Chapter 7

The Reagan Administration and the Salvadoran Civil War

Reagan’s Salvadoran Policy

The Carter and Reagan administrations shared one basic objective in their policies toward Central America in general and toward El Salvador in particular, namely, to prevent a victory by the Left. This was, after all, the principal motive behind United States support for—some would say active participation in—the coup that overthrew the Romero government in October 1979. During his brief tenure as United States ambassador to El Salvador, Robert White repeated this dogma on several occasions and promoted a line which tended to minimize popular support for the guerrillas and the political significance of the FDR. Containment of the Left in Central America was a goal shared by relatively broad sectors of opinion within the foreign policy apparatus, irrespective of their support for currently existing policies. For example, a position paper drafted by junior analysts and circulated through dissent channels during the final stages of the Carter administration criticized United States policy toward Central America, but did not question the assumption that the Left had to be contained.1

The difference between Carter and Reagan, in practical terms, would have to be sought in the particular blend of reformist measures and military muscle that each man felt was necessary to resolve the crisis. This difference became apparent in the approach of the Reagan administration to three issues: first, the question of human rights abuses and indiscriminate killings by the Salvadoran armed forces; second, the question of the relationship between the Duarte government and the Salvadoran private sector; and third, the question of a political settlement to the crisis, which was closely related to the way the administration perceived the whole situation and the more effective potential remedies.

The Issue of Human Rights

The area where critics of the Reagan administration’s policies toward El Salvador had most cause for concern was human rights. The administration’s views on a number of issues related to human rights seemed to confirm worst-case expectations. One such issue was the role of religious activists in the conflict. The administration’s reaction to the assassination of the four missionary women was a litmus test for this issue.

Emotions ran very deep. On 29 April 1980, Ambassador Robert White had sent a letter to Fr. Simon Smith, executive director of the Jesuit liaison office on missions in Latin America, expressing his concern that “a great number of people in El Salvador, specifically including the Jesuits, are so justifiably angry at the absence of human rights over the last half century that they have a psychological need for a bloody revolution.”2 Ambassador White’s letter concerned the events surrounding the shooting incident at the funeral procession for Archbishop Romero in San Salvador. Official preoccupation with the church’s unwitting contribution to violence, therefore, could also be found in the language of American officials before Reagan came into office. Yet it was Ambassador White’s rage at the murders of the four American missionary women in El Salvador that had, after all, led to his early confrontation with and departure from the Reagan administration.

By contrast, Secretary Haig dismayed and angered critics with his careless, tactless, and offensive comments on the circumstances of the murders. Haig told the House Foreign Affairs Committee that perhaps the vehicle in which the nuns were riding tried to run a roadblock, or may have accidentally been perceived to do so, and there may have been “an exchange of gunfire” in the process. The secretary, a master of the nonresponse and the obscure reply, may have dug himself in a deeper hole when he was asked by Senator Claiborne Pell, during a hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, to explain what he meant by “exchange of gunfire.” Haig said that he did not mean that the nuns were firing at people. Then he chuckled and added, “I haven’t met any pistol-packing nuns in my day, Senator.”3 One outraged editorialist related the exchange a few days later and asked the secretary, “Have you no decency, Sir?”4

The sarcasm of the secretary’s remarks was taken by many as a true measure of the administration’s feelings on the issue, overlooking more sober appraisals by other key figures, like that of Ambassador Kirkpatrick. Responding to a letter addressed to her by senators Charles E. Percy and Claiborne Pell, the chairman and ranking minority member, respectively, of the Foreign Relations Committee, Dr. Kirkpatrick replied that statements that she had made during an interview on “Meet the Press” reflected her attempt, as a political analyst, “to describe dispassionately a tragic violent scene,” and were not at all intended as a smear on the reputation of the victims. Kirkpatrick added that although the commitment of many priests and religious to political and economic justice in Central America led their adversaries to perceive them as political activists on behalf of the Frente (FDR), she did not believe “that anyone’s commitment to any cause or anyone’s help to any individual in any sense justifies their murder.”5

To bolster the credibility of its approach to the human rights question and to respond to criticism of the administration’s handling of the murder of the four American missionaries, the Reagan administration made public protestations of its concern with violence in El Salvador. On 9 April, Department of State spokesman William J. Dyess protested the killing of twenty-four slum-dwellers in San Salvador by the security forces, saying that actions like this “threatened all hopes of reform and democratic progress” and disclosing that the Salvadoran government had been asked to provide the U.S. government with the facts of the tragedy.6

The administration also pressured the Salvadoran government to put more muscle behind its apparently feeble efforts to apprehend those responsible for the murders of American citizens in El Salvador and to stop the reckless killing of civilians. On 5 April, Ricardo Sol Meza, a wealthy Salvadoran and one of the owners of the Sheraton Hotel in San Salvador, was arrested in connection with the investigation into the murders of Hammer, Pearlman, and Viera. According to Salvadoran sources, on the night before his arrest by Salvadoran police, Sol Meza had been overheard advocating a coup against Duarte.7 On 9 April the commander of the infamous Treasury Police, Colonel Francisco Morán, announced that fifty-nine members of his force had been dismissed because of their involvement in the assassination of the twenty-four slum dwellers.8 Colonel Augusto Coto, spokesman for the Defense Ministry’s Press Committee, had maintained that the victims had been killed in a firefight between guerrillas and the Treasury Police.9 Subsequent investigation revealed, however, that the victims had been blindfolded with their thumbs tied behind their backs and shot in the head. Apparently, none of the dismissed agents was prosecuted. On 15 April, FBI agents working on the Sheraton murders case arrested Hans Christ, a thirty-year-old Salvadoran and Sol Meza’s brother-in-law, in Miami. Christ was held without bail pending a hearing on a Salvadoran government request for his extradition.10

On 22 April, Under Secretary of State Walter J. Stoessel, Jr., assured Archbishop John Roach, president of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, that the four slain missionaries were not involved in politics and that the United States government would continue to press El Salvador to investigate their murders.11 In the following weeks administration sources leaked to the press that the Salvadoran government had been told to react to the evidence presented to it by the FBI or endanger United States economic and military aid.12

These moves reflected the administration’s reaction to the intense pressure exerted by critics of its Salvadoran policy. On 7 May former ambassador White told a press conference in Rochester that the administration had known for weeks that six members of the national guard had been in custody for some time for the slaying of the four American women.13 On 8 May administration sources disclosed that evidence developed by the FBI investigation and turned over to Salvadoran officials left little doubt about the identity of the assassins. The sources were skeptical that the evidence could produce a conviction in Salvadoran courts and averred that hard-line elements within the Salvadoran military had seized on the inconclusive nature of the evidence to obstruct the investigation and a possible trial.14 White’s accusation and the administration’s disclosure forced Salvadoran defense minister, Colonel García, to acknowledge that six suspects had been in custody since 29 April. Colonel García refused to provide many details, or to disclose their names and referred his questioners to the guard’s commander, Colonel Eugenio Vides Casanova. A document sent to the American embassy by the junta, and seen by some journalists, however, listed the names of three military men, including a sergeant.15

Whatever the reasons behind the timing of these disclosures, Congress remained adamant. On 11 May the Senate Foreign Relations Committee voted 11 to ι to attach conditions to present and future aid to the Salvadoran government. Under the conditions, President Reagan would have to certify every six months that the junta was making “continued progress implementing essential political and economic reforms,” that it remained committed to holding early free elections, and that it was achieving “substantial control” over all elements of its armed forces.16 Through the rest of the year all the junta could do was reiterate its commitment to constituent assembly elections. Under the circumstances, both the junta and the Reagan administration tried to remain optimistic and to present the best face possible.

By the end of the month an official release by the Department of State seemed to reflect a more balanced approach to the Salvadoran situation. The language of the release was practically a carbon copy of the Foreign Relations Committee resolution. According to the department, it was the policy of the United States “to support President Duarte’s interim government as it implements reforms, moves toward free and open elections, and works to end all forms of terrorism. . . . The U.S. provides economic and military assistance, with economic aid more than three and a half times the amount of military aid” (emphasis added).17

The allusion to Duarte’s government as interim may have been designed to soothe Western European governments that could not accept Duarte as a genuine democrat, while the reference to all forms of terrorism may have been a begrudging acceptance that rightist terrorism was a problem as well. The release was ambiguous in one important respect, however. Following a detailed description of the amounts and types of aid to El Salvador, the department concluded that “the War Powers Resolution requires the executive branch to consult with Congress before U.S. armed forces are introduced into hostilities. . . . The administration has concluded that present circumstances do not indicate an imminent involvement of U.S. personnel into hostilities” (emphasis added).18 Obviously, this left open the possibility of deeper involvement in the future.

Movement on the cases of the slain Americans was not followed by any marked improvement on the part of the junta to “substantially control” its armed forces or by a resolute effort to restore the rule of law in El Salvador. Hard-liners viewed the systematic campaign of violence and intimidation as a necessity; moderates assumed a fatalistic attitude and tried to look forward to the March 1982 constitutent assembly elections. Both were paranoid and defensive about the adverse publicity that they had brought upon themselves.

In a letter to the Maryknoll order, President Duarte claimed that the disappearance of the Reverend Roy Bourgeois, a Maryknoll priest, had been a propaganda maneuver to discredit his government. Fr. Bourgeois had disappeared in San Salvador on 26 April, and there had been fears that he had been kidnapped and assassinated by rightist terrorists. But Bourgeois had reappeared ten days later, making some confused and contradictory statements on his whereabouts.19 On 22 May the national guard claimed that it had cracked a “leftist conspiracy” to influence news coverage on El Salvador.20

The low-key approach preferred by Reagan administration officials toward matters related to human rights may have contributed to slow things down. While publicly the administration spoke of the need to act on the cases of the slain Americans, it removed one official familiar with the cases from the scene. On 27 May, U.S. consular officer Patricia Lasbury, a former Catholic nun and missionary to Peru and Brazil, was relieved of her assignment in San Salvador. Although the Department of State refused to discuss her reassignment and the embassy refused to comment, it was reported that there was apprehension about the “high visibility” that Lasbury had achieved as the embassy officer in charge of the disinterment and identification of the bodies of the four missionaries.21 An embassy source said that Consul Lasbury had worked well with her Salvadoran counterparts and, since she had been friends with some of the victims, had remained close to the investigation after the case had been taken over by the political officer of the embassy.22 Fears for Lasbury’s safety may have been more important in the decision to remove her than were any fears that she might commit an indiscretion. But whatever the case, her removal could have been taken by the hard-line element in El Salvador as an indication that the Reagan administration was not serious about pursuing the cases of the slain Americans.

Embassy officials familiar with the cases remained deeply disturbed, however. On 25 May departing chargé d’affaires Frederic L. Chapin may have breached protocol when, at a foreign ministry reception given in his honor, he stated rather bluntly that the murders “demand justice, and the world will judge the government of El Salvador and its armed forces as a result of these cases. These cases have had a profound impact on the image of El Salvador abroad.”23

Chapin’s replacement, Ambassador Deane R. Hinton, tried to sound more upbeat as he entered the scene. On 2 June, at a press conference following the presentation of his credentials to President Duarte, Hinton expressed hope that the fifty-six U.S. military advisers in El Salvador could be reduced in the near future and defended United States assistance to a reform-minded government in El Salvador as nothing to be ashamed of. To his credit, the new ambassador referred to the Salvadoran conflict as a “civil war,” becoming perhaps the first official of the Reagan administration to do so. Hinton concluded his remarks by saying that progress had been made in the case of the nuns and that he expected to receive “good news” from the junta about that case in the near future.24 But little news would be forthcoming, and the ambassador would have to revise his expectations.

Shortly after Hinton’s arrival in San Salvador diplomatic sources there believed that, if anything, the violence was getting worse, despite recognition by top officials that it was counterproductive. By that time, Colonel García and junta member Morales Ehrlich were convinced that the military’s reputation resulted from Marxist misinformation. The defense minister viewed the situation as a “black conflict”—a war without quarter—and he claimed that 180 military men were under suspension for abuses of authority and that the army was taking more prisoners—whereas few or none had been taken before, since most were executed on the spot.25

On 16 June, Ambassador Hinton admitted that the human rights situation “is bad and continues to be bad but it’s better than it was.” He pledged that he would continue to pursue human rights cases, “particularly those cases involving American citizens,” adding that he would do it quietly.26 Others could not be so quiet. In early July, Marianella García, president of the Salvadoran Commission on Human Rights, declared that the level of official repression had increased since January, that at least 11,000 persons had been killed during the first six months of 1981, and that about 30 persons were dying every day during the third quarter of the year.27 The Legal Aid Office of the Archbishop (Socorro Jurídico) believed that during the first semester of 1981, 9,250 Salvadorans had been assassinated by the armed forces and the paramilitary organizations.28

At home the administration was losing the battle over the credibility of its human rights policy. On 24 September the U.S. Senate voted 54-42 to support the Foreign Relations Committee and to condition aid to El Salvador on progress in human rights. The United Nations also had a hand in the report card. On 10 November its Human Rights Commission released a thirty-five-page report prepared by Spanish jurist José A. Pastor Ridruejo. The report concluded that although each side’s share of the violence could not be established, even approximately, enough evidence was available to conclude that there had been “a consistent pattern of gross violations” of human rights since October 1979. The report also criticized the executive and judicial branches of the Salvadoran government for adopting “a very widespread attitude of passivity and inactivity toward these violations.”29 By this time, American officials in San Salvador were referring to their weekly report of deaths as the “Grim Gram.”

On 20 August, Ambassador Hinton discussed the question of the human rights record of the government with correspondent Christopher Dickey. Asked about how much abuse of human rights the United States could tolerate, Hinton replied, “they could go bananas and go back to the policies of general whatever-his-name-was [Martínez] who handled the 1932 situation. . . . It’s utterly absurd that the United States would continue to support a government that adopted that kind of a policy.”30 Apparently, the ambassador was unaware that the death toll since October 1979 had already surpassed that of 1932. Hinton, and the administration that he represented, obviously believed that there was a vast difference between Duarte and Martínez—an assessment that was essentially correct. This was small consolation, however, to the victims of violence. In addition, although the reformist element within the government did not sanction the murders, public opinion made no distinction between moderates and hard-liners and attributed those murders to the government. Finally, the de facto policy of extermination of adversaries followed by the military was neither getting them any closer to defeating the guerrillas nor winning over the Salvadoran people to the government.

By the time of his interview with Dickey, Ambassador Hinton had become more pessimistic about the resolution of the case of the four slain missionaries, and he expressed his personal conviction that while he believed that the six guardsmen were guilty, he doubted that they would ever be convicted by a Salvadoran court.31 On 26 August, Colonel García disclosed that the six were in custody and that no formal legal action had been initiated against them.32 The defense minister failed to clarify why the men were still incarcerated if the evidence against them was so inconclusive. Perhaps there were fears about their safety or apprehension that they might implicate others—possibly their superiors—if they were brought to trial.

The case of the slain agricultural experts provides an interesting contrast. On 27 August, Judge José Albino Tinetti ordered the temporary release of Ricardo Sol Meza on the grounds of “inconsistent statements” made by Teresa de Jesús Torres López, a Sheraton Hotel waitress and the only witness for the prosecution.33 Hans Christ was freed by a U.S. court in September after Judge Tinetti recommended that the Salvadoran government drop extradition proceedings against him. Sol Meza was freed definitively on 22 October.34 U.S. diplomats familiar with the case had believed all along that Sol Meza and Christ had not fired the shots that killed the three men, but were convinced that they had assisted others who had been with them that evening in carrying out the assassination.35

There was at least one competing version. Leonel Gómez, an associate of the slain José Viera, believed that the army was responsible for the assassination and that the army targeted Viera not because of opposition to the agrarian reform project but because he and Viera had accused some army officers of corruption. According to Gómez, who had to leave the country after four assassination attempts on his own life, the FBI’S involvement in the investigation was only a sop to American critics, since there was no way that its agents could find anything.36 In either case, those responsible for the deaths of Mark Pearlman, David Hammer, and Viera apparently had no reason to fear indiscretions.

During his “unofficial trip” to the United States in September 1981, President Duarte was asked repeatedly about his government’s record on the question of human rights. On 21 September, Duarte reportedly told Vice-President George Bush that his government had dismissed six hundred national guardsmen and imprisoned sixty-four for crimes against civilians.37 On 22 September, during testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Congressman Mary Rose Oakar (D.-Ohio), a classmate of Sr. Dorothy Kazel, asked Duarte why nothing had happened in the case of the slain missionaries since April. Duarte responded that it was up to the families of the victims to press charges.38

In April, after much prodding by Senator Edward M. Kennedy (D.-Mass.), the families of the victims had been received at the Department of State by Deputy Assistant Secretary James Cheek. Following this meeting the families had been in contact with David Simcox, director of the department’s task force on El Salvador, who had advised them to retain the services of the same Salvadoran lawyer who had taken up the case of Pearlman and Hammer. The lawyer would have charged them $500 an hour and had demanded $20,000 in advance.39

Following Duarte’s testimony before the committee in September, Oakar arranged a meeting between him and the relatives of the slain missionaries. The meeting lasted two and a half hours, and although the families of the victims were impressed by Duarte’s sincerity and would contrast Duarte’s praise of the victims with the relatively cold treatment that they had received from the administration, they did not find out anything new. Duarte informed them that he had asked for more FBI assistance to crack the case, but that was all. Ambassador Hinton, also present at the meeting, had a heated exchange with Bill Ford, brother of Sr. Ita Ford, when Hinton suggested that the investigation should be limited to the six guardsmen, who, he said, had acted on their own.40 Following the meeting, Ford, who had criticized Duarte’s government for systematically murdering its own people, summarized the impression that the Salvadoran president had made on the families. Ford said, “I think it was clear to everybody that Duarte did not realize until this trip how serious this issue was in the eyes of the American people. . . . It was clear that he got no sense of that from the State Department.”41

Duarte’s hapless, if sincere, performance left Congress skeptical and his critics unmoved. Others saw him in a difficult predicament. Former ambassador White repeated his conviction that Duarte “stood for reform, for negotiation, and for an end to the savagery of the armed forces.” According to White the policies of the Reagan administration reduced Duarte’s influence to nothing, and there was little he could now do to restore the rule of law in El Salvador.42 For columnist McGrory the still unsolved murder of the nuns perfectly made the point that Duarte was “in the hands of thugs.”43 Apparently, all Duarte could do was pass the buck on to the military.

On 10 November, during his “official visit” to Washington, Defense Minister Guillermo García met with Oakar and gave her a copy of the ninety-six-page summary of the investigation, as well as some materials explaining Salvadoran law.44 On the same day back in El Salvador, Judge Mario Alberto Rivera was saying that the inquiry was at a dead end and that there was nothing more he could do in the case. President Duarte had repeated two days earlier that he had requested additional assistance from the Reagan administration to try to solve the case. A spokesman for the American embassy in San Salvador had countered that the United States was “pushing the [Duarte] government to continue the investigation.”45 The matter seemed to rest there.

To be sure, one can recite a litany of technical, cultural, and situational factors to explain the shortcomings of a judicial system that has all but broken down under the pressures of an ongoing civil war. Unembalmed bodies must be buried immediately, complicating the process of identification. There is no central agency that compiles records, making it more difficult to match descriptions of missing persons with remains found in shallow common graves or garbage dumps. It is difficult to find judges who are willing to imperil their lives by trying such cases; those who do receive little protection. The motives for some of the killings are personal rather than political; this complicates the problem of deciding which side, if either, is responsible for which killings. The state prosecutor general lacks investigative powers; those who have those powers, the military and the police, are not inclined to investigate anything.46

After all of these are taken into consideration the obvious question is Why has the Salvadoran government not taken any action to strengthen the judicial system? One possible answer is that the restoration of the rule of law has a very low priority for the government and, more specifically, for the military, which sees itself engaged in a “black conflict.” Another is that many members of the Salvadoran military cannot afford such a restoration, because they might then be held accountable for their own abuses of authority. In any case, the present state of affairs is not conducive to the establishment of democracy, since a democratic regime, much less a government that claims to be working for the inauguration of a democratic regime and must convince the population that it is serious about this purpose and capable of bringing it about, cannot neglect this responsibility.

It is possible but doubtful that the six guardsmen involved in the murders of the nuns were acting alone. Since the 1970s the Salvadoran military—and its counterpart in Guatemala—has perceived foreign missionaries and priests as guerrilla collaborators. Some of the women were returning from Nicaragua, and hard-liners may have seen this as an opportunity to obtain information that would implicate perceived adversaries and demonstrate their participation in subversive activities. Such information could then be used to silence church criticism and justify a general crackdown against religious activists. This attempt to corroborate a long-standing assumption may have turned into a multiple slaying following unsuccessful attempts to extract the information through torture—a procedure permitted under Decree No. 507, which legalizes the use of torture to obtain confessions.47

All this is speculation or, at best, a working hypothesis. The feeble actions taken in the case, however, suggest that the Salvadoran military is above the law. This may explain why by November 1981 Judge Mario Alberto Rivera had interrogated no military personnel about the murders, not even the six guardsmen.48 Yet military witnesses saw the guardsmen getting into the van with the women at the airport.49 At one point, President Duarte announced that the fingerprints of about twenty persons from the national guard and the Treasury Police were found in areas relevant to the case and in the women’s burned-out van.50 According to FBI reports the forensic evidence was inconclusive, but strong enough to narrow down the list of initial suspects from twenty to six.51 The Reagan administration believed that the identity of the killers had been established.52 Although this evidence was insufficient for conviction, it seemed promising enough to justify continuing the investigation. Yet Navy Commander Colonel Roberto Monterrosa and his four-man commission refused to continue the inquiry, and it was all but dead by November 1981.53

A key ingredient in the process of a transition to democracy is the ability of the group or coalition in favor of a democratic outcome to overcome the resistance of obstructionists. Of course the Reagan administration did not create the present Salvadoran crisis; nor did it invent violence in El Salvador. Moreover, the administration’s policies in the area of human rights are a reflection of complex ideological and political motives and do not necessarily imply that its architects condone human rights abuses. But the case of the slain Americans gave the administration an opportunity to support Duarte in a necessary and inevitable confrontation with Salvadoran obstructionists.

In May 1981 one of the journalists covering the case of the four slain missionaries wrote, “Solving the murder of the missionaries has become an important test in U.S. public opinion about whether the administration can make good its promise to push the junta toward internal reform.”54 It was apparent that by December 1981 the administration had failed that test and, perhaps more importantly, was missing a key opportunity to make a major contribution to the resolution of the Salvadoran civil war. Instead, the administration remained at a loss as to how to cope with a “cycle of violence and counter-violence that could only be broken when a democratic solution thwarts those who seek a solution by killing.”55

Democratic solutions, after all, do not come without effort. They must be forged. In El Salvador, a country faced with the prospect of a long civil war, saddled with a deteriorating economy, and governed in part by a moderate faction desperate for support on key issues, the prosecution of those responsible for these murders would mark an important change of direction. Instead, the moderate aperturistas in the government could only look to a forthcoming election for some kind of respite, while its nominal allies, the military, seemed bent on producing a military victory and continued to overlook the question of the restoration of rights. At a time when the reforms had slowed to a trickle, when the Right had returned to the offensive, and when the moderates could have used all the help they could have gotten, the administration continued to view the guerrillas as the main threat and to use geopolitical criteria to evaluate its policy options. Meanwhile, the military continued its campaign to crush the very groups whose support would be crucial to the resolution of the conflict through a political settlement that included open elections.

But columnist McGrory’s timing was off. The perfect proof that the hands of the moderate civilians were tied had come before, when Attorney General Mario Zamora was able to do little to clarify the situation of the disappeared in late 1979, when Zamora was murdered in February 1980, when Archbishop Romero was killed in March of 1980, and when nothing, absolutely nothing, had happened to those responsible for these murders. Duarte’s inability to deal with political murders meant that he was not any closer to thwarting the obstructionists in December 1981 than he had been when he assumed office in December 1980. The Reagan administration’s inability or unwillingness to help Duarte find the opportunity as well as the means to cope with this problem implied that it was not any closer to understanding the Salvadoran crisis in December 1981 than the Carter administration had been in December 1980, or in October 1979.

The man perceived to be in the hands of thugs and the administration that kept him in power had made little progress in a key area of the Salvadoran process of transition. Despite their protestations to the contrary, neither seemed willing or able to restrain the Salvadoran armed forces. To make matters worse, the Reagan administration’s preoccupation with the military aspect of the crisis and its ramifications for U.S. security made the Salvadoran military confident that it was indispensable to the ending of a civil war which they had helped start.

A Salvadoran Horror Story

The sensational details of the killings of the six North Americans may distract attention from two important facts. The first is that the overwhelming majority of the victims of the political violence have been Salvadoran citizens. The second is that most of them have been killed by the armed forces.

Regardless of which set of figures one chooses, the official figures used by American embassy staff to compile their weekly death toll report or those released on monthly and quarterly bases by the Legal Aid Office of the Archbishop (Socorro Jurídico), one can see that the human cost of the Salvadoran civil war has been mounting rapidly. Table 7-1 offers an abridged summary of the periodic data provided by Socorro Jurídico, with some indication of the largest categories of persons affected by government violence. The breakdowns presented in the table show that the principal targets of government violence are those sectors of the population suspected of sympathizing or collaborating with the guerrillas: students, teachers, clerical workers, and residents of rural areas where the fighting was concentrated during 1980-81. In addition, it seems safe to assume that many of those listed as of “unknown” occupation are part of the vast army of unemployed and underemployed which was already large in the 1970s but has now swollen considerably as a consequence of the civil war and its attendant economic crisis.

The data presented in Table 7-1 suggest that although murders committed in urban areas have attracted more attention, a large proportion of the victims have been country dwellers. After all, El Salvador is still a predominantly rural society, and the level of violence has been higher in the countryside.

Table 7-1 does not include figures on killings attributed to the guerrillas, who obviously have done some of the killing.56 Archbishop Arturo Rivera y Damas chided the staff of the Socorro Jurídico, his own agency, for not including victims of leftist violence in their release “The Statistical Balance of the Repression.” The archbishop and most knowledgeable observers, however, support the accuracy of the figures published in the report.

In a war with few prisoners each side’s ability to inflict casualties on the other depends not so much on weaponry but on the frequency of engagements with the enemy, the size of the territory under one’s control, and each side’s definition of “enemy” itself. The guerrillas confront the army only sporadically, they control small chunks of isolated areas, and they are relatively few; yet the number of casualties in the countryside remains high. One reason for this is that guerrilla columns have become more numerous and widespread in the last year. A more important reason, however, is that the army pursues anything resembling a guerrilla, and government forces and paramilitary elements treat guerrilla sympathizers as combatants. By contrast, the guerrillas attack anyone in uniform, government officials, trade union leaders, members of ORDEN—which, although “illegal,” continues to operate freely—the wealthy, and the prominent.57

Although estimates are hard to come by and somewhat unreliable, most impartial observers agree that in those cases in which it is possible to impute responsibility, 80 to 90 percent of the victims were killed by the armed forces or paramilitary groups. In late 1981, Colonel Garcia estimated that 30,000 had been killed since the October coup, 24,700 of whom—according to Garcia—had nothing to do with the conflict.

Before the Salvadoran civil war erupted in full, every small town and village in El Salvador had been activated politically, especially in the departments of Chalatenango, Morazán, and Cabanas. This was a tense situation in which the local comandantes or the jefes civiles remained close to the landowning element, the national guard garrison, and the paramilitary groups. Christian Democrats and their allies remained in contact with their leaders in San Salvador, reporting to Duarte and Morales Ehrlich if trouble erupted. Opposition elements remained visible, supported by the local chapters of the popular organizations which, in some instances, could depend on the guerrillas operating in the area to retaliate against any attack. The tension was compounded by competition between different unions trying to enlist peasants and agricultural workers. A precarious equilibrium reigned in which murders and violence were limited because the conflict, although intense, was not polarized between just two sides and no one group could dominate the rest. This schema is fairly representative of circumstances in the countryside in early 1980, but it did not last long. After the enactment of the agrarian reform statutes, in March 1980, the situation deteriorated rapidly.

One target of violence orchestrated by factions included in the government was precisely those who were to benefit from the reform. Members of the national guard, who had always received a salary supplement from local landowners and who naturally sided with them in any dispute, began to sabotage the reforms. In a series of actions so similar as to suggest a pattern, national guard elements appeared in the cooperatives organized in the largest farms, which were included in Phase I of the Agrarian Reform, and assassinated leaders of the cooperatives, as well as any ISTA officials found on the premises.

The role played by the UCS in this conflict is illustrative of the kind of complexity that one finds in the present Salvadoran situation, a complexity that can in no way be used to hide the shortcomings of the Duarte government or to suggest that the situation is beyond comprehension and rectification. The UCS had been created under the auspices of the AIFLD, an organization supported by the AFL-CIO and distrusted by many labor federations in Latin America for its anti-Communist biases and its tame trade unionism, which did not challenge the oppressor.58 The UCS had always been viewed as too close to the government and too cooperative with the oligarchy in El Salvador. By the time of the enactment of the agrarian statutes in 1980, however, the UCS was a more militant union, and the Christian Democrats and the military moderates like Colonel Majano wanted to use it to create political support in the countryside. The military had been able to mobilize the peasantry before, as during the abortive reforms of 1976, but the PDC had always been relatively weak in the countryside, USC leaders like José Rodolfo Viera, who at the time of his assassination had become president of the ISTA, wanted to take advantage of this new opportunity to redress long-standing grievances.

The UCS, the ISTA, and anyone associated with them became targets of rightist violence. On 5 June 1980 representatives of eight UCS departmental executive councils protested to the government demanding an end to the violence and better protection for their affiliates.59 By November 1980, Viera could charge that 80 percent of the murders in the countryside could be attributed to the Right and that violence against the cooperatives was increasing. For Viera the level of violence in any given area was directly related to the attitudes of local military commanders toward the reforms and whether or not farms supposed to be included in Phase I had been turned into cooperatives. At the time he was murdered, Viera was pressing for implementation of Phase 2 of the Agrarian Reform, which would have affected the medium-sized farms.60 Viera believed that implementation of Phase 2 would bring three other peasant unions over to the government’s side, thereby widening its base of popular support.

Violence against the cooperatives did not abate during 1981, however, even though Alejandro Duarte, the president’s son and himself the target of several assassination attempts, was in charge of a task force monitoring the situation and reporting directly to his father. On 25 February 1981, during testimony before the Foreign Operations Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee, AIFLD executive director William C. Doherty, Jr., claimed that, according to ISTA reports, 133 of the 184 assassinations perpetrated against land reform beneficiaries and ISTA officials could be attributed to the security forces or to elements associated with them.61

Written testimony submitted by the United States section of Amnesty International to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee painted a broader picture. “Amnesty International has asserted that a campaign of murder and abduction has been launched against peasants in El Salvador. The announcement of the agrarian reform program was coupled with the arrival of troops [operating in open coordination with the paramilitary group ORDEN], ostensibly to carry out agrarian reform programs. These operations have resulted in the abduction and murder of hundreds of men, women, and children, the razing of villages and the destruction of crops in the Departments of Suchitoto, Morazán, Cuscatlán, and Chalatenango.”62

By early August 1981 Salvadoran government officials were labeling the reform program a political success, but it was only a modest one, since only 386,010 persons had benefited from the program, which had left 85 percent of the coffee, 75 percent of the cotton, and 60 percent of the sugarcane grown in El Salvador in relatively few, private hands.63 Deeds and, more important, credit had been slow in coming to the cooperatives,64 and the Reagan administration had come out squarely against the implementation of any aspect of Phase 2.65 In early August, during a ceremony conferring deeds to a series of beneficiaries, Agriculture minister and junta member José Antonio Morales Ehrlich vowed that “the process will never retreat.”66 The limited political success afforded by the reforms had come at a very high price, however.

If peasants with relatively good connections with the moderates in the government paid a high price for the limited benefits afforded to them, members of other peasant organizations felt the full rage of the Right. Identified from the outset as “subversives,” sympathizers and members of the UTC, FECCAS, and similar peasant organizations had to run for their lives once the state of siege was declared. Many towns were deserted, as the population of some villages simply disappeared into the countryside.

In mid-1980, journalist Richard Alan White visited the Arcatao Valley in Chalatenango. He found that all but about a dozen of the four hundred families residing in the town of Arcatao had fled; trying to locate the guerrillas, estimated by the local national guard commander at about one thousand, White and his companions found a few adolescents with small arms and shotguns and hundreds of malnourished and ill peasants—a few heads of household, old people, and, mostly, women and children. The majority had left the town months before to escape from the national guard and ORDEN They lived under the constant threat of attack by the Salvadoran army and, as they were close to the border with Honduras, under constant harassment by the Honduran army. Their only protection came from guerrillas—some of whom were probably their missing male relatives—who dominated the Arcatao Valley. White found a similar situation in the Torola Valley, in Morazán, where government forces had retreated into the town of Perquín.67

New York Times correspondent Raymond Bonner found similar conditions in the department of Suchitoto, which he visited in July 1981. Bonner observed army units moving refugees out of the camp of La Bermuda into the town of Suchitoto, where the popular organizations had been strong in previous years. The department itself was one of those in which the guerrillas of the FMLN were strong, and much of the countryside was a no-man’s-land. Some of the refugees being moved reported instances of army units coming into their camp in April and May and leading people away to be shot.68 In a follow-up story, Bonner reported that the two thousand or so refugees in La Bermuda had been scattered around several locations, including an old penitentiary at Suchitoto, with little regard for keeping families together.69 In a foray into the countryside, Bonner found poorly armed peasant guerrillas, who claimed to be in control of the area.70

Whether the manner in which the Salvadoran armed forces were pursuing the guerrillas resembled methods employed, unsuccessfully, by the United States in Vietnam is a question that can be argued. But it is clear that the army’s first priority was to deny potential resources to the guerrillas, including seeds, animals, crops, and likely recruits, and that it paid little if any attention to winning the support of the peasantry. To make matters worse, some Department of State officials insisted on accusing some of the relief organizations, primarily Oxfam, CEDEN (Evangelical Committee of National Defense), and Caritas, of helping the guerrillas. This had the obvious impact of making the military even more careless and cruel in its treatment of the refugees. Oxfam representative Lawrence Simon complained that accusations like these had the effect of signing someone’s death warrant in El Salvador.71

Perhaps those in the camps were lucky, if one compares them to the hundreds of thousands who were drifting inside El Salvador. In August 1981 the regional office of the U.N. High Commission on Refugees reported that about 300,000 Salvadorans, almost the same number as that which the government claimed had received benefits under its program of agrarian reform, had fled the country, while an additional 180,000 had been uprooted from their homes but were still in the country.72 Of this total, some 140,000 had registered with the government, but about 42,000 had not, perhaps for fear of the government itself.73 According to a U.S. AID official with the American embassy in San Salvador, the highest concentration of refugees was in the departments of Chalatenango, Morazán, and Cabanas,74 precisely the areas where the popular organizations had been strong, where the guerrillas were more active, controlling a corridor along the border with Honduras, and where the army viewed most refugees with extreme suspicion.

These were also the areas where the army and the guerrillas fought pitched battles for control of strategically situated towns and armed forces sweeps through the countryside resulted in a high number of peasant casualties. During 1981 the towns of Arcatao (in January and June), Perquín (in August and November), El Rosario (April), San Francisco Gotera (January), and San Agustín (October) were occupied by guerrillas, who dug in and stood their ground against the army for several days. The army was forced to commit between 1,500 and 3,000 troops to retake each of these towns. Since, in many cases, government troops are conscripts in their teens, who have only minimal training and who shoot at anything that moves, innocent civilians were shot by accident. Others were killed in aerial attacks and by artillery fire.

Army sweeps along the border with Honduras became possible after the normalization of relations with Honduras on 10 December 1980. Several instances of Salvadoran troops crossing into Honduras have been reported, including one operation against the village of Los Filos in which the army airlifted units into Honduras.75 These sweeps, including a major one in October 1981 in the area around San Agustín on the Lempa River, are conducted by units trained by U.S. advisers, including the elite Atlacatl Brigade, which are supposed to be more “professional.”76 Reports from peasants, however, claimed that the brigade was using search-and-destroy and scorched-earth tactics.77 According to Robert S. Leiken, a fellow and director of the Soviet-Latin America project at the Georgetown Center for Strategic and International Studies, military atrocities continued during operations in the countryside. Leiken believed that, if anything, the behavior of army units had gotten worse; decapitations and mutilations had become more frequent. Leiken’s testimony was congruent with the view expressed by diplomatic sources in San Salvador that the brutality and incompetence of the army were alienating the civilian population.78

Whatever excuses may be offered for the army’s treatment of civilians in battle zones, no reason can be offered for the well-documented instances of cold-blooded murders of refugees.79 The Reagan administration failed publicly to condemn these atrocities and belittled reports of continued killings of civilians. Yet, conclusive proof that these reports were no exaggeration, nor the result of Marxist misinformation, came on 16 November 1981 when a group of international observers visiting the La Virtud refugee camp inside Honduras witnessed and were able to prevent an attempt by Salvadoran troops and ORDEN elements to execute a number of refugees whom they were leading away from the camp.80

The analogy with Vietnam and the ultimate wisdom of counterinsurgency are still impassioned themes for Americans. One American fantasy embodies the determination to stand up to what some perceive as Communist aggression. Another doubts whether the United States can or indeed should play any constructive role in the Third World. In either case, it is unjust to sacrifice the Salvadorans—either to another reactionary dictatorship or to a revolutionary government controlled by one hegemonic faction—to prove a point about American foreign policy. Those who claim that these are the only realistic choices for the Salvadorans are making two different versions of the same racist, patronizing, and imperialist argument, even if they seek to justify actions as different as military escalation or complete withdrawal by the United States.

Not all Third World conflicts are alike, and they should not be forced into the mold of one, and only one, specific instance—in this case, Vietnam. Of course for United States citizens the Vietnam experience is the best reference point. In El Salvador, however, it would take considerably less effort from the United States to produce a catastrophic outcome. There failures of omission can be as important as failures of commission. The United States has done much to complicate things by failing to help carry out more resolute action against obstructionist actors on the Right and by failing to insist on the need to give top priority to a restoration of the rule of law.

A resolution of the Salvadoran conflict, however, ultimately depends not on United States actions but on the actions of the Salvadorans themselves. This is an inference from recent history, which demonstrates that even superpowers lack the ability to control major historical processes for long periods of time, short of extreme measures such as genocide, which, needless to say, the American public will not tolerate. Congressional opposition is another structural constraint that would prevent a major escalation, while the guerrillas have shown that they can survive even a fairly efficient use of the resources available to the Salvadoran military by late 1981. Yet complete withdrawal by the United States would not necessarily result in a victory for the Left, since the Salvadoran oligarchy and its rightist associates have shown that they are capable of mounting a determined and ruthless onslaught against democratization, and they can summon large numbers of people to their cause, including those landowners not yet affected by Phase 2.

Yet counterinsurgency and repressive reformism as a solution for El Salvador must be questioned. What is the sum of reform plus genocide? What determined whether, by December of 1981, a family of Salvadoran peasants had been incorporated into one of the new agricultural cooperatives or dismembered, disemboweled, and scattered over the landscape? Was this really the solution to one hundred years of oligarchic exploitation? Under what kind of criteria could anyone believe that a great deal had been accomplished? Was this not a perverse continuation of the schizophrenic language of Salvadoran politics? Did this mean that anyone whom the cooperatives could not accommodate or whom the strategic hamlets could not shelter was to be considered the enemy?

What the Carter administration would have done in this situation will remain a matter of speculation, but, without a doubt, this process began to unfold during the Carter period. What is not pure speculation is that the Reagan administration did not help the situation by insisting that the military aspect of the crisis be given more attention and that the government abandon Phase 2 and try to reconcile itself with the private sector. This only made the government more suspect, even in the eyes of those who had benefited from the reform, and tended to confirm the suspicions of the opposition. In March 1981, former ambassador White predicted that the only way the Left could gain strength in El Salvador was for the government to move substantially to the Right.81 This is precisely what the Reagan administration wanted to accomplish.

The Private Sector and the Salvadoran Transition

Seldom has a United States diplomatic mission made strenuous efforts to bring together two actors as dissimilar as the Christian Democrats and the organizations of the Salvadoran private sector. The irony is that if similar efforts had been made to bring together the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats and the Communists in the FDR, the Salvadoran process of transition would have turned out quite differently. Instead the United States sought to ridicule, discredit, and minimize the significance of the FDR.82

The behavior of the leaders of private sector organizations suggested that there was really only one political faction within the Salvadoran private sector. The different organizations representing sectoral interests of the Salvadoran bourgeoisie certainly behaved as one when political questions were raised. One element which may have contributed to their cohesiveness during this period of time was that they shared an unmitigated, undiluted hatred of José Napoleón Duarte. Small wonder that efforts to bring the PDC and the private sector together produced, in their most successful instance, a shotgun wedding and, in most other cases, open warfare. The former came during the abortive general strike of August 1980, in which representatives of the private sector, the military, and the PDC came together to coordinate a common strategy to defeat the FDR strike.

Since Mario Antonio Andino resigned from the first junta, and since a number of conservative figures associated with private sector interests were not reinstated in their positions following the massive exodus of senior officials in December 1979, the Salvadoran bourgeoisie had been chafing under what it considered a “lack of representation” in the government. The Christian Democrats’ reply was that the presence of the private sector within the first government formed after the October 1979 coup was divisive and allowed the bourgeoisie to sabotage the program of reforms from within. Since the bourgeoisie’s attitude toward such reforms—it considered them demagogic, unrealistic, and communistic—remained unaltered, reform-minded government officials preferred to keep it at arm’s length, where it could not so easily undermine plans for reform.

These private sector organizations representing the bourgeoisie were not those of the lunatic fringe that dared publicly to throw their support behind Roberto D’Aubuisson, as did the FAN and the FARO. Nor were they dominated by the oligarchic element that financed death squads from Miami or Guatemala City. Instead, these organizations represented the interests of the business community of El Salvador, which, although not actively linked to the disloyal Right, refused to come to terms with the new reality after October 1979. Despite their protestations of support for progress, their attitude became more intransigent. They demanded that the government change its economic policies, accused the government of plunging the country into economic chaos, and then demanded that the Christian Democrats abandon the government altogether. What they hoped to accomplish all along was to persuade the military to get rid of the Christian Democrats and to roll back the “unrealistic reforms.” Instead of forming a coalition with the Christian Democrats they harbored the not-so-secret hope of taking their place in a new coalition with the military. The emergence of such a coalition could restore a system of reactionary despotism to El Salvador.

The Alianza Productiva (AP) emerged during the turbulent month of May 1980. The AP included the ANEP, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Salvadoran Industrialists’ Association (ASI), the National Federation of Small Enterprises (FENAPES), the Society of Salvadoran Merchants and Industrialists, the Federation of Professional Associations (FEPRO), the Union of Salvadoran Entrepreneurial Leaders (UDES), and the Coordinating Council for Agricultural and Livestock Enterprises (CCEA). The emergence of the AP could have meant a rejuvenation of the ANEP and could have marked an important shift in the role and political attitudes of Salvadoran private enterprise. But this was not to be the case.

In November 1980 an AP delegation went to Washington to confer with members of the Reagan transition team in order to test the waters and gauge the kind of support that the new administration would give to the Christian Democrats.83 By March 1981, once it was apparent that Duarte had survived the Reagan transition and would remain in power for some time, the AP had begun to criticize the economic policies of the government. On that occasion the AP opposed retroactive increases in export taxes and expressed concern about the disappearance of credit sources and business failures.84 The AP maintained the old intransigence of the oligarchy toward labor. For example, the ASI greeted some of the labor reforms introduced by the government in May 1981 with the criticism that they would generate conflicts at the wrong time.85 In early May former ANEP official and new Salvadoran ambassador to the United States Ernesto Rivas went further, telling a press luncheon at IMF headquarters in Washington that the elections should be postponed.86

To be sure, the economic situation was extremely difficult. The year 1980 saw a decline in the GDP of 9.5 percent, mainly because of disinvestment. Agricultural production went down by 7 percent, while construction and trade decreased by 17.5 percent and 12.1 percent, respectively. A total of 113 companies closed down.87 This bleak picture was not solely owing to government incompetence; nor was it—by May 1981—only a result of the civil war. Coffee had been hit by bad weather and soft export prices; cotton had become a victim of the international credit squeeze, not the guerrillas. The 1980-81 production of 199,226 bales was harvested on the lowest acreage planted in twenty years. Sugar growers had to put up with some sabotage, but they increased production from 3.4 million quintals for 1979-80 to 3.9 million quintals in 1980-81. Their main source of irritation was that INAZUCAR, the state marketing company, would not grant credit without collateral and that it demanded the right, once a loan had been granted, to step in and appropriate the harvest if it judged that mismanagement threatened its investment.88

The government was trying to get international credit as best it could. The United States promised $126.5 million in economic aid for calendar year 1981, including $44.9 million earmarked for the private sector.89 Other sources of credit, however, were hesitant because of the human rights record of the government. West Germany, Denmark, Canada, and Mexico had blocked IDB credit to El Salvador in 1980 and were questioning the government’s request for the initial $120 million installment of a three-year package of $360 million.90 By September 1981 the IMF had not made a decision on this request, which had been pending since October 1980.91

The military remained relatively quiet during most of these wars of words between the PDCand the AP organizations. One consequence of the reforms had been to increase the fiscal base of the state, as well as to make it less dependent on the private sector. This suited the military fine, since it evened the score for the humiliation it had received from the failure of the ISTA in 1976. On the other hand, it remained relatively unenthusiastic about Phase 2 of the Agrarian Reform and about any measure that could be viewed as an attempt to pacify labor. In June, when Economy and Foreign Trade Minister Guillermo Salazar Díaz, a political independent, made the suggestion that the wage freeze could be lifted soon, military leaders took exception. Defense Minister Guillermo García expressed the opinion that “people cannot be offered something they won’t get,” while Commander in Chief Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez called the Diaz proposal “a grave threat to the nation.”92 The minister left the country immediately.

Perhaps encouraged by this turn of events, the AP increased the level and frequency of its criticisms. The ASI seconded the pronouncements made by Manuel Enrique Hinds, former minister of economics under the first junta, suggesting that the Duarte government was based on “participatory democracy, which at bottom is a socialistic, coercive, and collectivist system.”93 This contrasted with a statement made in March by outgoing ASI president Eduardo Menéndez that the ASI stood for representative democracy and individual freedom and for the diffusion of private capital through productive labor.94 Hinds, for his part, told a gathering of six hundred cheering Salvadoran businessmen that they were faced with two choices: communitarianism or communism. Behind communitarianism, he continued, there was “a steely dictatorship only comparable to Marxist tyranny.”95 Before his return to San Salvador for this engagement and for other activities on behalf of the AP Hinds had disclosed in Washington, D.C., his new place of residence, that the private sector had declared war on the Duarte government and that it would not cease until it fell. Opposition to economic policy had turned into a political campaign against the very existence of the government.

The methods and the language utilized by the AP did not differ very much in style and substance from those utilized by the ANEP and the FARO in 1976 against the ISTA. This suggests that even though some of the businessmen who had stayed in El Salvador no longer viewed the oligarchic group outside the country as their natural leaders—as one businessman told New York Times correspondent Warren Hoge, “Those people in Miami must realize that they can’t return as people with any position in society”96—they themselves did not know any better. In other words, they were as consevative and as opposed to the reform of Salvadoran capitalism as was the more recalcitrant element of the traditional oligarchy, who had, for the most part, left the country. On the other hand, by July 1981 knowledgeable observers in San Salvador were remarking on the high number of millionaires who had returned to the country recently, encouraged because they believed that the Reagan administration was pushing the Duarte government toward a more conservative position.97

The ANEP’S executive director, Juan Sandoval, was more explicit in his own contribution to the ongoing campaign, stating that the private sector did not support what the Christian Democrats were doing in El Salvador.98 The CCEA also joined in the chorus, issuing a declaration which blamed “the so-called structural reforms” and “the struggle for power on the left between the PDC and the FDR” for the chaotic economic situation of the country.99 On the day of the CCEA declaration, 30 June, the Independent Cotton Growers Front urged repeal “of the so-called land to the tiller law,” demanding that all cotton lands be exempt from the act and arguing that many growers were not planting any cotton for fear that they would lose the land before harvest.100

On 1 July relatively few people were surprised when President Duarte accused the private sector of being his principal enemy. With language reminiscent of that used by Colonel Majano the previous December, Duarte said, “The private sector is in its final offensive to overthrow the government. The politicians of the private sector . . . want to take away all the economic reforms.”101 Duarte announced that titles would continue to be awarded in accordance with the law, but he extended the wage freeze and the accompanying freeze on certain staples, professional fees and health care services, school tuition, and rents.102 Apparently, Duarte decided to abandon all plans for the implementation of Phase 2. This, together with the treatment received by departed minister Salazar Diaz and Duarte’s failure to come out in Salazar’s defense, was said to have angered Agriculture Minister Morales Ehrlich, who had put his personal prestige and more on the line to see the reforms through, and Foreign Minister Chavez Mena, a man respected in progressive Salvadoran circles, to the point of resigning.103

Watching this sequence of events, former ambassador Robert White scolded the Reagan administration once again for undercutting Duarte and for contributing to a slow-motion coup unfolding in El Salvador.104 A 16 July speech by Thomas O. Enders, assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs, had been awaited with anticipation by Salvadoran observers, who were anxious to see which way the wind was really blowing from the Reagan administration. Enders’s speech gave priority to a political solution, which he believed would have three essential components: “The first . . . is that promises must be kept. . . . Second, there must be demonstrable progress in controlling . . . violence from all sources. . . . Third, . . . all parties that renounce violence should be encouraged to participate in the design of new political institutions.”105

Enders’s speech, announced in advance as a clarification of administration policy in El Salvador, seemed to have messages for everyone, including, of course, rightist Salvadorans. Although it certainly projected the biases of the Reagan administration, the speech was so balanced that practically everyone except the guerrillas could find a positive signal in it. Perhaps the weakest point of the speech was the contradiction produced by couching the conviction that “only Salvadorans could resolve their divisions” within the caveat that “a political solution would not succeed unless the United States sustained its assistance to El Salvador.”106

Never one to leave matters of interpretation to others, the Salvadoran bourgeoisie returned to the offensive. On 19 July, AP representative Juan Vicente Maldonado stated his view that the speech was proof that “the United States was no longer giving unconditional support to Duarte,” adding that it appeared that the United States would not continue to aid Duarte unless he adopted a more conservative economic policy and incorporated a businessman in the junta. Maldonado claimed that the AP wanted to play a positive role in developing a free-market economy along the lines of the Milton Friedman model.107

Maldonado did not bother to explain how Dr. Friedman’s model could coexist with a government that called itself “revolutionary” and was trying to change the undesirable features of the capitalist system of El Salvador. He may have been aware that Ambassador Hinton was not unsympathetic to the idea of closer collaboration between the PDC and the AP. Of course Hinton was continuing an effort that had been going on for some time. How a stable and centrist coalition could result from Christian Democratic communitarianism and laissez-faire economics was yet to be determined. Maldonado and his associates, however, were primarily interested in getting someone from the AP into the junta.

Also on 19 July, Conrado López Abreu, president of the Salvadoran Chamber of Commerce, repeated a charge frequently made by the Salvadoran Left, namely, that the Duarte government stayed in power only because of the support of the United States. López added that he and other representatives of the AΡ had discussed their drive to join the government with Hinton and that the ambassador had not rejected what they were trying to do.108 Hinton acknowledged his role in the “big, delicate negotiations” that were going on, but he “refused to negotiate in the press.”109 Although Duarte denied that any negotiations were taking place, an unidentified cabinet minister admitted that the government was talking to businessmen, but not to those sharing the conservative views of Maldonado and López.110

On 22 July, Duarte accused business of trying to destabilize his government and of actively working to persuade the armed forces to oust him for his alleged contribution to the economic chaos of the nation. “I want to stress,” Duarte said, “that extreme rightist groups have infiltrated some groups and are bent on destabilizing the government.”111

The expected changes in the junta did not take place. René Fortín Magaña, a member of the 1960 junta and former dean of the law school of the National University, did not join the junta as it had been rumored he would.112 The government had hoped to incorporate FEN APES president Luis Mendoza, but apparently decided that there was no need to do so; or perhaps Mendoza did not want to take his organization out on a limb. Magaña’s group, formed primarily by conservative professionals and businessmen, became a political party, the Acción Democrática (AD), shortly thereafter. Magaña denied that the AD was merely a front for landowners.

On 31 July, Ambassador Hinton was still trying to salvage the situation. During a speech to a lunch gathering of the American Chamber of Commerce of El Salvador, he urged the PDC and the AP to come together, since neither the Christian Democrats nor the private sector would survive a Marxist takeover. Hinton also used the opportunity to praise Duarte’s record, defended the government’s austere monetary and fiscal policies, and argued that the main problem with the economy was the shortfall in export earnings owing to soft demand in the world markets.113

The AP remained undaunted, denouncing government policies during a three-day symposium. It attacked policies that had affected the oligarchy, such as the nationalization of banks and the freeze on land titles, asked for a complete repeal of Phase 2 (still in the statute books), and demanded a revamp of coffee export taxes. On a more general level the symposium requested: (1) a one-year moratorium on debts, (2) more long-term loans at lower rates of interest, (3) cuts in public sector credit, (4) a program to channel loans directly to business, (5) suspension of prepayment for letters of credit, and (6) rapid payment of the 650 million colones (about $260 million) owed to agriculturalists affected by agrarian reform.114

In summary, the differences between the AP—which favored the rollback of all reforms and demanded immediate relief from the burdens imposed by a world economy in recession—and the communitarianism of the PDC could not be reconciled with ease. The ANEP wanted Duarte to adopt more conservative economic policies, but protested fiscal and monetary stringency. The AP wanted to make a “positive contribution” but with the theories of Milton Friedman. More than anything else, however, they wanted Duarte out.

It was probably during August that Duarte realized that he needed to have a talk with his supporters in Washington in order to explain his views and prevent any further erosion of his influence and the disintegration of his government. On 15 September, at a rally that drew a large and relatively enthusiastic crowd to the Flor Blanca Stadium in San Salvador, Duarte asked the Left to lay down its weapons and participate in the elections.115 He was satisfied with the turnout, which he saw as an expression of support for his government, but others, accustomed to heaping praise on the military, saw things differently. Editorials in El Diario de Hoy stated:

Our people wanted to make explicit . . . its profound appreciation for the heroism of the soldier and of all of those who, weapons in hand, reject aggression. . . . Until two years ago, our country allowed, no doubt to comply with the program of “human rights” imposed by Carterism, bands of hoodlums to dedicate themselves to sowing disorder and imposing terror on the citizens. . . . Our people has given a vote of confidence and support to its armed forces, recognizing that the military response is the only one that can return peace to all and the appropriate climate to rebuild the nation.116

Shortly after President Duarte left for a visit to the United States, a familiar character returned to the scene. During the weekend of 19 September, Major Roberto D’Aubuisson visited newspapers in San Salvador to announce the formation of a new political party, the National Republican Alliance (ARENA).117 On 28 September, as hundreds of police and soldiers watched impassively, he announced to a press conference in San Salvador that he planned to enter the elections.118 It was unclear why so many elements of the army and the police were present, but, a few weeks later, during his official visit to Washington, Defense Minister Garcia explained to editors and reporters of the Washington Post that D’Aubuisson had reentered the country under a preelection amnesty and that there were no warrants for his arrest outstanding.119 It all had a familiar ring.

Taking a cue from the low-key reception given Duarte in Washington, the AP continued its tough talk. On 8 October a spokesman for the Alianza accused Duarte of preparing to open direct talks with the Left and called Duarte a “little Caesar” intent on taking El Salvador toward totalitarianism.120 This was a challenge not only to the Christian Democrats but also to Commander in Chief Gutiérrez and Armed Forces Chief of Staff Colonel Rafael Flores Lima, who had expressed approval of leftist participation in the elections and had shown interest in opening up a political dialogue with the Left.121

During October the Salvadoran Right changed its stance and began to talk about participating in the constituent assembly elections, but only if all the Christian Democrats were removed from the Central Electoral Council (CCE). Four rightist parties made this demand, including the always pliable PCN, the minuscule Partido Popular Salvadoreño (PPS), which missed its chance to play a constructive role in a previous political era in El Salvador,122 Fortín Magaña’s AD, which was wooing practically the same kinds of persons who had earlier supported the PPS, and D’Aubuisson’s ARENA. Chele Medrano’s Partido de Orientación Popular (POP), representing primarily those agricultural sectors not yet affected by agrarian reform, was the only one that did not insist on this precondition for its participation.123

On 31 October the government legitimated what had been taking place for weeks by lifting the ban on political parties, whose activities had been forbidden since the imposition of the state of siege in March 1980.124 On 5 November, during a meeting of the Political Forum, a conference including all six legal parties contesting the election, the Christian Democratic members of the CCE were ousted by a 4-2 vote.125 Not content with this victory, spokesmen for the rightist parties said later that they would move to restructure the regime; to demand the replacement of the ministers of labor, education, and the interior and of the president of the ISTA; and to ask for the resignation of all mayors and departmental governors, many of whom were Christian Democrats.126 The Christian Democrats reacted to these demands by calling the initiative a “paper coup.”127

The Christian Democrats tried to put the best face on events. They hoped that the continued support of some key military figures, plus the Reagan administration’s inability to move them much further to the right, would see them through the constituent assembly elections, set for 28 March 1982. Although the PDC leadership did not expect these elections to give it the ability to control the army—indeed, it could not realistically expect to capture the majority of the sixty seats up for grabs—it did hope to use the elections to build for the future “within the realm of the possible.”128

Meanwhile, instead of warning the Salvadoran Right to behave itself— which he had failed to do a single time since coming to office—Secretary of State Haig continued to denounce Cuban interventionism, to ask the Pentagon to prepare contingency plans for any eventuality, and to threaten Nicaragua.129 However, the other important foreign ally of the Christian Democrats—and perhaps the only true ally they had left—took exception to this and made a different pitch. On 19 November 1981, Venezuelan President Luis Herrera Campins, himself a Christian Democrat, told reporters in Washington that he had expressed his concern to the White House about the United States’s neglect of the threat from the right in El Salvador.130 Duarte received another boost on 8 December when the Organization of American States voted 22-3 to endorse a resolution approving of the Salvadoran elections.131

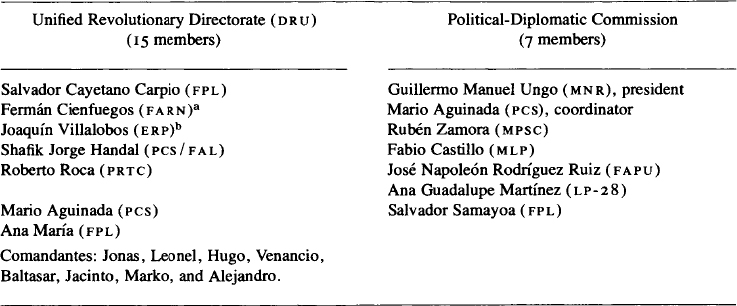

Trying to assuage his conservative critics, Duarte adopted some of the views of Secretary Haig and borrowed a page or two from the secretary’s repertoire of tough anti-Communist rhetoric. In early October, Duarte recalled Salvadoran Chargé d’Affaires Joaquín Maza Martelli from Managua. On 9 October, in a speech to the American Chamber of Commerce of El Salvador, Duarte rejected a Nicaraguan offer of mediation.132 A month later he sent a letter to the editor of the Miami Herald denouncing a “campaign of misinformation being orchestrated by Cuba and the Soviet Union to destabilize his government” and praised the Salvadoran armed forces for the “heroic battle” that they were waging.133