Chapter 4

Deterioration of the Regime

From Repressive Reformism to Militarized Capitalism

Although Salvadoran scholars disagree over when a state of exception emerged in El Salvador and what exactly that entailed, nearly all agree that the Salvadoran system of controlled democracy underwent a profound transformation in the mid-1970s. This disagreement is fairly common in the literature of authoritarian regimes. For example, despite a relative consensus on the definitional characteristics of the “new” authoritarian regimes of South America, identified most frequently as “bureaucratic authoritarian” regimes or “national security” states, among a host of alternative labels, students of those regimes differ on which of their characteristics is most relevant.1

At least in the case of El Salvador, one cannot treat this purely as a question of semantics. An accurate diagnosis of the present Salvadoran crisis requires an informed understanding of the differences between the administrations of Arturo Molina and Carlos Humberto Romero, and between these and the governments organized after the coup of 15 October 1979.

Authoritarian regimes share a similar formula of political domination. In essence, this consists of a dictatorial government, maintaining a régime d’exception, that is, one above the law and beyond the constraints of intermediary institutions. Such a scheme depends on the ability of the government to exclude some sectors of the society from the political process and to prevent the opposition from becoming effective. Regimes differ in how they go about fulfilling these requirements, who the principal actors are, who their closest allies and main adversaries are, and how much violence they have to utilize in order to maintain power.

At first glance the term bureaucratic authoritarian appears applicable to El Salvador. The Salvadoran military institution has controlled the political process since 1948. The regime had to rely on an increasing level of violence between 1972 and 1979. Military officers occupied more positions in the government.2 The military closed ranks in an attempt to maintain control of an increasingly polarized political process. In addition, the Salvadoran regime, especially during the Romero administration, began to resemble the post-1968 government of Brazil, the regime of General Pinochet in Chile, and the Argentine military regime of the late 1970s more than it did the Salvadoran regime of the Rivera and Sánchez administrations.3

But let us not carry the analogy too far. The bureaucratic-authoritarian regimes of the Southern Cone came to power to replace socialist or populist governments that had become too threatening to some sectors of the society. Once in power these counterrevolutionary governments had to disarticulate many political organizations—primarily political parties, labor unions, and other voluntary associations—that were only beginning to emerge as actors to be reckoned with in El Salvador. With varying degrees of success, these governments tried to implement new economic models that would bring about more advanced forms of capitalism grounded on a more sophisticated industrial infrastructure. This was all but impossible in El Salvador, where the basic economic problems were how to dismantle the “magic square” of economic domination by the oligarchy and how to minimize the adverse effects of the commodity cycle.4

The term national security does not fare much better, because in El Salvador, as elsewhere, a characterization of the regime that makes use of only one aspect of the ideology of one of the dominant factions is not sufficiently comprehensive. Tomás Campos shows how the doctrine of national security gained currency with elements of the military during the 1970s.5 According to Campos, the doctrine emphasized anti-Communism, state autonomy, and the need to subordinate the exercise of civil liberties.6 More important, application of this doctrine, particularly during the Romero administration, unhinged the “normal” relations between state and society in El Salvador that had existed since 1948. It appears, however, that we must search for some other label to characterize the regime that emerged as a result of the application of the doctrine of national security. Otherwise, we might find ourselves examining a “crisis of the national security state,” which would be an inappropriate focus since it was not the national security state but the model of 1948 that was in crisis.7

The Salvadorans have come up with some terms of their own to try to define the kind of regime produced by the turmoil of the 1970s. For example, ítalo López Vallecillos talks about a caciquismo conservador (conservative bossism) to characterize the authoritarian, exclusionary, and autocratic regime implemented by Molina.8 The term is adequate, but it describes only a style of leadership and not really a type of political regime. Moreover, Molina’s attempt to play the reformist option one last time and the failure of this attempt made him a lame-duck president, enabling an even more conservative coalition of military and oligarchy actors to put Romero in power. Rafael Guidos Véjar refers to the last period of the Molina government as a “regency.”9During this regency, according to Guidos Véjar, the political organizations of the oligarchy became more important than the PCN.10 This view supports the argument that there was an important change in the composition of the government coalition from Molina to Romero.

Under the regimes of Colonel Arturo Molina, who began and ended his term under a state of siege, and his successor, Romero, an expert in counter-insurgency who served as Molina’s minister of defense, the military increased the distance between itself and civil society in general in an attempt to reassert its control and to protect its own institutional integrity from leftist subversion and rightist attempts to control the government. This effort was in vain, however. The armed forces could not replace the moderate political parties as the center of Salvadoran politics, they could not move the system in a new direction without redefining the nature of the state, and during the Romero administration, the oligarchy managed, once again, to penetrate the government thoroughly. After twenty years in power, the best solution that the Salvadoran military could come up with was a more repressive version of the system that had prevailed since 1948.

Under the banners of “definition,” “decision,” and “firmness,” Molina moved against the university, abrogated its autonomy, nominated a rightist rector, sent dissident faculty into exile, and sought to destroy the student organizations.11 The electoral campaigns of 1974, 1976, and 1977 were unabashedly fraudulent, with tamales—stuffed ballot boxes—transported in military vehicles and intimidation dispensed through the Organización Democrática Nacionalista (ORDEN). Molina continued the “reformist” line of the PCN: he nationalized the International Railroad of Central America (IRCA) concessions and turned over IRC operations to the Acajutla Port Authority, increased the minimum wage for agricultural workers, initiated a timid program of agrarian reform in 1975 by setting aside 150,000 acres of government-controlled land in San Miguel and Usulután, and created the Instituto Salvadoreño de Transformación Agraria (ISTA).

The creation of the ISTA brought about one of the most intense confrontations between the reformist faction of the military and enlightened elements of the industrial bourgeoisie, on the one hand, and the traditional oligarchy, operating through and assisted by the Asociación Nacional de la Empresa Privada (ANEP), the most important private sector organization, which included the cafetaleros (coffee growers), the Salvadoran Chamber of Commerce, the American Chamber of Commerce of El Salvador, and most of the agricultural associations, on the other. Therefore, this was not merely a conflict between civilians and the military but a contest between the two factions of the upper classes, each trying to take advantage of the fluid situation to move the military government in the direction of a model which was more attuned to their economic interests, as well as to their ideological preferences.

There were, to say the least, quite a few precedents for the political conflict that accompanied the raising of the land question in El Salvador. The most notorious in this century would, of course, be the matanza of 1932.12 Another would be the long period of 1932–73, during which the government considered the topic subversive. The PAR was declared illegal in 1967 on the grounds that its platform included a plank inadmissible in the established constitutional order—agrarian reform.13 A 1972 initiative by the PDC to discuss a project of agrarian reform did not even reach the floor of the legislature for debate. Other examples include the timid initiative of 1973–74. the creation of the ISTA in 1975, and the creation of the first district of agrarian transformation in 1976.14

The ISTA initiative received mixed reviews from leftist democrats in the opposition. Rubén Zamora, for example, called the initiative “an attempt to modernize the capitalist structure of Salvadoran agriculture [which could] create a relatively ample strata of small and medium proprietors.”15 By contrast, Luis de Sebastián saw the law as “a bourgeois reform . . . whose objectives included the suppression of latifundia and all the large estates . . . and the creation of a fairly egalitarian property structure . . . without confiscation [and in which] landowners must change their assets, that is, the source of their income.”16 Guillermo Ungo saw the ISTA project as one aspect of a process in which the military government sought to change the appearance of the existing system, modernizing it at the expense of the dominant faction, or agro-financial sector, of the oligarchy.17 This was another initiative from above, without grass-roots participation, as well as another attempt to steal the thunder from the opposition without converting the reform into a political program. However, Ungo believed that the new legislation marked the beginning of a new stage and a new normative orientation that went beyond previous ones, which had benefited only the oligarchy.18

More radical critics were less impressed. Oscar Menjívar and Santiago Ruiz saw the Agrarian Transformation as part of the Plan of National Transformation that the armed forces had vowed to implement “energetically,” so that the necessary changes would not disturb public order and “Communists” would not be able to take advantage of the situation. In short, to Menjívar and Ruiz, the transformation was a combination of structural change and military dictatorship to strengthen the capitalist model of development.19

Judging from the reaction of the “agrarian front,” it would appear that this most reactionary sector of the oligarchy, the government, and its opposition critics were talking about entirely different things altogether. In spite of the fact that the model adopted in the transformation was Taiwan’s—and not Cuba’s—that most of the land involved was government property, that the United States Agency for International Development (AID) would provide the money for compensation, and that the “agrarian reformers” were wearing a uniform that had always defended their privileges, the traditional oligarchy and much of the Salvadoran private sector went on the warpath. The ANEP played a key role in the campaign orchestrated by the private sector to resist these measures.

The ANEP, the organ through which the oligarchy and the bourgeoisie reconciled their differences and articulated their interests, published a declaration against the new agrarian legislation—Law-Decree 31 of 29 June 1976 creating the First Project of Agrarian Transformation—on 9 July 1976. The ANEP’S contradictory stance purported to welcome the transformation but decried “an orientation predicated on a negativistic state intervention in the economy.”20 Furthermore, the ANEP expressed dismay over the “surprise and haste” with which the government had passed the legislation: in twenty-four hours, ignoring public opinion, and trampling on the dignity of the Legislative Assembly.21 Finally, the ANEP argued that the lands affected by the decree were being worked intensively and efficiently, at a high rate of productivity and labor utilization.22

On 10 July the government responded with a communiqué of its own, stressing the fact that the enabling legislation—Law-Decree 302 of 30 June 1975 creating the Salvadoran Institute of Agrarian Transformation (ISTA)—had been in place for a whole year. In addition, the government expressed its own surprise that the ANEP had overlooked “clear and concrete announcements made by the President,” beginning with his inauguration.23

The ANEP’S rejoinder of 13 July underlined the dire consequences that the measure would bring about—production and export shortfalls that would affect the standard of living of the population—and the impossibility of making everyone residing in the affected area a landowner, given its high population density. The bottom line, it said, was that the Salvadoran economy could not “withstand experiments in agrarian policy” and that the ANEP was against this project because it undermined the very bases of the economy.24

A 14 July rebuttal by the government attacked the second declaration of the ANEP by singling out its instigators as a small, intransigent group and citing the endorsement extended to the project by a group of experts from the Simeón Cañas University and the government’s awareness “of the situation in which most Salvadorans live . . . as well as of its causes.” Finally, the rebuttal rejected the ANEP’S contention of haste and improvisation.25 Surprisingly, the government’s document alluded to the problems created by those who neglected their fiscal obligations and warned that, if “unable to reconcile the interests of the majority without means with the interests of a minority in possession of everything, [the government] reiterated its historical compromise with the former.”26

The ANEP’S final note to the government protested its “totalitarian stance” and “absolute intransigence,” and reminded the government of its “obligation to listen.” The ANEP stated that the organization would continue to air its views without fear.27 On 16 July a very detailed and bitter response by the government included seven points: (1) only the government was responsible for the political direction of the country, (2) the ANEP’S leadership was intransigent and selfish, hiding behind a facade of social concern, (3) the project strengthened private property, (4) the government would listen, “but the act of listening should not be confused with the action of obeying,” (5) the ANEP’S preoccupation with verbal violence should turn into a preoccupation with the explosive situation that its closed and unjust opposition could create, (6) many of the ANEP’S leaders had occupied government positions and had failed to take any action, and (7) the government would not default on its 1 July 1972 commitment to serve the majority.28

It is difficult to think that President Arturo Molina acted alone on this matter, without at least consulting the more senior military officers. It appears that the military had been discussing the issue during Molina’s term, as witnessed by a national seminar on agrarian reform prepared for officers of the armed forces and conducted in August 1973, as well as by the substance of Molina’s declarations in a series of speeches delivered during his term of office.29 Moreover, shortly after the announcement of the first ISTA project, the government organized what was, according to Rubén Zamora, one of its largest public gatherings of the last fifteen years, bringing to San Salvador between 70,000 and 100,000 peasants of ORDEN.30 This took place on the occasion of the fourth anniversary of Molina’s coming to power and on the eve of the angry exchange between the government and the ANEP in July. Finally, Molina launched a two-pronged campaign to explain the Agrarian Transformation to the armed forces staff, line officers in the various garrisons, and government bureaucrats during July and to stir up support through the media during August.31

Although the majority of the organizations appearing as signatories of the first proclamation of the ANEP were associated with the “agrarian front,” a number of organizations from other sectors were also included in the manifestos.32 Both the oligarchy and the bourgeoisie seemed united in their objections to the First Project. In its position as junior partner the latter may have gone along reluctantly, in the hope of serving as a mediating force between a government embarking on a project that could help the industrialists in the long run and the traditional oligarchy, which saw little if any gain from it. However, as Zamora argues, the Salvadoran bourgeoisie has been consistent in its opposition to any restriction or limitation on property.33

The timing of the execution of the transformation is not hard to understand. The government was one year away from another general election and, as usual, preoccupied with the electoral prospect. More to the point, there was a real likelihood that a repeat of the fraud of 1972 would be necessary, with the inevitable loss of prestige, public unrest, and general discredit of the military. From a longer perspective, and not unrelated to this, the government had to offer some tangible benefits to the PCN constituency, namely, the small and medium-size cultivators integrated in ORDEN, the agricultural laborers, who might still find the UCS attractive, and other sectors of the peasantry which were beginning to move away from the PCN. The political activation of these groups outside the government-controlled channels was a subject of concern for the agricultural entrepreneurs, but for the government such an activation posed a problem of public order and required “energetic response.” Apparently, Molina opted for reform, trying to take advantage of available AID support for his initiative.

But like his predecessors, Molina lacked a true political party to support his policies in time of need, especially if opposed by the oligarchy. At the outset, he had institutional support from the military, the governmental bureaucracy, and the “official peasantry.” He may have hoped to bring some of the uncommitted aboard, but the PDC was still smarting from the fraud of 1972, the fledgling popular organizations did not trust the government, and the institutions of the progressive element of the bourgeoisie were silent or nominally on the side of the ANEP.34 To be sure, the ANEP continued to air its objections “without fear.”

Beginning on 19 July the ANEP and its affiliates saturated the media with a barrage of propaganda. The tone and tenor of this campaign was one of hysterical anti-Communism; in addition, the exclusion of the peak private sector organization from a policy decision was made no less an issue than the substance of the transformation itself.35 The ANEP was joined in its campaign by a chorus of phantom organizations—the Civic Committee, Western Agriculturalists, Committee for the Defense of Human Rights, Eastern Agriculturalists, Uncommitted Catholics Group, Cereal Growers of El Salvador, Committee for the Defense of the Social Function of Private Property—which came out of nowhere to attack the government. Most prominent among these was the Frente Agrario de la Región Oriental (FARO), which adopted a militant posture, instructing landowners on how to resist the implementation of the transformation through dilatory tactics. Gradually, the target of these attacks became the “planning group at CONAPLAN” (the National Planning Council), the Jesuits at the university, and unpatriotic Salvadorans.36

It is interesting that throughout this crisis none of the figures who were viewed as representatives of the private sector holding portfolios in the government resigned his position. This may have been an indication of a breakdown of consensus within the NEAP or of individual support for the transformation or it may simply have been a means of maintaining a presence for the private sector within official circles to channel demands and mediate the dispute. The more recalcitrant element of the “agrarian front,” however, felt compelled to form its own organization, the FARO, and take more resolute action. Given the heterogeneity of the economic interests and political viewpoints expressed within the ANEP, the traditional oligarchy, feeling more threatened by the transformation than were the industrialists, may have embarked on a new course of action by itself.

The fact remains that by October 1976 the government had lost the initiative. The transformation was being shelved, and in spite of his unwavering commitment to the majority of Salvadorans, Molina was retreating. The retreat was greeted by those who had supported the transformation with ill-disguised contempt for those who were really “at the service of Salvadoran capital.”37

The question whether this was a personal defeat for Molina, who had to govern as a regent during the rest of his term, unable even to extend official protection to those who had supported him, a defeat for the reformist faction of the armed forces, or a defeat for the military institution itself remains open to debate.38 The safest hypothesis would make Molina the goat, but, after all, his presence in power was the result of a blatant electoral fraud, so his commitment to reformism was always in question. On the other hand, the reformist faction of the military, whatever its actual size and political influence at the time, had been in no position to dominate its own institution; nor had it seemed to have “captured” the Molina government. At best, that faction could have advocated or joined in the initiative, which was, after all, Molina’s, who could be blamed for its failure.

If López Vallecillos is right, however, the loser in the crisis of 1976 was the military. López maintains—and he is not alone in this—that in 1931 the armed forces were given the task of managing the state institutions, a role that was expanded under the social pact of the Constitution of 1950 to include some participation in the development of the country.39 The defeat of 1976 was one more in a series of episodes in which the military tried to include the popular sectors in redistributive schemes, making some advances in times of prosperity but beating a pell-mell retreat at the end of a twelve-year cycle.40 In this line of reasoning, therefore, the military—and not Molina alone—exceeded its assigned role and had to be put in its place by the traditional oligarchy. The ANEP played a role in this campaign, but the traditional oligarchy assumed the leadership of the movement, creating the FARO and distancing itself somewhat from the more moderate and heterogenous ANEP.

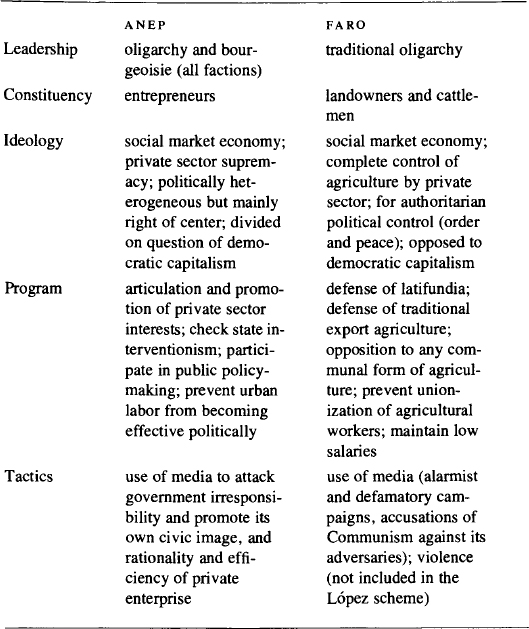

The very useful comparison between the ANEP and the FARO offered by López Vallecillos is reproduced below, albeit with some minor alterations (see Figure 4-1). In practically every category of comparison the FARO comes out as more radical and specific. It was not only more homogeneous in constituency and leadership but also more specific in its goals and programs and more radical in its tactics. Concerning the latter, it is apparent that the FARO was more prepared to use violence than were many of the organizations and entrepreneurs represented in the ANEP. Although the evidence is sketchy, it appears that the FARO was one more attempt by traditional conservatives to regain the degree of political power that their cause had once enjoyed, and that had been deteriorating since 1948. For example, a comparison between the FARO and Chele Medrano’s FUDI (see Figure 3-2 above) reveals an impressive number of similarities between the ideology, programs, tactics, and clientele of the two organizations. But the FUDI, like the PCN, was only an electoral mechanism, and in a moment of crisis, such as that of the ISTA, the oligarchy wanted a more reliable and decisive instrument of pressure and mobilization. Apparently, it got it in what Guidos Véjar—referring to the FARO— called “a sort of corporation and political party of large landowners which successfully led the campaign . . . against the Agrarian Transformation.”41

FIGURE 4-1

Peak Private Sector Organizations in Late 1976

Adapted from López Vallecillos, “Fuerzas Sociales,” pp. 576–77.

But let us not exaggerate the “subordinate role” of the Salvadoran armed forces. The oligarchy maintained its class superiority by “inviting” a select few to join its ranks after they had retired from the military, and few in the military were welcomed with open arms into the more exclusive clubs of San Salvador. This does not mean, however, that the military was the errand boy for the oligarchy or that a majority of the officers saw themselves in that capacity. For example, as astute an observer as Zamora could not detect a single instance of criticism against the military institution among the proclamations of the ANEP against the transformation. By contrast, a reading of the government manifestos shows frequent references to armed forces support for the transformation and direct attacks against “a few selfish individuals.”42

In short, the behavior of the private sector vis-à-vis the government seemed an attempt to undermine support for Molina and his initiative, but not to question the legitimacy of the military’s presence in power. The complaint was based on a perceived transgression of the pact of 1948, in which the military institution gave itself the right to rule and pledged not to interfere with the basic mechanisms of capitalist accumulation. Therefore, as had happened before, the oligarchy, aroused by an attempt to modify the traditional division of jurisdictions, was able to put the military on the defensive by implying that the government was subversive.

There are several versions of the nature of the crisis in El Salvador. Most authors allude to a gradual divergence between the interests of the traditional oligarchy and of the modern sectors of the bourgeoisie. There seems to be agreement that the latter could not dominate the former but that, somehow, they managed to control the military government. It is one thing to prevent government interference, that is, to resist government initiatives, however, and quite another to force the government to do something. Apparently, the Salvadoran private sector had sufficient influence to do the former but not enough power to do the latter. This probably suited the bourgeoisie fine, since the process of change would ultimately give it the opportunity to become the dominant group. But in order to maintain itself, the traditional oligarchy had to force the government to take action to defuse the process of change that was undermining its economic and political influence.

It would be simplistic to aver that the Salvadoran oligarchy precipitated a civil war. One important lesson that contemporary Salvadoran politics teaches is that in such a complex process no single actor, no matter how powerful, can dictate outcomes. It is apparent, however, that the traditional oligarchy of El Salvador tried to move the government in the direction of a system which included aspects of the traditional authoritarian model, with some elements borrowed from the national security or bureaucratic authoritarian regimes of the Southern cone. The experience of the ISTA crisis may have signaled to the traditional oligarchy that if it was going to save itself, it had to take much more drastic action. Therefore, it tried to break a “catastrophic balance,” not between itself and the industrialists, which it could still dominate, but between itself and the armed forces in an attempt to restore itself to power. Using their extensive contacts and summoning all the influence they could muster, the members of the traditional oligarchy tried to make the conservative faction of the military the dominant group within the institution, to initiate a process of exclusion and extermination of their class enemies, and to utilize reactionary despotism to bring about their resolution of the crisis that El Salvador had suffered since 1931. These attempts contributed to the country’s drift toward civil war.

The fact that the traditional oligarchy failed in its short-lived attempt to “restore” reactionary despotism does not invalidate this interpretation of the nature of the organic crisis of hegemony in El Salvador. Instead, the oligarchy’s failure to consolidate this restoration is one more indication of the complexity of the crisis and of the difficulty that any one coalition of actors faces in trying to produce a stable and viable system of domination based on an exclusionist authoritarian model.

Finally, it is clear that the ISTA crisis contributed to the polarization that was eroding the prospects for a reformist solution. The failure of the Agrarian Transformation of 1975-76 only aggravated the lawlessness of the Salvadoran state. The new administration of General Carlos Humberto Romero took office already stripped of any reformist pretenses and ready to do battle with the opposition.

From Molina to Romero

Molina sowed so much discontent that during his term the popular organizations grew dramatically and the climate for guerrilla operations improved markedly. New patterns of violence emerged, elements within the Catholic church increased their demands for change, and the regime became the target of constant criticism from human rights organizations.

Romero simply made matters worse. He dropped all pretensions of reformism and made an open alliance with the extreme Right in order to face the common enemy, which grew stronger and bolder. Under Romero, a hardline anti-Communist, the government and the right-wing paramilitary organizations drew closer together. The “official” paramilitary organization, ORDEN, was used constantly to counteract the efforts of the popular organizations, and especially of the peasant organizations, ORDEN had been created by Colonel Rivera in 1966 for precisely those ends, but never before had its use been so peremptory. The coordinator of ORDEN responded to the executive directly and was not, in a strict sense, in the chain of command of the military. The cadre and the rank of the organization, however, came from army reservists and retired security officers. The organization grew to become a militia force of between fifty thousand and one hundred thousand armed peasants used to maintain “order” in the countryside.

In the mid-1970s the activism of priests and religious in organizing peasants created a dilemma for the Romero government. To counter this, new “unofficial” groups of right-wing terrorists appeared. In 1975 the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Anticomunista de Guerras de Eliminación (FALANGE) emerged, promising to exterminate all “Communists” and their allies and denouncing bishops, priests, deputies, and even military officers. The hierarchy, clergy, and lay people of the Salvadoran Catholic church played a very important role in undermining the Romero government.43 Inspired by revisions of Catholic social doctrine—primarily the Declaration of Medellin of the Latin American Conference of Bishops (CELAM) and the assumptions of “liberation theology”—Salvadoran Catholics became formidable adversaries of the regime through their campaigns of “consciencitization” and political organization. It was only a matter of time before the military decided to take action.

In March 1977, Fr. Rutilio Grande, S.J., an organizer of peasants in Agui-lares, was killed.44 In May, Mauricio Borgonovo, who had served as Molina’s foreign minister and was a figure in the oligarchy and a business partner of former president Arturo Molina and of Anastasio Somoza, was assassinated. He had been kidnapped by the guerrillas. In revenge the Unión Guerrera Blanca (UGB) took the life of Fr. Alfonso Navarro, a diocesan priest. TheUGB had emerged in April, during the crisis over the Borgonovo kidnapping; in June it issued a death threat against all Jesuits residing in El Salvador.

The escalating conflict between the church and the government had very profound consequences. First, the deepening rift was one of the proximate causes in the deterioration of the Romero government. The newly inaugurated archbishop of San Salvador, Oscar Arnulfo Romero, repeatedly denounced government repression and terrorism and refused to adopt a more conciliatory attitude unless the government stopped its persecution of the church and its repression against the Salvadoran people. When one conservative bishop decried the “radical” attitude of the Salvadoran church, he was quickly rebuked by the Vatican for ignoring “the genuine, brave and heroic ministry that many priests and catechists were developing in the country.” In sum, church criticism eroded the little legitimacy that the government of Romero had left.

A second important consequence of the repression against Catholic activists was the public outcry abroad. The UGB’S death threat against the Jesuits led the Carter administration to express grave concern and forced Romero to extend government protection to them and to allow a number of inquiries into the human rights record of his administration to be conducted by such international groups as the Inter-American Committee on Human Rights, the International Commission of Jurists, and a British parliamentary delegation. The reports produced by these inquiries were uniformly critical of Romero, whose government came to be regarded as “one of the world’s worst violators of human rights.”45

In March 1977 relations between El Salvador and the United States reached a low point when the government of Molina rejected U.S. attempts to link military assistance to observance of human rights, refusing the aid altogether. This made El Salvador’s the fifth Latin American government to follow that course of action, joining a group that included the most repressive regimes of the Southern Cone. The findings of the human rights inquiries suggested that the Salvadoran government had more in common with those governments than a mere refusal to subordinate arms deliveries to self-restraint. In sum, the inquiries found that the rule of law no longer governed the “normal” treatment of opposition by the Salvadoran government.

Foreign pressures did not deter Romero from enacting a tough public order statute in November 1977, which received scathing criticism in the report prepared by Donald Fox, a New York attorney, for the International Commission of Jurists.46 Findings like these forced the Carter administration to take its pledge to human rights seriously in the Salvadoran case, contributing to the increasing international isolation of the Romero government and sapping it of what little legitimacy it still enjoyed, having come to power as a result of another electoral fraud and having quickly accumulated such a dismal record of systematic violations of human rights.

According to Guidos Véjar, the Law for the Defense and Guarantee of Public Order, passed on 24 November 1977 by the Romero administration, responded to a series of demands by the private sector to deal more firmly with the opposition.47 The ANEP and the FARO appealed to the military, not the government, to deal with the growing pressure of the mobilization of the popular sectors, which included labor demands as well as a demand for the cessation of the increasing repression directed against them.

The law was relatively ineffectual in dealing with labor unrest, however, since between November 1977 and February 1979, the period during which the statute was in effect, there were more than forty illegal labor strikes in El Salvador.48 In addition, popular organizations, primarily the Bloque Popular Revolucionario (BPR) and the Frente de Acción Popular Unificada (FAPU), tried to create a “labor front” which would press labor demands through a combination of legal and illegal methods.49 By July 1979, although the three dominant federations remained intact—the Confederación Unitaria de Trabajadores Salvadoreños (CUTS), formerly under the control of the Communist Party; the Confederación General de Sindicatos (CGS), with the closest ties to the regime; and the Federation of Unions of Construction and Transportation (FESINCONSTRANS), which had been the most successful in gaining concessions since 1968 and maintained some linkages with other government unions, such as the UCS—their links with the political parties seemed to be eroding, and as a result, the government’s ability to control labor unrest was diminishing.50

The Public Order Law was practically a license to kill. Of course government violence against the opposition in El Salvador was not invented by the Romero administration, but there was a stunning increase in acts of violence against an opposition which the Public Order Law had put in the category of subversive. Under Romero, government violence reached epidemic proportions. Considering only government-initiated violence, political assassinations increased tenfold, prosecutions of “subversives” increased threefold, and the number of disappeared doubled (see Table 4-1). In addition, four Catholic priests were killed by security forces or their proxies.

The guerrillas, for their part, also increased their use of violence. The number of their actions doubled, their killings of security and paramilitary personnel increased twofold and threefold, respectively, and the number of political kidnappings doubled. The Fuerzas Populares de Liberación Farabundo Martí (FPL-FM) engaged in a series of political assassinations through 1978, including Borgonovo’s (10 May), former Consejo Central de Elecciones (CCE) secretary René Guzmán (1 July), former police chief in charge of the matanza and provisional president Osmin Aguirre (12 July), the rightist rector of the University of El Salvador Carlos Alfaro Castillo (16 September), and former president of the legislature Rubén Alonso Rodríguez. The Fuerzas Armadas de Resistencia Nacional (FARN) kidnapped two foreign businessmen in 1978, Fujio Matsumoto and Kjell Bjoerk; Matsumoto was killed when the government refused to negotiate, while Bjoerk was freed in August after his company paid for the publication of a guerrilla manifesto in Central American and foreign newspapers. The Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP) engaged in a series of bombings of government offices, industrial plants, the Nicaraguan embassy, and other installations of some symbolic value to the guerrillas. It is important to emphasize that the Salvadoran guerrillas were practically nonexistent until the mid-1970s, when a climate more conducive to their activities was created by the repressive policies of the government.

This political mobilization was not a result of a Communist conspiracy; nor was it a direct result of the difficult social circumstances of the popular classes. It is true that 90 percent of a work force of 1.75 million Salvadorans were paid, when employed, salaries below minimum wage and that they faced very harsh economic conditions. But persons do not become politically activated or change their styles of political participation unless they realize the futility of individual action. To these Salvadorans, their only strength was in their numbers. Therefore, the reason for the success of the Federación Cristiana de Campesinos Salvadoreños (FECCAS) and the Unión de Trabajadores Campestres (UTC) among some sectors of the peasantry and the ability of the popular organizations to mobilize thousands of persons must be sought in the new organizational strategies through which they proposed to redress grievances.

Unlike the professionals and members of the middle class who tried to expand the franchise, create effective suffrage, and begin a process of democratic transition in the 1960s and early 1970s, the members of the popular organizations could not go back to their professions and simply wait for a better opportunity. They bore the brunt of the most profound contradictions of Salvadoran society, and they found themselves on the receiving end of repressive political measures designed to maintain an order which excluded them from the market and, by implication, excluded them from citizenship. It was only natural that they would react in similar fashion and begin to use political means to change their economic plight.

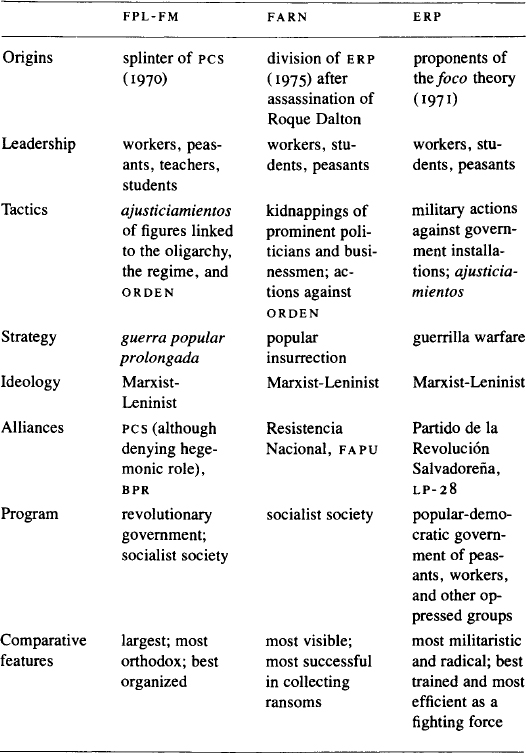

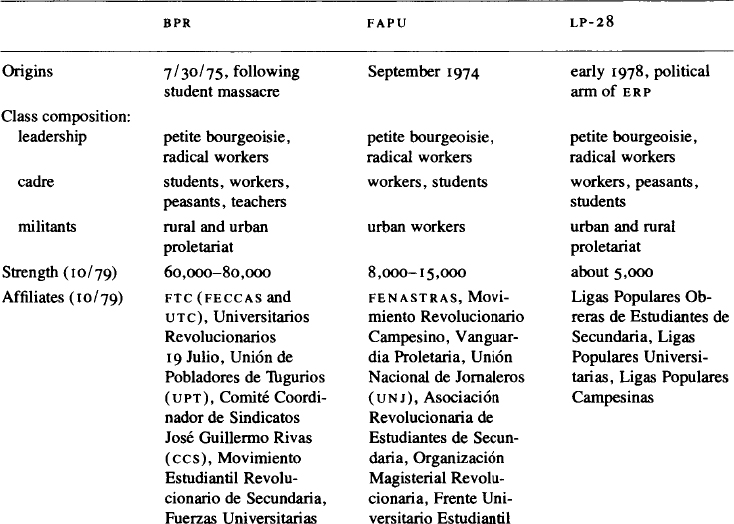

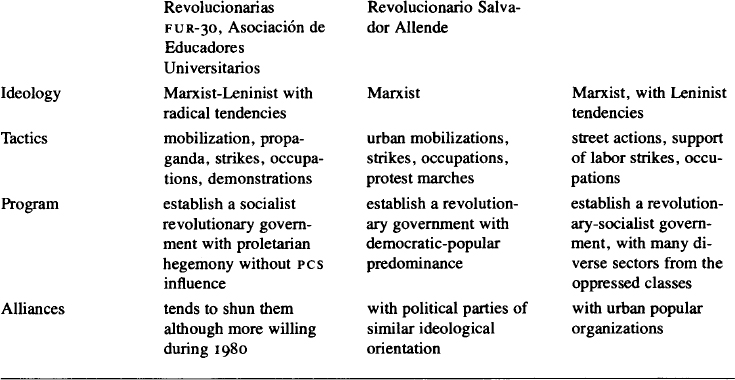

It is important to point out the differences between the guerrillas and the mass organizations. “Mass organizations” are the broad fronts of popular organizations that emerged in El Salvador in the mid and late 1970s: the Bloque or BPR, FAPU, the Ligas Populares 28 de Febrero (LP-28), and the smaller and much more recently created Movimiento de Liberación Popular (MLP; 1979). These organizations were subversive under the formula of domination prevailing in El Salvador, which would not grant them legal recognition. Unfortunately, attempts by the Romero government, by the private sector, and by the local media to identify them as “terrorist” were successful, since the international media adopted this label uncritically. But their ideological affinity and organizational links to the guerrillas should not overshadow the differences between the two types of organizations. These could be illustrated by comparing the information presented in Figures 4-2 and 4-3.

FIGURE 4-2

Guerrilla Groups in El Salvador

Source: López Vallecillos, “Fuerzas Sociales,” pp. 574–75; our own evaluation from sources identified in the text and personal interviews with Salvadoran exiles.

It appears that only the LP-28 could be considered a satellite of a guerrilla organization, the ERP, which seems to have created the former to have its own political vehicle. As the most radical and militaristic guerrilla organization, the ERP may have felt the need to create the Ligas in order to combat leftist criticism of its militarism and to serve its attempts to control the opposition. Since the FAPU was created before the FARN, and since it includes what is perhaps the most powerful labor federation in El Salvador—the Federación Nacional Sindical de Trabajadores Salvadoreños (FENASTRAS)—as well as a wide variety of other popular and labor organizations, it is unlikely that the guerrilla organization can dominate the FAPU completely. Finally, the connection between the BPR and the pes is real, but there are a number of organizations included in the Bloque, such as the FECCAS and the UTC which are not Marxist in orientation and which respond to radical Christian Democratic leadership.

According to Charles Anderson, the “price of admission” into the Central American political arena has two installments: first, a demonstration of a “power capability” and, second, a willingness to abide by the existing rules.51 In the 1970s these conditions no longer held in El Salvador, since when the popular organizations “showed off” their power capabilities—mainly the strength of their numbers—through acts of civil disobedience, which were the only ones available at that time, the government unleashed ORDEN, the UGB, and the FALANGE on them. In short, the popular organizations emerged as a result of the obsolescence and unfairness of the rules of the Salvadoran formula of domination.

The specter of how they would behave if they were legalized remained, but conservative fears about the possibility of a government primarily oriented to them were not only ideological but also practical. Could such a government govern effectively? Middle-class apprehensions centered on considerations about the kind of violence that the oligarchy would utilize to prevent the creation of such a government.52 During 1977–79 civil disobedience, demonstrations, and takeovers of churches, government buildings, and foreign embassies were the primary violent tactics utilized by the popular organizations, but these were met by a much more violent response from the Romero government.53 The result was a “praetorian” climate, that is, a situation in which a regime with a low level of institutionalization must deal with increased political mobilization. Two outcomes were possible: more repression to crush the opposition or a change of government.

FIGURE 4-3

Mass Organization in El Salvador

Source: Campos, “Seguridad Nacional,” pp. 924–25; López Vallecillos, “Fuerzas Sociales,” pp. 572–73, and “Rasgos Sociales,” pp. 870–71, 873; Virón Vaky, Testimony before U.S. Congress, House, Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Inter-American Affairs, Foreign Assistance Regulation for Fiscal Years 1980–1981, part 5, 96th Cong., 1st sess., 1979.

The threat initially posed by the popular organizations fell considerably short of a Marxist takeover—the “another Nicaragua,” which began to cause so much consternation in late 1979. The basic problem of the people that these organizations served was a living wage, and their best weapon was to organize. Once they were organized, the exclusionist formula had to be changed or they had to be crushed, à la 1932. The reasons were simple. The Salvadoran oligarchy did not want to readjust its living standards or to share economic power. The Salvadoran military saw any attempt to organize outside the control of the government as inherently dangerous and popular class organizations as simply subversive. Under the model with which it was working, the military could not allow the popular classes to become a political actor. The system that had prevailed from 1948 to 1972 precluded the popular classes’ enjoying full-fledged citizenship, and the changes, the endurecimiento, in that system following the debacle of 1972 had been made to make sure that this remained the case. In essence, political exclusionism and exceptional, that is, coercive, capitalism were the two basic ingredients of the Salvadoran model of the late 1970s, which is best described as reactionary despotism. This model was intended to prevent democratic reformism, not to fight Communism. The electoral fraud of 1977 and the Public Order Law of November of that year made this more explicit.54

But Molina’s defeat of 1976 in the ISTA affair and Romero’s closer collaboration with the traditional oligarchy should not obscure another, and perhaps more subtle, change that took place during the late 1970s. This must be sought in the greater distance that the Salvadoran military tried to interpose between itself and civil society in general. The close collaboration between the extreme Right, acting through its paramilitary organizations and the FARO, and the more reactionary elements of the military and the PCN is a matter of record and needs little further elaboration.

This alliance did not extend to all issues in the public agenda, however. For example, a rift developed between the Asociación Salvadoreña de Beneficiadores y Exportadores de Café (ABECAFE), a bastion of the oligarchy, and the Compañía Salvadoreña de Café (COSCAFE), a state enterprise, over the matter of export sales. In 1978 the COSCAFE found it necessary to restrict exports in an attempt to counteract a fall in coffee prices. This provoked the wrath of the ABECAFE, which was controlled by the thirty-six family groups who monopolized exports. Despite this formidable opposition, the COSCAFE maintained the ban until August 1979, when prices were more favorable and export sales were resumed.

Given the bloody conflict going on at the time—and what was yet to come—historians and students of El Salvador may overlook this contradiction between the interests of the state and those of the oligarchy. It is clear, however, that the reactionary coalition between the traditional oligarchy and the conservative military broke down in matters as significant as trade policy.55 This does not deny in any way the existence of a defensive alliance to maintain order and prevent the mobilization of the peasantry and the popular classes. But it emphasizes the ideological nature of that reactionary alliance, which, given the changes in Salvadoran society, was very unstable and could not be maintained for very long, regardless of the amount of violence used to consolidate it.

This is an exceedingly important point if one is to understand the nature of the relations between the military institution and the oligarchy following the coup of 15 October 1979. This apparent reappraisal by the military of the interests of the Salvadoran state—as different from those of the traditional oligarchy—was not carried to its full implications after the coup, but it provided a rationale for a different relationship between the military, as an institution serving the interests of the state, and the oligarchy, which had monopolized the interpretation of those interests up to that moment.

It goes without saying that Romero’s strong-arm methods did not neutralize the praetorian situation; nor did he provide the basis for a comprehensive settlement of the large questions facing Salvadoran society. Romero had to repeal the Public Order Law in February 1979 under intense pressure from the Carter administration, the Catholic church, international organizations, and even some elements of the Salvadoran private sector and military. In May the government organized a National Forum in a desperate attempt to ease tensions and tried to point to the next scheduled elections as a possible solution to the crisis. But the nation was still mindful of the most recent electoral fraud, which had robbed the candidates of the opposition coalition—Ernesto Clara-mount, a retired army colonel, and Dr. José Antonio Morales Ehrlich, his Christian Democratic running mate—of a certain electoral victory in 1977. Perhaps more important, the fall of Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua and the emergence of a popular government with socialist inclinations in that country prompted the Carter administration to seek an alternative to Romero in order to prevent a repetition of that kind of outcome in El Salvador.

The bloodless coup of October 1979 was an attempt to inaugurate a government based on a new political model in El Salvador. However, this attempt excluded the popular organizations, and this, viewed in the context of the last thirty years of Salvadoran politics, constituted a major strategic mistake, since it compromised the chances that the process of transition initiated then could result in a genuinely democratic outcome. The new coalition could not be consolidated, nor could the Salvadoran political system regain its equilibrium, unless the economic power and the political influence of the oligarchy were neutralized and the role of the military institution redefined. This required the fulfillment of two broad objectives: a restoration of the rule of law and a redefinition of Salvadoran political economy. Given historical precedent, these two objectives would meet the obstinate opposition and obstructionism of the oligarchy and the conservative elements in the armed forces. In light of the experiences of previous juntas and transitional governments in El Salvador, any government that committed itself to those two goals had to be built on as wide a base of popular support as possible. It had to be established on a new alliance that would bring together the petite bourgeoisie and organized labor, already represented by the PDC and the MNR, and the popular classes and the peasantry, whose only outlet at the time was the popular organizations but who were, in reality, the natural constituency of the MNR or other Social Democratic parties. In short, a formidable force—represented by this kind of coalition—was required to displace the immovable obstacle of oligarchic power and military control.

The execution of this blueprint implied undeniable risks and not a small amount of intense conflict. The basic dilemma confronting the conspirators of October and those whom they invited to participate in their government was whether to run that risk—and to be prepared to pay the costs that it entailed— or to take short cuts and play a safer game in which a pluralist solution would somehow seek to accommodate the oligarchy and the army, leaving the popular organizations out of the picture. It is a basic premise underlying the analysis to follow that neither the restoration of the rule of law nor a program of socioeconomic reform could take place in a pluralist context if this implied the maintenance of an effective veto for the oligarchy and the military. Nor could a democratic outcome be forthcoming without the implementation of a program in which all actors willing to abide by the law would be invited to participate, irrespective of ideology or social status.