military were really interested in neutralizing the rightist obstructionists. As it was, the election was an important watershed, but it did not result in a neutralization of the obstructionists; nor did it strengthen the position of the aperturistas. Instead, the exclusion of the democratic Left indicates that the rightist obstructionists are still very much in command.

The Salvadoran Transition after the Election

The aftermath of the constituent assembly election of 28 March 1982 demonstrates that, during this first stage of the Salvadoran transition, the strongest actors have had what amounts to a veto power over the actions of their antagonists. Many other events of the transition could be mentioned to support this contention, but the outcome of the election illustrates the point well.

The outcome has been labeled “half a win,” “a bare cupboard,” “a return to the point of departure,” and a “Pyrrhic U.S. victory.”37 Yet none of the major actors has left the scene, even though the Reagan administration exaggerated the setback suffered by the guerrillas.38 The outcome of the election remained inconclusive in early June 1982. The process remained stalemated, and the key ingredient of a democratic resolution, the neutralization of antidemocratic obstructionists, remained but a distant possibility.

The Christian Democrats won the election, only to lose power. They finally showed off their leftist opposition in an election, only to discover that they will need the support of the Social Democrats if they want to form an effective government in the future. The disloyal Right put itself in office through the election, after two years of failed coup attempts, but its rising influence was held in check by the United States and the Salvadoran military. The United States finally had a government “elected by the people” in El Salvador but one controlled by a man described as a “pathological killer.” The military brass got the safe and uncomplicated election that it could tolerate at this time, but it also got an unwieldy arrangement and a militant faction in the new government whose proposed actions put it on a collision course with the U.S. Congress. In addition, the military institution must once again worry about the disruptive effects of middle-rank officers being courted by the disloyal Right, now in government. The guerrillas grabbed their share of headlines but their morale and prestige suffered considerably. The FDR did not participate in the election, and its absence contributed to an electoral outcome that makes a democratic resolution all the more difficult. In summary, each antagonist— and it is exceedingly important to emphasize that there are quite a number of these in El Salvador at the present time, and not just the “government” and the guerrillas—took and delivered some blows.

But there is a clue to this kaleidoscope. First, the present Salvadoran government has no better chance of moving toward democracy than did any of the juntas constituted since the October 1979 coup. The ideological heterogeneity of the government is tremendous, for it includes truly antagonistic actors. This government cannot move anywhere unless it sheds its pluralist pretense, and the more likely outcome will be the departure of the Christian Democrats who, sooner or later, will have to move to the opposition.

Second, the dominance of the disloyal Right in the assembly means that the increased domestic and international legitimacy that an elected government could have derived from the election will probably be wasted. It is clear that the disloyal Right intends to sabotage and reverse the modest achievements of the transition.39 In addition, its rise to power has served as a signal for a renewal of rightist violence. Forty-eight villagers were massacred by men dressed in army uniforms scarcely one month after the election, and three Christian Democratic mayors and nine other party activists have been killed since the election.40 Corpses of persons executed by death squads have reappeared in traditional drop-off areas around San Salvador.

Third, given the lack of acceptable alternatives, the Reagan administration will try to make this arrangement work. It has conditioned the continuation of aid on the existence of a coalition government.41 Despite the good intentions of Provisional President Alvaro Magaña, however, the new arrangement is not a government but a contraption, and all the power and prestige of the United States cannot make this contraption work for long in a manner acceptable to the American public and the Congress. In recognition of his official position the administration lifted the ban imposed in June 1980 on D’Aubuisson which had prevented him from traveling to the United States.42 Attempts to improve the image of the ineffable major, however, will not work either. The administration is forced to work with the rightists but, judging by what has happened in similar situations in other countries, it is unlikely that D’Aubuisson and ARENA will become useful instruments for a democratic transition in El Salvador.

Contrary to what some conservatives in the United States are trying to pretend, neither the major nor ARENA, the umbrella organization that the reactionary coalition has entrusted to him, can be described as “democratic capitalists.”43 They have come to power to give another try to the 1977-79 attempt by General Carlos Humberto Romero to stabilize the Salvadoran crisis through a restoration of reactionary despotism. This is their real intention, one which they stated publicly throughout the campaign. This is what they promised to their constituency. This is what people in El Salvador expect them to do.

In summary, the new alignment has made the restoration of reactionary despotism a distinct possibility. This does not mean that the chances for democracy are lost, since the outcome of a process of transition does not depend upon the actions of only one actor. In the short run, however, the outcome of the election has compromised the chances for a democratic resolution to the crisis.

Conclusion

In this century, El Salvador has experienced a series of crises that could have culminated in the inauguration of a democratic regime. The coup of 15 October 1979 initiated the most recent of these. Like several previous opportunities for a democratic transition, this one began with a military coup. A junta de gobierno was organized, which soon gave way to a more moderate one. The more extremist element of the Right maintained a relentless pressure against the enactment of any reforms and, once some were enacted, launched a violent campaign to stall the process and insert a new and decidedly conservative government that would reverse it. The military remained the key participant during the entire process, acting as the final arbiter in the most important decisions, retaining veto power, and staying above the law. The aperturistas were finally overwhelmed because they could not overcome the combined strength of the oligarchy and the military.

The process initiated in October 1979, however, differed from the previous ones in several respects. The reforms brought about by this transition undermined the basis of oligarchic domination. A real political party established direct links to the independent organizations of the popular sector and the working class. Peasants were given some modest yet real benefits. The reformist government stayed in office for over two years, thanks in large part to the support of the United States, and was able to hold a relatively free and fair election. Radical sectors of the petite bourgeoisie, the working and popular classes, and the peasantry organized a guerrilla army that battled the Armed Force to a standstill. Finally, the international linkages of the crisis became more pronounced, threatening to turn a civil war into a regional military conflict.

The Salvadoran military did not fill the power vacuum created by the oligarchy crisis of 1932, and during the last forty years it has prevented others from attempting their own solution. Throughout, though, a very broad and strong coalition has been necessary to conduct one of these crises to a democratic outcome.

The historical roots of the present crisis are Salvadoran. The United States’ involvement in it has been deepening, however, and its attempt to exclude the Left from the process in order to forestall a Communist takeover has contributed to the present protracted conflict. In addition, two American administrations have tried to stabilize the situation around a “center” comprising historical enemies that could and would not reconcile their differences.

Democracy and capitalism are not incompatible. As a matter of fact, most democratic regimes exist within capitalist states. Those states have implemented some kind of redistributive scheme, however, in order to buy social peace. Once this basic question is settled the political process deals with other questions in an incremental fashion, centering on the interaction between a government bound by the law and responsible and autonomous intermediary institutions of interest representation that restrain the exercise of public authority.

The plan to join democracy and capitalism in El Salvador is fraught with difficulties, not the least of which is the necessity for a thorough reform of the capitalist state. Given the characteristics of contemporary Salvadoran society, the oligarchic capitalism of El Salvador cannot be maintained without a great degree of coercion. The process that started in October 1979 began to address this fundamental problem and made some notable gains, but it had at the same time to bring the Salvadoran state under the rule of law.

On the economic question the managers of the Salvadoran transition received some cooperation from the Armed Force. In their attempt to enforce a lawful state, however, they had to confront the military and the oligarchy. The civil war complicated this. Basically, little has been accomplished thus far.

No adequate settlement of the Salvadoran crisis is possible without the resolution of these two issues: the socioeconomic question, centering on the issue of tenure and utilization of land, and the human rights question, centering on the issue of the supremacy of the law. For the moment, the situation is polarized between the vision of D’Aubuisson and the Salvadoran Right and that of José Napoleón Duarte and the Christian Democrats. The former, conscious of the historical precedent, are confident in their ability to survive these crises and in the logic that requires the subordination of democracy to economic expediency. At bottom, what they are defending is neither democratic nor truly capitalist. The Christian Democratic vision is that things can be different, but history and precedent are against it.

It has been argued here that a democratic outcome to the present crisis is not possible without the reincorporation of the democratic Left. The collapse of the first junta, the precarious situation of the Christian Democrats during 1980-82, and the outcome of the 1982 election support this argument.

The United States can still play an important role in the present crisis, a crisis which it did not create but which it has helped complicate. Unfortunately, the ideological make-up of the Reagan administration makes it unlikely that the administration will perceive an alliance between the Social and Christian Democrats as a viable and legitimate option. This is the greatest but not the only mistake that the U.S. could make. The attempt to solve the crisis through an outright military victory may be enhanced by the return of Salvadoran troops trained in the United States, and by the guerrillas’ slow recovery from their setback at the election. The temptation to link the Salvadoran crisis to other conflicts is still there.

The true colors of the disloyal Right are hard to hide. The U.S. Congress is not likely to accept that the disloyal Right is embarked on a reformist path and spearheading the defense of human rights in El Salvador. With the change in hemispheric relations brought about by the war between Britain and Argentina, the United States can no longer count on much outside help to do the dirty work in Central America. The fall of the Christian Democrats from power has led to a reevaluation of the situation by Venezuela, which had been a crucial partner in United States policy toward El Salvador. Finally, the level of violence may escalate again, not so much between the military and the guerrillas in the countryside, as between ARENA and PDC operatives in the cities. The whole fragile arrangement could unravel very quickly.

The yearning for peace expressed by Salvadorans on 28 March 1982 should not go for nothing; the lofty rhetoric that it generated has already been spent. Ordinary Salvadorans are waiting for an amelioration that cannot come the way they anticipated it. They cannot simply sit and wait until the Christian Democrats or some other aperturista faction finally wins a majority and manages to control the Armed Force. They have been waiting since 1972; the country has been waiting since 1932.

If precedent prevails the disloyal Right will have its way, and the election of 1982 will have marked the end of another attempt at a democratic transition—a cruel irony. If democracy is to emerge, the aperturistas need help. Those now in the government who want to restore reactionary despotism may, by their intemperate use of power, finally force a reluctant Reagan administration to link future aid to the maintenance of the reforms and, equally important, to the defense of human rights.

In this sense the United States could be the difference between history and hope, but it must be willing to run some risks. The greatest of these is not that El Salvador may become another Nicaragua or another Vietnam. Instead, the greatest risk is that we may have to accept that we are just the difference and not the essential ingredient.